RUTH ELLIS: THE LAST TO HANG — Prologue — Crime Library

To the living we owe our respect, to the dead we owe nothing but the truth. Voltaire.

Like all statistics, they serve a purpose of sorts. Like most statistics, they only hint at a deeper, unseen truth, hidden from view behind the dry, formal and dialectic structure of numbers.

She was 28 years old. Her height was five feet two inches and she weighed 103 pounds. She was well nourished and her body showed evidence of proper care and attention.

She was also very dead with a fracture-dislocation of the spine and a two-inch gap and transverse separation of the spinal cord. Just to make sure, there was also a fracture of both wings of the hyoid and the right wing of the thyroid cartilage. The larynx was also fractured.

She had died of injuries to the central nervous system, consequent to judicial hanging. She was a healthy subject at the time of her death. So said Doctor Keith Simpson, pathologist of 146 Harley Street and Guys Hospital. He was a reader in forensic medicine at London University, so he would know all about the statistics of death, especially as he had carried out the post-mortem examination on her, just one hour after she had been executed.

He knew nothing of the menage a trios that had brought her to the pathologist table. He could not know that her death would result in two people killing themselves and one dying of a broken heart. Or of the lawyer, so despairing of his faith in the law and the way it treated her that he would give up his career. Or the man who travelled half way around the world to escape from the certainty that he was partly to blame for her being here on this cold, metal table.

The small, slight cadaver stretched out before him was all that remained of a true tragedy of British justice. She was a statistic, one that would haunt the conscience of the British judiciary system for the next forty-five years.

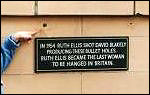

Ruth Ellis was the fifteenth, and the last woman hanged in England in the twentieth century. She was also the unluckiest. She did not kill for gain and, had the judge allowed her defense to be put to her jury, they may well have found her guilty only of manslaughter. She, however, never thought so. She never doubted in her own mind that she deserved to die for killing the man she loved.

Her death would be the final exclamation mark in a sad and tortured tale.

RUTH ELLIS: THE LAST TO HANG

We Always Hurt the One We Love

When you gaze into the Abyss, the Abyss gazes into you. Nietzsche

They drove north through the evening dusk, the city changing — grimy terraced streets of Camden Town and Holloway giving way to leafy suburbia. He swung left across Hampstead Lane and looped down through Spaniards Road, past Jack Straws Castle, cruising the narrow winding street into the village. He wheeled the big, black Ford Zodiac left into Pond Street and gunned it across the twists and turns into Massington Road and up to the house in Tanza Road. But when they got there, the Vauxhall Vanguard saloon was not parked in front of number 29.

The driver stopped his car, turned and looked at her. He was short and chunky with dark hair growing into a widows peak; hair sleeked back with cream. His eyebrows were prominent and he had a pencil-thin moustache, which stretched from corner to corner of a full, sensual mouth.

What now? he asked her.

She looked across the dimly lit road at the grim, Victorian building — bay windows, dusty red bricks and mock Corinthian pillars over the front door. She was so tired and drained of energy; her body and soul sucked dry by a force that had relentlessly dragged her to this ford that would take her across a river of no return.

Go down to the Magdala, she said, her voice soft, but strong.

He put the car into gear and drove up to Parliament Hill and turned left along the road towards the railway station, passing a couple walking down the hill, their bodies turned into the wind. One of them would soon become a participant in the tragedy that was about to unfold. The car went down the road into South Hill Park, a looped cul-de-sac on the edge of Hampstead Heath. The driver parked and switched off the engine.

They sat, staring across towards the four-story building. The Magdala Tavern was a favourite meeting spot for the people who lived in this part of Hampstead in North London. Although the marble and brick building was large and imposing, there were in fact, only two drinking areas. Through the main door fronting the street, you turned right into a snug, a smallish room with a feature fireplace, bench seats, tables and chairs, and to the left a door led into the main bar, a long narrow room, stretching about fifty feet, with the serving area immediately on the right.

He would be there, drinking with his friend Clive Gunnell. Although she did not know this yet for sure, she could see his dark green Vanguard, registration number OPH 615, parked outside the pub. It was nine oclock in the evening of Sunday, April 10th, and the Easter daylight had long vanished, making way for a murky, cold evening.

What are you going to do? he asked her.

She kept looking through the windscreen, across the dark street, into an even darker future that would carry nothing but pain and sadness. She knew that she was going to find her own private Calvary on this hill in Hampstead.

You know what Im going to do, she replied. Ive run out of options. This is all I have left. What else can I do?

She brushed a strand of bleached hair away from her brow and her fingers were trembling slightly. She was small and frail, her body concentrated like a tightly coiled spring. The sharp angles of her face, etched with a terrible sadness, were highlighted by the glow of the street lamps. He looked across at her, tiny in a green sweater, beneath a grey jacket and matching skirt.

Leaning across the seat, she kissed him on his left cheek. Thank you for It seemed as though she was lost for words, …being there when I needed you, and looking after me and Andy, and being patient and kind and everything The words tumbled out like dominoes spilling onto a card table. She opened her handbag and removed her black-rimmed spectacles from their case, slipping them on. Her eyesight was bad, but her narcissism was worse. She was too vain to wear them unless it was absolutely necessary, but she knew she needed to see clearly tonight of all nights.

He sat there, squat and solid, face blank and impassive, his thick fingers clutching the steering wheel. She touched his hand, and then opened the car door and started across the road, her black handbag bouncing on her hip, heavy with the gun.

He started the car and drove off into the night, a shadowy figure exiting stage left before the final act played out in all its tragic lines and shadows.

When she reached the building, she peered through the ripple glass window to the left of the main door. She watched him and Clive, with drinks, standing at the bar. He would be telling jokes, chatting up Mr Colson the landlord, maintaining an image; he was good at that. She saw them order three quart bottles of beer and some cigarettes before they would leave the bar, and exit onto the street. She moved back up the road a few feet and stepped into the dark cavity of the doorway of Hanshaws, the news agency next to the Magdala. Two young men were standing there, smoking, and talking to each other in low voices.

The two men in the bar said their goodbyes to their friends and left. As they came out onto the street, Clive walked around to the passenger door and, a bottle of beer under one arm, fumbled with his car keys. The car was parked inversely next to the curb, its hood facing down the hill instead of up

She stepped out of the shadows, starting down the hill, and shouted out his name — David!

The driver either did not hear her at first, or chose to ignore her, and carried on trying to unlock the car.

David! She shouted again, taking the revolver, a .38 Smith and Wesson, out of her bag and pointing it at him.

When he saw the gun, he did what he always did when faced with violence. He ran away — around the back of the car towards the protection of his friend Clive. As he drifted past her, she fired two shots. The noise was alien and shocking in this quiet London suburb. The man screamed out, Clive! His body jerking as the bullets tore into his body. His blood spurted onto the car panels, as she followed him around the automobile. Get out of my way Clive, she spat at the other horrified man caught in a landscape of terror. Her victim staggered and turned to run away, this time in front of the car and then up the hill, away from this terrifying source of danger. There was another shot and the man fell face down, left cheek pressing into the ground, his blood pumping over the pavement. She fired again, and then as she stepped up to the twitching body, she fired the fifth shot at point blank range. She held the gun three inches from his dark grey jacket and blasted into his left shoulder.

There was now a lot of blood everywhere: smeared across the car, flowing across the pavement, and especially on his clothing; it mixed with the beer spilling down the street in a small torrent from the quart bottle he had dropped. At least four of the five shots had found their target. Bullets had churned their way through flesh and tissue destroying intestines, liver, lung, aorta and windpipe. Massive shock and haemorrhaging had occurred.

She stood over his sprawled figure, and then lifted the gun to her head and pulled the trigger. The revolver seemed to have jammed. Slowly, as though in a trance, she lowered the gun, and stood for a second as if she was debating whether or not to fire the last round into the body at her feet. Instead she fired it into the paving stone. This time, the bullet ricocheted off the ground and struck the hand of a passer-by, a woman called Gladys Kensington Yule, aged 53, who was on her way with her husband to the Magdala for a quiet Sunday evening drink.

