All about Female Offenders, by Katherine Ramsland — Bad Girls — Crime Library

While criminologists insist that female offenders represent only a fraction of the crime perpetrated in our society, the numbers of female criminals appear to be growing. Some act out in male-female teams while many initiate crimes on their own. Female killers get more press than offenders in other types of crimes, yet the less violent behaviors still do reveal a lot about women who break the law.

In Good Girls Gone Bad, journalist Susan Nadler talked with a variety of women in prison and found that they tended to fit into one of several categories:

- Acting out or defying an image: People think of you in a certain way and you want to do something outrageous to prove that you’re not what they think.

- Snapping: While this is a controversial diagnosis, in ordinary language it means that someone was pushed by events to the breaking point.

- Being the outlaw: they pursue crime to develop an image that they perceive as cool or working outside social boundaries. (One woman with whom Nadler talked had grown up privileged, but by the time she was 24, “Rosa” had pulled over 500 burglaries, had three men working for her, and was earning over $200,000 a year.)

- Addiction: 90% of women in prison have substance abuse problems.

- Following a role model: Especially in gangs, girls who see those they respect committing a crime tend to do the same.

- Keeping someone’s attention or affection: Many women who team up with men get involved in their criminal activities as a way to keep them romantically involved. They end up in prison for crimes they might not otherwise have done.

- Obsession: Some women develop a fixation that involves crossing legal boundaries.

- Justification by the act of others: they did it and so can I.

What Nadler does not mention is that many women end up in prison because they’ve retaliated against abuse as a way to protect themselves and their children. The majority of violent crimes committed by women fall into this category. Some women are also duped by boyfriends or spouses to become part of an illegal operation, and they unwittingly participate and get arrested. As a Court TV movie Guilt by Association illustrated, sometimes a woman has only to pick up the phone or carry a package, and she’ll get a heftier prison sentence than the maneven than many murderers.

Behind Bars

Wensley Clarkson interviewed many women in maximum security prison, as documented in Women Behind Bars, and found females who had kicked someone to death, slaughtered family members, based a business on drugs, and hired hit men to kill someone. “Female crime is now increasing at an alarming rate,” he says, “fueled by a drastic increase in drug use and the cold hard fact that many women are now having to fend for themselvesand some of them, just like their male counterparts, cannot cope.”

Girl Out

Yet there’s been little research on the nature of female aggression. In Odd Girl Out, Rachel Simmons, a trainer for the Ophelia Project, tries to raise the self-esteem of girls, discusses female bullies and the fact that little has been written about what she calls the hidden aggression prevalent in the culture of girls. She went to several grade schools and sent out requests for stories from other women about experiences in their lives with female bullies, and she was amazed at the response. While society at large supports the myth that females are “civilized” and nice, in fact, there are some who simply want to gain power and control over others, and even to harm them. They do it in subtle ways, such as a hurtful glance, passing nasty notes, ganging up, and using innuendo to ruin another girl’s reputation. “If girls are whispering,” says one, “the teacher thinks it’s going to be all right because they’re not hitting people.”

Such teachers contribute by accepting social stereotypes. The damage these girls do in quieter ways can be just as devastating as a bruise or broken bone and can have residual effects throughout the sufferer’s lifetime. It isn’t necessarily an outsider with a chip on her shoulder who does this, either; it might be the queen bees in some clique who plan to make the life of a target girl miserable.

“The adults pass through the same rooms and live the same moments,” Simmons writes, “yet they are unable to see a whole world of action around them. So, too, in a classroom of covertly aggressing girls, victims are desperately alone even though a teacher is just steps away.” And sometimes those victims want to hurt someone back.

It’s no wonder then, that given the opportunity, some women will freely do things that harm others. In a culture that protects female bullies and psychopaths through denial and superficial stereotypes, aggression can seep in through many forms.

While many women get involved with men in prison, they tend to believe that their love will redeem the man’s crime. However, some offenders exploit that notion and rather than being affected positively by their newfound friend, they exert a strong negative affect on the woman.

(CORBIS)

Kenneth Bianchi pleaded guilty to the murder of two college coeds in Bellingham, Washington, and to five of the 10 murders in Los Angeles in 1977 and 1978 attributed to “the Hillside Strangler. He attempted and failed at malingering, a multiple personality disorder, so he agreed to testify against his cousin, Angelo Buono. However, he was playing games with the Los Angeles investigators, pretending to have memory lapses.

