The Unthinkable — Children Who Kill and What Motivates Them — The Crime Library — The Unthinkable — Crime Library

Jesse Pomeroy was fourteen when he was arrested in 1874 for the sadistic murder of a four-year-old boy. He was quickly dubbed “The Boston Boy Fiend.” His rampage had begun three years earlier with the sexual torture of seven other boys. For those crimes Pomeroy was sentenced to reform school, but then he was released early. Not long afterward he mutilated and killed a 10-year-old girl who came into his mother’s store. A month later, he snatched four-year-old Horace Mullen. He took Horace to a swamp outside town and slashed him so savagely with a knife that he nearly decapitated the child. Because of his strange appearance—he had a milky white eye—and his previous behavior, suspicion turned to him. When he was shown the body and asked if he’d done it, he responded with a nonchalant, “I suppose I did.” Then the girl was found buried in his mother’s cellar and he confessed to that murder, too. He was convicted and sentenced to death, although a public outcry against condemning a child to hang commuted the sentence to four decades of solitary confinement.

Mary Flora Bell wanted to “hurt” someone. She was an angry child, the product of an unsettled home in which chronic abuse was the norm. She had a friend, Nora Bell, and they often did things together. When Mary was eleven, she and Nora lured a boy to the top of an air raid shelter. When he fell and was injured, it was thought to be an accident. Two weeks later, the corpse of four-year-old Martin Brown was found, another assumed accident. Then police discovered notes that indicated that someone was taking responsibility—two people, in fact, who called themselves “Fanny and Faggot.” Then Mary showed up at Martin’s home so she could “see him in his coffin.” Two months passed and another local toddler, three-year-old Brian Howe, turned up missing. When Mary suggested that he might be playing on a certain pile of concrete, searchers looked where she indicated and found his body. He’d been strangled and his legs and stomach had been cut with a razor and scissors. The medical examiner believed it to be the handiwork of a child.

Mary and Norma were brought in; Mary made up a story but Norma described watching Mary kill the boy. They went to trial in 1968 in England, where Mary was convicted of two counts of manslaughter. People called her “evil” and a “bad seed,” in part because she seemed so indifferent to the proceedings against her. A court psychiatrist said that she was manipulative and dangerous.

Willie Bosket had committed over two thousand crimes in New York by the time he was fifteen, including stabbing several people. The son of a convicted murderer, he never knew his father but revered him for his “manly” crime. Just before he was sixteen, his crimes became more serious. Killing another boy in a fight, he then embarked upon a series of subway crimes, which ended up in the deaths of two men. He shot them, he later said, just to see what it was like. It didn’t affect him. He knew the juvenile laws well enough to realize that he could continue to do what he was doing and yet still get released when he was twenty-one. He had no reason to stop.

Yet it was his spree and his arrogance that brought about a dramatic change in the juvenile justice system, starting there in New York. The “Willie Bosket law,” which allowed dangerous juveniles as young as thirteen to be tried in adult courts, was passed and signed in six days. Willie went on to commit more crimes, although none as serious as murder, and ended up with prison terms that ensured that he would spend the rest of his life there.

Cindy Collier was 15 and Shirley Wolf 14 when they started prowling condominiums in California in 1983. They knocked on doors at random to gain admittance. An elderly woman let them in and sat chatting with them as they thought up a plan to steal her car. Shirley grabbed her by the neck while Cindy found a butcher knife and tossed it to her. Shirley stabbed her victim 28 times, even as the old woman begged for her life. They fled the scene, but were soon arrested. Both confessed that the murder was “a Kick” and that they wanted to do another one. They thought it was fun.

In 1964, when Edmund Kemper was 15, he shot his grandparents, killing them both. He’d been imagining this act for some time and had no regrets. The California Youth Authority detained him in Juvenile Hall so that they could put him through a battery of tests administered by a psychiatrist. Since the results indicated that he was paranoid and psychotic, he was sent to Atascadero State Hospital for treatment. There he learned what people thought about his crime and worked hard to convince his doctors that he had recovered. Although he was labeled a sociopath, he actually worked in the psychology lab to help administer the tests to others. In the process, he learned a lot about other deviant offenders.

Kemper was released five years later, although he remained under the supervision of the Youth Authority. His doctors recommended that he not be returned to his mother’s care, but the Youth Authority ignored this. After Kemper murdered and dismembered eight women over the next five years, these same doctors affirmed his insanity defense. In fact, even as he was carrying parts of his victims around, a panel of psychiatrists judged him to be no threat to society.

In 1998, 14-year-old Joshua Phillips bludgeoned his 8-year-old neighbor, and then hid her body beneath his waterbed. Seven days later his mother noticed something leaking from beneath the bed. Joshua claimed that’s he’d accidentally hit Maddie in the eye with a baseball. She screamed and he panicked. He then dragged her to his home where he hit her with a bat and then stabbed her eleven times. His story failed to convince a Florida jury, who convicted him of first-degree murder.

For many people, children who kill are monstrous, unthinkable. Yet where they once were rare deviants, they are now becoming more commonplace. Let’s look at the types of killings that children initiate to see the variety of motives involved.

Kids who kill fall into different categories, according to their traits, situations, and motivations. Some kills are accidental, such as those involving kids who find their parents’ guns, but many occur within a specific type of context and have motives. Most of the experts categorize these killings by kids as:

1. Inner city/gang killers – these are kids who grow up in violent environments and who may have violent role models, such that their typical mode of response, whether for self-defense or just to get what they want, is violence. This also includes gang killers, or children who are pressured from within a gang to kill. They feel more powerful as a member of the gang, so they will do what it takes to get respect. In fact, within some gangs any restraint on violence is viewed as weak.

2. Killing within a family: Kids who kill members of their family for reasons other than an accident, feel pressured by demands, abuse, hatred, desire for gain, and even by the need of other family members. One 14-year-old enlisted this brother to help him murder their parents, and one mother provoked her son into killing his father. A fourteen-year-old in China killed his family because he thought his mother was not taking care of him properly. When he was ill one night, she ordered him back to bed. Instead, he stabbed his father 37 times, his mother 72 times and his grandmother 56 times. Then he washed his hair and watched a videotape.

3. Cult killings: 16-year-old Roderick Ferrell killed the parents of his former girlfriend in order to steal their car so he could take his friends—members of his vampire cult—to New Orleans. A lot of kids identify themselves as Satanists because it gives them the feeling of power over others and the mystique of having secret associations with another world. It also gives them license to do things like rob, damage property, and kill. Sometimes they decide that human sacrifice is necessary to increase their powers, so they kill. Ferrell claimed that he needed many victims in order to open the Gates of Hell.

4. Pathology: Sam Manzie, 15, opened the door to eleven-year-old Eddie Werner, who was out raising money for his school. He invited the boy in, then raped and strangled him, hiding Werner’s body outside. Manzie had been the victim of a child abuser and had shown signs of serious mental illness. His parents had desperately tried to get him help and were convinced that he would become violent. A doctor interviewed the boy for about ten minutes and told the parents to take him home. They were over-reacting, he said. Only three days later he murdered Werner. Many people have a difficult time believing that children can be mentally ill, but they suffer depression and paranoid schizophrenia just like adults. When it goes undiagnosed and untreated, it can spell trouble.

5. School killers: They generally act on a perceived wrong done to them by others and view a climactic closure to the situation as the only way out. Frustrations accumulate into rage that motivates a spree. Michael Carneal, who shot into a prayer group in Paducah, Kentucky, was constantly baited by the other students. They said he had “Michael germs” and stole his lunch. One day he had a gun and even then the other boys taunted him. Finally he decided to act out and he ended up killing three students.

6. Killing committed during another crime: Fifteen-year-old Sandy Shaw lured James Kelly, 24, into the Nevada desert in 1986 so that she and two friends could rob him. They needed money to post bail for Sandy’s boyfriend. They lifted $1400 and then shot him six times. They even took friends out to see the body.

