All about Evil acts and people by Katherine Ramsland — I Need You to Be Dead — Crime Library

EVIL, PART TWO: THE HEART OF DARKNESS – REFRAMING EVIL

I Need You to Be Dead

Jeffrey Dahmer and Dennis Nilsen were both ordinary people who became quiet killers, merging their sexual excitement over corpses with an intense loneliness that they wanted to alleviate. Exploiting others for their own needs, to the extent that the others had to die, made these men evil.

Former army veteran Dennis Nilsen lived in London and picked up his victims in pubs. As Brian Masters, author of the definitive biography of Nilsen put it, he was “killing for company.” His first murder occurred near the end of 1978, which sexually excited him. He strangled the man with a necktie and then placed him beneath the floorboards of his apartment until he could cremate the remains in his garden. He continued to acquire companions in this way, strangling them, bathing the corpses, sometimes taking them to bed, and finally butchering them or storing them in various places in his apartment. Often he flushed parts down the toilet, which eventually proved to be his undoing. When the septic system clogged in the building, an investigation led to Nilsen and he pointed out a closet where police found the dismembered parts of two different men, the head of one with the flesh boiled off. Another torso was found in his tea chest, and he was arrested. He then confessed to killing 15 men over the past five years, partly because the idea of them leaving his apartment made him feel too alone and partly because he simply enjoyed it.

(CORBIS)

Similarly, Jeffrey Dahmer in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, came to the public’s attention in July of 1991. He managed to murder 17 men before one potential victim ran away, handcuffed, to get the police. He led police back to the apartment from which he’d just fled and they noticed the smell of decomposition right away. A look inside the refrigerator revealed human heads, intestines, hearts, and kidneys. Around the apartment they found skulls, bones, rotting body parts, bloodstained soup kettles, and complete skeletons. There were three torsos in the tub. Polaroid snapshots showed mutilated bodies, and what was going on there came clear with the discovery of chloroform, electric saws, a barrel of acid, and formaldehyde. Dahmer, a soft-spoken, apparently ordinary man, was killing men and preserving their parts, and then cutting off pieces and dissolving them in acid. In all, investigators were able to find the remains of 11 different men. When Dahmer confessed, he added six more.

(Louis Myrie/LMI)

His first murder happened when he was only 18 years old, according to American Justice’s “The Mystery of the Serial Killer.” His parents had abandoned the family home, going their separate ways, and Dahmer lived there alone for a few weeks. He wanted company, so he went out and spotted an attractive hitchhiker named Steve Hicks. He lured the man home with the promise of getting high. Hicks stayed a few hours and when he decided to leave, Dahmer smashed a barbell against the back of his head and then strangled him. “I didn’t know how else to keep him there,” he later said during an interview with former FBI profiler Robert Ressler. He discovered that he was aroused by the captivity of another human being, and then when he cut the body into pieces for disposal, he was excited all over again, so he masturbated over the body.

Later he moved in with his grandmother, but felt the compulsion grip him once again. Going to the funeral of a young man, he made plans to go to the cemetery at night and dig up the body, but thwarted in that, he began again to pick up men to bring back to his grandmother’s house. There he drugged and strangled them, and then had sex with the corpse. After that he dismembered them. One man he believed he’d beaten to death in a hotel room while intoxicated. To take care of the matter, he simply went out, bought a larger suitcase, packed the body inside, and rolled it out for disposal. While living with his grandmother, he killed four people and cut them up in her basement.

Psychiatrist Park Dietz believes that Dahmer became conditioned toward sexual excitement over corpses from sexual fantasies surrounding the mutilation of dead animals. What might have started as a boy’s curiosity about road-kill became a young man’s obsession. Killing became a sort of bonding, and Dahmer later claimed that he ate the people he liked in order to make them a part of him.

Then he got his own apartment. In an effort to create zombies to do his bidding, he tried drilling holes into the heads of his unconscious victims and injecting acid or boiling water into their skulls. He also tried to cut off the faces of his victims and to preserve them as masks, but they deteriorated. Even more macabre, he designed an altar made of skulls that he hoped to build one day when he’d killed a sufficient number of men. While he was careless at times, allowing victims to escape, so were the police, who always bought his stories. That allowed Dahmer to get away with murder again and again until he was finally stopped.

When the sole survivor told police about his encounter with Dahmer, he described how Dahmer had seemed to become another person altogether. “It wasn’t him anymore,” he insisted. “He told me he was going to eat my heart.”

Robert Ressler talked with Dahmer for two days in an attempt to learn more about his MO and his motives. He came away with a feeling familiar to him from interviews with other psychopaths, aware that the lives of their victims had been trivialized when compared against their own transient pleasure.

“There’s murder and there’s murder,” Ressler said. “There’s the kind of murder that I think the average person can understand as not justified but nevertheless understandable. For example, a man kills someone during a felony. He wants to get away. Or two guys fight in a bar and a knife comes out. There are all sorts of homicides along those lines. But when you get pure unadulterated repetitive homicide with no particular motive in mind and nothing that would make it understandable as a gain, that indicates that you have something above and beyond rational motivation. You just have evil incentive and evil tendencies. I’ve had the feeling in interviews with these people that there’s something beyond what we can comprehend.

“What’s different is that there’s no rational motivation and when they’re stalking people looking for a victim, and capturing them and taking them and locking them upsome of them would keep them for days and weeksthe emotion is gone. It’s a cool-headed decision to do all this. It’s very methodical. There’s no rage and the goal is just to get the victim and use the victim in various ways and then eliminate them.

