Dr. Steven Egger: Expert on Serial Murder — Career Overview — Crime Library

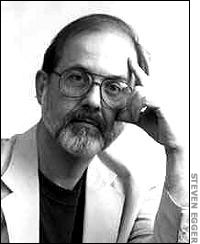

He was the first person in the world to write a dissertation on serial murder, and he has managed to interview several infamous killers. Plenty of criminology students who read about serial killers know his name, and in the future he may well make one of the most substantial contributions to this specialized arena of knowledge. Dr. Steven Egger is Associate Professor of Criminology at the University of Houston at Clear Lake in Texas, as well as Professor Emeritus of Criminal Justice at the University of Illinois at Springfield. His resume is impressive, as are his observations about the criminals he has studied.

Besides being a noted scholar, Egger has also been a police officer, a homicide investigator, a police consultant, and a director of a law enforcement academy. He received his Ph.D. in Criminal Justice from Sam Houston State University, having had exposure to the investigation of serial murder before the phrase “serial killer” was even common usage. For more than two decades, he has devoted himself to research in this area, lending valuable advice during one period as the project director of the Homicide Assessment and Lead Tracking System (HALT) for the state of New York, which was the first statewide computerized system designed to track and identify serial killers.

Having gained international renown in the field, Egger has lectured on the investigation of serial murder in Spain, England, Canada, and the Netherlands, as well as all over the United States, including a recent conference devoted to serial murder offered by the FBI. Gathering together what he has learned since the late 1960s, Egger has authored three books, The Need to Kill: Inside the World of the Serial Killer, The Killers among Us: Examination of Serial Murder and its Investigations (2nd ed.) and Serial Murder: An Elusive Phenomenon, with other books in progress. Egger and his wife, Kim, who concentrates on the interface between law and psychology, are currently at work together on a comprehensive database of killers from all over the world and they will soon publish an encyclopedia of serial murder in the United States with more than 800 entries from their database of more than 1,300 serial killers.

In a farmer’s field just outside Ypsilanti, Michigan, the body of a young woman was discovered in August 1967. She was badly decomposed, so her identity was initially a mystery, but authorities soon learned that she was the co-ed from Eastern Michigan University who had been missing for three months. A suspect was developed, but leads fizzled out and the case remained unsolved. No one realized it was the first in a series that would terrorize the area for the next two years.

The following year, another co-ed was murdered and unceremoniously dumped, and then in 1969 there were five more female victims, the youngest of which was only 13. Newspapers linked all seven, pressuring area police to arrest someone and bring this spree to an end. Whoever was perpetrating these crimes had clearly stepped up his pace, raping, stabbing, shooting, and mutilating girls who lived near, worked at, or attended EMU or the nearby University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. It was possible that one person had committed the crimes, but no one was sure.

Most of the bodies were left out in the open where they would be easily discovered, and eerily, while the police were investigating the burned-out barn foundation associated with two of the killings, someone placed flower blossoms close by, corresponding to the number of victims. It could have been a prank or it could have been the killer.

Fed up with the police, a citizens’ group scraped together funds to invite nightclub psychic Peter Hurkos to come and solve the mystery, and he predicted another murder would occur, although he could not say just when it would happen. Shortly after, the body of 18-year-old Karen Sue Beineman was dumped within a mile of Hurkos’s hotel, as if in defiance of his visit. A few weeks later, the police arrested a young elementary education student, John Norman Collins.

“I had been a police officer for about a year,” Egger recalls, “and they asked me to be a press liaison between the police department and the sheriff’s department, and thereafter I was assigned as an investigator to the case. We had two more deaths before we had the Beineman murder and that’s when we arrested Collins. It wasn’t even called serial murder at the time. I think the media called it mass murder or multiple murder.”

Hair samples from the victim’s clothing matched clippings from Collins’ car and the floor of the crime scene, which influenced the jury’s decision to convict Collins of Beineman’s murder. The state of California suspected him in an eighth murder as well, for which there was strong physical evidence from a trip he’d made there, but they declined to extradite him, so he received life in prison in Michigan. Egger saw him face to face when they initially arrested him.

“I was in the same room when they brought him in for an interview,” he says. “He never confessed to the crime. We had fibers from his uncle’s basement, who turned out to be a corporal in the State Police.” When asked for his impression of Collins, Egger remarks, “I just felt that he was deranged.” He would eventually learn more about such killers and come to understand the nature of a psychopath, but with this initial case, he also had an experience with the psychic.

