C-Murder: Rapper Lives His Lyrics — The Music of the ‘Hood — Crime Library

Once confined almost exclusively to inner-city culture, rap/hip hop is now just as likely to be heard blasting through the open windows of a white teenager’s Mustang in a well-heeled, gated suburban subdivision. Just as raucous black artists like Little Richard, James Brown, Larry Williams, Hank Ballard, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins [DMS1] and others were embraced and welcomed into the culture of a generation of white post-war teens, much to the chagrin of their parents, black rap artists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries are the idols and role models of white, as well as black, youth.

In few places in the United States is this more evident than in New Orleans, Louisiana. Prior to the devastation caused in August and September 2005 by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, the city was 65% African American, with a sizable percentage of them living in public housing projects. Each of the city’s 7,000 public housing units were occupied by an average of three to five people, making for a very overcrowded living environment. And even those who didn’t live in public housing were often jammed into densely populated neighborhoods where a combination of sociological factors, many of which dated back over 200 years, kept them at the bottom of the feeding chain.

It was a culture largely made up of welfare mothers stretching back two or three generations. A culture of absentee fathers, many of whom had children by a multitude of mothers, none of whom they were married to. A culture in which alcoholism and drug addiction was pandemic. A culture of violence, where the sound of bullets being fired was a familiar refrain. A culture with a high dropout rate and low expectations. A culture of despair and desperation.

Not surprisingly, a culture of this type would be reflected in the music emanating from its core. But, unlike the Lou Rawls classic “Dead End Street,” which both captures the harsh realities of ghetto life and expresses an upbeat determination to rise above it, the rap music of the late 20th and early 21st centuries offers little of that hope for its fans. Instead, it largely glorifies the subhuman conditions that prevail and gloats about it. Strutting urban warriors boasting about their female conquests, threatening violence against anyone foolish enough to get in their way. Including the authorities.

Against this backdrop, it isn’t surprising that a number of rap music’s primary artists would find themselves on the opposite side of the law, exemplifying the lifestyles they rap about in staccato monotones. One of them was Corey Miller. Performing under the stage name of C-Murder, he did more than just “see murder” in the eyes of a jury in Jefferson Parish (county), Louisiana. He was convicted of committing one and accused of attempting another. How he got into this situation is the tragic end product of a phenomenal success story that turned sour.

The story of Corey Miller began, like so many other rap artists, in a teeming inner city, in this case New Orleans. He was raised in a run-down, overcrowded cluster of residential buildings officially designated the B.W. Cooper Public Housing Development, but known locally as the “Calliope Project” (pronounced cal-e-ope, not ka-lie-a-pee) in the city’s impoverished Third Ward. Like most of the city’s projects, life in the Calliope “‘hood” was tough and dangerous. Those who had very little material wealth or goods were preyed upon by those who had even less. Drugs were rampant. So were firearms. Murders and violence were commonplace occurrences, especially during turf wars over the lucrative drug trade. Many of those who grew up there pursued lives of crime because few legitimate, good-paying occupations were accessible to them. Dropout rates were high, as were rates of incarceration. Despair was the order of the day.

Against this backdrop, on March 9, 1971, Corey was born, like so many other children to poor black families, in New Orleans’ Charity Hospital. His parents divorced and Corey, along with his brothers and sister, were raised by his grandmother, Maxine Miller, who they affectionately called “Big Mamma.”

Like many of his peers who were also raised in the projects, Corey grew up tough and mean. An older brother, Kevin, had been murdered by a heroin-addicted acquaintance who was trying to rob him. Like many of those who he hung with, young Corey might have ended up dead or serving a long stretch in Angola (the state prison) at an early age, had it not been for the fortuitous circumstances surrounding his older brother Percy Robert Miller, Jr., better known by his stage name of Master P.

Four years older than Corey, Percy was a product of the same culture. But, instead of “going bad,” Percy had lofty goals and ambitions that transcended his dismal surroundings. In less than a decade he transformed a $10,000 inheritance into a $361 million leisure and entertainment empire that employed 100 people. Fortune magazine’s “America’s 40 Richest Under 40” issue (Sept. 1999), listed him as No. 28 of 40 among the nation’s entertainers. He earned $56.5 million in 1998 alone. His major product: rap music.

One of only a handful of project blacks fortunate enough to attend a private, parochial elementary school, Percy Miller went on to graduate New Orleans’ Warren Easton High School and attended Southern University at New Orleans, hoping to win a basketball scholarship to the University of Houston. However, a knee injury kept that from becoming reality. He continued his higher education at a business school, Merritt Junior College in Oakland, California, adjacent to Richmond, California where his mother had moved after leaving New Orleans. Like Chicago’s Lou Rawls in a previous generation, Percy was determined and talented enough to get off the “dead-end street” where he began life and make something of himself.

Upon receiving $10,000 in a wrongful death lawsuit involving his grandfather, Percy, who had aspirations of becoming either a professional basketball player (he was a 6’3″ point guard) or a musician, chose the latter course. He invested his money in a record store in Richmond which he called No Limit. Selling records, at first, Percy was determined to make them as well. He diverted a portion of his profits into some rudimentary recording equipment, a sound system and a basic studio setup. He began writing his own lyrics and recording them, experiencing modest sales in the beginning that steadily grew into ever-larger profits. Taking its name from the store, the record label was also called No Limit, with an army tank as its logo.

When he formed the label in 1993, mainstream rap was dominated by Los Angeles’ Death Row Records, featuring Tupac Shakur, and New York’s Bad Boy Entertainment, featuring Sean “Puff Daddy” (later P. Diddy) Combs. The likelihood of a small Louisiana label operating out of makeshift studios in Baton Rouge supplanting these big city goliaths at that time would have been laughable to anyone who might have dared hint at it. But Percy Miller, by then known as Master P, was never one to let himself be limited by the odds. His choice of the label’s name was deliberate. He was determined to show the world there were “no limits” as to what one could do when they put their mind to it.

Quietly cranking out a blurring succession of recordings of himself and others in his studio’s stable, using Priority Records’ national distribution network, Master P finally showed up in the popular radar in 1997. In September of that year, his “Ghetto D(ope)” album supplanted the far better-known “Puff Daddy” Combs at the top of the Billboard charts. It was the first time in more than 40 years that a New Orleans-born recording artist accomplished this feat, the last having been the immortal Louis Armstrong who overcame similarly impoverished circumstances in his rise to the top of the music world charts.

Within a handful of years after forming his company, Master P had become the dominant player in the hip hop genre. His label was “seemingly able to mint millionaires at will,” according to New Orleans Times-Picayune music writer Keith Spera, as he elevated members of his stable from obscurity to superstardom. No Limit rappers like Mia X (Mia Young, the “Queen of Hip Hop” who Master P discovered working at a New Orleans neighborhood record store while collecting $155 a week on welfare), Fiend (Ricky Jones) and Mystikal (Michael Tyler) were cranking out million-selling albums, as was Master P himself, while rival labels began stagnating.

A major coup was scored when former Death Row mainstay Snoop Dogg (formerly known as Snoop Doggy Dogg) joined the No Limit roster in 1998, leaving Death Row near death. The June 20, 1998 issue of Billboard, the music industry’s bible, listed 11 CDs bearing No Limit’s tank logo in its Top 100 R&B listing of bestselling albums. Soon No Limit artists were starring in MTV music videos and feature films.

By the end of the decade, with a diversified portfolio and business interests expanding into movies (he appeared in a dozen of them), music videos and video games, shoes, clothing lines, talking dolls, paid phone cards, a sports management agency (New Orleans Saints’ top draft choice for 1999, running back Ricky Williams was one of his clients), real estate investments and other ventures, Master P was making bigger bank than Combs’ Bad Boy Records. He owned a house in Beverly Hills, complete with swimming pool and tennis and basketball courts, in the same neighborhood as Will Smith, Whitney Houston and other black entertainment superstars. He owned a second home in an exclusive Baton Rouge subdivision whose residents included former governor Edwin Edwards. His business acumen was noted at that time by a future governor, Kathleen Blanco, then serving as Lieutenant Governor, who called him “an awesome professional.”

