The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy — Introduction — Crime Library

On this most Americans can agree: President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963.

But four decades later, just about every other detail of the assassination of the charismatic, photogenic politician is subject to debate.

Was the CIA behind the murder? Fidel Castro? The Mafia? The FBI? LBJ? The Russians? Martians?

Or were Lee Oswald, the accused assassin, and Jack Ruby, Oswalds killer, simply two lone nuts who managed to carry out a pair of inconceivable shootings?

For most Americans, its a kind of a parlor game, says Professor John McAdams, who teaches a course on the assassination at Marquette University in Milwaukee. People will say to me, Well, whats your theory on who did it? And they look so disappointed when I say, Oswald did it all by himself.

That, of course, was also the conclusion of the presidential commission appointed a week after the assassination. Headed by Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, the commission announced its Oswald-acted-alone findings on September 24, 1964.

On that date, vigorous conspiracy theories commenced, and the whodunit debate has roiled ever since.

The Kennedy assassination really has achieved mystic significance, McAdams, 58, tells the Crime Library. In this era when conspiracy theories abound, says McAdams, The greatest and grandest of all conspiracy theories is the Kennedy assassination conspiracy theory.

McAdams says Oliver Stones film J.F.K. stirred the conspiracy pot by adding gravitas to Prosecutor Jim Garrisons fringe theory on the case. The movie still draws newcomers into the obsessive world of Kennedy assassination enthusiasts.

On one side are the conspiracy theorists, on the other the so-called debunkers. They argue with a fervor normally reserved for politics and religion.

Scores of books have been written about the assassination, and perhaps a hundred Web sites are dedicated to the subject, including one vast archive maintained by McAdams.

In these arenas, conspiracy theorists throw out questions, and debunkers try to respond.

Some questions are broad: Why did the Secret Service remove President Kennedy’s body from Dallas and transport it to Washington? Others are terribly specific, such as: “Why is the upper part of the right eye’s socket skull orbit missing from the X-ray that is supposed to be JFK’s?”

Dave Reitzes, 34, a writer who lives in Delaware, has been on both sides.

I was drawn into it by Oliver Stone’s movie in 1991, he writes in an e-mail interview. I was a rabid conspiracy theorist for eight or nine years, then did a hard about-face when I began to realize how wrong my thinking had been.

He says the conspiracies are propelled by disbelief that 10th-grade dropout Oswald–a silly little Communist, in the reported words of Jackie Kennedycould have killed a president; by a distrust of government, and by the poor work of mainstream journalists and historians who allow questionable theories to go largely unchallenged.

He adds, The truth is available to anyone who cares to study up on it. But those who fail to differentiate between evidence that is verifiable and the more popular varieties — i.e., unsubstantiated eyewitness claims, hearsay, rumor, and supposition — are going to forever doom themselves to chasing shadows, much like the hunters of flying saucers, Bigfoot, etc.

Reitzes says the conspiracy theories can be withering.

Of late, I confess I’ve found it hard to maintain much interest, he says. The seemingly endless springs of gullibility grow tiresome, and the theories certainly aren’t getting any more persuasive. If anything, they get more outlandish as the years go by.

One prominent conspiracy theorist, Barb Junkkarinen, agrees that far-out conjectures get in the way.

Unfortunately, what gets all the attention are the nuts on both sides, she says. Everyone (in the media) runs to them, and the rest of us suffer the consequences.

Junkkarinen, 52, who lives near Portland, Ore., has a particular interest and expertise in the medical aspects of the case, including bullet-wound details.

She doubts Oswald shot Kennedy. She believes instead that he was set up as a foil to a larger conspiracy, which was covered up by a panicked United States government.

Junkkarinen says she was drawn into the JFK assassination long before Oliver Stones film. (She admits it is an obsession; her e-mail name is barbjfk, and she notes with a laugh that her husband recently gave her a Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, the brand found near the assassins window roost at the Texas School Book Depository building in Dallas.)

For me, I love a mystery, Junkkarinen says. I grew up reading Nancy Drew and Trixie Belden. I think it was that and the medical evidence that sucked me into it.

She is an active member of a Web-based Kennedy assassination discussion group, attends JFK conferences and sometimes writes about the Kennedy evidence.

A lot of people want to place blame for who is responsible, she says. Im not sure that can be done, and Im not sure it matters. I think for me, if someone would come forward and say, There was a conspiracy and there was a cover-up, and now its such a mess it can never be untangled. That would satisfy me.

And why does it matter at this point?

I think it matters because Americans expect and deserve a true history, and I dont think we have that, Junkkarinen says. Thats the bottom line: History should be true.

McAdams, the Marquette professor, says Jack Ruby is largely responsible for fueling the suspicions of people like Junkkarinen.

Ruby did a tremendous amount to perpetrate the conspiracy theories, he says. Depriving American history and the American people of a Lee Harvey Oswald trial was a terrible thing.

But various government authorities can be blamed, as well.

First, Dallas police allowed Ruby access to Oswald at least twice. The department led a shoddy investigation in other ways, as well, calling into question the chain of evidence. The citys police chief leaped to the quick conclusion that Oswald was the assassin, then went before the media to announce his finding.

The Secret Service and Kennedys top aides spirited the presidents body out of Dallas just 100 minutes after he was declared dead. In Washington, a bumbling team of doctors performed a hack-job autopsy on what was perhaps the most precious corpse in modern American history.

The fumbled Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and the report that the Kennedy administration had contracted Mafia assassins to kill Fidel Castrooperating a damned Murder Inc. in the Caribbean, in the words of Lyndon Johnson–gave legs to the notion that the United States would do nefarious business with just about anyone for just about any purpose.

Suspicious doings, polluted evidence, the credibility gap, striking coincidences: For many, these factors make doubting seem more sensible than believing.

Junkkarinen, a doubter, uses the analogy of a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, which is complicated enough. But the box of the JFK assassination puzzle has 2,000 pieces. To solve it, you must first figure out which 1,000 pieces dont fit.

On the other hand, McAdams, the believer, says too many conspiracy theorists flyspeck just one inaccurate piece of the puzzle, then use that error as a basis to dismiss the entire Kennedy investigation.

The tactic has been known to work in the contemporary world of criminal justice: If the glove doesnt fit, you must acquit.

The tarmac at Love Field in Dallas bustled with limousines and police motorcycles on that November morning as the Secret Service and city cops readied what would become the most scrutinized motorcade in American history.

Sixteen cars, a dozen motorcycles and three buses were assembled to carry John F. Kennedy and his entourage to the Dallas Trade Mart, in the heart of downtown, where the president was scheduled to address civic leaders.

Air Force Two, carrying Vice President Lyndon Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, touched down at 11:30 a.m. after the brief flight from Fort Worth. Air Force One followed at 11:40 a.m. On board were Kennedy and his wife, Texas Gov. John Connally and his wife, Nellie, and U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough.

On hand at the airport was a small throng, including journalists and key Texas political supporters. Kennedy greeted Texas dignitaries in a receiving line. He made certain to acknowledge well-wishers who lined fences at the airport to get a look at the president and First Lady.

Kennedy was devoting two days to Texas as an early campaign trip that he hoped would rally the Lone Star States sometimes fractious Democrats around a single cause: his reelection.

The presence of Jackie Kennedy on the trip was carefully considered. Mrs. Kennedy had become an iconic figure in America, with a celebrity that rivaled her husbands. The presidents advisors had plotted slow-rolling motorcades in the three largest Texas cities in part to allow citizen-voters a glimpse of Americas elegant queen.

The Kennedys left Washington on the morning of Thursday, November 21, and flew to San Antonio. They were met there by Gov. Connally and Vice President Johnson, who joined the president in a motorcade downtown.

That afternoon the president flew to Houston, where another motorcade awaited. He spoke to a large crowd at Rice University Stadium, then attended a political dinner in Houston.

Late Thursday night, the Kennedys flew to Fort Worth, where they spent the night at the Texas Hotel. Friday morning, Kennedy attended a breakfast at the hotel and spoke to a crowd outdoors before leaving for Dallas.