Then in June 1980, a 23-year-old playwright and actress, Veronica Lynn Compton, contacted Bianci in prison, according to Court TV’s Mugshots documentary, “The Hillside Strangler.” She told him that she identified with him. They got together and came up with a plot to save him: She would go around the country and kill women as a way to show that the Hillside Strangler was still at work. They had imprisoned the wrong man. He had given her some body fluids for her to use to make it look like a rape and murder.

clopedia of Serial

Killers

In his Encyclopedia of Serial Killers, Michael Newton describes how she went first to Bellingham to lure a woman to her death. She checked in to the Shangri-la Motel and then spotted a short woman who worked in a bar. She thought it would be an easy task to dispatch with her, so she brought the woman to the motel and tried to strangle her. Veronica was a woman without much muscle, while the intended victim was athletic and worked another job with the Parks and Recreation Service. She struggled and got away, while Veronica was arrested.

police file photo

She was tried for attempted murder. Her one “acting job” had backfired and she was convicted. Her hope to get Bianchi out of prison and unite with him had separated them both rather permanently. She testified at the trial of his partner Angelo Buono, admitting to the plan to do all of this and then frame him.

While her idea was to mimic the crime of a man, she clearly did not create the scenario on her own, and might never have instigated such a behavior had she not met Bianchi. Psychopaths can have that affect. However, some women appear to be psychopathic in their own right.

(AP)

In the movie To Die For, Nicole Kidman starred as a weather girl who seduces a high school loser into killing her husband with the false belief that they can then be together. Helen Hunt portrays the true-life person, Pamela Smart, in a made for TV movie.

Twenty-year-old Pamela Smart, blondish and pretty, was on staff at the Winnacunnet High School in Hampton, New Hampshire. She taught media studies and offered a course in self-esteem. Bill Flynn, 15, was immediately infatuated.. One day she asked him to come to her office after school. He was excited at the prospect, because he had his fantasies, but he also knew that she was married.

According to true crime writer Wensley Clarkson, Smart handed young Bill an envelope full of photographs of her in skimpy underwear and said, “I hope you like them.”

pose (AP)

As he nervously looked through them, she sang a song, “Hot for Teacher.” She teased him and promised more another time. It wasn’t long before she invited him to her home. Clarkson claims that her motive was to gain a lover during the many nights when her salesman husband, Greg, was not at home. She’d discovered he’d been unfaithful and she had many regrets about marrying him. She hoped for someone who would pay her more attention.

When Bill arrived, Pamela had him watch the erotic film, 9 and 1/2 Weeks with her. She had a 16-year-old girlfriend there who was meant to be a cover in case anyone had seen him arrive. Then she left and Pamela proceeded to get Bill worked up.

As she drew him in, he later said that she had hinted about them having a life together, and had suggested that her husband was in the way. It seemed that the plan was to get Bill so infatuated that he would do anything for her that she asked. At any rate, that’s how he interpreted it, and when she insisted that he had to kill Greg, he got two of his friends involved. With the promise of $4,000 a piece, they got ready to do it.

The first attempt was aborted when Bill got cold feet, but then he and his friends entered the Smart home one evening and shot Greg Smart in the back of the head.

Pamela dressed in black and cried at his funeral.

She then told the boys to stay away from her and failed to give them any money. Even Bill was cut off.

Eventually one of the boys broke down and confessed to his parents. They went to the police, who persuaded Pamela’s girlfriend to wear a wire and get the woman to say something incriminating. Apparently she did admit to her part, including an innuendo that she’d set up the boys to take the fall.

In 1991, Pamela Smart was convicted of masterminding her husband’s murder and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Despite the fact that all four students testified against her, she claims she got an unfair trial and that she and her mother are working hard to prove that.

Another woman who claimed to be innocent of her crime took a different route: she said she was brainwashed.

Patricia Hearst was the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst, the wealthy newspaper magnate. Her story is described in “The Perils of Patricia,” in The Saturday Evening Post in 1976, and in her autobiography, Every Secret Thing.