Among the most curious aspects of this case was the involvement of a famous psychic, although Hurkos had also taken part in the Boston Strangler investigation in 1963. He had written that he’d selected a different man for that series of murders than the one police had arrested (Albert DeSalvo), and he believed they’d been wrong to end the investigation. However, the general perception is that Hurkos had largely botched that case, and had run away when it was clear he’d offered nothing useful.

In the series of murders in Ann Arbor/Ypsilanti in which John Norman Collins was suspected (he was convicted of only one), Hurkos made a variety of observations and pronouncements, a number of which were uncannily correct (at least, according to his own account), and a number of which were entirely off base (according to other accounts). As part of the investigation, Egger had the chance to spend some time with Hurkos.

“He wanted to see the town,” Egger recalls, “and he was on a comeback with his career. Of course, he had been very active with the Boston Strangler case, and the chief had said that some of the relatives of the girls demanded that he bring in a psychic, so he’d brought in Peter Hurkos.

“We chaperoned him around for a couple of days, and during that time, Karen Sue Beineman was found in a ravine near the city. I turned and asked him, ‘Why didn’t you tell us about it?’ He said, ‘You didn’t ask me.’

“I have always been skeptical of psychics. In my estimation there is no empirical evidence that a psychic has ever really helped in a criminal investigation. There are a lot of cops who think they have, and of course in a serial murder case, psychics come out of the woodwork and talk about offering their expertise pro bono. It’s good publicity for them. If they even get half right then they claim they hit.”

Hurkos, apparently, did the same. While Egger did not again have such an encounter with a police officer, he would have the opportunity to meet more serial killers — but after they’d been convicted.

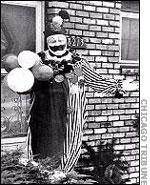

as a clown

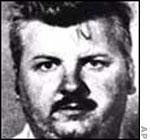

A killer in Des Plaines, Illinois, near Chicago, lured young men to his home and tricked them into allowing him to bind them with a special rope device. Once they were helpless, he would then rape and strangle them. No one would have guessed that John Wayne Gacy, a good neighbor and successful businessman who entertained sick children as a clown, was capable of the kind of deviance he displayed, but even as he threw large parties in his yard, he had nearly 30 of these victims buried in the crawl space beneath his house.

Near the end of 1978, when Rob Piest went to speak to Gacy about a summer job in construction and disappeared, the Des Plaines police put surveillance on Gacy and finally arrested him. He confessed, but tried to blame an alternate personality for the deeds. He also blamed the victims, saying they had come on to him. His final toll was 33, and despite his bid for an insanity defense based on an inability to control himself, he was found guilty and sentenced to die. While Gacy was on death row, Egger had a negative encounter with him.

“I talked to Gacy briefly through the bars,” says Egger. “He had seen me on TV and he came across with some profanity that I had not heard yet — all these adjectives and adverbs mixed together, and then he ended by calling me an expert. I turned to him and said, ‘John, I’m not the serial killer, you are. You’re the expert.’ All of death row cackled, because they did not like John Wayne Gacy.”

Egger’s comment got a rise out of the “I-57 Killer,” Henry Brisbon, who was responsible for several murders along I-57 south of Chicago from 1972 to 1976, including a couple he shot to death after forcing them to “kiss their last kiss.” While serving a long sentence at Stateville Correctional Center, he reportedly got into a fight with another inmate, Richard Morgan, and killed him. For that, he received a death sentence. Then he got into a fight with Gacy and tried to stab him, but did not succeed in killing him. This incident occurred just a few months before Egger arrived.

“He was willing to talk to me and to shake my hand,” Egger says about the dubious honor. His most lengthy conversation with a notorious serial killer was the series of interviews he had with Henry Lee Lucas.

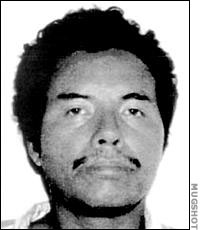

In Stoneburg, Texas, on July 11, 1983, the police arrested a one-eyed drifter named Henry Lee Lucas for the illegal possession of a firearm, although they suspected him in more serious crimes. Lucas was 46 at the time, and associated with two women, who were both missing. He’d known Kate Rich, 82, and witnesses had seen him with her the day before she disappeared. The younger one, 15-year-old Becky Powell, had been Lucas’ companion. They had rolled into town together, but she was nowhere to be found. He said she had decided to return to Florida, but there was something about Lucas that authorities just did not trust.