“Dahmer killed because he was lonely. Well, a lot of people are lonely and they don’t kill other people. His solution to his loneliness was to get someone to his house, drug him, kill him, and keep the body for days at a time. Even though his defense was along the lines of insanity, I think in fact he did understand a lot of right from wrong. He went to lengths to conceal what he was doing. He did it in a manner that was designed to keep himself out of harm’s way with law enforcement. It was pretty evident that Dahmer knew what he was doing and knew it was wrong, and yet at the same time he had this element of fantasy that drove him to dismember his victims and experiment with them by putting acid into their brains. He went way beyond the realm of what a person could understand.”

One perspective on evil that uses Dahmer as a case example is Richard Tithecott’s discussion in his book, Of Men and Monsters. He shows Dahmer to be the embodiment of our own social myths. The director of the Office of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Southern California, Tithecott took a good, hard look at how we treat our serial killers in the media. “What sparked my interest initially,” he says, “was the media interplay between the Dahmer story and The Silence of the Lambs.” He shows how the narratives we construct about our serial killers actually scratch certain cultural itches.

In short, Tithecott explains how the language that we accept to depict our killers helps us to keep cherished cultural mythologies intact. Our idealization of masculinity and our need to keep it virile are the forces behind the impulse to frame the killer in a Gothic narrative: We send in heroes to grab the deviant and set things right.

Dahmerhomosexual, educated, peculiar, and not-quite-maleis the perfect foil. He’s supposedly extraordinary, an Unknownsome monster who kills and eats people. We can project onto him plenty of prejudices and fears about the dangerous Unmale Other, and feel justified in granting our law enforcers a Rambo-esque license to do whatever they must. The police become the Hand of a masculinized God, detecting and eradicating evil without the need for sympathy or comprehension. The psychiatric approach is too feminine; it yields no heroic narrative and it’s dangerous: Trying to understand the killer risks unraveling valued social structures that make him what he is. We want the sort of action that will reinforce our patriarchal myth, not analysis that might prevent the formation of such monsters.

Yet Dahmer also challenges the narrative. He’s not “set apart” in the right ways. There’s no obviously abusive family to blame, no way to completely isolate him as being discontinuous with normal, wholesome society. Thus, Tithecott finds him an excellent subject to illustrate how our killers grow out of the culture, not out of some perverse family.

Yet do we really wish to know our complicity? Do we want to be shown that our desire for killers to be utterly savage is nearly as obscene as what he actually does to his victims? That would mean looking at how we run in droves to films that depict such monsters, how we crave every gory detail the media feeds us, and how we applaud Hannibal Lecter’s cleverness in ripping off the face of an orderly to disguise himself with the skin. Tithecott claims that we want Dahmer to be like Lecterclever, sane, evilso that the FBI, not psychiatrists, can be matched against him as righteous opponents. Through the language of our narratives, we create a gladiatorial arena in which we see ourselves merely as spectators. That way, we can distance ourselves from that which our own social myths contribute to the killer’s perversions. Yet if left intact, those norms will only ensure a repetition of the same.

Thus, evil is cultural and it serves a certain psychological function that we can’t dispense with. It will continue. And just as Dahmer and Nilsen viewed their victims as nonentities who could serve a function in their lives, so do other killers believe that those they target are destined for roles in their particular games. Ted Bundy was one of these.

EVIL, PART TWO: THE HEART OF DARKNESS – REFRAMING EVIL

You Exist For Me

It was 1974 in the Pacific Northwest when a number of attractive young women came up missing. First they disappeared around Seattle and Olympia, Washington, and then one went missing in Oregon. By the time two women went missing from Lake Sammamish on the same day in July, there were already half a dozen other such reports, although there was no clear reason to link them. Yet with these latest victims, there were witnesses and a drawing was made of a man named “Ted” who had driven a tan or gold Volkswagon Beetle. Then only a mile from the lake, the remains of those two women were found several months later and now police knew they were looking for a predator.

(CORBIS)

Yet by that time he’d moved on to Utah: Four women were missing and when their bodies were found, one was bludgeoned so badly about the face it was difficult to identify her. Then there were four in Colorado, but a fifth woman, Carol Da Ronch, managed to escape from a man who had tried to kill her. She fingered Theodore Robert Bundy, a law student from Washington, and while he was in prison, an intense investigation was launched to determine if there were links to the missing girls in the other states.

Colorado got him for the murder of Caryn Campbell, but he managed to escape. He was caught but then quickly escaped again and landed in Tallahassee, Florida.

On January 15, 1978, Lisa Levy and Martha Bowman were attacked in their sorority house at Florida State University. A man fatally clubbed and raped them, clubbed another women in the head, and then fled. He also managed to viciously attack a girl in another sorority house that same night. Then less than a month later, a 12-year-old girl, Kimberly Leach, was abducted from her school and her body was found out in the woods under a tarp. Bundy was responsible for them all, and he’d been careless enough this time to leave a witness alive. He left something else that would come to haunt him: his own bite mark on the left buttock of Lisa Levy.

He was arrested and tried, with the bite mark being a key piece of evidence. The impression was clean enough to make a match to a dental impression of Bundy’s teeth. In addition, he had bitten the girl twice with his lower teeth, actually giving the forensic odontologist two good impressions to work with.

