The Mistress of Hollywood: The Murder of June Cassandra Mincher — Death of a Madam — Crime Library

It was a hot night in Los Angeles. Around 10:30 p.m., June Cassandra Mincher descended the steps of a building the 6800 block of Sepulveda Boulevard in Van Nuys. She wore a wild print dress, tan jacket, curly black wig, and very high heels. Her good friend, Christian Pierce, accompanied her. He adored her, and as a result, he followed her at 10:30 that night into the danger zone. He had no idea that someone was watching for them.

They had just left the apartment of a friend, where June, 29, was staying. She was a well-known figure around there, having undergone over $20,000 worth of cosmetic surgery to sculpt her face, supplement her reported 66-inch bosom, and reshape her lower torso. Some say she was a prostitute, others elevate her to a madam, but in any event, she advertised in underground porn magazines for her lucrative sex-by-phone services. Known for flamboyance, she drove a lavender Rolls Royce, wore elaborate wigs under which she often stuffed thousands of dollars, and referred to herself in print as a “sexy Black goddess.” Many erroneously thought she was not a woman at all but a transvestite, in part because many of her associates were. As long as she got customers, she didn’t care what anyone thought.

To some extent, June used phone sex to perpetuate lies — or rather, to enhance fantasies. At five-foot-seven and 245 pounds, she wasn’t exactly a Playboy centerfold type, but since she supported herself on male sexual desires she had learned to manipulate by voice alone until her clients were driven to call…and call again. But some developed an obsession, and one of them decided he needed more than just a breathy voice.

Greg Antonelli, a twenty-one year-old bodybuilder from a wealthy Beverly Hills family, used every means available to learn June’s address, although she’d persistently refused to give it. One night, hoping to be welcomed, he showed up at her door. When she saw who it was, she played coy and refused to let him in, so he grew enraged and broke down the door. To his stunned surprise, he found not the sexy goddess with luxurious curls that he’d expected from photos but an obese fraud with close-cropped hair. In disgust, he called her several vile names and walked away.

Several months thereafter, on May 3, 1984, June and Christian passed a man standing outside a dark car, with a driver inside. The man mumbled something and June spun around to run. She’d seen this man before.

Christian yelled at him, “What do you want?” and a shot cracked through the night air. Christian grabbed his stomach, falling backwards. More shots caught June in the back of her head and she collapsed to the street, instantly dead, with blood running onto her clothing and the sidewalk. Someone inside the car yelled for the shooter to hurry, but he wanted to empty his gun first. Then he kicked both victims hard before he got back into the car; it sped away from the scene, but not before people had seen it.

June’s friend heard the shots and rushed out, saw the blood-soaked forms, and called the police. She knew June had been targeted before for rough treatment, possibly with good reason, but had never believed it would result in murder.

A dispatcher directed homicide detectives and other LAPD personnel from the Scientific Investigation Division (SID) to the scene, while an ambulance arrived for the wounded man. Christian had taken one bullet, but he was still alive. He was rushed away for surgery.

Photos were snapped while SID technicians, trained for evidence collection and analysis, mapped obvious evidence at the scene, then picked up what they could, logging it in. They looked for tire tracks in the street, footprints, or other telltale signs that might help identify the perpetrator but found very little. This looked like an execution, pure and simple. Whoever had done it had accomplished a fairly efficient hit. Mincher had been shot several times in the head, the impact of which had apparently made her wig fly off. She’d died where she lay. There was little doubt she had been the target. Christian Pierce had apparently just been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

As officers questioned people who gathered around, witnesses offered a sufficient amount of detail to build a description of the perpetrator: a white male, short of six feet, and of average-to-solid build, perhaps 170-175 pounds. He’d worn jeans and a windbreaker. The dark-haired man with the olive complexion might have been in the mid-30s range. The car in which he’d arrived and departed had resembled a recent model Mustang convertible, with the body and top both a dark color, possibly blue. (The witness noticed because he’d been looking for a car like it.) There had been a driver, also dark-haired, but difficult to see. Someone offered a partial number from the license plate, 2A.

Near the scene, SID picked up the black wig, bagging it, and carefully gathered six spent shell casings, including one from under the wig. These casings would help with the forensic analysis, if they managed to acquire the weapon for comparison. Having few immediate leads, detectives set about to learn more about the victim. From her outlandish apparel, they had inkling that they were in for a complicated case, but they had no notion then that it would take several bizarre twists.

Mincher had worked in the soft-core porn industry, and could be seen in several films that Russ Meyer had produced. Apparently, she also ran a small house of prostitution in the area and had been arrested on several occasions. Pierce was both a client and a friend of hers. Mincher was considered a high risk victim, just from what she did, but additional facts would come to light that had brought danger right to her door. Before that happened, there was a surprise from the autopsy.