He must have felt ill at ease after the two motorcades on Thursday. At the hotel, the Kennedys and Kenneth O’Donnell, special assistant to the president, had a foreboding conversation about the potential danger of motorcades.

ODonnell would tell the Warren Commission that the President said, If anybody really wanted to shoot the president of the United States, it was not a very difficult job. All one had to do was get in a high building someday with a telescopic rifle, and there was nothing anybody could do to defend against such an attempt.”

The Dallas motorcade set off from the airport just 10 minutes after the presidents jet landed.

The schedule allotted 45 minutes for the 10-mile trip from Love to the Trade Mart. The motorcade route had been well-publicized in the week before Kennedys visit. The presidents political handlers hoped for a huge show of support. Thats why he had gone to Texas, after all.

The motorcade left the airport and traveled along Main Street toward the tall buildings of downtown Dallas, where thousands of office workers would be free on lunch hour when the motorcade passed. Warren Commission investigators confirmed the motorcade route was chosen to maximize participation from citizens.

And that is what happened. The parade route was mobbed.

Police had manned all bridge overpasses and shooed away unauthorized individuals. But screening the crowd or searching buildings along the route for miscreants was impossible.

The convoy buzzed along Main Street at 25 to 30 miles an hour in the more sparsely populated outer reaches of Dallas. But even there a number of people waited to see the Kennedys, and the motorcade gradually slowed as it headed downtown.

The first car in the convoy, known as the pilot car, carried Dallas police officers. It stayed a quarter-mile ahead of the political parade that followed and was assigned to report signs of trouble.

Next came six motorcycles, then the lead car, an unmarked Dallas police vehicle driven by Police Chief Police Jesse Curry and occupied by Dallas County Sheriff J.E. Decker and Secret Service Agents Forrest Sorrels, of the White House detail, and Winston Lawson, special agent in charge of the Dallas office.

According to the Warren Commission report, The occupants scanned the crowd and the buildings along the route. Their main function was to spot trouble in advance and to direct any necessary steps to meet the trouble. Following normal practice, the lead automobile stayed approximately four to five car lengths ahead of the President’s limousine.

The presidential car, a specially designed 1961 Lincoln Continental convertible, was fitted with a futuristic plastic bubble that could protect the occupants from rain while allowing people along the motorcade route to get a good look at their dashing president and his lovely wife.

But the weather was fair, so the bubble had been removed. The plastic was not bullet-proof, in any case.

Kennedy sat in the right rear seat with his wife to the left. John and Nellie Connally were seated in front of them in a jump seat, with Nellie on the left.

Secret Service Agent William Greer drove the car, and Agent Roy Kellerman, head of the White House detail, rode shotgun. The limousine was fitted with running boards that allowed agents to ride beside the president, but Kennedy preferred to give citizens an unobstructed view during motorcades.

Four more motorcycles flanked the presidents car to keep the crowd back. Again, Kennedy had asked that the cycles lag back to give people a good view.

Behind the presidential limo was a 1955 Cadillac that carried eight armed agentsfour inside, four on the running boards. ODonnell and another aide rode in that car, as well. The agents on the running boards were assigned to hurry up to the presidential car any time it slowed to a stop or a walking pace.

Next in line was the vice presidents car, a four-door Lincoln convertible that carried the Johnsons, Sen. Yarborough and a Secret Service agent. A Texas highway patrolman drove.

Behind Johnsons Lincoln was a car driven by a Dallas cop that carried three more agents and Clifton Garter, assistant to Johnson.

And this was followed by the rest of the motorcade, including five cars with the Dallas mayor and other Texas politicians; the presidents physician, Admiral George Burkley; telephone and Western Union vehicles; a White House communications car; three cars of press photographers; a bus for White House staffers, and two press buses.

A Dallas police car and three more motorcycles brought up the rear.

In downtown Dallas, the motorcade slowed to 10 mph as the Kennedys and Connallys smiled and waved to the masses lining the route, a crowd estimated at a quarter-million. At Houston St., the motorcade turned right off Main, then left onto Elm to allow quick passage through Dealey Plaza to the Stemmons Freeway for the final leg of the trip.

At the corner of Houston and Elm stood a seven-story building leased to the Texas School Book Depository, which shipped schoolbooks in the southwest.

As the motorcade moved toward the Book Depository, Nellie Connally turned and remarked about the greeting that the Kennedys were receiving.

The governors wife said, “Mr. President, you can’t say that Dallas doesn’t love you.”

Kennedy replied, “That is very obvious.”

These were John Kennedys last words.

The motorcade was running a few minutes late.

As he was prone to do, Kennedy had twice ordered his limo to stoponce when he saw a man holding a sign inviting the president to shake his hand, and a second time to greet a Catholic nun and a group of schoolchildren.

The dense crowds downtown had also slowed the pace of the motorcade.

The presidents car was crawling at 11 mph past the Texas School Book Depository at precisely 12:30 p.m., the hour the president was due at the Trade Mart.

Rifle shots rang out.

One slug passed through the president’s neck, according to the Warren Commission. A second, subsequent, lethal bullet shattered the right side of his skull. Connally was wounded in his back, the right side of his chest, right wrist and left thigh.

Secret Service agents rushed to the limousine.

Jackie Kennedy cried out, “Oh, my God, they have shot my husband. I love you, Jack.”

Agent Kellerman, in the presidents car, radioed ahead to Police Chief Curry, who led a high-speed dash to Parkland Hospital, 4 miles away.

There was no saving the president, of course. He was declared dead 30 minutes after the shooting. An emergency operation was conducted on Connally; he would survive.

By 2:15 p.m., Kennedys body was in a casket and loaded on Air Force One for the return flight to Washington.

But the takeoff was delayed while aides arranged an urgent ceremony to ensure continuity of government.

Federal Judge Sarah Hughes, appointed by Kennedy in 1961 as the first female U.S. District Court judge in Texas, hurried to Love Field.

At 2:38 p.m., just before the jet departed for Washington, Hughes swore in Lyndon Johnson as the 36th President. He was flanked by his wife and Mrs. Kennedy during the brief, solemn ceremony.

Judge Hughes later said, I thought she (Jackie Kennedy) showed remarkable poise. She didnt weep. She didnt say a word. Her poise was outstanding. Her courage was outstanding.

Within minutes of the assassination, several eyewitnesses had pointed to the Book Depository building as the source of the gunshots.

One witness, Howard Brennan, said he noticed a man at a window of the building several times just before the motorcade passed. Brennan said he looked up after hearing the first shot and saw the same man fire a rifle, then disappear. Based on Brennans account, police at 12:45 p.m. broadcast a description: white male, slender, 165 pounds, 5-foot-10.

Cops flooded the building, and near a sixth-floor window they found three shell casings and a bolt-action rifle with a telescopic sight.

At 1:15 p.m., Dallas Patrolman J.D. Tippit noticed a man near 10th and Patton streets, a couple of miles from the assassination scene, who matched the suspects description. Tippit called the man to his patrol car. After a brief exchange through the window, the cop got out, apparently to question the man more closely.

The man pulled a pistol and fired four shots that struck and killed Tippit.

A dozen people witnessed the shooting. Someone called police, and heads turned to watch as radio cars raced to the location with sirens crying.

News of the presidents shooting had Dallas residents on high alert, and several people noticed a suspicious man duck into a doorway eight blocks from the shooting scene as cop cars passed.

One such witness was Johnny Brewer, a shoe store manager, who saw the man slip into the Texas Theater.

“He just looked funny to me, Brewer told the Warren Commission. His hair was sort of messed up and looked like he had been running, and he looked scared, and he looked funny.”

Brewer spoke with the theaters box office clerk, Julia Postal. He told her, “I don’t know if this is the man they want…but he is running from them for some reason.”

Postal called police.