Once Bundy had been sentenced to death three times for the three brutal murders, he began to talk. He eventually confessed to 30 murders in six separate states, dating back to May 1973, although experts believe there may have been far more. “Bundy had a morality of murder,” says investigator Robert Keppel on Biography’s “Mind of a Killer.” Keppel had interviewed Bundy in prison and had made a key observation: “He thought it was okay to kill.”

Bundy also talked about his compulsions as a predator, albeit in third-person narrative. “The initial sexual encounter,” he said, “would be more or less a voluntary one that did not wholly gratify the full spectrum of desires that he had intended. And so, his sexual desire builds back up and joins … this other need to totally possess her. As she lay there, somewhere between coma and sleep, he strangled her to death.”

Michaud

Stephen Michaud, author of The Only Living Witness, talks about Bundy being hollow and empty, with some indication from Bundy’s own words that his compulsion to kill was a way to fill up the emptiness, at least temporarily. He himself said that he didn’t think of his victims as women in the normal way of regarding them, but as objects against which he took out his inner turmoil. He wanted them, felt he couldn’t have them, so he found a way to possess them. They were simply there for his use, and he attacked with whatever it would take to subdue themincluding biting. As he said to one police officer, “I’m the most cold-blooded son-of-a-bitch you’ll ever meet.”

Like a vampire, he stalked his prey and he changed his appearance to prevent easy identification. He lured his victims with his looks and charm, and with an added touch of feigned neediness. He said of himself that during these encounters some malignant portion of his personality took over, looking for satisfaction. By all accounts, he looked and acted normal; he was one of us. Yet as he said to his mother just before his 1989 execution, “Part of me was hidden all the time.”

Donald Black believes that antisocial personality disorder (ADP) such as that manifested by Bundy and other killers affects up to seven million Americans, and he claims that evidence strongly suggests that some people are just born bad. The warning signs in these people include:

- They’ve had reactions since childhood against every type of regulation and expectation.

- Resistance appears to be their driving force.

- They fail to understand or care about the difference between right and wrong.

- They lack empathy.

- They show no remorse.

Black claims that APD is eight times more common in males than females, which suggests the involvement of biological factors. However, to argue that the person cannot make decisions about what is right and wrong in a certain circumstance because of the way his or her brain processes environmental stimuli, or because of certain physiological features, requires strong proof, not just supposition. It also requires explaining why other people who share those factors do not commit crimes.

Let’s look first at other examples and then return to the psychology of the evil personality.

****

In Los Angeles, a clever manipulator named Joe Hunt persuaded a gang of former prep school chums to go in with him financially into what he dubbed “The Bombay Boys’ Club,” a commodities trading business that was destined to make them wildly rich. He used what he called “paradox” philosophy, which was a form of situation ethics: If there are any circumstances in which you’d cross a line that you claim you’d never crosssuch as to murder someonethen there are no moral absolutes. If not, it’s just a matter of believing sufficiently in the situation to take the necessary action. His method was to involve the others so deeply into badly wanting all the trappings of the finer life that they’d go along with anything he did, including murder.

When a man named Ron Levin cheated Hunt in 1984 and failed to give him a promised sum of $300,000, Hunt took a bodyguard to Levin’s home. He’d learned all about murder from underground manuals and made a 14-point “to do” list to make sure it was all done right. Somehow he left this list behind in Levin’s house. Then he and the bodyguard murdered Levin and dumped the body into a canyon outside town where it couldn’t be found.

Yet he still faced a huge debt, so he teamed up with Reza Eslaminia, the heir of a wealthy Iranian man, in a kidnap-for-ransom scheme. The man died during the kidnapping, smothered in a steamer trunk, and Hunt then attempted to forge his signature to transfer his assets to Reza.

However, at the same time some of the “boys” within the ranks were having second thoughts. First, they’d lost their initial investments, and second, they’d lost confidence in Hunt. To them, he now looked like a cold-blooded killer who’d stop at nothingeven framing or killing one of themto achieve his ambitions. They stole documents, contacted the police, and turned him in. He was arrested, tried, and in 1987 convicted of first-degree murder.

A second trial in 1992 brought him back to the courtroom to answer for his part in the kidnapping death, but he ably defended himself and charmed the jury. Nevertheless, he remained in prison for the murder of Levin, whose body was never found.

He also inspired another double homicide.

****

In July, 1989, Erik and Lyle Menendez, 18 and 21, watched the miniseries based on Joe Hunt’s crimes, “The Billionaire Boys Club.” They then devised a plan to slaughter their parents in Los Angeles. Since Hunt had schemed to make it look like terrorists had abducted and killed the Iranian man, the Menendez brothers assumed they could just blame the Mafia.

One evening, they came home with two 12-gauge shotguns. Their parents were dozing over a movie in the den of their Beverly Hills mansion. Lyle shot his father, Jose, several times, hitting him in the arm and in the back of the head, blowing it off. Erik was supposed to shoot Kitty, but when she started to move away, Lyle shot her and hit her in the leg. She fell between the couch and coffee table, but she was still alive, so he went out to the car to reload. Erik, too, had shot his mother several times in the arm and breast, blowing pieces of her around the room, yet she continued to try to crawl away. Finally several shots to her head finished her off. When it was over, Joe had taken six bullets and Kitty ten. The brothers retrieved the shell casings from the pools of blood.

