All about the John Hinckley case, by Denise Noe — “Dutch” — Crime Library

The 40th president of the United States was a handsome actor-turned-politician named Ronald Wilson Reagan. He was elected to office when he was 69 as the oldest man to become president, but he gave off an aura of robust good health.

Nicknamed “Dutch” as a child, Reagan became a movie actor as an adult. His characters were generally sympathetic and wholesome. He played Western heroes in Santa Fe Trail (1940) and Tennessee’s Partner (1955), and military men in films like International Squadron (1941). He played the famous college football star George (the Gipper) Gipp in Knute Rockne — All American (1940). His finest role may have been as a man whose legs have been unnecessarily amputated in King’s Row (1941). A line he spoke in that movie — “Where’s the rest of me?” — became the wry title of his autobiography.

Reagan served several terms as president of the Screen Actors Guild in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He used his office to try to root Communist influence out of the film industry.

In 1940, Reagan married actress Jane Wyman. They had a daughter Maureen and adopted a boy named Michael. The couple divorced in 1948.

Reagan was remarried, to actress Nancy Davis, in 1952. Together, they had two children, Patricia and Ronald.

A Democrat until the 1950s, Reagan became more conservative and then a Republican in 1962. He won his first public office in 1966 when he was elected governor of California. He had campaigned on a platform of lower taxes and government spending and worked to slash the welfare rolls. Some critics found his manner of cutting spending mean-spirited because it targeted the poor. But even more supported the cuts. America is a country with a strong work ethic and spirit of self-responsibility. Economic failure is not regarded with much sympathy in a country that prides itself on being the land of opportunity.

Reagan remained popular even after he sponsored tax increases. Ironically, one of his tax hikes was the largest in the state’s history. He was reelected governor in 1970 and served until 1975.

Reagan campaigned for the Republican presidential nomination in 1968 and lost. He tried again in 1976 and lost to President Gerald Ford. He went for it a third time and won in 1980, then defeated President Jimmy Carter.

As president, Reagan made economic proposals that slashed both taxes and the budget for welfare and unemployment programs. These measures were popularly called Reaganomics. Unlike the less ideologically conservative President Richard Nixon, Reagan tended to get favorable treatment even with the press that has been so often seen as having a liberal bias.

One reason for Reagan’s popularity was his appearance. He had a ruddy-cheeked open face with an easy smile and eyes that twinkled. Nixon always believed that the press loved to “kick him around” because of his conservatism, but Reagan was far more consistently right-wing and got better press than the beetle-browed, funny-nosed Nixon. Unlike the notoriously stiff Nixon, the ex-actor possessed an affable manner and a way with jokes that endeared him even to many who despised his politics. Indeed, while Nixon was often savagely attacked, even Reagan’s critics tended to make fun of him in a gentle manner, concentrating on such things as his notoriously poor memory (toward the latter part of his second administration, this may have been the result of early-stage Alzheimer’s).

In his first term, the president was scheduled to make a luncheon speech before the AFL-CIO on March 30, 1981, at a Washington, D.C., Hilton. Reagan, often called The Great Communicator, spoke to about 3,500 union delegates.

Then, accompanied by Secret Service and aides, the president walked out of the ballroom and through the lobby. He was on his way to a waiting limousine and waving at the friendly crowd of reporters and onlookers when a young man went into a shooter’s crouch, both hands on his weapon, and fired.

He got off six shots in three seconds. Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy instantly jumped in front of the president. But he sank when he caught a bullet in the belly. Another agent, Jerry Parr, grabbed the president and pushed him down behind the opened rear door of the limousine just before a bullet smashed into the vehicle’s bulletproof window.

pushed by Agent Jerry Parr (AP)

Only the sixth and last bullet found Reagan, striking his armpit and tunneling into his chest. The president felt a sharp pain but thought it was only from Parr pushing him so hard. He looked at Parr and made a feeble joke: “You sonofabitch, you broke my rib” just as the limousine raced away from the scene.

(AP)

That scene was described by James W. Clarke in On Being Mad or Merely Angry as “bedlam. Amid the hysterical screams of bystanders, wailing sirens, and shouts of Secret Service agents and police attempting to gain control of the situation, Tim McCarthy lay doubled up on the sidewalk, hands clutching the bullet wound in his stomach; a few feet away police officer Tom Delahanty writhed in agony from a neck wound; next to him lay presidential press secretary Jim Brady, the first to fall, his face flattened against the sidewalk, arms twitching incongruously at his sides, blood trickling into a storm grate from a pea-sized bullet hole over his left eye.”

A Secret Service agent overpowered the shooter, coming down on top of the overweight young man and wrestling him to the ground. The president’s attacker continued clicking on the emptied gun until his hand was disabled.

Soon newspapers filled with headlines about the shooting while the videotape was seen on TV sets in homes across America and throughout the world. Condolences streamed to the White House from across the globe.

First reports were reassuring, at least concerning Reagan. The president underwent a successful operation and would soon be able to resume his duties.

Ever jovial, Reagan relied on humor to carry him through. When his wife arrived at the hospital just as he was being readied for surgery, he whispered to her, “Honey, I forgot to duck.” Through tubes in his mouth, he rasped, “All in all, I’d rather be in Philadelphia.” Just before he lost consciousness, he said to the operating team, “Please tell me you’re Republicans.”

ing victim and sponsor

of the Brady Bill to re-

strict hand gun pur-

chases (AP)

Tom Delahanty and Tim McCarthy were expected to survive. Doctors feared Jim Brady might not be as lucky. An exploding Devastator bullet had hit his brain. It was touch and go for a long time. Finally, physicians announced that he would live but be permanently impaired. Brady was paralyzed and would be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Attention focused on the shooter. His name was John Warnock Hinckley Jr. It soon became known that he had no political motivation. Rather, he was trying to impress a woman — actress Jodie Foster.

Hinckley (AP/Wide World)

John Warnock Hinckley Jr. was born in Ardmore, Oklahoma, on May 29, 1955. He was the youngest of the three children of John W. Hinckley Sr., called “Jack,” a successful businessman who became chairman and president of the Vanderbilt Energy Corporation, and homemaker Jo Ann Moore Hinckley.

All the Hinckley children were popular when very young. While his parents feared that John was a bit shier than their other two kids, he seemed like a normal, happy boy overall. As a boy, John was not a loner nor was he constantly teased. He did not get into a lot of fights with other youngsters. The family moved to Dallas when John was only four years old. John started school, where he did well. In elementary school, John played basketball and football. He was named “Best Basketball Player” by the elementary school basketball team. The Beatles toured the United States when John was nine, and he became a dedicated fan and would remain one into adulthood.