The Easter break had started badly for Mrs. Yule, a bankers wife. A son by her first marriage had committed suicide on the Good Friday, and she had decided that she needed a few stiff drinks to get her through the rest of the holiday weekend.

If she had tried, Ruth couldnt have picked a worse person to injure, even accidentally, in the whole of London. The bullet passed through the base of the womans thumb, fragmented, and smashed into the wall of the building, leaving scars that exist to this day.

The two young men, standing in the doorway of the news agency had witnessed the shooting. They later testified that they saw Ruth standing over David Blakely and heard two or three distinct clicks as she continued to pull the trigger on an empty gun.

As the echoing blasts of the gunfire died away, with the smell of cordite drifting around her, she turned, her body trembling and shaking, and said to Clive Gunnell, Go and call the police, Clive.

Inside the main bar, an off-duty Metropolitan police officer, PC 389 Alan Thompson, operating out of L Division, was having a drink while waiting for his girl friend to arrive. Someone rushed into the bar shouting, a blokes been shot outside!

PC Thompson put down his drink and walked outside. As calm as the Dead Sea, he walked up to the woman, now standing with her back to the wall of the tavern, who was clutching a revolver in both hands. Will you call the police? she whispered as he gently removed the gun from her shaking hands.

I am the police, he said as he stuffed the gun away in his pocket. She looked up, and her voice, soft and tremulous, said to him, Will you please arrest me? Thompson did, and gave her the first of three cautions she would receive that night.

She stood, leaning against the cold marble and brick of the building. Someone had given her a cigarette and she smoked away, looking down at the sad, and crumpled figure at her feet. On his outstretched hand she could make out his watch and signet ring, gleaming under the washed out lighting from inside the Magdala; his mouth was open and blood was leaching out. A man knelt beside him, lifting a limp arm, and felt his pulse. He looked up at the people gathering around, and said, Hes gone.

Clive Gunnell was screaming hysterically in the background, Why did you kill him? What good is he to you dead?

A man in the crowd said to Clive, Pull yourself together. Youre a man, arent you?

Ruth was mesmerised by the sight of the blood, so much of it; she had never seen so much blood in her life. Flowing out of David and mixing with the beer from the burst flagon, gurgling away down into the gutter. His life and all her dreams, gone together.

Within minutes, police cars, lights flashing and sirens blaring, arrived from Hampstead Police Station, which is less than a quarter of a mile to the west of the Magdala. An ambulance arrived and picked up the victim, who was accompanied by his friend Clive Gunnell. They were rushed to New End Hospital, where the injured man was pronounced dead on arrival.

Mrs. Yule, her hand spouting blood did not wait for help. In a state of panic, her husband hailed a passing taxi, whose driver only agreed to transport her to the hospital, provided she hung her blood-dripping right hand outside the window, so as not to blemish the interior of his vehicle. In a scene reminiscent of a Marx Brothers comedy, the cab disappeared into the night, the mutilated member leaving a trail of blood drifting and dripping onto the road behind it.

The small, blonde woman, surrounded by big and burly police officers, was taken to the police station on the corner of Rosslyn and Downshire Hill Roads, and by eleven oclock that evening had been identified as Ruth Ellis of 44 Egerton Gardens, Knightsbridge. She made a statement admitting shooting David Blakely. Three senior CID officers — Detective Superintendent Leonard Crawford, Detective Chief Inspector Leslie Davies and Detective Inspector Peter Gill, all of S division witnessed this at the Hampstead manor. As she gave her statement, she drank some coffee and smoked. At 12.30 pm on Easter Monday, April 11th, 1955, she was charged with murder. The next day, after a brief appearance at Hampstead magistrates court, she was removed to Holloway Prison in London, where she became Prisoner 9656 awaiting trial for murder.

She had 93 days left to live.

The misfortune of Ruth Ellis was not just that she killed a man. Neither was it the fact that his death resulted in her being hanged — the last woman ever by the British judicial system. The real tragedy of Ruth Ellis was that she died for love of a man who did not deserve it.

Life needs to be taken by the lapels and told:

‘I’m with you kid. Let’s go.’ Maya Angelou.

(Georgie Ellis)

Ruth was born on October 9, 1926, at 74 West Parade, a house in Rhyl, a seaside resort town on the northern coast of Wales. She was the third of six children to Arthur Hornby and his wife Elisaberta, who was also known as Bertha. Arthur was a talented musician. His wife, half French and half Belgian, had been raised by nuns and had fled Liege to seek safety when the Germans invaded her country during World War One. In a small boat she was brought to England, shoeless and wrapped in a blanket. With no qualifications or money, she had gone into service, until she met and married Arthur.

Ruth’s birth certificate showed her as Ruth Neilson, which was her father’s professional name. He travelled around the country seeking work, sometimes accompanied by his wife. There was little security in his chosen profession and he was often without a job. Their other daughter, Muriel, was regularly left to care for the rest of the family.

Ruth was myopic and had to wear glasses from an early age. She was an unremarkable child, pudgy and indistinguishable from the other children she socialised with. In those early days, there were no signs of the complex woman she would become, except even as an infant, she loved clothes and was very ambitious. Elisaberta would say of her daughter in later years, “She used to say to me, ‘Mum, I’m going to make something out of my life.'”

Perhaps she would, had she not had the misfortune to spend her short life surrounded by men who either were drunks, self-absorbed charlatans, physically abusive misfits, or combinations of all three.

(Georgie Ellis)

In 1933, Arthur Neilson found work with a band at Basingstoke in Hampshire and the family moved south. However, this position only lasted a few months and he was out of work until he found employment as a hall porter in a mental hospital. His musical career was over and his pride dented. He turned first to drink, and then to excessive drink. He became irascible and morose, taking out his failures and frustrations on his wife and daughters. Her father was the first of many drunken, desultory men who would come to haunt Ruth in the years ahead.

Eventually in 1939, Arthur’s job at the mental hospital went out of the window as visitors and hospital staff became more and more antagonised by his churlish attitude. This was the year that saw the beginning of World War Two and Arthur started another job, this time as a caretaker in Reading, west of London.

By 1941, Ruth had left school and found work as a waitress in a café. Later that year, Arthur moved on yet again, this time finding himself a better job as a chauffeur with a company based in Southwark, just over the River Thames from the City of London. The job came with a two bedroom flat, and Ruth jumped at the chance of moving in with her father. She found herself a job, first with a munitions factory and then a food processing company.

(George Ellis)

She was almost sixteen and had grown to her full height of five-feet-two inches. She was making the most of her face and figure, and now bleaching her dark hair with peroxide, a vane proclivity that would last for the rest of her short life. Her fixation with being a brassy blonde was at least partially responsible for the poor impression she made when giving evidence in her trial and in no small way contributed to her downfall in Number One Court at the Old Bailey.

She was also near sighted, but refused to wear glasses. And so pretty, gay and confident, she embarked on a mission to fill her leisure hours with fun and excitement. Her nights were spent at local dancehalls, cafes and drinking clubs. Even as German aircraft bombed London, she was enjoying life to the fullest during those turbulent years, taking for granted the food shortages, men in uniforms everywhere, the black-outs and the exciting uncertainty of life itself.

Whenever anyone tried to reproach her because of her behaviour, she would respond, “Why not? A short life and a gay one.” Her words were to prove ironically prophetic.

In March 1942, she became ill and was diagnosed with rheumatic fever. After two months in hospital, she was discharged, along with some medical advice that dancing would help strengthen her body and speed her recovery along. She threw herself into the dancing routine with great enthusiasm and, eventually as a result of this, found herself a job as a photographer’s assistant at the Lyceum Ballroom in the West End of London. There, at the age of seventeen, she met and fell in love with a French-Canadian soldier who was called Clare. After a brief affair, she became pregnant by him just after Christmas, 1944. Although he promised her the moon like most of the men who crossed her threshold, he delivered considerably less.