The brothers then made a hysterical call to 911 to report intruders, and to the police they suggested possible Mafia connections. They had an elaborate memorial service in Princeton, New Jerseywhich included an attempt to purchase one hundred gravesites in the prestigious cemetery. Then they went on a spending spree, running up a tab of over one million dollars by the end of the year while suspicious investigators moved in on them. Proof that they had purchased two shotguns just two nights before the murder, using fake IDs, indicated premeditation. Police also confiscated audiotapes of therapy sessions between Erik and his therapist in which he confessed, as well as an incident in which Lyle threatened the man if he revealed Erik’s confession. Some of the tapes, along with the psychologist’s testimony, were allowed into evidence, and the therapist testified that the brothers had been inspired by the movie to kill their parents for money.

However, they claimed that they’d killed their father in self-defense, because he’d abused them since they were children while their mother did nothing to stop it. Lyle said that he had confronted his father about the abuse and Jose had delivered a death threat as a means of preventing Lyle from going public. He felt convinced that his parents were plotting to kill him and Erik. On the night of the murder, they’d had a heated argument and then his parents went behind closed doors. In a desperate attempt to save themselves, they’d grabbed shotguns and just started shooting. They were victims who couldn’t help their actions and they feared for their lives. They had panicked. Rather than just leave home, as young men their age ought to have been able to do, they had felt their only recourse was to kill the man who’d tormented them. They had killed their mother, they said, because they knew she couldn’t live with what they had done.

The defense used a professor to discuss the effects of psychological abuse and a clinician who interviewed Lyle in prison for 60 hours. He based his belief in Lyle’s story on his “affect,” which included shame and reluctance. The defense then used another psychologist to discuss the notion of learned helplessness, but on cross-examination she was forced to admit that the horrendous anecdotes the brothers told were uncorroborated. It was just their word. They had never reported abuse to anyone, including Erik’s therapist. Nevertheless, the defense managed to paint a sympathetic picture.

After all this, both juries hung, so second trials were scheduled in 1995. This time the Menendez brothers were retried together in front of a single jury and the judge ordered the defense not to use the battered person syndrome theory, since he believed it was not supported by proof. Jury members this time were less inclined to accept that two grown men purchased guns and planned a double murder as an act of self-defense.

In the end, the brothers were convicted of two counts each of first-degree murder, which got them both sentenced to life in prison.

A cold-blooded plan worked no better for them than it had for Joe Hunt, and in both cases, a sense of narcissistic entitlement appears to have played a significant part.

So what drives these people? Many scientists have tried to explain that. Let’s look at some of the theories.

The killers mentioned above are all examples of the classic psychopath, defined by psychologists Hervey Cleckley in 1941 and later more precisely by Robert Hare’s Pychopathy Checklist.

Cleckley published The Mask of Sanity, which listed 16 distinct clinical criteria, among them:

- hot-headed

- manipulative

- exploitative

- irresponsible

- self-centered

- shallow

- unable to bond

- lacking in empathy or anxiety

- likely to commit a wide variety of crimes

- more violent, more likely to recidivate, and less likely to respond to treatment than other offenders

Then as the concept of psychopathy evolved, the emphasis shifted from traits to behavior, and in 1952, the word “psychopath” was officially replaced with “sociopathic personality.” By 1968, “sociopathic personality” yielded to “personality disorder, antisocial type.” Yet many people working with psychopaths felt that such a label was nonspecific.

Conscience

Then came Robert Hare, a Canadian psychologist who had access to prison populations. Based on Cleckley’s work, Hare combined traits and behaviors for his Psychopathy Checklist (PCL) and wrote about it in Without Conscience. He included 22 items (twenty in the PCL-Revised), to be weighted from 0 to 2 by clinicians working with potential psychopaths. Moving away from the antisocial personality diagnosis, psychopathy was now redefined as a disorder characterized by the traits from Cleckley’s list with a few more that included:

- serial relationships (multiple marriages)

- lying

- glibness

- low frustration tolerance

- parasitic lifestyle

- persistent violation of social norms

Once they can diagnose a psychopath, clinicians know how to deal with them. First, they understand that there is no cure for this condition and it may even worsen with psychotherapy. Second, they know that these people are among the most dangerous criminals, having little human feeling for victims and no real concern for laws and social expectations. People who engage in what others call evil are generally psychopaths. Whether they’re hard-wired to be what they are, taught it, made into it from brain damage or abuse, or encouraged by some faulty socialization is still the central question, and many researchers are attempting to find the answer.

Here’s a brief list:

Creation of Danger-

ous Violent Crim-

inals

1.) Dr. Lonnie Athens, author of The Creation of Dangerous Violent Criminals, takes the approach that psychopathy or antisocial behavior develops through specific steps. He believes that people start off benign, so in an attempt to discover why only some people in a crime-vulnerable environment turn violent, he interviewed violent criminals in prisons to find out what they had in common. From his research, he determined that people become violent through a process of “violentization,” which involves four stages:

-

- brutalization and subjugation

- belligerency

- violent coaching

- criminal activity

First, the person (usually a child) is the victim of violence and feels powerless to avoid it. Then he is taught how and when to become violent (often by a person who was violent to him) and how to profit from it. It’s not long before he’s had sufficient exposure to act on it. According to Athens, if someone from a violent environment does not become violent, it’s because some part of the process is missing. Athens seems not to include an inherent tendency toward violence, narcissism, or shallow emotion as part of the antisocial scenario. It’s also clear from some of our examples that his theory will not apply to all acts of evileven of violent evil.

