Natural Born Killers movie spawns copycats & lawsuits — the Crime Library — Background — Crime Library

Killers

In the 215 years since the First Amendment to the Bill of Rights was added to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing, among other things, the right to free speech, it has undergone many test cases. In the mid-1990s, it underwent yet another test when a motion picture, its well-known director, the production company that released it, and a number of other principals were sued by the victim of a “copycat crime” inspired by that particular movie.

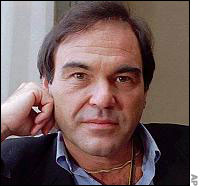

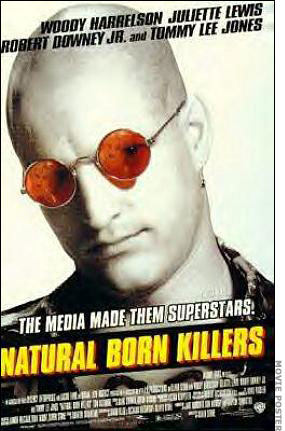

The movie was titled Natural Born Killers and its director was Academy Award-winner Oliver Stone. Its release in 1994 inspired a young couple from Oklahoma to set out on what they planned to be a killing spree that left one person dead and another paralyzed from the neck down.

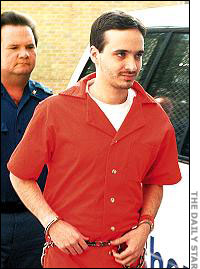

When 18-year-old Benjamin James Darrus and his 18-year-old girlfriend Sarah Edmondson left their rented cabin in Oklahoma on the morning of March 6, 1995, little did they know that their actions would result in a First Amendment test case that went all the way up to the United States Supreme Court. Little did they know, also, that their actions would pit one of Hollywood’s top directors against one of the world’s bestselling authors in a clash of titans. The only thing on the couple’s mind that particular morning was to have fun and mayhem and duplicate the deeds of another couple in a film they watched multiple times.

Seven years after their crimes, through numerous court hearings and appeals, the First Amendment rights of Stone and the other defendants were upheld, but at a heavy price. Despite a preponderance of evidence that young people are influenced to commit violent crimes by what they see in the media, and despite numerous instances of “copycat crimes,” the media was basically absolved of blame for the actions of these perpetrators. A dozen deaths and other violent incidents on two continents were linked directly or indirectly to Natural Born Killers, yet the media and video game companies continue to depict violence in such a way as to almost glorify it.

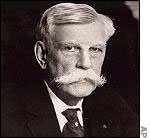

On the one hand in the case was the right of a film’s writers and director to free expression of their creative efforts. On the other hand was the contention of the plaintiffs and their attorneys that freedom has its limitations. In the 1919 case Schenk v. United States, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., the great Supreme Court Justice, delivered a landmark opinion that, while free speech is indeed protected by the Constitution, no one has the right to yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater — or incite others to commit acts of violence.

How this case made its way into the international headlines is a story that began in a small Oklahoma town for two people on hallucinogenic drugs with an obsession for R-rated movies, and it ended in tragedy for two innocent people.

Muskogee, Oklahoma, is a small city of just under 40,000 people in the eastern quadrant of the Sooner State. It is perhaps best known for Merle Haggard’s late-1960s song, “Okie From Muskogee,” that became a pro-American, anti-hippie anthem during a turbulent era in our nation’s history. Depicted as a bastion of patriotism where real men wear leather boots and “We still wave Old Glory down at the courthouse,” Muskogee was home to Sarah Edmondson. She was born on July 26, 1976, just three weeks after the nation’s Bicentennial.

But, despite Haggard’s boast that “we don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee; We don’t take our trips on LSD,” by the ’90s, young people in eastern Oklahoma were doing just that. Including Ben Darrus and Sarah Edmondson. The drug culture that began in the large American cities and college towns in the 1960s had filtered down to small town America within the span of a generation.

Their lives couldn’t have been more opposite. Sarah was an honors student in high school, born into a wealthy and influential family in Oklahoma politics. Her father, James E. “Jim” Edmondson, was a longtime district court judge for Muskogee County, elected in 1983. Her grandfather, Ed Edmondson, was a U.S. Congressman who ran twice for the U.S. Senate as a Democrat. Her great-uncle, James Howard Edmondson, was governor of Oklahoma from 1959-1963, when he was appointed to fill a vacancy in the U.S. Senate caused by the death of his predecessor. In keeping with the family tradition of public service, Sarah’s uncle, Drew Edmondson, has been Oklahoma’s Attorney General since 1994.

Sarah had everything in the world going in her favor; looks, intelligence, personality, popularity, and no shortage of political connections. Had she chosen to go into the practice of law and keep alive the Edmondson family tradition of public service, she would no doubt have received plenty of encouragement and financial support from her prominent, well-connected family.

Ben Darrus’ background was very different from Sarah’s. Hailing from Tahlequah, Oklahoma, not far from Muskogee, his father was an alcoholic. He divorced Ben’s mother twice, then later committed suicide. Ben dropped out of high school and had a history of drug abuse and psychiatric treatment.

Sarah graduated with honors in May 1994 and spoke to her parents about possibly pursuing a career in journalism. However, after three weeks in a junior college, she dropped out and took a job as a waitress to repay her parents for tuition. In January 1995, she tried college again, enrolling at Northeastern Oklahoma State University in Tahlequah, but she dropped out the following month. In all likelihood, it was while attending college there that she met Ben.

