Candy Barr: America’s First Porn Princess — The Big D — Crime Library

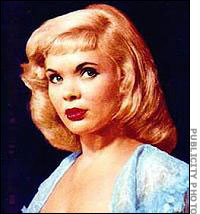

Juanita Dale Slusher pranced into Dallas in 1949 as a wide-eyed 13-year-old runaway with a baby-doll face, but with a body that would make Bettie Page blush.

She was a Texas hayseed from a dusty town 300 miles south of Dallas, and the Big D saw her coming.

The junior-high dropout worked as a hotel chambermaid just long enough to learn that there were other ways to make money with mattresses.

She married at 14, but prison bars came between Juanita and her teenage husband, whose primary skill was taking things that didn’t belong to him.

She had to eat, so like many down-and-out divorcees she found her way to the naughty nightclubs of Commerce Street in downtown Dallas.

Juanita sold cigarettes and served cocktails to the men who visited the clubs for adult merriment — businessmen in town from Houston or Oklahoma City, ranchers up from Waco, college frat boys on weekend wing dings.

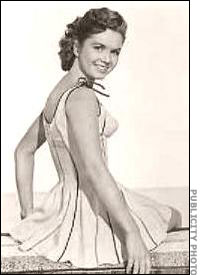

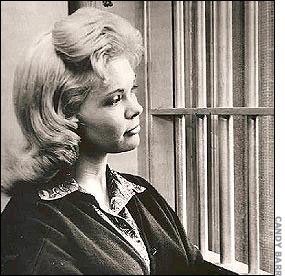

The pert teen, an athletic five-foot three-inches, became a favorite of the butt-pinching set. She colored her brown hair platinum and used giggles and wiggles to induce pickled fellows to tuck astonishing tips in her smock pockets.

Every customer had a come-on, and she would flirt back. At the end of the night, most of them got a peck on the cheek and a pat on the head. But a few particularly generous customers got a roll in the hay — more Texas hospitality than prostitution.

One patron played his angle hard. He said he was a film director, and he convinced Juanita of her movie-star potential. She should have been skeptical when the screen test turned out to be not in Hollywood, but San Antonio.

Slusher won film stardom, all right. She was the female lead of a silent stag film, Smart Alec, the story of a nubile teenager, a horny traveling salesman, and a busy motel bed.

The 20-minute blue romp — filmed when she was 16 — earned Juanita Slusher the title of America’s first porn princess.

But that was just the beginning of a life lived on the front pages.

She had a long, profitable career as a marquee stripper. She canoodled with the rich and famous, including an infamous mobster. A marijuana arrest made her a touchstone figure in the “Reefer Madness” of the 1950s. As a confidante of Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby, she was interrogated by authorities about the assassination of President Kennedy.

She was a bravely independent woman, and she took on anyone who crossed her, from the drunken, abusive husband (one of four) that she shot in the groin to the cops she believed set her up for the pot bust.

Late in her life, as pornography shifted toward the mainstream of American popular culture, she became an iconic figure among sex workers, modern burlesque dancers and those who enjoy the services of those occupations.

Oh, yes: She was also a published poet.

Annie Sprinkle, a former stripper and porn star, describes Juanita Slusher as a “great sex goddess and artist.”

Sprinkle and others told the Crime Library that Juanita was a groundbreaking exotic entertainer who paved the way for the “sex-positive” feminism that emerged in the 1980s and for the American sexual emancipation that led to the mainstreaming of sexuality.

Not long before she began her burlesque career, Juanita picked up a nom-de-striptease that ensured her a place among the world’s most widely recognized exotic dancers, alongside Salome, Gypsy Rose Lee, Tempest Storm, Blaze Starr, Mata Hari, Chesty Morgan and Fanne Foxe.

Juanita Dale Slusher, who had a typical teenager’s sweet tooth, became known on stage as Candy Barr.

Juanita came from Edna, in the south Texas cotton, cattle and oil country, halfway between Corpus Christi and Houston, each 100 miles away. Hot and dry, Edna was a county-seat city of 3,000 when she was growing up.