SLA (CORBIS)

In February 1974, she disappeared, supposedly the victim of a kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA). Then in April, she showed up as part of a bank robbery team, holding a carbine rifle while the others robbed the Hibernia Bank in San Francisco of more than $10,000. Two people were wounded as the robbers fled. Hearst released several tapes that indicated some allegiance with these people, who were supposedly fighting a revolution on behalf of the underprivileged. On the tapes, she called her family “pigs.” She was now “Tania.”

In 1976, after a year and a half on the run, she was caught by the FBI and put on trial. F. Lee Bailey was her defense lawyer and he was quite confident he could get her off. There was much discussion about whether or not she had been brainwashed into her involvement and a great deal of speculation that she had simply fallen in love with one of her captors. In the end, the jury didn’t buy the idea of mind control, and Hearst was convicted of bank robbery. She served less than two years in prison before President Jimmy Carter commuted her seven-year sentence in 1979. President Clinton eventually pardoned her.

Soliah (AP)

Another member of that gang, Kathleen Ann Soliah, helped to plant two pipe bombs in a police car, meant to kill as retaliation for a shoot-out with the SLA that had resulted in the deaths of their core group. Soliah disappeared in 1976, going underground and reappearing in a St. Paul, Minnesota suburb as Sara Jane Olsen, married with kids. According to Thomas Carney in Los Angeles Magazine, she fed the homeless, read to the blind, and taught English as a second language. She now lived in a degree of affluence that she had once despised and even advocated gun control.

She was caught in 1999 and sent to Los Angeles to face charges of conspiracy to commit murder. In Hearst’s book, she says that Soliah had also taken part in a bank robbery in which a customer was shot and killed.

Females can be aggressive, ready to use the weapons of choice more typical of males, but sometimes their aggression is made through romantic gestures that they believe justifies what they do to others.

In 1992, Mary Kay LeTourneau noticed a boy in second grade at the elementary school where she taught who seemed to have real artistic promise. He was part Samoan, so Vili Fualaau’s dark features were exotic in the Seattle, Washington area.

Over the next four years, she kept her eye on him and when he graduated from her sixth-grade class with high marks, she took him out to a restaurant. There, he said in a deposition interview aired on Court TV’s documentary Forbidden Desire, she started to play “footsie” with him. After the meal, they talked together in Mary Kay’s car and he said he wanted to kiss her. Within a few days, they were making love on the roof of her house. She was 35; he was 12 and a virgin.

LeTourneau (AP)

They continued their secret affair, convinced they were soul-mates, but then Mary Kay realized she was pregnant. Already married for eleven years with four children, she now had to face the music. Her husband Steve found letters from Vili and he confronted the boy, who admitted to the liaison. Steve told him to stay away.

Then a distant relative called the school and it wasn’t long before Mary Kay was arrested on a charge of child rape. She insisted it was love, but love isn’t considered in the law that says adults may not have sexual contact with children. Consent by the child is irrelevant. Generally child abusers are male, yet this one was not only female but also a schoolteacher. It was a unique case that stunned the nation…although it would not be the last such illicit affair between an older woman and an underage boy.

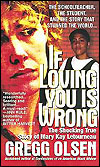

You Is Wrong

It then came out, according to Gregg Olsen, author of a book on the case, {If Loving You Is Wrong}, that Mary Kay was the daughter of a once-famous California congressman who had disgraced himself. John Schmitz, a prominent member of the John Birch Society and profoundly right-wing, was riding high on his success when it turned out that he’d had two illegitimate children with one of his campaign workersalso a former student. His double life ended his career.

Many people adopted the theory that this was Mary Kay’s psychological legacy: she was doing exactly as her father had done. However, that’s not only simplistic but fails to allow Mary Kay to be aware of her own actions.

While waiting for trial, Mary Kay had a daughter with Vili. Then on August 7, 1997, she tearfully pleaded guilty to two counts of child rape. While the prosecutor insisted that this was a serious crime, Judge Lau appeared to believe in Mary Kay’s sincere interest in getting help. However, several journalists noted from a tape of the proceeding that as she took her seat after making her plea, she smiled at her lawyer in a way that hinted at self-satisfaction. Judge Lau sentenced her to 89 months in prison and then suspended the sentence in lieu of her taking medication, attending a sex offenders’ treatment group, and having no contact with the boy. Mary Kay had to serve five months of her sentence, but was then free to go back to her family.