If Ben had a negative influence on Sarah, it was only because the potential was already there. Since her early teens Sarah had a history of drug abuse and psychiatric problems. She underwent “severe emotional stress” following the death of her grandfather, Ed Edmondson, in December 1990. Soon after that her best friend committed suicide and several other friends were killed in an auto accident. She was committed to a psychiatric hospital at the age of 13 and, after an eight-week stay, she continued therapy as an outpatient.

The early warning signs were there when Sarah’s parents met Ben for the first time. According to Sarah’s mother, Suzanne Edmondson, when they first met Ben he was very quiet and appeared troubled. “He just sat there staring at Sarah. I tried to get him to talk to us but he just answered questions with ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ so I quit talking to him,” Suzanne recalled.

A month after enrolling at Northeastern Oklahoma, Sarah dropped out. Her parents did not hear from her again for about a month. By that time the damage had been done.

On the evening of March 5, 1995, about a month after Sarah dropped out of college for the second time, she and Ben secluded themselves in a cabin belonging to Sarah’s parents. There they repeatedly dropped LSD and proceeded to watch a videotape of Oliver Stone’s movie, Natural Born Killers, numerous times.

In the movie, two lovers, Mickey and Mallory (played by Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis), go on a multi-state killing spree in the Southwest, taking 52 lives in a three week period. In so doing, they take on celebrity status, thanks to the publicity given to them by a TV crime show host, Wayne Gale (Robert Downey, Jr). The couple is finally caught and imprisoned, but an interview Mickey gives to Gale on Super Bowl Sunday incites a prison riot. During the riot, Mickey and Mallory escape, killing another fifty or so people in the process, including Gale, the prison warden, and the detective who was responsible for their capture. At the movie’s end, Mickey and Mallory have children and are seen happily rambling along the highway in their Winnebago.

In the century-old history of filmmaking, countless movies (and later TV and cable shows and video games) have been blamed for inspiring acts of violence. One of Hollywood’s first great epics, D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, was accused of fostering a resurrection of the Ku Klux Klan and an increase in lynchings after its release in 1915. In the late 1960s, A Clockwork Orange inspired a number of forced home entries and rapes. But no film in history was linked to more acts of violence than Natural Born Killers. And the ability of the film’s protagonists to get away with their crimes made the imitation of them all the more appealing to “copycats.”

Ben Darrus was one of them. In his tripped-out state, apparently, Ben began having fantasies of duplicating Mickey and Mallory’s feats, with Sarah as his partner in crime. In her later confession, Sarah said Ben talked gleefully about invading a random farmhouse, slaughtering all of its occupants after robbing them, then moving on to the next victims. This is what Mickey and Mallory did in the movie.

On the morning of March 6, 1995, Sarah and Ben packed her Nissan Maxima with canned goods and blankets and headed toward Memphis, Tennessee where they heard that the Grateful Dead were having a concert. They also packed along a loaded .38 special that was in the cabin and belonged to Sarah’s father. (Sarah later claimed she brought it along to protect herself from Ben, if the need arose.) Heading south, they hooked up with I-40 and drove all the way across Arkansas, arriving in Memphis only to find out that the Dead concert was still a few days away. With time on their hands, the couple mulled over what to do next.

Hernando, Mississippi is the seat of government for DeSoto County which lies immediately to the south of Memphis. It is a quiet town of less than 7,000 people with a traditional downtown surrounding the courthouse square. To the west are the popular gambling casinos of Tunica County.

Hernando was the next stop for Sarah and Ben. It was apparently chosen at random, lying just off I-55, as the couple headed south toward New Orleans. According to Sarah’s later confession, Ben test-fired the gun in a remote locale after they exited the interstate and was satisfied that it worked. Their next task was to find a victim.

Again, according to Sarah’s confession, Ben talked about finding an isolated farmhouse and killing people while she claimed to be opposed to this. She reportedly accused him of fantasizing about the movie but she did nothing to dissuade him from what was apparently his mission. He professed a hatred for farmers and told Sarah this was the place where he would kill.

But it wasn’t a remote farmhouse from which the victim would come. It was a cotton mill about two miles south of Hernando that was managed by William “Bill” Savage. A 30-year employee of the plant, Savage had an influential friend, bestselling author John Grisham, who was once an attorney in DeSoto County and was elected to the Mississippi State Legislature. Grisham described Savage as “active in local affairs, a devout Christian, and solid citizen who believed in public service and was always ready to volunteer.”

It was around 5:00 on the afternoon of Tuesday, March 7. Bill Savage was alone in his office next to the cotton mill. Sarah and Ben pulled up in the parking lot near the office and entered. Ben had told Sarah to “act angelic” so that whoever was there wouldn’t be suspicious of them. Ben asked Savage for directions to I-55 and, according to Sarah, Savage appeared to know they were up to something. As he gave the directions, he came around his desk toward Ben, and Ben whipped out the .38 and shot Savage in the head.

“He (Savage) threw up his hands and made a horrible sound,” Sarah later stated in a confession, and for a brief moment, he and Ben grappled. Ben shot him a second time and Ben rummaged through Savage’s pockets and took his wallet.