As Percy Miller, he even played a little professional basketball for several minor league teams and attended tryouts for the NBA Toronto Raptors and Charlotte (later New Orleans) Hornets. However, he was cut by the Hornets just prior to the start of the 1999 season, thus ending his abbreviated athletic career.

By this time, New Orleans was a major hub of the rap culture, with Cash Money Records and its major stars, Juvenile and The B.G., giving No Limit a run for its money. But No Limit, oblivious to the competition, forged on, minting gold and platinum records and music videos in record number for a “bull market in no-frills reality rap,” in the words of music writer Spera.

Master P’s generosity soon became almost as legendary as his ability to crank out hit records. He donated huge sums of money to numerous worthy causes, especially those designed to uplift ghetto kids and their aspirations. He gave generously to youth sports programs and the playgrounds (parks) on which they perfected their skills, and he donated uniforms to team members. In March 1999, he gave $250,000 to St. Monica School which he attended as a young boy and, more than six years later, following Hurricane Katrina, when the Archdiocese of New Orleans mandated closure of St. Monica Church and School, he donated another $250,000 to help keep them open. Above all else, besides the money he gave, Master P continually expressed his hopes that he could be a good role model and have a positive impact on others “coming out of the projects.”

Like a good brother, Master P opened his heart and his studio to his brothers Vyshonn and Corey, offering them the opportunity to enjoy a little success of their own. They did, selling millions of records under their stage names. Vyshonn became Silkk the Shocker. Corey became C-Murder.

As C-Murder, Corey Miller made his first recorded appearance as a member of Tru, a trio that also featured Master P and Silkk. Their first album, “True,” was released in 1995 and was followed by “Tru 2 da Game” in 1997. During that year, C-Murder appeared on a number of No Limit releases, including Master P’s “Ghetto D” and the “I’m ‘Bout It” soundtrack.

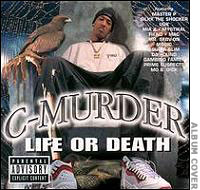

In the spring of 1998, Corey released his solo debut, “Life or Death” and “Bossalinie” followed a year later. In 2000, he reached superstar status, first with his appearance in the 504 Boyz smash hit “Wobble Wobble,” then with his third and most successful album yet, “Trapped in Crime,” propelled by the commercial success of its C-Murder/Snoop Dogg/Magic collaboration, “Down for My N’s.” This album also signaled the launch of Tru Records, C-Murder’s new label, which promised to be accompanied by a clothing line and successive releases. His 2002 release, “Tru Dawgs,” was a test for the label, and it was a success.

Taking his name from the fact that he claimed to have seen many murders, C-Murder was now a hip hop star in his own right. “He’s actually one of the stronger rappers on the label. He may stick to the predictable gangsta musical blueprint, but as a rapper, he had an original style and interesting wordplay that separated him from the No Limit pack,” were the words Stephen Thomas Erlewine and David Jefferies of All Music Guide used to describe him.

Like his counterparts at No Limit and other rap labels, C-Murder’s lyrics spared no one. Everyone and everything was fair game — even members of his own race. In a sample of lyrics (below) from his song “Ghetto Millionaire” (from “Bossalinie”), C-Murder pushes the envelope way beyond what was conventionally acceptable in the pre-rap era.

I cop a Benz at the age of twenty one nigga

I f___ hoes and smoke weed for fun nigga

From the streets to the muthaf__in’ record stores

And sell a million discs at Blockbuster videos

Bitches formin’ lines at my concerts

Them thug niggas sell drugs off my inserts

A eight figure nigga gettin’ bigger

I wear No Limit gear nigga so f___ Tommy Hilfiger

And renegotiate my court case, f___ a plea

And call Cochran there’s a million on legal fees

Charge it to the game, that’s what Silkk said

My name ringin’ like the muthaf__in’ flu spread

Give me a shot cause I’m sick wid it (sick wid it)

The tank on the back, the ghetto niggas gotta get it

I make money so f___ all them haters with the mean stares

I wanna be a ghetto millionaire

In the early years of Rock & Roll, and the years immediately preceding it in the early to mid-1950s, most recordings by black artists contained warning labels. They read, “Not licensed for commercial airplay. For use on home phonographs only.” In many of these cases, the lyrics were more subtle than overt. Metaphorical rather than literal. When the Clovers sang, “Really like your peaches, wanna shake your tree” (“Lovey Dovey,” 1954) they weren’t talking about shaking fruit down from a tree, and anyone listening to the song readily understood that. Even the words “rock and roll” themselves were originally a metaphor for sex, originating from the song “Sixty Minute Man” by Billy Ward and the Dominoes (“I rock ’em and roll ’em all night long, I’m a 60-minute man”).

But, in those days and for many years afterward, song lyric writers policed themselves. The best of them found ways of extolling sex without coming out and saying it in blatant terms. Over time, however, the boundaries and guidelines gradually broke down. By the end of the 20th century, they were gone completely. There wasn’t a cuss word or an ethnic slur that couldn’t be articulated on record. Although the offending words were censored during airplay and the records themselves contain warning labels about explicit lyrics, the records themselves were still played. And they were uncensored when blasted at full volume on home and car CD players. There were no limits on what could or could not be said, and one of the leading proponents of this phenomenon was No Limit Records.

The top-selling single of the year 2000 was recorded by a contingent of No Limit’s stable of artists that included Master P himself, along with brothers Silkk the Shocker and C-Murder. Calling themselves the 504 Boyz after the telephone area code for the New Orleans area, their song was titled “Wobble Wobble.” C-Murder’s “solo” near the end of the record went as follows:

Let me see you wobble then shake it, then baby pop it, don’t break it

You want love let’s make it, I just can’t wait ’til you naked

You lick your lips it makes me hard

daydreamin’ of screamin’ and fiendin’

You creamin’ for sex, that you gonna get this evening

Ya’ heard me.

Previous verses contained even more explicit lyrics, coming right out and saying the “f-word,” the “s-word” and the “n-word,” as well as the “mf-word.” Women are “bitches” and “hoes.” This was no longer their grandfathers’ subtly suggestive rhythm and blues. It was “in your face,” designed-to-shock lyrics — raunchy, raw and uncut. From there, it was only a small step to carrying out the deeds sung about in the lyrics in real life.

However, while Master P capitalized on this trend and parlayed it into a fabulous fortune, he generally stayed on the right side of the law. Over the years he’s had a few minor dust-ups with the authorities, most recently being arrested along with Silkk on concealed weapons charges on the campus of UCLA in early 2006, but he has wisely steered clear of the violence his songs reflect. He is a family man, devoted to his wife of 15 years, Sonia, and his five children, including his 17-year-old rapper son, Lil Romeo. He has also tried to maintain a squeaky-clean image for his label and its artists, even to the extent of canceling the contract of one of his best-selling duos, Kane and Abel (David and Daniel Garcia) after they were busted on drug charges. A year away from turning 40, he seems to have retreated from the spotlight, having attained nearly everything anyone could want out of life.

Not so, though, for younger brother Corey, who rushed in to fill the Miller family vacuum Percy created by his self-imposed retreat into relative anonymity. These days it’s Corey who’s getting most of the ink and the airtime, but not in a good way. A series of major missteps brought the long arm of the law down on him.

On the front cover of his latest CD, “The Truest S__t I Ever Said,” released in 2005, C-Murder is standing defiantly in front of the apartment in the Calliope Project where he grew up. He is bare-chested, wearing a headband, with “C-Murder” tattooed on his abdomen, pointing his finger as if to say, “Yeah, I’m talkin’ to YOU!”, head turned sideways in a tough-guy pose. The term “thug,” which used to be an insult, is now a compliment in contemporary urban America. A badge of honor among those who swagger around, defying authority and exemplifying the “in your face” attitude toward a social system that relegated them to their low economic and social status.