It was not an idyllic small-town childhood.

Juanita was a Depression-era baby, born in 1935, about the time a boll weevil infestation was ruining the region’s cotton crop and driving people off their farms.

She was molested by the older boy next door. When she was nine, her mother was killed when she fell out of a moving car. Her father, a bricklayer known by the nickname “Doc,” brought home a new wife whose pastimes included whipping the stepchildren.

Juanita had a knack as a singer and dancer — the sort of talents that might draw a schoolgirl toward cheerleading for the Edna High School Cowboys.

But she quit ninth grade and ran away to Dallas, where the brief marriage to Billy Joe Debbs preceded her Commerce Street career and the featured role in the silent, black-and-white smoker film.

There wasn’t much of a plot to Smart Alec, even by porn-film standards.

A traveling salesman (the actor’s identity has never been determined) meets Juanita’s character at a motel pool. He entices her back to his room, where vigorous fornication ensues. When the man seeks oral sex, she demurs and calls upon a female friend to help out.

Happy endings all around. Fade to black.

In that era, porn was bought under the counter in 8mm or 16mm reels, and then played on private projectors at poker nights, boxing smokers, stag parties and frat houses.

Smart Alec became one of the most popular early porn films, the Deep Throat of its day. One film critic, Phil Hall, calls it the Citizen Kane of stag films.

In their book Dirty Movies, which traces the history of stag films, authors Al Di Lauro and Gerald Rabkin called Smart Alec “the single most popular film of the genre.”

At the time, many blue films were homemade productions that featured pimps and the prostitutes who worked for them. With few exceptions, the stars were haggard and saggy, if not downright nasty.

The appeal of Smart Alec was due entirely to Juanita, the leading lady. She was uncommonly attractive for porn, and she seemed to be enjoying herself.

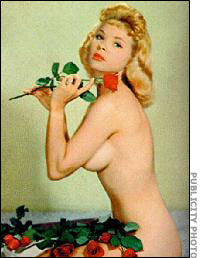

“Viewing ‘Smart Alec’ today,” wrote critic Hall, “one can see…why this film was so popular. The first reason was Candy Barr, who was clearly the most gorgeous woman to appear in pornography. Let’s face it — most porno stars do not look like movies stars. Barr looked like she belonged in Hollywood — she was very pretty, had a great body (38-22-36), and clearly had a vibrant personality that connected with the camera. It was difficult to imagine that she was 16 when she made the film.”

Juanita’s body became a hot commodity when she returned to Commerce Street after the film shoot.

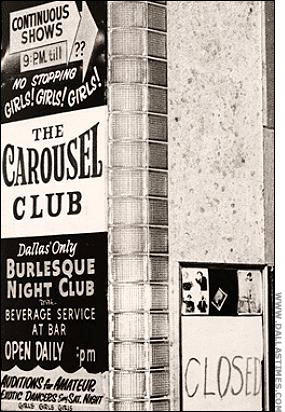

Commerce runs parallel to Main Street in the heart of downtown Dallas. The strip was a magnet for out-of-towners with heavy wallets, drawn to venerable hotels like the Adolphus and the Magnolia. Nightclubs like the Century Room, the Theater Lounge, the Carousel and the Colony Club vied for these customers, offering nightly variety shows — the next generation of Vaudeville — that included comedy, live music and stripping.

Juanita had her pick of the clubs as she graduated from cocktail waitress to star stripper. She took an $85-a-week gig at Abe Weinstein’s Colony Club, at 1322 ½ Commerce St., which had a more civilized reputation than Jack Ruby’s Carousel, two doors down.

It was Weinstein who gave Juanita the stage name that made her famous. He said that he was looking for something sexy and catchy, like Tempest Storm, but came up with the girlish Candy Barr because the teenage Juanita craved confection.

And Dallas soon began to salivate over Candy.