As Savage lay on the floor dying, the couple took off. Ben went through Savage’s wallet and removed two one-hundred dollar bills and the credit cards. He threw Savage’s driver’s license out the window and, according to Sarah, he appeared to be pleased with himself and what he had done. “Ben mocked the noise the man made when Ben shot him. Ben was laughing about what happened and said the feeling of killing was powerful.”

Savage’s body was found by an insurance salesman making a routine call. His murder stumped local investigators and stunned the community. He had no enemies that anyone knew about and, indeed, was well-loved by all who knew him. The only motive the investigators could deduce was that he was the victim of an armed robbery. Probably gamblers trying to obtain money to play the casinos in Tunica. Other than the bullets found in the body, there were no other clues left at the crime scene.

With two hundred dollars of Bill Savage’s money in their pockets, Ben and Sarah continued south on I-55 toward New Orleans, nearly 400 miles away. They partied in the French Quarter and apparently spent all or most of their money there. Heading north on I-55 on Wednesday, March 8, they knew they would need to replenish their funds at someone else’s expense.

Heading north from its junction with I-10, about thirty miles west of New Orleans, the first twenty or so miles of I-55 are elevated above a vast watery expanse known as the Manchac Swamp. There are no sizable towns along this stretch. The first town one hits as soon as I-55 descends to solid, dry land is Pontchatoula. Ben and Sarah decided to strike there next.

Ponchatoula, Louisiana is a quaint community of early 20th-century brick buildings and a main street lined with antique and curio shops. A restored Illinois Central Railroad depot houses more antique and curio kiosks, and outside, on a siding, sit several old, restored railroad cars. In a nearby pool, an alligator with his jaw taped shut advertises a local alligator farm. The hub of a fertile agricultural region, Pontchatoula hosts an annual Strawberry Festival every April that draws well over 100,000 people to this town of only 5,000 residents.

Thirty-five year old Patsy Ann Byers was working the late shift at Time Saver, a convenience store in Pontchatoula, just off I-55. Sometime around midnight on March 8, when no one else was in the store, Sarah Edmondson entered and approached the checkout counter with a candy bar. As Byers prepared to ring up the purchase, Sarah leveled the .38 at her and shot her, point-blank, in the throat.

The bullet severed Byers’s spinal cord, and she collapsed to the floor, bleeding. Sarah screamed and fled but, as she got back to the car, Ben asked her if she got any money. Forgetting the reason she had gone into the store, she returned and saw Byers lying on the floor below the cash register. She said, “Oh, you’re not dead yet,” and Byers pleaded, “Don’t kill me.”

Fumbling with the cash register, Sarah was unable to open it, and Byers, fearful for her life, explained how to get it open. Sarah fled with $105 from the register, leaving Byers lying on the floor to die.

Byers, however, did not die immediately. She was paralyzed from the neck down, unable to move any of her limbs. The wife of Lonnie Byers and mother of three children ranging from ages 4 to 18, Patsy was rushed to a local hospital, then later transferred to a rehabilitation clinic in Houston where she was kept alive on a breathing apparatus. More than two years later, she died of cancer.

The robbery and shooting were captured on the store’s video surveillance camera. Full frontal shots of Sarah could be clearly seen and they were broadcast all over the news on New Orleans television channels. However, the police had no clues as to Sarah’s identity and, for the next three months, the shooting remained an unsolved mystery.

At the time of the Savage murder and the shooting of Byers, authorities in Louisiana and Mississippi had no evidence or motive to connect the two incidents. Both continued to baffle investigators, long after Sarah and Ben returned to Oklahoma. However, as the saying goes, “Loose lips sink ships,” and the two of them were unable to keep silent about their deeds. They began bragging about what they did and an anonymous informant reported what they heard about the Byers shooting to Louisiana authorities.

Sarah was arrested at her parents’ home on June 2, 1995. Soon the full story emerged. Sarah confessed and implicated Ben in the murder of Bill Savage. She was granted immunity by the State of Mississippi in exchange for her testimony against Ben. The two then began sniping at each other, each one accusing the other of instigating the violent spree. In Louisiana was charged with attempted second degree murder, armed robbery, and illegal use of a firearm in the commission of a violent crime.

Ben was also charged with armed robbery in the shooting of Byers and was being held, along with Sarah, in the Tangipahoa Parish Jail in the parish seat of Amite. Her bond was set at $1 million. Ben would later be charged with first-degree murder in the death of Bill Savage and he also later pled guilty to the armed robbery charge in Tangipahoa.

As reported in the July 30, 1995, edition of the (New Orleans) Times-Picayune, the Edmondsons said they were standing by their daughter, despite the charges against her. “She’s the light of my life,” Jim Edmondson was quoted as saying. “She’s daddy’s girl.”

The Edmondsons came to visit Sarah in the parish jail on July 26, Sarah’s nineteenth birthday. On that same day, in Tangipahoa Parish Court, attorneys for Byers and her family filed a civil lawsuit against Sarah and Ben for an unspecified amount of damages stemming from the shooting incident that left Byers paralyzed. The damages included physical pain, disability, medical expenses.

One of the Byers family attorneys, Joe Simpson of Amite, acknowledged that Sarah and Ben “may not have substantial assets, but their story may be worth a lot. There may be a book or movie rights” involved in their story, Simpson said, adding that if the couple did sign a book and/or movie deal, he would try to attach the profits to help pay the Byers family’s expenses.