The family was affluent but not extremely wealthy. Jack put in long hours at work, providing for his family financially but leaving the raising of the children to his wife. Jack did not express affection easily and was later to write that a hug he gave John when the latter was 25 and an attempted assassin facing a life of confinement was the first time the two had hugged since John had been a small child.

young man (AP)

When John was in the sixth grade, the family moved again. They took up residence in the suburb of Highland Park near Dallas. Their home boasted a swimming pool and a private Coke machine. In this neighborhood, John was again well liked by his classmates and an active participant in school athletics. He was so popular that he was elected president of his seventh and ninth grade classes. He also managed the school’s football team. During junior high, he became interested in music. He started playing the guitar but was too shy to play it in front of anyone, even his own family.

High school was a time of negative change for the youth. When asked about “signs of trouble” during this time, his parents, in their book, Breaking Points, recalled that “‘Absence of trouble’ was nearer the truth.” Their friends used to tell the Hinckleys how lucky they were because their son was not drinking, taking drugs, running around with a rowdy crowd or sexually active.

Instead, John withdrew. He stopped making friends and kept to himself. Losing all interest in sports, he participated in no athletic activities. He did not date. The solitary teenager spent hours in his room, strumming on his guitar and listening to music, especially the Beatles. He also collected books about the famous rock band. He was lethargic. These traits especially annoyed his father who was a man who liked to get things done.

But John’s parents seemed to think he was just another introverted teenager suffering through a normal case of adolescent angst.

There is a chicken-and-the-egg question surrounding John’s suddenly reclusive behavior, one that reflects a deeper dilemma about mental illnesses in general. Did John withdraw from other people because his thoughts were becoming increasingly strange, perhaps as the result of organic defects in his brain or imbalances in his brain chemistry? Or did his thoughts become disordered as a result of the lack of input and perspective that would usually be offered by one’s friends? Could some combination of the two have been operating?

lege yearbook photo

In 1973, the family moved again, to Evergreen, Colorado, an upper-class suburb of Denver and the new headquarters for Jack’s business. John had already graduated from high school. He left his family home for Lubbock, Texas, to attend Texas Tech for a year. After that, he left for Dallas where he moved in with his older sister, Diane, and her husband and son.

John returned to Texas Tech during the spring semester of 1975. He was assigned a black roommate. He had reportedly not been taught bigotry at home but he disliked the roommate and other blacks. He began reading literature by white supremacist groups.

He quit college in April 1976. He wanted to become a songwriter and he flew to California, hoping to break into the music business.

While there, John saw the popular movie Taxi Driver. He became obsessed with the film, watching it again and again.

Directed by Martin Scorcese, Taxi Driver stars Robert De Niro as Travis Bickle, a veteran who drives a cab in New York City. Suffering from chronic insomnia, the job driving a taxi at night gives him a view of the city that fills him with disgust and loathing.

He becomes infatuated with lovely, blond Betsy, played by Cybill Shepherd. Betsy seems to epitomize everything pure and wholesome. Inexperienced and something of a clod, Bickle invites her to an X-rated movie. Utterly turned off, she refuses to date him again and he becomes overwhelmed by loneliness.

The script for Taxi Driver, written by Paul Schrader, was partly inspired by Arthur Bremer, who attempted to assassinate governor and presidential candidate George Wallace and left Wallace disabled. Like Bickle, Bremer offended and lost a young lady he was courting when he showed her pornography.

After being rejected by Betsy, Bickle makes friends with Iris (Jodie Foster), a 12-year-old prostitute. Equally blond and lovely as Betsy, she is also worldly beyond her years yet vulnerable, a preteen exploited by grown-ups. Nursing dreams of rescuing Iris from the sleazy streets and her callous pimp, Bickle begins arming himself.

One of the most dramatic scenes demonstrating Bickle’s mental deterioration shows him in the tiny apartment that he has transformed into a garrison, repeating the words, “You talking to me? You talking to me?” while the audience sees that there is no one else present.

The disturbed man stalks a rising politician but is spotted before he can shoot the candidate. The film climaxes with Bickle killing Iris’ pimp, the manager of the sleazy hotel in which she turns tricks, and a customer. We are given to believe that, somehow, Bickle’s crazed acts of violence have been interpreted by the public as heroics and that young Iris has left prostitution and returned to her family because of the bloodbath.

(AP)

John is believed to have watched this movie at least 15 times with an increasingly strong identification with its protagonist. He also became obsessed with Jodie Foster. Oedipal feelings probably played a part in his fixation on the actress. His mother Jo Ann’s friends often called her “Jodie” (they stopped calling her that in 1981) and people have remarked that when she was young, Jo Ann Hinckley bore a pronounced resemblance to the actress.

One day, the Hinckleys received a phone call from California telling them of good news. John now had a girlfriend named Lynn Collins, he said. She was a young actress from an affluent family. A trip to the Golden State had been her parents’ college graduation gift to her.

Only after John’s arrest for shooting the president would his parents learn that Lynn Collins was a figment of his imagination. He modeled her on the character of Betsy in Taxi Driver. A psychiatrist would say that she had been invented in an attempt to manipulate his parents into sending money to him. And later, she became real to him.

John wrote his parents telling them that he had cut a professional demo of his songs at a recording studio. In his letter, he said, “I hope you’re as optimistic about things to come as I am!” In reality, John had cut no demo and made no contacts in the music business.

Unable to make a go of it in music, John claimed to be disgusted by the “phony, impersonal Hollywood scene.” He returned to Evergreen in September 1976. His parents allowed him to move back into the family home but only on the condition by his father that his mother not take care of his room for him. John easily agreed to that. A neat person, he kept himself and his surroundings clean and tidy.

He got a job as a busboy in a dinner club. He worked there for a few months, then wanted to give California another try. He returned in 1977 and was again dissatisfied. So he went back to Lubbock and Texas Tech where he changed his major from Business Administration to English. Living in an off-campus apartment, he suffered a variety of physical ailments and frequently visited the Texas Tech clinic complaining of problems with his eyes, throat and ears, as well as a persistent case of light-headedness. Lonely and floundering, John spent more and more of his time thinking about fantasies revolving around Taxi Driver and Jodie Foster.

John began collecting guns as Bickle did in Taxi Driver. He purchased his first firearm, a .38-caliber pistol, in August 1979. In September, he “founded” an organization he called the “American Front” and termed it an “alternative to the minority-kissing Republican and Democrat parties.” This new political party was “for the proud White conservative who would rather wear coats and ties instead of swastikas and sheets.” John called himself the Party’s “National Director” and drew a list of members from different states. Everything about the group was invented including the names of its supposed members.