The deputy medical examiner had removed what she estimated to be seven badly mangled .22 caliber bullets from Mincher’s head. She counted nine wounds to the body, two of which were to the left hand (one a grazing wound and the other a through-and-through). Four bullets had penetrated the skull and lodged in the brain, creating massive tissue damage. Cause of death: multiple gunshot wounds to the head.

But SID had only picked up six spent casings. Either they’d overlooked a shell at the scene, a bystander had picked it up before they arrived, or the killer had grabbed it. They went back to check more thoroughly, but found nothing. They also asked the Latent Print Division to try to lift prints from the shells, just in case whoever had touched them had left a usable fingerprint, but no match

Given the nature of the quick-hit shooting, and the use of a .22, LAPD detectives believed that some enraged customer of June Mincher’s had put a contract on her life. The weapon of choice was consistent with those preferred by hit men, because they were easy to handle in a quick-hit situation. Mincher had been such a public figure, with such a risky lifestyle, it would have been a simple matter to gun her down and flee, and a good contract killer generally left no traceable evidence.

Despite having several witnesses, this murder was shaping up like a crime that could be difficult to solve. When detectives were able to question Christian Pierce, his memory was understandably blurred, but what he was able to say was consistent with what other witnesses had told them. He didn’t know who could have ambushed them, but he clearly recalled the weapon — a long-barreled blue steel handgun. He thought he might be able to ID the shooter.

Then investigators caught a lucky break: Mincher had filed a police report a month earlier about three muscular men who’d attacked her at home. They had broken in and beaten her.

Mincher’s roommate had witnessed this assault and was able to tell police several details: one of the three attackers was believed to have been Greg Antonelli, 21. He’d been a phone customer of June’s and over a period of months June had apparently egged him into a more intense need for her services. He’d become obsessed with her but when he’d seen her, he’d been enraged.

However, says reporter Jan Klunder in the LA Times, Mincher was “love-crazed,” and after he rejected her, she reacted by tormenting him. She would call him several times a day, she damaged his car and home with graffiti, and she took to calling members of his family. The feud boiled over when he allegedly returned to her place with two bodybuilder friends to teach her a lesson. Apparently, he thought the assault would shut her up, but she filed a report. She also continued to harass his family and damage his property. (This incident would get a different spin when police learned that the bodybuilders were actually in the employ of a private detective, not buddies of Antonelli, and that June had named him as another avenue of revenge.)

One homicide detective, Rick Jackson, says there were two sides to this story: one was that Mincher had started an all-out assault after being rejected, but the other was that she and Antonelli had actually gotten into a relationship for a little while and then the attacks began. (He might be confused about timing, in that they did have a phone relationship for several months before Antonelli came to her house.) Antonelli was as guilty as June in doing damage and using threats. He apparently called police to arrest June’s roommate, angering June and setting off a round of vengeful attacks against him.

Then she was killed.

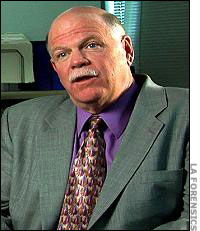

With some digging, detectives learned that Antonelli’s family had hired a private detective named Michael Pascal, an intimidating man who owned Crest Security, to learn more about Mincher’s activities and to provide protection to family members. In fact, Pascal’s crew had a reputation for aggression, even violence, and they possibly had links to organized crime. In other words, they probably would not hesitate to do whatever was asked, as long as the price was right. Sally Thomas, a Deputy DA for LA County later involved in the case, documented a check written by a member of the family for $18,000 to Pascal just before Mincher was pistol-whipped and a check for $90,000 before she was killed. Reportedly, the family had pressured Pascal to “take care of” the problem and he’d decided that his reputation was at stake, so he’d elected to ensure that Mincher never bothered the family again.

Antonelli remained a suspect, at least as an accomplice. He also owned two guns. With this information, the police were able to get a warrant for a phone tap and they learned that he’d called June a few days before, as well as the day of, the murder. Had he tried to lure her into a trap? He claimed he’d had no part in the murder.

They brought him in for questioning, and he failed to provide a solid alibi, aside from his claim that he was in another state, so he was placed under arrest. It seemed fairly clear to investigators that Antonelli, whose physical appearance fit witness reports, was their best bet. Yet he told them that the reason Pascal had been hired was because Mincher’s harassment had scared him.