More than a dozen officers converged on the theater. They ordered the house lights turned up, and Brewer pointed out the suspicious character. As cops moved in, the man brandished his pistol but was subdued before firing a shot, although some officers said they heard the click of a misfire.

Eyewitness Brewer said fists flew while the suspect was being arrested. He heard one cop say, Kill the president, will you?

An officer later said the suspect was cursing a little bit and hollering police brutality.

The suspect was 24 years old, 5-foot-9 and 150 pounds. His name was Lee Harvey Oswald.

A misfit Marine Corps vet, the native of New Orleans had been hired as a $1.25-an-hour order-filler at the Texas School Book Depository six weeks earlier.

En route to the police station, Oswald asked over and over, “Why am I being arrested?”

Oswald was taken to the Dallas Police and Courts Building downtown.

At 7:10 that evening, a justice of the peace visited to arraign Oswald on charges that he killed Patrolman Tippit. Six hours later, at 1:30 a.m. November 23, he was arraigned by the same justice in the murder of Kennedy.

Oswald was questioned at Dallas police headquarters for some 12 cumulative hours over the two days following his arrest. Capt. J.W. Fritz of the Dallas police homicide bureau conducted most of the interrogation.

FBI and Secret Service agents often were present and sometimes asked questions of Oswald.

The Warren Commission said, Throughout this interrogation he denied that he had anything to do either with the assassination of President Kennedy or the murder of Patrolman Tippit.

Nonetheless, Oswald faced a daunting catalogue of evidence:

The Smith & Wesson .38 Special used to shoot Tippet was wrested from Oswald during his arrest.

Nine witnesses identified Oswald as the cops killersix in person, three by photographs.

He had access to the sixth floor of the Book Depository building, and witnesses saw him there prior to the shooting of Kennedy.

Forensic evidence indicated he had been at the window where the shell casings were found, and his palm print and clothing fibers were found on the rifle used to shoot Kennedy and Connally. (The purity of this evidence has been the source of great debate.)

The gun had been purchased by someone using the name A. Hidell, an alias that Lee Oswald had used frequently.

Investigators found two photographs showing Oswald holding the rifle and the pistol.

At about 11 a.m. Sunday, November 24, Oswald was to be transferred from the Police and Courts Building to the Dallas County Jailstandard procedure once a crime suspect had been charged with a felony.

But the transfer was anything but routine.

Anonymous threats against the accused assassin had been phoned in to authorities, and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover later said that he had sent a message to Police Chief Curry asking that Oswald be afforded the utmost security.

Curry would claim he never got the message.

Just the same, it surely had occurred to Dallas cops that Oswald might be endangered. He was being moved, after all, in an armored truck.

Curry decided to make the move of Oswald a media event by staging a photo opportunity in the basement of police headquarters.

He indicated to reporters that the transfer would happen after 10 a.m. Sunday, November 24.

A crew of 14 cops cleared the basement of all but police personnel at 9 a.m. Sentries were placed at the six doors to the basement area and at the tops of two auto ramps connecting the basement to streets above.

After the basement was secure, cops allowed journalists to re-enter. The scribes and shutterbugs were positioned opposite the door through which Oswald and his escorts would emerge. Uniformed cops and plainclothes detectives also poured into the basement for a glimpse at the accused assassin.

By 11:20 a.m., an estimated 50 newsmen and 75 cops were assembled waiting for Oswald.

On live national television, Oswald walked through the doors surrounded by lawmen. After he had walked perhaps 10 feet, a stout man stepped between newsman at the edge of the crowd. He extended his right hand, which gripped a Colt .38-caliber revolver, and fired a single fatal bullet into Oswald’s abdomen, as the Warren Commission report put it.

The man was soon identified as Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub owner who had many friends in the citys police department.

But he claimed he hadnt been tipped off to the transfer or given special access by a friendly cop. He said he simply walked down the auto ramp from Main Street.

As the Warren report said, The Dallas Police Department, concerned at the failure of its security measures, conducted an extensive investigation that revealed no information indicating complicity between any police officer and Jack Ruby. Ruby denied to the Commission that he received any form of assistance.

Further investigation would reveal that Ruby didnt really need one cops help. He had been given the run of police headquarters simply by showing up.

The Warren Commission determined that Ruby, known to act impulsively, closed his nightclub on the night of Kennedys assassination and attended a memorial service at his Dallas synagogue. Driven to contribute in some way to the investigation, he stopped at a deli and bought sandwiches and sodas for cops.

He then went to police headquarters, where he left the food in his car and walked into the building alongside two news reporters, then rode an elevator to the third-floor pressroom, down the hall from where Oswald was being grilled.

Although he had no press credential, Ruby told anyone who asked that he was a translator for the Israeli media. Film of a press conference late Friday night at which Oswald was presented to the media showed Ruby standing on a table beside reporters.

A Dallas detective, Augustus Eberhardt, recalled having a brief conversation with Ruby, who commented that it was hard to realize that a complete nothing, a zero like that, could kill a man like President Kennedy.

After the press conference, Ruby buttonholed District Attorney Henry Wade and Justice of the Peace David Johnson, who had arraigned Oswald. He introduced himself as a nightclub owner, and later helped arrange a phone interview with Wade for KLIF radio in Dallas.

Ruby then drove to the KLIF studio, distributed his sandwiches to staffers and hung out for a couple of hours. He later stopped at the Dallas Times-Herald building, where he spoke with several composing room employees about seeing Oswalda little weasel of a guy, as he put itat the press conference.

On Sunday morning, November 24, Ruby showed up in downtown Dallas just before the Oswald transfer.

He parked his car near police headquarters and opened the trunk, where he left his billfold and the cars ignition key. He then tucked into his suit pocket the revolver he normally kept in a bank moneybag in the trunk.

He walked down the block to a Western Union office and sent a $25 wire transfer to one of his nightclubs dancers, who was stranded in Fort Worth.

Ruby claimed he then saw a bustle at police headquarters and wandered over to see what was happening.

Perhaps his timing was an educated guess. More likely, he had been tipped off to the time of the suspects transfer; some have claimed the tipster was his pal W.J. Blackie Harrison, a Dallas police officer.

Whatever the case, he apparently managed to walk down the auto ramp into the basement of the law enforcement building, where he shot Oswald.

He gave several explanations of why he did it:

He wanted to be a hero.

He wanted to prove that Jews have guts.

He wanted to spare Jackie Kennedy the heartache of returning to Dallas for legal proceedings against Oswald.

He told the Warren Commission he was overwhelmed by the emotional feeling…that someone owed this debt to our beloved President to save her the ordeal of coming back. I don’t know why that came through my mind. Ruby swore he was not part of a conspiracy to silence Oswald.

Ruby was charged with murder and stood trial in February and March 1964. His attorney, Melvin Belli, argued for an insanity verdict, but the jury convicted Ruby and condemned him to die.

Ruby won an appeal on grounds of fairness because he had been denied a change of venue. A Texas court ordered a new trial, but Ruby died of cancer on January 3, 1967, before it could be held.

Although most Americans, still numb over the assassination, watched slack-jawed as Oswald was gunned down on TV, some reckoned that Ruby had done the nation a favor by sparing America a circus trial.

In the view of Dallas cops, they had their man in Lee Oswald, after all.

Capt. Fritz, the suspects chief interrogator, told reporters on the day after Kennedys murders that the case against Oswald was cinched. Chief Curry added, We are sure of our case. He went on to offer wildly premature statements about evidence against the accused.

Yet the trial might have been a fiasco.

A month after Oswalds murder, the American Bar Association said, Widespread publicizing of Oswald’s alleged guilt, involving statements by officials and public disclosures of the details of ‘evidence,’ would have made it extremely difficult to impanel an unprejudiced jury and afford the accused a fair trial.”

He apparently had requested but was denied legal representation during his long hours of interrogation, and no notes were kept of his statements during the questioning.

Legal technicalities such as fair trial aside, the Warren Commission concluded that Dallas police did, indeed, have their man.

