William Randolph’s Hearse — “Rosebud” — Crime Library

“Rosebud… ” the dying man gasps with his last breath, slumping backward in his chair. The glass ball clutched in his hand falls from his grasp onto the floor and rolls down the marble staircase. As it shatters, water and fake snowflakes spill out. A nurse enters the room and folds his hands across his chest, pulling a sheet over his head. So ends the life of Charles Foster Kane in the opening scene of Orson Welles’ classic film, Citizen Kane.

As the tributes to the late Mr. Kane pour in from around the world, an enterprising newspaper reporter named Jerry Thompson is assigned by his editor to decipher the significance of the dying man’s final word. The quest to solve this mystery takes Thompson on a serpentine journey into the life of a newspaper publishing tycoon considered one of the giants of the 20th century.

The story is, of course, fictitious. Or is it? Just who was Charles Foster Kane and who or what was “Rosebud?” Welles knew those answers when he started shooting the picture. By the time it was completed, everyone else knew, too. Including the man on whose real-life persona the fictitious Mr. Kane was based.

His name was William Randolph Hearst.

Until Citizen Kane was released in 1941 few people with any stature ever dared to say anything publicly unfavorable about the then-76-year-old media mogul. Commanding a coast-to-coast empire of 28 newspapers and 18 magazines with combined circulation well into the tens of millions, along with radio stations and film production companies, “Willie” Hearst was the Rupert Murdoch of his time. He could destroy nearly anyone’s life and career with a single headline, and he often did. He could incite wars and, in one notable instance, he actually did. He clashed with powerful presidents, including Theodore and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Clearly, Citizen Hearst was not a man to be trifled with.

Welles, at that time, was a novice, 24-year-old prodigy. He had never made a motion picture before, but his convincing narration on the 1938 radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds set off a nationwide panic and made him a celebrity. Despite his lack of hands-on filmmaking experience, he knew going into his bold venture that “You don’t pick a quarrel with a man who buys his ink by the barrel.” But he made the picture anyway.

To his dying day in 1985, Welles continued to insist that Citizen Kane was not just about Hearst. He claimed that the Kane character was a “composite” of several powerful individuals at that time. However, Hearst remained unconvinced and he and his cohorts made every effort imaginable to stop the picture from being released. From threats to blackmail to boycotts.

All-powerful MGM Studio Chief, Louis B. Mayer, offered RKO Pictures, with whom Welles was contracted, $800,000; a healthy sum that was far more than the picture was expected to gross at the box office. Mayer’s sole purpose, at his friend Hearst’s urging, was to acquire the negatives and destroy them.

When that effort flopped, Hearst tried to destroy Welles himself. Hearst newspaper headlines and gossip columns trumpeted the scandal of Welles’ affair with actress Delores Del Rio while she was still married. And when the film finally was released, none of the Hearst newspapers carried any mention of it. Nor would they accept advertising from any of the theaters showing the picture.

What was Hearst afraid of? What was he trying to hide? Or… more to the point… who was he trying to protect? Himself… or someone else? Most of Hollywood at the time knew the answer to that question. Especially the critics.

As the two-hour film winds down, reporter Thompson is no closer to discovering the identity or significance of “Rosebud” than he was at the beginning of his investigation. Some of those he interviewed who were closest to Kane during his life and career are no help. Most of them have provided no clues, while some others can only venture wild guesses. Thompson himself finally concludes that it will just have to remain a mystery. A missing piece in an unfinished jigsaw puzzle symbolic of Kane himself, and his life.

However, after Thompson and his fellow reporters exit the scene, a workman handling the contents of Xanadu, the late Kane’s palatial estate, picks up a child’s sled and throws it into an incinerator. As he does, film viewers see the name “Rosebud” on the front of the sled, along with a picture of one. As the sled burns and the name melts away in the intense heat, thick black smoke billows out of the chimney and the credits roll. The movie is over.

Could the “Rosebud” sled have been symbolic of Charles Foster Kane’s lost childhood? A childhood that was stolen from him in the middle of the winter when his mother, heir to a Colorado mining fortune, signed papers allowing young Charlie to be raised by a prominent financier in Chicago and New York. Is that what the dying Mr. Kane was thinking about in his final moments on earth? Was that why the snow globe was clutched in his hand when his life’s clock finally stopped?

That may have been the symbolism Welles was trying to convey to his audience. However, there is a more plausible explanation in the real world of William Randolph Hearst. “Rosebud” was the nickname Hearst reportedly gave to the clitoris of his long-time mistress. A loyal companion who gave him great pleasure for 35 years. That’s who and what Kane’s character was likely thinking about when his time on earth expired. That’s who the real-life Hearst was trying to protect in his attempts to suppress the movie’s release… or so it was widely believed. But perhaps it was even more than that.

Maybe he had something else to hide. A deep, dark secret he didn’t wish to be reminded of. Perhaps Welles’ movie rekindled memories of a grisly, tragic incident that took place on his yacht 17 years earlier. A mysterious death that could tarnish the name and reputation of his beloved mistress.

Her name was Marion Davies.

It was 1924, the height of the “Roaring ’20s.” An era of flapper girls, speakeasys, hot jazz, carefree spending, and wild living. Calvin Coolidge was elected president for a full term. Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators knocked off the powerful New York Giants in the World Series. Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Red Grange and Bobby Jones ruled over their respective sports. An unknown Oklahoma thoroughbred, Black Gold, won the Golden Anniversary running of the Kentucky Derby, while gangsters and gamblers were running Chicago and New York. Prohibition was in full swing and hard liquor never enjoyed greater popularity. Rudolph Valentino, Charlie Chaplin, Pola Negri, Clara Bow, and Theda Bara were the hottest items on (and off!) the silent screen. The Charleston was all the rage. Life was good in 1924, especially for those who could afford the best of what this prosperous, blissfully isolationist, self-indulgent era had to offer.

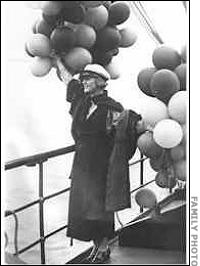

As the dapper, handsome man in his early 40s ascended the gangplank to the 280-foot yacht moored in San Diego Harbor on November 15, 1924, his eyes opened wide. A broad, closed-mouth smile crossed his face. Awaiting him on deck was a large cluster of red and white balloons blowing in the light sea breeze. A stunningly beautiful woman in a long, dark coat and sailor’s cap, with short blonde hair stylishly cut halfway down her neck, was waving to him. As he stepped onto the deck she came forward with a broad, cheery smile to greet him.