Charged with murder and attempted murder, Antonelli went free on $75,000 bail. Investigators wanted to look into the backgrounds of the six bodyguards that Pascal had hired, says Michael Connelly in Crime Beat, but by the time they did, the men had left the agency and were difficult to locate. No weapon was found that could be tied to the crime.

Pascal then mentioned, says officer Rick Jackson, that he’d done his own investigation of the scene, since the family had hired him to protect them from Mincher, and he’d found a shell casing there, which he now turned over to the police. Thus, they could account for the missing casing. It proved to be a match to the others.

In June 1986, over his protests of innocence, Antonelli went to trial for the murder of June Mincher, charged as the driver of the getaway car.

Reporter Jan Klunder covered the three-week trial, describing an array of unusual witnesses: “a transsexual who performs in pornographic films, a former cocaine addict, a man with alleged ties to a notorious felon, and a woman who said she suffered a nervous breakdown eight months ago after her mother was killed by her son.”

In stark contrast, Antonelli’s wealthy family was also present in the courtroom. There were rumors that one witness had changed his story about identifying Antonelli because he hoped the family would pay him.

Deputy district attorney Andrew Diamond argued that Antonelli was driving the getaway car on the night of the shooting, but he could not at this time offer the identity of the shooter. However, Antonelli’s two defense attorneys insisted he had been living in Phoenix, Arizona, when the shooting occurred, hiding from Mincher.

More details emerged about the nature of the conflict between the victim and the defendant. They had begun a phone affair in the summer of 1983, after Antonelli had called in response to one of Mincher’s ads. At that time, she was using one of her 33 aliases, Pam Rogers. They began talking for hours a day, and Mincher apparently developed a crush on him. Antonelli, for his part, believed he was in love, said his attorney, but apparently he was in love with a fantasy image, because he could not tolerate what Mincher looked like when he saw her. “He was cruelly disappointed with the actual person he saw.”

Mincher was unable to deal with rejection, so she’d launched a campaign of terror against him, his father, his grandmother, and others in his family. In some calls, they’d alleged to police, she had threatened to have Antonelli killed. “Telephone records showed that as many as 72 calls in 45 minutes were made from Mincher’s apartment to the Antonelli family,” states Klunder. “Hundreds of phone calls were made almost daily.” June apparently enlisted some of her friends to help her keep up the disturbing barrage. “Inexplicably, the records also showed several calls to the Vatican.”

But the feud was not one-sided. Among Mincher’s friends was a transsexual named Robin. She claimed that she listened in on conversations between Mincher and Antonelli and had heard him threaten to kill her if she didn’t leave him alone. Robin agreed that Mincher was obsessed with him and was calling continuously.

Mincher was the primary suspect in a fire-bombing that had damaged Antonelli’s car in November, as well as in an arson incident at his father’s store. She also sent Antonelli photos of himself which he’d once sent to her when he thought he loved her, but she’d mutilated them by carving out the heads. She’d filled the return envelopes with rose petals.

That’s when Michael Pascal’s security company was hired and Antonelli’s father sent Antonelli to live in Phoenix. The police apparently could not locate Mincher for questioning at that time. Yet if Antonelli had truly been so afraid, why had he made two calls to Mincher from Phoenix? His defense attorneys did not explain.

Two separate witnesses, including Pierce, identified Antonelli as the driver of the getaway car, and while the attorneys disputed this, they could not prove that Antonelli did not fly to LA for the evening of the incident and then fly back. They could only say he was with a girlfriend in Phoenix. However, the prosecutors were speculating as well; they had no records to prove their version, only witnesses. Pierce, not the best witness, claimed that he’d seen a man who looked like Antonelli in a car outside Mincher’s apartment just before they were shot, and that he was talking to another man who resembled the shooter. However, he’d earlier said he could not identify the driver.

Despite the apparently solid circumstantial case against Antonelli, along with a credible motive, things fell apart. One witness had said he was no longer so certain about his identification because he’d been using cocaine, and SID had been unable to link the shell casings from the scene to either of Antonelli’s guns. The prosecutor had nothing else to offer, and the jury decided the case against Antonelli was not convincing.

He was acquitted. By court order, the bullet casings were destroyed.

The murder of June Mincher was now officially unsolved and soon it grew cold. Nearly a year passed after the trial before another lead raised the possibility of a new suspect.

The Mincher case would soon be linked to an even colder case, but one that was being actively investigated, because it had been a celebrity hot potato. The Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department contacted the LAPD to compare notes. Michael Pascal, it turned out, was a name common to two murders. So were the names of a few of his bodyguards.