After four days in jail, Lucas called to the jailer to admit that he’d done “some bad things.” He admitted that he had killed a number of people. After he was charged with the murders of Kate and Becky, he provided plenty of evidence, including showing the police precisely where Becky’s decomposed remains were buried. When Lucas was arraigned, he admitted to Kate Rich’s murder, but then said that he’d killed at least 100 more. The revelation created instant headlines, and Lucas seemed pleased with his notoriety. He offered interviews, and the more he talked, the more open cases he closed. At an unprecedented event, lawmen came in from all over to fill an auditorium for a day to find out what he might know about their unsolved cases.

Lucas confessed in more than 350 cases before he suddenly recanted. No one knew quite what to make of a killer confessing to so many crimes he did not do, but then he insisted that he’d been forced to recant. However, now people began to doubt his credibility. He clearly had manipulated and lied to get favors and attention, but he also seemed to know a great deal about some of the murders.

While it was clear that Lucas had killed his mother during a fight with her when he was a young man, and had recently murdered Becky and Kate, none of the other murders was so resolved. Even the case for which he got the death penalty, a woman known only as “Orange Socks” for the clothing she was wearing when found, there seemed to be evidence in recent years that he could not have committed that murder. In fact, his death sentence for it was commuted by then-governor George W. Bush.

Some criminologists believe Lucas was responsible for 40 to 50 murders, but no one knows for sure, because he declared that he’d set out to fool the police and believed he’d done a good job. During that time, as many people clamored for interviews with Lucas, Egger actually managed it. “I got access to him through a friend of mine who had been a producer on 20/20. He got me a connection with a woman who was involved with Texas Child Search. She had already interviewed Lucas and in 1983 she took me along and even showed me how to set up the video recorder.”

He spent more than 40 hours with Lucas, taking as much advantage of the opportunity as he could. “I would get up at three o’clock in the morning and leave Huntsville to go to the Williams County Jail in Denton, Texas, and I would interview him in the morning before any of his other interviews. The interview I got was pretty good, except that the woman who had gotten me access brought along one of her friends who was a freelance reporter. We stopped at her house in Austin on the way back to get my car and she wanted to know if she could make a copy of the tape. I really didn’t have a lot of control over it, so I allowed her to make a copy. About a year later, a fellow by the name of Joel Norris used my interview to promote a book of his called The Confessions of Henry Lee Lucas. It came with an audiotape shrink-wrapped around, and that was my interview, with my voice dubbed out. In some instances, this can be a pretty cutthroat area of research.”

Nevertheless, Egger spent a lot of time with a killer and was able to develop a good impression.

“To me,” says Egger, “Lucas was the epitome of how you produce a serial killer. He had gender confusion until he went to school, because his mother dressed him in a dress and he had long hair, a fact that was verified by NPR when they interviewed one of his half-sisters. She showed them a picture of Henry in long hair and a dress. He was forced, as far as I could tell, into watching her have sex with her clients. The man whom he thought was his father (and I think that’s questionable) had lost both of his legs and so he lived with this amputee, his brother and his mother’s boyfriend, who taught him about the birds and the bees by showing him how to have sex with animals. He said that he found it easier to have sex with dead animals, and I think that’s why he became a necrophiliac.”

Among the cases that were attributed to Henry Lee Lucas during the period when he was claiming so many was the death of a police officer that initially was declared a suicide. “Lucas was convicted of killing a police officer in Huntington, West Virginia,” Egger said, “an incident that had been declared a suicide twice — which was bizarre because the man was found sitting in front of his car, handcuffed, with a note to his wife and family, and he was shot in the forehead. It’s possible, but most people don’t commit suicide that way. Lucas directed the police to the spot where they found this officer and he pled guilty and was given 75 years.”

As to how he managed to convince people of murders he actually did not commit, Egger says, “He was real quick to pick up words that I don’t think he understood, but he could grasp them in terms of context, and about more than half of the time he was right. He wasn’t very well-educated — he never got out of the fourth grade — but he was extremely street smart.”