She became a regular in Tony Zoppi’s “Dallas After Dark” column in the city’s Morning News. While trawling the Big D at night, Zoppi handicapped club strippers as though they were thoroughbred horses.

One dancer, he wrote, was green on stage but possessed “the equipment for much bigger things.”

Candy Barr was often compared with another pert native Texan who became famous in the 1950s, singer/actress Debbie Reynolds.

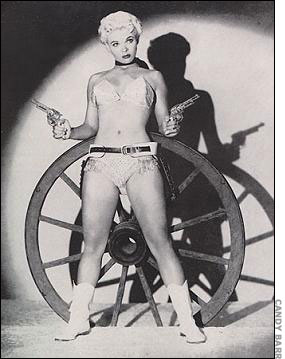

But Candy’s wardrobe was something different.

For her signature striptease, she would walk on stage wearing a full Annie Oakley buckskin get-up. By the time her five-minute routine was up, she would have stripped off everything but her panties, pasties, cowboy boots, white cowboy hat and the twin holsters slung low across her hips.

For her finale, she would fire her cap guns in the air as the lathered-up crowd erupted into rebel yells of “yee-haw!”

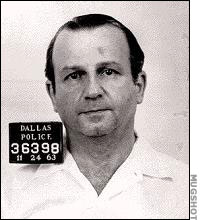

Offstage, Candy enjoyed hanging out at the Carousel after hours, where owner Jack Ruby became a close friend and father figure. She couldn’t have known that he, too, would be famous one day.

Candy Barr tried marriage again in 1953 when she hooked up with Troy Phillips, a nightclub denizen who became her husband and manager.

They managed to have a daughter in early 1955, in between fights.

The Colony Club missed Candy desperately while she was gone on pregnancy leave. Abe Weinstein lured her back with a three-year contract at a stunning $2,000 a week. The baby was shipped home to Edna, Texas, where she was raised by relatives, and Candy enjoyed a profitable stretch as a $100,000-a-year stripper.

But her bump-and-grind career hit a chuckhole.

Her marriage to Phillips had fallen apart by the holiday season in 1955. Candy filed for divorce and moved into her own apartment in the Oak Cliff neighborhood, but Phillips was not the sort to walk away without one last dustup.

On Jan. 28, 1956, Candy had finished her shift at the Colony and was tucked in bed when the phone rang at 3 a.m. The caller hung up when she answered.

A couple of hours later, Phillips showed up at her door. When Candy refused to let him, he kicked in the door and stumbled drunkenly around her apartment.

Candy said she warned Phillips that she had a gun and would use it. She grabbed a .22 rifle from a closet and fled the apartment.

Phillips stalked after her, making the bizarre demand that she kowtow to him by lighting his cigarette.

“I’m going to make you light my cigarette,” she quoted him as saying, “and then I’m going to beat you.”

When he got six feet away, she leveled the rifle barrel on her husband and pulled the trigger. She hit in the lower belly, near the groin. She said her aim was off. She missed high.

The story was a front-page sensation in Dallas, where the papers frothed about the “shapely blond nightclub entertainer.”

Colony Club owner Weinstein showed up at the police station to throw her $10,000 bail. The publicity bonanza was not lost on him.

“We’re already having standing-room crowds,” he told news scribes. “This’ll mean we’ll have to turn more customers away.”

The charges were dropped two weeks after the shooting, when Phillips acknowledged that he’d been drunk and ornery.

By the time the shooting played out, everyone in Texas knew Candy’s name.

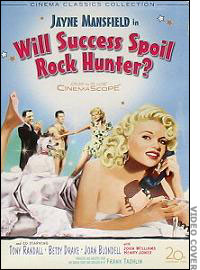

Robert Glenn, a producer with the Little Theater in Dallas, seized on her fame in 1957 by casting Candy in the featured role of Rita Marlowe — played on Broadway and on film by Jayne Mansfield — in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?

Tony Zoppi, the Dallas Morning News‘ intrepid nightclub reporter, wrote that the producer found Candy Barr to be “the logical choice” for the role, which keys on the sex appeal of a lipstick model.