For many, C-Murder has become the poster boy for this thug culture. His newfound wealth and status — along with his fearsome-sounding name — made it that much easier for him to live out his tough-guy lifestyle, oblivious to the consequences. A sheriff of a nearby Louisiana parish accused him of “living out his lyrics.” A volatile, hot-headed young man, he couldn’t separate his stage persona from his street persona. It was bound to get him into trouble and it did. He had a series of minor arrests, including weapons violations, when stopped by the Louisiana State Police while speeding on Interstate 10 between Baton Rouge and New Orleans with a semiautomatic pistol and wearing a bulletproof vest in March 1998. The vehicle was initially believed to have been stolen, but it was later determined that he purchased the vehicle at an auction.

Following the violent deaths of rappers like Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. in the 1990s, rappers were known to wear bulletproof vests, but it was still illegal for civilians to wear body armor in Louisiana for fear of it being used in the commission of violent crimes. Several months later, charges were reduced. Corey was hit with a small, $500 fine and let go. His worst criminal actions were yet to come.

During the ’90s, when rivalries existed between rap record labels, rappers were known to slander each other publicly. This led to the violence that ended the lives of Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. Master P explicitly forbade his artists from doing slandering others, but even he couldn’t control the impulses of his smug, swaggering younger brother. The opposite of Master P in terms of philanthropy, no record exists of C-Murder making charitable donations to anyone or any organization. He came out of the projects and into great wealth, which he flaunted and shared with very few.

Perhaps Corey thought that his fame and money put him above the rules that applied to others, but he found out differently on August 14, 2001 when he and some of his friends attempted to enter Club Raggs in Baton Rouge. When ordered to submit to a search for concealed weapons, he refused. As bouncer Daryl Jackson pressed the issue, Corey asked to speak to the manager, Norman Sparrow, who came out and backed up his bouncer. Corey would have to undergo a search before being allowed to enter.

At this point, a later indictment charged, Corey allegedly pulled a semiautomatic pistol out of his waistband and attempted to fire it at Sparrow. It jammed, and Sparrow’s life was spared. Corey allegedly attempted to fire again, this time at Jackson, and the weapon also failed to discharge. Frustrated, Corey reportedly fired a single shot into the floor and fled in his car, but the incident was captured on a security camera’s videotape. He turned himself in two days after an arrest warrant was issued, charging him with attempted second degree murder. If convicted, he could face up to 50 years in prison. Corey’s attorney, Roy Maughan Jr., said his client is innocent of the allegations.

Released on $100,000 bond — pocket change for a multimillionaire — Corey Miller, alias C-Murder, was free to strike again. And it wasn’t long before he did.

Harvey, Louisiana, is a predominantly blue-collar suburb of New Orleans, lying on the opposite side of the Mississippi River on what is known locally as the West Bank. It is about five miles west of the twin bridges that connect the two sides of the river. Because of its centralized location, Harvey is the commercial hub of the West Bank, with an extensive corridor of strip centers and big box stores along Manhattan Boulevard, and a criss-crossing corridor of seemingly endless car dealerships along the ground-level Westbank Expressway. Near the intersection of these two major thoroughfares is Rainbow Lanes, a now-closed bowling alley formerly called Don Carter Lanes after the great bowler who dedicated the facility nearly two decades earlier.

Adjoining the bowling alley and rising one story above it was the Platinum Club. Today it lies in ruins from a combination of vandalism and the ravages of Hurricane Katrina. Its shattered plate glass is strewn all over, its front doors are boarded up and what’s left of its interior is in total disarray. But in its heyday, in the early 2000s, it was a gaudy, raucous place-to-be; a mecca for young hip hoppers from all over the greater New Orleans area.

Sixteen-year-old Steve Thomas from Avondale, about ten miles west of Harvey, wasn’t even old enough to be in the Platinum Club on the night of January 12, 2002. But he was, anyway. Thomas, a big C-Murder fan who had pictures of his idol all over his walls at home, had heard that his idol was going to be at the club that night. Using a friend’s borrowed ID, Thomas managed to gain entry. What happened several hours afterward would be heatedly debated in a court of law 21 months later.

All that is known for certain is that there was an altercation just off the club’s dance floor around 1:00 a.m., and that an under-aged boy named Steve Thomas was shot to death after having been punched, kicked and stomped by a group of young men. Some witnesses say C-Murder was in the middle of the scuffle, others say they’re not certain, and still others say he was nowhere in the vicinity. No one who has come forward as a witness knows how the fight started or who started it. According to one witness, C-Murder was heard to shout, “You know who the f____ I am?” before a single gunshot was heard.

At least two witnesses among the estimated 300 people in the nightclub told investigators and later testified that they saw C-Murder pointing with his arm toward the victim, as if holding a gun, and they saw a bright flash go off. However, none of them actually claimed to have seen C-Murder fire the fatal shot that took Thomas’ life. What is known, however, is that C-Murder and his entourage didn’t stick around waiting for the police to interrogate them. Immediately after the fracas, they high-tailed it out of there and weren’t heard from for another few days.

At 2:31 a.m. Thomas was pronounced dead on arrival at West Jefferson Medical Center in Marrero, only a mile away.

Steve Thomas’ obituary appeared in the Times-Picayune on Friday, January 18. Earlier that day, in the wee hours of the morning, his accused killer was busted and arraigned.

In the early-morning hours of January 18, New Orleans 8th District Police responded to a call from the House of Blues in the 200 block of Decatur Street. A small group of young black men were reportedly causing a scene outside the popular French Quarter music club, whose part owner is TV and film star Dan Aykroyd. Off-duty NOPD Detective Robert Stoltz, who was working a detail at the club, recognized one of those causing the commotion as C-Murder, whose antics on a prior occasion had earned him a lifetime ban from the premises. According to a police spokesperson, Stoltz knew about some outstanding warrants against the rapper and called the incident in to headquarters.

When the officers swooped in they arrested Corey. He was charged with disturbing the peace and criminal trespass, and shortly afterward they turned him over to Jefferson Parish authorities. He was initially booked on an outstanding attachment, charging him with defrauding an innkeeper. Then he was charged in connection with Thomas’ death. He was formally indicted on charges of second degree murder on February 28.

The case was assigned to Judge Martha Sassone of Division K, 24th Judicial District Court, based in the Jefferson Parish Courthouse in Gretna, La. While prosecutors from the Jefferson Parish District Attorney’s Office and Corey’s lawyers spent the next few months preparing their cases, Corey remained incarcerated in the Jefferson Parish Correctional Center, also in Gretna, adjacent to the courthouse. He was anything but a “model prisoner.” Over the next four years he would be involved in a number of incidents that piled up charges against him.

Sassone initially set bail at $2 million, then revoked it in late April when it was felt that allowing Corey’s release might pose a serious threat to potential witnesses. His ominous-sounding stage name and his fearsome reputation were believed to have been scaring off dozens of people who might have seen the killing but were reluctant to come forward.

Reacting to his younger brother’s arrest, Master P, speaking on MTV, said, “You know what, right now with C, I think he’s a victim of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. When you come from the ghetto, you can’t do those type of things. You can’t hang with the same type of crowd you been running with. We hope that once this is said and done, people will see he wasn’t involved with this. It’s definitely a tragedy for our family. Hopefully this teaches kids that you can’t live that type of life no more.”

But, despite his vast wealth, Master P could not secure the release of his brother, and neither could anyone else. He was considered too much of a risk to the safety of others.

Not long after his incarceration began, it was announced that Corey had allegedly conspired with two Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office deputies, who doubled as prison guards, to smuggle a cell phone and its charger into Corey’s cell. According to Assistant District Attorney Douglas Freese, who was assigned to prosecute the case, the high-profile prisoner wasn’t simply planning to use the cell phone to chit-chat with friends and family: he was allegedly intending to use it to locate and intimidate potential witnesses in the murder case against him. Normally pay phones are available, on a limited basis, to inmates of Jefferson Parish Prison. They can call friends, family and their lawyers, but conversations on the pay phones are routinely monitored by prison authorities (except in cases where attorney-client privileges apply). Not so with cellphones, which operate on outside frequencies.

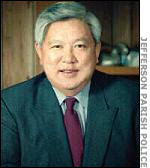

Lee

The two deputies accused of helping Corey acquire the phone were fired by Jefferson Parish Sheriff Harry Lee and the phone and its charger were confiscated. The three of them were later charged with conspiracy to introduce contraband into the jail and bribery. The two deputies were charged with malfeasance in office and later sentenced to two years each in prison.