With the information he got from Lucas, Egger was able to assist law enforcement in building a timeline of Lucas’s activities. “I helped the [Texas] Rangers with a chronological analysis of where Lucas and Toole had been tracked through NCIC. The Rangers used it in some of their training.” The information helped Egger as well to clarify some of his own ideas about the investigation of serial murder.

When asked about his own estimate of the number of Lucas’s murders, Egger has a response: “I think Lucas probably killed at least 60 people. He was convicted of eleven. I think he probably started killing very early. His first kill was when he was about fourteen. He was raping a girl and decided he couldn’t afford to have a witness. And he continued to tell me that the reason that he killed was that he didn’t want to have a witness.”

Even if he did not kill that many, Egger still thinks that “he is nevertheless the epitome of the production of a serial killer,” based largely on incidents that Lucas reported to Egger that seemed to have contributed to his sense of anger and hurt. “He was out with his brother when they were seven or eight and they were making some kind of a tree house. His brother was using a knife to cut a thick grape vine and he slipped and stabbed Lucas in the eye. So they rushed him to the hospital and of course in rural West Virginia they didn’t have the best of doctors. His eye was sutured up and a bandage put on there. So he went back to school a couple days later and he was standing in line for recess. Kids were horsing around and a student reaches back to kind of hit another student and jammed her elbow in Henry’s eye, so his eye was basically decimated. They gave him a prosthetic glass eye but the problem was they had not stitched up the tear duct properly, so here’s a guy with a glass eye and matter coming out that looked like puss. You can imagine the kind of treatment the kids gave him on the playground and in school. So he became a pariah. He told me that the only thing that he did was go to the movies with his brother. And I guess the movies gave him the idea to travel because his goal when he left home was to simply travel.

“But he also repeatedly talked about his hatred of prostitution. For Lucas, there was no difference between prostitution and women. And he talked about a general hatred because of the way he had been treated. He said he was treated like the dog of the family, having to eat off the floor, having to eat scraps, having to make bootleg liquor.”

In addition to Lucas, Egger was able to interview his sometimes partner, Ottis Toole, who was in prison at the same time in Florida for another series of murders. It was a unique opportunity to hear about the same murders from both people on a rare sort of killing team.

Ottis Elwood Toole was an arsonist who also enjoyed mutilating corpses and claimed to be a cannibal (possibly for effect). He’d met Lucas in a Skid Row rescue mission in Jacksonville, Florida, and they hit it off and became lovers. Toole was a grade school dropout with an IQ that was borderline mentally retarded. Abandoned by his alcoholic father, he grew up in the custody of his mother and sister, whom he claims dressed him as a girl. His mother supposedly was a religious fanatic, while Toole’s grandmother had been a Satanist who took him to help her dig up graves for body parts. Like Henry Lee Lucas, he committed his first murder at age 14, but in this case, he ran over a traveling salesman with his own car. Most notably, Toole confessed to killing Adam Walsh, the son of John Walsh, who went on to develop the TV show America’s Most Wanted.

“Toole was more formidable when I first met him,” Egger recalls. “I was doing some training down in Tallahassee for a friend of mine, and he put me in contact with the assistant warden at Stark, their death row. I wanted to meet Toole because I had spent all this time with Lucas, and it was set up to take place on a Saturday.”

Egger was left alone for several hours with this strange little man who claimed to kill and eat people. Given his bizarre background, it was no surprise that Toole seemed to want to make an impression. “Toole walked in, sat down and slammed his hand on the desk. He wore a ring, which vibrated and it screwed up my recording. Current Affair had just been there the week before, so he says, ‘I suppose you want to hear about my barbeque sauce.’ I said, ‘Ottis, I don’t need this shit. I just don’t need it. I’ve talked to Henry.’ And he looked at me and said, ‘You haven’t talked to Henry.’ And I opened my book, which Lucas had signed for me, and said, ‘That’s Lucas’s signature. You recognize it?’ He said, ‘Yeah. Maybe I will talk to you.’

Even so, he did not offer much. “Out of two hours,” says Egger, “I think I got about 15 minutes of accurate information. Ironically, I wasn’t able to verify it — his claim that he had been abused by two different stepfathers. I guess the reason that I placed some validity in his comments about that was that he didn’t seem to be using it as an excuse. He just talked about the fact that he’d had a lousy childhood.”