He was already married, with children back in Canada. One morning, a bunch of red roses and a letter were delivered to Ruth at 19 Farmers Road, Camberwell in South London, where she was living with her family. Clare was on his way back to Canada and she would never see him again.

Later in the year, Ruth travelled north to Gilsland, a pretty little village deep in the Northumbrian countryside. There, at a private nursing home, on September 15th, 1945, her child was born. A boy, he was christened Clare Andrea Neilson. Throughout his life he was always known as Andy.

Ruth returned to London and a mixed reception from her parents, but as usual, warmth and comfort from her elder sister, Muriel, who would act as a surrogate mother to the child in the years to come. Needing a job to support her son, Ruth applied for a position as a model at a Camera Club.

She was soon posing in the nude, while up to twenty men snapped away, expressing their artistic intellect, often through the lenses of empty cameras. After a busy day in the studio, some of these hot shot photographers would invite Ruth out for drinks, at one of the many clubs operating throughout the West End. In due course, at one of these clubs, she would meet a man who would nudge her a little closer to her final, fatal confrontation

As if there were some monster in his thought. Othello. William Shakespeare.

Morris Conley, known as Maury and sometimes as Morrie was a crook, plain and simple. When Ruth crossed his path for the first time, he was 44 years old and had already established himself a reputation as a fraud, a con man and a ponce. In 1936, he declared a business interest he owned, bankrupt, and as a result, made himself a profit of ten thousand pounds out of its failure, a considerable fortune in those days, when a new family home could be bought for five hundred pounds. Tried at the Old Bailey, in connection with this, he was found guilty of fraud and went off to prison for two years. He was also later arrested in connection with rigged slot machines he sold and operated. Inspector Bye of the Metropolitan Police said these slot machines were so crooked, the jackpot could never be won if played for a hundred years.

Through astute property deals, Conley came to own many houses and apartments, which were rented out to prostitutes. He also owned a number of nightclubs and drinking clubs in Londons West End. In 1956, Duncan Webb, a crusading crime reporter, named Conley as: Britains Biggest Vice Boss.

Conley was short, fat and ugly with tyre lips and heavy jowls. Some one once described him as being ugly as a toad. He was however, affable, shrewd and very rich. While he came across as a smooth, jolly, middle-aged nightclub king, and something of a social butterfly, Webb has also described him as, a monster with the Mayfair touch.

Sometime in 1944, Ruth and Conley came together. She met him at one of his enterprises, the Court Club at 58 Duke Street, just off Grosvenor Square. They sat drinking through the early evening and talking quietly across a table at the back of the club. Ruth remembered that she was flattered and impressed by this wealthy and successful club owner. He, in turn, recognized in Ruth, the perfect formula for a good club hostess — attractive with a vibrant personality and a core of disenchantment that would allow her to operate above her emotions.

Ruth joined the other six hostesses who supplied the feminine charms at the club in return for a weekly wage far in excess of the average at that time, plus perks such as a clothing allowance, free drinks and, above all for Ruth, the chance to mix with a good class of people.

She and Conley formed an alliance that would last for nine years. She would become one of his best managers, operating a number of his clubs across the West End. In return, he would use her for sexual favors and, in addition, abuse her when he was drunk. It was a scenario that would be replicated with boring repetition through her life, as over and over again, she chose the wrong man for the wrong reason.

Along with Conley, Ruth would also make herself available to some of the clubs clients, and was soon establishing a reputation with men of substance and high social standing, the two attributes that Ruth had yearned for all her short life. The money she earned seemed to evaporate on living the good life, but she also helped support her parents and made sure her son was well cared for. More and more, her sister Muriel was mothering Andy, with Ruth struggling to find time on Sundays to share with the child.

Early in 1950, Ruth became pregnant by one of her regular customers. She had an abortion by the third month and returned to work almost immediately. Under the stress of maintaining a bright and bubbly image for her clients, she was drinking heavily and punishing herself physically to remain the ever-gay companion her customers expected. It was during this time, the summer of 1950, she met up with the next man who was to have a major influence on her life. In keeping with the pattern she was establishing, he would turn out to be less than perfect.

|

The lunatic, the lover and the poet William Shakespeare.

George Ellis

George Johnson Ellis was born on October 2nd, 1909 in Manchester, in the north of England. He and his brother Ted, both trained to become dentists. George was also a gifted piano player, who could perform at will, playing almost any tune by ear. He married, and he and his wife, Vera, had two sons. Their marriage was, however, an unhappy affair; his frequent drinking bouts and violent temper eventually drove his wife away. He returned home one day to his house in Sanderstead, Surrey, to find Vera had cleaned it out and left with her children and all the household furnishings. |

|

George spent ever-increasing amounts of his time frequenting bars and drinking clubs in London and one day at the Court Club, he met up with Ruth. She had heard about him from some of the other hostesses, who referred to him as the mad dentist. He spent money lavishly, and spun wild tales about himself and his exploits. One night in June 1950, Ellis was pestering Ruth to spend the evening with him. She and another club hostess had planned to go out partying that night with a good looking American Army sergeant called Hank, and so to get rid of Ellis, she agreed to meet up with him later that night at the Hollywood, another club owned by Conley. She never kept the appointment and the next day discovered that George had been attacked outside the Hollywood. He had been making a fool of himself with a woman, who turned out to be with a group of East End villains. One of them, a thug from Bethnal Green, attacked George and slashed his face with a razor. He was rushed to St. Marys Hospital in Paddington for emergency surgery. When he eventually turned up at the Court Club, his face stitched up, wearing dark glasses and a hangdog expression on his face, Ruth was overcome with remorse for tricking Ellis into going to the Hollywood. She agreed to go out for dinner with him. They were chauffeur driven to Georges golf club at Purley Downs, and after a long nights wining and dining, Ruth woke up in bed at the Ellis house in Sanderstead. It was the start of a whirlwind courtship, as George took Ruth under his wing. They ate and drank at the best places and he showered her with gifts. She slowly came under his spell, seeing him from a different perspective. He was intelligent, musical, held a private pilots licence (a rare achievement at this time), and was warm and humorous. At least, as long as he was not sinking back the gin and tonics. Then he was quite different. Perhaps if she could wean him off his alcoholic dependency, he might just be the man to satisfy her yearning for respectability and security. Andy was now six years old, living between his grandparents in Brixton and his Aunt Muriel. He needed stability in his young life and Ruth was going to try hard to find it for him and herself. She and George went off on holiday for three months to Cornwall, and when they returned to London, they moved into the Sanderstead property. George, however, was still hitting the bottle in a big way and, after many noisy fights, he agreed to admit himself into Warlingham Park Hospital in Surrey to be treated for alcoholism. After his release, he and Ruth decided to get married and on November 8th, 1950, they did at the Registry Office in Tonbridge, Kent. George found work with a dental practice in Southampton on the Hampshire coast and they moved south early in 1951, taking up residence in a village called Warash. However, the cure George had taken at Warlingham, proved as transient as his other attempts at kicking his habit, and after a few weeks on the wagon he was a regular at the local pub, often drinking himself insensible. Soon, he and Ruth were fighting again at home and in public. After one bitter and brutal confrontation, Ruth packed her bags and went home to her parents. Predictably, after only two days, she returned to George. Their love-hate relationship continued, but now there was a new ingredient added. Ruth became obsessed with jealousy, believing that George was not only drinking, but also womanising. During one particularly mean and acrimonious confrontation, he beat her badly. She continued to leave and return, but things were not getting any better. The police were now being called out to deal with them. On one occasion, George kicked in the front door of their house after Ruth had locked him out. Their verbal abuse of each other reached a peak when she called him a drunken old has-been from a lunatic asylum and George, in return, dubbed her a bloody bitch from Brixton. In May 1951, George was fired from the dental practice. Morgan, the owner, had suffered him long enough. Ruth and her husband travelled to Wales to stay awhile with his mother. In due course, George found work at another dental practice in Cornwall and travelled down there, while Ruth, yet again, went home to stay with her parents. She had discovered she was pregnant, and so tried again to reconcile with her husband. She went to stay with him in Torquay where he was working, but their time together was, as usual, filled with bitterness and stormy, drink-fuelled scenes. Finally in May, George re-admitted himself into the hospital for further detoxification treatment.