Corey admitted to being at the Platinum Club on the night of the shooting but denied being involved in the incident. His chief attorney, Ronald Rakosky denied that his client was planning to use the cell phone to intimidate witnesses.

Several months later, adding to Corey’s woes, a prisoner of the correctional facility who claimed to have spoken with Corey and whose name was being withheld by authorities, said the rapper admitted killing Thomas in one of their conversations. The inmate, referred to only as “John Doe,” told a pre-trial hearing before Judge Sassone that Corey also told him that he knew where Freese lived and he knew that the Assistant DA had children. Corey, according to the inmate, said he was “going to reach out and touch him” (Freese). When asked by Rakosky what he thought the statement meant, the inmate replied, “The statement speaks for itself,” implying that Corey was threatening harm against Freese and/or his children.

The unnamed inmate told the hearing that Corey made this statement shortly after he had a visit from Master P in June. He claimed Corey told him that he was at the Platinum Club on the night of January 12 and that, during the argument with Thomas, Corey grabbed a gun from one of his nearby friends and shot Thomas in the chest with it. “I’m not some studio gangster,” the inmate quoted Corey as saying.

Regarding the cellphone, the inmate said Corey told him he wanted to use the phone to tell potential witnesses that it “would either go smooth or it would go full-fledged,” the latter term being understood to mean that a witness could be killed for testifying against him. Under cross examination by Rakosky, the inmate testified that he was being held on forgery and drug charges and, because of his criminal past, he could get a life sentence. He admitted to hoping that, by ratting out Corey, it would weigh in his favor for plea bargaining a lighter sentence. However, he said he received no official promises one way or another.

Also at the pre-trial hearing, Freese showed the judge the videotape of Corey attempting to fire his weapon at the club owner and bouncer in Baton Rouge nearly a year earlier. Sassone ruled that the tape was proper to admit into evidence at the jury trial. Rakosky argued, unsuccessfully, that since no shots were fired in the Baton Rouge incident, the tape was irrelevant and would be prejudicial to his client.

After the hearing, Freese said steps were being taken to ensure his safety and that of his family. Corey was then forbidden to have visits from friends and family and he could only communicate to them through letters which could be read by authorities.

The case languished for more than a year, finally getting underway in early September 2003. In an effort to weed out those who may have had preconceived notions about C-Murder and the music he was known for, prospective jurors were asked for their opinions on rap music and whether Corey’s stage name might adversely influence their verdict.

Following seven days of screening, an all-white jury was selected, and the trial began on September 17. In Freese’s opening statement, he told the jurors how Thomas idolized C-Murder and Master P, plastering his bedroom wall with pictures of them. Later, after the youth’s murder, his father, George Thomas, Jr., pulled all the pictures down, Freese explained.

Across the aisle, Corey Miller, alias C-Murder, sat passively at the defense table with Rakosky and his other attorney Martin Regan. No longer the snarling, defiant thug of his street persona, he was dressed conservatively in charcoal gray pants, a gray dress shirt and pearl gray tie. In his opening statement, Rakosky told the jury, “You will find Mr. Miller not guilty for the simplest of reasons. He did not kill Steve Thomas.” He called prosecution witnesses “unreliable and untrustworthy,” to which Freese countered that it was difficult to find witnesses willing to cooperate with authorities and testify against a celebrity with a fearsome reputation.

The first prosecution witness, Keshawn Jones, 20, emotionally testified that she knew Thomas from high school. Under questioning by Assistant D.A. Roger Jordan, she said she witnessed a melee in which Thomas was on the floor being beaten by some of the young men in Corey’s entourage. However, when Jordan asked what happened next, Jones refused to answer. Jordan then played an audiotape of Jones telling Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office Detective Donald Clogher that she saw a man she recognized as C-Murder pull out a gun, extend his arm and shoot Thomas in the chest. When asked if she had made that statement to Clogher, Jones hesitantly replied “Yes.”

In his cross-examination of Jones, Rakosky got her to admit she hadn’t actually seen the shooting and he told the court no murder weapon had ever been found, nor did any physical evidence link Corey to the crime.

Darnell Jordan, a security guard at the Platinum Club the night Thomas was murdered told the court that he saw the fight and said Corey was involved in it. Although he didn’t see a weapon in Corey’s hand, he saw a flash and heard a bang and, when asked if he was sure Corey pulled the trigger, Jordan replied, “There’s no doubt in my mind.” Jordan, who said he was standing near the club’s pool tables, testified that he saw Corey among a group of youths punching and kicking Thomas while he was on the floor. Jordan said he tried to break up the fight and was about five or six feet away from where the killing took place.

Initially, Jordan said he lied to investigators, giving a description of the assailant that didn’t fit Corey, because “I was afraid for my life.” Later that night, however, he told JPSO Deputy Kevin Nichols, who was working a detail at the club, that Corey was the killer. Living out of state at the time he gave his testimony, Jordan said he was no longer afraid to tell the truth.

Another prosecution witness, Eloise Matthews, told the court she had stood on a chair to watch the fight and she witnessed Corey and several of his friends beating Thomas. However, she said, she slipped off the chair and didn’t see the actual shooting.

On the third day of Corey’s trial, Tenika Rankins also told the court she had stood on a chair to see what the commotion was about at the Platinum Club. She said she heard Corey tell Thomas, “You don’t know who the f____ I am!” to which she heard Thomas reply, “I don’t care who you are!” She then said several of Corey’s friends, all dressed in black, began punching Thomas and she saw Corey reach under his shirt and extend his arm toward the under-aged youth. Although she didn’t actually see the gun, Rankins said she saw sparks fly from the end of Corey’s arm where a gun would have been. She said she had no doubt Corey killed Thomas. Rankins said Thomas was standing at the time he was shot, despite testimony from other witnesses that he was lying on the floor.

Inconsistencies in testimony given by prosecution witnesses now began to conflict. Rankins said she saw Corey enter through a VIP entrance and was not patted down for concealed weapons. John Young, a security guard on duty that night, said club policy mandated a weapons search and he was certain Corey had gone through the routine check like all other patrons. Even more glaring, however, was Keshawn Jones’ testimony when she was called back to the stand on the trial’s third day. She told jurors she implicated Corey because she was afraid the police would jail her for outstanding traffic tickets if she didn’t say what they wanted her to say. She then recanted and said she did not see Corey shoot Thomas.

On the fourth day of testimony, the prosecution was dealt another blow when it was revealed that a videotape at the club that might have recorded the murder had been taped over. Club owners Travis Mumfrey, Verrette Johnson and Gerald Harris initially denied Corey was in the club that night, according to Clogher’s testimony, but he ventured to guess that they might have been trying to protect themselves from civil liability. Clogher verified that no one who was interviewed that night explicitly fingered Corey as the killer, while admitting that several witnesses came forward that night to say Corey wasn’t the killer. Clogher even said that, while interrogating Corey, Corey said he had been talking to the club’s deejay when the altercation occurred. However, the deejay, Kirk Edwards, when called in to testify, didn’t recall talking to Corey that night.

After this testimony, the prosecutors rested their case.

On the fourth day, Master P came in for his first and only appearance during his younger brother’s murder trial, but he was not called to testify for either the prosecution or the defense. Outside the courthouse he told reporters, it was a case of mistaken identity. “It’s a shame they’re trying an innocent man. There’s no way my brother did what they said he did.”

On September 26, more than two weeks into the trial, the defense began calling its slate of witnesses. Five of them were paraded before the court, all of whom testified that Corey was not the one who shot Steve Thomas.

Keshawn Scott, Alvin Mitchell and Krystal St. Cyr all said they saw the fight and heard the shot but they were not sure Corey did the shooting. They all said he was not among the group that was beating Thomas and none of them could describe the shooter. Two other witnesses, Vance LeFrance and Vanessa Henry, went further by saying they saw Corey and he was not at the fight scene. However, LeFrance and Henry differed as to where they saw Corey at the time. None of the defense witnesses said they saw security personnel trying to break up the fight.

