The Neptune Murders — Introduction — Crime Library

On Broadway, the play Godspell was going strong and Chorus Line was on its way to becoming a legend in American theater. The biggest movie that year was Network starring Peter Finch. The Oakland Raiders defeated the Minnesota Vikings 32-14 at the Super Bowl in January and the jobless rate in America was 8.4%. A controversy erupted when the film Death Wish appeared on TV for the first time. One of the biggest hits on television that year was Police Womanstarring the gorgeous Angie Dickinson. Kojak was in its heyday and President Carter was taking heat for his January pardon of Viet Nam era draft dodgers. At the Hollywood Sportatorium in Florida, 42-year-old Elvis Presley, appearing paunchy in a white sequined jumpsuit, sang his heart out before thousands of screaming fans. It was Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1977 and in New Rochelle, New York, a massacre was about to happen.

At about 7:00 AM in New Rochelle, a small city of 90,000 just outside the Bronx, Police Officer Chris Schraud, 29, sipped his coffee in a parking lot of the Thruway Diner, a well-known eating spot for interstate truckers who travel I-95. Schraud, a four-year veteran of the police department, worked the midnight to eight shift. It was his habit to enjoy a final cup of coffee before being relieved of duty by the day shift, due in at 7:45 AM. It was cold during the night, the temperature dropped a few degrees below freezing. As he looked out from his patrol car, he could see the first sunlight rising over the apartment buildings along Beechwood Avenue a few blocks away. A street sweeper truck, its steel brushes grinding into the pavement and kicking debris into the air, passed in front of the diner on its way up Boston Road. The driver absently waved to Schraud as the noisy machine lumbered past his patrol car. Across the street and behind him, the Neptune Worldwide Moving Company prepared for the hectic week ahead. Huge trailers were busy pulling in and out of loading docks, gearing up for their assignments for this busy Monday morning. The Neptune Company consisted of a large, two story office building facing the street and a huge warehouse and garage located in the rear section of the property. Over 300 people worked for the company in 1977. At this hour of the day, there was probably less than half that number actually on the job.

In the city streets, rush hour traffic continued to build as Officer Schraud placed the hot coffee cup on his dashboard and re-attached the lid. A smart cop never throws the coffee lid away because he realizes that in the next 30 seconds of his life, anything can happen. And somehow, cops believe that spilling coffee on their uniform is one of the worst things that can happen to them. They trivialize hand-to-hand combat which they see as a necessary part of their job, yet will bitch to high heaven if they are forced to change their uniform before the end of the tour. Officer Schraud took a few sips of coffee again and then eased the patrol unit out of the lot. As he made the right turn onto Main Street and began the five-minute trip to the police station to make his relief, Schraud thought about the warm bed waiting for him at home.

At the same time, a few blocks away from the young patrol officer, a brooding and angry man was driving his red 1971 G.T.O. down Weyman Avenue toward the Neptune Moving Company. Although he loved the feeling of power in a car like a G.T.O., he drove purposely slow. This was one morning he did not want to be stopped by some nosey cop. In the trunk was a fully loaded, expertly cleaned Saco .308 HK-41 semi-automatic assault rifle, the kind NATO troops carried. He was a large man, very large: 250 pounds, over 6 feet tall, 18-inch biceps and a massive chest. He had a skull and crossbones tattoo on his left arm and lots of other tattoos that depicted Nazi themes on different parts of his body. He was wearing khaki pants, a U.S. Army field jacket and a military style beret with the “death’s head” insignia embroidered on the front edge, the symbol of the dreaded Nazi SS. Underneath the jacket he wore a white “T” shirt bearing the emblem of the National States Rights Party, a thunderbolt, with the words “WHITE POWER” emblazoned on the chest. Tucked inside his belt was a 9-inch hunting knife, honed to a fine sharpness. He wore two .45 caliber automatic handguns and two other 9mm automatics, all fully loaded, in double shoulder holsters. On the front seat of the G.T.O. were also hundreds of rounds of various types of ammo, including .45 caliber, 9mm and 7.62 mm rifle cartridges in bandoliers. This rolling arsenal made its way up Weyman Avenue and turned slowly into the parking lot of Neptune where employees, scurrying around in their various jobs and responsibilities, barely took notice.