“Happy birthday, Mr. Ince,” the slightly stuttering voice chirped. She threw her arms around his neck and kissed him on the cheek. He lightly grasped her by the shoulders, kissed her on the cheek, and stepped back.

“Thank you, Marion,” was all he could manage to say.

Standing slightly behind her, the graying, distinguished-looking William Randolph Hearst stepped forward and extended his hand.

“Happy birthday, Tom. Welcome aboard the Oneida,” Hearst said, smiling and shaking the visitor’s hand with a confident, firm grip.

“Thank you, W.R,” Ince replied, formally addressing the much older man, who most of his other friends called Willie or Bill. Or “Pops,” as only Marion called him. “Sorry for the delay but, you know, they released my latest picture yesterday in L.A. and I had to be there for the premiere.”

“We understand, Tom,” Hearst answered, still smiling pleasantly. “Business before pleasure. That’s what I always say.”

“Thanks for being so understanding, W.R. I got down here as quickly as I could, on the last train leaving L.A.”

“Better late than never, Tom. We’re just starting on our little jaunt. You haven’t missed much so far. We’re going to sail her clear on down to Mexico. Ensenada, I believe. Or maybe Tijuana. I don’t know; I’d have to check with the captain.”

“That sounds like fun. I’m looking forward to it,” Ince said.

“The gang’s all here, Tom,” Hearst said, looping his arm lightly around Ince’s shoulders. “Chaplin, Aileen Pringle, Seena Owen, Julanna Johnston, and a few other movie people. Elinor Glyn … you know … that steamy British romance writer. I’ve even got my movie reviewer from New York, Lolly Parsons, onboard with us.

“Great! I’d love to meet her, W.R,” Ince replied with carefully suppressed excitement. “Maybe she can help me promote the picture we premiered yesterday, The Mirage.”

“Come on down to my cabin and I’ll introduce you to her. I’m sure she’d love to chat with you about your long and distinguished film production career. And we’ve got plenty of imported French champagne on ice, too. In your honor, birthday boy.”

A look of concern spread across Ince’s normally serious face.

“W.R, are you sure you’re okay having booze on board?” Ince questioned worriedly. “The Feds have been cracking down hard on Prohibition violations lately, you know. They’ve been boarding private boats off the coast and searching them.”

Hearst laughed and, as if right on cue, Marion giggled along with him. “Don’t worry, Tom. I’m no bootlegger and these guys know it. I’ve got them bought and paid for. I’m too powerful for them to lay a hand on me, and if they do I’ll ruin them. They’ll quickly find out what it’s like to be unemployed for the rest of their lives. Let’s go drink a toast to the birthday boy. How old are you now, Tom?”

“Forty-three. And, W.R, can we discuss that deal we were talking about earlier? About you renting part of my studio in Culver for Marion’s next pictures?”

Hearst chuckled again and squeezed Ince around the shoulders. “Come on, Tom. Ease up. We’re not on location right now. Loosen your tie, for God’s sake, and relax. There will be plenty of time to talk business later. After the cruise. As Marion here can tell you, I don’t like mixing business with pleasure. For now, let’s just relax and have a good time. We’ll talk business later, okay?”

“Okay, W.R. Thanks,” Ince replied with resignation in his soft voice, as Hearst and Marion both put their arms on his shoulders.

As the three of them made their way toward the lower deck, little did Thomas Ince know that the yacht he had just boarded would be sailing that night. Sailing straight into a fog bank of mystery, intrigue, and controversy that continues to this day — more than 80 years later.

Was the scene that greeted Thomas Ince on the deck of the Oneida on November 15, 1924 really the way it was described above? In all likelihood, it was something similar to that but, the truth is, we will never know. All of the players in the drama that would unfold that night are dead. Whatever they saw or heard in the hours that followed were secrets they took to the grave with them.

In their 2002 movie, The Cat’s Meow, acclaimed director Peter Bogdanovich and screenwriter Steven Peros paint a lurid picture of a wild night of orgies, drunkenness and debauchery that was fairly typical among the unbridled Hollywood cabal and their wealthy private sector collaborators during that era. Guests onboard the Oneida that night are shown to be self-absorbed in their own decadent pleasures while furthering their own career ambitions, playing the game by its then-established rules. But living wildly and recklessly also meant living dangerously. And that night, the line between them was crossed and an innocent man who was unknowingly in harm’s way paid the price.

In The Cat’s Meow, Peros and Bogdanovich leave no room for doubt in the audience’s mind as to who did what and why. They show Hearst (played convincingly by Edward Herrmann) storming around his floating pleasure palace in a blind rage, diamond-studded revolver in hand, seeking the villain who deflowered his beloved Maid Marion, literally right under his nose — in the cabin directly below his. They show him shooting Ince from behind in a tragic case of mistaken identity, while the real “villain” goes merrily sauntering off into the sunset at the end of the piece. And they show a conspiracy of gargantuan proportions; a conspiracy of silence. A cover-up as massive and far-reaching as only one of the world’s richest and most powerful men could successfully pull off.

What really happened that night? Did Hearst actually shoot Ince, thinking it was the notoriously libertine Chaplin putting the make on Marion Davies or was it — as was widely reported in the Hearst-owned publications — a case of death from natural causes? Ulcers and “acute indigestion” rather than a bullet? The truth will never be known. William Randolph Hearst made sure of that.

Who were the players in this Greek melodrama? What brought them together that night? What was the sequence of events that led up to this tragedy? Who did what to whom? Who saw what? Why wasn’t the incident more thoroughly investigated? Who was paid off and with what promises? More questions than answers prevail. More heat than light. Life in Tinsel Town, went gaily on, just as it did before, with one less of its movers and shakers moving and shaking.

MOVIE PRODUCER SHOT ON HEARST YACHT screamed the headline in the morning edition of the Los Angeles Times on November 16, 1924. However, by the time the afternoon edition of the paper hit the streets, the Category 5 hurricane churned up by the early edition had been swiftly downgraded to a tropical depression. Later editions reported that Thomas Ince was taken off the boat with a case of acute indigestion and was sent home to be with his family, where he died two days later.

What was it that changed the story so radically? Was the early edition premature and misinformed? Perhaps, but credible accounts appear to suggest otherwise. What very likely happened was that a powerful man exerted his considerable influence over the media.

Even though the Los Angeles Times was not one of those owned by Hearst, so mighty was the clout he wielded that even rival newspapers dared not cross him. No further stories appeared in any newspapers that week that even hinted of foul play.