Dr. T. P. Rees

Ruth visited him here frequently, but again, developed a phobia that George was having improper relationships with the staff and female patients. On one occasion, she became so inflamed, ranting and raving and screaming in coarse, uncouth language, she had to be forcibly restrained and sedated. Dr Rees, a psychiatrist who was looking after George, prescribed drugs for Ruth and from that point on until the day she killed David Blakley, she was under his care. It has always remained a mystery why her defence counsel at her trial did not call him to give evidence of her state of mind, and that fact that the legally prescribed sedatives, combined with alcohol, could have made her incapable of rational behaviour at the time she fired the fatal shots. |

|

On October 2nd, 1951 at Dulwich Hospital, London, Ruth gave birth to a 7lb girl, who would be called Georgina. The fathers address on the birth certificate was shown as 7, Herne Hill Road, Lambeth, London, SE 24. This was the home of Ruths parents. George was in fact still in residence in the hospital at Warlingham. He checked out of here after the baby was born and moved north to settle in Warrington, Lancashire. Here, he found himself a job as a schools dental officer with the local Health Authority. Less than a year after their marriage, he filed a petition for divorce on the grounds of cruelty. Ruth was now twenty-five years old and had two children to support. She was no better off financially than she had been almost ten years ago when she had started work as a waitress in Reading. In urgent need to find some way to generate income, she turned to Maurie Conley. He welcomed her back with open arms and Ruth was soon operating in her old environment. She was back at the Court Club, only now it was known as Carolls. There were at least three more men to enter her life and have a profound impact on her. One of them would pay dearly for his association with Ruth Ellis. |

RUTH ELLIS: THE LAST TO HANG

The Sponger and the Ponce

Only enemies speak the truth; friends and lovers lie endlessly, caught in the web of duty.

Stephen King.

Moving back into the shady world of Conley, Ruth began hostessing for him at Carrolls. Now, refurbished with a restaurant, cabaret and dancing, it stayed open until 3 am. Ruth became a favourite again with the regulars, and soon developed a wide circle of friends. There was a banker from Persia, an oil tycoon from Canada and a businessman from Switzerland who always sent notes to her signed, always, your naughty Norbet. Conley arranged for Ruth to move into one of his properties — Flat 4, Gilbert Court, Oxford Street, a block of apartments owned by his wife, Hannah.

In December 1952, Ruth became ill and in due course, specialists discovered she had developed an ectopic pregnancy. She was operated on and hospitalised for two weeks, early in 1953. By April, she had returned to work with her associates, Vicky, Betty, Michele, Cathy, Jacqueline and Kitty. The summer and autumn of that year was a good period financially for Ruth. She returned from a holiday with one client who gave her a cheque for four hundred pounds for services rendered.

Business was good at Carrolls mainly because of her boundless enthusiasm and effervescent personality. Ruth had a knack of making her customers relaxed, happy and most important, loose with their money. She is photographed at the Club, surrounded by smarmy, lecherous men, smirking into the camera, looking sexually expectant. She catered to the needs of her patrons, and on occasions would hand out small printed cards that read:

Why women over 40 are preferred.

THEY DONT YELL!

THEY DONT TELL!

THEY DONT SWELL!

And they are as

GRATEFUL AS HELL!

As the long, hot summer of 53 developed, Ruth was herself developing a group of new friends who were lot more interesting than the paunchy businessmen and manufacturers who she normally socialised and occasionally slept with. They were a group of young, noisy, exuberant thoroughbreds, which raced cars for a living. Led by Mike Hawthorne — a twenty-three-year-old, six feet two inch tall, blonde Adonis type — this group based themselves at the Steering Wheel Club, located across the road from the Hyde Park Hotel.

Hawthorne drove for the Ferrari racing team and his fellow driving enthusiasts included Sterling Moss, Peter Collins, Roy Salvadori and the Italian up-and-coming ace, Alberto Ascari. They would drift into Carrolls late in the afternoon along with the groupies and wannabes, to drink and socialise. Sometime towards the end of 1953, possibly in September, a young man wandered into the club to drink with this group. Ruths first impressions of him very not very favourable:

He strolled in wearing an old coat and flannel trousers. He greeted the other lads in a condescending manner…I thought he was too hoity-toity by far.

Soon, he was antagonising Ruth, who on this particular day was not there to work, but was simply enjoying a drink with some of her friends. His sarcastic, pithy comments about the club and the staff soon had her riled up. She turned to one of her companions and in a loud voice said, Who is that pompous little ass?

David Blakely stood five feet nine inches tall and weighed about 154 pounds. He had deep brown eyes, and long, almost silky eyelashes. His face was lean and his thick, dark hair was brushed back from his forehead. In his photographs, he looks exactly what he was: the product of a public school education and the result of a wealthy middle-to-upper class background. He had enjoyed an indifferent school career, his only interest being racing cars. He left Shrewsbury School blessed with the classic public school aura of self-confidence , but with no power of analysis or debate, being weak and rudderless when engaged in serious conversation. He was a child of a broken marriage and most of his life he had been spoiled by his parents.

It seems hard to comprehend why Ruth Ellis would even contemplate having a drink with a man like this, let alone falling hopelessly in love with him. But this is, in fact, exactly what she did. It is possible that all of her life, she was a woman who yearned for more than just love. She appears to have lusted after the respectability of romance and was drawn time after time, into affairs that were, in reality, the passions of her partners infidelities. A woman of unstable temperament, she became a victim of her insatiable yearning for happiness at any price.

She would find it only in fleeting moments with this man, who would come to cause her more heartbreak than probably all the other men in her life combined. All he would offer her was endless miles of travel down a bad road.

Sometime in October, Conley offered Ruth the job as manager of a club he owned called the Little Club. It was situated at 27 Brompton Road in Knightsbridge. As the name implied, it was too small to have Conleys usual complement of a manager, directing anywhere from ten to twenty hostesses. Ruth would have a staff of just three to embellish its flocked wallpaper rooms and little gilt electric candelabra mirrors. A two-bedroom flat above the club went with the job and it was rent-free. She moved in here along with Andy. Her daughter was at this time being cared for by her sister, Muriel. To Ruth it must have seemed like heaven. It was in the posh West End, close to Mayfair and Belgravia, and it was her club.

Ruth later claimed that the first person she ever served here was David Blakely, who was already a member when she assumed the managers position. She remembered that he looked surprised and nervous when they came face to face and he recognised her as the platinum blonde he had verbally scrapped with at Carrolls. What triggered their attraction to each other will never be known. Sometimes you dont have to look at or even relate to another person. The lightning strikes, and that is it. Their allure for each other may well have been hammered out on an anvil of lust. Both of them were victims at different times of each others carnal desires. They would be sleeping together within two weeks and nineteen months later he would die in a pool of blood, as she stood over him with a smoking gun in her hand.

Who was David Blakely?

Ruths daughter, Georgina, referred to him as: a sponger and a ponce, who would feed his drinking habit at anothers expense. Another writer referred to his basic lack of masculinity.

Cliff Davis, a racing car driver, saw a lot of David. He said of him, He liked his boozehe wasnt averse to poncing it, and he certainly ponced off RuthDavid was a good-looking, supercilious shit, but you couldnt help liking him. I knew he used to knock her aroundtheirs was a love-hate relationship, as unstable as a stick of dynamite. Ruth, in her evidence in court, said of Blakely, He was very persistent and jealous.

David Moffatt Drummond Blakely was born in Oakland, a private nursing home in Sheffield on June 17th, 1929. He was the youngest of three sons and a daughter, the family of Dr. John and Annie Blakely. When David was five, his father was arrested and charged with the murder of Phyllis Staton, 25, an unemployed waitress. It seemed that they had been having an affair and she had become pregnant. The doctor had illegally prescribed drugs to abort the pregnancy and the young woman died suddenly of septicaemia. After a brief hearing, in February 1934, the Sheffield magistrates dismissed the charges. They felt the case was too weak to prosecute, and it appears that Davids father carried on his medical practice, unaffected by all the adverse publicity.