On the ground floor of the main building, employee Joseph Hicks, 60, an African-American, was walking through the hallway and saw his friend, Fred Holmes, 55, also black, approaching. “Hey Joe, morning to ya!” he called. Hicks had worked for Neptune for 25 years. The men stopped and exchanged greetings. Upstairs on the second floor, dispatcher Norman Bing, 31, sat in his office reading the daily runs. He usually arrived a little early on Mondays to plan for the week ahead. In the driver’s room, where most Neptune employees gathered before leaving for the day, employee James Green, 45, also an African-American and a company mover, picked up some papers and studied his route. He had caught a ride to work that morning with Joseph Hicks. Both men liked to be on the job early. On the first floor, sipping a cup of tea was electrician Pariyarathu Varghese, 32, who came to America from India the year before to get married. This was his second week at the job. His wife was employed as a nurse in the New Rochelle Hospital. Joe Russo, 24, a mover’s helper, was in the cafeteria, as were dozens of other workers shooting the breeze and doing what people do before they begin their workday.

The angry man parked his rumbling G.T.O. directly in front of two phone booths attached to the Neptune office building. Next to the phones, a double set of glass doors leading into a long hallway were slightly ajar. He opened his car door and stepped out into the parking lot, his military boots making a definite rapping sound on the cold pavement. His name was Fred Cowan.

At the Neptune parking lot, Cowan slammed down the trunk of his car while he held the assault rifle close to his side. He hugged it with two huge hands as he marched over to the entrance of the Neptune office building. Once inside the hallway, he immediately confronted Joseph Hicks who was still talking to Fred Holmes. Cowan quickly raised the assault rifle to his side and fired a lengthy burst at the men who were too shocked to react. Both fell to the floor dead. Other employees who were in the hallway fled in panic. Within seconds, the first of many phone calls was received by the New Rochelle Police Department from terrified Neptune employees who managed to get to the phones.

Cowan stormed down the hallway toward a large area off to the right, the driver’s room. He saw James Green inside and opened fire, hitting him in the back. He was instantly killed. The other drivers ran for their lives. Next, Cowan entered the dispatcher’s office, also on the first floor. He held the SACO rifle at the hip and sprayed the room with gunfire. Joseph Russo, 24, was hit in the stomach and chest. He fell mortally wounded. He would survive this day but would die six weeks later from his wounds.

Ronald Cowell, 39, was a Neptune employee who came face to face with the rampaging killer. But he was also a good friend to Cowan. As he tried to escape from the cafeteria, Cowan caught him by the exit door and placed the assault rifle inches from his head. “I had one foot out the door, and I was staring at the muzzle of the rifle he was carrying” he later told the reporters. “I started saying “Please!” and he (Cowan) said: ‘Go home and tell my mother not to come down to Neptune.’ I didn’t look back, I just kept on running!” (McFadden, p. 28 NY Times 2/16/77).

“Where is Norman Bing?” Cowan snarled. “I’m gonna fuckin’ blow him away!” he screamed. When Cowan reached the cafeteria where employees were having morning coffee, they were already in a panic. They saw the huge man, wrapped in bandoliers and handguns, bracing himself in a combat stance and firing at random. “It’s Cowan! He’s gone crazy!” some of them screamed. The cafeteria doors were quickly locked. One witness, Ed Miller, crouching in terror, saw Cowan fire a burst through the front door. Cowan then reached inside to unlock the door and cut his left hand on the shattered glass. The employees locked themselves in various offices and closets to escape from the madman. Cowan fired several bursts into the cafeteria striking the walls and furniture.

Neptune employee Howard Schofiled later told The Standard Star: “People were screaming and everyone was either seeking shelter or bolting out the doors. When I saw bodies on the floor in the office, I ducked under a desk with another worker. We cowered there expecting the worst” (O’Toole, p. A2).

Cursing loudly and screaming for Norman Bing, Cowan continued down the hallway. Near the stairwell, he saw Pariyarathu Varghese running from the area and immediately shot him. Varghese died on the spot. Meanwhile, Norman Bing had already jumped behind a desk and was down on his hands and knees. Lucky for him, Cowan didn’t notice. He was busy wrapping his bleeding hand with a rag. Bing, who was Cowan’s supervisor, suspended him from his job two weeks before. He had refused an order to move a refrigerator and Bing decided he could not ignore the situation. Cowan was supposed to return on February 11 but didn’t show up. As he lay hidden beneath an office desk, Bing could hear Cowan stalking through the hallways, indiscriminately firing the rifle into the walls and offices. “If I hadn’t walked out of my office, he would have gotten me. I heard the shots and I knew he was after me, he made that clear” he later said to reporters from the Times (Thomas, p. 28 2/16). But Bing had another reason to worry: he was Jewish. To Cowan, that was enough.