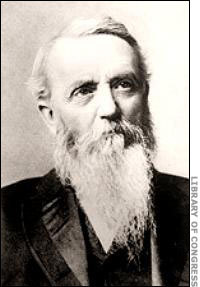

Who was William Randolph Hearst and how did he get so powerful? The classic rags to riches story belonged not to him but to his father, George Hearst. The elder Hearst, who started out in life with nothing, became a multimillionaire mine owner and rancher. His silver mines in Nevada’s legendary Comstock Lode were estimated to be worth about $400 million long before the turn of the 20th century.

William Randolph Hearst was born on April 29, 1863, in San Francisco, the only child and heir of George Hearst and Phoebe Apperson Hearst, who doted notoriously on her son. In 1887, at age 23, W.R. became proprietor of the San Francisco Examiner which his father accepted as payment for a gambling debt. In Citizen Kane, Kane takes over ownership of a fictitious San Francisco newspaper almost as a lark; something he thinks will be fun to do. In real life, the situation was not much different. When Hearst took over the Examiner, it was more from a sense of adventure than one based on work experience.

Hearst quickly turned the flagging newspaper’s fortunes around by running sensational stories designed more to titillate than inform. He was one of the pioneers of banner headlines and he used them to maximum effectiveness; the larger and bolder the better. Hearst turned the Examiner into a combination of reformist investigative reporting and lurid sensationalism. He also hired some of the best journalists available, including Ambrose Bierce, Stephen Crane, Mark Twain, and Jack London.

In 1895 he acquired the New York Morning Journal and launched the Evening Journal the following year. Going head-to-head with another publishing titan at the time, Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World, Hearst dueled his rival with ever more sensationalist stories that inflamed raw emotions in readers more than informing them based on facts. Many of these stories were accompanied by lavish illustrations (before the development of news photography) that greatly exaggerated the stories they accompanied. By the turn of the century, with several more newspaper acquisitions in major American cities under his belt, he was a force to be reckoned with. The emperor of a publishing empire stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. His national chain of newspapers and periodicals grew to include the Chicago Examiner, Boston American, Cosmopolitan, and Harper’s Bazaar.

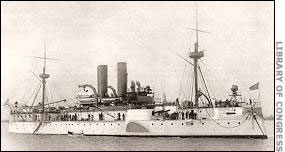

The term “yellow journalism,” which is frequently heard today when a newspaper overly sensationalizes a story, has its roots in the Pulitzer and Hearst chains of publications and their notorious turf battles of the 1890s. Originally named after a cartoon character, The Yellow Kid (which ran in the newspapers of both men), it became especially synonymous with Hearst. A strong proponent of American colonial expansion to compete with the colonial powers of Western Europe, Hearst set his sights on Cuba which was then under Spanish rule, using the power of the press to drum up support for American military adventurism there.

One of the last remaining outposts of Spain’s once-vast colonial empire in the Western Hemisphere, Cuba, with its rich natural resources, was portrayed in the Hearst newspapers as a land of noble peasants suffering harsh, inhuman persecution under the thumb of a cruel mother country. He even went so far as to portray a well-treated female prisoner in a Cuban jail as a brave, brutalized, innocent martyr to the cause of her island colony’s freedom; a victim of barbaric Spanish atrocities rivaling those committed during the Inquisition.

Hearst’s Journal trumpeted the supposed plight of 18-year-old Evangelina Cisneros, calling her a “Cuban Joan of Arc” and asserting that she bravely protected her “virtue” from her lecherous Spanish jailers. He circulated petitions nationwide demanding her release. Among those signing the petition were the mother of President William McKinley, American Red Cross founder Clara Barton, patriotic songwriter Julia Ward Howe, and the widows of Jefferson Davis and Ulysses S. Grant. When diplomatic channels failed to secure Cisneros’ release, Hearst hired a notorious adventurer to spring her from jail, which he likely did by simply bribing the guards, despite sensationalized stories of a dramatic and daring jailbreak escape. Then Hearst bragged it up in huge headlines, saying that his newspaper accomplished “at a single stroke what the red tape diplomacy had failed to bring about in many months.”

Cisneros was given a heroine’s reception in New York and an invitation to meet with President McKinley at the White House. All the while, Hearst remained deaf to widely circulated reports questioning Cisneros’ supposedly virtuous reputation and other reports that the jailbreak story was a hoax. Some credible accounts even portrayed Cisneros as a scheming temptress who used her femininity to nearly lure one of her jailers to his death. None of this mattered to Hearst. All that mattered was that he got his exclusive story and the P.R. (and increased circulation) that went with it.

In yet another instance of lurid and deliberately misleading sensationalism, the Journal reported that three American women departing Cuba were stripped naked, searched and groped by lecherous Spanish soldiers. The story was accompanied by a graphic illustration of a naked woman and sinister-looking soldiers leering at her. The truth, as the women themselves told it on their arrival back in America, was that they were searched by women in privacy, with male soldiers outside the room.

In the late 1890s Hearst sent renowned artist and illustrator Frederic Remington to Cuba to report on developments there. After a lengthy stay, Remington reported that Havana was quiet and peaceful and that there was no war going on. But, when Remington requested a return to the U.S., Hearst’s response was reported to be, “Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.”

The opportunity to “furnish” that war came on February 15, 1898, when the American battleship Maine mysteriously exploded in Havana Harbor, killing over 200 American sailors. Although sabotage was never proven, the Hearst newspapers insisted it was and they called for war against Spain. In reporting the Maine incident, Hearst ordered all other stories off the front page, exploiting the tragedy with huge headlines and splashy illustrations of the ship exploding. The Spanish-American War began soon afterward and, by its end, Hearst’s American dream of a global colonial empire was a reality.

As the 20th century arrived and Hearst was continuing his string of newspaper and magazine acquisitions, he was also becoming a political force. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1903 to 1907, even though he rarely showed up for Congressional sessions and was proud of not doing so. On those occasions when he did, he could be brutal. Speaking on the House floor, he once accused a colleague who had attacked him of sanctioning a murder at a bar he owned in the Boston area. It was soon learned that the bar was owned by the congressman’s father and the death Hearst accused his colleague of sanctioning had been ruled an accident. As many had witnessed from his years of waving the bloody shirt on behalf of Cuban rebels and other causes, Hearst was never shy about stretching the truth. Or abusing the information gathered by his reporters.

Hearst unsuccessfully sought the presidential nomination as a Democrat in 1900 and 1904, the mayor’s office in New York City in 1905, and the governor’s office of New York State in 1906. His gubernatorial defeat to Charles Evans Hughes put an end to his political aspirations and he left the U.S. House the following year.

Always at the center of controversy, Hearst took a lot of heat when two of his writers, in separate pieces, hinted that President McKinley should be assassinated. When that actually happened in September 1901, many people blamed Hearst, despite the fact that the convicted assassin never read any of the Hearst newspapers.