In December of that year, he took a photograph of himself holding a gun to his head. He would later tell defense psychiatrists that he had twice played Russian Roulette. He began seeing doctors and getting tranquilizers and antidepressants. At Christmas time, John informed his parents that he was traveling to New York City. He said that he would make the round of publishers to try to interest them in a novel he had written. In reality, he stayed in his Lubbock apartment.

January 1980 saw John suffer an “anxiety attack” which led him to a doctor who tested him for dizziness. He continued loading up on firearms. He formed a company called LISTALOT that offered its customers a variety of lists. The business amassed an income of $59 with an outgo of $57.

After coming across a May 1980 issue of People that said Jodie Foster was attending Yale University, John decided to plan a trip to New Haven to meet her and “rescue” her, as Travis Bickle had rescued Iris in Taxi Driver.

In early June, John signed up for a summer session at Texas Tech. He also went to the firing range to practice shooting the weapons he had purchased and suffered trouble with his hearing as a result. He purchased Devastator bullets with exploding heads. As usual, he suffered an array of minor but troubling physical ailments including dizziness and allergies. He saw a doctor who noted John’s “flat affect throughout examination and depressive reaction” and prescribed an antidepressant.

In a letter to his sister Diane, he seemed aware of his own deterioration. “My nervous system is about shot,” he wrote. “I take heavy medication for it which doesn’t seem to do much good except make me very drowsy. By the end of the summer, I should be a bonafide basket case.” He also started taking prescribed Valium for his nerves.

August saw John back in Evergreen, Colorado, house-sitting for his parents who were traveling in Europe. He met with psychologist Darrell Benjamin. The psychologist believed his client extremely immature and recommended that he put a plan for his future into writing.

In September, when John’s parents returned from their trip, he told them that he had enrolled in a writing course at Yale. They gave him $3,600 to cover it. He believed he was embarking on the beginning of a beautiful relationship. The truth that Foster was a 19-year-old woman attending one of the most prestigious colleges in the country, rather than the 12-year-old streetwalker she played in Taxi Driver, did not deter John. In his mind she needed him as a knight and savior.

John left letters and poems in Foster’s mailbox. He was able to get her phone number and had two conversations with her in which she gave him a polite but firm brush-off.

“I can’t carry on these conversations with people I don’t know,” she told him. “It’s dangerous, and it’s just not done, and it’s not fair, and it’s rude.”

“Well, I’m not dangerous,” he told her. “I promise you that.” He tape-recorded his conversations with Foster.

In his confused mind, John came to believe he knew a way to Foster’s heart. He would assassinate a president, thus proving his own importance and imitating Travis Bickle who had intended to kill a presidential candidate. John followed Jimmy Carter around with the idea of shooting him.

(AP)

John traveled to Nashville where President Carter was scheduled to make a campaign appearance. An airport security device detected handguns in his suitcases. The firearms were confiscated. John was in custody for a few hours and paid a $62.50 fine.

An increasingly distraught John Hinckley Jr. moved back into his parents’ home in Colorado. His mother found him sick from an overdose of the antidepressant he had been prescribed, Surmontil. The parents insisted that he seek treatment from a psychiatrist. He began seeing the thin, bespectacled, balding Dr. John Hopper.

The Evergreen doctor believed John a “typical” case of social underdevelopment who simply needed to learn to stand on his own two feet. Dr. Hopper did not heed some pretty strong warning signs from his patient. On November 4, Election Day, John told Hopper about his obsession with Jodie Foster.

Unbeknown to the doctor, John also revealed a partial glimpse into that obsession in a letter to the FBI. The epistle was anonymous. It read: “There is a plot underway to abduct actress Jodie Foster from Yale University dorm in December or January. Not ransom. She’s being taken for romantic reasons. This is no joke! I don’t wish to get further involved. Act as you wish.” The head of Foster’s dorm and Foster herself were told of the threat.

John turned a three-page autobiography that the doctor had requested he write in to Hopper in November 1980. In those pages, he called the period from mid-September to mid-October “a month of unparralleled emotional exhaustion.” He further stated, “My mind was on the breaking point the whole time. A relationship I had dreamed about went absolutely nowhere. My disillusionment was complete.” He was talking about the trip he had made to Yale University where he attempted to make friends with actress Jodie Foster. Dr. Hopper did not follow up on this.

The essay also said that, “I have remained so inactive and reclusive over the past 5 years I have managed to remove myself from the real world.”

In fairness to Dr. Hopper, psychiatry is a notoriously inexact science and John was not entirely candid with the doctor who was also seeing his parents. He never told Dr. Hopper about the thoughts of violence that were increasingly prominent in his mind.

before his murder

(AP)

Along with much of the world, John suffered a major trauma on December 8, 1980, when John Lennon was shot. He took a train to New York City where he joined the Lennon vigil in Central Park. He went home by plane and Jack and Jo Ann met him at the airport. His eyes were red and he looked uncharacteristically disheveled.

“Don’t make any cracks about Lennon, Dad,” John told his father. “I’m in deep mourning.” That he would feel the need to make such a remark speaks volumes about the absence of sensitivity and communication in their relationship.

Even as John mourned Lennon, he found himself identifying with the troubled young man, Mark David Chapman, who had assassinated him. John soon bought a Charter Arms revolver like the one Chapman had used to kill the rock star.

Young Hinckley had more sessions with Hopper.

John made a tape recording on New Year’s Eve. “It’s gonna be insanity if I even make it through the first few days,” he said. “Anything that I might do in 1981 would be solely for Jodie Foster’s sake . . . I wanna make some kind of statement or something on her behalf . . . All I want her to know is that I love her. I don’t want to hurt her or anything. I can’t hurt anybody, really. I’m such a coward, really.”

He found time to practice shooting and to travel to New Haven to leave poems in Jodie Foster’s campus mailbox.

He returned to New York City, seeking young prostitutes he could “help.” They did not appear to welcome him as a rescuer but were happy to accept his money. He gave up his virginity with a teenaged prostitute and later said he had enjoyed sex with four hookers, three of whom were teenagers.

On St. Valentine’s Day, John took a cab to the Dakota apartment building, in front of which John Lennon had been murdered. John later said he intended to commit suicide there. He couldn’t do it.

Returning home, he met with Hopper on February 27, 1981. It would be their last appointment. He stole from his parents to finance another trip to New Haven. There he left notes for the actress he idolized, telling Jodie Foster, “Just wait. I’ll rescue you very soon. Please cooperate.”

Like John’s own father, Dr. Hopper believed his patient was simply a young adult emotionally stuck in adolescence. He would not shoulder adult responsibilities as long as his parents continued to bail him out of jams. Thus, the psychiatrist prescribed a kind of “Tough Love” regimen in which the Hinckleys were to simply shove this youngest child who was an adult out of the nest and leave him to fly on his own no matter what. The psychiatrist and the Hinckleys worked out a plan to get John out of the home by March 30 the day on which he shot Reagan and others.