2) Dr. Stanton E. Samenow, an authority on the criminal personality and a former member of Reagan’s task force on crime victims, insists that the criminal’s way of thinking is vastly different from that of responsible people, and that the “errors of logic” derive from a pattern of behavior that begins in childhood. Criminals, he says, choose crime by rejecting society and preferring the role of a victimizer. They are in control of their own actions, but they assign the blame for their behavior to others. Thus, they have no insight about their intentions. They devalue people and exploit others insofar as those others can be manipulated toward ends to which the criminals feel entitled. The excitement of crime, they believe, staves off emptiness, but satisfaction doesn’t last long, so they do it again. They don’t learn because they’d don’t think correctly.

in the Nursery

3) According to Robin Karr-Morse and Meredith S. Wiley in Ghosts in the Nursery, the roots of violence develop in the first two years of life, starting at conception. “With the exception of certain rare head injuries,” they claim, “no one biological or sociological factor by itself predisposes a child to violent behavior. The research underscores that it is the interaction of multiple factors which may set the stage.” In other words, it’s not due to a negative experience, a brain disorder, genetics, or mistakes in parenting, but it could be the result of the cumulative effect of a combination of factors, along with the failure of normal protective systems in the environment.

Among those factors associated with violence, they list

- harmful substances ingested by mothers during pregnancy

- chronic maternal stress during pregnancy

- low birth weight

- early maternal rejection or abuse

- nutritional deficiencies

- low verbal IQ

- ADHD

While none are considered causal, in certain combinations and with certain dispositions, they can provoke anger, lack of anger management skills, and violence against self or others. If kids fail to connect early with caregivers, there can be problems later in life. “Babies reflect back what they absorb,” the authors say, and that notion has serious implications. If we fail to address the issues of competent child-rearing and healthy pregnancies, one in twenty babies born today will end up behind bars.

Biology of Violence

4) Debra Niehof, a neuroscientist, studied twenty years’ worth of research before she wrote The Biology of Violence. Specifically, she wanted to know whether violence is the result of genes or a product of the environment. There are several studies that indicate that the physiology of a psychopath is somehow different, that something isn’t quite right in their brains, and that they aren’t as responsive to punishment. However in Niehof’s opinion, both biological and environmental factors are involved, and each modifies the other such that processing a situation toward the end of a violent resolution is unique to each individual. In other words, a particular type of stimulation or overload in the brain is not necessarily going to cause violence in every instance. (Other young men watching The Billionaire Boys’ Club did not decide to murder their parents.)

The way it works is that the brain keeps track of our experiences through chemical codes. When we have an interaction with a new person, we approach it with a neurochemical profile, which is influenced by attitudes that we’ve developed about whether or not the world is safe, whether people are trustworthy, and whether we can trust our instincts.

However we feel about these things sets off certain emotional reactions and the chemistry of those feelings is translated into our responses. “Then that person reacts to us,” says Niehoff, “and our emotional response to their reaction also changes brain chemistry a little bit. So after every interaction, we update our neurochemical profile of the world.”

The chemistry of aggression is associated with the chemistry of our attitudes and we may turn a normally appropriate response into an inappropriate response by overreaction or by directing it to the wrong person. In other words, the person’s ability to properly evaluate the situation becomes impaired. Niehoff says that there are different patterns of violent behavior and certain physiological differences are associated with each pattern.

While most violence occurs under provocation of some type, certain people initiate it for pleasure and erotic stimulation, as we’ve seen with Bundy, Dahmer, and Nilsen. Some are psychotic, some are provoked by substances, and some use violence as a weapon. There are also killers for whom violence is the only way to satisfy their lust. They’re driven by the need for this form of arousal.

Yet even for them, the development of these behaviors results from a cumulative exchange between their experiences and the nervous system. It all gets coded into the body’s neurochemistry as a sort of emotional record. The more they succeed and feel the high, the more likely it is that they will return to this behavior.

It seems, then, that evil is a complicated human behavior for which it’s difficult to find a cause, and since we have the cognitive means for viewing evil acts from perspectives that diminish their heinousness, our capacity to commit evil increasesespecially if we believe we’re doing it for some noble purpose.

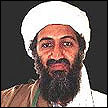

On September 11, 2001, 19 Islamic fanatics boarded four different American passenger jets. At some point during the flight, they took over. Assuring the passengers that everything would be okay, they took over the pilots’ seats. Two planes crashed into the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center, one into the Pentagon in Washington, DC, and one was aborted in a field over Pennsylvania, believed to be aiming toward another symbolic American structure.

More than five thousand people lost their lives, many jumping from floors high up in the WTC, others feeling the buildings come crashing down on top of them. Hundreds died in terror in the planes.

(AP)

The suspected mastermind of these shocking events was Osama bin Laden, a Saudi-born Islamic fundamentalist millionaire operating out of Afghanistan who had declared his intent to kill Americans with terrorist acts. He was implicated in an aborted attempt in 1993 to bomb the WTC, and the trials for those terrorists had just ended in convictions, with sentencing pending. He was also implicated in the 1998 attacks on U.S. embassies in Africa. It was his intent to wage a “jihad” or holy war, with the “fatwa,” or religious imperative, to eliminate Americans.

He had warned journalists of a “very big one,” and many believe in retrospect that he referred to the September 11th bombings. His stated purpose for these acts is to purify his Muslim land of all nonbelievers, and since history shows that American aggression has not distinguished between soldiers and civilians, he will retaliate in kind. To him, it is acceptable to kill American civilians; all are targets, and to rouse passion in his followers to do the same, he preaches that it is “the duty of every individual Muslim who is able, in any country where this is possible.”