Roy Alexander Radin, a movie producer from New York who’d staged successful vaudeville revivals, was working with other Hollywood notables on putting together deals to back the expensive production of The Cotton Club. The story was based on a famous nightclub in New York City that had operated throughout Prohibition. Opened in 1920, a gangster took over operations three years later, offering bootlegged liquor, scantily-clad female dancers, and even strippers. Francis Ford Coppola directed the 1984 film which starred Richard Gere, Diane Lane, and Gregory Hines. While it did not do well at the box office, the film was nominated for several awards, including Golden Globes for Best Director and Best Picture (Drama) and the Oscar for best Film Editing.

But Radin never saw it get produced; on May 13, 1983, he went missing. A month later, in a wilderness area outside Gorman, California, a man was searching for a canyon in which to place a beehive for his honey business. According to author Steve Wick in Bad Company, on June 10, he drove with a female ranger into Caswell Canyon. Since it was a hot day, it didn’t take long for him to smell the odor of decomposition near the spot they’d selected. The man walked around a bush and saw a human hand sticking up in the air, then the shape of a business suit, and a hunk of hair. “One side of the face was mostly gone, leaving a portion of the skull on top and the jaw line at the bottom.” Whoever it was, he’d been there a while.

Sheriff’s deputies arrived to rope off the scene and look for physical evidence. Spent bullet casings were found in piles, along with beer cans and broken bottles, as if this were a shooting range. Missing person reports were checked, and the suit was matched against a description of the one that Radin had been wearing the night he climbed into a limo and never came back.

After the remains were removed for an autopsy, investigators returned with a filtering screen to sift the soil for evidence or more remains. Six or seven feet from where the body was found they picked up a jawbone that held several teeth. This, too, helped to establish that the remains were those of Radin, via dental records, as did his fingerprints.

Detectives believed the Radin murder had been a contract hit and surmised that his face might have been destroyed with a bomb or shotgun blast. Given the sensational nature of this crime and the intense degree of media exposure, the police searched frantically for witnesses and leads, but no one came forward. It seemed that people were afraid of whoever had shot Radin, and if it had been a contract hit, then such a killer would not hesitate to kill witnesses, even accomplices.

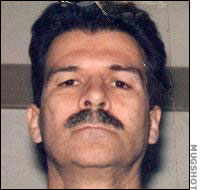

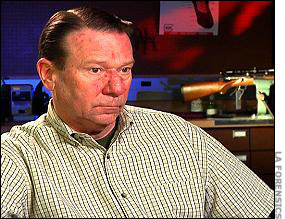

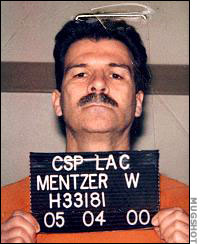

A man name William Mentzer came under suspicion after an anonymous informant called in a tip on Mentzer’s association with a drug deal. An arrest resulted in a warrant to search his apartment. Among the items of interest were photographs of Mentzer standing with two other men in an area that resembled the very place where Radin’s corpse had been dumped. (Sergeant Carlos Avila even drove back to the place with the photo to confirm it.) But they could not identify either of the men.

Mentzer beat the rap on the drug charges, so the case went cold.

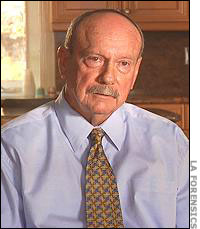

In early 1987, LA County Sheriff’s deputies, Sergeant Bill Stoner and Detective Charlie Guenther, on a cold case assignment, looked over the documents from the Radin case and saw the picture. By this time, Mentzer had gotten a divorce — the type of development cold case investigators count on.

“Detectives have solved scores of cold cases,” says Dr. Richard H. Walton in Evidence Technology Magazine, “by exploiting two primary solvability factors: changes in relationships and changes in technology.” Sometimes former spouses are angry and want to talk, or might at least provide more information than they had previously. Perhaps they’ve grown less afraid, become religious, or distanced themselves from the crowd with which they once ran. In any event, people close to a crime often loosen up as years pass.

In this case, Mentzer’s ex-wife was able to identify and provide information about the two men in the photos. One, whom she believed to be aggressive and dangerous, was Alex Marti. The other, she said, was Bill Rider. She viewed him as a gentleman, very professional. He was even a former cop, and he’d been part of a security firm that had once employed Mentzer. That was good news for the investigators.

Rider had moved out of state, they learned, and when he was asked to return to Los Angeles for an interview, he resisted. He said he had a family now and did not wish to put himself or them into harm’s way. Rider knew that Mentzer was dangerous because he’d heard Mentzer and his cronies make claims about murder. If he participated, he’d have to have a lot of security.