Her courtroom insincerity quickly played out when upon her release from prison she contacted Vili and continued to see him, having sex with him in her car. During one episode, a police officer came upon them and she was once again arrested. Found inside the car was her passport, new clothing, and over six thousand dollarsa good indication that she meant to flee with Vili and their child. She was also pregnant again. This time, the tears she shed in court made no impression as the judge reinstated the sentence and sent her to prison for seven years.

Steve divorced her and took the children to Alaska.

In prison, Mary Kay had her second daughter, which was given with Vili’s other child to Vili’s mother to raise.

In June 2001, Vili said that he might want to spend the rest of his life with Mary Kay, but he was fidgety and evasive. He’d just turned 18 and probably realized he had his whole life ahead, while Mary Kay was now in her 40s.

Mary Kay has both supporters and opponents and the debate rages on as to whether a male adult abusing an underage female is a serious matter while a female with an underage male is not. And should love have anything to do with what happens to the offender?

But then, one might also wonder about the nature of an obsessive love that exploits immaturity and vulnerability, not to mention a position of trust. Mary Kay appears to have been meeting her own needs, in particular upon violating the court’s order as soon as she possibly could. Vili himself admits that mistakes were made and that the situation probably should not have been allowed to get out of control. While he and Mary Kay have written a book on the subject, published in France, his demeanor during interviews is less than enthused.

There is also a theory that Mary Kay suffers from a mental disorder and thus had no control over her actions. Psychiatrist Julie Moore examined Mary Kay for the defense and diagnosed her as having bipolar disorder. In other words, she showed periods of intense energy and activityincluding hyper sexualitycoupled with short periods of depression. That can induce inappropriate behaviors, impulsivity, and impaired judgment. She might find reward in high-risk behavior and remain unaware of the consequences.

A psychologist who treats sex offenders, Susan Moores, was quoted in an article about Mary Kay’s disorder as saying that Mary Kay shows a deviant sexual arousal pattern. Moores resisted the notion that bipolar disorder was to blame. The cause, she insisted, was the decision that the offender made.

Nevertheless, her behavior was different when on medication than when off, and she admitted to stopping her medication once she was out of prison. She does not accept that she’s bipolar and she continues to insist that she and Vili are in love and will spend the rest of their lives together. Since she’ll remain in prison until 2004, it remains to be seen how long a teenage boy will wait for her.

She’s not the only one to have seduced a boy in her charge. There have been several reports in recent years about teacher-pupil sexual abuse.

According to Court TV, Beth Friedman, 42, was convicted in Florida of contributing to the delinquency of a minor, Donald Vaden, because the boy claimed that when he was only 15, she offered him gifts of alcohol and drugs in exchange for sex. Her defense was that he was extorting her for money by making up lies. In the same state, Denise McBryde, 38, admitted to having sexual relations with a 15-year-old student, while in Minnesota, Julie Feil, 32, pleaded guilty to a three-month sexual affair with a student, claiming that she loved him “the best way I knew how.” Kimberly Merson, 24, brought eight underage boys to her home, got them drunk, removed their clothes, and had sex with them.

These women initiated the activity, taking advantage of boys who were sexually stimulated and flavoring their crime with a romantic tone. There was no violence involved, some of them say, and the boys were willing, so what is the problem?

They’re abusing their roles to satisfy themselves. Romantic or not, they are female sexual offenders.

Such women represent about 10 percent of all sexual offenses, and their abuse often involves their own child or children. Some have only one victim, many have several. Psychologist A. J. Cooper cites a study that 20 percent of these sex offenders even resort to force. He points out that the reasons why some women become recalcitrant sex offenders is incompletely understood, but he feels that it may result from a combination of hyper sexuality, associations with early sexual experiences, and imitation of abuse perpetrated on them. They even tend to use the same forms of abuse that they had once experienced. Most of them are immature, dependent, and sensitive to rejection, so they tend to gravitate toward younger people who are not their peers. The risk of rejection is less likely and they create situations in which they can be in control.