7. Sexual killings: James Pinkerton Kelly, 17, killed a neighbor. First he sliced open her stomach and ejaculated into the wound. Then he slit her throat and cut off her breasts. Before he was arrested, he managed to do the same thing to another woman.

8. Hate crimes: Two boys, 17 and 14, shot a man in the head and then ran over him repeatedly with their car just because he was gay. Such crimes begin with anger and hate and often involve a build-up of rage. However, there are cases where the killings happened just so the killers could brag to their friends that they’d rid the world of such a person.

9. Kids who kill themselves. Five teenagers killed themselves in Goffstown, New Hampshire over a period of two years in the early 1990s. Another kid, Jeremy Delle, went to school and blew his brains out in front of thirty other students. Such kids tend to be lonely and depressed, but also want their self-violence to have painful reverberations in the lives of others. Some of the school shooters were suicidal as well, and wanted to take others down with them.

10. Kids who kill their babies: In upstate New York, a fifteen-year-old girl gave birth to a baby. She cleaned it up, wrapped it in a towel and plastic bag, and then tossed it down an eleven-foot embankment. She was arrested and she told the police that her mother, who did not know that she was pregnant, would have gotten upset with her. Quite often either the girl involved, or a couple, have done this to avoid parental disapproval or just to avoid having the responsibility of a child while they were children themselves. Sometimes the girls claim postpartum depression.

Perhaps the most disturbing motive for killing is just for the thrill of it. Let’s have a look at two cases, one historic, the other contemporary. We’ll begin with Leopold and Loeb.

Leopold and Loeb

The year was 1924. Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, both 19, were close friends. Loeb worshipped power and Leopold worshipped Loeb. One day in May, they decided to find a child to kidnap for ransom and murder. They had devised “the perfect crime,” they believed, and had rehearsed it down to the letter. The day finally arrived and they randomly selected young Bobby Franks outside his school. He knew them, so he climbed into the car. They hit him with a chisel, then smothered him. Afterward they drove some distance away so they could strip him and pour acid on his face and genitals to prevent people from identifying him. Finally they tossed him in a culvert where Leopold often went birding, and went home to write a ransom note.

Unfortunately for Leopold, he dropped his glasses near the culvert and from the unique hinges, the police traced them to him. However, since he often went to the area, he quite believably said that he’d dropped them while birding. The police continued to look into his background, along with that of Loeb, and eventually found samples of Leopold’s typing that matched the ransom note. They did not find the portable typewriter in his possession, but when they caught Loeb in a lie about his car, he rolled on Leopold. They both confessed.

It turned out that the murder had been committed to entertain two bored intellectuals. They wanted to test their ability to plan and carry out a crime without being caught. It hadn’t mattered which child. They hadn’t targeted anyone in particular. They just needed a child who couldn’t fight back. Neither expressed remorse or thought that what they had done was reprehensible.

The press reported this kidnap/murder as unique in the annals of American crime. There had been no particular motive other than to see if they could get away with it. They were monstrous, without human feeling. The like had never been seen.

While that may have been true in 1924, it’s no longer true today, and the thrill killers are getting younger and younger.

The James Bulger Case

At 3.39 p.m. on February 12, 1993, a surveillance camera in the Bootle Strand shopping center in Liverpool, England, filmed Robert Thompson and Jon Venables casually taking two-year-old James Bulger by the hand. They were just outside the butcher’s shop, where James’s mother was delayed when the butcher misunderstood her order. Having lost her first child to a miscarriage, she tried always to be vigilant, but to her shock, James was gone.

Thompson and Venables, both age ten, were skipping school that day, shoplifting and looking for something to do. For a lark, they decided to see if they could get away with a kidnapping. According to reports, they had already tried with a four-year-old, who’d resisted them. Then they came upon James. With him in tow and Thompson leading the way, they left and headed toward the railroad tracks at Walton, over two miles away.

Along the way, as many as thirty-eight people spotted them and some even inquired what they were up to, but no one stopped them. Several had noticed that James had a head injury and appeared distressed. They did not realize that the boys had dropped him on his head. One woman wanted to escort him to the nearby police station, but no one would watch her dog so she let the boys go off by themselves.

The lifeless, battered body of young James was soon discovered on the tracks. A train had cut it in half. He still wore his jacket but his bottom half had been stripped of pants and underwear. The boy was covered in blue paint, his lip had been ripped, an eyelid torn, and there were numerous wounds to his scalp. Marks on his face had the appearance of horse’s hooves. Clearly the boy had not just fallen onto the tracks. Someone had seriously injured him beforehand and there was some possibility of sexual assault.

During the weeklong investigation, an innocent boy named Jonathan Green was arrested first, only because he’d been turned in by his own father. Yet he hadn’t been near Bootle Strand that day, so he was released.

Then suspicion turned on Thompson and Venables. They quickly confessed, each pinning the blame on the other, and were taken into custody.

The trial lasted three weeks, beginning with extensive descriptions by the prosecutor of the brutality of the crime. Venables leaned back and cried, but Thompson merely appeared curious. The impression was formed that he was the ringleader and Venables the follower (the same perception as with Loeb and Leopold), although Venables was the one who clearly stated in his confession, “I did kill him.”

At first, the boys were referred to as A and B, but then the judge allowed their names to be published in the newspaper, persuaded that this was in the best interest of the public. After all, they were being tried as adults. In British courts, children below the age of ten are deemed incapable of forming intent to kill, but between the ages of 10 and fourteen is a gray area.

In court, the videotape of them taking the boy was played for the jury, as were their confessions. Those tapes alone—twenty of them—took up nearly a week of court time. The boys admitted to splashing James with blue paint, to pelting him with bricks and then hitting him with an iron bar. They said that they had laid him down on the railroad tracks, but they declined to admit to what forensics evidence indicated, that they kicked him in the head and groin and that they removed his pants and underwear for the express purpose of sexual fondling. There was some speculation that they had pushed batteries into his anus, but they also denied this. Horrifyingly, they both said that they’d continued the attack because “he just kept getting up.”

While the people of Britain who were ready to hang them believed that all along they’d plotted to kill a child—any child—there was no evidence to support this. The boys had taken no weapons and had ended up using whatever was available. It appeared to be the case that they’d simply come up with the prank of taking a child, and then unable to think of a way to end it, they’d simply killed him.

Expert testimony from psychiatrists affirmed that these boys were not insane; they had understood the nature of their crime and knew it was wrong. Thus, their state of mind at the time of the crime was not psychotic. In essence, they acted with adult consciousness. The pathologist confirmed that the wounds showed brutal intent.

It was decided that the boys would not do well on the witness stand, so they were not offered in their own defense. The jury deliberated for several days and then came back with a verdict: both boys were guilty of abduction and murder, although no verdict was reached regarding the attempted abduction of another child. Judge Michael Morland sentenced them to a rather indeterminate prison term: “very, very many years”, until it was clear they had been rehabilitated and were no longer a danger to society.

What did not come into court, but what the psychiatrists had found, was that both boys were from troubled homes. Thompson had been abused. Together, they seemed to spur each other on to do things that neither would have done alone. Had an adult actually intervened, they would have given James over. They were scared of getting into trouble and they didn’t understand the irrevocable nature of death.

A month later, the judge’s sentence was clarified: the boys were to serve a minimum of eight years, i.e., until they are eighteen years old. This sentence was much shorter than expected and caused a public outcry. Home Secretary Michael Howard changed it to a minimum of fifteen years.

The boys’ lawyers argued against this, citing the fact that the Howard had not looked at the mitigating circumstances stated in the psychiatric reports. Their appeal was upheld. When the Home Secretary counter-appealed, the lawyers took the case to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights. They wanted the sentence decided by a judge, not by government officials who depended on the public good will.

The European Court ruled that the two boys had not received a fair trial and stated that it was not correct for the Home Secretary to set the minimum punishment. The Human Rights Convention guarantees a fair hearing before an independent and impartial tribunal. The lawyers will seek parole for the boys when they reach the age of 18.