In the first month after the story became public, Jim Edmondson told the Hammond (La.) Daily Star that he received 130 letters from people about Sarah. All but one of them were supportive. The one that wasn’t supportive was from a woman in Lafayette, La., who said Sarah should be shot in the neck and paralyzed so that her parents would be forced to care for her, and they would know what Patsy Byers and her family were going through. In response, Jim said that would be preferable to having his daughter in a jail cell.

The Edmondsons also expressed a desire to meet Patsy Byers and her family and “begin the healing process,” according to Suzanne. “Our church prays for her, as well as Sarah,” she added.

In March 1996, Byers and her attorneys dropped a bombshell. They filed a lawsuit in 21st Judicial District Court in Tangipahoa Parish against Natural Born Killers director and co-writer Oliver Stone. Also named were thirteen other defendants, including the movie’s production company — Warner Brothers — and other Time Warner subsidiaries, as well as independent production companies responsible for producing and distributing the film. Also named as defendants were Sarah, Ben, Suzanne and Jim and their insurance carrier, as well as the movie’s underwriters.

Exempted from the lawsuit was one of the screenplay’s co-authors: Quentin Tarantino. According to reports, Tarantino was so disenchanted with the cuts and changes made to the final draft that he disavowed any role in the movie’s creation. He asked that his name be removed from the credits but it wasn’t done.

The Byers family attorneys now included Ron Macaluso of Hammond and Rick Caballero of Baton Rouge. The Edmondsons and their insurers were named in the suit because they left a loaded gun in the cabin where Ben and Sarah shacked up while dropping acid and watching Natural Born Killers. But it was obvious that the real targets were Stone, Warner Brothers, and others involved in the making and distributing of the movie.

The lawsuit, again for an unspecified monetary amount, sought to recover “past, present, and future” income, medical expenses, loss of enjoyment of life, mental and physical pain and suffering, and future disability and scarring.”

Immediately, the media and the Hollywood film community rallied to Stone’s defense. Claiming the freedom of speech protections offered under the First Amendment, they maintained that, should the lawsuit be successful, it would stifle artistic creativity and result in excessive censorship. Stone and his co-defendants found powerful allies in all four television networks, the Recording Industry of America, the Motion Picture Association of America, and other media industry heavyweights. The Writers Guild of America and the American Library Association also joined in support of Stone and the others.

Meanwhile, in January of 1996, Sarah was reporting to Mississippi authorities that when she shot Byers she saw “a demon. A woman was working (there). As I looked at her I did not see her. I saw the demon, I shot it, she fell and I ran out of the store and got in (the car). I was crying and screaming, ‘I just killed him!'” Not surprisingly, one of the undercurrents of Natural Born Killers was that Mickey and Mallory were also supposedly tormented by demons when they went on their murderous rampage.

Of course, the authorities were not buying her explanation of the shooting, but her confession was their key to indicting Ben in Savage’s murder.

Sarah also told the authorities that Ben threatened to kill her if she did not take “her turn,” according to a report in the January 26 issue of the Times-Picayune. Apparently he meant that, since he had done the first killing, she had to kill someone also. Ben kept reminding her, “We’re partners,” she reported, and he felt no remorse about killing Savage.

Sarah also claimed that she was turned off by Ben’s repeated demands that she kill someone. She said she considered killing herself instead, but didn’t, and went along with his demand when she shot Patsy Byers.

In the meantime, the defendants tried unsuccessfully to obtain a change for venue, owing to the widespread publicity the case was getting in Louisiana.

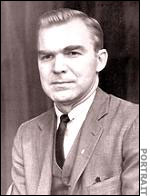

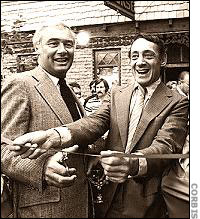

What Oliver Stone is to the film industry, John Grisham is to the literary world. A lawyer and Mississippi State Legislator from 1983 to 1990, Grisham has appeared on the New York Times bestseller list for more than a decade and a half. Every book he writes is virtually guaranteed bestseller status, and many of his books have been adapted into movies. His books have sold millions of copies, making Grisham one of the wealthiest authors of all time.

As an attorney and prominent literary figure, Grisham was an unlikely candidate to call for a First Amendment exception to be made in Stone’s case. Attorneys and authors usually are among the first people to defend freedom of speech but, in this instance, Grisham could not be an objective outside observer. He had a specific interest in the case, namely his loyalty to and friendship with one of the victims: Bill Savage.

As previously mentioned, Grisham knew Savage from his years practicing law in DeSoto County. In an article published in the April 1996 issue of the Oxford (Miss.) American, Grisham described Savage as “soft-spoken, exceedingly polite, always ready with a smile and a warm greeting.” When Grisham ran for the state legislature, Savage was one of his strongest and most loyal and encouraging supporters. On the night of his election victory in 1983, according to Grisham, Savage came up to him and told him, “The people have trusted you. Don’t let them down.”

After laying out the full sequence of events in his lengthy article, Grisham elaborates on his rationale for supporting the lawsuit against Stone and company. In a series of scathing paragraphs, he attacks Stone and his reasons for making the film. Grisham contended that, although Sarah and Ben were troubled youths, they “had no history of violence. Their crime spree was totally out of character” for them. As for the film, itself, Grisham called it “a horrific movie that glamorized casual mayhem and bloodlust. A movie made with the intent of glorifying random murder.”