In 1903, Hearst married Millicent Willson, a theatrical performer, in New York City. The couple had five sons: George, William Randolph Jr., John, and twins Randolph and David, most of whom also went into some phase of the business.

Early in his career Hearst and his newspapers championed the causes of the “little guys,” often siding with the common folk on a wide range of social issues. In typical Hearst fashion, stories were often sensationalized as they portrayed the plight of those living in poverty and other hardships. Many of the issues on which he took sides later became law, such as anti-trust legislation, tax reform, and the direct election of U.S. Senators. He also took on the powerful New York County Democratic political organization better known as Tammany Hall and had many high-profile verbal scuffles with its influential leaders.

However, as he got older, his views and those of his publications took on a more conservative bent. He became a rabid foe of organized labor, which had unionized most of his newspaper operations, thanks to favorable labor laws passed during the FDR administration. He also blasted socialism, and communism, but not the fascism coming to the fore in Italy and Germany in the 1930s. He even had meetings with Hitler and Mussolini and appeared to condone what they did in their early political careers, despite his protestations that he wasn’t anti-Semitic.

Hearst was a notorious xenophobe. He reportedly hated minorities, and he used his chain of newspapers to aggravate racial tensions at every opportunity. He especially hated Mexicans, portraying them as lazy, degenerate, and violent, and as marijuana smokers and job stealers. However, the real motive behind this prejudice may well have been that Hearst had lost 800,000 acres of prime timberland to the rebel Pancho Villa, suggesting that Hearst’s racism was fueled by Mexican threats to his empire’s source of newsprint.

In the 1920s Hearst began building his massive castle-like estate at San Simeon, overlooking the Pacific Ocean near California’s Big Sur Country. La Cuesta Encantada (“The Enchanted Hill”), which Hearst family members simply referred to as “the ranch,” took nearly 28 years to build. It had 165 rooms, many of which contained priceless artworks and furnishings, and the grounds boasted numerous ancient sculptures taken from European archeological sites. “The Ranch” also boasted a private zoo, golf course, stables, and numerous riding trails. Some early reports exaggerated that the Hearst-owned property around San Simeon was “half the size of Rhode Island.” Although that wasn’t actually the case, 240,000 acres (375 square miles) in the hands of one man is still a sizable piece of real estate.

With party-girl Davies often acting as gracious hostess, San Simeon became one of Hollywood’s favorite get-away-from-it-all hot spots. Among the frequent guests were Carole Lombard, Mary Pickford, Sonja Henie, Dolores Del Rio, Louis B. Mayer, and many other visiting celebs like Charles Lindbergh and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York City. An invitation to the estate and its functions was a highly sought after badge of honor among the Hollywood elite.

Though his marriage was reported to be a happy, fulfilling one with five healthy children, like most men with wealth and power, Hearst had a roving eye. In 1915 that 52-year-old eye fell on a lively, blonde-haired, 18-year-old dancer from the Ziegfeld Follies named Marion Davies.

Marion Davies was born Marion Cecilia Douras in Brooklyn, New York on January 3, 1897. She reportedly picked up her stage name after walking past a building named for the Davies Insurance Company in New York, and she liked the sound of it. Her whole family must have liked it, too. They all took on the name, including her sisters, Rose, Reine, and Ethel who also went into acting careers.

Marion appeared in a number of musicals during the silent era and had been in the Ziegfeld company when she first caught Hearst’s eye in December 1915. She was prominently featured in a musical called Stop! Look! Listen! at New York’s Globe Theatre. Hearst was in a second-row seat with another publisher friend who, it is believed, had been dating Marion. After she and Hearst became involved, he showered her with expensive gifts, but the best gift he gave her was a long career in show biz and in the public eye.

During the course of their lengthy affair, the bubbly, sprightly, fun-loving Marion was the balloon that lifted the spirits of the businesslike, strait-laced newspaper tycoon who was old enough to be her grandfather. Their age difference, according to many accounts, seemed to bring out the oft-buried fun side in him. Among other things, Marion delighted in masquerade parties and she encouraged “Pops” to participate, which he did. In one scene in The Cat’s Meow, Hearst has on a jester’s costume, which isn’t stretching the truth too far. A number of photographs of Hearst in variously humorous costumed garb have been widely circulated over the years.

Hearst’s affair with Marion was, unlike most other extra-marital affairs of that time, an almost-open book. The two appeared in public frequently, with her hanging onto his arm. But, in true chivalrous fashion, he tried to shield Marion from negative publicity as much as possible by simply not reporting on it. Neither did the rival publications. Hearst was just too powerful an adversary to risk antagonizing. Anyone else would have been fair game, but not him. Reporters and editors of competing publications never knew when the day might come that they would seek a job with a Hearst-owned publication. Or be offered one at a higher salary if they hadn’t previously offended him.

Millicent was understandably not happy with her husband’s philandering but she said nothing publicly about it, either. Hearst’s mega-millions, which enabled her and their children to live like royalty, bought more than 35 years of silence from her. Some reports said he was considering divorce but was dissuaded from doing so by Millicent’s potentially high demands for a settlement and the scandal it would cause. Nonetheless, by 1925, the Hearsts were no longer living together. Millicent spent most of her time in New York busying herself with high society functions and charitable causes, while Willie ensconced himself comfortably in California with his mistress.

Amazingly, despite his wealth and power, Hearst had no other romantic involvements that anyone knows about. For three and a half decades, he was steadfastly and singularly faithful to Marion, even while being unfaithful to his legal wife. And even while Marion was probably unfaithful to him.

Of course, when Hearst learned of Marion’s aspirations to become a star, no expense was spared to make that happen. She became the star of a production company set up just for her: Cosmopolitan Productions. “For the greater glory of Marion Davies — a vanity operation if ever there was one,” according to Kenneth Anger in his book, Hollywood Babylon. Despite a noticeable stutter, this speech impediment had no effect on Marion’s early film career, since no one had to listen to her. “Talkies” wouldn’t come along until the late ’20s/early ’30s.

In Citizen Kane, after his second wife, Susan Alexander, confides a desire to be a professional singer, Kane builds a million-dollar opera house in Chicago, primarily to showcase her. However, she proves to be a flop and she gets bombed by the critics. In real life, Davies got rave reviews for her movies but, of course, those were written by paid cheerleaders at the Hearst papers. Among her fawning fans was none other than Louella Parsons, who was comfortably lodged on Hearst’s payroll with a lifetime contract.