The report said,

On the basis of the evidence…the Commission has found that Lee Harvey Oswald (1) owned and possessed the rifle used to kill President Kennedy and wound Governor Connally, (2) brought this rifle into the Depository Building on the morning of the assassination, (3) was present, at the time of the assassination, at the window from which the shots were fired (4) killed Dallas Police Officer J. D. Tippit in an apparent attempt to escape, (5) resisted arrest by drawing a fully loaded pistol and attempting to shoot another police officer, (6) lied to the police after his arrest concerning important substantive matters(and) possessed the capability with a rifle which would have enabled him to commit the assassination. On the basis of these findings the Commission has concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald was the assassin of President Kennedy.

JFK Assassination

Lee Harvey Oswald

Even aside from his role as political assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald surely led one of the more unusual 24-year-long lives in history.

He tagged along with his itinerant mother for the first 15 years; developed a fascination for communism at 16; dropped out of school as a high school sophomore; joined the Marine Corps at 17; taught himself rudimentary Russian; got an early military discharge; emigrated to Russia at age 20 and attempted to renounce his U.S. citizenship; married a Russian woman and fathered a daughter; got bored with his Soviet factory job and returned to the United States; tried to shoot a controversial general; threw himself into the pro-Castro movement.

Oswald went through life with a simmering sense of outrage.

He was born to a troubled life on October 18, 1939, in New Orleans.

His mother, Marguerite, was seven months pregnant with Lee when her husband, Robert, died of a heart attack.

Lee and his two siblings–one full brother and one half-brother from the brief first marriage of his motherspent time in orphanages as children because Mrs. Oswald was unable to support them.

The family moved to Dallas and then Fort Worth in the mid-1940s as Mrs. Oswald pursued a new romance and marriage with Edwin Ekdahl, an electrical engineer. But the marriage soon was on the rocks.

Lee lived with Marguerite at various places in the Dallas area during the formative years after the breakup. He attended school but did not distinguish himself, struggling especially in math and spelling.

As the Warren Commission reported, Lee is generally characterized as an unexceptional but rather solitary boy during these years. His boyhood neighbors later would use unflattering words and phrases to describe him: bad kid, quick to anger, mean.

At age 13, Lee moved to New York with his mother to live near relatives, but his behavior took a turn for the worse there. He became a chronic school truant and was increasingly difficult for his mother to control. After appeals for help from Marguerite, young Oswald was ordered to undergo testing at a youth detention facility.

Staff members indicated that Lee was a withdrawn, socially maladjusted boy whose mother did not interest herself sufficiently in his welfare and had failed to establish a close relationship with him, according to the Warren report.

In 1954, Lee and his mother returned to New Orleans, where he attended school more regularly for a year, then dropped out in tenth grade, just before his 16th birthday.

The two moved once again to Fort Worth as Lee bided time until his 17th birthday, when he intended to enroll in the Marine Corps.

On October 3, 1956, a few weeks before that birthday, he wrote a letter to the Socialist Party of America based on a coupon he clipped from a magazine:

Dear Sirs:

I am sixteen years of age and would like more information about your youth League, I would like to know if there is a branch in my area, how to join, etc., I am a Marxist, and have been studying socialist principles for well over fifteen months I am very interested in your Y.P.S.L.

Sincerely

Lee Oswald

Three weeks later, he enlisted in the Marines.

Oswald qualified as a sharpshooter rifleman during basic training, and he spent much of his time aboard ships in the Far East.

He earned a reputation as an oddball among his fellow jarheads, who nicknamed him Oswaldskovich for his fascination with Russia.

Oswald studied the Russian language, read Russian literature and played recordings of Russian music in the barracks. He often responded with da or nyet instead of yes or no and addressed fellow Marines as comrade, according to the Warren Commissions book-length biography of Oswald.

He sometimes debated with his peers about the moral superiority of Marxism and communism, which he called “the best system in the world,” according to one Marine who knew Oswald. He also told peers that he supported the revolutionary Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

He buried his nose in books that concerned political ideology: Das Kapital, Animal Farm and 1984.

Oswald was discharged in September 1959. Within a month, he traveled by ship to France, flew to Helsinki, entered Russia on a tourist visa. A few days later, on his 20th birthday, he began telling any Russian who would listen that he wished to defect.

He apparently believed this would be a momentous international event. He kept notes of his defection in a binder he labeled Historic Diary.

But Russia initially rejected him, and Oswald responded by slashing a wrist in an apparent suicide attempt. The Russian government then ordered him confined to a psychiatric hospital.

Seeing that the young man was serious, Russia reconsidered, and after a series of interviews with American and Russian officials he was allowed to defect.

Marguerite Oswald learned that her son was in Russia when she read about his defection in a Fort Worth newspaper.

A few weeks after his arrival in Russia, Oswald sat for an interview with an American reporter, Aline Mosby of United Press International.

He said America was a nation of the rich and the poor while the Marxist ideology looked after all citizens equally. He told Mosby that he had been introduced to Communist political theory at age 15, while living in New York, when a woman handed him a pamphlet about the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were executed on charges of wartime espionage.

It is not clear what sort of life Oswald expected in Russia, but he grew disenchanted quickly.

He was sent to Minsk, 450 miles southwest of Moscow, and assigned to a factory job. A year later, in January 1961, he made this entry in his diary, with his typical misspellings:

I am starting to reconsider my desire about staying. The work is drab. The money I get has nowhere to be spent. No nightclubs or bowling allys, no places of recreation acept the trade union dances. I have had enough.”

He spent the ensuing year appealing to the Russian and American bureaucracies to secure reentry into the United States. He wrote indignant letters to American authorities, including one to U.S. Sen. John Tower of Texas that urged the senator to raise the question of holding by the Soviet Union of a citizen of the U.S., against his will and expressed desires.”

Remarkably, he also wrote an appeal for help to Texas Gov. John Connally, the same man he would shoot in the Kennedy motorcade.

Meanwhile, Oswald met a Russian love interest, Marina Prusakova, in March 1961, and they were married just weeks later. She gave birth to their daughter, June, in February 1962.

Four months later, the U.S. and Russian governments finally relented and allowed Oswald and his family to leave. They traveled by ship from Europe to New York, then flew to Fort Worth on June 14, 1962.

But the return to his native land did not ease Oswalds listlessness and animosities. FBI agents who debriefed him about his time in Russia described him as arrogant and insolent.

He tried working but couldnt hold a steady job, and he fiddled with a manuscript about his Soviet ideological dalliance.

His marriage grew increasingly tempestuous, and he began beating Marina. The couple socialized for a time with expatriate Russians in Dallas, but Oswald was soon ostracized for his anti-American carping, his egocentricity and his treatment of his wife.

The couple separated and reconciled a number of times, and Marinadissuaded from learning English by her husband–was taken in by a series of friends.

Meanwhile, Oswald threw himself ever more deeply into political ideology. He subscribed to Soviet periodicals and corresponded with the Communist Party USA and the Socialist Workers Party.

In early 1963, Oswald bought a pistol and a rifle via mail order under an alias, Alek Hidell.

On April 10, someone fired a rifle shot in Dallas that narrowly missed the head of Edwin Walker, a notorious anti-Communist. Walker had resigned from the U.S. Army in 1961 after being accused of indoctrinating soldiers with literature from the right-wing John Birch Society.

The shooting went unsolved until Oswald was arrested and investigators found a note he wrote to Marina in Russian that explained what she should do if he was arrested. The Warren Commission said Oswald fired the shot at Walker, although many question that conclusion.

Days after the Walker assassination attempt, Oswald traveled by bus to New Orleans, apparently hoping to find work in his hometown. He rented an apartment and sent for his wife and daughter after landing a $1.50-an-hour position at a coffee mill.

As usual, he soon lost the job and began collecting weekly government unemployment payments.

He found a new cause to occupy his idle time: the pro-Castro Fair Play for Cuba Committee.

Oswald applied for and received a new passport, hoping to travel to Cuba to meet Castro and join his revolution.