One of Stone’s defenses of the movie was that it was supposed to be a satire on the media’s and the public’s glamorization of violence. However, Grisham laced into this explanation. “A satire is supposed to make fun of whatever it is attacking. But there is no humor in ‘Natural Born Killers,'” he wrote. “It is a relentlessly bloody story designed to shock us and to further numb us to the senselessness of reckless murder. The film wasn’t made with the intent of stimulating morally depraved young people to commit similar crimes, but such a result can hardly be a surprise. Oliver Stone is saying that murder is cool and fun; murder is a high, a rush; murder is a drug to be used at will. The more you kill, the cooler you are. You can be famous and become a media darling with your face on magazine covers. You can get by with it. You will not be punished.”

To get back at the film industry for turning out gory movies of this type, Grisham suggested two courses of action. One was a boycott of the film, but he conceded that it probably wouldn’t work. Curiosity about why the film was being boycotted would likely stimulate enough interest to generate a strong box office. The second course of action he suggested was a lawsuit.

In pursuing the latter course, Grisham took a legalistic approach in trying to define a movie as “a product,” and therefore subject to product liability laws. He likened movies to breast implants or defective motor vehicles. If they go bad the victim has recourse to sue the manufacturer or provider of the service. The same analogy, he said, should apply to moviemakers.

“The notion of holding filmmakers and studios legally responsible for their products has always been met with guffaws from the industry. But the laughing will soon stop,” Grisham continued. “It will take only one large verdict against the likes of Oliver Stone, and his production company, and perhaps the screenwriter, and the studio itself, and then the party will be over … A jury will finally say enough is enough; that the demons placed in Sarah Edmondson’s mind were not solely of her making.

“Once a precedent is set, the litigation will become contagious, and the money will become enormous. Hollywood will suddenly discover a desire to rein itself in.

“The landscape of American jurisprudence is littered with the remains of large, powerful corporations which once thought themselves bulletproof and immune from responsibility for their actions. Sadly, Hollywood will have to be forced to shed some of its own blood before it learns to police itself.

“Even sadder, the families of Bill Savage and Patsy Byers can only mourn and try to pick up the pieces, and wonder why such a wretched film was allowed to be made,” Grisham concluded.

Though not a bestselling author, Oliver Stone’s stature in the motion picture industry puts him on a par with Grisham. A two-time Academy Award winner for Best Director (for Platoon, 1986, and Born on the Fourth of July, 1989), Stone has been one of the most successful and controversial film directors of the modern era. Most of his movies have become box-office smashes, even while Stone, himself, has become a lightning rod for criticism from all points on the political compass.

His 1991 film, JFK, winner of two Academy Awards, was blasted by some critics for lending credence to previously discredited conspiracy theories behind President Kennedy’s assassination. Many felt his 1996 biopic, The People v. Larry Flynt, which Stone produced, overly glorified the man who proudly calls himself “Mr. Pornographer.”

A decorated veteran of the Vietnam War, Stone was never one to back away from a fight, regardless of its source. Intelligent and articulate in defense of the works he has brought to the screen, he is rabid and uncompromising when it comes to issues involving the First Amendment. Indeed, that theme was the basic underpinning of The People v. Larry Flynt. Though claiming to be genuinely remorseful over the consequences that resulted from the viewing of Natural Born Killers, Stone is quick to place blame squarely on the shoulders of the real-life perpetrators, not on the film itself.

“To my mind, almost everything that was important about ‘Natural Born Killers’ was overlooked amid all that hysteria over the death toll, and all the nonsense about whether or not I was promoting violence or instigating murder,” Stone said. “Once you start judging movies as a product, you are truly living in hell. What are the implications for freedom of speech? You wouldn’t have any film of stature being made ever again.”

He compared the lawsuit with the infamous case of Dan White, the ex-cop who shot San Francisco City Councilman Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone in 1978. “White used what was known as the ‘Twinkie defense.’ He said that he had been eating too many (Hostess) Twinkies and that the high sugar content had prompted him to kill. And it worked! He got away with a lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter and served five years. But you can’t blame the Twinkies in the same way that you can’t scapegoat the movies. You can’t blame the igniter. People can be ignited by anything. And yet this is something we’re seeing more and more of in America today. It’s a culture of liability lawsuits. The whole concept of individual responsibility has been broken up and passed around.”

Milk

When asked if a film can influence its viewer, Stone replied, “Of course it can. But it’s not a film’s responsibility to tell you what the law is. And if you kill somebody, you’ve broken the law … And yes, people may have been influenced by the film in some way, but they had deeper problems to contend with.”

“Natural Born Killers was never intended as a criticism of violence,” Stone explained. “How can you criticize violence? Violence is in us — it’s a natural state of man. What I was doing was pointing the finger at the system that feeds off that violence, and at the media that package it for mass consumption.

“The film came out of a time when that seemed to have reached an unprecedented level. It seemed to me that America was getting crazier.”

While the heavyweights slugged it out over First Amendment rights and whether or not movies should be judged as a “product,” Sarah and Ben preparing to accept their respective fates. Neither one of them would ever go to trial, but a long road had to be traveled before that conclusion would be reached. Their confessions and plea bargaining agreements allowed investigators to wrap up the case, but the scenario grew complicated as byzantine legal issues played against each other at all levels of the Louisiana judiciary system.