Wavering and unsure, Jack wanted to abide by the psychiatrist’s plan. When John flew to Evergreen from New York on March 7, Jack told John he could no longer stay in his parents’ house. He drove his son to the airport. Later Jack would painfully recall that “I told him how disappointed I was in him, how he had let us down, how he had not followed the plan we had all agreed on, how he left us with no choice but not to take him back again.” He handed John a couple of hundred dollars. “You should stop at a YMCA,” Jack suggested. John said he didn’t want to. “OK, you’re on your own,” Jack replied. “Do whatever you want.”

John was on his way to New Haven, where he wanted to kill himself in front of Jodie Foster or perhaps murder her and then commit suicide, and took a bus to Washington, D.C. There he saw Reagan’s schedule for the next day in a newspaper. Then he wrote a never mailed letter to Jodie Foster. “I will admit to you that the reason I’m going ahead with this attempt now,” he began, “is because I just cannot wait any longer to impress you. I’ve got to do something now to make you understand.”

Presiding over the trial of John Hinckley, Jr. was Judge Barrington D. Parker, a black Republican who had been appointed by President Richard Nixon. Parker had a sharply receding hairline, a trim mustache, and a serious, scholarly manner. He was disabled and walked with the help of crutches.

Vincent Fuller, a short, stocky, silver-haired man, led the defense team. He was a partner in the respected, high-priced Washington law firm of Williams & Connolly. Assisting him was a tall young attorney with the memorable name, Greg Craig.

The tall, self-confident Roger Adelman, who enjoyed sporting broad ties decorated with Stars and Stripes, led the prosecution.

“The jury’s got to be well-educated,” Jack Hinckley kept saying before they were impaneled. After all, they would be going over some of the most complex medical and legal issues in existence, questions that even experts find confusing. However, he and everyone else connected with the case knew that the chances of a jury composed of people boasting advanced degrees was slim. The pool consisted of Washington, D.C., inner-city residents. They were people who were likely to start out with a grudge against a privileged child of the suburbs. Thus, John’s attorneys had to ask every prospective juror if he or she could be impartial to a defendant from an affluent suburban background. Even more embarrassingly, they had to ask prospective jurors, mostly blacks, if they could be impartial toward a person who was prejudiced against blacks.

The jury that was impaneled consisted of seven women and five men. There were 11 blacks and one white. They were working class, blue and pink collar people. The group included a janitor, two secretaries, an information-control clerk, a parking lot attendant, and a hotel banquet worker. These were the people who would decide the fate of a bigoted white from an affluent family who had been recorded on videotape shooting the president of the United States and three other people.

Many observers believed a trial was a waste of time and money. A guilty verdict seemed a foregone conclusion.

Hinckley’s family and his attorneys pinned their few hopes on one early victory. Judge Parker had ruled that the burden of proof regarding the defendant’s mental status would rest with the prosecution. Thus, the district attorney had to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that, at the time of the shooting, John Hinckley Jr. was legally sane.

In his opening, prosecutor Adelman emphasized evidence that the defendant had stalked his targets, had exercised care in choosing the exploding Devastator bullets to maximize the damage to his victims, and that four of six of his shots had hit people.

The defense opening did not dispute the facts mentioned by Adelman but asserted that they were the actions of a person who could not be held fully responsible because his mind was so unhinged.

The government’s case started with two powerful videotapes. The courtroom was darkened while six TV sets displayed a crowd on a campaign stop that then-President Jimmy Carter had made in Dayton, Ohio, in 1980. The action was stopped. A pointer was directed at a small face in the background of the screen: that of John Hinckley, Jr.

Then the tape of the terrible events of March 30, 1981, a tape that had been seen innumerable times in TV sets in homes all across America, was played. The jury saw, as they had to have seen as private citizens before, John take aim at President Reagan. They heard the panicked cries of “President Reagan, President Reagan!” as well as the six pops almost masked by the noise of big city traffic.

Two of those John shot, police officer Thomas Delahanty and Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy, took the witness stand. The jury was shown photos of all four victims and articles of clothing that still bore bloodstains. A neurosurgeon from George Washington University Hospital testified about how James Brady’s brain had been damaged by the shooting.

Ballistics experts identified the gun that John had used. They showed the bullets recovered from the victims. A FBI agent read from a postcard that John had written to Jodie Foster but never mailed. “Dear Jodie,” it read, “one day you and I will occupy the White House and the peasants will drool with envy.”

The evidence and testimony were powerful and moving. John had done incalculable harm. Brady was permanently disabled by the defendant’s bullet.

After the prosecution rested its opening case, the defense began.

Jr. (AP)

Chubby John Hinckley Jr. sat in court without much expression on his face. There was a haunted look about the heavy-lidded eyes, a sort of permanent anxiety pinching at the eyebrows but no tears, no hysteria, no obvious remorse or shame.

The defense called Dr. John Hopper to the stand. He was not called as a medical witness as other psychiatrists would be but as a witness to facts. Dr. Hopper testified for seven hours. He seemed understandably embarrassed for he had to tell the world about the failure of his diagnosis and the obvious destructiveness of his prescribed treatment.

Dr. Hopper said on the witness stand that he and others did not demonstrate “as much concern as we all realize now that we should have.”

Perhaps the most pitiful witness was Jack Hinckley Sr. Balding and gray, Hinckley was a successful man used to having his own way. Now he had to explain before a world of strangers how he had failed his son and namesake.

He testified that following the doctor’s orders and expelling his adult child from his home had been the “greatest mistake” he had ever made. He told how his son had flown back to Denver from New York on March 7. “On the way to the airport, I prayed that we were doing the right thing,” the father recalled. “His mother couldn’t go with me. She couldn’t bring herself to do it. . . [John Jr.] was dazed, wiped out. He could hardly walk from the plane.” He told the court how he had remonstrated with his son, then told the young man that he was on his own.

When remembering this, Jack choked up. “I am the cause of John’s tragedy,” he said as tears blurred his eyes. “We forced him out at a time when he just couldn’t cope. I wish to God that I could trade places with him right now.” He took out a handkerchief and wept into it as his wife, also crying, left the courtroom.

John stared stoically ahead.

Moving as Jack’s testimony was, he was vulnerable on cross-examination. No, he had to answer, he had never heard his son say anything about “voices in his head.” He could not testify to the most classic symptoms of schizophrenia.

While John showed little emotion during the testimony of his father, he showed quite a bit of passion when a videotape of Jodie Foster testifying was played.