He formed an informal New Orleans branch of Fair Play and spent a night in jail following a street dispute with anti-Castro Cuban exiles. He appeared on TV and in a radio news report for his pro-Castro leafleting, and he wrote a series of letters trumpeting his work for the cause to the national Fair Play organization and the Communist Party USA.

In late September, Oswald rode a bus from New Orleans to Houston, continued west to Laredo, then crossed the border into Mexico for a 20-hour bus ride to Mexico City.

Once there, Oswald began seeking permission to travel to Cuba. But his American passport was invalid for travel to the country, so he once again cast himself against bureaucracies.

He repeatedly visited the Mexican, Cuban and Russian embassies, seeking a visa to Cuba. He was turned away each time.

On October 3, he returned crestfallen to the U.S. and made his way back to Dallas. He was hugely disappointed by his failed Cuban odyssey, said his wife.

He wrote a scorching letter to the Soviet embassy in Washington, charging a gross breach of regulations by the Mexico City Cuban embassy, according to the Warren Commission.

In Dallas, Oswald persisted in his rabble-rousing, attending a John Birch meeting for reconnaissance purposes, then attending an ACLU meeting at which he reported what he had heard at the Birch gathering.

He lived apart from Marina in a series of cheap rooming houseshis last an $8-a-week place at 1026 N. Beckley Ave. where he registered as O.H. Lee.

A family friend said Oswald was discouraged by more than his failure to get to Cuba when he returned to Dallas: Marina was pregnant. He had failed to support one child, let alone two.

He lost one job prospect due to a poor reference, then took yet another menial job on October 15 at the Texas School Book Depository on a referral from a family friend. He was assigned to work the day shift, and he spent much of his time on the sixth floor, where a window afforded him a fine view of Dealey Plaza not quite six weeks later when President Kennedys motorcade passed.

The Warren Commission report featured a 15,000-word biographical portrait of Jack Ruby that is remarkable for its detailsome of it remarkably peculiar.

One brief section cogitates over whether Ruby was a homosexualapparently based on anonymous statements of acquaintances that he spoke with a lisp, acted effeminately and sometimes spoke in a high-pitched voice when angry.

The Warren sleuths managed to discern that Ruby had had an 11-year relationship with a woman. The report concluded, The record indicates that Ruby sought and enjoyed feminine company.

Another section reviewed Rubys affection for dogs. He owned several and referred to them as his children. The report noted Ruby became extremely incensed when he witnessed the maltreatment of any of his dogs.

Jack Ruby was born Jacob Rubenstein in Chicago in 1911, one of eight children of Jewish parents who had immigrated from Poland.

His mother was illiterate, his father a heavy drinker and member of the carpenters union, although he rarely worked. Joseph Rubensteins drinking and chronic unemployment drove the couple apart in 1922.

Son Jack soon landed in juvenile detention as truant from school and incorrigible at home. He spent time in foster homes, as did several of his siblings. The drain of supporting eight children overwhelmed Jacks mother, Fannie, and she would later spend time in mental hospitals.

Jack made it through eighth grade, then found himself on Chicago streets attempting to provide for himself and other members of his family, as the Warren report put it. He earned money by scalping tickets to sporting events and by selling sports-related novelties, such as Cubs banners.

In 1933 Ruby moved to California to find Depression-era work. Among other things, he sold a handicappers tip sheet at two race tracks, Santa Anita in Los Angeles and Bay Meadows in San Francisco. He also worked as a waiter and sold newspaper subscriptions door-to-door.

Ruby returned to Chicago in about 1937 and spent four lean years before founding the Spartan Novelty Co., which sold small cedar chests filled with candy and punchboard lottery tickets. He later sold a plaque commemorating Pearl Harbor and a bust in honor of Franklin Roosevelt.

One acquaintance told Warrens investigators that Ruby was a cuckoo nut on the subject of patriotism. Others said he was motivated purely by money.

Although just 5-foot-9, Ruby was a stout, 175-pound fitness buff.

Friends and siblings said he had a volatile temper; he grew up with the nickname Sparky because his rage would strike like lightning.

The umbrage that Ruby felt over mistreatment of canines carried over to other underdogs, as well.

He often picked fights over slurs or attacks against Jews, blacks and women, and he would put up his dukes against anyone spouting pro-Nazi or anti-Semitic sentiments.

Yet Ruby was not eager to join the war effort.

He sought a draft deferral based upon his age (30 in 1941), and he faked a hearing loss after the age deferral was abolished. He was drafted into the Army Air Forces in 1943 and spent three uneventful years at military bases in the south.

He returned to Chicago in 1946 and formed a mail-order novelties business with his brothers. (They legally changed their name from Rubenstein to Ruby, fearing some Americans would not do business with Jews.)

The brothers bought out Jack Ruby in 1947, and he moved to Texas with a $14,000 stake to join a sister, Eva Grant, who was running a Dallas nightclub.

Ruby would spend the next 16 years running nightclubs, saloons and strip jointsthe Silver Spur Club, the Ranch House, the Vegas Club, the Sovereign Club and, finally, the Carousel Club.

The Carousel was a four-stripper burlesque joint in downtown Dallas. Ruby ran the place with an iron fist, and most employees didnt last long.

He argued about work rules with his musicians. He wrangled over wages with the union that represented his showgirls. He battled the government over his accounting practices (strictly cash and usually kept in the trunk of his car or in his hip pocket) and delinquent taxes. And as the clubs owner/bouncer, he fought with unruly customers.

The Carousels regular clientele included a couple dozen Dallas cops, a few of whom worked for Ruby and one of whom married a stripper from the club.

The Warren Commission reported, Ruby’s police friendships were far more widespread than those of the average citizen.

The police friendships did not keep his record spotless. Ruby was arrested eight times before shooting Oswald: for disturbing the peace in 1949; for carrying a concealed weapon in 1953 and 1954; for violating state liquor laws in 1954; for allowing dancing after hours in 1959 and 1960; for simple assault in 1963, and for ignoring a traffic summons in 1963.

The government also hounded Ruby for delinquent taxes, including about $5,000 in income tax and $40,000 in federal excise taxes he had neglected to charge patrons because he claimed his establishments were restaurants, not cabarets.

As a strip club owner, Ruby became acquainted with many of the more unsavory individuals of the Dallas underworld.

The Warren Commission report said that while he was friendly with numerous underworld figures, evidence does not establish a significant link between Ruby and organized crime.

This odd canard has been a favorite bone of contention used by conspiracy theorists against the Warren Commission.

Ruby probably was allowed to stay in business by paying off the Dallas mob, then led by Joseph Civello. Among his closest friends was Civellos No. 2 lieutenant, and Ruby also was tight with three brothers who led another Dallas Mafia unit.

Here are thumbnails of some of the other key figures in the Kennedy assassination:

Fidel Castro

Born to a reasonably well-off Cuban farm couple, Castro was educated by Jesuits, studied law and married into one of the island nations wealthiest families. Yet he was a revolutionary by age 21 and dedicated himself to the overthrow of the U.S.-friendly dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista.

As a young rabble-rouser, Castro was a reform-minded nationalist, not a Communist. He was imprisoned in 1953 but was allowed to go into exile in Mexico two years later. He returned to his homeland in 1956 and led a guerrilla war that led to Batistas overthrow on January 1, 1959.

The CIA under President Eisenhower began formulating a plan to invade Cuba and assassinate Castro, and the scheme carried over into the Kennedy administration. The CIA apparently went so far as to employ hired Mafia assassins to carry out the plot.

But the plot stalled, and in 1962 President Kennedy approved a CIA-led invasion at Bay of Pigs, Cubaa notorious U.S. failure and debacle.

Increasingly, the United States grew convinced that Castro was playing footsy with the Soviet Union, its Cold War archenemy. U.S. fears that Russia would use Cubajust 90 miles from Key West, Florida–as a staging ground for nuclear warheads led to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1963, a seven-day staredown between Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.

Castro endures today at age 78, having outlived the Soviet Union and outlasted 10 U.S. presidents.

Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Johnson was a pragmatist. For one thing, he was smart enough to know that he didnt know everythinga trait that not all politicians share.

Born in 1908 west of Austin, Texas, he taught high school, then went to Washington in 1931 to work as secretary for a newly elected congressman. Before he was 30, Johnson was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1937 to replace a Texas congressman. He served 11 years there and was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1948, where he became an influential dealmaker as majority whip, minority leader and, in 1955, majority leader.

Johnson and Kennedy, the top candidates for the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination, agreed to become running mates and pool their support. The deal paid off as they eked out a victory over the Republican ticket of Nixon-Lodge.

Johnson was sworn in as Americas 36th president two hours after the assassination of Kennedy. He was elected to the office in 1964 but stepped aside in 1968. He died on his ranch in 1973.

Jim Garrison/Oliver Stone

Garrison was the New Orleans district attorney who in the late 1960s announced he had solved the Kennedy assassination. He brought conspiracy charges against a Louisiana businessman, but the man was acquitted by a jury in less than an hour after a 34-day trial that was as much a circus as a legal proceeding.

Garrison spent 12 years as district attorney and later was elected a Louisiana appeals court judge. But he had slipped into relative obscurity by 1991, when filmmaker Stone released J.F.K., which treated the prosecutor as a hero battling a sinister government. (He had a bit part in the film, which was based on one of three books Garrison wrote about the assassination.)

He died in 1992.

As the New York Times wrote in his obituary, Many public officials and assassination experts dismissed Mr. Garrison’s theories as bizarre, irresponsible and an effort to get publicity. But interest in his accusations continued among assassination buffs as doubts grew about the accuracy and completeness of the official findings.

Abraham Zapruder

Zapruder, 59, a Dallas clothing manufacturer, was among the throng on Dealey Plaza on the day of the Kennedy assassination. His firm, Jennifer Juniors Inc., operated out of a building opposite the Texas School Book Depository.

A camera buff, he set up his Bell & Howell Zoomatic 8 mm on a foot-high concrete abutment adjacent to the grassy knoll of Dealey Plaza to record moving images of the presidents visit to Dallas.

Some 75 amateur and professional photographers were shooting the Kennedy motorcade as it passed the Book Depository. But his timing, the quality of Zapruders camera and the clarity of images from his elevated vantage point made his footage an invaluable, albeit horribly graphic, historical record.

He shot 26 seconds of film at 18.3 frames per second. The first 7 seconds show the lead motorcycle escort. After a pause, the last 19 seconds show Kennedy and Connally being shot. Images from those 354 frames appeared in a special edition of Life magazine that was on newsstands just days later.

Both believers and doubters in the lone-assassin construct use the Zapruder film to bolster their arguments.

Zapruder, who died in 1970, and his heirs earned a fortune from the film. Zapruder was paid $150,000 from Life magazine, and his family was paid nearly $1 million in various usage rights before 1996, when the film was seized by the U.S. government. In 1999, an arbitration panel ordered the government to pay the family $16 million for the film, which is now housed in the National Archives.

Commander James Humes

Although his name is not as widely known as other Kennedy assassination figures, Dr. Humes played a big role in the perpetration of conspiracy theories.

He was the military doctor who performed the Kennedy postmortem at Bethesda Naval Hospitalan autopsy that professional pathologists later called a forensic disaster.

Humes, then 38, was chief of anatomic pathology at the hospital and director of the laboratories at the National Medical Center.

Yet the Kennedy case was his first gunshot-wound autopsy, and he did a slipshod job. He later said he had been ordered only to look for bullet fragments, not to conduct a full forensic pathological exam.

Photos taken during the exam were dark and amateurish. Humes said he discarded his notes kept during the autopsy because they were bloody.

Humes retired in 1967 and became clinical professor of pathology at Wayne State University School of Medicine. He died in 1999.

Authors

Scores of writers have taken on the Kennedy assassination case. Some were serious researchers, some were cranks, and some were shysters. Nearly any JFK book can be assured of sales-inducing publicity, and that fact is not lost on publishers. Among the noteworthy authors:

- David S. Lifton. His 1981 book, Best Evidence: Disguise and Deception in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, remains a favorite of conspiracy theorists.

- James Garrison. The New Orleans DA touted his own theory and tooted his own horn in On the Trail of the Assassins: My Investigation and Prosecution of the Murder of President Kennedy.

- Patricia Lambert. A conspiracy believer, she took on Garrison and Stone in her 1999 book False Witness: The Real Story of Jim Garrison’s Investigation and Oliver Stone’s Film JFK.

- Gerald Posner. Many conspiracy believers still gnash their teeth at the mention of Posners Case Closed, a 1995 bestseller that attempted to debunk conspiracy theories and offered a self-assured version of the lone-gunman scenario.

- Jim Marrs. The Dallas journalist brought together a compendium of conspiracy theories, including some far-out varieties, in his 1989 book, Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy.

- Harrison Livingstone and Robert Groden. Their book High Treason: The Assassination of JFK & the Case for Conspiracy was originally published in 1980 and updated with new evidence of a conspiracy in 1996.

So who killed John Kennedy?

The usual suspects are so numerous that whatever group you want to have a grudge against, you can pick your case based on the Kennedy assassination, says John McAdams, the Marquette professor. Anything is possible to believe if you are willing to take the most unreliable evidence or most unreliable inferences and run with them.

Here is a short list of suspects and theories.

Lee Harvey Oswald, Lone Gunman

The best argument for the Warren Commissions controversial conclusion may be the serendipity through which Oswald landed a job at the Texas School Book Depository weeks before the murdera second-hand referral. Simmering with anger about Cuba, Oswald learned that Kennedys motorcade route would pass by his building. He secreted a rifle into the building, took a place at a sixth-floor window and fired the shots that killed the president and injured Gov. Connally, believers say.

Second Unidentified Assassin on the Grassy Knoll

The notion of a second assassin or an assassination team at Dealey Plaza has been fomented over the years by suspicious shadows, gunman-like silhouettes and puffs of smoke that turn up in moving and still pictures shot by witnesses on the day of the Kennedy murder. These photographic hieroglyphs have been deciphered since the day after the shooting, and figures such as Black Dog Man and Umbrella Man are totems among both doubters and believers. Oliver Stone used the mysterious Umbrella Man in J.F.K. to signal the assassination team by pumping his umbrella up and down. The film left out one fact: the Umbrella Man had long ago been identified, questioned and cleared of having any part in the assassination.

The Cubans

The simplest Cuba theory is that Fidel Castro ordered Kennedy murdered because Kennedy had tried to have him murdered. In a variation, exiled Cubans who were angered at Kennedys failure in the Bay of Pigs invasion arranged to have him killed. And in a second version of that variation, the same right-wing Cubans ordered the murder because Kennedy had resolved the Cuban missile crisis by promising the Soviets that he would keep his hands off Castro. Oswald served as a foil to the Cubans, and Rubys job was to silence him.

The Kennedy-for-Castro postulate had a marquee believer: Lyndon Johnson. Six months before he died, Johnson told a journalist, I never believed that Oswald acted alone, although I can accept that he pulled the trigger. He said he believed Castro ordered the retaliatory murder.

The Cuban conspiracy theories gained weight because Oswald adored Castro and had tried to travel to Cuba not long before the assassination, and because Jack Ruby had visited the island nation in 1959. Mere coincidences, say the lone-gunman believers. Impossible coincidences, say the doubters.

The KGB

Under this theory, Soviet agentsagain, using Oswald as a foilkilled Kennedy because the president had embarrassed Premier Nikita Khrushchev in the missile crisis staredown. Debunkers dismiss this scheme since Kennedy had promised a hands-off-Cuba policy and had made other concessions that cast Khrushchev as a clever negotiator, not a failure. Conspiracy theorists happily note that Oswald had lived in the Soviet Union during a defection dalliance, spoke a little Russian and was obsessed with Russian literature and music.