After a few months of discussions, Rider agreed to be flown back to Los Angeles to tell the detectives what he knew. He’d been a cop once, after all. As long as they assured him protection, he would do what he could, although he insisted he would not testify. His cooperation proved to be the break the detectives needed…in both cases.

Bill Rider was brother-in-law to Larry Flynt, publisher of Hustler magazine, and had become head of his security force. Rider had friends, who worked out at Gold’s Gym, whom he often hired for jobs on the Flynt estate in Bel Air. Among them was William Mentzer, a bodybuilder who often worked as security guard — and more. He could also be hired to intimidate people into paying their debts. Rider also hired Alex Marti and Bob Lowe. They all struck him as pretty tough. Marti, only 22, seemed especially dangerous.

In a 1997 court document, the story is fully spelled out. Rider said that Alex Marti, Bob Lowe, and Bill Mentzer had all made statements to him in 1983 that implicated them in the murder of Roy Radin. He was alone with Mentzer one day at the Flynt estate when Mentzer mentioned he’d recently done “a hit” and had dumped the body in an area known to them both, Caswell Canyon. They’d used it for target practice. Mentzer apparently bragged that he’d committed the perfect murder because it had happened four months earlier and he’d not been caught.

Subsequently, Rider was alone with Marti at this same estate when Marti, too, admitted to participating in the hit. He even said that he’d taken the first shot at “Rodan” while Mentzer shot second, and only after he’d had a “pint of wine” to prepare himself. Marti thought Mentzer had been “chickenshit” about the job. Marti, apparently, had enjoyed it; he reportedly went a little crazy and just kept shooting well beyond what was needed to kill the man. (They had been ordered to destroy his face so he could not be identified, if found.)

Mentzer and Marti together showed Rider the newspaper article about the discovery of Radin’s body, and news reports that Mentzer had recorded (apparently enjoying the infamy). It was indeed near the site where they had gone shooting targets. Marti even offered to sell to Rider Radin’s Rolex watch and a ring he’d taken from the dead man’s hand.

Mentzer believed the job was untraceable because he’d used hollow point bullets, which, because of the hollow cavity in the nose, expand when they enter a body and obtain a caliber greater than their actual size. They also break into pieces. However, he apparently did not realize that such bullets can still be traced to a specific firearm via the shells.

Rider asked who had paid for the hits and was told it was a woman named Laney Jacobs. Mentzer said Laney had wanted to punish Radin for a cocaine theft and for cutting her out of an important Hollywood deal. She had given all the directives.

After leaving the job with Flynt, Rider ended up working again in Texas with Bob Lowe, and it was then that he learned about yet another killing. Lowe had been the driver for this one and he described how he’d yelled at Mentzer to get back in the car after Mentzer did the hit. Mentzer had shot another victim as well, although that one —a man— had survived. Rider recalled Mentzer borrowing his .22 Stern Ruger semiautomatic pistol, equipped with a sound suppressor, around that time for a job for Pascal and realized that this had been the job. Mentzer had returned it a couple of months later.

Upon hearing about these conversations, the detectives realized that Rider was giving them the solution to two of their more notorious cold case killings. But they had a problem: no corroborating evidence.

They asked Rider what he could do to prove that Mentzer was responsible for Radin’s demise and he said he still had the gun that Mentzer had used. He turned it over so the Firearms Identification technicians could run some tests. At this point, one officer from LAPD’s Cold Case Unit, Rick Jackson, and one from the LA Sheriff’s Department, Bill Stoner, began to work together. They had an informant common to both cases, as well as at least one suspect, if not more.

“When we went through the files,” says Stoner, “we realized that back in 1984 the original investigators had run Mentzer’s name in the state computer system…and realized that he had been named as a possible suspect Radin’s killing. That case was being handled by the LAPD and the original investigators…started comparing their notes to see if there was anything they could use to build a double case against Mentzer.”

They worked so well together on these parallel investigations they became like partners.

SID had some bad news. They were unable to make a comparison between bullet casings fired from Rider’s gun and the casings picked up at the scene of Mincher’s murder. Apparently when Antonelli was acquitted, the casings had been destroyed. so there was no longer any physical evidence that could definitively tie Mentzer to the scene. For the detectives, this news was disheartening.

But there was one piece of evidence that offered a shred of hope.

In 1983, no one had thought to examine June Mincher’s wig. It just seemed like something that had flown off her head from the impact of the multiple shootings. Then Pascal had offered the “missing” shell, so there had no reason to keep looking for it.