Candy told Zoppi, “It’s quite a challenge, but I’ll do my best. I’ve always had an ambition to do a stage play, and this one seems especially suited for me.'”

She got through the brief run, but further legitimate roles did not materialize. It was her first and last stage job that did not require the removal of her clothing.

But she did get dozens of fresh offers to strip, and she branched out by taking high-paying special guest gigs at clubs in New Orleans, Las Vegas and Los Angeles.

While in Hollywood, she hired on as a consultant to actress Joan Collins, who was studying for a role as an exotic dancer in the film Seven Thieves. Collins later said, “Candy taught me more about sensuality than I had learned in all my years.”

The West Coast jobs put her in touch, literally, with a circle of famous patrons who were attracted to Candy in the way pack rats are drawn to glitter. Gary Crosby, Bing’s son, is said to have remarked, “One thing about that broad: She can make you feel like a real man.”

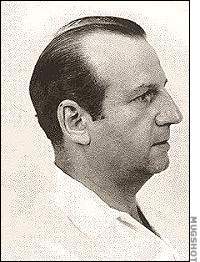

Barr became a squeeze of Mickey Cohen, the L.A. mob kingpin, whom she met while headlining at the Largo Club on Sunset Boulevard. (He was a sucker for strippers; Tempest Storm and Beverly Hills had been in his bed, too.)

In one of the more curious news bulletins of that era, scores of newspapers ran stories when the gangster and his moll announced they were splitting up.

“It’s just one of those things,” said Cohen. Added Candy, “He’s a nice guy, but we just weren’t meant for each other.”

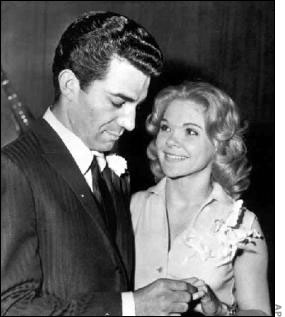

Instead, Candy settled into an equally peculiar pairing. She married Hollywood hairdresser Jack Sahakian, the Vidal Sassoon of his day, in Las Vegas in 1959.

They didn’t have much of a honeymoon.

The West Coast romancing was a distraction from a very real problem that Candy was having back in Dallas.

Texas politicians were in high dudgeon over the narcotics menace in the late 1950s, and cops made a habit of pulling penny-ante drug raids on targeted citizens.

Candy Barr, the stripper who danced her way around the assault rap for shooting her estranged husband, was a likely target for bluenoses on the vice and morals squad.

In October 1957, Dallas police Detectives Bill Frazier and J.M. Souter knocked at her apartment door. They told her an informant had tipped them that she had marijuana.

After a brief give-and-take with the cops, Candy dug down into her bosom and pulled out a pill bottle that contained less than an ounce of pot, the equivalent of the tobacco in 25 cigarettes.

Candy was certain she had been framed by police. She said a girlfriend had dropped off the pot for safekeeping the day before.

She believed that police caught wind of the marijuana babysitting job by a wiretap on her phone. Through her own detective work, she learned that an undercover cop using a false name had rented a flat across the hall from her.

In those days before strict legal protocols, cops used wiretaps without restraint. Candy’s lawyers could never get police to admit to the wiretap, even after the phone company said it was true. Nor would they reveal the name of the alleged informant.

The trial of Candy Barr was a spectacle, with men elbowing their way into the courtroom to ogle the stripper.

The Morning News reported one day, “The courtroom was again crowded with spectators, 75 percent of them men.”

Under Texas’ draconian “Reefer Madness” laws, Candy faced up to life in prison for the handful of marijuana. She did not testify in the weeklong trial. The jury of 11 men and one woman deliberated nearly three hours before returning a guilty verdict.

Prosecutor James Allen argued for a 25-year sentence. She got off easy. The jury sent her away for just 15 years.

Candy’s head fell toward the defense table when she heard the verdict.

She stood and tried to read a protest statement to the jurors, but she lapsed into tears when the judge tried to cut her off.