Psychiatrist Janet Warren and psychologist Julia Hislop also researched female sexual offenders, and in Practical Aspects of Rape Investigation, they offered a typology:

- Facilitators women who intentionally aid men in gaining access to children for sexual purposes

- Reluctant partners women in long term relationships who go along with sexual exploitation of a minor out of fear of being abandoned

- Initiating partner women who want to sexually offend against a child and who may do it themselves or get a man or another woman to do it while they watch

- Seducers and lovers women who direct their sexual interest against adolescents and develop an intense attachment

- Pedophiles women who desire an exclusive and sustain sexual relationship with a child ( a very rare occurrence)

- Psychotic women who suffer from a mental illness and who have inappropriate sexual contact with children as a result

In some cases, women who lacked ongoing relationships with men put their male children in the role of substitute lover, and there are cases in which the sexual contact is used as revenge against a male partner. These female perpetrators generally come from chaotic homes. “Not only does this have long term effects on the children,” these researchers note, “but it also serves as a contagion that follows victims into the next generation with repetitious and cyclical traumatization of others.”

Some of these women get involved with men who then use them in more serious crimes, although the majority of partners in murder appear not to have suffered abuse. How they get to the point of criminal behavior is more often influenced by how the partner treats them over a period of time.

Former FBI Special Agent Robert Hazelwood, Dr. Park Dietz, and Dr. Janet Warren conducted a six-year study together on 20 women who had been the wives and girlfriends of sexual sadists, “the most cruel, intelligent, and in some cases, criminally sophisticated offenders confronting criminal investigators today.” They relied on a protocol of 450 questions and published the results in the third edition of Practical Aspects of Rape Investigation. Thirteen of the women had married their partner and the remaining seven had dated the man exclusively. Most of them had been persuaded to engage in a variety of deviant practices, such as sex with animals, sex in groups, bondage, and being whipped. Seven of the men had killed numerous victims, and four of the women were present for those murders. Eventually they all feared for their lives or the lives of their children.

Hazelwood thought it was more revealing than talking with the offenders themselves. “With offenders, you get lies, projection, denial, minimization, or exaggeration. The wives and girlfriends are just like a sponge. They ask, “How can I help? What do you need to know?”

He understands that they may be lying as well, “But at the same time, you’ll get insights into the offender that you’ll never get from the offender himself. For example, what type of fantasy would he act out? They would tell this in detail.”

The surprising thing to him was how normal the women seemed. They had come from middleclass backgrounds and usually had no criminal record. They weren’t abused or mentally ill. The thesis of the study is that the males target vulnerable women with low self-esteem and then go to work on them, gradually making them compliant and willing to do almost anything.

“The behavior gets reinforced with attention and affection, gifts, and excitement,” Hazelwood points out. “Eventually they’re doing things that isolate them and further lower their self-esteem. All they have is this guy, so they cooperate.”

The interviews lasted from five to 15 hours. Five of the women had been involved in outright homicides. The interviewers asked about the women’s personal history, the men’s history, their courtship, and their life together.

“One of the women that I talked to was involved with her husband in the murder of more than five people. This woman was a very intelligent and attractive person. Prior to meeting her husband, she was successful. When she met him and she told me that she perceived a dark side to him that was kind of attractive. She’d led a rather sheltered life. When they dated, he was always a perfect gentleman. He brought gifts and he was older by several years.”

“He was everything she wanted a man to be. He was a considerate and sharing lover, spontaneous, exciting to be around, complimentary, good-looking. Then after they got married, he began to beat her, primarily on the sexual parts of her body. He used vulgar terms for various parts of her body and for his sexual organs. He had sadistic fantasies involving degradationverbally, sexually, and physicallywhich he acted out on her. Eventually he convinced her that he wanted a sex slave, so they kidnapped one and he killed the victim. According to this woman, that was a surprise. She didn’t anticipate that, but now she’s an accessory to homicide. They continued with this and ended up with more than five victims.”

Hazelwood and Burgess identified a specific five-step process that all of the offenders seemed to follow to transform their partners into active or passive accomplices:

- Identification: They know whom to target

- Seduction: They use all the normal techniques

- Reshape the target person’s sexual norms

- Social isolation

- Punishment

The women end up going along with what the men want, because the men have used psychological battery to change how they think and behave. Then when they get caught and tried for their part in the crimes, they have a difficult time accepting that they did these things.