Asked for his impressions of Toole, Egger offered, “I don’t think he was very smart. He was definitely the follower in the Lucas/Toole situation. He probably came across a little stupider than he really is, which means he was a bit cagey. But I don’t think he was smart enough to use that to his advantage very often.

“As Park Dietz said, there’s a theory that these people have such terrible childhoods but we’ll never be able to know because you can’t do a decent study on it. All of these people who have been convicted claim they were abused as kids as a way to mitigate their sentence or their responsibility. If I could figure out a way to research that issue I would, but you just can’t believe these people.”

Nevertheless, Egger does what he can and he participated in some of the early groundbreaking decisions. In fact, that’s what led him to write his dissertation on serial murder.

At a U.S. Senate subcommittee meeting, a number of people from law enforcement and criminology presented a case for acquiring funds for a computerized database, to assist with the investigation of serial murder. John Walsh was among them, testifying about his murdered son, Adam, and true crime writer Ann Rule described serial killers who had been mobile enough to go from state to state. A way to link cross-jurisdictional crimes like these could save many lives.

The Department of Justice then hosted a conference at Sam Houston State University, inaugurating the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program (VICAP). Under the auspices of the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, the FBI would run it out of Quantico. Egger was a witness to this process, and his participation inspired his dissertation, “Serial Murder and the Law Enforcement Response,” written while he was a doctoral student at Sam Houston State University.

“They had a grant from the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime,” says Egger, “and they were developing the protocol for psychological profiling based upon the interviews that Ressler, Hazelwood and other FBI agents did in the prisons. Here I was studying something that didn’t even have a label, in which I had been involved many years earlier. I realized that no one was doing any research on it. The only published information at the time was a couple of articles, all recent, in the FBI’s law enforcement bulletin. So I decided to write a qualitative dissertation where I developed my own methodology on case studies, which I then used in the revised edition of my second book. I also coined the term ‘linkage blindness’.”

What he means by a qualitative research, which is common in the applied social sciences when researchers wish to immerse most fully in their subject matter, is a method for data collection and analysis that involves allowing the phenomenon under study to shape the queries and procedures. This involves viewing the subject just as it is, rather than subjecting it to pre-set formulas for analysis. It’s described in its raw form, so there’s no danger of limiting its complexity. The researcher risks getting swamped in details and losing focus, but the research benefits the subject’s fullest dimensions.

“My argument,” says Egger, “is that if enough researchers use that format, then we could come up with a fairly extensive database from which we can draw inferences. I used the work of a gentleman named Yin who has done a lot of qualitative research. Then I looked at Gibbon’s typology, and I extrapolated to serial murder and built my own categories.”

He may not have realized it at the time, more than 20 years ago, but he was embarking on a career devoted almost entirely to serial murder. As such, he would develop an approach to speaking to these offenders whenever he had an opportunity, and he got one with another Texas-based killer.

Before approaching an offender, Egger thoroughly prepares. “I try to know as much about the case as I can ahead of time,” he states. “One of the first things that I try to do is verify what I have read in the media. I have frequently found out from what the killers have told me that the media’s rendition is not very accurate.” In the case of Angel Maturino Resendiz during the late 1990s, the story was almost entirely limited to what the media reported.

On March 23, 1997, in Ocala, Florida, 19-year-old Jesse Howell was bludgeoned to death with an air hose coupling and left near a railroad track. Thirty miles away, his girlfriend was found buried in a shallow grave. She had been raped and strangled. These crimes remained unsolved.

Five months later in Lexington, Kentucky, two more people walking along a track were attacked. Then in 1998 in Hughes Spring, Texas, 81-year-old Leafie Mason was beaten to death with a fire iron, and since she had resided 50 yards from the Kansas City-Southern Rail line, authorities wondered if there was a link among these crimes. Then a female physician, Claudia Benton, was raped, stabbed and bludgeoned in her home in West University Place, Texas, near the tracks, while a middle-aged couple was killed with a sledgehammer in a church parsonage, also near tracks. Of four more victims in Texas killed around the same time, three lived near the railroad.