Blake Morrison covered the trial in As If: A Crime, A Trial, A Question of Childhood because it was a precedent-setting case and because it seemed to draw forth a brutal sort of rage from the crowd, who wanted to lynch the two ten-year-olds on the spot. His own opinion is that the trial failed to bring out why these children had done what they did, and in failing that, the court did not attend to matters of justice.

Nevertheless, we must ask why some children are so callous as to kill others just to entertain themselves. Increasingly more psychologists are examining the notion of childhood conduct disorders from which kids develop into sociopaths.

Criminal Intent

In 1999, eleven-year-old Nathaniel Abraham was on trial for murder–the youngest defendant to date in a murder trial in Michigan. The country was disturbed that such a young boy might be able to form criminal intent—and not everyone agreed that he could—but in Michigan law, there’s no age limit for when a child can be waived to adult court. In other words, there’s no limit to when he can think through his or her actions with adult consciousness.

Abraham was so waived, charged with shooting a stranger, Ronnie Greene, 18, outside a store in Pontiac, Michigan. He had a stolen rifle and allegedly had bragged about planning to shoot someone. He practiced on targets and then when he’d actually shot Green, he’d boasted about it afterward. Only when he was arrested did he claim that the shooting was accidental. He was eventually convicted of second-degree murder.

Part of the problem was that there was no protocol for assessing diminished mental capacity in a child of Abraham’s age. However, psychologists and social workers are becoming increasingly more aware of the special types of behavior problems among children and adolescents. Some of these are signals that violence may lie ahead.

The Variety of Disorders

There are many overlapping conduct disorders that play into juvenile crime., although given a child’s developing and changing personality, it is difficult to diagnose mental disorders among adolescents. It’s also true that many attitudes and behaviors characteristic of teenagers, such as anger, defiance, and restlessness, match the symptoms of several disorders.

In general, a conduct disorder is a persistent pattern of behavior during childhood and adolescence that includes:

- violating social rules

- aggression

- property damage

- lies

- stealing

There are six different categories of conduct disorder:

- Conduct Disorder – a behavioral problem involving persistent violations of the rights of others.

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder – Such youths usually exhibit a pattern of defiant and disobedient behavior, including resistance to authority figures. This includes recurrent temper problems, frequent arguments with adults, and evidence of anger and resentment.

- Disruptive Behavior Disorder – this is a category for pervasive restlessness and aggression that doesn’t quite qualify for the first two categories, but is nevertheless a concern.

- Adjustment Disorder: With Mixed Disturbance of Emotions and Conduct – an array of antisocial behaviors that occur within three months of a stressor.

- Adjustment Disorder: With Disturbance of Conduct – similar to the other adjustment disorder, but with antisocial behaviors only, not emotional components.

- Child or Adolescent Antisocial Behavior – a category for isolated antisocial behaviors that fail to support an outright mental disorder

Many of these have been linked with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD or ADD), which actually represents two separate problems. Children may have ADD (a problem keeping their attention focused) or ADHD (a problem with restless behavior and attention). Disorganization is common and the child may lose personal items regularly. Even when spoken to directly, the child can’t provide feedback when asked. Hyperactive children frequently get into minor difficulties.

Children with attention and behavior problems like these may actually signal that they are developing into psychopaths or children without empathy or remorse.

Children without a Conscience

In a study of eighty-one boys in a residential treatment program, symptoms of aggressive conduct disorder, along with lying and stealing, were predictive of adolescent psychopathy in those aged 14 to 17. In other words, if they had a conduct disorder and also had acted in some antisocial manner, it was more likely than not that they were psychopaths.

In another study, the two factors in young offenders indicative of psychopathy were impulsive conduct problems and callous attitudes. These children develop attitudes of grandiosity and they shun responsibility. They’re also susceptible to boredom.

In a long-term study, children with psychopathic personalities were shown to be stable offenders (having more repeat offenses), were prone to instigating the most serious offenses, and were more impulsive.

To sum this up, childhood psychopathy has proven to be the best predictor of increased antisocial behavior in adolescence, especially in boys who were hyperactive, impulsive, and suffered from attention deficits.

Common traits in the background of psychopathic children include:

- a mother exposed to deprivation or abuse as a child

- a transient father

- a mother who cannot maintain stable emotional connection with child

- low birth weight or birth complications

- unusual reactions to pain (especially to insult)

- lack of attachment to adults

- failure to make eye contact when touched

- low frustration tolerance

- sense of self-importance

- transient relationships throughout childhood, or close association with another like him

- cruelty toward others

- animal abuse

- lack of remorse for hurting someone

- lack of empathy in friendships

How does this apply to kids who kill? How do they get this way? Is it something in their environment, something in how they were raised, or something in their genes?

Some psychologists claim that it’s mostly learned through cultural images and role models. Let’s have a look at what an expert on “killology” has to say.

Not only has the perpetuation of youth violence become an alarming issue in America, but also the fact that kids are shooting other kids with remarkable accuracy. Michael Carneal, who shot eight times into a prayer group in Paducah, Kentucky in 1998, managed to get eight hits, although he’d never before shot an actual handgun. Five of the victims were shot in the head and three in the upper torso. Three died and one was paralyzed for life.

Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman, a West Point military psychologist, says that violent television and violent videogames play a significant role. They condition children to become violent without teaching them the consequences. Grossman, who trains health professionals on how to prevent killing, wrote On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society. He discusses the sophisticated ways that societies have found to overcome the instinct to avoid killing, and with media expert, Gloria DeGaetano, has written Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill – a call to action against media-inspired violence. In short, the same techniques of social reinforcement that are utilized with soldiers are being turned on kids.

According to them, thirty years of scientific studies support the fact that violent programs desensitize children to violence. While the murder rate doubled between 1957 and 1992, the aggravated assault rate — the rate at which people are attempting to maim or kill one another – has multiplied many times more.

“In the workshops I conducted for teachers ten years ago,” says DeGaetano, who once worked as a police officer, “I predicted that we would soon see more twelve-year-olds committing unspeakable crimes like mass murder.” Although only a few may act out, he admits, all of our children are being damaged by the high doses of violence, because increasingly more brutality is becoming acceptable as part of life. “Sensational visual images showing hurting as powerful and domination of others as permissible are dangerous.”

We have to be taught to kill, Grossman claims. It doesn’t come naturally. “Within the midbrain,” he says, “there is a powerful, God-given resistance to killing your own kind. Almost every species has it. Only sociopaths lack this violence immune system.” Even with trained soldiers, only a percentage of them can easily bring themselves to actually kill in situations other than self-defense.

The training methods used in the military to prepare soldiers to kill include:

-

Brutalization – put through a program of verbal abuse to break down one set of values and install a new set that makes violence acceptable

-

Classical conditioning – associating a stimulus with a response according to a specific reinforcement schedule, such as violence linked to pleasure

-

Operant conditioning – another type of conditioned response that relies on a reward for an initiated action

-

Role models – the drill sergeant personified violence and aggression

The same factors are used in violent media programming. From young ages, kids are trained to accept violence as a natural part of life. Cartoon characters batter each other. In the early 1990s The Journal of the American Medical Association published a definitive study on TV violence. Comparing regions with television to regions without, and keeping most other factors the same, it was found that in every society where television was introduced, there was an explosion of violence on the playground. Within fifteen years, the murder rate had doubled, which is “how long it takes for the brutalization of three- to five-year-olds to reach the prime crime age.” In one Canadian town in which TV was introduced in 1973, there was a 160% increase in shoving, pushing, biting and hitting among young children. In control communities observed during the study, there were no such changes.