Cowan marched off into the rear portion of the Neptune office building and climbed the empty stairs to the second floor. He proceeded to the north end office of Vice President Richard Kirschenbaum, which was abandoned. He removed two handguns from his holsters and laid them on the VP’s desk. The windows of this office, as was the entire Neptune building, were coated with a tinted Mylar composite, which filtered out the sunlight. It worked very well. Although people inside the office could see out, people outside could not see in. Cowan felt safe behind the tinted glass. Although in pain, he straightened his back, mindful of the correct posture of a good Nazi soldier. He tended to his wounds, seething, brooding, scowling at the world with an anger that never left him. A world that never behaved in the way he wanted it to. And for that reason, he blamed the police, the Jews and the blacks.

At 7:45 A.M outside the New Rochelle Police station, Officer Schraud waited by his patrol car as his day relief, P.O. Allen Mcleod, 29, approached on foot. Mcleod, a six and a half year veteran of the department, had received a medal the year before when he managed to take a gun away from a bank robber. “He was a man of few words” said Chris Schraud recently, now retired. “He was a good cop, did his job, we called him “Deputy Dog,” but it was meant in a good way, it was a compliment,” Schraud went on to say. Mcleod was a former correction officer in Westchester County. He became a cop in 1970 and lived in Mamaroneck, a small town located near New Rochelle with his wife and two kids.

“Hey Chris, what’s happening?” he said that morning.

“Nothing much, a ten-eight (family dispute) earlier, otherwise a quiet night. I topped it off for you, you’re good to go.”

“Thanks buddy!” Mcleod said as he walked around the patrol car, a cigarette dangling from his lips, checking for any damage for which he may later be held responsible. The door of the patrol unit was open and the radio could be heard clearly in the cold morning air.

“Central to Car 2”

Mcleod grabbed the dashboard mike and answered.

“Two”

A female dispatcher’s voice, betraying a slight sense of boredom in its tone and demeanor, gave a reply.

“Two, respond to Neptune Movers on Weyman Avenue. Report of man with a gun. Your time is zero seven fifty.”

Schraud, relieved that he missed the detail, joked with Mcleod.

“Better you than me, pal” he said as he picked up his briefcase and walked toward the rear door of the station house. Police Officer Vinnie Juliano, 29, also being relieved from the midnight tour, held the door.

“Hey, Chris!” he said.

“Thanks, Vinnie, quiet night right?”

“Yup, homeward bound” Juliano replied as he walked to the front desk. Schraud signed off his memo book, dropped it on the sergeant’s desk and headed for the locker room. Juliano signed off his own book and shoved it across the countertop to the sergeant. Just then, he noticed something unusual. “I saw the phone switchboard light up like a Christmas tree. It was if everyone in the city called the police at the same time. I didn’t know what it was, but something was up” he said.

In what would turn out to be the last job for Patrolman Allen Mcleod, he pulled the 1975 Dodge out of the police yard, switched on his roof lights and headed into a firestorm.

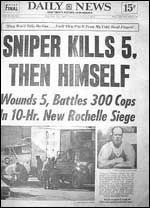

(New York Daily News)

Frederick William Cowan was born June 1, 1943 in New Rochelle. He attended Blessed Sacrament Elementary School and graduated in 1957. He was an exemplary student throughout his entire 8 years at the school. One teacher said of Cowan: “You were glad to have him in your room. He had neat handwriting and always had his work done on time” (Roddy, Keefe and Kavanaugh, p. A3). Cowan went to Stepinac High School in nearby White Plains, a fine Catholic institution where he again excelled and played on the football team. Upon graduation in 1961, he enrolled in Villanova College for Engineering and remained there until he suddenly dropped out in 1962 and later joined the Army. In 1964 he got into trouble while stationed in Germany. By himself, Cowan lifted up a Volkswagen car and turned it over. He smashed up the car with his bare hands and was sent to the stockade after a court martial. The following year in 1965, Cowan left the scene of a car accident in Germany and was again threatened with jail time. He was given a general discharge and sent back to the States in March of 1965. However, when he returned to New Rochelle, he had changed.

Although Cowan was interested in guns even as a boy, as an adult he also developed an obsessive interest in Adolph Hitler and the Nazi Party. He collected all sorts of Nazi memorabilia: WWII helmets, swords, guns, swastika flags,

Gestapo posters, berets and more. He read a great deal of Nazi propaganda literature and talked often of his hatred of blacks and Jews. But there was more. Inside a book, later found in his room on Woodbury Street in New Rochelle, Cowan had scribbled these prophetic words: “Nothing is lower than black and Jewish people except the police who protect them” (McLaughlin, Peter, p.3). Some other Neptune employees knew of his fondness for Nazism while others did not. At the local bars in New Rochelle, where Cowan would stop in for some beers or to cash his paycheck, it was a different story. Some people said Cowan’s hero was Nazi SS General Reinhard Heydrich, a commanding officer of German concentration camps during World War II. After a couple of beers, Cowan preferred to be called “Reinhard” (Roddy, Keefe and Kavanaugh, p. A3), an indication of where his mind was focused. And so, over the years, perhaps fueled by his repeated failures and a consistent resentment toward society in general, the Nazi poison ate away at his heart and mind until all he could understand or feel comfort in, was hate.