Some of them use that opportunity to turn their lives around, and in some prisons, programs are offered with the hope of influencing women who once committed a crime to re-evaluate how they got to prison and make sure they don’t go back. One such program is thriving in the maximum-security unit of a women’s prison in New Jersey. Let’s hear from some of the women who have learned something from linking their lives to literature.

Institute

Edna Mahan, one of the first female correctional superintendents in the country, experimented with innovative approaches to rehabilitation. In 1928, when she started her work, Clinton Farms was the New Jersey reformatory for women outside Clinton. Mahan stayed there for forty years. It is now known as the Edna Mahan Correctional Institute for Women, under Superintendent Charlotte Blackwell and her assistant Bill Hauck, and it houses around 1,200 female inmates.

There are over 90,000 women in prison today, and 90 percent of them are mothers. According to the statistics on prisonactivist.org, the typical profile of the female inmate is that of a young, single mother without much education or many marketable skills. More than three-fourths of these women are between the ages of 25 and 34, and many have experienced sexual or physical abuse. Typical convictions are for property crimes or for defending themselves against abuse, and men tend to serve less time for the same crimes as women. Men also get to spend more time on average outside their cells. Contrary to common notions, 80 percent of incarcerated women are nonviolent.

In the spring of 2001, English professor Michele Tarter from The College of New Jersey in Ewing, volunteered to start a 10-week literature class there in the maximum security unit as a way to give incarcerated women their voicesand some hope. “I felt a very strong leading to do this,” she said, and she calls it WOMAN is the Word! Using the stories of powerful women who have endured and transcended hardships such as slavery, captivity, rape, and disability, Dr. Tarter urges her students, 14 at a time, to think about those stories and express whatever impact they feel on their own lives. That way they improve their skills, but they’re also encouraged to contemplate their own situations.

Tarter, a scholar in Early American literature and women’s studies, had once devised a similar program in a correctional facility in Illinois, and she’s quite amazed by the creativity and vision she finds among those who are locked away. “When I walked into a prison for the very first time,” she recalled, “I felt a surge of light and energy.”

Inspired by books like The Handmaid’s Tale and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, the women discuss the stories in an intimate circle and then write poetry, fiction, and short autobiographical accounts of their feelings and their growing self-awareness. These they read to one another, and Tarter then collects them into a booklet for the women to keep. Among their assignments are exercises from Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones, in which they may write for 15 minutes about a frightening incident or about a special place. Reading Audre Lorde, an activist and author who died of cancer, they learn about the importance of finding a voice. “My silences have not protected me,” Lorde writes. “Your silences will not protect you.” She urges them to be warriors, and they hear the message.

The educational director’s assistant, Cathy Morgan, provided observation in the prison one afternoon as five “graduates” agreed to talk about how important the program was to them. Because they have discovered the joy of reading and personal expression, they now hope they can inspire others to start similar such programs in other places. Maria Szivos, Robin Easterling, Delitha Hull, Margaret Deluca, and Tina Dixon-Spence were quite vocal about why such programs are beneficial for women behind bars.

“It made us feel like women again,” said Margaret, who wrote about the importance of expression in the prison newsletter. She liked the character of Sara from Anzia Yezierska’s Bread Givers, because through another woman’s experience with a controlling father, Margaret sorted through issues with her own father. “I did everything wrong in his eyes,” she explained. Yet she found the courage to write him a letter. She’s 53 and looking forward to getting out within a month. In fact, reading and writing gave her both the self-esteem and the cognitive tools needed to craft a plea for parole to the judge when her lawyers did little but suck up her money. “I represented myself and told my story,” she said with pride. The judge was impressed with her articulate account, and accomplishing what her lawyers could not, she beat the odds that said she would remain in prison for many more years.

“It validates me,” Tina insisted about the program. She was quite passionate about continuing to learn. “I know that there’s no human pain that another woman has not endured and it connects me. I find out things about myself that I wouldn’t otherwise have realized.” She has postgraduate training and knows how important it is to learn the right way of thinking to avoid being among those who recidivate. She’d rather be on the outside working as an advocate for better conditions. Gesturing toward her tan prison uniform, she said she was tired of feeling like an overgrown peanut with a number and no identity. Recently, she had made integrity a central issue in her life, and reading about other women with similar struggles helped her. “I’ve had to find value in being here, and through this group I’ve learned that integrity is about responsibility. It’s ironic that I feel the best about myself in prison, because I’ve learned that values come from within.”