Children come to associate violence with entertainment. They eat and drink while watching, so that violence becomes part of a pleasing routine. They laugh when there’s violence in comedies and eagerly ask to see the most violent films. The stimulation associated with this programming is erotic. Interactive videogames also have operant conditioning features, rewarding violent acts that are accurate with higher scores. They learn to point and shoot, point and shoot. The “targets” look human, but the consequences of actually taking a human life are never realized in games. “Our children are learning to kill,” says Grossman, “and learning to like it.”

As for role models, not only does the media make kills larger than life, even heroic, but kids learn from other kids as well. Three months before the school killings in Jonesboro, Arkansas, another 14-year-old child in Stamps, Arkansas, hid in the woods and fired at his schoolmates as they came out of school. This was fifteen days after the sensational killings in Pearl, Mississippi. After the Columbine massacre, there were copycat attempts around the country to do the same thing on a grander scale, and a number of disenfranchised kids expressed admiration for the two suicidal shooters.

Television networks pay attention (in great detail) to attention-starved kids and that provides role models and rewards.

The solution, Grossman says involves the following:

- Gun control

- Supervision of television programs

- Purchase of nonviolent videogames

- Pressure the media to stop glorifying killing and killers

- Learn what children can handle at different ages and use more controls

- Teach children the consequences of violence

According to a 1999 study by the American government, by the time a child reaches the age of 18, he or she will have seen 200,000 dramatized acts of violence and 40,000 dramatized murders. Fully half of the videogames that a typical seventh-grader plays with are violent. Through this exposure, some troubled children develop a taste for violence. The boundary between fantasy and reality that adults can distinguish is much more difficult for children. Add to that the desensitization and conditioning that goes on daily from the media and it’s clear that violent programs do have a negative impact.

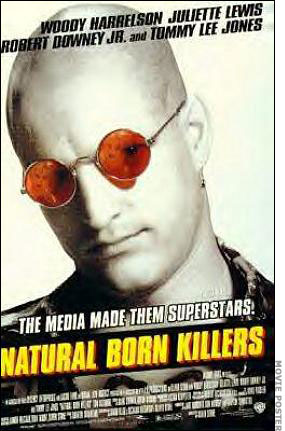

While media programming might not be solely to blame, some of the recent school shootings were admittedly influenced by violent games or images:

Barry Loukaitis, 14, who killed a teacher and two classmates in 1996, loved the film Natural Born Killers, and identified with the kid “Jeremy” (in Pearl Jam’s rock video), who went to school to kill others and then himself. Other kids have identified role-playing games such as Dungeons and Dragons or Vampire: The Masquerade as giving them the feeling they could act out on aggressive impulses. Two boys who killed the mother of one of them by stabbing her 45 times admitted that they’d been inspired by the teenage slasher movie, Scream. One of them told a friend that the slayings in the film were “cool,” and that “it was the perfect way to kill someone.”

Grossman certainly has a compelling argument, but there’s also something to be said for the biological studies of violence. Let’s examine a recent one.

After Joshua Phillps killed his eight-year-old neighbor and stuffed her body beneath his waterbed, he went on trial for murder. At the time, there was a theory that violence was somehow coordinated with abnormal EEGs, or heart rhythms. If such a correlation could be proven, then there might have been a physiological explanation for what he did. In other words, he just followed through on what his brain ordered him to do.

However, this theory failed to pan out. Until proven otherwise, he had nothing to blame but himself.

Nevertheless there are researchers who firmly believe that violence is clearly the product of some kind of physiological imbalance. Some say it’s almost entirely a matter of chemical interactions in the brain, while others believe that physiology and the environment are interconnected.

Debra Niehof, a neuroscientist, studied twenty years of research before she wrote The Biology of Violence. Specifically, she asks whether violence is the result of genes or a product of the environment. Aware that our culture has developed a resistance to blaming the body, she nevertheless offers proof that at times such is the case—yet the environment gets its share of the credit, too. In her opinion, each factor modifies the other such that processing a situation toward the end of a violent resolution is unique to each individual. In other words, a particular type of stimulation or overload in the brain is not necessarily going to cause violence in every instance.

“The biggest lesson we have learned from brain research,” she says, “is that violence is the result of a developmental process, a lifelong interaction between the brain and the environment.”

The way this works is that the brain keeps track of our experiences through chemical codes. When we have an interaction with a new person, we approach it with a neurochemical profile influenced by attitudes that we’ve developed over the years about whether or not the world is safe, whether people are trustworthy, and whether we can trust our instincts in reading a stranger.

However we feel about these things sets off certain emotional reactions and the chemistry of those feelings is translated into our responses. “Then that person reacts to us, and our emotional response to their reaction also changes brain chemistry a little bit. So after every interaction, we update our neurochemical profile of the world.”

The chemistry of aggression is associated with the chemistry of our attitudes and we may turn a normally appropriate response into an inappropriate response by overreaction or by directing it to the wrong person. In other words, the person’s ability to properly evaluate the situation becomes impaired. “If a person has come to believe that the world is against them, and they are overreacting to every little provocation, these violent reactions get beyond their ability to control, because they are in survival mode.”

Niehoff says that there are different patterns of violent behavior and certain physiological differences are associated with each pattern. For example:

- Over-reactive patterns – they are hyperactive with a short attention span. The challenge is to get them to slow down and engage conscious thinking processes.

- Under-reactive pattern – they have trouble developing empathy; have lower galvanic skin responses and a lower metabolic rate; and fail to attach emotion to their behavior. The challenge is to keep them connected and to reinforce their learning of appropriate social behaviors.

Applying this idea to bullying, which has been at the heart of much of the school violence in the past few years, Niehoff says “Your child is spending several hours almost every day in that environment, and to be on the receiving end of violence on a daily basis is very destructive. I think that schools need to be more aware of the subtle bullying that goes on. We’re not going to stop all aggression between kids, but we ought to be more aware of the tormenting, teasing, badgering, and threatening – and should step in early to intervene.”

Around 30 percent of school children are involved in bullying incidents. Each time a bully acts aggressively, it affects the victim’s brain chemistry and reinforces the idea that the world isn’t safe. The resulting physiological response is to protect oneself and become hyper-alert to threat. The bully, too, gets reinforced in physiological aggression, especially against kids who are isolated. Yet the more they get picked on, the more isolated they get, triggering yet another cycle of bullying.

It’s important to understand that violence has no single cause and should not be treated as if it does. It can arise from any of a number of parts of the physiological structure. Everything we encounter or experience has the potential to affect us, and there is no single factor to target for blame. Violence is the result of a complex feedback loop, but it’s one that can be broken.

Essentially, says Niehoff, the past informs the present but does not have to predict the future. “Biology is not destiny.” The brain is flexible and can relearn patterns by integrating new experiences. We have the tools to reduce violence by creating a safe and caring environment.

What about Girls?

In Clearfield, Pennsylvania in 1998, Jessica Holtmeyer, 16, made plans with a gang of friends to run away to Florida. They decided on a night and had a sleepover. They also invited Kimberly Dotts, 15, who was learning-disabled and badly wanted to be friends with this group. As they discussed their plans out in the woods, they began to get paranoid that Kimberly would snitch on them after they left. While five kids watched, Jessica and a boy named Aaron Straw put a noose over Kimberly’s neck and slung the other end over a tree branch. Then they yanked the rope, pulling on it until Kimberly’s convulsing body went limp. They let her go, but then hanged her again. When they lowered her to the ground, she was still gasping for breath, so Jessica grabbed a large rock to finish her off. Then she laughed and said that she wanted to cut the dead girl into pieces and take a finger as a souvenir.

Straw claimed that he thought they were just trying to scare her, and for the first time he saw something in Jessica that disturbed him: “It was like a side of her I didn’t see before. Like she didn’t care about nothing.

While such episodes do occur, and girls who participate can be just as callous and brutal as boys, it’s nevertheless true that only ten to fifteen percent of murders involve females of any age, and most are adults. Among the reasons girls give for killing are revenge against an abuser, self-protection, or to get rid of a witness to another crime. Few are senseless, and girls rarely kill strangers. Mostly they turn on a family member and often it’s their own child. It’s also clear that girls rarely commit a murder on their own. Often they have accomplices or do it as part of a gang.