That tape had previously been made during a special closed session to protect Foster’s privacy. However, John had been in court during that session.

The young, blond actress answered questions calmly, occasionally brushing her hair out of her face with her fingers.

“Did there come a time shortly after you started school at Yale,” Craig Greg asked, “when you received certain written communications from John W. Hinckley, Jr.?”

“Yes,” Foster replied. “That is correct.”

“Did you ever see the person who delivered the communications to your mailbox or beneath your door?”

“No, I did not.”

“Did any of your roommates to your knowledge ever see the person?” Greg inquired.

“No, I don’t think so.” She went on to relate that the first letters from John were lovelorn fan mail of a sort she often received. She got a group of them in September 1980 and a “second batch” in October or November of that year. She threw them away. Then the tone changed in the notes delivered by him in early March 1981. “The third batch was a different type of letter,” she explained, “so I gave it to the dean of my college.” Her concern was warranted. One letter from that group said that, “after tonight John Lennon and I will have a lot in common. It’s all for you, Foster.” Another said, “Jodie Foster, love, just wait. I will rescue you very soon. Please cooperate. J.W.H.”

“Have you ever seen a message like that before?” Greg asked.

“Yes, in the movie Taxi Driver the character Travis Bickle sends the character Iris a rescue letter,” Foster replied.

Later, Greg inquired, “Now, with respect to the individual, John. W. Hinckley, looking at him today in the courtroom, do you ever recall seeing him in person before today?”

“No.”

“Did you ever respond to his letters?”

“No, I did not.”

“Did you ever do anything to invite his approaches?” Greg asked.

“No.”

“How would you describe your relationship with John Hinckley?”

“I don’t have any relationship with John Hinckley,” the actress said.

When Foster first spoke those words in John’s presence, he flung a ballpoint pen at her and shrieked, “I’ll get you, Foster!” Marshals rushed him out of the room.

When the tape was played in the courtroom, an agitated John jumped to his feet, his arm up as if he were trying to ward off the words from the screen like one would ward off blows. He raced for the door, the marshals running after him.

Although John Hinckley appeared indifferent to people, like his parents, that he should have been intimate with in real life, he could be aroused to fury and shame by a stranger.

court (AP)

Psychiatrist William Carpenter of the University of Maryland was convinced that John was delusional. A tall, well-groomed man with a silvery beard and shoulder-length hair, he was a strong witness for the defense. He told the court that young John had begun a descent into “process” schizophrenia when he was a lonely, isolated teenager. This type of schizophrenic has a blurred sense of identity. Because a sense of self is unformed, they often try to assume bits and pieces of the identities of characters in books and films. Thus, John compulsively imitated {Taxi Driver’s} Travis Bickle, wearing the kind of clothes he wore, buying the same kind of guns, and even drinking peach brandy because that was the sort favored by the character.

There were several major attributes that John possessed that pointed to a diagnosis of schizophrenia, Dr. Carpenter told the court. One was “blunted affect” or “an incapacity to have an ordinary emotional arousal that should be associated with events in life.” Another was his “autistic retreat from reality.” He also showed severe impairment in lacking friends and being unable to work.

(AP)

Dr. Carpenter told the court how, after Foster’s refusal to meet with him, John withdrew even more into the world of his fantasies. The court heard how John had flown to New York City trying to find a prostitute similar to Foster’s character whom he could “rescue.” Then he got the idea of impressing her with violence. Despite his own grief, John was strangely encouraged by the murder of John Lennon by Mark David Chapman. Around the time of that slaying, John wrote, “Inside this mind of mind I commit first-page murder. I think of words that would alter history . . . This mind of mind doesn’t mind much of anything unless it comes to mind that I’m out of my mind.”

The psychiatrist testified that when John’s parents followed Dr. Hopper’s orders and threw him out, their son lost “his last important links with the real world.” He put down “J. Travis” as his name when he registered in a Denver motel. He obsessively considered various things that would supposedly bring him and Foster together. For awhile, he considered committing a mass murder at Yale where Foster was going to college. Then again, he might hijack a plane. The actress would be the ransom. Thoughts of suicide also recurred.

Then he came across Reagan’s itinerary. Hinckley’s illness also manifested itself in the way he interpreted events as being somehow done specifically for him. “There had been a series of Jodie Foster films on TV in a short period of time,” Dr. Carpenter said, “that he had sensed that they had been put there in some personal way in relationship to him . . . He had that same kind of highly personalized sense of when the president presumably waved and smiled to a crowd of people” and Hinckley believed Reagan was looking directly at him.

Dr. Carpenter said that he thought that John had a “substantial lack of capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct on March 30.” On a “purely intellectual level,” Dr. Carpenter allowed, the accused knew what he was doing was illegal. “Emotionally he could give no weight to that,” the doctor said, because he was “dominated by the inner state by the inner drives that he was trying to accomplish in terms of the ending of his own life and in terms of the culminating relationship with Jodie Foster.”

The prosecution contended that, while certainly emotionally disturbed, John was not disturbed enough to escape responsibility for his March 30 actions. The government’s doctors made a report on Hinckley’s mental state that was never entered into evidence (it was 628 pages long) but upon which the prosecution psychiatrists drew in their testimony.

Dr. Park Dietz, 33, led the government’s team of psychiatrists. He and the other government doctors had found that John suffered from three different types of personality disorder: schizoid, narcissistic and mixed. His mixed personality disorder had both borderline and passive-aggressive features. He also suffered “dysthymic disorder” which may be understood as a mood of persistent sadness.

The report itself noted, among many other things that the defendant had “a pattern of unstable interpersonal relationships; an identity disturbance manifested by uncertainty about several issues relating to identity, namely self-image and career choice; and chronic feelings of emptiness or boredom; features of passive-aggressive personality disorder include resistance to parental demands for adequate performance for occupational and social functioning, combined with dawdling . . . inability to sustain consistent work behavior . . . lack of self-confidence. . . “

According to Lincoln Caplan in The Insanity Defense and The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr., “some reporters at the trial dubbed these traits ‘dementia suburbia.'”

None of his problems, Dr. Dietz firmly told the court, made him legally irresponsible. As Caplan wrote, “seen through Dietz’s eyes, Hinckley became a lazy, fame-seeking, manipulative, self-concerned, and privileged loner, who harassed his parents about his inheritance, lied to them and tricked them out of money.” He had not held a job for very long, Dr. Dietz indicated, because he simply disliked working.

“The desire not to work can be traced back at least to the time after Mr. Hinckley’s high-school graduation,” Dr. Dietz claimed. “I think that Mr. Hinckley’s interest in the Beatles is the earliest sign that I’ve been able to discern that he became exceedingly interested in fame, in the notion of success, in fame in a way that would not require a great deal of effort.”