Inside the deserted office on the second floor of Neptune, Cowan picked up the phone and listened for the dial tone. Later, he would use that same phone to demand food from the police. He slammed the receiver back down on the cradle and began to wrap his bleeding hand. The cut appeared to need stitches but it would have to wait. He reloaded the SACO rifle with a fresh magazine and cocked the sliding bolt. He checked his handguns and adjusted the two bandoliers he had draped across his barrel chest. Perhaps at that moment, on the wall, he saw reflections of flashing red lights and cautiously peered out the front window.

Police Officer Mcleod drove radio car 2 (RC2) into the front parking lot of Neptune with roof lights fully activated. He guided the patrol car to a stop about 15 feet from the door where Cowan had entered just minutes before. Mcleod had no idea that already several people lay dead inside. He saw several employees running through the side parking lot. For the first time, he may have realized the seriousness of the situation. His hand moved instinctively toward his .357 magnum, resting in its holster. Cowan, still up on the second floor and hidden behind heavily tinted glass, watched the defenseless cop exit his patrol car. He put the rifle to his shoulder, took careful aim and fired a burst through the office window. The rounds hit Mcleod in the head, chest and heart. He was killed instantly, leaving his young wife without a husband, his little kids without a father. As he lay on the ground, Cowan fired several more rounds at Mcleod’s body. Such was the man’s hatred.

Simultaneously, other police cars roared onto the scene. Police Officer Ray Satiro, 28, jumped from his car and attempted to assist Mcleod. Cowan opened up with full force, firing dozens of rounds from his semi-automatic weapon. The cops bolted for safety. Officer John Fitzgibbons ran from his unit and sought cover behind an open door. A bullet went through his right hand. Seconds later, Lt. Vincent Fontanarosa, the road supervisor, arrived at the scene and immediately crashed into a parked car as the bullets rained down upon his police cruiser. Later, eleven bullet holes were counted in his radio car including five directly through the front windshield. Fontanarosa was hit in his upper arm but returned fire at the second floor window, emptying his revolver in the process. He screamed over his radio for help. Meanwhile, Satiro, seeing Mcleod motionless on the ground, briefly took cover behind a telephone pole. In an act of true courage, while bullets ricocheted off the pavement around him, Satiro, a 1966 Viet Nam veteran, decided to act. He made a frantic dash to pull Mcleod’s body to safety. He could not have known that Mcleod was already dead. As he ran to assist the fallen officer, Satiro took a bullet in his right leg and crawled back to cover. He would survive but the wound would plague him for the rest of his life.

through the windshield

As desperate cries for assistance from the trapped officers went over the police radio, an army of cops descended upon the scene. Shots repeatedly rang out from the second floor office at Neptune. The siren on RC 11 had been left on, emitting an ear-piercing, steady wail. Within minutes, the siren roof unit was shot out by Cowan. Over 100 rounds were fired in the first few minutes of the battle. Police snipers arrived, including Officer Schraud who was pulled out of the police locker room as he was changing from his uniform to go home. “When I got there, it looked like World War III. Me and another detective found an abandoned office in a building across the street. We had a good line of fire on Cowan but we couldn’t see him behind the tinted glass. It was very frustrating!” he said. Soon, New Rochelle Police Commissioner William Hegarty arrived and a command post was set up next door at the Schaefer grocery building. Panic-stricken employees fled the besieged office building sometimes bumping into cops who were scurrying around to locate good firing positions. More than one employee was put down on the ground under gunpoint by cops, fearful it may be the shooter who was attempting to escape. It was pandemonium. And all during this time, Mcleod lay on the cold, barren pavement, unable to be rescued, a cruel reminder of any police officer’s uncertain destiny and the finality of death. Schraud recalled the awful scene: “I saw him laying there. The gunfire, it was so intense, we couldn’t help him. It brought tears to my eyes.”

The police brass at the command center struggled to gain control of the scene. The first goal was to understand exactly what happened. It is not easy to determine the true nature of such a situation until enough facts can be gathered and witnesses can be interviewed. Police at the early stages of this incident did not know how many suspects there were inside Neptune or if they had hostages. They were not even sure if Cowan was acting alone.