U.S. citizens paint him as the devil; his supporters see him as a folk hero who can lead them in a righteous cause. He is a role model for extremist Islamic militants and he has high praise for followers such as the suicidal hijackers who are willing to be martyrs for the cause. So far, he has rallied thousands to his side who cheered for what took place on September 11th and who hope for more of the same.

Is evil really just a matter of how one views it? Even in the U.S., there are people who view their atrocities as actions taken in the service of a higher good.

****

In 1969, Charles Manson urged cult members to go on a killing spree. He’d formed this group from wayward kids in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, giving them a home on a ranch outside Los Angeles and a sense of belonging to something. His disciples were known as “the Family,” and his vision of “Helter-Skelter” meant that blacks would rise up to massacre whites. However, they would need the help of a white tribal leader to govern things, and Manson was the man for the job. On August 9, he sent his disciples to kill some prominent Hollywood people, telling them to make it look like the job of black militants. At the home of Roman Polanski, they used guns and knives to slaughter five people, including pregnant actress Sharon Tate. Then one of the killers used blood to write the word “Pig” on a door.

The following night, they did the same to a married couple, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. They carved “War” into the man’s chest and used blood to write “Death to Pigs” and “Healter Skelter” on the walls. Then they had a snack before leaving.

One of them, Susan Atkins, spilled the beans while in jail for another crime, and the killers were arrested, tried, and convicted.

****

A man from Decker, Michigan, quietly drove the yellow Ryder rental truck through the streets of Oklahoma City on the morning of August 19, 1995two years to the day of the tragedy at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas that ended the lives of 83 people. He parked outside the Alfred P. Murrah government building and walked away. By the time the 4000-pound bomb exploded at 9:02 a.m., he was blocks away, with earplugs hindering the noise of a huge building collapsing. Then he got into a beat-up car without a license plate and drove away. He considered himself a hero, without a thought for the 168 men, women, and children who were dead or dying, and the more than 500 who would turn up injured. To him, they were “collateral damage,” just the price to be paid for sending the government a dramatic message.

He was caught, tried, and executed, and his actions had the unsettling effect of letting the American people know that terrorists lived among us.

McVeigh was an ordinary person who had developed an idealism that demanded violence. Manson’s followers were just kids off the streets who wanted to play their role in his “family.” Under other circumstances, any of them might just as easily have been pro-social rather than antisocial. Let’s look at what makes the difference.

Perpetrating harm on others is often carried out by people who would not think up the acts but who somehow get inspired by someone else to follow through. Many of the people who carried out Hitler’s plan believed they were following a sacred mission, yet would likely never have done the same things in another context. Manson’s followers thought they were carrying out the plan of a godlike man and were willing to murder and even cut a fetus from inside a woman’s stomach.

(CORBIS)

In the massacre of an entire hamlet in Vietnam in 1968, Lt. William Calley claimed that he was following orders. According to some counts, he was responsible for giving the order to kill between 400 and 500 civilians in a matter of three hours who were unable to defined themselves, slaughtering women, babies, and the elderly without mercy. Some of his men raped and killed with abandon, and then afterward took a break for lunch. By their measure of success in that strange war, a body count of that magnitude was cause for celebration. They had been raised in families where different values prevailed, but in the moment, in that place, they did what seemed right. In Army circles, they were a success. Back home, they were viewed as savage killers.

Fred Katz, sociologist and author of Ordinary People and Extraordinary Evil, examined the mechanisms of our ability to start out innocently and by gradual increments get into position to enact real evil.

One possible causal factor, Katz points out, is that we tend to separate out truly atrocious evils such as the Holocaust and call them unique. He believes that this is a mistake, because it prevents us from seeing how evil grows out of the ordinary. While psychopathy and sadism are linked to some evil acts, there are no special traits or behaviors that might set many malicious people apart as “monsters.” Most evil that occurs is done by ordinary people, and ironically those very same behaviors can assist us in living humanely. Defining evil as “behavior that deliberately deprives innocent people of their humanity, from small scale assaults on their dignity to outright murder,” Katz focuses on how people actually behave. Evil can beguile people in a way the makes them see it in a different lightone that permits them to manifest it. Hitler may have devised a wicked plan, but ordinary people zealously carried it out.

Here’s how:

- Evil can be made acceptable through certain frameworks, such as nationalism or the service of a vision, or “for science.”

- People addressing immediate problems may not see the larger context but may still contribute to its progress with their mundane activities.

- It can be presented as part of a career, which involves the person through small, incremental steps as merely advancing himself.

- It can be done in obedience to an authority who commands it.

- It can be diffused throughout a culture so that no one’s cruelty stands out, and some evil acts within a culture of cruelty can even be rewarded within that culture. Taking initiative to do evil in such a context enhances one’s status.}

Katz talks about how packaging and “riders” quietly organize life toward certain ideas and behaviors. Riders link one sector of life to another, the way Hitler’s grandiose vision of racial purity and German superiority linked politics, economics, social life, and even religion. Within such visions, evil can become legitimate: operating a crematorium served the vision and made the operator somewhat heroic. People loyal to a cause can harm others when they understand it as part of the cause. It’s a “higher” good and those participants even view themselves as acting selflessly.

One thing that Katz does not discuss but which is often at play in people feeling okay about harming others is the notion of Groupthink. Someone designs a stance and others join in. Soon it’s “us” against “them.” We’re morally right, they’re morally wrong. Groupthink creates insular thinking and exaggerates external threats. The group leader implies that there is no better solution than his, there’s pressure within for homogeneity, and no one is allowed to argue or question. Anyone who does gets vilified and mocked. It’s a collective rationalization with self-appointed “mindguards” that helps stereotype people outside the group and make it okay to sacrifice or get rid of them. There’s no real survey of alternatives or of the risks involved in the chosen option, and the boundaries soon close in and calcify. It’s insidious and self-blinding.