But there was nowhere else to turn, so SID took the victim’s wig out of the evidence and room and examined it. They went over it, tress by tress, probing the bloody areas where the initial bullets had impacted the skull before the wig flew off. Then one technician felt something odd — a small, hard lump. He worked it though the matted hair with his gloved fingers until he was able to identify it. To his surprise, it was a shell casing from a .22. Apparently, this was the seventh casing that no one had found. It had been tangled in the wig. Pascal, associated with Mentzer, must have shot another bullet from the murder weapon and presented it as a shell from the scene, in order to make the police think they had all the evidence.

This was a great relief to everyone involved. Now they had a way to use a ballistics analysis to try to confirm a match. Edward Robertson, the firearms examiner assigned, shot four or five test bullets with Rider’s weapon. Those who were waiting for the results could only hope that the quality of the mark on the recovered shell would be sufficient to make a solid comparison.

Matching an ejected casing to a gun means shooting the suspect gun (if recovered) in the lab’s firing range. Then a comparison can be done between the shell casing from the scene and the one the examiner shot. People sometimes mix different brands of ammunition, so it’s necessary to use the brand under investigation. Since the test bullet must be recovered, the gun is fired either into a tank of water for very soft metals or into thick cotton batting for others. Then it’s compared for similarity of microscopic scratches. At least two bullets should be fired for test purposes, says Robertson, to ensure that the firearm is producing individual characteristics. They’re compared in the same way that a test-fired casing is compared to the evidence casing.

On a comparison microscope, views of the casings are linked optically. It takes skill and experience to make a definitive match, but it’s possible to say that a certain bullet came from a certain gun, and only that gun.

“A firearm in the area of the breach,” Robertson said, “is generally made of steel and the cartridge case is made out of brass. So the chamber portion of the barrel, the firing pin, extractor, or any metal part that comes in contact with that cartridge case can lead to the tool mark that can be identified back to the specific area of the firearm.” He would then set the casings on a comparison microscope and do an analysis. If the shells from the scene are marked in the same area as the test-fired shells, then he could advance further to look at finer indicators on the shells that make the tool marks distinct and individual. “It’s a matter of pattern recognition.”

Criminalist Richard Marouka with the LAPD Firearms Identification Division adds that bullets are weighed as well, to help determine their physical characteristics. “The lands and grooves can be optically measured and those measurements can be cross-referenced to a book we maintain in our laboratory that will denote specific types of firearms that could have fired those bullets. No two fired cartridge cases from two different firearms will be exactly the same.”

In 1984, he says, there were no digitalized databases, as there are today, for computerized comparisons. It fell to an experienced examiner to make the identification. “A qualified analyst,” says Marouka, “has the ability to say with one hundred percent certainty that if a fired cartridge case was fired in a specific firearm, based upon its individual markings, it was.”

If the gun is not recovered, there’s another approach.

It’s possible tell something about the make of a gun from the type of cartridge case or bullet found. The direction of twist refers to the way the rifling gives a right or left-handed spin to the bullet when fired. Smith & Wesson guns have five lands that twist to the right, for example, and a Colt .32-caliber revolver has six that twist to the left. To get this determination, the analysts point the casing away and examine how the lines of striation angle from base to nose, and they add up the number of marks around it. To say that two bullets are from the same gun, the land impressions must match both in number and on the angle of twist.

So, SID fired Rider’s handgun and then compared the shell casing against the casing from the wig. The markings were a match. In addition, the magazine capacity of this gun, which accommodate nine rounds (with one more in the chamber), meant this gun could have fired one shot at Pierce and seven at Mincher. Rider’s gun had been used to shoot June Mincher, and Rider’s recollection had put that gun into Mentzer’s hand.

“It gives you the momentum for the next group of things that you feel you have to do,” Rick Jackson stated, “to tighten up the case.”

There was additional evidence as well, albeit circumstantial. Mentzer had rented a blue Mustang convertible on the day of Mincher’s murder, and witnesses still around identified it as similar to the car they had seen. The implication was that Pascal, in taking his orders for protection too far, had hired Mentzer to make the hit.

One final issue to resolve was the eyewitness identifications. Some had identified Antonelli, but Antonelli looked similar in body shape, as well as in skin and hair color, to Mentzer. The witnesses looked at Mentzer’s mugshot and decided they could have been mistaken about Antonelli.

The next step was to get Mentzer’s admission on tape, along with that of others who had been involved. Lowe had been part of both crimes, and Marti an accomplice on the Radin murder. And then, there was Laney Jacobs. The case had grown complex.

Rider agreed to participate in a set-up, for which he was paid a fee and given intense security. It took several months of meetings with his former associates, but finally he wore a body wire and got three of them to talk.