Outside the tightly controlled loop, though, Davies’ performance grades were not so hot. By most objective accounts, both contemporary and later, Marion was not a particularly good actress. She was just another pretty face; one among many in the film industry. Because of her bubbly personality, she was better suited to comedy roles, but Hearst preferred her in dignified, dramatic parts, and he guided her career in that direction, much to her dismay at times. As well as the dismay of critics and moviegoers.

Even Marion, herself, reportedly recognized her own shortcomings talent-wise. One of her most famous quotes was, “With me it was 5 per cent talent and 95 per cent publicity.”

In later years, faced with bankruptcy during the Depression, Hearst’s empire was reportedly saved by Marion selling off between $1 and $2 million of the jewelry and gifts he had lavished upon her over the years. Less than a year after Hearst’s death in 1951, Marion was married for the first and only time to a former NYC policeman and part-time actor named Horace Brown. The marriage was reportedly not a happy one but they stayed together until her death from jaw cancer in 1961.

Known as the “Father of the Western,” Thomas Ince was one of Hollywood’s earliest wunderkinds. His output between 1911 and 1923 was nothing short of prodigious. In 1912 alone he directed 29 pictures, topping his total of 24 from the year before. Even though most movies made during the silent film era were “shorts,” making each one was still a painstaking effort. Lacking today’s modern digital technology and other advantages, everything in those early years had to be done by hand with crude equipment. A 20-minute short feature could take days or weeks to shoot and just as long to edit into a final cut. In all, Ince was credited with directing nearly 80 movies in a career spanning only a decade and a half: an output that, by any standard, easily dwarfs everyone else who followed his footsteps into the film production business.

Ince is also widely considered to be the founder of Hollywood’s “studio system.” Among his many innovations was his ability to shoot multiple pictures simultaneously on different sets. In The Cat’s Meow, Marion Davies (played by Kirsten Dunst) toasts Ince (played by Cary Elwes) as “the man who figured out how to make ten pictures at once,” to which Hearst sarcastically retorts, “And he takes credit for all of them.” Such was Ince’s ability to inspire both high praise and jealousy among his peers in the industry.

Among the other innovations he was credited with are the usage of a detailed “shooting script,” which also contained information on who was in the scene, and the “scene plot,” which listed all interiors and exteriors, and cost control plans. He helped create a standardized and mechanized mode of production similar to the assembly lines that were becoming standard practice in other industries. He also was one of the first who employed a separate writer, director and editor, instead of doing everything himself.

Thomas Harper Ince was born onNovember 6, 1882 in Newport, Rhode Island. In a short but stellar career he was a silent film actor, director, producer and screenwriter. He was literally “born into the business,” coming from a family of stage actors. He first appeared on the stage at age six and then worked with a number of stock companies. He made his Broadway debut when he was 15 and found sporadic work invaudeville. Discouraged with the stage, he headed to California in 1911, and turned to film.

In his early days in Southern California, he understudied with several well-established producers, including Carl Laemmle, before launching out on his own. Many of his early pictures were Westerns and historical dramas, which employed innovative filming techniques other producers would later copy. To accommodate the many productions he was juggling, Ince had built a city of motion picture “sets” on a stretch of land in Santa Monica called “Inceville.” Here he was able to shoot many of the outdoor locales needed for his films. Inceville soon became a mecca for hopeful actors and actresses eager to enter the movie business. A number of filmdom’s earliest stars, including William S. Hart and Olive Thomas, did some of their first film work there.

Ince married Eleanor “Nell” Kershaw in October 1907 and they had two sons, both of whom entered the film business. Richard Ince became an actor and Thomas H. Ince, Jr. was a writer.

In 1915, Ince partnered with D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett to create the Triangle Motion Picture Company, and three years later he founded the studios in Culver City that would later house MGM. Film and television history would be made on that lot long after Ince’s death, with such classics as Gone with the Wind, King Kong, The Untouchables, Lassie, Batman and — ironically — Citizen Kane. Later, along with industry giant Adolf Zukor, Ince became one of the founders of Paramount Pictures.

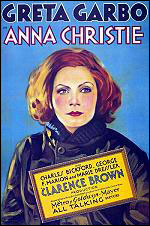

After 1916 Ince’s output as a director dropped markedly as he began focusing more on producing and the business aspects of the blossoming film industry. One of his last full-length films, Eugene O’Neill’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Anna Christie, is considered a classic of the silent film era. (Its 1930 remake also created a sensation as Greta Garbo’s first role in a “talkie.”)

However, by the time the ’20s roared in, Ince’s star was descending. He was considered old hat. Many of those in the industry who cut their teeth in his Culver City studio early in their careers were venturing out on their own and surpassing him. He was finding less and less of a market for his products and was making fewer pictures. His specialties, shorts and Westerns, were becoming passé (although Westerns would make a comeback in later years, especially after the advent of television). The industry became more focused on stars than on those who made them stars. Its sycophants in the media did likewise, loyally parroting the studios’ official lines.

In The Cat’s Meow, Hearst mocks Ince as “a cripple” in the film business and his cruel assessment wasn’t far off base at that point in Ince’s career. At the time of his death, Ince was widely believed to be verging on bankruptcy. One of his reported purposes for going on the fatal cruise was to try and salvage his sagging fortunes by convincing Hearst to merge his Cosmopolitan Productions with Ince’s Culver City operation. Ince also reportedly wanted to manage Davies’ film career, which would have ensured him of a steady, substantial income from the wealthy newspaper tycoon. However, Hearst was reportedly chilly to both ideas and, in the movie, this comes out in no uncertain terms.

As if to rub salt in the wound, Hearst is walking the yacht’s deck with Ince in one scene, gleefully shooting at seagulls flying nearby. When he kills one and watches its corpse plop into the water, Hearst asks Ince if he’s ever eaten seagull meat, to which Ince disgustedly replies no. “It’s awful!” Hearst says. “Kind of like eating crow.”

In the movie, though shown to be more dignified and straight-up than most of the other guests aboard the Oneida that night, Ince was nobody’s angel, either. He is shown in several steamy bed scenes with Margaret Livingston, a moody, struggling actress whose career he is trying to boost. She was his mistress in real life, too, despite the convincing public façade of his long, supposedly happy marriage to Nell.

In the movie, Margaret boards the yacht on the arm of Ince’s bachelor business manager, George Thomas, to avoid the suspicions of Hollywood’s prying eyes. Neither Ince nor Margaret were rich and powerful enough to cavort as openly as Hearst and Davies did and thumb their noses at the gossipmongers. Ince’s already-floundering ship could have sunk totally if word of his affair ever became common knowledge. He is sufficiently troubled by Hearst’s cutting remarks, which he confides to Margaret. However, he is even more troubled at the prospects of failure to form a merger with Hearst, and most fearful of all of his potentially dismal future in the industry. Speculation at that time and later pegged him as a suicide candidate had he not died when he did.