No one is born to be violent, but males have a greater capacity to move in that direction. Antisocial acts are three times more common among males, and males have a greater tendency to develop violence-based sexual fantasies that then affect their physiology. Nevertheless, it’s not all about hormones, as many people believe. The more complex a species is, the less of a factor hormones are in violent aggression. In apes and humans, testosterone levels appear to have more to do with the desire to win than the desire to fight or to kill. It’s a quest for advancement, and it also provides males with a greater sensitivity to the environment. They can match key features with specific responses, and the brain records their successes and failures. “Testosterone was most clearly linked to aggression,” Niehoff says about one study, “when the violent behavior was a reaction to an overture perceived as a threat.” Boys with higher levels were more irritable and more easily provoked, but they did not have a greater tendency to initiate violence.

Thus, there is clearly a difference between male and female physiology, but perception and experience do play a large part in the formation of violence in either gender.

What about Thrill-killing?

While most violence occurs under provocation of some type, there is a population that initiates it for pleasure and erotic stimulation. Some are psychotic, some are provoked by substances, and some use violence as a weapon—and are most likely to turn to it after suffering a humiliating defeat. However, there are some killers for whom violence is the only way to satisfy their lust. They’re driven by the need for this form of arousal.

Yet even for them, the development of these behaviors derives from a cumulative exchange between their experiences and the nervous system. It all gets coded into the body’s neurochemistry as a sort of emotional record. The more they succeed and feel the high, the more likely it is that they will return to this behavior.

So how does all of this translate into a practical program for determining when a kid might become violent? What signs should we be looking for?

It’s clear that children who grow up around violence are at risk for pathological development. Infants and toddlers need to develop trust and a feeling of safety in order to have a healthy development. If they don’t have good relationships in the home, they will have a harder time outside the home.

Then during the school years, children develop the social skills they need to function as adults. Violence hinders this.

- Lack of safety harms cognitive functioning

- Children who live in fear often repress their feelings, which hinders their ability to empathize

- Children exposed to violence have a difficult time concentrating

- Feelings of helplessness pervade the lives of those who are abused

- Constant stress in the environment produces symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

There is a relationship between certain factors and the risk of future violence among adolescents:

- Past violent behavior

- Substance abuse

- Aggressive peers

- Family aggression

- Social stress

- Character or mental disorders

- Access to weapons

- Focused anger

- Low degree of resilience

During the first three to nine months, an infant develops bonds with the parent. Some infants are easy, some difficult. Parents must deepen this bond, because a strong factor in the development of antisocial behavior is the child’s lack of connection with others.

Self-worth, resilience, hope, intelligence, and empathy are essential to building character for effective impulse control, anger management, and conflict resolution. Without these skills, children cannot establish rewarding relationships with community systems.

While a born psychopath may have neurological disorders that defy every treatment, it still seems to be the case that many criminals with certain psychopathic traits may be turned toward something pro-social with the right nurturing.

Kids who kill to solve their problems solve nothing. Society needs to grasp the fact that children can form intent to kill, whether or not they understand what they’re doing. They can kill without knowing that it’s final, so they need to be taught what it means on television and in videogames to take the life of another person. Any signs of lack of empathy or value of another person’s life needs to be caught early and treated, not ignored. Through programming, we’re teaching kids to kill with accuracy and to think of killing as an appropriate means to an end. Since it’s unlikely that the programming will change significantly (because violence sells), we need to attend better to the danger signs and to get intervention.

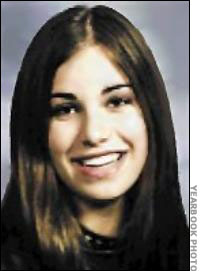

Jason Sweeney, 16, had a new girlfriend—his first. On May 30, 2003, he was on his way to see her. They had been together just two weeks and he planned to bring her over to meet his family the next day. He could hardly have been more excited, and his mother was so pleased for him. Justina Morley, 15, was about to graduate from her eighth grade class at Holy Name of Jesus grammar school. She was a pretty, dark-haired girl from a good family and with a lot of friends. This was a positive turn in Jason’s life, in line with his ambition to join the Navy the following year and become a Navy SEAL.

He left his home in Philadelphia’s blue-collar neighborhood known as Fishtown, according to The Philadelphia Inquirer, at about 4 that afternoon. He told his parents he was going on a date. He had money from his recently cashed paycheck and he was eager to spend it on her. Yet he might have been surprised when Justina invited him to go with her into an isolated, weedy industrial area off Beach Street, known as “the Trails.” It was a stone’s throw from the Delaware River, near I-95.

Much of what follows was taken from confessions afterward, and the case has not yet gone to trial.

As they walked along the gravel path, Morley’s cell phone rang. She allegedly answered with an angry retort: “What did you do, bitch out?”

Jason did not know what that was about, but he didn’t say anything. He didn’t realize it was about him. Something had gone wrong that was quickly righted.

Justina reportedly suggested they have sex and she began taking off her clothes, urging Jason to do the same. A teenage boy enamored of his first girlfriend, he wasn’t about to turn her down. He removed his shoes and began to undo his pants. Once he was in a vulnerable position, he looked up to see his best friend and two other boys he knew running at him. They were kids his mother had asked him to stay away from. He didn’t know what they had in mind, but he struggled to pull up his pants and run.

Coming at him was Edward “Eddie” Batzig, also 16 and an honor student, who had been friends with Jason since the fourth grade. They had recently been to Florida together and had vacationed with each other’s families. Following him were two brothers, Dominic Coia, 17, and Nicolas Coia, 16, known around the neighborhood as petty thieves and mischief-makers. They often wore black.

As Morley looked on, doing nothing to intervene or get help, Eddie Batzig lifted a hatchet and struck the first blow to Jason’s head. He struck as hard as he could, four or five times. Dominic Coia hit Jason in alternating blows with a hammer, slamming so hard that the hammer stuck in Jason’s skull, and the younger Coia beat him with a brick he’d picked up in the trash-strewn area.

“Blood was spurting,” Dominic later recalled. “We just kept hitting and hitting him.” Supposedly, Dominic did not believe they were really going to do it, that it was just a game, but once Eddie struck the first blow, they all stepped in.

Even as Jason was fending off blows and begging for his life, he realized this had been a trap. His “girlfriend” had played him for a fool. His last words, according to confessions, were, “I’m bleeding,” and then to Morley he said, “You set me up.”

It’s possible that Justina had known that Jason would have money from his construction job with his father, because the boys later said they had plotted the attack for more than a week, discussing how they would kill him and spend his money. For several hours that day as they waited, they listened to the Beatles’ song “Helter Skelter” over and over, more than 40 times through. This was the song that had inspired Charles Manson to send his “family” on a murderous rampage in 1969 against actress Sharon Tate and her friends on one night, and against the LaBianca couple on another. They wrote “Helter Skelter” in blood on a wall.

The boys had then donned latex gloves and two of them grabbed weapons. All three headed out to the Trails.

They kept beating Jason, ignoring his screams, until he choked on his own blood. One of them finished the job, using a large rock to crush Jason’s skull. Their clothes were covered in blood, but their minds were elsewhere. Once they knew he was dead, they rifled his pockets for the money and got $500—his cashed paycheck. Excited, they joined together in a group hug. “It was like we were happy with what we did,” Dominic said later.

They left Jason where he lay and went to the home of a friend.

When Eddie did not come home on Saturday, his mother started making calls. Justina agreed to help her search for him, although she clearly knew where he was. This woman would later say that Eddie had told her that Justina was not Jason’s girlfriend but was involved with all the boys.