Why she waited so long is hard to fathom, but on May 24th, 1940, Mrs. Blakely was granted a divorce and remarried in 1941. Her new husband was Humphrey Wyndham Cook, a successful businessman and one of Britains best-known racing car drivers. Davids mother moved to London along with her four children.

David was sent off to boarding school at a small, second division public school in Shrewsbury, a town near the borders of North Wales. He was an average to low achiever there, his only real interest being racing cars. After leaving school and serving two years doing his mandatory National Service in the British Army, he found work, through his stepfathers influence, as a management trainee at the very fashionable Hyde Park Hotel in London. He had little interest in this job however and would swan off at every opportunity to spend his time and money with the men he most respected and admired — racing car drivers.

Like so many men who were educated at private boarding schools, David Blakely enjoyed schoolboy horseplay, squirting people with soda fountains or putting ice-cubes down their necks. He did this once with Mike Hawthorne, who chased David around the Steering Wheel Club, threatening to thrash him. David was basically a whinging coward, who would hide behind furniture or womens skirts to escape the fights he provoked. Some of the drivers enjoyed his boyish high spirits, others despised him.

His salary was augmented by donations from his stepfather and an allowance from his mother. He was able to scrape up enough money to maintain a second-hand sports car, bought for him by his stepfather as a twenty-first birthday present. He entered it in races, which gave him some experience, but no victories.

(Syndication International)

In February 1952, his father died suddenly, and in due course, David received seven thousand pounds as his share of his fathers estate. He had also by this time met and formed a relationship with a regular visitor to the Hyde Park Hotel, a Miss Linda Dawson, the daughter of a wealthy manufacturer from Huddersfield in Yorkshire. This did not stop David from sleeping around with other women however. At one time he was having an affair with an American model, going out with a theatre usherette, having another affair with a married woman as well as spending time with Miss Dawson. His sense of morality was loose and his commitment to anyone was tenuous to say the least.

In October 1952, the hotel finally gave up and sacked him after he had a particularly violent row with the banqueting manager. As compensation for this interruption to his life, his mother took him away with her on a world cruise. When they returned, he joined a manufacturing company in Penn, Buckinghamshire, called Silicone Pistons. Although he had access to a flat attached to the new family home nearby, he spent most of his time in London, staying at his stepfathers London address, 28 Culross Street, which runs west from behind the American Embassy on Grosvenor Square to Park Lane.

A month after Blakely and Ruth met, he became engaged to Linda Dawson. On November 11th, 1953, an announcement appeared in the London Times.

So here was Ruth Ellis, still officially married to George and David Blakely now officially engaged to Linda, sharing a bed in the two-room flat, with son Andy and daughter Georgina, taking up some of the small space that was available. David would stay overnight through the week and then go and stay with his parents in Penn for the weekend. He would have had no patience with the children, and Ruth must have found her time management squeezed thin between the demands of her managers job, her childrens needs and the sexually demanding tantrums of a man not renowned for equanimity and understanding.

Then just to compound and confuse matters, there was the other man who came into her life.

There are three things men can do with women: love them, suffer for them, and turn them into literature.

Stephen Stills.

Of all the characters that populate this story, Desmond Cussen is perhaps the most enigmatic.

He was referred to at the trial of Ruth Ellis as “her alternative lover,” but he operated at a deeper level than just as a sexual or romantic foil for this woman who was using him as leverage in her passionate play for David Blakely.

Some people get lost in thought because it is unfamiliar territory; Ruth Ellis wandered through a hinterland of emotional confusion, torn between her desire for a young, vibrant Lothario, and the comfort and security of an older man who would ultimately fulfil the role of her paternal guardian.

Ruth claimed that she started an affair with Cussen on Thursday June 17th, 1954. It was to her, an act of spite against David, who had not returned to her from racing at Le Mans in France.

(Syndication International)

Desmond Edward Cussen was thirty-two when he first met up with Ruth. He was born in 1921 in Surrey and had been an RAF pilot, trained in South Africa, and flying Lancaster bombers during World War Two. After he came out of the service in 1946, he studied for and became an accountant.

In due course, he was appointed a director of the family business — Cussens & Co., a wholesale and retail tobacconists with outlets in London and South Wales. He was based at the company’s head office at 93 Peckham High Street in south London. He lived in a self-contained flat at 20 Goodward Court, Devonshire Street in the fashionable Marylebone district, north of Oxford Street.

A car enthusiast, although he never raced professionally, he drove around town as though he was qualifying for a grand-prix event. He was apparently a shy man, dominated by his mother, a trait he shared with Blakely, and outside of work, had found entertainment and companionship at the Steering Wheel Club. He was described as; “‘a solitary man, always polite, who never used foul language and did not belong in the circles in which he moved.” Cliff Davis had little time for him, saying, “The real villain of the piece was Desmond Cussen. He was a sneaky bastard.”

Cussen had met Ruth at Carroll’s before David Blakely came into her life and was connected to David through their shared fondness for motor racing and the Steering Wheel Club. There seems little doubt that he and David disliked each other, even before Ruth came between them.

Cussen, it appears, fell desperately in love with Ruth. He adored her energy, her style, her wit and her self-possession. The way she handled the guests at the club and traded profanities with them; her ability to keep up with their raunchy and profane bawdiness. As Cussen loved her and watched her, the more she became attracted to another man, one he disliked. The miasma of jealousy was fuelled by David’s laid back, casual and supremely confident “in-your-face” approach.

Desmond Cussen must have realised how ill prepared he was to compete with a man who was not only almost ten years younger, slim, handsome, with a relaxed, buccaneer attitude to life, but was also so obviously the complete antithesis of what he himself was, a man once described by a former colleague as “a bit of a drip.”

By the spring of 1954, events were starting to develop their own momentum. George, Ruth’s husband, had reappeared on the scene and was stopping in at the Little Club from time to time. He and Ruth were trying to manoeuvre themselves around a number of their problems. He wanted their divorce to become final; she was fighting it off, in order to hang on to the maintenance he was paying. More pressing was the problem of their young daughter Georgina, who was now three. Ruth’s life style and living quarters were not an ideal environment for a small child. It was finally agreed that George would take her back to Warrington and arrange for the child to be adopted. This happened in May 1954.

(Syndication International)

Earlier, in April, Ruth had met up with Carole Findlater for the first time. She and David had attended the thirty-third birthday party of Carole’s husband, Anthony. Anthony “Ant” Findlater was the third and final man, who along with his wife, would help connect up the dots that would disclose the shape of the matrix spawning the events of the next twelve months.

True friends stab you in the front.

Oscar Wilde.

Anthony and Carole Findlater lived at number 29 Tanza Road, Hampstead. They had a second floor flat in this tree-lined street that backed onto the southern edge of Parliament Hill, next to the famous Hampstead Heath. Today, Hampstead is one of the most prestigious and expensive suburbs in London. Forty-five years ago it was a modest outpost of suburbia, where strangely enough, the second last woman to hang in England, Mrs. Styllous Christofi, had committed murder — killing Hella, her daughter-in-law in 1954.

Anthony, always known as Ant, was from a wealthy Dublin family. His father, a prosperous businessman, was one of the better pre-war racing car drivers and a successful motorcar engine designer. Ant went to Hurstpierpoint Public School and then studied automobile engineering until the outbreak of the war in 1939. He met his wife Carole Sonin, the daughter of a relatively comfortable Jewish manufacturers agent, when they were both serving in the Royal Air Force.

After the war ended, they married. Carole worked as a journalist and Ant found a number of poorly paid jobs with engineering companies. They were living in a flat at Number 52, Colet Gardens in Hammersmith, west London, when Ant and Blakely first crossed paths. Ant was trying to sell off an old Alfa-Romeo sports car. David and a friend had come along to look it over. This was early in 1951.