Just two years before his own death, Ince’s name came up in another mysterious, unsolved Hollywood murder. Renowned Paramount producer William Desmond Taylor was found shot to death in his bungalow on Feburary 1, 1922. Suspected of the murder but never charged was Ince’s former partner, Mack Sennett, who was reported to be Taylor’s competition for the love of star Mabel Normand. Sennett’s alibi to investigators was he had spent that night at Ince’s house. How Ince reacted to the news involving two of his friends and business partners isn’t known but it likely had an impact on his already-fragile state of mind.

The atmosphere aboard the Oneida, despite its surface appearance of frivolity and carefree-ness, was tense and potentially volcanic just beneath the surface. Hearst was certainly not unaware of the rumors surrounding Marion and Chaplin, nor was anyone else. Even though the tabloids treaded lightly (or not at all) on Hearst’s relationship with Marion, what she did with Chaplin in public was fair game. Gossipmongers like Grace Kingsley of the New York Daily News, had a field day clucking about the two of them having been seen together on a number of well-publicized occasions, at least one of which was less than a week before Ince’s death. It was even reported that Chaplin had taken to visiting Marion on the sets of her productions, scampering hastily out back doors when warned of Hearst’s approach by his loyal posted sentinels.

Speculation has it that Hearst invited Chaplin onboard the Oneida that night specifically for the purpose of observing Chaplin’s behavior toward Marion and possibly catching the two of them in the act. What he planned to do if he caught them in flagrante delicto is open to speculation. In The Cat’s Meow, when Chaplin and Marion make love in her cabin, it is reported to be their first time in bed together. In reality, if there had been any hanky-panky between them, that “first time” would likely have occurred sooner.

Over the years before and after the Oneida incident, Chaplin had acquired a well-earned reputation as a ladies’ man. His name, at various times, had been romantically linked to such stars as Edna Purviance, Josephine Dunn, Lila Lee, Pola Negri, Paulette Goddard, and others. Many others! Including some who weren’t stars like wealthy socialite Peggy Hopkins Joyce. As Kenneth Anger points out in Hollywood Babylon, “Chaplin did not seek out scandal. Scandal came to him.”

Chaplin was especially notorious for “robbing the cradle.” His earliest wives and many of his conquests were much younger than him. Some were not even out of their teens. On the night the Oneida set sail he was troubled by an impending shotgun wedding to Lita Grey, who was all of 16 at the time and was carrying Chaplin’s baby.

There were other tensions bubbling beneath the surface of the ill-fated cruise, as well, not the least of which was Ince’s reportedly desperate effort to lure Hearst into a lucrative partnership that would have salvaged Ince’s faltering career. It can be safely speculated that George Thomas’ presence among the guests was to assist Ince in inking the deal, if there was to be one. And, if the movie can be believed, the future of Ince’s relationship with Margaret Livingston may have hinged on forming the partnership with Hearst that would have furthered her acting aspirations.

The movie, if not the real-life scenario, was rife with Shakespearean intrigue. Ince is portrayed as an Iago-like character to Hearst’s Othello: inflaming his jealousy with whisperings of Marion’s dalliances with Chaplin, calculatingly trying to score brownie points with the media mogul and get into his good graces. Whether or not this actually happened is pure speculation. Hearst knew well in advance of the cruise about the rumors and he certainly wouldn’t have needed any prompting to investigate further.

Among the other guests on that cruise were steamy British novelist Elinor Glyn (from whose perspective, the movie is told); aspiring actresses Seena Owen, Aileen Pringle, Jacqueline Logan, and Julanne Johnston; Dr. Daniel Carson Goodman, a licensed but non-practicing physician who was Hearst’s production head at Cosmopolitan; Joseph Willicombe, Hearst’s chief secretary and go-fer; Hearst chain publisher Frank Barham and his wife; Davies’ sisters Ethel and Reine; Davies’ niece Pepi; and black members of an unnamed jazz band.

According to Anger’s account, Davies was picked up on the set of her latest picture, Zander the Great, by Chaplin and Parsons, and the three of them drove down together to the yacht in San Pedro. Ince, who was screening his latest picture in Los Angeles, took a train and met the boat in San Diego a day or so later. Onboard, along with the celebrity passengers, was an ample supply of illegal champagne and, if the movie is to be believed, marijuana. Like participants in a Roman orgy, the debauchery was nonstop into the wee hours of the morning. Then, just as the real fun was getting started, it came to a grinding halt.

In his comprehensive, nearly 700-page book on Hearst, entitled simply The Chief (including over 50 pages of footnotes), author David Nasaw makes scant and only cursory reference to the circumstances surrounding Ince’s death. He glosses over the incident and devotes barely a page and a half to something that, alone, should have been worthy of at least an entire chapter. Writing in 1999 for the book which was published the following year, Nasaw asserted, “Today, seventy-five years after Ince’s death, there is still no credible evidence that he was murdered or that Hearst was involved in any foul play.”

In giving credence to the widely circulated story of Ince’s death from natural causes — acute indigestion, heart attack, or whatever — Nasaw may have meekly and compliantly allowed himself to be co-opted by the still-powerful Hearst family interests. It needs to be noted that, when the private papers of William Randolph Hearst were finally opened to public scrutiny in the 1990s, Nasaw was the first writer who was granted access to them. And that access didn’t come easy for him. According to a story in the Albany (NY) Times-Union (a Hearst newspaper), it came after four years of protracted negotiations with the Hearst family. It appears safe to speculate that not saying anything bad about “Pops” might have been a pre-condition for Nasaw being awarded first crack at those papers.

It’s worth noting, also, that Nasaw positions himself as an apologist for Hearst on other occasions in the book. Most notable among them is his weak and unconvincing attempt to explain what Hearst’s rationale was for his reported directive to Frederic Remington on the eve of the Spanish-American War: the one in which he allegedly told Remington, “You furnish the pictures. I’ll furnish the war.”

According to Nasaw’s interpretation, “Hearst might well have written the telegram to Remington, but if he did, the war he was referring to was the one already being fought between the Cuban revolutionaries and the Spanish army, not the one the Americans would later fight.” The historical record conclusively establishes that Hearst was trying to goad the U.S. into declaring war on Spain, and Remington himself — who was there in Havana at the time — had reported that there was no “war” going on between the Cuban rebels and the Spaniards. What other conclusion is it possible to draw from the tone of Hearst’s ultimatum? Headlines like “NOW TO AVENGE THE MAINE!” and “HOW DO YOU LIKE THE JOURNAL‘S WAR?” would appear to speak for themselves.