Robin, alert to the needs of others, likes Celie in The Color Purple. “I can put myself in her place and see that, oh my God, I’m going through that. This is what she did, so this is what I have to do. I learn from these books. It’s changed my life. I hold my head up high now.” She wants to help women in prison who can’t read, and she has encouraged one friend to learn to read better so she can tell the stories to her partner. All of them liked the idea of “paying it forward,” taking what Dr. Tarter has brought to them in prison and giving that joy and sense of hope to others.

Delitha, trained to be a literacy teacher and paraprofessional, mostly listened to the others, but when she spoke, her opinions were strong and clear. She watches girls in the yard, and when they come into the classroom and learn some skills, it makes a significant difference in how they behave. “They become a different person. They want to learn.”

The program is not just about reading and writing; it’s also about sharing and creating connections. “You read a book in this group and you hear ten points of view on it,” Tina explained. “You find you share a link and now you have something among you that grows and grows.” In fact, all of the women spoke excitedly about how they’ve shared the books from the program with other inmates, encouraging them to experience the same joy of reading that they have. “Every time one person returns my books,” said Robin, “someone else asks, can I read that next?” Some of them want to become mentors to the juvenile girls that come in, to provide them with better role models.

They all know how hard life can be, and being in prison is harder still. “Sometimes our strength just collapses,” Robin admitted, “but these books help us keep going. We know we’re not alone.”

In fact, for a long time, they had only a few books to read there, but that situation has changed. When Tarter learned that the women in “max” had a limited library, she organized a book drive. “They were pleading with me to get books,” she recalled. In only a month, the students at her college collected more than 3,000 donations, and Tarter hauled them all to the prison. “I did it to keep the fire going.”

Maria, who works with inmates who have severe mental or emotional problems, talked with careful deliberation about the lack of funding for educational programs in state prisons and about the fact that college credits are available only to women under 25. She would like to work to change this policy”you need positive structure in your life”but in the meantime, she hopes that more people like Dr. Tarter may think about volunteering. “She gave us a program that allowed us to open up and associate our voice with our feelings,” she explained, going on to say that without a voice, women fall into a lethargic state and their problems are then multiplied. “We need people who believe in us to help us with skills that will build our self-esteem.”

It’s clear from the animated discussion that, thanks to reading and writing in this manner, these women have found a new sense of self and a more positive direction. “I didn’t think I’d take something good from being in here,” said Margaret as the meeting came to a close, ‘but I have.”

They like the feeling that they’ve become “wise women,” as Tarter referred to them each week, and they hope to pass that on to others. Edna Mahan would be pleased.

For those interested in starting such a program elsewhere, Dr. Michele Tarter can be reached at tarter@tcnj.edu.

Bean, Matt. “If Convicted, Friedman Not Alone Among Teachers,” Court TV Online, December 11, 2001.

Clarkson, Wesley. Women Behind Bars. NY: St. Martin’s, 1998.

Cooper. A.J. “Female Serial Offenders,” in Louis B. Schlesinger, ed., Serial Offenders: Current Thought, Recent Findings. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2000.

Edwards, Tamala. “Mad About the Boy,” Time.com. Feb 16, 1998.

“The Hillside Stranger,” CourtTV Mugshots.

“Forbidden Desire,” CourtTV Mugshots, Sept 2001.

Chat with Gregg Olsen, CourtTV.

“Florida Teacher Sentenced to Probation, Counseling,” CourtTV Online, Jan. 18, 2002.

Gregg Olsen. If Loving You is Wrong.

Hazelwood, Robert R. and Ann W. Burgess. Practical Aspects of Rape Investigation. 3rd Edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2001

Interviews at Edna Mahan Correction Facility for Women in Clinton, New Jersey.

Nadler, Susan. Good Girls Gone Bad, New York: Freundlich Books, 1987.

Newton, Michael. The Encyclopedia Of Serial Killers, NY: Checkmark Books, 200.

Purse, Marcia. “CriminalOr Victim of BP?” bipolar.about.com

The Mary Kay Letourneau Story: All American Girl USA Network, January 18, 2000.

Simmons, Rachel. Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls. NY: Harcourt, 2002.