Of the five, only Henry said she knew who Corey was and all of them said they had no connection to the Miller family or any of its businesses. Under cross-examination, Henry said she heard some of the combatants shouting “Calliope” and “C-P-3,” obvious references to the housing project where Corey grew up. “C-P-3 was the name of one of his records.

When the trial resumed on Monday, September 29, the defense called four more witnesses — three men and a woman — to the stand. All of them vouched that Corey was not the murderer, though their accounts varied as to where Corey was when the fatal shot was fired. Hashim Smith said Corey was talking to the deejay and he made a brief announcement, plugging his latest album. Smith’s friend, Condell Sullen, tapped him on the hand and called his attention to the fight and the shot was fired seconds later, Smith testified.

Sullen testified that he didn’t hear Corey make an announcement but he said he saw the fight and concluded Corey wasn’t involved because all of the men beating Thomas were shorter than the 6’4″ Corey. Bianca Hansen testified that she saw Corey near the fight scene but he stepped away from it and couldn’t have been the one doing the shooting. The day’s final defense witness, Melvin Wilson, said he didn’t see Corey at all that night and he would have recognized him if he had been in the group fighting Thomas.

Following their testimony, the defense rested, setting up closing arguments the following day.

On October 1, following closing arguments by both sides, the jury retired to deliberate. Three hours and 40 minutes later, at 8:40 p.m., they filed back into the courtroom and solemnly announced their verdict. Corey Miller, alias C-Murder, was guilty of second-degree murder.

Corey’s family members and friends screamed and wept and fled the courtroom on hearing the jury’s decision. Corey himself showed no emotion. The verdict carried with it a mandatory life sentence with no parole.

Several friends of the Thomas family were seen smiling and using their cellphones to relay the verdict to other friends and family members as they exited the courthouse. George Thomas, Jr., the victim’s father, wept and told reporters, “Now my son can rest in peace.”

Freese told the media he was pleased the Thomas family “got the justice they deserved.” The lead prosecutor added that Thomas had aspirations of also becoming a rap star “but his innocence and naïveté clashed with C-Murder’s arrogance and cowardice.”

During closing arguments a few hours earlier, Freese had responded to what witness Rankins said she heard Corey tell Thomas, “Do you know who the f____ I am?” Freese told the jury, “Now you now know who he is. He is a killer and a murderer.”

Freese and co-prosecutor Roger Jordan called the jury’s attention to the conflicting stories of all nine of the defense’s witnesses. “They had him (Corey) all over the place,” Jordan said. They also praised the bravery of their witnesses for coming out against someone as popular and potentially menacing as C-Murder.

Rakosky countered that the prosecution had not proved Corey’s guilt and no physical evidence linked him to Thomas’ death. “The tragedy of losing a life cannot be undone by another injustice,” Rakosky told the jury. He also countered the prosecution’s argument that defense witnesses gave conflicting testimony, saying prosecution witnesses were also inconsistent in their testimony. “Why should defense witnesses be less worthy of belief?” he quizzed the jury.

Closing arguments had been interrupted for more than four hours when it was announced that the State Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals had ordered Judge Sassone to amend her instructions to the jury. Prosecutors asked her to read special instructions to the jury about considering the crime of manslaughter but she initially declined. Their reasoning was that juries unable to convict on second degree murder charges have the option of convicting on manslaughter charges, a lesser crime, but still one warranting a harsh sentence.

At the time the announcement was made about the Appeals Court ruling, Rakosky had just finished his closing argument. Following lengthy legal wrangling by both sides, the jury was duly informed and Rakosky was given a few extra minutes, during which he decried the “changing of rules in midstream.” But the long delay and the labyrinthine legal arguments that took place were for nothing as the jury opted for a verdict on the original charge — murder in the second degree.

The day after the verdict was announced, prosecutors in Jefferson and East Baton Rouge parishes said they would wait until Corey’s sentencing before deciding whether or not to proceed on the Baton Rouge charges against the rapper. East Baton Rouge Parish prosecutor, Brenda O’Neal, said she would wait for Corey to be sentenced before deciding whether or not to pursue the attempted first degree murder charges, which carry a ten to 50-year prison sentence. When asked about the logic of pressing other charges after Corey had already been sentenced on the second degree murder charge, O’Neal said another conviction could weigh against Corey before a Pardon Board in later years.

Also looming before Corey were the bribery, conspiracy and contraband charges stemming from the cell phone that was smuggled into his cell by the two now-dismissed Jefferson Parish deputies. Penalties ranged from 30 months to up to five years. Freese also announced he would wait for Corey to be sentenced in the Thomas murder before deciding whether or not to proceed on the cell phone-related charges.

Earlier, Rakosky had argued before the Louisiana State Supreme Court that the contraband charges against Corey should be dropped, because cellphone were not specifically listed under the statute’s definition of contraband. Those charges were eventually dropped, an act that prompted Sheriff Lee to persuade state legislators to add it to the list of items defined as contraband in jail cells.

Had he been sentenced, Corey would likely have been sent to the Louisiana State Prison in Angola. There he would have joined the ranks of Freddy Fender, Charles Neville, and other noteworthy fellow musicians who spent time in the notorious correctional facility along the Mississippi River, about 40 miles above Baton Rouge. However, Judge Sassone did not set a sentencing date right away, and defense attorneys immediately announced they would file motions for a new trial.

In the meantime, Sassone made a surprise decision on October 7 to call the jurors in the Thomas murder case back into court for a closed-door hearing. Having been placed under a gag order by Sassone, neither the prosecution nor the defense could comment on the reason for the unusual step, but it was the first hint that something might be amiss. Without being specific, Sassone’s law clerk Denise Chopin told reporters the closed-door session was requested by both prosecutors and defense attorneys to discuss “a preliminary matter that needed to be disposed of” before a motion for a new trial could be held in open court three weeks later.

Each juror was called into Sassone’s office, one by one, before they were all sent home. What was discussed wasn’t made public until more than three months later. However, it was reported that it had something to do with Sassone’s instructions to the jury, following their verdict, not to discuss the case with anyone. Usually after a verdict is announced, jurors are then free to discuss the cases in which they served. During this out-of-the-ordinary procedure, Corey was brought into the nearly empty courtroom in his orange prison jumpsuit where he conferred with Rakosky and Regan before being returned to his cell.

Less than two months later, on December 12, another surprise was sprung. One of the key prosecution witnesses, Eloise Matthews, was now saying that she saw someone other than Corey with the gun on the night of the Thomas murder and that she had only been saying what she thought the police wanted to hear. She said she tried to tell them it was a man known as “Calliope Slim” who had the gun, but “the officers did not want to hear that.” She admitted seeing Corey in the group of men punching and kicking Thomas but denied he was the shooter. When asked by Freese why she didn’t reveal the information about “Calliope Slim” when she testified at the trial, she replied that no one had asked her. Matthews did, however, reveal that she had gotten threatening phone calls warning her not to testify.

Corey’s attorneys were claiming that some of the prosecution witnesses had criminal records which the prosecution had withheld from the defense. Had they known this at the trial, Rakosky maintained, they could have used this information to discredit the witnesses and their credibility. The defense team also argued that the authorities agreed to do favors for prosecution witnesses in exchange for their favorable testimony, among which included the expunging of witnesses’ records of criminal activity.

Rakosky said that another prosecution witness, Matthews’ friend Tenkia Rankins, had a prior conviction for shoplifting that was expunged, implying that it might have been done in exchange for her testimony. Freese countered that he would have had no way of knowing about the conviction if the record had been expunged. Rakosky also told the hearing that Matthews had a felony theft arrest and that fact was also withheld from the defense.

Freese countered that the allegations were untrue. “During the trial, Mr. Miller tried to evade responsibility for his actions but twelve jurors disregarded that attempt. What we are seeing now is simply more of the same.” He also said he expected to call witnesses to rebut the defense allegations when hearings resumed on January 15, 2004.

It was also revealed that Matthews had a shoplifting conviction and was placed in a diversionary program aimed at first-time offenders giving them a chance to clear their name. Freese claimed the defense knew about this, but Rakosky countered that she had been kicked out of the program and the prosecution never informed the defense of this.