A former State District Judge, Edward Brent Dufreche, had ruled that prosecutors could use Sarah’s confession statement in the Louisiana case, even though it was made under an immunity agreement with Mississippi. He also refused to provide court money to pay experts in her defense. One of Sarah’s defense attorneys, James Boren, appealed both rulings. Boren told the appeals court that immunity in one state is binding in another, so Sarah’s statement in Mississippi could not be used against her in a Louisiana trial.

In June 1997, more than two years after Sarah and Ben’s crime spree, the First Circuit Court of Appeal for Eastern Louisiana heard Sarah’s appeal. On the other side of the case, Assistant District Attorney Don Wall contended that if her statement was disallowed, prosecutors would be faced with the burden of trying to prove a case from sources independent of Sarah’s statement. He argued that her confession offered the best path toward resolution of the Louisiana case.

The circuit court initially ruled against Sarah, then reconsidered and reversed itself in her favor, after prompting by the Louisiana Supreme Court. This prompted the prosecutors to take their case directly to the Louisiana Supreme Court for a ruling.

In November 1997, Patsy Byers died at the age of 38 from complications resulting from cancer. Her death came a day before she was slated to give videotaped testimony against Sarah. Her family, however, continued their lawsuit against all the defendants, including Sarah, Ben, Stone, Time Warner, and all the rest of those named in the court records. Lonnie Byers, at the time, said, “The kids (Sarah and Ben) got their justice, and if Oliver Stone was a part of this, he needs to pay his dues, too. I think Stone was just as wrong as the kids who shot my wife.”

The Louisiana Supreme Court agreed to hear the case in February 1998. One justice said she was unable to find any precedent governing immunity in confessions involving two jurisdictions, but Boren cited the precedent of General Oliver North during the Iran-Contra hearings of the late 1980s. Scott Perrilloux, District Attorney for the 21st Judicial District of Louisiana, argued that Sarah’s confession was voluntary and therefore not protected in Louisiana. He also contended that her confession of the Louisiana incident went beyond her obligation to give information to Mississippi authorities.

In July 1998, the state’s highest court ruled 5-2 that Sarah’s Mississippi confession could be used against her in Louisiana. Sarah, the court noted, could have had a provision inserted into her statement that any information she gave to Mississippi authorities would be done in confidence and not used against her elsewhere. Her failure to do this, and her inability to realize that statements made in one locale could be of use to other authorities attempting to solve crimes, was her own fault, the high court said in its ruling. Chief Justice Pascal Calogero and one other justice, ruling for the minority, tried unsuccessfully to claim that Sarah was protected under the Fifth Amendment’s provision against self-incrimination.

Left with no recourse, Sarah pleaded guilty to all the charges against her in October 1998. Sentencing was set for the following month. Sarah could have been sentenced to up to 120 years in prison; instead it was lowered to 35. Boren contended that the State Supreme Court ruling didn’t influence Sarah’s change of plea, and that she had wanted to plead guilty from the start, but he strongly advised her not to. Sarah’s guilty plea, Boren said, was a means of attaining “closure,” both for herself and her family and for the Byers family. Present in the courtroom that day were members of Sarah’s family, minus Jim who was presiding over a criminal trial in Muskogee, and members of the Savage family.

In December 1998, Ben was also sentenced to 35 years in prison for his part in the Byers shooting and armed robbery. He was later extradited to Mississippi where, based on his guilty plea, he was sentenced to life imprisonment at the state prison in Parchman, Mississippi. Sarah was remanded to the Louisiana Women’s Correctional Facility in St. Gabriel, Louisiana.

While the drama over the fate of Sarah and Ben was fading into the shadows, the larger fight over the First Amendment continued to rage. Following the March 1996 filing of the lawsuit against Stone and the others, the case took more than six years to finally settle, after numerous hearings and appeals. However, the media attention given to the case continued unabated.

In an op-ed piece in the Times-Picayune on Sunday, July 7, 1996, acerbic columnist James Gill wrote that Woody Harrelson had been rejected by Grisham for a role in A Time to Kill, based on a Grisham novel, because of the role Harrelson played in Natural Born Killers. Gill, however, was quick to point out that the movie made from Grisham’s book might inspire some enraged parent somewhere to “go out and blow away some rapist, regardless of who is cast in it (the role). If Grisham ever does get sued he may change his mind about equating literature with breast implants.”

Calling Sarah and Ben “a couple of dopeheads,” Gill said, “Natural Born Killers didn’t make them depraved and they would have come to no good, regardless. But it is arguable that repeated viewings could push a susceptible nut over the edge. It would certainly behoove Stone to display a little concern over the effects of his work or even to exercise some voluntary restraint. But we can’t abridge the First Amendment rights of artists just because they are jerks.”

Clancy DuBos, a New Orleans attorney, respected political observer, and co-owner of Gambit Weekly, noted in a column on June 1, 1998, that “recent cases show that courts may be coming around to the Byers’ point of view with regard to ‘artistic’ expressions.” However, he went on to conclude, “Indeed, it’s hard to argue that it’s time to put violence on trial. The question is, in condemning the message, do we also condemn the messenger?”

Other media observers were equally brutal in their assessment of the consequences, should the final judgment go against Stone and his co-defendants. Bill Walsh, a media specialist from Billerica, Massachusetts, while calling Natural Born Killers “too gory and violent,” nonetheless raised some pertinent related questions. “Can you sue Columbia Pictures if a kid clunks his brother over the head with a hammer after watching The Three Stooges? Can you sue Riverside Press if you kill someone after reading Shakespeare’s Macbeth?”