Early in his questioning, prosecutor Adelman asked, “whether at the time of the criminal conduct on March 30, 1981, the defendant, as a result of mental disease or defect, lacked substantial capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct?”

“On March 30, 1981,” Dr. Dietz replied, “Mr. Hinckley, as a result of mental disease or defect, did not lack substantial capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct.”

The witness went on to speak of the defendant’s “long-standing interest in fame and assassination” and “study of the publicity associated with various crimes.” John was able to think clearly about such matters as what bullets would do most harm and how he could get within range for a clear shot. John decided to shoot when he did, Dr. Dietz said, because “He viewed the situation as having poor security. . . . The Secret Service and the others in the presidential entourage looked the other way just as he was pulling the gun.

“Finally, his decision to proceed to fire, thinking that others had seen him . . . indicates his awareness that others seeing him was significant because others recognized that what he was doing and about to do were wrong.

“These are examples of the evidence that he appreciated the wrongfulness on March 30.”

While on the stand, Dr. Dietz quoted the defendant as telling him of the assassination attempt: “You know, actually, I accomplished everything I was going for there. Actually, I should feel good because I accomplished everything on a grand scale. . . . I did it for her sake. . . . The movie isn’t over yet.”

While Dr. Dietz was testifying, observers said that John glared at him and during a break, seemed to swear under his breath at the doctor.

Dr. David Bear, a psychiatrist testifying for the defense, had little experience in courtrooms. Perhaps that is why he seemed rather nervous. However, he was a top-notch doctor who had graduated first in his Harvard class of 1965 and his testimony was that of a most knowledgeable physician. He believed that John had been psychotic on March 30.

Both schizophrenia and clinical depression were present in the defendant, according to Dr. Bear. After being brushed off by Foster, Dr. Bear said, the accused had decided he must “rescue” her because she was “a prisoner at Yale.”

“Every single time a psychiatrist sees thinking like that,” he testified, “every time, not as a matter of opinion, as a matter of fact, that is psychosis.”

The psychiatrist discussed at length the film Taxi Driver and the defendant’s peculiar reactions to it and extreme identification with its mentally sick and homicidal protagonist. At one point, the issue arose of whether John, who had in some instances manipulated his parents into giving him money, could have been faking mental illness. Dr. Bear believed that highly unlikely because fakers usually report dramatic things like hearing voices or seeing visions. John denied having hallucinations. His symptoms were things like a lack of appropriate emotional response.

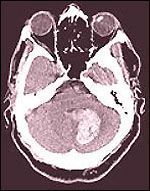

One piece of evidence that the defense tried to introduce through Dr. Bear was a CAT-scan that had been taken of John W. Hinckley Jr.’s brain. Lawyers for both sides said it had never before been admitted as evidence in an American courtroom and the judge dismissed the jury from the room before hearing arguments about its relevancy. Would Judge Parker make precedent by allowing this jury to see it?

There has for some time been a consensus among mental health experts that, like bipolar disorder (formerly “manic depression”), many if not most cases of schizophrenia have a biological basis. Proving that John’s brain differed from that of normal people would be vital in establishing his illness, the defense believed. It was also something he could not be accused of faking as well as something the jury could actually see with their own eyes.

Speaking of the CAT-scan, Dr. Bear said, “As an instrument for viewing the brain, I think it is absolutely unquestioned. It is considered the greatest diagnostic advance perhaps in the last fifty years.”

What exactly would it show about the defendant’s brain? He had widened “sulci,” the medical term for folds and ridges on the surface of the brain. Widened sulci are far more common in schizophrenics than normal people. “In one study from St. Elizabeths Hospital,” Dr. Bear claimed, “one-third of the schizophrenics had widened sulci. . . . whereas in normals, probably less than one out of fifty have them.”

The prosecution claimed that it had not been proven that the CAT-scan aided in a diagnosis of schizophrenia and thus, such evidence should not be presented to the jury.

After listening to the initial arguments about the CAT-scan, Judge Parker ruled that he would not admit it. Nine days later, he heard more expert testimony about this diagnostic tool and again ruled it out of bounds. Then he changed his mind and said the defense could show the CAT-scan.

When finally presented after so much intense legal wrangling, the CAT-scan photographs seemed anticlimactic. Slides of the defendant’s brain were displayed on a small screen. Caplan wrote that the scans “looked like slices of bruised and misshapen fruit.” A self-conscious radiologist, clearly unaccustomed to public speaking, pointed out in a shrill voice certain “abnormal” areas but few in the courtroom seemed terribly impressed.

Psychologist Ernst Prelinger and psychiatrist Thomas Goldman both took the witness stand for the defense, shoring up the claim that John was insane.

Disputing that claim was psychiatrist Dr. Sally Johnson, who had interviewed him longer than any other doctor. The 29-year-old wore her brown hair up in a bun and smiled easily as she confidently testified to disorders that she believed fell short of legal insanity. Becoming a public figure was a primary motive for John, Dr. Johnson believed.

John waved to her as she began testifying. He requested that his attorneys ask her if she “liked” the defendant. He started glowering at her as she gave testimony that was meant to be damning.

The defense requested that the movie Taxi Driver be shown to the jury. It was.

In summing up for the government, Adelman emphasized the defendant’s stalking of two presidents, his target practice, and his choice of the especially deadly Devastator bullets. He reminded the jury that, “at 1:45 when Mr. Reagan arrived, Mr. Hinckley is standing there. . . . And he doesn’t shoot then. He waited for the best shot.” The accused was not “out of control or in a frenzy” or he couldn’t have waited for the best opportunity to shoot.

He claimed that the defense had failed to adequately address the issue of whether John’s “ability to appreciate wrongfulness or conform his behavior to the requirement of the law was substantially impaired. . . . All these doctor’s CAT scans, delusions, fantasies, and everything else. Miles away from the question.”

Adelman was clearly offended by Dr. Carpenter’s having called his victims “bit players” in the defendant’s mind. “That’s an outrageous thought,” Adelman said, his voice rising, “that the President of the United States and a man shot in the brain are ‘bit players.'”

Vincent Fuller gave the closing statement for the defense. In a tone of sadness, he acknowledged that his client had perpetrated “the tragic shooting of four innocent victims.” He emphasized the isolated nature of the defendant’s life. “He lives in a world where the only reality is that which he makes for himself,” Fuller told the jury. John was not “exposed to the checks and balances we all need in our everyday lives, to know that we are making sense in our activities.”

Of John’s motive, Fuller said, “I suggest the ideation . . . that by stalking the president of the United States, he could in some way establish a relationship with the young woman, is bizarre.