On May 10, he met with Lowe and recorded a conversation in which, according to court records, Lowe described how he’d been with Mentzer on a hit and had watched him get drunk first. Rider brought up Radin’s name and Lowe said, “I didn’t even do anything.” But he was aware that “someone” was shot 13 times because it had been on Friday the 13th. Lowe admitted he’d been the driver and the victim had been abducted by limo.

Detectives rented a room at a Holiday Inn, installing devices to record any conversation that occurred and setting up their operations in an adjacent room. Rider invited Mentzer here on July 7 and easily got him to describe more of the details. Rider mentioned “the fat guy” and Mentzer seemed to know he was referring to Radin. To get Mentzer riled up, Rider used Lowe’s statement about Mentzer having to be drunk to get the nerve. Mentzer was predictably incensed. He then described the incident from his own point of view.

He and Marti, he said, had been in the back of the limousine with Radin, on Sunset Boulevard. Lowe was driving. Behind them they heard police sirens and were suddenly surrounded. They panicked. Mentzer stuck the barrel of his gun in Radin’s mouth and commanded him to say nothing. Marti was on the floor, his gun pointed at Radin’s crotch. The police cars went sailing by them, on another call. Relieved, they took Radin out to Caswell Canyon to finish him off.

He also talked about the murder of June Mincher, although he did not name her. Pascal had hired him to help protect a wealthy family and the target had been a black transvestite he referred to as “the thing.” He said he’d initially rigged her car with a bomb that failed to explode and had been a member of the team that had beaten her up. When that had failed, he’d been ordered to take care of her.

“I understand you used my gun,” Rider said.

“Yeah,” Mentzer admitted, “I used your gun.”

Jacobs

The detectives had it all on tape. It seemed that their case was made, for both murders, and with several offenders. “The most important evidence that came out of our wire tap,” said Stoner, “was he started bragging about how he and others broke into the victim’s [Mincher’s] apartment and pistol-whipped her. Then he had tracked her down to where she was staying and he shot her friend first and then proceeded to shoot her several times in the back of the head.”

Warrants were issued for the arrests of Marti, Lowe, and Mentzer. But there was more to be learned, because they still did not know much about the person who allegedly had ordered Radin to be killed: Laney Jacobs. She had once been a cocaine dealer and after Radin had died, the police had gone to question her but she’d left town. Now there was compelling reason to find her.

It turned out she’d gotten married and her name was now Karen Greenberger. Her new husband had just committed suicide — although several people believed she’d shot him for his considerable fortune. “Laney” was brought in for questioning in the Radin homicide. With all the other arrests, the story was pieced together and came out in the 1991 trial. All four defendants — Jacobs-Greenberger, Mentzer, Marti, and Lowe — were tried together and the proceedings lasted more than a year.

and Karen Greenberger (right, facing camera)

Each of the defendants had two attorneys, and because of the Hollywood angle, the courtroom became something of a circus atmosphere. The defendants were prepared to try to prove that Rider was not a credible witness and to offer alibis for their whereabouts on the night of the Radin murder, or to argue that their intentions or statements had been misunderstood. The prosecution’s argument was that Jacobs-Greenberger had hired Mentzer, Lowe, and Marti to kill Radin, based on the following facts and circumstances.

Roy Radin had been involved in New York’s entertainment business, which was going under for him, and he wanted to be involved in the production of The Cotton Club. He’d met cocaine dealer Karen DeLayne “Laney” Jacobs in January 1983, and she introduced him to an important producer that April. She expected to be paid a finder’s fee should a deal go through, and to be allowed some participation in the film’s profits. (Apparently she wanted to use her part to help a drug lord with whom she was involved launder money.) Radin did not agree to the terms. He wanted nothing more to do with Laney, finding her to be a difficult woman with a lot of problems. (She was known to be paranoid and to fly into temper tantrums.)

This upset Laney, so she confronted Radin to try to persuade him to change his mind. He didn’t budge. Reportedly, she was furious. Shortly afterward, her house was robbed of $275,000 and a substantial amount of cocaine. She knew who had done it — one of her associates who had installed her security system — and she was nearly insane from stress. She accused Radin of having some part in it. He immediately put distance between himself and her, because it was clear to him she was out of control.

She hired Bill Mentzer to investigate the incident, knowing he wouldn’t hesitate to teach the thief a lesson for the right price. He referred her to Michael Pascal, who owned a private investigation agency. As Laney came to rely on Mentzer, and even to date him, she involved him in her growing need to punish Radin. She wanted to kill the man. She persuaded Radin to meet her for dinner to “talk things over,” but she had another type of evening planned for him altogether.

Mentzer enlisted four other men to assist: one would drive the limousine, one would help Mentzer control and kill Radin, and two others would take care of Radin’s assistant. (The assistant, smelling a rat, did not accompany Radin that night, thereby avoiding the planned attack.)