In a lengthy feature in the May 5, 1999, Village Voice entitled “The Movies Made Me Do It,” Michael Atkinson laid out a lengthy list of movies that inspired violent acts dating back to Birth of a Nation. He even cited the cable TV animated show, Beavis and Butt-head, as being blamed for a number of violent incidents committed against children and adolescents by other children and adolescents.

However, Atkinson acknowledged that Natural Born Killers did indeed factor into a number of murders and other violent crimes committed by individuals who watched the movie. He wrote, “Movies are movies, homicidal nuts are homicidal nuts, and the crimes would occur with or without a movie’s sensationalized prodding. So the wisdom goes. But … could it be that visual media aren’t merely a harmless, ephemeral diversion from reality, but a powerful factor in that reality bearing consequences we haven’t foreseen?”

But, in the end, the question over culpability would be settled in and by the courts. Columnists and panelists could pontificate as much as they wanted from either side of the political spectrum, their views likely had little to do with the case’s final outcome.

On January 23, 1997, the 21st Judicial District Court ruled in favor of Stone and the other defendants. The court found that “the law simply does not recognize a cause of action such as that in Byers’ petition.” An immediate appeal was filed by Byers and her attorneys.

The suit continued despite Byers’s death later that year and, on May 15, 1998, the Louisiana First Circuit Court of Appeal tossed out the lower court’s ruling. They ruled that Natural Born Killers fell within the “incitement” exception to the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech; that is, it advocated “the use of imminent force or unlawful action.” The appeals judges determined that Stone’s intent was to incite people to commit violent crimes, and was therefore not eligible for First Amendment protection. The case was allowed to proceed to trial.

Stone’s attorneys petitioned the Louisiana Supreme Court to hear the case, claiming that, “No court in America has ever held a filmmaker or film distributor liable for injuries allegedly resulting from the imitation of a film.” Their argument went on to say, “The specter of such boundless liability would cause those who create movies, music, books, and other creative works to avoid controversial or provocative subjects.”

However, the State Supreme Court was unswayed by their arguments. In October of that year the seven justices voted unanimously to decline review the Court of Appeals’ decision, thus allowing it to stand. Stone and his attorneys then took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court where, on March 8, 1999, the High Court also declined to intervene. This also meant that the circuit court’s decision would stand. This was considered a victory by the Byers family but the issue would be far from settled.

Four months later, Stone agreed to give a deposition on his side in the case, including his motives for making the movie. His attorneys said he would come to Louisiana to file the deposition by the end of the year. Plaintiff attorney Joe Simpson said, among other things, he wanted to see materials related to how Stone and Time Warner were promoting the movie. “We have to show that he intended to provoke violence,” Simpson told reporters.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs cited a recent precedent handed down by the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1997. In the case of Rice v. Paladin, the court ruled that a book publishing company, in this case Paladin, could be held liable for the actions of readers of a book that was essentially a manual for contract killers. The book, Hit Man: A Technical Manual for Independent Contractors, was linked to a murder-for-hire, despite the publisher’s contention that the book also provided a valuable educational service for law enforcement personnel and writers of mysteries and true crime books.

However, Rodney Smolla, a law professor representing the Rice family in the Hit Man case, cautioned the Byers family attorneys that the two cases were very different. He said movies like Natural Born Killers are intended “to entertain people and a murder manual is meant to train people.”

On March 12, 2001, the tawdry courtroom saga over Natural Born Killers came to a climax where it began four years earlier: in a summary judgment from the bench by 21st Judicial District Judge Robert Morrison. He ruled that Stone and his co-defendants could not be held liable for the actions of those who saw the movie. Nor was the movie considered to be “obscene” since violence doesn’t fall under the definition of obscenity, and is therefore protected by the First Amendment.

In the judge’s ruling, he said that the plaintiffs didn’t have enough evidence to hold Stone and the others accountable for the violence that may have resulted from the film’s viewing. Morrison said several days had elapsed between the viewing of the film by Sarah and Ben and the two shootings which, he felt, would have given them sufficient time to reconsider their actions.

By this time there were more than a dozen “copycat killings” being blamed on the film. Similar lawsuits had been filed in other states but they, too, were thrown out of court.

“This is an important victory for the First Amendment,” said Walter Dellinger, an attorney representing Time Warner and Stone. “Artists simply could not do their work if they had to second-guess themselves,” and fear that their work could lead to lawsuits and monetary damages.

Byers family attorneys contended that publicity materials for the movie targeted young males around Darrus’ age, and they promised to appeal. Rick Caballero expressed a hope that the case could go to the U.S. Supreme Court where a ruling might be made that violence is, indeed, a form of obscenity exempted from First Amendment protection. “We are trying to make video game producers and movie producers act in a more responsible way,” Caballero said. “The only way they will listen is to threaten their wallets.”

However, despite its noble intentions, the Byers family lawsuit met its final defeat in June 2002 when the Court of Appeal upheld the lower court ruling. Seven years and countless hours spent on legal maneuvers merely left the matter where it had always been: in the hands of the filmmakers and other purveyors of artistic products. The First Amendment had survived yet another challenge but, at what price?

The surviving members of the families of William Savage and Patsy Byers know what that price is. They have paid it.