Katz does show that atrocities such as My Lai that occurred in Vietnam had a similar dynamic. “The Vietnam package of values,” he writes, “was a rearranged version of the peacetime American values on which most soldiers were brought up.” They knew not to kill innocent people, but they were able to reframe the Viet Cong as part of “them,” and thus not innocent, even if civilian. The priority not to kill was subordinated to other priorities within the same package.

The rider, Katz explains, places an imprint on every value in the package. When killing the enemy is the rider, as with bin Laden, Manson, and Lt. Calley, it reorganizes the values in the package. The measure of success depends on the rider, and the rider on the ultimate vision. For Hitler, national shame had to be avoided, national pride and grandeur promoted. For bin Laden, the world will only be healed when Americans are eliminated. Those visions arrange priorities and fuel passion in the masses to manifest the elements of the vision.

There is no doubt that there are people who do love to inflict torment and are happy for the licenses of war, but there are those who do not love to do so but who will do so anyway when the context inspires them. It’s not the torture they love but the vision that such acts serve. According to Katz, they may be committed to only certain parts of a package, but will nevertheless carry on other activities demanded by the package as well. They go along, carrying out evil without being committed specifically to evil.

In other words, a physician who is not committed to killing human beings may, when posted to Auschwitz, participate in killing them if the package allows him to reframe the act in a nobler way. Exterminations, for example, were referred to as “special actions,” and the language helped those who participated to gradually adjust. Outside moral codes fade away as the context defines what is right and wrong. In a culture of cruelty, others can be exploited in any manner one wishes. The prevailing values allow it, even encourage it, and some within that culture flaunt their particular ability to be cruel. It escalates and becomes commonplace.

“Cruelty became the distinctive content of the informal culture among the Auschwitz guards,” Katz remarks. “A premium was placed on creating cruelty and treating it as a from of creative art.”

It’s one thing to be raised within such values, and therefore to not know better; it’s quite another to adopt them after one has already known another way. For such people, there is no excuse for doing evil.

****

Another example of people who behave according to the dictates of a culture of cruelty is the training of the henchmen for Roy DeMeo, a one-time butcher’s apprentice and the most feared hit man for the Gambino crime family. He’d grown up a bully, ambitious and opportunistic. Raised in a middle-class family, he was nevertheless strongly impressed with the shiny cars of the gangsters and soon decided to make his living as a loanshark. Eventually he became a member of New York’s Gambino family, doing his first hit at age 32, and quickly thereafter he selected his associates in murder. Once a person killed, he believed, that person could do anything.

Because he could stomach it and because he thought it proved his power, he devised a specific form of getting rid of someone, which came to be known as “the Gemini Method.” He trained a crew of young mensome teenagersto participate in a horrifying “dis-assembly” line. The target person would be taken to a house or would be invited into DeMeo’s Gemini Lounge (or in one case, the meat department at a supermarket). He’d be shot by one person, wrapped in a towel by another to prevent blood from messing the place up, and repeatedly stabbed in the heart by yet a third person to quickly decrease blood flow. Then he’d be cleaned up, allowed to “settle” for 45 minutes, drained of blood, laid out on a swimming pool liner, beheaded and hacked into pieces that were packaged like meat and tossed into a dump. Just like taking apart a deer, DeMeo told his gang.

Such “disappearances” happened frequently and systematicallythere were perhaps as many as two hundredand those five men involved in the assembly line said they got a kick out of it. According to Gene Mustain and Jerry Capeci in their account, Murder Machine, “They used to say killing made them feel like God.”

Even worse are those who derive their satisfaction from exploiting and harming children.

(CORBIS)

Some predators view children as mere objects for their erotic stimulation. Albert Fish, Marc Dutroux, and Wesley Allan Dodd all abused and harmed children in some manner, but Fish was probably the worst of the lot.

A religious fanatic and sadist, early in childhood he developed an obsession with punishment. Although married and the father of half a dozen children, he secretly beat himself (or got his children and their friends to beat him) with spiked paddles. He also stuck needles into his groin (leaving some there), threaded rose stems into his urethra, and lighted alcohol-soaked cotton balls inside his anus. Among his many paraphilias was coprophagia (consuming human feces) and mailing obscene letters. In visions he received commandments that made him believe he was Abraham from the Bible, and just as Abraham was called to sacrifice his only son to the Lord, Fish realized he would have to kill childrenor at least to castrate young boys.

Fish’s first wife had long ago left (after keeping her lover hidden in their attic) and he began to travel to distant places where he married three more times and may have molested over one hundred children in twenty-three states. He actually claimed that the total was more like 400, and some of these children he mutilated and killed. The one that led to his arrest in New York in 1934 involved a twelve-year-old girl named Grace Budd.

Fish was 58 at the time. Passing himself off as “Mr. Howard,” he approached the Budd family with the intent of luring their eighteen-year-old son to his home under the pretense of giving him employment. Then he spotted Grace and chose her instead. He ingratiated himself with the family until they trusted him, and then told Grace that he would take her to a birthday party and she willingly went with him. Her family never saw her again.

Six years went by and for some inexplicable reason, Fish sent an anonymous note to Grace’s mother. He wrote about how he had taken Grace away, strangled her, and then dismembered her. Then he claimed that he had cooked certain pieces of her and consumed them.