Also at the hearing, Verrett Johnson, one of the Platinum Club owners, testified that security guard Darnell Jordan told him at the time he didn’t see the shooting. This also ran counter to what was said at the trial when Jordan testified that he saw Corey fire the shot.

The court then recessed for the holidays, with hearings to resume on January 15.

The surprises continued when hearings on Corey’s retrial bid resumed in mid-January. Christina Langlois, an employee of the Louisiana State Police Criminal Identification Bureau, told Judge Sassone that the records of key prosecution witness Tenika Rankins for felony theft in 1997 were not expunged until November 2003, nearly two months after Corey’s conviction. Raksoky used this as ammo for his contention that the prosecution withheld key information from the defense about its witnesses’ criminal backgrounds, as required by state law. He used Langlois’ admission in his press for a new trial for Corey. Freese continued to maintain that he knew nothing of Rankins’ conviction.

Efforts to locate Rankins before the hearing were unsuccessful.

Six days later, during another hearing, JPSO Detective Donald Clogher admitted he had assisted the prosecution in getting a new court date for Rankins to resolve her outstanding traffic tickets. However, Clogher denied doing any special favors for Rankins, other than to offer her protection because she was scared of possible repercussions from testifying against Corey. Rakosky contended that Rankins’ expungement was improper because she had a misdemeanor theft charge pending against her in neighboring St. Charles Parish.

Clearly frustrated by Matthews’ contradictory testimony, Freese told her and the court she could be charged with perjury.

Rakosky dropped another bombshell when he announced that jurors were overheard discussing Corey’s arrest for attempted murder in Baton Rouge during their deliberations at the end of the trial. Sassone had earlier ordered that jurors were not to be told of the Baton Rouge charge. At that point it became public knowledge that that’s what had been discussed when Sassone called the jurors back for private conferences on October 7.

Final written arguments by both sides were submitted to Sassone on February 19 and, on March 2, the defense wrapped up its effort to win a new trial for Corey. In oral arguments, Rakosky summarized the case he was making on behalf of his client: that Corey deserved a new trial because of improprieties on the part of the prosecution. He cited their alleged failure to notify the defense about their witnesses’ criminal backgrounds as one of the main reasons.

“The jury had a right to know about these things,” Rakosky told Sassone. Freese contended that he didn’t know about Rankins’ problems with the law because her record had been expunged. However, he maintained that the defense knew about the criminal records of other witnesses and chose not to question them about it during cross-examination.

Rakosky also said that security guard Darnell Jordan “was a wanted man” when he testified, with an outstanding warrant for a moving traffic violation. Freese said that Jordan got the ticket just before the trial and the prosecution did no special favors for its witnesses.

Following the conclusion of oral arguments, Sassone promised a ruling within a reasonable time. But, she added her belief that the side that loses will probably file an appeal and that would extend the overall decision-making process.

On April 6, Sassone issued her long-awaited decision. Almost exactly half a year after his conviction, Corey Miller, alias C-Murder, was awarded a new trial. Agreeing that the prosecution withheld key information from the defense, she overturned Corey’s September 30 conviction and ordered a new second degree murder trial for him.

While Corey’s attorneys rejoiced and sought to get him released on $2 million bond, Freese immediately announced he would appeal Sassone’s ruling to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal. Freese asked that all proceedings, including the bail hearing, be postponed until the Appellate Court conducted its review. Sassone declined to elaborate on her reasons for the ruling because the matter was going to be under appeal.

Several days later, Sassone ruled that Corey was being denied bond because of the pending Baton Rouge case. She also wanted to wait at least 30 days to see if the Fifth Circuit ruled on Freese’s appeal. Rakosky offered to put up $2.8 million in Miller family property in Baton Rouge as security but the offer was declined.

Percy Miller Sr., father of Master P and C-Murder, told reporters he was happy Corey was getting a new trial but angry over the bail denial. “Corey should be walking out here with us today. Corey Miller is innocent of any crime,” the father maintained, adding that Freese “should burn in hell” for prosecuting his son. Freese had no comment on Miller Sr.’s remarks. The victim’s father, George Thomas, Jr., expressed his displeasure at having to go through another trial.

Following Sassone’s ruling for a new trial, Freese announced publicly for the first time that Corey was being charged with battery on a correctional officer. The incident allegedly occurred while Corey was in jail awaiting trial. Sassone set a June 14 date for a hearing on that matter, but the charges were later dropped when the deputy resigned from the department and declined to testify against Corey.

For the remainder of 2004, Corey’s case dropped from the public radar as attorneys for both sides prepared their cases for the retrial. However, in early 2005, he resurfaced as C-Murder in a big way: as the star of a new 17-track CD and music video, recorded and filmed in the Jefferson Parish Correctional Center. It was released on March 22 but previews of it were available a month earlier.

Entitled “The Truest S**t I Ever Said,” the CD/video was an instant hit, C-Murder’s first new release since just before his Baton Rouge arrest four years earlier. Featured on the cover was a picture of the bare-chested rapper pointing accusingly at the camera in front of the Calliope Project. True to its title, the CD did indeed feature some of C-Murder’s strongest lyrics to date.

In the music video made for the CD’s opening track, “Y’all Heard of Me,” Corey is seen in his orange prison jumpsuit, gesturing wildly with his hands while rapping. The video was inter-cut with scenes from around inner city New Orleans, including the Calliope Project, as well as shots of other rappers, crowds and street scenes. Rakosky appears in the video, confirming that the shots of Corey were taken from interviews arranged with Court TV and a local Cox Communications cable TV program, “Phat Phat ‘n’ All That,” a regular program that features rap artists and their videos. However, spokespersons for both sources denied that permission had been granted for use of the footage shot inside the prison.

The CD, released on the New York-based Koch label, was reviewed in the July 2005 issue of OffBeat, a monthly magazine that focuses on New Orleans and Louisiana recording artists and the music scene. Reviewer Robert Fontenot called it “the best CD of (C-Murder’s) career,” despite the irony of the clandestine methods used to record it. National music publications gave it similar rave reviews. C-Murder remained a top-name rap star, despite his confined circumstances. Some even speculated that the charges against him only added to his celebrity status.

The making of the CD and video stirred debate on whether convicted criminals should be allowed to profit from their creative products — whether they be books, movies, recordings or videos. Several states, including Texas and California, prohibit this but Louisiana does not. Jefferson Parish District Attorney Paul Connick, Jr. (a cousin of musical superstar Harry Connick, Jr.) confirmed that no laws were broken in the release of Corey’s CD/video.

The release of C-Murder’s new project drew the immediate wrath of Jefferson Parish’s powerful and notoriously outspoken sheriff, Harry Lee. Never one to mince words, Lee, a self-styled “Chinese-American Cajun Cowboy,” who has held the post since 1980, had gotten himself in hot water several times in the past with racially charged remarks in his overwhelmingly white, suburban parish. He once made international headlines by announcing that young black men cruising predominantly white neighborhoods “in rinky-dink cars” would be stopped and challenged by his deputies. Although his racial profiling policy was blasted by black activists and civil rights organizations, it added to his popularity among his constituents. He has been reelected six times, rarely against serious opposition.

“Nowhere was it ever mentioned that someone would be doing a commercial enterprise in the jail,” Lee said. “I am pissed off that an attorney would trick me,” he added, accusing Rakosky of aiding Corey in producing the CD/video in the jail without his permission. He alleged that the attorney smuggled in recording equipment for his rapper client and smuggled out copies of lyrics. Then Lee began demanding that the sheriff’s office be given a percentage of the releases’ royalties. “They used my jail. I think I’m entitled to some money,” Lee said.

Rakosky countered that Lee, himself, had permitted Corey to be interviewed by news crews from two TV shows, and much of that footage was included in the music video. He admitted to having given Corey encouragement to do something with his otherwise idle jail time, and defended his client for using his time productively and creatively in the making of the CD/video. He admitted to recording about five hours of Corey rapping on tape. He also said that portions of the recording process were witnessed by jail personnel — sheriff’s deputies — and none of them indicated Corey was doing anything improper.