At about 2 on Saturday afternoon, a group of children on mountain bikes going through the Trails came across Jason’s body and called the police. There was no ID on him and he was reported as one of five bodies found over the weekend in Philadelphia. According to Deputy Medical Examiner Ian Hood, speaking to The Philadelphia Inquirer, the autopsy indicated that the victim’s head had been crushed with multiple powerful blows. Every bone in his face was broken, except for the left cheekbone, and he was unrecognizable. Pieces of bone were lodged in his brain. His head was so chopped up, Hood said, his skull could be considered split in two.

The police learned that Jason’s father had reported him missing, having last seen him on Friday afternoon. They brought him to the morgue. In astonishment, he identified the body on Monday morning as his son. Jason had never been involved in drugs or gangs like other boys in that blue-collar town, Paul Sweeney said. How could this happen?

Since Jason had been on his way to Justina’s, the police checked there and also learned from witnesses that the Coia brothers and Eddie Batzig knew him and had been with him recently. When they requested that the boys come to the police station as possible witnesses, two of them soon became suspects and they quickly confessed to the murder. Under further questioning, Batzig and one of the Coias talked about the crime but apparently expressed no remorse. According to detectives’ statements to reporters, Eddie and Dominic gave statements and seemed only interested in when they could return home. As the story came out, Justina was brought into custody, but she made no statements. Neither did Nicholas. All of them acquired legal counsel.

According to a police transcript made available to the paper, Dominic admitted under questioning that Justina Morley had been the bait to get Sweeney to the area. “We took Sweeney’s wallet,” he said, “and we split up the money and partied beyond redemption.”

He wasn’t far wrong. He and the other boys, charged in Common Pleas Court as adults with first-degree murder, conspiracy and related charges, could now face the death penalty. Their friend 18-year-old Joshua Staab testified that he had overheard their plans and had helped to wash out their bloody clothing afterward (as did an unnamed 16-year-old girl). He knew they were planning to kill Jason. They went out that evening, he said, and returned after failing to meet up with Justina as planned. They called her and then went out again. Twenty minutes later they were back, but now in blood-covered clothes, telling Staab that they had killed Jason and could not believe that they had done it.

“They were shaking,” Staab added in court, in a way that implied they were exhilarated. They divided the money at the kitchen table. Each now had $125, and Morley appeared to him to be happy about that. According to Staab, she had called the whole incident “a rush.” Staab noticed no signs in any of them of anxiety or remorse. “They seemed pretty fine.” The ill-gotten gains were spent buying marijuana, heroin, cocaine and Xanax. Even deodorant.

In court, as recorded in local newspapers, although Morley shed a few tears, she also snickered with her co-defendants during one sidebar. Eddie kept his eyes on the floor while Dominic appeared agitated.

While there was some speculation that they had been high at the time, Dominic Coia denied it. “I was as sober as I am now,” the report quotes him as saying, and then he added, “It is sick, isn’t it?”

“Shocking beyond words,” Assistant DA Jude Conroy later remarked.

At their hearing, Judge Seamus McCaffery noted the barbaric nature of the violence, questioning any civilization that produces such callous depravity.

Morley’s case was pending, due to a possible mitigating circumstance of depression. At age 15, she is too young for the death penalty. Her lawyer indicated that during their conversations she had never referred to Jason as her boyfriend and it is his contention that there is no evidence that she knew anything about this attack or was involved. He wanted her case separated from that of the boys.

Verdicts in the cases have been reached. The boys were all found guilty, and Morley was allowed to plead down to third degree murder, due to a deal reached between her lawyer and the prosecution.

Jason’s grieving mother believed the killing could only have been about getting a thrill, because her son was generous. If they had asked, she commented, he would have given them the money. He always gave things away. Considering the group hug afterward and their reported state of mind after the alleged attack, she may be correct. The police indicated that if all they wanted was the money, they could have knocked him out and taken it.

Studies show that while youth violence appears to have declined, those statistics center only on actual arrests, not on violent acts that might have ended a life but did not. “More than 400,000 youths aged ten to nineteen were injured as a result of violence in 2000,” says one report, “and 15 to 30 % of adolescent girls admit to committing a serious violent act.” More and more kids are getting involved in risky behavior, searching for thrills and feeling less ashamed of harm done to others.

While there is always talk about drugs as the cause, or violence in the media, negligent parents, and a society lax in its own values, it’s also clear that these kids made choices in full awareness that they would be committing not just murder but an egregious betrayal of a friend. This gives the crime an added layer of brutality.

*****

This account was developed from numerous articles in newspapers local to the Philadelphia area, notably The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Classes had already begun that morning of February 3, 2004, when three boys entered a restroom on the second floor of the Southwood Middle School in the prosperous Palmetto section of Miami-Dade County. Michael Hernandez, who had just turned fourteen the day before, tried to lure one of the other two into a stall, but that boy refused to go in. The second one, Jaime Rodrigo Gough, also 14, was curious to see what was in the stall, so he entered it. He had no inkling of what Hernandez, his best friend since the seventh grade, had to show him.

It turned out to be a knife, and that was the last thing Gough saw.

When another boy entered the bathroom moments later, he saw Hernandez washing his hands and a bloody stall in which two feet were dangling. He asked Hernandez, “Do you see that?” and Hernandez acknowledged that he had, adding that they should notify a security guard. The other boy ran out to do so, but Hernandez was not behind him. When the guard did not immediately respond, the boy went back in. What he saw shocked him.

Jaime Gough, a shy honor student often bullied, lay over the toilet seat, bleeding profusely from a wound to this throat. He also had multiple stab wounds, but he appeared to still be alive. The security guard arrived, but Hernandez was nowhere to be found. He’d slipped away to the computer lab, apparently oblivious to the blood spatter on his clothing and shoes. The boy from the restroom told his story and officials went looking for Hernandez.

When the rescue unit arrived and went into the restroom, they were unable to save Gough, who was pronounced dead at the scene.

The school was quickly locked down, with students kept in their classrooms most of the day and anxious parents gathering outside. The county medical examiner’s office removed the body and the police notified Gough’s family. They were stunned. This was an affluent school for artistically gifted children. Jaime was a musician, athlete and straight-A student. He had never been in trouble. Jaime’s mother collapsed and had to be briefly hospitalized.

The police pulled Hernandez from class to question him. A search of his book bag produced a jacket and latex glove with blood on them, as well as a serrated folding knife, which looked to be the murder weapon. They read him his rights, made sure he understood, and took him for questioning.

After several hours, he confessed to the crime, waiving his right to appear in juvenile court. He was charged with first-degree murder, which meant that he would be tried as an adult, and held in secure detention. He was faced with life in prison, so his parents hired attorney Richard Rosenbaum, who was experienced in juvenile crimes and who believed that no child should be abandoned to the prison system. Rosenbaum had won a lesser sentence and a release for Lionel Tate, a twelve-year-old who had murdered his six-year-old neighbor and been sentenced to life.

Students at Southwood who commented about the murder in their midst said that Hernandez and Gough had been the best of friends and neither had ever been in trouble. Hernandez was known to be respectful, even “nice.” He clearly had a darker side that no one knew, not even his family. While at first it seemed as if this might be just an unfortunate incident between friends that had somehow turned tragic, as the case unfolded, the discoveries proved to be shocking.

Michael Hernandez was a troubled boy. According to AP reports, he kept a personal journal in which he wrote about his ambitions, which included committing mass murder. Apparently, even as he avidly read the Bible he was fixated on violence. Forty-one pages of his doodlings were released by the state attorney general’s office in March and printed in the Miami Herald. Initially, they withheld two pages in which Hernandez had outlined his killing plan, but eventually these came out as well. So did portions of Hernandez’ videotaped confession to the police, which showed him to be calm as he talked and rather cold.

It seems that Hernandez had devised for himself a little birthday celebration. He had a list of three people that he had planned to kill: his older sister, a long-time friend referred to in the reports as “A.D.M.,” and Gough. (According to the earliest reports, he’d apparently targeted another boy as well, who was not on this list, but when that student did not show up on his birthday or the next day, Hernandez turned on Gough.)