Ambulances from all over Westchester County rushed to the scene. One ambulance got too close to the Neptune building and Cowan fired a burst from the upstairs office. A bullet went through the windshield of the ambulance between the two EMTs. Police snipers, positioned on two separate rooftops, one across the street and another atop the Schaefer grocery building, tried in vain to get a clear shot at Cowan still hidden behind the cursed tinted glass.

Detective Robert Harris, 41, Viet Nam veteran, responded to the scene a little after 8:00 AM. Racing to Neptune with lights and siren blasting, he turned onto Weyman Avenue. At that moment, bullets came crashing through the windshield, shattering the glass into his face. Harris immediately slammed on the brakes and punched the car into high speed reverse. “I had visions of Viet Nam. The windshield was blown out. I thought I burned out the tranny ’cause I shifted so hard. I backed that car up right through a plate glass window of an electronics store,” he said recently. Harris jumped from the car and took cover. Down the street, he was amazed to see crowds already assembled even though bullets were bouncing off the pavement. “I couldn’t believe people were there!” he said, “I got down on my hands and knees right away.”

For the next hour, police and company supervisors tried to account for all Neptune employees. There were unconfirmed reports that up to 30 men and women were hiding in locked bathrooms and closets too terrified to come out. During that first terrible hour, periodic bursts were fired from Cowan’s position at the police snipers across the street. The police returned fire but were unable to get a direct line on the crazed gunman, safely obscured by the heavy window tint.

Police borrowed two delivery trucks from the Schaffer grocery company. P.O. Juliano, who like Schraud was held over from the midnight tour, took cover behind one of the trucks. They carefully backed up the vehicles toward Neptune where the wounded officers waited for rescue. “We stayed close to those trucks, believe me. They blocked Cowan’s view as we got closer to where Satiro and Fitzgibbons were” said Juliano. “We couldn’t get to Mcleod though, the fire was too heavy” he added. Lt. Fontanarosa, Officers Satiro and Fitzgibbons, all wounded, were safely evacuated and conveyed to the hospital. Mcleod, however, lay exactly where he fell. At about 9:15 AM, a call was made to the New York City Police Department. A tank was needed in New Rochelle, was there one available?

On Weyman Avenue and in the surrounding area, massive crowds began to gather and were quickly pushed back by police. Bullets from Cowan’s high-powered assault rifle had struck buildings, shattered windows and hit parked cars several blocks away. The media arrived and set up wherever they could. Live feeds were established to television and bulletins went out over T.V. and radio urging citizens to stay away from the south side of New Rochelle until the incident was resolved. Many police departments in the area, such as Pelham P.D., White Plains P.D. and Westchester County sent help to the scene. Soon, there were hundreds of police officers, dozens of police vehicles from various commands and high ranking police brass from different cities and towns, all on separate radio frequencies eager to help. Estimates later indicated that over 400 cops were at Neptune at one time or another during the day.

At about 10:30 AM, a tank rolled down the city streets. A twenty-ton armored personnel carrier was quickly transported to the scene by the New York City Police, striking cars and causing several accidents along the way. The police weren’t wasting any time. The APC could be used as an offensive weapon if need be. But for now, it had a sacred mission. With several police officers crouched behind the massive vehicle, the APC approached the parking lot where RC2 was still parked and next to it, Officer Mcleod’s body. Hundreds of officers watched and prayed as the vehicle inched closer and closer to the fallen hero. Every cop at the scene realized the awful truth: that it could have easily been any one of them laying dead on the ground. Such is the nature of the job. Death or life is decided in a chaotic process that is mostly unpredictable. That is why cops often find religion during their careers. They may not attend church or practice it in a formal way but they develop a strong faith in God and in some sort of ultimate justice that they believe must prevail.

The massive APC pulled directly in front of Mcleod’s body. Two New Rochelle officers carefully picked him up off the ground and pulled the body inside the vehicle. He was removed from the scene and all cops breathed a little easier.

“Mcleod is no longer with us!” someone announced over the police radio.