LBJ

Lyndon Johnson is a seminal figure in any number of the conspiracy theories. As noted, he believed Oswald was a puppet for Castro. New Orleans DA Jim Garrison also fingered Johnson as a marionette pulling strings behind Garrisons personal conspiracy theory. He played a role in the KGB conspiracy theory, as well, by ordering the Warren Commission to leave that stone unturned, according to adherents, when it learned of a Soviet connection to the murder.

In newly released telephone recordings made during his presidency, Johnson sounded flummoxed and frustrated as various aides, politicians and newsmen briefed him on conspiracy theories about the assassination. But the subject regularly came up in the Oval Office.

In a 1967 conversation with Attorney General Ramsey Clark, Johnson referred to the CIAs covert efforts to kill Castro.

He said, Its incredible. I dont believe theres a thing in the world to it, and I dont think we oughta seriously consider it. But I think you oughta know about it.

Which proved, above all else, that even the president might not know everything the government is doing.

The Mafia

The Mafia liked Kennedys religion but hated his politics.

The president and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, had pushed for probes of union racketeering, angering Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa. His appeasement deal with Nikita Khrushchev to keep U.S. hands off Cuba under Castro also stuck in the craw of the mob, which had financial interests in Havanas casinos, which were popular with Americans before the revolution. And then there was the bizarre plot arranged by the CIA to use Mafia hitmen to whack Castro. Some believe the Mafia got angry when the Kennedys became impatient and called off the mob goons. Lastly, there may have been a complicated romantic entanglement since mobster Sam Giancana and Jack Kennedy reportedly shared the same mistress.

Whatever a doubters mob conspiracy theory of choice, Oswald served as a Mafia foil, and Jack Ruby, the Dallas nightclub owner who was on friendly terms with organized crime, was the wing man in the cover-up.

The FBI

J. Edgar Hoover had been kept informed of the whereabouts and activities of Lee Oswald. The agency knew he had subscribed to Commie publications, was active in the pro-Castro Fair Play for Cuba Committee and had traveled to Mexico in a failed attempt to gain access to Cuba. An FBI agent spoke with an Oswald acquaintance just two weeks before the assassination, and Oswald had written to the Soviet Embassy in Washington to complain of FBI harassment.

Why such interest in a small fry Red, doubters ask. Believers reply that the FBI had a remarkable ability to track a wide breadth of suspected enemies during the Cold War era, and Hoover took a personal interest in a mind-boggling number of those cases.

The Garrison/Stone Theory

Jim Garrisons wildcat theory of the JFK assassination was a mishmash of international and political intrigue. He fingered virulent anti-Communist, anti-Castro zealots in the Central Intelligence Agency for plotting the murder because the president was soft on Redsas witnessed by his appeasement of Khrushchev during the Cuban missile crisis. The same zealots were soured that Kennedy was mulling a retreat from Vietnam.

Garrison, who enjoyed the limelight, asserted that Oswald had never fired a shot. He condemned the Warren Commissions lone-gunman conclusion as totally false. He appeared on the Tonight show to discuss with Johnny Carson his allegations about an assassination team, shadowy figures on the Grassy Knoll, photographic evidence, and connivances involving Dallas police, the FBI, CIA, Secret Service and wealthy Texans.

But his showcase, the 1969 conspiracy trial of New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw, was a laugher, with bizarre testimony from oddball witnesses. A jury acquitted Shaw in less than an hour.

Nonetheless, some credit Garrison and the film J.F.K. for prompting Congress in 1992 to release nearly a million previously secret Government documents regarding Kennedy’s death.

The Government Super-Conspiracy

In this variation on Garrison/Stone, elements within the CIA wanted Kennedy punished for ordering a series of firings after the CIAs Bay of Pigs debacle. The CIA crew recruited trained assassins (Cubans, Mafia, Soviet spies, et al), then propped up Oswald to take the fall. The Secret Service and Dallas police were in on the planning, and the local cops helped trick Ruby into shooting Oswald. The killers were later killed, chopped to bits and buried in Mexico.

The truth was either (a) hidden from the law enforcement agency bosses or (b) revealed to the bosses, who hid the information from investigators to save a collapse of the entire American military-industrial complex.

Oswald and Other Undetermined Assassins

After a two-year investigation, the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1979 concluded that a second gunman also fired at Kennedy, based upon acoustical scientific evidence. The members wrote, The committee believes, on the basis of the evidence available to it, that President John F. Kennedy was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy. The committee is unable to identify the other gunman or the extent of the conspiracy.

However, it rejected as suspects on the basis of the evidence available the Soviet government, the Cuban government and anti-Castro Cuban exiles. It added that it could not preclude individual members of anti-Castro groups or the mob from involvement. And it flatly exonerated the Secret Service, the FBI and CIA.

JFK Assassination

The Search Goes On

Those obsessed with the Kennedy assassination tend to focus more on small clues. For conspiracy theorists, solving the case by identifying the perpetrators seems less likely than resolving some question about a piece of evidence.

Last fall, some of the leading figures among both doubters and believers gathered in Pittsburgh for a conference that marked the 40th anniversary of the event.

The Cyril Wecht Institute of Forensic Science and Law, associated with the Duquesne University School of Law, offered a national symposium with a full panel of scholars, scientists, and principals involved. The Crime Librarys Katherine Ramsland attended and filed the following report:

As thousands of mourners gathered to observe the ‘X’ on the road in Dallas where Kennedy was first struck down, and as Kennedy family members gathered at his graveside eternal flame in Arlington, Va., nearly 1,300 traveled the Duquesne auditorium to consider evidence for and against a conspiracy or cover-up.

In late 1963, about 52% of Americans believed that there had been more than one shooter. In 2003, that number stood at 75%, despite the efforts on the part of several government-sponsored committees to put the controversy to rest. In 1988, the Justice Department closed the investigation, stating it found no evidence of a conspiracy. To conspiracy theorists, that may only mean that the Justice Department is part of the cover-up.

From the opening evening through the three full days of presentations, the Pittsburgh program offered panels of writers with opposing views, pathologists and others with conflicting evidence, and legal experts offering rigorous debate.

Dr. Cyril Wecht started the program with a rousing call for truth, revelation, and accuracy in reporting. The 1960s-era media, he pointed out, was dramatically different from the media today, which would cover every minute aspect of the incident. In those days, Wecht charged, reporters and editors tended to accept what they were told.

Because of that, numerous young reporters in 1963 who obligingly described the lone-gunman scenario offered by government officials made their careers. In a shameful show of capitulation, they failed to get facts when they were fresh, and due to their lack of journalistic aggression, much has been lost that will never be recovered.

After Wecht spoke, a panel of often-contradictory authors presented their positions. It was clear that only a few speakers represented the government’s rendition of the story, as spelled out in the 1964 Warren Commission’s findings.

On this author’s panel, which included such notables as Anthony Summers and Walt Brown, debate was potent, and several speakers took pot shots taken at one panelist, Zachary Sklar, the JFK screenwriter.

Sklar, nervous at first, grew bolder when asserting that his screenplay was far more accurate than critics allowed. Yet even as he assured the audience that 80% of James Garrison’s moving speech was taken from court documents, news anchor Peter Jennings was closing an ABC special program that night with the words, “Jim Garrison never made this speech.”

Sklar insisted that the show’s researchers had never even bothered to check.

Which version is true? Sklar invited audience members to go to court records to see for themselves, but how many media researchers would actually do that? How many ordinary people would?

In other words, how often have undocumented rumors and unchecked information been passed from one source to another, like the child’s game of telephone, which at the end delivers output quite different from the original input? It could be difficult to discover whose documentation is credible, especially if those who passed on faulty information have had an agenda, such as a book to sell or a job even a career to maintain.

Such was the tenor of the conference: Each person who offered a presentation came prepared with those facts that supported his or her position and sometimes ignored or dismissed facts that did not. Skull fracture marks, recorded noises, crime simulations, and charts with complicated measurements were all presented from one hour to the next.