Apparently still seething over what he perceived as an act of deception, Lee announced that Corey would be allowed no more TV interviews, including a request from MTV. He ordered Rakosky to bring nothing more than a pencil and notepad to further in-cell meetings with Corey, saying that hollow pens could be used to smuggle out song lyrics. Rakosky challenged this, saying there were times he would need to bring his files on the case to the jail. In a consent judgment issued by Sassone, Rakosky was allowed to bring case documents to the jail but she agreed with Lee’s decision to require him to use a pencil. Rakosky grumbled but declined to make a further issue over it.

At the time all of this was going on, the Appellate Court had still not ruled on the prosecution’s appeal of Sassone’s ruling on a new trial. Finally, on March 10, 2005, a ruling was handed down. Sassone’s decision was overturned by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal. Sol Gothard and Clarence McManus, two of the three appellate judges hearing the appeal concurred that, even without the testimony of the witnesses, there was abundance of other evidence which fully established Corey’s guilt. Judge Thomas Daley disagreed, citing the recanting of one witness’ testimony and adding that Sassone, as trial judge, was in a better position than the appeals court to make the decision on granting a new trial.

D.A. Connick announced that the ruling set the stage for a sentencing hearing for Corey nearly a year and a half after his original conviction. He hailed the appeals court’s decision, although he said he expected their ruling to be appealed by Corey’s lawyers.

Needless to say, this wasn’t the present Corey was hoping to get the day after his 34th birthday.

Now it was the defense’s turn to appeal the ruling and the only place they could go with it was to the Louisiana State Supreme Court. Rakosky did not immediately commit to taking that course but he hinted that it was one of several options they could explore. Another would have been to let Sassone sentence Corey, then appeal the sentencing to the same appellate court “on a broader range of issues,” including what he called “the systematic exclusion of black jurors,” in addition to the prosecution’s withholding of background information on its witnesses.

However, on March 25, Rakosky took the unusual step of asking the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal to revisit its decision of earlier that month. He filed a brief in which he said “it is virtually unheard of in Louisiana that an appellate court would reverse a trial court’s decision in the absence of an abuse of discretion,” such as a ruling not based on the facts of the case. He asked that at least five appeals court judges or perhaps even the full nine-member bench re-hear the case

Within four days, Rakosky had his answer. The appeals court would not go back on its earlier ruling. The declined to re-hear the case without offering an explanation.

Left with no choice, Rakosky decided to take it to the top and appeal the appeals court ruling to the Louisiana State Supreme Court. In announcing the decision, he said the actions of the appeals court would factor very heavily in the case they would make before the state’s highest judicial body.

“We will be filing with the Supreme Court within the allotted time to reverse the Court of Appeals decision and reinstate the ruling of Judge Sassone,” Rakosky announced. A week later, support came from an influential quarter. The Baton Rouge Chapter of the NAACP entered the fray, saying that Corey’s civil rights were being violated by the appeals court’s refusal to re-hear the case, and they sued the state of Louisiana on his behalf.

By this time, Corey announced that he was no longer using the name C-Murder. To soften his bad-boy image and influence future courts and juries, he said he would be using the name C-Miller. “People hear the name C-Murder and they don’t realize that the name simply means that I have seen many murders in my native Calliope projects neighborhood,” the rapper stated. “From the beginning, I have been a target because of who I am, my stage name and for my success as an entertainer and the success of my siblings,” he said in prepared statement issued through the Koch record label.

Over the next several months Corey’s attorneys prepared their appeal to the State Supreme Court, based in an imposing white marble building on Royal Street in New Orleans’ historic French Quarter. However, on August 29, Hurricane Katrina hit the city with powerful winds and flooding from breached levee floodwalls. Even though the solid structure housing the Supreme Court was largely spared, as was most of the French Quarter, the judicial system of southern Louisiana came to a virtual standstill, along with nearly every other state agency and private business. Power remained out in the city for weeks. Along with approximately 1,100 other inmates in the Jefferson Parish jail, Corey was transferred to other state facilities farther inland that were not impacted by the storm.

Finally, on February 21, 2006, with service restored to most state and city agencies, Corey’s lawyers filed their appeal with the State Supreme Court. Rakosky was now joined by noted criminal defense attorney, Robert Glass, who had a history of getting celebrity clients off the hook, including California feminist Ginny Foat on a murder charge in Jefferson Parish in 1983.

Corey was not present when Rakosky and Glass filed their brief during a hearing, but nearly a dozen relatives and supporters were there for him. Arguing a persuasive case, Glass told the state’s high court justices that prosecutors had “no physical evidence, no conclusive evidence” that Corey shot Thomas. He called one of the prosecution witnesses “a through and through liar… and the jury didn’t know that.”

Glass also reiterated positions that had been brought up in earlier rulings; that prosecutors hadn’t fully shared information about witnesses’ criminal backgrounds with the defense. Jefferson Parish Assistant District Attorney Juliet Clark countered that her office had shared what it knew at the time with defense lawyers.

Unlike his birthday the year before when the appeals court shot down Corey’s request for a new trial, he finally got the birthday present he wanted when the State Supreme Court granted the defense’s request two days after Corey turned 35.

Corey was in the Concordia Parish jail in Ferriday, Louisiana when he received the good news. Ironically, this was the hometown of rock and roll pioneer, Jerry Lee Lewis, also considered a musical “bad boy” in his late-1950s heyday.

In its four-page order, the state’s highest court reinstated Judge Sassone’s ruling that granted Corey a new trial. They said Sassone’s 20-page order “reflects a painstaking review of the evidence presented at trial and in the course of 13 post-conviction hearings, during which she became convinced that one of the state’s principal witnesses was ‘someone who is accustomed to lying.'” The justices also noted that Sassone “did not act arbitrarily or capriciously (in issuing her retrial order) but exercised her authority” under state law to grant Corey a new trial.

On hearing the high court’s decision, Rakosky immediately announced that he would seek Corey’s release on bond. With no retrial date set, the attorney said he didn’t think his client should remain locked up indefinitely any longer. Connick had no immediate comment on the Supreme Court decision, nor did he say whether or not his office would pursue a new trial against Corey.

Finally, on March 21, 2006, for the first time in more than four years, Corey Miller walked into a courtroom unshackled and without an orange jumpsuit. Accompanied by Rakosky and several family members, he entered Sassone’s Division K courtroom well-groomed with dark suit pants, a light blue shirt, a white tie and aviator glasses. There he would be notified about his bail and the terms of his temporary release.

A week earlier, over the objections of the Jefferson D.A.’s office who still considered Corey “dangerous,” Sassone had set bail at $500,000. Corey would be essentially placed in a “home incarceration” program at the home of his grandmother, Maxine Miller, in the New Orleans suburb of Kenner. His movements and communications would be strictly monitored by law enforcement authorities. The judge set limits on who Corey could have as visitors and who he could talk to on the telephone. Parties weren’t allowed. Neither were interviews with the media. Corey would have to submit to random drug screenings. Only immediate family members could visit the house, in addition to Corey’s attorneys and in-home care workers who assist Maxine. Anyone with a felony conviction would not be allowed. Corey could only leave the property for court dates or meetings with his legal team.

“These are very stringent rules, and one infraction is going to result in revocation of your bond,” Sassone warned Corey during the brief hearing. “I hope you’re going to adhere to these rules.”

“I understand, your honor,” Corey replied softly.

With no retrial date having been set on the Steve Thomas murder, Corey Miller, formerly known as C-Murder, remains in home incarceration and under close observation. There is speculation that the Jefferson Parish D.A’s Office may opt to not try Corey again since most of the prosecution witnesses have been discredited, which would mean that Corey would be a free man.

However, he is not out of the woods yet. He may have other troubles on his plate in the months to come. On March 17, Judge Anthony Marabella of the 19th Judicial District Court in Baton Rouge set bail at $250,000 in the attempted murder charge stemming from the incident at Club Raggs nearly five years earlier.

That case is set to be heard May 30, 2006, and it is believed to be a stronger case than the one built by the Jefferson D.A.’s Office, with witnesses and videotaped evidence. The world will be watching this case, anxiously awaiting the outcome.