A search and rescue team of F.B.I. agents and New Rochelle police was hastily put together. Armed with automatic weapons and shotguns, they entered the Neptune building to clear the first floor of any trapped or hiding employees. Entering through a rear door that was out of the line of fire from Cowan’s position, the cops went on a nerve-wracking search through a myriad of offices and closets on the first floor. Into each nook and cranny they searched, behind every door and desk they crawled, never knowing in the next moment if sudden death would appear from the muzzle of a high-powered assault rifle. For what seemed like an eternity, the officers continued on their mission. P.O. Juliano was one of the eight officers on the team. “We knew there were people still inside, we just didn’t know how many” he said. “When I got inside the cafeteria, I saw a guy crouched under a desk, too terrified to move.” When Juliano coaxed the man out, he began to back him out of the building. “As I moved with him down the hallway, I shouted ‘Civilian! Civilian coming out!’ so the other cops would know who he was. Tensions were very, very high,” he remembered. The search party also found the bodies of Hicks and Holmes together in the first floor hallway, Cowan’s first victims. James Green was found next. He suffered fatal wounds to the back and chest. Pariyarathu Varghese’s body was found minutes later near the back stairwell. Joe Russo, badly wounded in the abdomen was in the cafeteria along with several others who had been shot and wounded. It was like a small war scene. And hidden under a desk in a first floor office was Norman Bing, terrified, trembling and glad to be alive. “If I hadn’t walked out of my office, he would have gotten me. He kept asking people if they knew where I was-thank God nobody did!” he later told reporters from the N.Y. Times (Thomas, p. 28 2/25). In this first search mission, cops located 14 employees who were either hiding or wounded and brought them to safety outside the building.

The scene inside the radio room at the New Rochelle Police headquarters was turbulent. All off duty officers who could be contacted were ordered to active duty. The entire department was on full alert and every police officer was needed immediately. Every weapon, automatic rifle, handgun and shotgun was removed from the armory and brought to the Weyman Avenue battleground. The department was engulfed by hundreds of phone calls from reporters, citizens, relatives of Neptune employees, the families of the wounded and dead, other cops, anyone who had anything to do with Neptune or the police department called the switchboard that day. Volunteers, including some City Council members and local politicians, responded to the police station to offer their help.

At 12:13 P.M., the phone rang on an open line on the switchboard. The call was taken by Police Lieutenant Tom Perotti who was surprised to hear Fred Cowan’s voice on the phone. He was calling from inside Neptune and wanted food.

“Hello?” said Perotti.

“Who the hell is this?” the voice demanded.

“Lt. Perotti.” The caller identified himself as Fred Cowan, the shooter at Neptune.

Cowan said that he wanted some potato salad and hot chocolate.

“I get mean when I’m hungry!” he said which struck Perotti as a serious understatement. Perotti asked how he wanted the food delivered.

“Just drop it off at the door!” Cowan shouted into the phone. When Perotti expressed concern about the safety of his men and women, Cowan reassured him.

“All I want is the food and I’m not going to hurt anybody at this point.” He went on to apologize for causing such an inconvenience. “Tell the mayor I’m sorry for causing all this trouble”, he continued. But when Perotti tried to keep him on the phone, Cowan became abrupt.

“Just get the goddamn food!” he shouted and hung up.

In the command center next door to Neptune, officers worked relentlessly to establish communication with Cowan who was showing no signs of responding. A loudspeaker was mounted on the APC and continuously urged Cowan to call the command center. His parents were brought to the scene and also made several pleas for Cowan to surrender. He still would not reply. “Pray for Freddie, he’s gone crazy!” his mother said (McFadden, p. 28). Det. Harris, who talked to Mrs. Cowan at the scene, said the mother was in fear of her son. “She told me that she was afraid of Freddie ever since he came back from the service,” he said. The situation evolved into a sort of stalemate. At about 2:15 PM, a Neptune employee, Sal DeBello, who was trapped in a bathroom on the second floor, emerged from the building unharmed. He told police that he did not know exactly where the gunman was but knew that another employee, William Hill, was in another second floor bathroom too afraid to come out. While cops debriefed DeBello, another employee, Nicholas Siciliano, wandered into the rear parking lot. He said that he was hiding in the ladies’ room on the second floor. Cops now had no doubts that there were other employees still unaccounted for and probably either hiding or taken hostage by Cowan.

At about 2:45 PM, a decision was made to enter and search the 2nd floor of Neptune. No shots had been fired for several hours and although Cowan had spoken on the phone with Lt. Perotti at 12:30 PM, no one could state that the suspect had been seen or heard from since then. Sgt. Bill Augustoni, 43, a 15-year veteran police officer was picked to command a small assault team to enter the 2nd floor area of Neptune. Moments before they began the search, a single shot rang out from inside the building. But no one could say exactly where it came from.