By the end of each day, it was difficult to know what to think. While each presenter did require time to lay out complex ideas, it might have been more effective to offer the key pieces of evidence and have two opposing theorists offer their explanations. That way, the audience could have considered the separate lines of reasoning side by side, rather than trying to recall earlier assertions that conflicted with present ones. It was difficult to keep track.

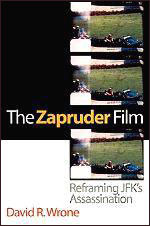

The second day began with a presentation of the evidentiary value of the famous Zapruder film, hailed at the conference as the single most important piece of evidence in the investigation.

The speakers included David Wrone, author of The Zapruder Film: Reframing JFKs Assassination.

He discussed the manner in which Zapruder had handled the film after the incident and dismissed ideas that government conspirators could have grabbed it before he sold it to Life magazine and somehow corrupted the footage to accord with the official theory.

Aside from technical impossibilities and the fact that the government did not then have the means to copy or corrupt the film in a way that would go undetected, the patriotic character of Zapruder and his family impeded such a theory. He had copied the film for the Secret Service and turned it over to Life.

The staff there laid it out, frame by frame, to process slides. Wrone says that slide No. 190 indicates that a bullet was fired from one side prior to the bullet that hit Kennedy in the neck, but it missed. In frame No. 224, the shot went through Kennedy. At the same time, the lapel flap on Connally’s jacket lifts, which “single bullet” theorists claim proves that same bullet went through Connally’s body.

However, it did not go through his lapel, but lower down through the body of the jacket. Wrone concluded that the inference based on the lapel movement, which could just as easily have lifted in a breeze, is incorrect. That seemed final, but he did not allow for the possibility that the flap could have moved in response to a bullet piercing the jacket below it. Wrone also contradicted later medical testimony by showing that the film frame of Kennedy lying against his wife indicates that a bullet struck the side of his head and not the back.

Eyewitness reports were discredited by several speakers, who described research in memory interference or showed how witnesses had contradicted themselves or changed their stories to align with official reports. Yet just because memory researchers have shown the existence of memory interference does not prove that these witnesses suffered from it, and none of the experts who made this claim took that final important step. They merely raised doubts.

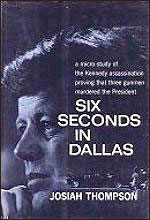

Speaker Josiah Thompson, a philosophy-professor-turned-private-investigator and author of Six Seconds in Dallas, said his report about the provenance of the bullet that was supposedly removed from Connally’s stretcher was a parable of the entire case.

“You pull any single thread, any single fact,” he said, “and you’re soon besieged with a tangle of subsidiary questions.”

He had attempted to learn just where the bullet, labeled Commission Exhibit 399, had been over the years and who had examined it. The stories from those who had handled it, however, including nurses, contradicted the possibility of ever learning its actual chain of custodyor whether CE 399 was indeed the bullet that had gone through Kennedy and into Connally. (This was later contradicted by another speaker who claimed that ballistics tests indicated that the bullet found on the stretcher was fired from Oswald’s rifle.)

Donald Thomas, an acoustic evidence specialist, said that the three-shot scenario did not add up. He presented evidence from sonar calculations and recordings from police motorcycle officers that in fact five separate shots had been fired. He said that committees who have studied this have known about the five separate gunshot noises recorded on the tape, but that they had dismissed one as a “false positive,” based on the fact that a single gun could not have fired two shots in such fast succession.

Thomas found this conclusion to be illogical, since it could just as easily be evidence to support two shooters involved. In 1977, forensic pathologist Michael Baden, who supported the findings of the Warren Commission, was put in charge of the forensic pathology investigation for the Congressional Select Committee on Assassinations. He recruited eight other esteemed medical examiners. They found a forensic disaster.

Baden contended that if the autopsy procedure had been done correctly, the many conspiracy theories would never have gotten off the ground. Yet as it turned out, Commander James Humes, the pathologist who performed the autopsy, had never worked on a gunshot wound.

He’d also been instructed not to perform a complete autopsy, but only to find the bullet, which was believed to be still lodged in the body. In his subsequent reports, his medical descriptions were nonexistent as he referred interested parties to the photos, which were unclear. Humes didn’t even turn Kennedy over to look at the wound in the back of his neck, or call the hospital in Dallas to learn that a tracheotomy had been performed, which went through the exit wound in the throat. He erroneously assumed the bullet had fallen out the same hole it had entered.

He also failed to shave the head wound to see it clearly, and photographed it through hair. After only two hours, he prepared the body for embalming and then burned his notes, recreating them later from memory. Baden’s team looked at crime scene and autopsy photographs, Kennedy’s clothing, autopsy reports, and X-rays.

It soon was clear that the examining pathologists had not known the difference between an exit and entrance wound. The team, with one exception, concluded that two bullets had struck Kennedy, and one of them had pierced him and wounded Connally.

The dissenting voice on this team was Dr. Wecht, the coroner of Allegheny County, who raised the alarm that something was amiss. He found that the “single-bullet theory” did not add up in terms of trajectory, weight and condition when found.

“The trajectory,” he said in a newspaper interview, “is a roller-coaster ride of vertical and horizontal movements and gyrations that obviously bullets in flight do not make. The bullet’s weight was just over 1.5% less than a store-bought bullet, despite fragments having been left in Governor Connally’s chest, right wrist, and left thigh.”

He also found the pristine and unmarked condition of the bullet to be highly unlikely after having made impact through skin, muscle, and bone. And he believed that the president’s head movement, as shown in the Zapruder film, was incompatible with a shot coming from behind. He thought the president had been struck twice in a synchronized fashion, from the rear and the right front side.

Indeed, in a 1972 story in The New York Times, Wecht had already raised the alarm about the missing brain and several missing X-rays and photos from the National Archives. “You put all these things together,” he says, “and you can better appreciate why there is so much continuing controversy today.” He believes that we will learn the truth one day, but perhaps not in his lifetime.

Senator Arlen Specter was also present to describe his part in the investigation after Kennedy died. He was junior counsel to the Warren Commission in 1964 and it was he who authored the “single bullet” theory. He spoke about interrogating Jack Ruby and offered insight into the man’s unstable character, but he did not acknowledge a direct challenge from Mark Lane, one of the early conspiracy theorists with his Rush to Judgment, who alleged that Specter had mishandled a witness and tried to blackmail her into changing her story.

Several authors who resist the conspiracy theories have offered the analysis that those who seek a dramatic and wide-reaching scenario simply cannot accept that a nobody like Oswald could take out a man of such international stature. Yet such a remark ignores the credibility and work of many of the scientists and scholars.

All the way from Ireland, Anthony Summers, author of Not in Your Lifetime, pleaded, “Don’t shrug off inconvenient facts with bland generalities or dismiss scholars as lunatics.”

Most of the people invited to speak have devoted years to the assassination and deserve respect at least for the important questions they have raised.

One could only leave this conference aware that much remains to be done, many of the facts are still unclear, and there seems to be no good reason why the government refuses to disclose all of the documents.

Web Sources

Marquette University Professor John McAdams has compiled a remarkable online archive of material on the Kennedy Assassination, with hundreds of links to both conspiracy theories and debunkers.

Books

Best Evidence: Disguise and Deception in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy, David S. Lifton, 1981

On the Trail of the Assassins: My Investigation and Prosecution of the Murder of President Kennedy, James Garrison, 1992

False Witness: The Real Story of Jim Garrison’s Investigation and Oliver Stone’s Film JFK, Patricia Lambert, 1999

Case Closed, Gerald Posner, 1995

Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy, Jim Marrs, 1989

High Treason: The Assassination of JFK & the Case for Conspiracy, Harrison Livingstone and Robert Groden, 1980 and 1996

Magazine

The Assassination Tapes, by Max Holland, The Atlantic Monthly, June 2004

Newspaper Article

Jim Garrison, 70, Theorist on Kennedy Death, Dies, by Bruce Lambert, New York Times, Oct. 22, 1992