Soon, David, Carole and Ant were an item. Davids pride and joy at this time was an HRG sports car, named after the designer H.R. Godfrey, the one his stepfather had bought him for his twenty-first birthday. The two men agreed to share the cost of racing the car. David also had an ulterior motive for keeping the relationship on the boil. He already had the hots for Carole.

David and Carole would meet some evenings at the Trevor Arms, a pub in Knightsbridge; Carole explaining her late nights to Ant, as part of her duties attending the National Union of Journalists. By the autumn, David was pleading with Carole to elope with him. Just what the attraction was is hard to fathom. Perhaps it was the age difference; she was twenty-seven, he was twenty-one. He seemed to have always favoured women older than himself, particularly in serious relationship situations. She was certainly out of his league, being described by a fellow journalist as a powerhouse of ambition and energy.

One day, after work, Carole went home to pack her bags and leave. But when Ant pleaded with her to stay, her fine sense of Jewish home won her over, and she agreed to stay on. The marriage, however, was doomed to failure, and eighteen months after Ruth gunned down David Blakely, the couple divorced.

When Carole told David she was not leaving her husband, he asked if she had told Ant who her lover was. Carole said, Yes, but that doesnt make any difference, does it? To which the romantic Blakely responded in muted rage, You stupid bitch, now look what youve done. Who the bloody hell will tune my car now?

Blakely may have been a drunk; he may have been a woman beater; he may have been an arrogant up-himself mellifluous womanising narcissist, but he was quite clearly a realist in the things that he considered important. Somehow, his association with the Findlaters survived and three years later they appeared to be the best of friends.

Ruth always suspected the Findlaters and, in particular Carole, of exerting a domineering influence over David and of turning him against her towards the last few days of their relationship. She became certain that Carole and Ant conspired to persuade David to desert her in that fateful and final week leading up to Easter, 1955.

By the April of 1954, Ruth had already met Ant Findlater when David brought him into the Little Club for a drink. When Carole organised a birthday party for her husband, she personally telephoned Ruth and invited her along. Carole was no doubt curious about Davids latest mistress and wanted to check her out for herself. She wasnt that impressed and recalled later, She was wearing a black dress with a plunging neckline; she had a small bust, small wrists and ankles, the effect was shrimp like. Ruth said Hello to Carole and then ignored her for the rest of the evening.

Ruth was as equally unimpressed with Carole, remembering, Carole behaved like the Mother Superior herself, but I took no notice.

In June, David went to France to drive in the famous Le Mans 24-hour race, not returning until the middle of July. Although he sent Ruth two postcards, expressing his love, Ruth became jealous and, in a fit of temper or perhaps just a mood of alcoholic abandonment, entered into a sexual affair with Cussen. She claimed at her trial that she had hoped Cussen would tell Blakely and that this would finish Davids longing for her. If that was the truth, it didnt work.

After David returned from Europe, Ruth had yet again changed directions, tacking from a wind of rejection back into one of acceptance. She decided to throw him a belated birthday party — he had been abroad on 17th June, his twenty-fifth birthday. David arrived late for his own birthday bash, explaining to Ruth that he had been across the road at the Hyde Park Hotel, breaking off his engagement with Linda Dawson. He asked Ruth to marry him and as a result, Ruth decided to no longer fight the divorce proceedings with her husband George.

In August, David raced in Holland at Zandvoort an MG car owned by one of his friends, and invited Ruth along. In one of her rare moments of disciplined responsibility, Ruth turned down the invitation. She had, among other things, to make a decision about Andy and his education. In due course, her son, now ten years of age, went off to boarding school in September, his fees and school uniform paid for by Desmond Cussen.

David had been occupying his spare time for many months trying to build a racing car, which he had called The Emperor, using Ant Findlater as his chief mechanic. It was a time consuming and costly exercise and was eating away at Davids rapidly dwindling legacy. He was drinking heavily and Ruth was supporting him financially; his income from his job at the piston factory and the money his mother allowed him each week was hardly covering his expenses.

Pleading poverty, he persuaded Ruth to allow him to move in with her; also, she started allowing him to run up a slate at the Little Club. They were both drinking heavily by this time. Ruth, who was basically a gin and tonic and champagne type, started using Pernod, a potent French aperitif made from the wormwood plant, which was being stocked so that customers could buy it for the French barmaid, Jackie Dyer. Often known as lunatic soup for its strength and power of intoxication, Pernod may well have contributed to her unstable condition the night she went after David with a .38 Smith and Wesson.

In October, Ruth hosted herself a birthday party at the club. She was twenty-eight. David sent her a greetings telegraph from Penn, and a cheap, flowery birthday card on which he had scrawled in his childish handwriting: Happy birthday Darling, BE GOOD. He promised her a trip to Paris, but lied his way out of this. They were both becoming jealous of each other. Ruth had found out about his earlier affair with Carole Findlater and warned him off visiting her at Tanza Road, and David was becoming increasingly suspicious and resentful of Ruths socialising in the club. More frequently their arguments were climaxing in violence and he was beating Ruth on a regular basis.

Ruth later said in evidence, He was violent on occasions…always because of jealousy in the barhe only used to hit me with his fists and hands, but I bruise easily, and I was full of bruises on many occasions.

As the year drew to a close, Ruth was faced with some serious decision-making. The takings at the club were dropping and Conley was pressuring her to do something about it. She had allowed David to run up an enormous bar tab, which he could never meet, and she had also been spending a lot of time away from the business, catering to Davids whims. He loved trawling through the clubs and pubs of the West End. One of his favourite drinking places being Esmeraldas Barn, which would become notorious a few years later, when it was taken over by the infamous Kray twins. By the end of the year, takings at the club had fallen from over two hundred pounds a week to under eighty. In December, Ruth quit the Little Club. She either resigned or Conley sacked her; either way, she was out of work.

She needed somewhere to live and also to care for Andy when he returned from his boarding school for the Christmas break. The faithful Desmond was her solution and she moved into his spacious flat at Goodwood Court.

Christmas was approaching and events would start to unfold with increased velocity.

Its a late day for regrets.

Eugene ONeil

Although David was livid at the thought of Ruth moving in with Desmond, she placated him by pointing out that at least she was breaking away from club life, the first step to a level of respectability — something David had wanted her to do for months. She assured him that she would not sleep with Cussen, and between the 17th of December and February 5th, 1955, she and David stayed off and on at the Rodney Hotel in Kensington, registering as Mr and Mrs Blakely. To Desmond, she explained her nights away by saying she was visiting either girl friends or her daughter, Georgina, up north.

That Christmas, Ruth gave Desmond and David identical silver cigarette cases as presents. On December 25th, Ruth hosted a party at Cussens flat. Cussen was at a business party and did not arrive back at his flat until later in the evening. By then, David had turned up and he and Ruth had another furious row over Ruth leaving her son asleep in the flat while she and her guests had gone out clubbing. David railed at Ruth for being a tart and sleeping with Cussen; she in turn accused him of still having an affair with Carole Findlater.

Later that night, drunk as coots, they both made their way to Tanza Road, where in fact they found the Findlaters had gone off for the Christmas break to stay with friends at Brighton, and eventually Ruth and David collapsed drunk and exhausted in bed to sleep off their hangovers. Cussen, worried about Davids level of inebriation, had followed them across London. However, the patron saint of drunks had watched over them and David had somehow negotiated the journey without mishap. Cussen sat in his car, watching the house until it was almost nine in the evening. Then with a heavy heart he returned to Goodwood Court to look after Andy and the guests who were waiting for their hostess to return.

The next day, December 26th, Ruth returned to Desmond, explaining her night away by saying David had threatened to commit suicide and that was why she had been forced to spend the night with him.