The assault team consisted of four officers and Sgt. Augustoni. They entered into the maze of hallways and offices on the second floor where none of them had ever been before. Blood flowed down the steps and bullet holes were clearly visible on the walls and through doors where Cowan had fired indiscriminately just hours before. Carefully, ever mindful of what could lay behind the next corner, the team made their way up to the second floor. Outfitted in thick flak jackets and steel helmets, armed with heavy weapons, the men quickly became drenched in their own sweat. Sure that Cowan could hear their pounding hearts, Augustoni guided the team to Vice President Kirschenbaum’s office, the last known location of the suspect. As he approached the target room, Augustoni hugged the wall, wishing there were more places to hide, more closets to jump into, more recesses where he could disappear from view, away from the deadly sights of a berserk killer who had nothing to lose by killing another cop. The door to the office was ajar and the team was able to look inside. They got their first glimpse of what they believed was Cowan laying on the floor near a desk. With weapons at full ready and every man’s finger on every trigger, they entered the room. If a floorboard had creaked, if a paper had fallen off the desk or a fly had landed inside that room, all guns would have been blazing. But it was quiet. In the north corner of the room, Augustoni and his men saw a body, laying face down. As they got closer, they could see a large pool of fresh blood under and near the head. It was a large man, wearing an Army field jacket, combat boots and two shoulder holsters. A bloody beret lay near the desk. A gaping bullet wound to the side of the head was plainly visible. Clutched tightly in his right hand was a .45 caliber automatic. Another handgun lay on the floor next to Cowan’s left side. A 9mm automatic was situated on the desk along with several ammo clips for the SACO rifle and military style ammo pouches. The other 9mm was still in its holster, blood dripping from its handle. Next to the corpse, leaning against an office chair was a SACO semi-automatic assault rifle. Various ammo clips were strewn about the office floor mixed in with dozens of expended rifle shells. There were bullet holes in the desk and in the walls, through the windows and the doors, a testament to the accuracy of police snipers and Lt. Fontanarosa’s response to Cowan’s first barrage. It was over. Cowan was dead, apparently by his own hand. It was 5:40 PM, almost 10 hours since the massacre began.

“The perpetrator is dead” Sgt. Augustoni reported over the radio to the relief of everyone. To ensure there were no bobby traps or other surprises, a special bomb squad was called in to effect a systematic search of the body and the immediate scene. Cowan was officially pronounced dead at 6:00 PM by the City Physician. “I wanted him alive” Harris recalled, “We wanted some answers, some meaning to what he did and why he became that way.” Inside the killer’s pocket, police found a membership card for the National State’s Rights Party in the name of Mr. Frederick W. Cowan. On the reverse side of the card, it listed several membership principles. They included “A free white America, Racial Separation, Expulsion of All Jews and Confiscation of ill-gotten Jewish Wealth.” And on the bottom of this same card, the party’s slogan read “Honor, Pride, Fight-Save the White.”

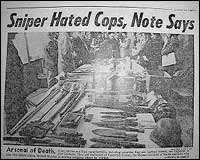

siege

New Rochelle Police eventually executed a search warrant at Cowan’s home on Woodbury Street. Found during that search was a terrifying array of Nazi mementos that astonished the police and gave an indication of just how disturbed Cowan had become. When Det. Harris first entered the room, he was shocked. “I didn’t know Fred, but his family were very nice people. I didn’t know how a person could go that way, have such negative feelings about Jewish people and blacks,” he said during an interview. Inside the attic apartment police found eleven cans of gunpowder, shotgun shells, primers, three antique muskets, one rifle, shell casings and equipment to make bullets, thousands of rounds of ammunition, one machete, at least 20 knives, eight Nazi bayonets, military helmets from World War II, five posters of Adolf Hitler, dozens of Nazi books, literature and many SS items, flags and belt buckles.

1977

Over the next few days, newspapers published a wide assortment of stories about the incident at Neptune. “Sniper Hated Cops, Note Says” wrote the New York Daily News. The New Rochelle Standard Star was more direct: “Gunman Idolizes Hitler and the Nazis.” The New York Times focused in on the racial aspects of the incident “Police Link Slayer of Five To a Militant Racist Party.” Follow-up police investigation suggested that Cowan was a member of the National Sates Rights Party, a militant racist organization that encouraged the use of uniforms among its members. The group was founded in Knoxville, Tennessee in 1958 and was based on Marietta, Georgia in 1977. The organization took on a lightning bolt image as its logo and also published a newsletter called “The Thunderbolt.” Copies of the newsletter were found in Cowan’s apartment during the police search. The thunderbolt was also the emblem of Hitler’s youth organizations in Germany during the 1930s. But in America it’s not a crime to join such radical, unorthodox groups. Police Commissioner Hegarty emphasized that point when he told reporters: “This kind of act can never be prevented in this kind of society, where people are protected by the Constitution and a variety of laws” (Feron, p. B6).