Hernandez intended to kill his two friends at school, he indicated, and prop their corpses up on toilets. In preparation, he had gotten a knife from his father’s store, gloves, a hat, a jacket, and tape. He made instructions to himself to be “quick” and to “remove all blood.” Also to “Make sure they are dead Make sure there is no one in the bathrooms If so Kill Them.”

His ploy that day was to lure the first boy into a stall, strangle him with a belt and then stab him in the back. “And that would have been it,” he told police. But A.D.M. had not gone along with it. Exactly when he left the bathroom in which Hernandez was attacking Gough remained unclear, although the boy who brought the security guard had noticed a student exiting whom he did not know.

In his journals, Hernandez had a six-page Internet printout about mass, spree, and serial murderers on which he had drawn a hanged man and had written “will become a serial killer.” (AP clarifications later indicated that he might have been finishing a sentence that was cut off in the copying process, rather than spelling out his intentions, though in other writings, it’s clear that he hopes to become a murderer.) He also had written a list of violent videogames and movies, had instructions for making a bomb, and made a Swastika image with the words “White Power”. Oddly, another note said, “You will be a serial killer and mass murderer, stay along, never forget God ever, have a cult and plan mass kidnapping for new world… be an expert thief.” In addition, he had drawn a figure being prepared for death by a suspended blade.

Forensic psychologist and child psychology specialist Dr. Leonard Haber told the Miami Herald that the writings were “cold, calculated, and demonic.” A defense psychologist mentioned that Hernandez was a complex young man. Indeed, the boy murderer had written to himself that once he had succeeded with his diabolical plan, he was to “thank God for success first.”

A neighbor who had driven Hernandez to school that day said that nothing about him seemed out of the ordinary. They talked about music and his plans for the day. She could never have guessed what he had in mind, or had in his bag. Within moments of leaving her car, Hernandez had used the knife to stab his friend.

Circuit Judge Henry Leyte-Vidal asked both sides to find psychologists to assess Hernandez for competency. When Hernandez came to court, his head was shaved.

In one new report, defense attorney Rosenbaum was quoted as saying, “The psychological evidence, I think, will be overwhelming.”

As of this writing, that remains to be seen.

For this school year, Gough’s murder brought the total number of deaths on school grounds to 35, more than the total for the previous two years combined.

The consensus in court was that Stuart Harling was not ill but stupid in his possible bid to become his town’s first serial killer. If they’re right, then the sentence he received means he could be free one day to consider doing it again.

As the sensational trial commenced in June, several British media sources published the daily details. Harling, 19 and an unemployed accountant trainee, had gone out on April 6, 2006, prepared to kill. In fact, he’d rehearsed for it and had spent a year in preparation. Dressed in a long wig and sunglasses that day, and armed with a large hunting knife (all of which he’d purchased online), he went to the wooded grounds of St. George’s Hospital in Hornchurch, Essex, and hid behind a hedgeFrom there Harling spotted a newly-married thirty-three-year-old nurse, Cheryl Moss, taking a cigarette break.

Cheryl was talking on her cell phone, so she did not notice the young man leap out at her the instant she ended her call. In a frenzied manner, Harling stabbed her in the head, neck, face, back, and chest. After the first thrusts, she fell to the ground, unable to fend off the blows. She couldn’t even scream, so no one came to her rescue. Harling managed to stab her 72 times until his wig fell off, at which point he fled.

Cheryl’s colleagues found her and tried to help, but she was already dead. They called the police, and it did not take the authorities long to find the culprit. For all his planning, Harling had made a significant error: he left his murder kit behind, containing the bloody knife, sunglasses, wig, gloves, and an envelope addressed to him. The police went to his home in Rainham and arrested him. By that time, he had already logged onto the Internet to see the news flashes about the murder.

Later, Harling claimed that he’d been surprised to learn from the arresting officers that his victim had died. He’d meant only to take her car keys, he said, so he could “overthrow an African government.” His friends confirmed that he’d talked about recruiting people for this venture as a way to get rich. Obviously, his plan included mitigating his crime with a mental illness defense.

Computer experts examined Harling’s hard drive and detectives pieced together a convincing portrait of a serial killer wannabe. When he’d watched and then attacked Cheryl Moss, Harling had apparently adopted the MO of one of his favorite serial killers, “Night Stalker” Richard Ramirez. He’d also recently read accounts on Wikipedia about Dennis Nilsen and Colin Ireland, both notorious British serial killers. In addition, he spent hours on Web sites devoted to weaponry, serial killers, and crime, and he immersed in extremely violent video games. He also admired Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold for killing bullies in Littleton, Colorado in 1999, and had decided that he, too, wanted to kill a succession of bullies. So how was it that no one noticed his growing penchant for violence?

Harling had dropped out of school and withdrawn from friends and family, living in his fantasies. His plan to commit murder had developed after learning combat maneuvers from a CD used to train U. S. Marines in lethal procedures. An examination of Harling’s Internet searches, in which he had entered “serial killer” and the names of various British towns, indicated that he’d aspired to become his town’s first serial murderer. With this information, the prosecutor argued that Harling had committed premeditated, cold-blooded murder.

Harling’s defense was that he had Asperger’s syndrome, which had affected his ability to understand what he was doing. This, in turn, diminished his criminal responsibility. He said that during the stabbing, he’d felt the same as if he were watching himself stab someone in a film or computer game. It had felt distant and “didn’t bother him.” In fact, he added, “It kind of ruined my day.”

A prison guard testified that Harling had said he’d committed the murder out of boredom, but Harling denied this. He corrected the account by saying he’d told the guard that if he was released, he would probably kill more people out of boredom — as if that made a difference. A defense psychiatrist who assessed Harling said, “I cannot think of a more dangerous teenager in the country. If released he will probably kill again. He’s completely detached from emotion.”

Dr. Andrew Payne, a psychiatrist for the prosecution, added another angle: he believed that Harling was hoping for media attention and that his supposed illness was just a ploy to seem like a victim.

In short, there was no doubt that Harling had committed the murder and had long prepared for it. The jury’s job was to decide if, due to a mental defect, he did not appreciate in April 2006 that murder was wrong. His constant insults and threats throughout the proceedings, aimed at the judge and prosecutor, no doubt affected their perception of him as a genuine danger.

In July 2007, the jury voted ten to one that Harling was guilty of first-degree murder. Due to the real possibility that he would become violent at sentencing, Judge Brian Barker allowed him to decline to appear. Nevertheless, Barker made a speech. While he accepted that certain autistic traits influenced Harling’s emotional detachment, he decided that the murder had nevertheless been premeditated and under Harling’s control. Viewing the young man as volatile and dangerous, Barker gave him a life sentence, with a minimum of 20 years.

In July 2007, a girl who participated in a triple homicide was convicted in Canada. Due to her age, Canadian media sources observed the Youth Criminal Justice Act and declined to reveal her name, but it has turned up in many international reports.

On April 23, 2006, in a town in southeastern Alberta called Medicine Hat, the parents and younger brother of Jasmine Richardson were discovered murdered in their home. A six-year-old friend came to the house early on Sunday afternoon, saw a body through the window, and alerted his mother, who called the authorities.

Police arrived and discovered three victims. Debra Richardson, 48, lay at the foot of the basement stairs, according to the Ottawa Citizen, covered in blood and stabbed 12 times. Her husband, Marc, was stabbed twice as many times, all over his face and torso, including his crotch. He’d bled out so much there was little left in his body, but from the spatters all over the TV room it was clear he had put up a tremendous fight. Eight-year-old Jacob was found in his bed, with his throat cut.

Detectives sent for the forensic unit to process the scene, and they brought dogs to go through the home and grounds. A white truck sat in the driveway with a smashed window, and another truck belonging to the family was found off the property. Items in the home indicated that there was a twelve-year-old daughter, Jasmine, who was missing. Police did not know if she had been abducted, so a country-wide warrant was issued for her.