The district attorney’s office in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana is attempting to return Corey Miller, the rapper formerly known as C-Murder to jail. At the same time, the daily newspaper in New Orleans is going to court to try and obtain sealed documents related to the case.

These are among the latest developments in the case in which Miller was convicted by a Jefferson Parish jury but has been granted a new trial on legal technicalities. On October 1, 2003, Miller was found guilty of second-degree murder in the death of 16-year-old Steve Thomas at a nightclub in Harvey, Louisiana, on January 14, 2002. However, the presiding judge in the case, Martha Sassone, later ruled that vital information had been withheld from the defense by the prosecution.

Several key prosecution witnesses reportedly had criminal records, which Miller’s attorneys said they weren’t given during the trial. Sassone agreed that this could have made a difference in the case’s outcome and she ordered a new trial for Miller. An appeals court overturned her decision and finally the Louisiana State Supreme Court reinstated it. No new trial date has been set.

On March 21, 2006, Sassone granted the defense’s request that Miller be released on $500,000 bond into a “home incarceration” program. He would be allowed to stay at his grandmother’s house but heavy restrictions were placed on his movements and visitors. The only time he would be allowed out of the house was for court dates or to meet with his attorneys. Only close family members, his lawyers and a priest were allowed to visit him or talk to him on the phone. He was ordered to wear a tracking device that allowed the authorities to monitor his movements and he had to submit to random drug tests. No parties or interviews with the media were allowed.

While Miller’s trial was going on there were reports that he was using a cell phone smuggled into his jail cell to threaten potential witnesses who claimed to have seen him shoot Thomas. During his home incarceration the court was trying to make sure he didn’t have an opportunity to do that again or communicate with anyone else with that objective in mind.

Two months later, however, Miller was again in court for a 90-minute hearing that was closed to the media and the public for all but a few minutes. The initial report that emerged from the hearing was that Miller had violated the terms of his home incarceration. No details could be reported in the May 25 edition of the Times-Picayune the day after the hearing. Sassone had imposed a gag order on both the prosecution and the defense, as well as on the family of the victim, members of whom had been at the hearing. The only new revelation was that Sassone had revoked the house arrest order on May 8, but after leaving the courtroom on the 24th, Miller returned to his grandmother’s house, so apparently there had been a change in the decision.

On June 9, the Times-Picayune reported that the Jefferson Parish D.A.’s office was seeking to return Miller to prison. This time the details were a bit more specific. According to the motion filed by prosecutor Roger Jordan, Miller had stopped at a Smoothie King store on May 4, on his way back from a court-approved outing, a violation of the terms of his home incarceration. On that same day he was supposed to be back home by 12:30 p.m. but didn’t return until after 4:00. He was also reportedly with his fiancée, Sabrina Green, that day without court authorization.

In addition, prosecutors contended that Miller was “out of range” of his electronic monitoring equipment on at least two occasions on May 31 and June 1 for 44 and 27 minutes, respectively. Miller, who earned millions of dollars from the sale of his records both before and after his arrest, also reportedly fell behind on his $50 a week home incarceration fees.

Miller was in the process of being taken to the Jefferson Parish jail when Sassone intervened and ordered him returned home, according to unnamed sources quoted by the Times-Picayune. When Miller appeared in Sassone’s court on June 6, he was ordered to pay his home incarceration fees in advance and police were ordered to “recalibrate” the electronic monitoring system they used to track Miller’s movements.

On June 14 Sassone ordered Miller’s case records sealed, and formally issued a gag order “preventing all counsel and parties from discussing or divulging any aspects of this case with anyone not a party. Two days later the Times-Picayune filed documents in Jefferson Parish’s 24th Judicial District Court challenging Sassone’s decisions.

The newspaper sought access to all documents related to the case and attempted to compel Sassone to hold all proceedings in the case in open court. Most of the proceedings had been held in the privacy of her chambers. “Proceedings which are held in secret and without the light of publicity create a suspicion that evenhanded justice may not be administered,” the newspaper’s attorneys wrote in their motions. They also contended that Sassone’s order to seal Miller’s records “violates the public’s right of access under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution,” as well as federal and state laws.

The Times-Picayune sought to have Sassone consider their arguments before a hearing on Miller’s home incarceration that was scheduled for June 20. That hearing was postponed.

In the meantime, Miller remains charged with attempted murder in a separate case in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. On August 14, 2001, Miller was accused of attempting to fire a gun at a security guard and the owner of a Baton Rouge nightclub where he was turned away. Miller reportedly refused to submit to a search for concealed weapons and, when ordered to leave, he allegedly attempted to shoot the guard and the owner who had been called onto the scene. Miller’s gun reportedly misfired before he managed to squeeze off a shot that went harmlessly into the floor. The incident was captured on videotape, according to reports.

After a warrant was issued for his arrest, Miller turned himself in and was released on $100,000 bond. He has yet to stand trial on those charges. A hearing scheduled for May 30, 2006, was postponed indefinitely.

In another development in the five-year-long C-Murder saga, the February 26, 2007, retrial date for Corey Miller set by Judge Martha Sassone was postponed indefinitely.

The decision by the Jefferson Parish District Attorney’s Office to go ahead with the retrial had put to rest doubts that they would proceed in light of the discovery that the prosecution, during Miller’s 2003 trial, had failed to disclose to the defense the criminal records of key witnesses who had claimed to have seen Miller shoot Steve Thomas. This oversight led Judge Sassone to order a new trial for Miller.

Prior to their decision to proceed with the retrial, it had not been known if the prosecutors still planned to use the same witnesses who had testified against Miller in the first trial. Ron Rakosky and Robert Glass still remain Miller’s attorneys of record. Assistant DAs Roger Jordan and David Wolff are expected to make the state’s case against Miller.

Before retrial date was initially set, however, some developments unfolded that left the New Orleans media and local observers scratching their heads in puzzlement. Sassone, widely known as the tough judge who had once sentenced a convicted armed robber to 792 years in jail, inexplicably eased Miller’s home incarceration restrictions, even though he had reportedly violated the program’s terms on a number of occasions.

In a hearing on July 13, 2006, prosecutors had sought to have Miller removed from the home incarceration program and returned to the Jefferson Parish Correctional Center for the program violations, including being out of range of monitoring devices for extended periods of time, stop-offs at unauthorized locations while outside his home, and having unapproved visitors at the home, including his girlfriend. However, instead of approving the prosecutors’ recommendations, Sassone went in the opposite direction and gave Miller more leeway than he had previously.

Sassone ruled that Miller no longer had to wear the monitoring device on his ankle and could move about freely anywhere within Jefferson Parish and New Orleans, as long as he remained at his grandmother’s home between 10:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m. He was forbidden to go to bars or drink alcohol, and there were still restrictions on the visitors he could have at home, but apparently his girlfriend was not one of those restricted. She was with him at the July 13 hearing and left the courtroom with him and family members after Sassone had issued her ruling.

Among the reasons Sassone cited for releasing Miller from many of the restrictions of home incarceration was the “burden” they had placed on those in charge of monitoring the program. After the decision was reported in the media, it drew a very vocal objection from Chief Arthur Lawson of the Gretna Police Department, which oversees the program. Lawson was quoted in the Times-Picayune as saying, “We certainly don’t feel that it was a burden. It certainly wasn’t the sentiment of our officers, the office, or the program.” Lawson’s comments did not become public for more than a week after Sassone’s ruling because the prior gag order she had imposed on the case was only lifted days earlier.

Sassone’s decision to loosen the restrictions on Miller had many others baffled and angered, including several Times-Picayune columnists and writers of letters to the editor. One letter writer called it “a slap in the face” of the police and the citizenry and suggested that, “Judges who make these stupid decisions… must be removed from the bench.” Another letter writer called the ruling “frightening and infuriating.”

Writing in his July 26 column in the Times-Picayune, James Gill noted, “The worse Miller behaves, the more favors he gets… Either Sassone has flipped her lid, or she is subject to some malign influence. Her rulings in the case grow increasingly bizarre.”