In July 2007, a girl who participated in a triple homicide was convicted in Canada. Due to her age, Canadian media sources observed the Youth Criminal Justice Act and declined to reveal her name, but it has turned up in many international reports.

On April 23, 2006, in a town in southeastern Alberta called Medicine Hat, the parents and younger brother of Jasmine Richardson were discovered murdered in their home. A six-year-old friend came to the house early on Sunday afternoon, saw a body through the window, and alerted his mother, who called the authorities.

Police arrived and discovered three victims. Debra Richardson, 48, lay at the foot of the basement stairs, according to the Ottawa Citizen, covered in blood and stabbed 12 times. Her husband, Marc, was stabbed twice as many times, all over his face and torso, including his crotch. He’d bled out so much there was little left in his body, but from the spatters all over the TV room it was clear he had put up a tremendous fight. Eight-year-old Jacob was found in his bed, with his throat cut.

Detectives sent for the forensic unit to process the scene, and they brought dogs to go through the home and grounds. A white truck sat in the driveway with a smashed window, and another truck belonging to the family was found off the property. Items in the home indicated that there was a twelve-year-old daughter, Jasmine, who was missing. Police did not know if she had been abducted, so a country-wide warrant was issued for her.

Friends of Jasmine’s twenty-three-year-old boyfriend, Jeremy Allen Steinke, pointed authorities to a town in Saskatchewan, and they found Jasmine alive and with Steinke. He was an unemployed high school dropout, considered the unofficial leader of a group of Goth-punks. The two were arrested without incident and returned to Medicine Hat. After a hearing, Jasmine was sent to the Calgary Young Offenders Centre to await a trial. Within days, she had penned an apology letter to her family, admitting she had taken part in their slaughter. She wrote that she wished she could “take it all back” because now she “had no one.” She said her brother was killed because he was too sensitive to survive without her parents. She herself had choked him to make him unconscious.

Supposedly, this all occurred because the seventh-grade girl had reacted badly to being grounded for dating Steinke behind her parents’ backs. They told her she could no longer see him. Yet Jasmine had already agreed to marry Steinke and she was determined to be with him. She urged him to help her get rid of them.

A romantic bond was not all this couple shared: they had a fixation on Goth culture and Steinke even claimed to be a 300-year-old werewolf. Both had posts on a Web site known as VampireFreaks.com, and Steinke reportedly wore a vial of blood around his neck. Jasmine referred to herself on another site as “runawaydevil”. They shared an appreciation for razor blades, serial killers, vampires, and blood. They would soon learn that murder was not fantasy.

During the 2007 trial, covered by reporters from around Canada, some facts about Jasmine came out that indicated her state of mind. Not only did she and her boyfriend ascribe to the darker side of Goth culture, with a fixation on death and imaginary monsters, but they had watched the film Natural Born Killers.

Oliver Stone produced this 1994 film, which is engorged with gratuitous violence. A killing couple, Mickey (Woody Harrelson) and Mallory (Juliette Lewis), were based on spree killers Charles Starkweather and his girlfriend. Throughout the film they commit some 52 murders, including massacres with multiple victims. They start with the slaughter of Mallory’s abusive parents, one by drowning the other by burning, but spare the younger brother. One can see how an angry couple who embrace death culture and find parents an annoying hindrance might see in this film an affirmation of their bid for freedom and a violent solution.

While Jasmine’s apology letter was not read to the jury, deemed to have been gained via improper interrogation protocol, jurors did see a drawing found in Jasmine’s locker that depicted four stick figures. The middle-sized figure throws gasoline on the other three with a smile, lights them ablaze, and then runs to a vehicle labeled “Jeremy’s truck.” In addition, the two had exchanged letters after their arrest that indicated they wished they had run away together. There was no indication in these communications that Jasmine was remorseful or an unwilling accomplice. She also had stolen her mother’s ATM card that night, got money, and had sex with her lover — all pointing to a callous attitude. (Even her apology letter was largely self-pitying.)

Jasmine’s attorney, Tim Foster, accepted the idea that Jasmine might have engaged in discussions about killing her parents, but said she did not mean that she would literally do it. The scenario he painted was that Steinke had gotten high on cocaine, watched the violent movie, and undertook to rescue Jasmine, as “Mickey” had done for “Mallory. ” The idea was his alone, as was the act. Thus, Jasmine, too, was a victim.

She took the stand in her own defense and affirmed that her boyfriend was the killer. She cried when asked about choking and stabbing her brother and said that Steinke had made her do it, as her brother begged for his life. She had a knife in her hand, she said, for self-defense, but Steinke had taken it and slit her brother’s throat.

While the prosecutor conceded that Jasmine did not engage in the act of murder, she had persuaded and encouraged Steinke to do it, telling him which window would be unlocked for entering the home on Saturday night. She also willingly fled with him. Thus, she was eligible for a murder conviction. He urged the jury to remember her part.

On July 9, 2007, after the jury deliberated just over four hours, Jasmine was convicted of three counts of first-degree murder. She began to weep, according to the Edmonton Sun. Under Canadian law, she cannot receive an adult sentence, so she faced a maximum of six years in prison and four of probation. Steinke faces trial for murder next year; he has not yet entered a plea.

Jasmine Richardson is the youngest person to be convicted of multiple murder in Canadian history. For that matter, she’s the youngest in North American history.