It was the stationery that gave him away. A dogged investigator traced it to Fish, and when the self-professed cannibal was arrested, he confessed in lurid detail. In the stew he made of Grace Budd’s flesh, he had added carrots and bacon strips, and as he savored it over the next several days, he masturbated over his grisly deed. His first murder, he said, took place in 1910 when he killed a man in Delaware. Believing himself to be Christ, and obsessed with sin and atonement, Fish admitted to the murders of three other children, although some experts place his death toll as high as fifteen.

Despite obvious insanity, the jury sentenced him to death, and on January 16, 1936, he was sent to the electric chair.

****

Westley Allan Dodd was a predator. He fantasized about his future victims and made elaborate plans for what he would do with them. Caught while attempting to abduct a six-year-old boy from a movie theater restroom, he was investigated for his involvement in the murders of three other boys in the Vancouver, Washington, area. Two brothers, Cole Neer, 10, and William Neer, 11, were found stabbed to death in a park. Less than ten miles from there, a 4-year-old was murdered and dumped. Dodd confessed to all threeobviously delighting in the sadistic details.

Searching his home, police found a torture rack, photos of his victims, and a disgusting diary recording his crimes and detailing his gruesome plans for other victims. His MO involved befriending the children with gifts and coaxing them to go with him. Although he was stopped when he was 28, he’d already been molesting young boys for 15 years.

****

Some child abusers also get involved with child pornography, as was the case with Marc Dutroux in Charleroi, Belgium. From the mid-1980s until he was caught in 1996, he developed an international child pornography and prostitution ringalthough he himself had three children. He supported them and his second wife by kidnapping young girls and selling them into prostitution across Europe.

In 1989, he was convicted in the rape of five young girls, but after only three years in prison was granted early release. Soon more young girls disappeared. As it turned out later, he kept them imprisoned in empty houses that he owned, and though police actually searched one, they failed to find the secret dungeon in which the girls were kept.

When police raided Dutroux’s home in 1996, they found 300 pornographic videos of children and a concrete dungeon that Dutroux had built that held two girls. One was 12 and one 14, and they’d both been sexually abused. They’d been grabbed off the streets, drugged, thrown into the dungeon, and forced to pose for films. One of them had been there for over two months.

Two other girls, both 8, had died while imprisoned. When Dutroux had been incarcerated for a month for car theft, they had starved to death and he’d later buried them in his backyard. With them was the body of one of Dutroix’s accomplices, whom he said had been buried alive as punishment for letting the girlshis source of incomestarve.

Then there were two other girls, 19 and 17, who had turned up missing and who were linked to Dutroux. They were buried under concrete in a shed next to another of his houses.

During the investigation into these four deaths and the many kidnappings, police discovered a sex ring, which included Dutroux’s second wife and a businessman who had entertained government officials at an orgy. Getting Dutroux to trial for these crimes, however, proved difficult. Over four years later, he still had not been formally arraigned.

The human mind has the capacity to reconceptualize almost anything, even the most atrocious acts against others. It’s called reframing and it simply means that an act in one context that clearly is evil can be viewed in quite another context as noble and heroic. Americans thought that the attacks on the World Trade Center were an unmitigated evil that would be recognized as such around the world. Many were astonished to see films of people in Afghanistan cheering over this victory for fundamentalist Islam. They had struck a telling blow against Satan.

How can a single act be both evil and noble? How can a single person who views harm to others as evil one day call it good? It depends on the context, and that makes it possible for people raised within a certain culture to engage in what that culture views as evil, because they are participating in a context in which other values prevail. Thinking is malleable and the pressures of peers or an ideology can affect conduct and values.

Yet that’s not a definitive explanation for evil acts. While each of the people described above had a way to reframe what they were doing to make it seem less wicked and even to ennoble it, there are some who don’t care what anyone thinks: They identify with symbols of pure evil and just go all out. We’ll encounter such people in Part 3, and try to get to the roots of the evil imperative.

Athens, Lonnie. The Creation of Dangerous Violent Criminals. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Everitt, David. Human Monsters. New York: Contemporary Books, 1993.

Hare, Robert D. Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths among Us. New York: Pocket, 1993.

“His Vow to Kill Americans: An Exclusive Interview with the World’s Most Wanted Terrorist,” ABCnews.com, August 20, 2001.

Horton, Sue. The BBC: Rich Kids, Money, and Murder. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

Janis, Irving. Groupthink, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1992.

“Jeffrey Dahmer: Mystery of the Serial Killer,” American Justice, A&E., 1993.

Katz, Fred E. Ordinary People and Extraordinary Evil. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1992.

Karr-Morse, Robin and Meredith S. Wiley. Ghosts From the Nursery: Tracing the Roots of Violence. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1997.

King, Gary. Driven to Kill. New York: Pinnacle, 1993.

Mustain, Gene, and Jerry Capeci. Murder Machine. New York: Onyx, 1992.

Newton, Michael. The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. New York: Checkmark Books, 2000.

Samenow, S. E. Inside the Criminal Mind. New York: Times Books, 1984.

Simon, Robert. Bad Men Do What Good Men Dream. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1996

Springer, John. “The First Mention of a Possible Suspect: Islamic Terrorist Osama bin Laden,” Sept. 11, 2001.

“Ted Bundy: The Mind of a Killer,” A&E Biography, 1995.

Tithecott, Richard. Of Men and Monsters. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997.