Later, she told reporters, “It was an unfair verdict, but my spirit is not broken. At least we showed what the police department is doing.”

She added that jurors “made up their minds before the trial started.”

Some years later, a Dallas police official opined that Candy had been convicted because of her occupation. He said the 11 men on the jury would have been mortified to go home to face their wives after acquitting her.

Candy almost certainly would have been acquitted under search and seizure laws established in the 1960s.

But she lost in appeals all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court — a legal effort funded in part by Mickey Cohen. In January 1960, weeks after her wedding with Sahakian, her appeals ran out, and she surrendered to Goree Prison Farm for Women, near Huntsville.

Although she resented being there, Candy used her prison times wisely.

She earned good-time credit by working earnestly in the prison laundry and by attending classes to catch up on some of the high schooling she had missed out on.

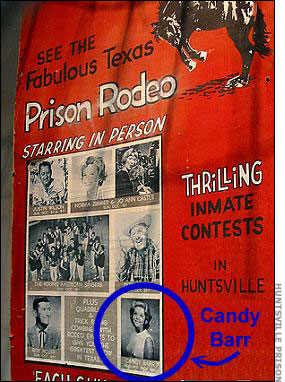

And she managed to keep her hand in entertaining while behind bars. She was a star attraction at the famous annual rodeo at the Huntsville state prison — as a singer, not a stripper.

On April 2, 1963 — after three years and three months — she walked out of prison carrying a Bible and holding a $5.70 one-way bus ticket back home to Edna. As a condition of her parole, she was barred from working as an exotic dancer.

“I’m through being a stripper,” she said. “Prison gave me the opportunity to realize I wasn’t bad. I don’t think there is any way to describe what I was when I walked into prison. But I walked out a human being.”

Candy said she wanted to get home to Edna, forget her silly stage name and go back to being Juanita, a simple Texas housewife.

But she could not escape the spotlight.

Jack Ruby, her old Commerce Street nightclub pal, visited Barr after her release and gave her a getting-out gift of two dachshund puppies.

The dogs were about six months old when Ruby’s name popped up on every newspaper front page in America.

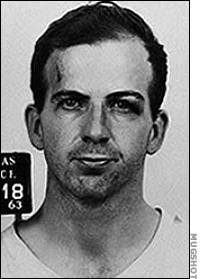

Lee Harvey Oswald, an alienated man obsessed with Russia and Fidel Castro, shot President Kennedy to death in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963. Two days later, Ruby shot and killed Oswald.

Just 12 hours after that second shooting, the FBI paid a visit to Candy Barr to see what she knew about the assassination of President Kennedy and the murder of his killer.

She said she knew nothing, but to this day some view Candy as a cog in the arcane machinery of the Kennedy conspiracy.

When this latest kafuffle in her life began to ebb, Candy apparently re-evaluated the career reassessment she had done while imprisoned.

Hairdresser Sahakian divorced Candy when she was sent away, and in March 1964 she took her fourth husband, James Wilson, a humble railroad worker from Louise, Texas.

In 1965, she sought to lift the parole restrictions that prevented her from resuming her career. She was denied but she persisted. In 1969, as her 35th birthday approached, Candy applied for reinstatement to the American Guild of Variety Artists.

But her life was again detoured by a police marijuana raid. This time, she was living in Brownwood, Texas, caring for her dying father, when police arrived on March 11, 1969. The case was eventually tossed because the seizure of the miniscule amount of pot was ruled illegal

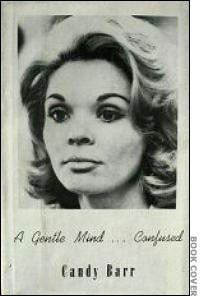

In 1972, she published a slim volume of poetry, “A Gentle Mind… Confused,” some of which she had written in prison.

The title poem reads:

“Hate the world that strikes you down,

A warped lesson quickly learned,

Rebellion, a universal sound,

Nobody cares … No one’s concerned.