The “Railway Killer” evaded capture, but when police processed a fingerprint inside one of the victims’ stolen vehicles, a fingerprint on the steering column matched Resendiz, an illegal immigrant from Mexico, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. The police asked his sister for help and Resendiz finally surrendered. He confessed to nine murders, but the police believed he was guilty of at least five more. He went to court with an insanity defense, but was convicted of the murder of Dr. Claudia Benton and sentenced to die by lethal injection. As his execution date approached, his attorneys again argued that Resendiz is insane. They say that he believes he is a man-angel and that the lethal injection will merely put him to sleep.

Egger’s experience with interviewing Resendiz affirmed in his mind that psychosis was a viable diagnosis. “He said that he was killing these people because they were either worshipping Satan or performing abortions. I asked him how he knew that and he said he could feel a tingling across the back of his neck when he got near them. But he could have been blowing smoke at me. I didn’t know the guy that well and he was willing to talk to anyone. The lawyer did not want me to talk with him but he overruled his lawyer. If he believes what he told me, then I think he is probably psychotic, but I have no way of proving it.”

Among the subjects they discussed was Resendiz’s early experience. “He talked about a lousy childhood and about being abused in the street. He was kind of adopted on the street by a guy who abused him for two or three years. The difference [in my experience] between Resendiz and Lucas is that I had more time to go back over things with Lucas. I would ask him, for instance, which of the cases — he liked to call them ‘his cases’ — do you feel badly about now, many years after you committed theses killings? Then I realized what I had done, and I said, ‘I understand, Henry, that you feel badly about them all now.’ And then I tried to go back and talk to him about how he felt after each killing. And he frequently would talk about the fact that he felt at peace. On the other hand, he talked about the fact that in some of these killings he could see himself committing the crime at the same time the killing or mutilation was happening. So he may have been experiencing a dissociative state.”

It’s likely that Egger will find a way to talk with more of these killers, especially those who hope to be featured in a book, because Egger is among the top-selling criminologists on serial murder.

Egger has published three books about serial murder, and his wife, Kim, has worked with him on developing an extensive database, worldwide, specific to serial killers. “I’m writing The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers for Greenwood, using my wife’s database, which she had long before we met. She’s got up to 1,500 serial killers worldwide, including between 35 and 40 variables per killer. She’s got everything from the number of victims to their sexual preference to the conviction to time frame on when they were killing.”

Together they have gathered as much as they can on each case they’ve included, although Egger admits that tracking this type of crime in some countries runs into problems, “particularly some of the cases in South America, and some material that has to be translated, such as from Ecuador and Peru.” He points out that certain cultures adopt attitudes toward serial murder similar the one the former Soviet Union used to have: It just doesn’t occur in their system. “Some occur in the Arabian countries, which they don’t admit,” Egger explains, “and we have a tremendous amount of serial killers in Russia that we’re never going to find out about. They were either executed or shuttled away to a hospital for the insane, because the USSR didn’t want to admit that they had a problem.”

The database will nevertheless prove to be a tremendous boon to investigators, criminologists, psychologists, and other researchers who hope to learn about what is and what is not consistent from one case to another, perhaps as a way to someday pinpoint certain causal factors in the development of this type of antisocial behavior.

“One of the things that is pretty consistent across the database my wife and I have done,” says Egger, “shows that a very high percentage of these people have criminal histories prior to their first kill.” He has also found a certain amount of abuse in a high percentage of cases.

In addition to this project, Egger is at work on a third edition of The Killers Among Us, as well as collaborating on a text about criminal investigation. As a leading researcher in this field, he takes a sober approach, helping to dispel myths and gather solid information for achieving greater clarity about one of our society’s most persistent dangers.

Interview with Dr. Steven A. Egger

Egger, Steven A. The Need to Kill. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003.

The Killers among Us: An Examination of Serial Murder and its Investigation.Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 1998.

Gibbons, D.C. Changing the Lawbreaker. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1965.

James, Earl. Catching Serial Killers. Lansing, MI: International Forensic Services, 1991.

Cox, Mike. The Confessions of Henry Lee Lucas, New York: Pocket, 1991.

Sullivan, Terry, and Peter Maiken. Killer Clown: The John Wayne Gacy Murders. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1983.

DeNevi, Don and John H. Campbell. Into the Minds of madmen: How the FBI Behavioral Science Unit Revolutionized Crime Investigation. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2004.

Turner, Allan and Rosanna Ruiz. “Attorneys Again Say Serial Killer is Insane,” Houston Chronicle, April 15, 2006.

Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1984.

***

With research assistance from Karen Pepper.