It was indeed Friday the 13th when Radin died. Laney had instructed Mentzer to rent a limousine and then to follow her when she and Radin got in. Then she would pop out and they could take care of the rest. So Mentzer drove her to Radin’s hotel, the Regency, around 7:30 that evening to pick Radin up. Although everyone in Radin’s circle warned him not go, he figured he could keep Laney under control, so he got into the limo.

But they never showed up at the restaurant, according to a friend of Radin’s, an actor who had tried to tail them at Radin’s request. Radin was taken to Caswell Canyon, where Marti reportedly went crazy and shot him 27 times (or 11 or 13, depending on how the story was related). Mentzer shot him once, for good measure. They stole his watch and ring, and left his body for the animals.

Lowe cleaned the limousine thoroughly before returning it, and the guns they’d used were later wrapped up and dumped in a lake. That’s why, when Pascal asked Mentzer the following year to “take care of” June Mincher, Mentzer had borrowed Rider’s Ruger. Had he been a little more careful, neither case would have been solved.

In July, Bill Mentzer was convicted of the first-degree murder of Roy Radin. Facing a second trial later that year and the possibility of a death sentence, he confessed on December 6, 1991, to the murder of June Mincher. In exchange for his confession and testimony against Lowe and Pascal, he received life in prison. He said he’d received $25,000 to kill June Mincher, and that Pascal had told him the Antonelli family did not know it was going to happen.

Laney Jacobs-Greenberger was convicted of kidnapping and second-degree murder, and was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. The judge rejected her claim, according to the New York Times, that she had only ordered a kidnapping for the purposes of extortion and never expected Radin to be killed.

Alex Marti was convicted of first-degree murder and received life in prison without parole. Lowe was convicted of second-degree murder and aggravated kidnapping resulting in death. He received life in prison without parole.

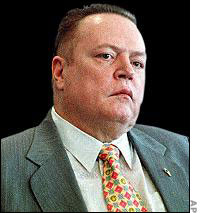

Michael Pascal, a paranoid man with wild fantasies about being followed, was arrested in 1993 and arraigned for the Mincher murder. “When we arrested Pascal,” recalls Rick Jackson, “he was shaking like a scared child.” Confused as to how the police had tied the incidents to him, he pled guilty to voluntary manslaughter. Before going to prison, he died from cancer.

Christian Pierce, too, died in 1993, from a drug overdose. At the trial, he had recognized Mentzer as the man who had shot him.

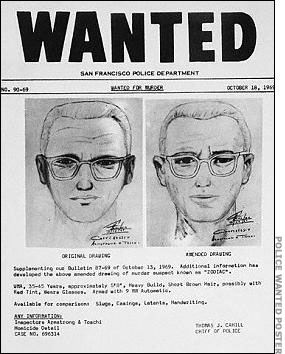

In 2004, Mentzer was suggested as a suspect in the long-unsolved series of Zodiac murders in 1968-69 in the San Francisco area. Zodiac theorists pointed out that that he’d been discharged from Vietnam in 1968, three months before the first of the Vallejo killings, and had gone to California. Apparently, he suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder for a while. His circumstances and personality fit a police profile devised at the time, but there was no actual evidence to tie him to the murders.

Given his participation in the contract murders and his apparent need to brag about them, it’s unlikely he’d have kept closed-mouthed about pulling off the sensational Zodiac killings. He doesn’t really fit the profile.

Connelly, Michael. Crime Beat: A Decade of Covering Cops and Killers, New York: Little Brown & Co., 2004.

“Slaying Case Takes a New Twist with Security Firm owner’s Arrest Crime: A. Michael Pascal is Charged with Arranging the 1984 Killing of a Prostitute in Van Nuys.” The Los Angeles Times, Nov. 17, 1991.

Klunder, Jan. “Obsession: Prostitute’s Murder Kindles Bizarre Testimony of Vendetta and Revenge,” The Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1986.

Lee, Henry C and Howard A. Harris. Physical Evidence in Forensic Science. Tucson, AZ: Lawyers & Judges Publishing Company, 2000.

“Life Term for Woman in Producer’s Killing,” The New York Times, February 12, 1992.

“New Suspect in Zodiac Murders,” New York Post, January 26, 2004.

People v. Greenberger (1997) 58 CA4th 298

Walton, Richard W. “Evidence Issues in Cold-case Homicide Investigation,” Evidence Technology Magazine, May-June 2007.

Wick, Steve. Bad Company: Drugs, Hollywood, and the Cotton Club Murder, New York: St. martin’s Press, 1991