“I submit to you that it is a result of a serious mental illness in which the defendant’s relation to reality in the true meaningful sense has been severed . . . “

Contrary to the prosecutor’s assertion, John was in a “frenzy,” an “internal frenzy . . that is going on in this man’s inner world, all built upon false premises, false assumptions, false ideas.”

Fuller repeated that the victims were “bit players in the mind of the defendant” not to “any of us here.” The characterization was of how they appeared in John’s “delusional state.” At the end of his summation, Fuller said that John’s delusions had “reached psychotic proportions” by March 1980 and said that “the Government has failed in its burden of proving that this defendant was mentally responsible” for his conduct on March 30.

After eight anguishing weeks of complex testimony, the fate of John Hinckley Jr. was in the hands of the jury. During the days they were out, Jack composed a press release to be read when the guilty verdict that he and others believed inevitable came in. It began, “Obviously, we are terribly disappointed by the guilty verdict for our troubled son, John, whom we love very much.”

Then word came that the jury had reached a verdict. The jury’s foreman handed the written verdict to Judge Parker. The jurist looked through it, a characteristically serious expression on his face. “The Court will read the verdict as tendered by the jury foreman,” Parker said. “As to Count 1, Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity. As to Count 2, Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity, As to Count 3, Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity.” And on he went through all 13 counts.

A wave of shock rippled through the courtroom. Even the defense attorneys had not expected victory. Jack Hinckley was to recall that “my head felt light.” Jo Ann let out a cry and she burst into tears as her husband hugged her.

Then the jury was individually polled to see if that was the verdict of each. Yes, each replied to every count.

Judge Parker said, “The date of further proceedings in this matter, including sentencing, will be set for July 12 at 10:00 a.m.” Then the judge caught himself and shook his head. There would be no sentencing in this case although there would certainly be confinement in a mental hospital. “The defendant shall be remanded immediately,” he said.

French Smith (AP)

Suddenly the court exploded as reporters ran to the doors and astonished people began talking over each other. That was just the beginning of the uproar that would follow this verdict. Commentators competed to denounce it. James J. Kilpatrick called it a “travesty of justice.” Joseph Kraft thought it “did violence to common sense.” High-ranking members of the Reagan administration Attorney General William French Smith and Treasury Secretary Donald Regan went on talk shows to vent their outrage at the verdict.

Donald Regan (AP)

The jurors, people who had looked past class and race to do their duty as citizens, were the targets of extraordinary criticism. As Caplan aptly noted, “In the days after the verdict of acquittal, the jurors might have felt like Vietnam veterans, returning to a country that expressed a contempt for its soldiers instead of fury over a long war.”

Jury deliberations had been careful, thoroughgoing, and tense. The first order of business when the door to the jury room slammed shut, however, was the mundane one of choosing a foreperson. Each juror threw his or her name into the hat of retired janitor Roy Jackson, 64. Since it was his hat, he did the drawing and pulled out his own name.

Some immediately thought he was not guilty by reason of insanity, others that he was definitely guilty. “So we took out the evidence,” said secretary Belinda Drake, 23, “and put our personal feelings aside.”

Some jurors felt the suicidal tendencies in his letter to Foster indicated insanity. Others felt his attempts to get money from his parents showed he was sane. They differed on how to interpret his relentless trip taking. Janitor Glynis Lassiter argued, “Nobody, no matter how much money he has would spend it like that. He pays a jet fare and stays a day. I can’t see that.” But school cafeteria worker Maryland Copelin said, “Anytime you can buy airplane tickets and go anywhere you want and get the money to do it, you’re sane.”

Although forbidden to discuss the case, even with each other, when they weren’t in session, they could not stop thinking about it. Ruggedly built Lawrence Coffey lost sleep over it. He remembered lying in bed and compulsively scrutinizing the evidence. “I lay there thinking about his letters to Jodie and to his parents,” Coffey said.. “I felt sure he wasn’t in his right mind when he shot those people.”

In the middle of their deliberations, the jury changed forepersons. Jackson had a pronounced stutter and some of the others felt he was not comfortable with the amount of speaking that being foreperson required.

Lawrence Coffey, 22, became foreperson. The group debated more about the defendant’s peculiar mental state. At last, they all voted not guilty by reason of insanity.

When the media descended on the jurors, Coffey explained their verdict by saying, “The prosecutor’s evidence was not strong enough.” Juror George Blyther commented, “We had to give a judgment back the way it was given to us. The evidence being what it was, we were required to send John back insane.”

Two jurors made an attempt to distance themselves from the verdict. Nathalia Brown and Maryland Copelin told a press conference that they had been pressured into changing their votes. Complained Brown, “I felt I was on the brink of insanity myself going through this.”

A few commentators pointed out that, since the burden had been on the prosecution to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that John Hinckley, Jr. was sane, they had come to the only legally appropriate decision. Proving that a man who believes he will win the esteem of one stranger by killing another is mentally responsible is no mean task.

Indeed, some wryly remarked that proving many people sane would be difficult. A recovered President Reagan made this point. “If you start thinking about a lot of your friends,” he commented, “you would have to say, ‘Gee, if I had to prove they were sane, I would have a hard job.'”

As a result of public distaste for the verdict, much of the law on the insanity defense was re-written. Many states narrowed the defense and some shifted the burden of proof from the prosecution to the defense, making Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity an “affirmative” defense. Some narrowed the range of testimony psychiatric experts could give. Twelve states started a possible verdict of “guilty but mentally ill” but still retained the possible verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. Montana, Idaho and Utah have abolished the insanity defense.

Many people perceived John as having “gotten away with” shooting four people, one of whom was the president of the United States and another of whom would be permanently afflicted because of the attack. There was widespread fear that he would soon be out and about again.

A common scenario, at least in urban folklore if not in real life, is that of the wily, sophisticated criminal who fakes insanity, then goes to a mental hospital and is miraculously “cured” only to stalk the streets and victimize again.

(AP/Wide World)

However, John was immediately taken to St. Elizabeths (it has no apostrophe) hospital for the mentally ill that is operated by the Department of Mental Health. It has a section for people who have been referred through the court called the forensic services administration.

There he was given a battery of tests to determine his psychological status and try to ascertain his potential for danger. After those tests were analyzed, a report concluded, “his defective reality testing and impaired judgement combined with his capacity for planned and impulsive behaviors makes him an unpredictably dangerous person. Mr. Hinckley is presently a danger to himself, Jodie Foster, and to any other third party whom he would consider incidental in his ultimate aims.”

By late 1983, however, he appeared to be responding to treatment. He seemed less depressed. He also told therapists that he was no longer obsessed with Jodie Foster and had fewer thoughts of violence.