On Thursday, February 17, a funeral was held for slain Police Officer Allen Mcleod. Over 4,000 police attended, some from as far away as Georgia.

officer Allen McLeod

(AP)

A wave of blue paraded down city streets as the tears flowed for the cop’s young wife, Donna, and her two fatherless children. Few events are as heart wrenching as a murdered cop’s funeral. Maybe it’s the tragedy of a life taken so young and for reasons that never seem good enough. Maybe it’s the concept of death in the service of honor, the sacrifice of oneself for the common good. Or maybe it’s just the utter senselessness of it all. Bagpipes played their mournful sound, the stirring verses of “Amazing Grace” sweeping over the multitude between the tears and the grief, its haunting melody lingering in the air until each person felt the bitter lump in their throat, the cold chill down their spine. The long, solemn procession led up Mamaroneck Avenue, past Stepinac High School where Cowan once attended classes and into the City of White Plains. He was laid to rest, Police Officer Allen Mcleod, 32 years old, whose only fault was being a good cop. He paid for the privilege with his life.

Six weeks after Cowan shot himself on the second floor of Neptune, he claimed his last victim. Joseph Russo, 24, who was shot in the cafeteria on the morning of February 14, died at New Rochelle hospital of his wounds.

Today, nearly 24 years later, a great deal has changed in the City of New Rochelle. The Neptune complex has long since been torn down. A massive Home Depot store has been built in its place and many who are not familiar with New Rochelle are not aware it even existed. Most people today never heard of the Neptune shootings, although in New Rochelle, it is well remembered. Seven plaques hang on the wall of the police station memorializing officers who died in the line of duty over the years. A plaque is dedicated to P.O. Allen Mcleod, one of the 93 police officers who were murdered in America during 1977.

A wave of lawsuits and litigation arose from the Neptune incident and continued for many years. P.O. Fitzgibbons retired as a result of his wounds at the warehouse. P.O. Satiro, who tried in vain to save Mcleod’s life, was later promoted to Sergeant but suffered continually from leg pain. He died in 1997 while jogging. P.O. Schraud was severely injured when he fell down a flight of steps while chasing a burglary suspect in 1986. He was forced to retire. Cancer claimed the life of Sgt. Bill Augustoni in the mid-eighties. Detective Robert Harris retired safely in 1989. Officer Juliano is in his 28th year as a police officer in the City of New Rochelle. Neptune Worldwide Moving Company shut its doors during the early 80s and Commissioner William Hegarty later became the police commissioner of Flint, Michigan.

According to all the available information, some people in the neighborhood knew about Cowan’s hatred and his adoration of Nazism. But no one thought that he would ever act on those beliefs. Not many people even believed that Cowan was a violent man. A neighbor once told reporters: “I’ve known him over 30 years. I saw him grow up. He was always very quiet and you couldn’t find better people than his parents” (Cavanaugh, p. 1).

By the year 2001, in a nation still numb from the shock of incidents like Columbine, Oklahoma City and other mass killings, the Neptune incident seems remote by comparison. But it was rare in 1977 for America to witness such violence committed in the name of Nazism, a horror for which the world spilled an ocean of blood only a generation before. Cowan became a symbol of a frightening trend in society that was just beginning during that era. The white supremist groups like Ayran Nation, National States Rights Party and the Neo-Nazi movement were not widely publicized in 1977, though such organizations were already known to the police. After Neptune, law enforcement began to pay special attention to these militant groups and their frightening potential for violence. In the police search of Cowan’s attic apartment on February 14, a thick metal belt buckle was found among his belongings. Inscribed boldly on the front of that buckle were these prophetic words: “I will give up my gun when they pry my cold dead fingers from around it!”

This article was prepared using newspaper articles, official records and personal interviews with Det. Christopher Schraud (ret.), Police Officer Vincent Juliano and Det. Robert Harris (ret.)

Cavanaugh, James, Gorlach, Robert and Graham, Victoria. “Man With a Gun: Nazi Enthusiast, “Sensitive” Pupil,” The Standard Star. February 15, 1977, p. 1.

Feron, James. “Police Link Slayer of Five To a Militant Racist Party,” New York Times, February 16, 1977 p. B6

McFadden, Robert D. “New Rochelle Gunman Kills 5 and Then Himself,” New York Times, February 15, 1977, p. 1

McLaughlin, Peter The New York Daily News February 16, 1977, p. 3.

O’Toole, Jim. “Let’s Get Out; He’s Gone Crazy” The Standard Star. February 14, 1977, p. A2

Roddy, Michale, Keefe, Nancy Q. and Kavanaugh, Jim. “Fred Cowan and Joe Hicks in Life and Death,” The Standard Star. February 20, 1977, p. A3.

Thomas Jr., Robert McG. “Supervisor Sought by Cowan Hid Under a Desk as Killer Searched,” New York Times February 15, 1977 p. 28