Fatigued by unyielding strife

Self-pity consoles the abused,

And the bludgeoning of daily life

Leaves a gentle mind … confused.”`

The third act of Candy’s life, as an aging sex symbol, was filled with those sorts of confusing contradictions.

In every interview she gave, she decried her notoriety as Candy Barr and the occupation that made her famous. Yet she returned to that name and that career when it suited her financially.

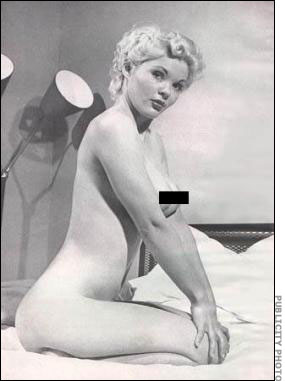

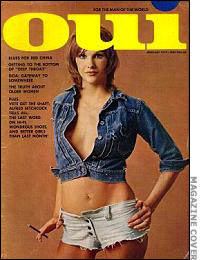

She was lured out of retirement from the skin trade by a $5,000 payday when she posed nude for Oui magazine in 1976, at age 41.

During the ’80s, she made occasional appearances at strip clubs in Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Dallas. She danced her final burlesque gig in 1998, at age 62, at the Ruby Room in Dallas.

By then, she had gone from a sex outlaw to a novel and revered Lone Star original — like a real-life Larry McMurtry character.

In 1999, she was named to Playboy’s “Most Desirable” list, and she made Texas Monthly’s list of “perfect Texans.”

“Of all the small-town bad girls,” the magazine said, Candy Barr “was the baddest.”

But she had long since grown weary of the attention.

”Let the world find someone else to talk about,” she told the Texas magazine.

Candy Barr, 70, died of pneumonia on Dec. 30, 2005, at a hospital in Victoria, Texas, not far from her hometown.

She had moved back to Edna in 1992. She lived quietly in a modest house. Neighbors said she kept to herself and went out only when she had to — for groceries and whatnot.

No one who crossed her path would have guessed that she was a sex icon and an inductee of the World Burlesque Museum.

Yet, the demure retiree had legions of admirers among sex workers. They have created a tribute page to her on MySpace.com, and copies of her book of poetry sell for as much as $3,000.

Many view her as an archetypal brassy, sassy and self-assured woman who used her sexuality on her own terms, in an era when females were expected to be sexually subservient.

That makes her a seminal figure in “the history of sex work,” said Annie Sprinkle, the former stripper and porn star.

“It’s important to remember and honor our predecessors, to know our erotic heritage,” Sprinkle told the Crime Library. “Candy was certainly an influence on what would become the ‘sex positive’ feminist movement, and strippers today emulate her.”

It’s not clear that Candy accepted the sex goddess mantle without some regret.

She was proud of her career as an exotic dancer. But as she aged, she often lamented her one appearance in a stag film.

During various interviews, she claimed that she was either drugged or forced at gunpoint to do the sex scenes for Smart Alec. Skeptics note that she appeared lucid and engaged in the film.

In any case, her age at the time of filming makes her a victim.

100 Years of Sex in Film

One stag film expert told the Crime Library that her 20 minutes as a porn star became a lifelong burden for her.

“It ruined her life,” said Luke Ford, author of A History of X: 100 Years of Sex in Film. “She regretted it all her days.”

Some exotic dancers revel in the power they feel onstage — their control over the men in the audience, and over their libidos.

But in one of her last interviews, Candy Barr said she was never particularly interested in that dynamic of exotic entertainment.

She wasn’t trying to turn men on, she said. She simply wanted to dance.

Interviews with Annie Sprinkle, Luke Ford, Kate Bornstein, et al

Historical archives of the Dallas Morning News

A History of X: 100 Years of Sex in Film, Luke Ford, Prometheus Books, 1999

Dirty Movies: An Illustrated History of the Stag Film, 1915-1970, Al Di Lauro and Gerald Rabkin, Chelsea House, 1970