Friends of Jasmine’s twenty-three-year-old boyfriend, Jeremy Allen Steinke, pointed authorities to a town in Saskatchewan, and they found Jasmine alive and with Steinke. He was an unemployed high school dropout, considered the unofficial leader of a group of Goth-punks. The two were arrested without incident and returned to Medicine Hat. After a hearing, Jasmine was sent to the Calgary Young Offenders Centre to await a trial. Within days, she had penned an apology letter to her family, admitting she had taken part in their slaughter. She wrote that she wished she could “take it all back” because now she “had no one.” She said her brother was killed because he was too sensitive to survive without her parents. She herself had choked him to make him unconscious.

Supposedly, this all occurred because the seventh-grade girl had reacted badly to being grounded for dating Steinke behind her parents’ backs. They told her she could no longer see him. Yet Jasmine had already agreed to marry Steinke and she was determined to be with him. She urged him to help her get rid of them.

A romantic bond was not all this couple shared: they had a fixation on Goth culture and Steinke even claimed to be a 300-year-old werewolf. Both had posts on a Web site known as VampireFreaks.com, and Steinke reportedly wore a vial of blood around his neck. Jasmine referred to herself on another site as “runawaydevil”. They shared an appreciation for razor blades, serial killers, vampires, and blood. They would soon learn that murder was not fantasy.

During the 2007 trial, covered by reporters from around Canada, some facts about Jasmine came out that indicated her state of mind. Not only did she and her boyfriend ascribe to the darker side of Goth culture, with a fixation on death and imaginary monsters, but they had watched the film Natural Born Killers.

Oliver Stone produced this 1994 film, which is engorged with gratuitous violence. A killing couple, Mickey (Woody Harrelson) and Mallory (Juliette Lewis), were based on spree killers Charles Starkweather and his girlfriend. Throughout the film they commit some 52 murders, including massacres with multiple victims. They start with the slaughter of Mallory’s abusive parents, one by drowning the other by burning, but spare the younger brother. One can see how an angry couple who embrace death culture and find parents an annoying hindrance might see in this film an affirmation of their bid for freedom and a violent solution.

While Jasmine’s apology letter was not read to the jury, deemed to have been gained via improper interrogation protocol, jurors did see a drawing found in Jasmine’s locker that depicted four stick figures. The middle-sized figure throws gasoline on the other three with a smile, lights them ablaze, and then runs to a vehicle labeled “Jeremy’s truck.” In addition, the two had exchanged letters after their arrest that indicated they wished they had run away together. There was no indication in these communications that Jasmine was remorseful or an unwilling accomplice. She also had stolen her mother’s ATM card that night, got money, and had sex with her lover — all pointing to a callous attitude. (Even her apology letter was largely self-pitying.)

Jasmine’s attorney, Tim Foster, accepted the idea that Jasmine might have engaged in discussions about killing her parents, but said she did not mean that she would literally do it. The scenario he painted was that Steinke had gotten high on cocaine, watched the violent movie, and undertook to rescue Jasmine, as “Mickey” had done for “Mallory. ” The idea was his alone, as was the act. Thus, Jasmine, too, was a victim.

She took the stand in her own defense and affirmed that her boyfriend was the killer. She cried when asked about choking and stabbing her brother and said that Steinke had made her do it, as her brother begged for his life. She had a knife in her hand, she said, for self-defense, but Steinke had taken it and slit her brother’s throat.

While the prosecutor conceded that Jasmine did not engage in the act of murder, she had persuaded and encouraged Steinke to do it, telling him which window would be unlocked for entering the home on Saturday night. She also willingly fled with him. Thus, she was eligible for a murder conviction. He urged the jury to remember her part.

On July 9, 2007, after the jury deliberated just over four hours, Jasmine was convicted of three counts of first-degree murder. She began to weep, according to the Edmonton Sun. Under Canadian law, she cannot receive an adult sentence, so she faced a maximum of six years in prison and four of probation. Steinke faces trial for murder next year; he has not yet entered a plea.

Jasmine Richardson is the youngest person to be convicted of multiple murder in Canadian history. For that matter, she’s the youngest in North American history.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (4th ed.). Washington, D C, American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

Beren, P. (Ed.). (1998). Narcissistic Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Black, D. W. Bad Boys, Bad Men: Confronting Antisocial Personality Disorder. London: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Brandt, J. R., Kennedy, W. A., Patrcik, C. J., & Curtin, J. J. (1997) Assessment of psychopathy in a population of incarcerated adolescent offenders. Psychological Assessment, 9, 429-435.

Brown, R. A. (1999). Assessing attitudes and behaviors of high-risk adolescents: An evaluation of the self-report method. Adolescence, 34, 25-46.

Christian, R. E., Frick P. J., Hill, N. L., & Tyler, L. (1997) Psychopathy and conduct problems in children: Implications for subtyping children with conduct problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 233-241.

Daderman, A. M. (1999). Differences between severely conduct disordered juvenile males and normal juvenile males: The study of personality traits. Personality & Individual Differences, 26, 827-845.

Disturbed Children: Assessment Through Team Process (1995) Kansas: The Menninger Clinic.

Eddy, J. M. Conduct Disorders. Kansas City, MO: Compact Clinicals, 1996.

Ewing, C. P. Kids Who Kill. New York: Avon, 1990.

Friedlander, K. (1945). Formation of the antisocial character. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 1, 189-203.

Garbarino, J. Lost Boys: Why Our Sons Turn Violent. New York: Free Press, 1999.

Grossman, Dave. On Killing. New York: Little Brown, 1995.

Grossman, Dave & Gloria DeGaetano. Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill. New York: Crown, 1999.

Heide, K. Young Killers: The Challenge of Juvenile Homicide. New York: Sage, 1998.

Hoge, R. D. & Andrews, D. A. Assessing the Youthful Offender: Issues and Techniques. New York: Plenum, 1996.

Howell, A. J., Reddon, J. R., & Enns, R. A. ( 1997). Immediate antecedents to adolescent offenses. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 355-360.

Kelleher, M. When Good Kids Kill. New York: Praeger, 1998.

Lassiter, D. Killer Kids. New York: Pinnacle, 1998.

Leyton, Elliott. Sole Survivor: Children Who Murder Their Families. New York: Pocket, 1990.

Lindecker, Clifford. Killer Kids. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

Loeber, R. (1990). Development and risk factors of juvenile antisocial behavior and delinquency. Clinical Psychology Review, 10, 1-41.

Lynam, D. R. (1996). Early Identification of Chronic Offenders: Who is the fledgling psychopath? Psychological Bulletin, 120, 209-224.

Magid, K. & McKelvey, C. A. High Risk: Children Without a Conscience. New York: Bantam, 1987.

Morrison, Blake. As If: A Crime, A Trial, A Question of Childhood. New York, Picador, 1997.

Munger, R. L. The Ecology of Troubled Children. New York: Brookline Books, 1998.

Niehoff, Debra. The Biology of Violence. New York: Free Press, 1999.

Pressman, S. D. and R. Pressman. The Narcissistic Family: Diagnosis and Treatment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994.

Robins, L. N. (1991). “Conduct Disorder, ” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 20, 566-680.

Rogers, R., Johansen, J, Chang, J. J. & Salekin, R. T. (1997). Predictors of adolescent psychopathy: Oppositional and conduct-disordered symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 25, 261-271.

Rutter, M., Giller, H., & Hagell, A. Antisocial Behavior by Young People. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Rygaard, N. P. (1998). “Psychopathic children: Indicators of organic dysfunction,” In T. Millon, E. Simonsen, M. Biket-Smith, R. D. Davis (Eds.) Psychopathy: Antisocial, Criminal and Violent Behavior. New York: Guilford Press. (247-259).

Schecter, Harold. Fiend: The Shocking True Story of America’s Youngest Serial Killer. New York, Pocket, 2000.

Sells, S. P. Treating the Tough Adolescent. Behavioral Science Books, 1998.