In 1983 he also gave an interview to Penthouse in which he described a “typical day” for him. “I see a therapist,” he said, “answer mail, play my guitar, listen to music, play pool, watch television, eat lousy food, and take delicious medication.” He also said that other patients sometimes ask for his autograph and that he enjoys his notoriety although not the special restrictions that go with it.

Two of those restrictions were lifted in 1984. He was allowed telephone privileges and the hospital quit censoring his mail. In 1985, he was permitted to take accompanied walks around the grounds of St. Elizabeths.

John filed a Motion for Conditional Release with the courts in 1986. A “conditional release” was a transfer to a less restrictive ward and “city privileges one day per month.” The latter meant being able to spend one day out of the month unaccompanied and with no restrictions. The hospital recommended against granting either request in an affidavit saying, “It is not possible to state that Mr. Hinckley would not present a danger to the community if granted such privileges at this time.” The court denied both requests.

However, on December 28, 1986, St. Elizabeths most infamous patient was allowed a 12-hour leave to visit his family at a Prison Fellowship Ministries center. He had a hospital escort and the car he traveled in was closely tailed by the Secret Service who had been notified of the visit.

On March 27, 1987, St. Elizabeths told the court that it thought John was ready to visit his family off hospital grounds for the Easter holidays. This time, the hospital said, he would not need an escort. He had been making rapid strides in therapy, was not the complete loner he had been, and had shown improvements in major areas.

Government attorneys requested that this be denied.

Psychiatrist Glenn Miller reported that the patient had shown remorse for the shootings and quoted John as saying “that he remembered Mr. Brady in his prayers.” He also said that John realized that his fixation on Jodie Foster was “ridiculous” and that she no longer played much part in his “sexual or psychic life.”

Unfortunately for John’s hopes of a holiday, Dr. Miller dropped a bombshell during questioning by John’s own attorney, Vincent Fuller.

Fromme (AP)

“His judgement is not perfect,” Dr. Miller said, “He writes letters to some of his pen pals.” One of those pen pals was serial murderer Ted Bundy. Another was Lynnette “Squeaky” Fromme who had been convicted of trying to assassinate President Gerald Ford. He had also tried to get hold of Charles Manson’s address.

Roger Adelman asked for and got a court order to search John’s room at St. Elizabeths. That search proved somewhat frightening. Twenty photographs of Jodie Foster were found hidden there. All had been collected after his hospitalization. That collection was taken away from him.

There was no Easter holiday outside St. Elizabeths for John.

In 1988, the Secret Service received a letter from a mail-order house saying it had received a letter from John requesting a nude drawing of Jodie Foster. Apparently, his fixation on the actress had not abated after all.

Psychiatrists believed Hinckley made significant improvement in his mental state so he was allowed to leave the grounds of St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., for visits in 1999.

In April 2000, he was allowed unsupervised furloughs, but the privilege was revoked that May when guards discovered a smuggled book about Jodie Foster in his room—Hinckley is prohibited from having any material about the actress.

A court hearing was held in June 2007 to consider Hinckley’s requests for greater freedom. At that time, Hinckley was already allowed four-night visits to his family home in Virginia. Officials at St. Elizabeths supported Hinckley’s bid for greater freedom and submitted a proposal to the court outlining the oversight its doctors believed he should have if allowed more time outside the institution.

Hinckley sought to extend his home visits to two weeks and be allowed to apply for a driver’s license.

Doctors testifying on Hinckley’s behalf said that both his psychosis and his depression were in remission. They also said more freedom would help him develop the social skills he needed to function appropriately in the free world.

An article by Matt Apuzzo in USA Today reported that doctors testifying for the government “said the hospital’s proposal was too vague and left Hinckley with too much unstructured time in the community without appropriate oversight and counseling.”

U. S. District Judge Paul L. Friedman ruled that Hinckley’s visits would be extended to six days but refused to rule on Hinckley’s additional requests. Friedman explained, “The reasons the court has reached this decision rest with the hospital, not with Mr. Hinckley. Unfortunately, the hospital has not taken the steps it must take before any such transition can begin.”

Two years later, in June 2009, the same judge found that the hospital had taken the proper steps to allow Hinckley the proposed transition. He made this ruling despite assertions by government witnesses that Hinckley still presented a danger to the community. A CNN Justice article noted that prosecutors contended that Hinckley “continues to maintain inappropriate thoughts of violence.” The pointed to a journal that hospital officials had asked Hinckley to keep as showing that his relations with women were alarming.

Hinckley had recently engaged in sexual relations with two women, one of whom had bi-polar disorder and the other of whom was in a long-term relationship with someone else. He had also been dating two other women. Prosecutors argued that these relationships indicated an “increased risk for violence due to depression or due to a request to act out to demonstrate his love for a woman.”

Prosecutors were also concerned because Hinckley had recently re-recorded a song he had written before the assassination attempt entitled Ballad of an Outlaw that they described as “reflecting suicide and lawlessness.” However, according to CNN Justice, “Hospital officials said he was trying to take responsibility for his past by recording the song again.”

Judge Friedman ruled that Hinckley would be permitted to visit his mother more frequently, spend more time away from the hospital and get a driver’s license. Judge Friedman stated, “Hinckley will not be a danger to himself or to others under the conditions proposed by the hospital.”

Taxi Driver, Columbia Pictures.

“The Insanity Plea on Trial,” Newsweek, May 24, 1982.

“It’s Just Gonna Be Insanity,” Time, May 24, 1982.

“Insane on All Counts,” and “Is the System Guilty?” Time, July 5, 1982.

“A Controversial Verdict” and “Hinckley Goes to the Hospital,” Newsweek July 5, 1982.

“The Insanity Defense and Me,” Newsweek, September 20, 1982.

Caplan, Lincoln, The Insanity Defense, David R. Godine, Publisher, Boston, Massachusetts, 1984.

Clarke, James W., On Being Mad or Merely Angry Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1990.

Hinckley, Jack and Jo Ann with Sherrill, Elizabeth, Breaking Points, Chosen Books, The Zondervan Publishing House, Grant Rapids, Michigan, 1985.

Low, Peter W., Jeffires, Jr., John Calvin, Bonnie, Richard J., The Trial of John W. Hinckley Jr., The Foundation Press, Inc., Mineola, New York, 1986.

The World Book Encyclopedia, World Book, Inc., 1985.

Apuzzo, Matt. “More freedom for Hinckley no certainty.” USA Today, June 20, 2007.

“Biography: John Hinckley, Jr.” WGBH American Experience. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/reagan-hinckley

“Court gives would-be assassin John Hinckley more freedom.” CNN Justice. June 17, 2009.