(A further note: Nasaw writes that the first Cuban rebellion against Spanish rule took place in 1868 when it is a matter of historical fact that Narciso Lopez led two expeditions to Cuba in the early 1850s that attempted to throw off Spain’s rule.)

Nasaw goes on to say that, after Ince’s death, “Stories began to percolate through Hollywood that Hearst, in a fit of jealous rage, had murdered Ince. The absence of hard evidence made it easier to invent new rumors. In the years to come, Hearst would be accused of poisoning Ince, shooting him, hiring an assassin to shoot him, fatally wounding him while shooting at Chaplin — and, most recently and ridiculously, in an article published in 1997 in Vanity Fair, of accidentally stabbing him through the heart with Marion’s hatpin, causing an instant, fatal heart attack.” Nasaw appears to conclusively discount all of these possibilities, preferring instead to parrot the Hearst party line that attributed “natural causes” to Ince’s death.

“While it was true that Hearst had done his best to keep Ince’s presence on the Oneida a secret, he had done so not to cover up a murder, but because he didn’t want the press or the local police investigating his yachting party with champagne flowing in flagrant disregard of the Prohibition laws,” Nasaw further rationalizes.

It has been reported in other sources, and in The Cat’s Meow (which Nasaw blasts in uncompromising terms, despite admitting to not having seen the movie), that Hearst was also trying to cover for Ince who was cavorting onboard with his mistress. In the movie, Hearst calls up Nell Ince and tells her about her husband’s infidelity, strongly implying that her silence on the entire affair would be in everyone’s best interests. Especially Hearst’s. What better way to ensure a grieving widow’s cooperation in averting an inquest than to implicate her late husband in a potentially embarrassing extramarital affair?

Whether or not Hearst attempted to whitewash a murder he may have committed and swear everyone who had been onboard to silence, will probably never be known for certain. Too much time has passed and the trail has long since gone cold. However, there are many elements to the story that strongly suggest a massive cover-up operation was orchestrated by Hearst. Not the least of these elements was the decision to have Ince’s body cremated almost immediately, before an official inquest could be launched. Hearst provided Nell Ince with a sizable pension after her husband’s death, and she left for Europe soon afterward, possibly on Hearst’s advice to avoid media scrutiny.

Immediately after the Ince tragedy, others onboard the Oneida that night began denying that they were there, including Chaplin and Parsons, despite witnesses who vouched to the contrary. Parsons insisted that she was in New York at the time. However, her assertion didn’t stand up to the word of several passengers who reported seeing her on the yacht, and another credible witness who said she saw Parsons with Davies and Chaplin at the studio, prior to departure. Parsons, it is widely believed, may have witnessed the actual shooting and was rewarded for her silence. Many believe that it was no coincidence “Lolly” was awarded a lifetime contract for her syndicated column from Hearst immediately after Ince’s death. Access to 600 publications and 20 million readers has the potential to buy a lifetime’s worth of silence.

Chaplin’s version of the story is as laughable as some of his early movies. Not only does he deny being on the Oneida that weekend, he also insisted that he, Hearst, and Davies visited the ailing Ince later that week. He further stated that Ince died two weeks after their visit. In reality, Ince was taken off the boat early on a Sunday morning and was dead within 48 hours. Chaplin, himself, attended the memorial services for Ince that Friday. Convenient memory lapse? Perhaps.

Casting further doubt on Chaplin’s alibi is the observation reportedly made by his own secretary and driver, a Japanese man named Toraichi Kono. Kono reported seeing Ince being taken off the boat in San Diego with a bullet wound in his head. Hearst was known to carry a diamond-studded revolver on the boat, with which he allegedly delighted in shooting down seagulls. Apologists who insist that Hearst’s gentle personality would have rendered him incapable of shooting another human being might have a difficult time reconciling that assertion with his flagrant disregard for peaceful avian creatures flying over their natural habitats.

Kono’s story went nowhere, leaving unanswered the question, why was he there if Chaplin wasn’t?

Davies was also in the denial mode. She never acknowledged that Chaplin, Goodman, or Parsons were on board the yacht that weekend. She also reportedly insisted that Nell Ince called her late Monday afternoon at United Studios to inform her of Ince’s death. Highly unlikely since he didn’t die until Tuesday.

And how does one explain the early Los Angeles Times story reporting that a producer had been shot on Hearst’s yacht? Nasaw makes no mention of this at all. Nor does he mention that the first disclosure spun by Hearst was that Ince was stricken while visiting San Simeon, more than 300 miles away.

What is known is that Ince was driven home to his Spanish-style mansion in Benedict Canyon, suffering from whatever it was — a gunshot wound or acute indigestion — and he died there two days later. Dr. Ida Glasgow, Ince’s personal physician, signed the death certificate citing heart failure as the cause of death. Davies, Chaplin, and other celebs attended the funeral on November 21, but Hearst was conspicuously absent, preferring to retreat to his “ranch” and steer clear of the spotlight.

If Hearst had thought that, by cremating Ince’s body, he had immaculately solved his dilemma, he wasn’t quite out of the woods yet. Rumors of foul play were just too strong and widespread to be ignored. Few if any people believed that Hearst had shot Ince deliberately, having had no solid basis for doing so. The most commonly circulated stories — and the most plausible theories — were that Chaplin was the intended target and Ince just happened to be in the way or in the wrong place at the wrong time when the fatal bullet was fired.

In The Cat’s Meow, Chaplin had left Marion minutes before Hearst, storming around in a blind rage, spied Marion sitting on a step talking to Ince who was sitting next to her. Because he was wearing the same type of hat Chaplin often wore, Hearst mistook Ince for his nemesis and fired a single shot that struck Ince in the head. Once he realized his fatal mistake, Hearst began scrambling around frantically to cover up his misdeed.

Did it actually happen this way? No one alive today knows but it is entirely possible. There are many theories. Some speculate that Chaplin and Ince were together when confronted by Hearst, and Ince, attempting to be the peacemaker, may have gotten in the way when Hearst pulled the trigger. Or there may have been a struggle for the gun and it misfired, hitting Ince in the head. Or Hearst may have fired several shots at Chaplin who was fleeing Marion’s cabin after being caught in bed with her, and a stray shot felled Ince who had been nearby. Each of these scenarios is entirely possible. One suggested scenario that is less likely is that a shot fired by Hearst might have penetrated a floorboard and killed Ince in his cabin.