David spent the day at the Brands Hatch racing circuit, driving The Emperor in its first race, The Kent Cup, and coming a respectable second. Early in the New Year, Ruth became suspicious that David was having another affair, this time in Penn, and had Cussen drive her across London to the dormitory suburb. There, she saw David leaving the home of a married woman, whose husband was away on a business trip. She was of course, older than David and very good-looking. It can be imagined just how this stirred up the anger and jealousy in Ruth. On the 8th of January, while staying at the Rodney Hotel, they became involved in another blazing row, brought to a head by Davids relationship with this other woman. He left for Penn, and when he had not contacted Ruth by January 10th, she sent him a telegram, which read:

Havent you got the guts to say goodbye to my face Ruth?

David got himself into a funk over this. Firstly he was concerned that the news would get around and create a local scandal. Then the fact that he was spending so much of his time courting this other woman might impact on his job. He was also terrified that Ruth might get some of her gangster friends to pay him a visit. Ruth had brought up this possibility on more than one occasion. Her job with Connelys clubs had brought her into touch with many London villains. He poured out all of his fear to Ant Findlater, telling him that he just wanted to get away from Ruth and never see her again.

However, repeating the same steps that had driven their actions throughout their relationship, by the 14th of January, they were back together in the Rodney Hotel. On the same day, Ruth got her divorce from George. It would be absolute in six weeks and there was now nothing to stop them marrying.

David must have surely felt he was being backed into a corner from which there was no escape. However, their untenable pattern of quarrelling and passionate reconciliations continued, requiring the help of friends to help them patch up their differences. Ruth had Cussen drive her around so she could spy on David, and at the same time Cussen was checking on them. He knew by now that they were meeting at the Rodney, but seems to have been so infatuated with Ruth that he went along with their liaison.

On February 6th, there was a major bust up in Cussens flat. Desmond was away at the time. David claimed Ruth tried to stab him and called his friends, Clive Gunnell and Ant, to the rescue. When the men arrived, they found Ruth with a black eye, covered in bruises and limping. David also had a black eye and was also limping. It must have been a whopper of a scrap. She had taken Davids car keys and would not let him go, at one time sitting in his car to prevent him leaving, and then lying in the road in front of Gunnells car, to prevent them escaping that way. Eventually, when she had exhausted all of her energy, and sobered up, the three men drove off and Ruth returned to Cussens flat.

Over the next twenty-four hours, Ruth had Desmond drive her around while she tried to track down David. They went to the Findlaters flat in Hampstead and then followed him down to the Magdala pub, a favourite drinking spot for David and his friends. They drove over to an address near Euston Station, trying to trace another woman David had mentioned to Ruth in one of their drunken brawls, and then to Penn, where Desmond confronted David, whose car they saw parked outside a pub in Gerrards Cross. Faced with the strong likelihood of a beating by Desmond, David retreated, colours flying, and headed back to London.

That afternoon, Ruth received a bunch of red carnations with a card that said, Sorry darling, I love you, David. Its hard to know whether the flowers came as an emissary of love or fear.

They met up later that night. David explained his violence was because of his frustration over Ruth sharing accommodation with Desmond. Ruth convinced David they should move into their own flat, saying she could borrow the rent money from a friend. The friend of course, turned out to be Desmond, the ever-willing sponge waiting to be squeezed yet again. In return for his financial help, Ruth agreed to keep in touch, periodically cook for him, and so she kept a spare set of keys to Goodwood Court.

On February 9th, Ruth leased a flat at 44 Egerton Gardens, a street of high, red brick buildings across from the Brompton Oratory in Kensington, and she and David moved in as Mr & Mrs Ellis. On February 22nd, David and Ruth were rowing again over his infatuation with the married woman at Penn, and yet again Ruth finished up with a black eye and severe bruising across her shoulders.

Early in March, Ruth, David and Desmond attended the British Racing Drivers Club dinner dance that was held in the Hyde Park Hotel. Ruth alternated the night, dancing with David and Desmond. In the early hours of the morning, Ruth retired to her flat in a drunken stupor and when she woke up, David was sleeping beside her. She kicked him out of the flat, and for the next week spent most of her free time with Desmond. She had started a modelling course, paid for by Desmond, who also financed a set of new clothes, and he drove her to the modelling school each morning and then picked her up, when her course was over.

Ruth had now discovered that she was pregnant. The identity of the father was hard to determine; it could easily been any of a number of men, but Blakely and Cussen must have been the prime contenders.

By the end of March, Ruth had miscarried and had an abortion. She later claims this was exacerbated by yet another fight she had with David. This time, he had smacked her in the face with a clenched fist and then struck her a severe blow in the stomach. The Findlaters, particularly Carole, did not believe that David was necessarily the father. Ruth had after all been living with Desmond Cussen as well as sleeping with David.

David had entered the Emperor in a race meeting on April 2nd at Oulton Park near Chester. On Thursday March 31st, David, Ant and Ruth drove north to Cheshire. Ruth and David booked into a hotel as Mr & Mrs Blakely. David never got to race his car, as it broke down during a practice lap, and was a write-off for the main meeting.

On the Saturday night, David and Ruth had a party at their hotel, along with Ant and his wife Carole, who had come up on the Friday evening to watch the racing. It was a pretty miserable night, and Carole Findlater later recalled that Ruth acted like the Snow Queen. David had bitched and moaned continually since his car had broken down, levering most of the blame on Ruth telling her, Its all your fault, you jinxed me. Ruth had responded by saying, Ill stand so much from you David, you cannot go on walking over me forever. He had replied, Youll stand it because you love me.

Ruth, dejected, and ill from a cold she had caught, returned with the party to London on the Sunday night. She was sick and tired, not just from the cold but also she was still suffering the effects of her abortion. On the Monday, Desmond came to see her at her flat in Egerton Gardens. She was feverish and had a temperature of 104 degrees; he insisted she stay in bed, while he went to pick up Andy from his school and bring him back to London for the Easter holidays.

Later Ruth recollected, I used to be good company and fun to be with. David had turned me into a surly, miserable woman. I was growing to loathe him, he was so conceited and said all women loved him. He was so much in love with himself.

And so began the decisive week that would bring all the loose ends together and finally resolve the end of the affair between Ruth Ellis and David Blakely.

But will my heart be broken

When the night meets the morning sun?

So tell me now, and I wont ask again

Will you still love me in the morning?

Gerry Coffin and Carole King.

For almost nineteen months Ruth and David had been feeding off each other. Like sharks, they had to keep moving all the time, trying to satisfy a hunger and quench the thirsts for their sexual and emotional appetites. They were very definitely creatures of chronic dependence. Addicted to alcohol, addicted to nicotine, they were also sexual predators, feeding of each others shortcomings and weaknesses.

Although Ruth was a woman of questionable moral standards, using both David and Desmond as it suited her moods, there seems little doubt that she craved and longed for a “proper” relationship with Blakely, but found it impossible to reconcile her deep desire for a monogamous relationship with his intransigent sexual marauding. And so they scratched and fought like alley cats, until she reached the end of her tether.

It came quickly in that second week of April 1955.

Andy was sleeping on a camp bed in the same bedroom as Ruth who, ill with the delayed effects of her operation and hung over with a heavy cold, could not have been good company when David came visiting. He was late home on the Monday and Tuesday evening, telling Ruth he had been seeing people about the Emperor. On the Wednesday, he came home early, bringing to Ruth a photograph he had just had taken. It was a promotional photo for the Bristol Motor Companys works team. David had been selected to race in the Le Mans event again, this time on June 9th. He had endorsed the photograph: “To Ruth with all my love, David.”

They had arranged to go to the theatre on Thursday night, but David was delayed and instead they visited a cinema. Ruth later claimed that all through the movie David was nuzzling her, telling her how much he loved her.

On Friday 8th April, the beginning of the Easter long weekend, David left early in the morning, about ten oclock, saying he had a meeting with Ant to discuss options that were open on the Emperor. He said he would be home early. He had promised Ruth that he would not visit Ant at his home, without telling her. Ruth distrusted both the Findlaters, but in particular Carole. David and Ruth had planned a day out on Saturday with Andy. Everything in the world seemed fine. Twelve hours later it had all turned to dust.