No formal inquest or anything even remotely resembling one by the standards of the time was ever held. Cremating Ince’s body within days of his death decisively precluded that possibility. Forensic science as we know it today barely existed in 1924, if it existed at all. Earlier that year, a 29-year-old J. Edgar Hoover had just taken over a disorganized, barely functional, fledgling federal investigating agency that would later become known and respected as the FBI. An autopsy at that time, at best, would have only yielded basic information about a probable cause of death. Nonetheless, even the most cursory examination of Ince’s body — had one been held — would have been able to tell the difference between a bullet wound and a malfunctioning digestive or coronary system.

The rumors of foul play, being too strong to ignore, finally prompted San Diego District Attorney Chester Kemply to launch an investigation. However, that “investigation” was a sham.

Despite the presence of 15 to 20 guests aboard the Oneida that night, Kemply chose to call only a single witness — Dr. Goodman, who had treated Ince and helped get him off the boat after he was either shot or stricken with indigestion. Part of the transcript of Goodman’s testimony is as follows:

” …When he (Ince) arrived on board he complained of nothing but being tired. Ince discussed during the day details of his agreement just made with (Hearst’s) International Film Corporation to produce pictures in combination. Ince seemed well. He ate a hearty dinner, retired early. Next morning he and I arose early before any of the other guests to return to Los Angeles. Ince complained that during the night he had had an attack of indigestion, and still felt bad. On the way to the station he complained of a pain in the heart. We boarded the train, but at Del Mar a heart attack came upon him. I thought it best to take him off the train, insist upon his resting in a hotel. I telephoned Mrs. Ince that her husband was not feeling well. I called in a physician and remained myself until the afternoon, when I continued on to Los Angeles.

“Mr. Ince told me that he had had similar attacks before, but that they had not amounted to anything. Mr. Ince gave no evidence of having had any liquor of any kind. My knowledge as a physician enabled me to diagnose the case as one of acute indigestion.”

Incredibly, D.A. Kemply ended his investigation without questioning any other potential witnesses. He dismissed the case with these words:

“I began this investigation because of many rumors brought to my office regarding the case, and have considered them until today in order to definitely dispose of them. There will be no further investigation of stories of drinking on board the yacht. If there are to be, then they will have to be in Los Angeles County where presumably the liquor was secured. People interested in Ince’s sudden death have continued to come to me with persistent reports and in order to satisfy them I did conduct an investigation. But after questioning the doctor and nurse who attended Mr. Ince at Del Mar I am satisfied his death was from ordinary causes.”

Case closed.

Marion Davies outlived the much older Hearst by only ten years. She was not allowed to attend his funeral and was persona non grata among the surviving Hearst family members after that. Initially claiming that Hearst had left most of his estate to her, she was later forced to back down from her claims by California community property laws that favored Millicent and the five Hearst sons. Instead of fighting, Davies meekly yielded millions of dollars for the sum of only one dollar.

Orson Welles died in 1985 at the age of 70. The general consensus among film historians is that he peaked early with the making of Citizen Kane and produced little of any significance after that. For many years he was a favorite guest on talk shows and is best remembered by the present generation for his TV commercials in which he says, “Paul Masson will sell no wine before its time.” Ironically, Welles and Hearst only met once, and little was said between them. It was in an elevator in a building in San Francisco where the film was apparently being premiered. Welles offered Hearst some free tickets but the tycoon declined to answer. Welles later stated that if the same person had been Charles Foster Kane instead of Hearst, he would have probably accepted the offer.

In addition to The Cat’s Meow, there was another movie about Davies and her relationship with Hearst, this one made for TV. The Hearst and Davies Affair, which aired in 1985, starred Robert Mitchum as Hearst, Virginia Madsen as Davies, and Kimble Hall as Ince.

Charlie Chaplin, after another two decades of scandals, paternity suits, legal troubles, and other unfavorable publicity, finally decided he’d had enough. On June 16, 1943, at the age of 54, he settled down, married 18-year-old Oona O’Neill (daughter of the famous playwright, Eugene O’Neill), and basically dropped out of the Hollywood scene. He and Oona spent most of their long marriage together in Vevey, Switzerland, along the shore of Lake Geneva, raising the eight children they had together. He died there on Christmas Day 1977, widely heralded as an iconic figure in motion picture history.

Ince’s widow, Nell, never remarried and spent many years after his death as a recluse. The pension Hearst provided for her was wiped out during the Depression and, later in her life she was either a taxi driver or a taxi dancer; the accounts can’t seem to agree which one it was. More than likely it was the former, since taxi dancers were generally young and attractive, something Nell Ince wouldn’t have been by that time. She died in 1971 at the age of 86.

Simeon

The Ince mystery yielded some bizarre spinoffs. In one such story, Abigail Kinsolving, Davies’ secretary, told police she had been raped by Ince on the boat and had allegedly been seen by other guests to have bruises on her. Her story is rendered highly implausible by the fact that Margaret Livingston was on the same cruise. It’s not likely the normally cautious Ince would have taken such a risk within the narrow, gossipy confines of a 280-foot yacht. Several months later Kinsolving gave birth to a daughter out of wedlock and, soon after that, she was found dead under mysterious circumstances on the grounds of San Simeon. Her baby girl was sent to an orphanage and supported by funds Davies provided.

At the Culver City studios Ince founded, several reports have surfaced about his ghost having been seen on the premises. In one such incident, in 1988, a workman doing renovations was reportedly confronted by an apparition that angrily stated, “I don’t like what you’re doing to my studio!” before vanishing into the wall. The description of the ghost appeared to fit that of Thomas Ince.

A number of other books have been written about Hearst over the years, some lightly touching on the Ince incident without making value judgments or speculating on probable cause. Others don’t mention it at all. One of the more interesting books to cover the topic was a 1996 work of fiction — “based on fact,” of course. It is titled Murder at San Simeon and it names the players in the Ince drama by name, even while contorting the storyline. The principal author is Patricia Campbell Hearst, better known to the world as “Patty.” Daughter of Randolph Hearst and granddaughter of W.R., she made headlines in the mid-1970s with her “kidnapping” and subsequent crime spree exploits with the Symbionese Liberation Army.

Today, the fabulous Hearst estate at San Simeon is a major tourist attraction along the highway through California’s Big Sur country. It was so huge and unwieldy that Hearst, in his dying days, realized that no one individual could ever manage it again and he donated it to the State of California as a historical site.

Although the mystery surrounding Ince has never been solved, in the minds of those who were inclined to believe the worst at the time, there was no room for doubt. How else to explain the nickname given to the Oneida shortly afterward: “William Randolph’s Hearse.”