By 9.30 pm that night David had not returned to Egerton Gardens. Ruth rang the Findlaters. The first time she spoke to their 19-year-old nanny (Carole had given birth to a daughter, Francesca, in May 1954). She said there was no one at home. Later Ruth rang again and this time spoke to Ant. He said David was not there. Later in evidence, Ruth stated, “I knew at once that David was there, and they were laughing behind my back.”

Ruth had been riding a roller coaster for almost two years and now she knew it had stopped, perhaps forever. If only David had come to the telephone and spoken to her, it is likely she would have exhausted her pent up feelings, berated and abused him, and then gone back to loving him, as she had done so often in the past.

She wrote before her trial, “I just could not believe, after all I had been through, that David could be such an unmitigated cad as to treat me has he had. If only I had been able to speak to him and give vent to my feelings, I do not think any of this would have happened.”

Now it all changed. Psychologists know that there is a close homogeneity between love and hate. Ruth had loved David passionately and now she switched to hating him with the same emotional excess.

Throughout the rest of that evening, Ruth kept calling the Findlaters flat. Eventually, they removed the phone from its cradle. By midnight, Ruth was in a frantic and hysterical state. She called Desmond and he agreed to drive her to Tanza Road. When they arrived, she repeatedly rang the doorbell and hammered on the front door of number 29, but no one would answer. Ruth then set about smashing in the windows of Davids dark green Vanguard, a van that had been converted into a saloon. By now, it was about two in the morning of Saturday. Someone in the house called the police and an incident car from Hampstead Station arrived.

It is interesting to try to picture the scene in the street that chill, April morning. There was Ruth, screaming and yelling, abusing David and the Findlaters; there was Ant, in pyjamas and dressing gown, his hair mussed up from his disturbed sleep, hopping about trying to calm things down; there was the police, adopting their usual conciliatory approach to domestic incidents, and hoping like hell they wouldnt catch the back-end of some sudden, violent eruption. And there was Desmond, sitting in his big, black Ford Zodiac saloon, the very image of a benign benefactor.

The police eventually left after having calmed things down, but Ruth persisted in her demands to see David who, true to form, would be cowering somewhere, anywhere away from a potential source of violence. The Findlaters recalled the police, but by the time they had arrived, Desmond had coaxed Ruth into his car and driven off.

David was indeed staying at 29 Tanza Road. He had met up with Ant and Carole at the Magdala for drinks that Friday lunchtime. He told them, “Im supposed to be calling for Ruth at eight to-night. I cant stand it any longer, I want to get away from her.”

Carole had chided David, telling him, “that any man can leave any woman.”

In an amazingly well timed and prophetic statement, David had replied, “You dont know her, you dont know what she can do.” Within 60 hours, they would find out.

Ant and Carole persuaded David to stay with them over the Easter weekend. On Saturday morning, Ruth again telephoned the Findlaters address. The phone was lifted and then clicked down on her. Seething with anger and frustration, she went by taxi back into Hampstead and hid in the doorway of a house in Tanza Road, just down the street from number 29. She saw Ant and David come out of the house about ten oclock, inspect the damage she had done to the Vanguard and then drive off. She guessed, correctly, that they were heading into Mayfair to a garage owned by another of Davids motoring friends, Clive Gunnell. She waited a while and then, using a public telephone box, rang Findlaters’ number, only to have Ant hang up on her again.

Ruth returned to her flat in Egerton Gardens, made lunch for Andy and then packed him off to spend the day on his own at London Zoo in Regents Park. At about two oclock in the afternoon, Desmond drove her back yet again into Hampstead and dropped her off in Tanza Road. She had now convinced herself that David was having an affair with the nanny. A stout, buxom young woman of only nineteen, she was definitely not the prototype Blakely femme fatale. But by now, Ruth was losing control and was prepared to believe anything.

About four-thirty in the afternoon she saw the Findlaters, David and the nanny carrying the baby, leave the flat and drive away. Desmond picked her up and they drove back to her place. She fed Andy who had returned from his lonely expedition to the zoo, packed him off to bed, and then she had Desmond come around to pick her up. Their destination was yet again the northern suburb of Hampstead.

This was the fourth time in twenty-four hours she had made this pilgrimage to the house in Tanza Road. Although she had sighted David, she had not spoken to him since he had left her on Friday morning.

The Findlaters were hosting a party and the window of their second floor flat was open, voices drifting down into the dark, shadowy street. Consumed with jealousy and hate, she paced up and down the street, chain smoking, and no doubt ruminating on what had brought her to this junction in her sad and troubled life.

Because of David, she had lost her job. Because of David, she had lost the comfort and security of Desmond Cussens comfortable and expensive home at Goodwood Court. Because of David, she was broke. When she was arrested, she had six copper pennies in her handbag and her bank account was cleared out. She was sick and tired of waking up every morning feeling sick and tired; she had not slept for forty-eight hours. She was taking drugs — tranquillisers prescribed by Doctor Rees — and drinking heavily.

Eventually, Desmond persuaded her to go home and in the early hours of Sunday morning they returned to her flat. She would spend another restless and troubled night, fuelled by drugs and alcohol. By the breaking of the dawn, she would have made up her mind and committed herself to the only course of action she felt left open.

All of us are dwarfs mounted on the shoulders of giants, so that we can see further than they.

Bernard of Chartres 12th century theologian

On Easter Sunday, at about nine oclock, Ruth rang the Findlater flat for the final time. Eventually, Ant answered the telephone. Ruth said to him, “I hope you are having an enjoyable holiday, because you have ruined mine.” Ant hung up on her without replying.

In her trial evidence, Ruth stated that she could not recall how she spent her Sunday. She made Andy go to bed at about seven-thirty in the evening and at some stage during the day she took down all of Davids photographs, replacing them with ones of herself. She later said, “I was very upset and I had a peculiar idea I wanted to kill David.” She was no doubt drinking, more and more often; it was now Pernod, the deadly French apéritif.

At Tanza Road, the occupants were up and about making breakfast, dosing themselves with aspirin to ward off their hangovers, and bracing themselves for another day of attack and abuse from Ruth. At lunchtime, Carole, Ant and David met up with Clive Gunnell at the Magdala for drinks and it was agreed Clive would spend the evening with them at the flat. That afternoon, they all went up to Hampstead Heath and visited the Easter fairground which was in full swing there. David wandered around with his godchild, Francesca, perched on his shoulders. He was happy and relaxed and seemed to be enjoying his freedom from Ruth.

She was spending the afternoon and evening with Desmond, tanking up on Pernod. It was her third straight day with little or no sleep. Her frail, tiny body was fuelled on alcohol, nicotine, drugs and an aching desire for revenge on the man who had walked over her just once too often.

Later in the day, David and his friends returned to the Findlaters’ place and spent a quiet evening listening to gramophone records, drinking and smoking the hours away. They no doubt discussed many things. Ruth, and her frenzied activities throughout the last forty-eight hours would probably have featured prominently.

At about 8.45 pm, Carole ran out of cigarettes and David agreed to pop down to the Magdala and get her a fresh supply. Clive went along to help bring back some beer to top up their dwindling stock and they drove off in Davids car. The pub was less than a mile away, a good, brisk ten-minute walk for two fit young men, but they drove there nevertheless. Had they gone on foot, it is conceivable that the rest of the nights events would have unfolded differently. Had Ruth seen the car outside the house in Tanza Road, she may well not have confronted David, but driven off with Cussen and cooled down. Then again she might have shot not just David but anyone else who appeared on the scene, particularly Carole and Ant, who she had come to loathe.

Sir Isaac Newton once said, “I do not know what I appear to the world; but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy, playing on the sea-shore…whilst the great ocean of truth lay undiscovered before me.”

For Ruth, the time had come to cross that great ocean and finally come face to face with her own personal demons. Thirty minutes later, David Blakely was lying dead, his body torn and ravaged by gunshot wounds. Ruth herself had only thirteen weeks and two days before she herself would pay the ultimate price then required by the law to atone for her actions.

|