Women Who Kill: Part Two — Savage Mistress — Crime Library

Just because a female killer gets only local media coverage, it doesn’t mean that her crimes are not worthy of the national news. Compared to their male counterparts, a number of women who have killed in weird or vicious ways are barely known outside their hometowns.

In New Orleans, the ghost tours always stop at a particular mansion in the midst of the French Quarter, on the corner of Royal and Governor Nicholls Streets. The house had once been owned by socialites, a physician by the name of Lalaurie and his wife, Delphine. They seemed a respectable pair with their two children, and the whole town gossiped about their lavish cocktail parties and obedient slaves.

Little did people know what Madame Lalaurie did to make her servants so submissive, although she had been fined in court several times for her misconduct. Once she was charged in the death of a child, whom she had beaten so savagely with a whip that the girl had jumped out a third-floor window. Yet it was not until after a fire broke out in the home in April of 1834 that the full tale came out, and it proved to be worse than anyone could have imagined.

Katherine Smith documents it from newspaper articles for her book, Journey into Darkness. A native of New Orleans and a folklore historian, she has heard the legends and looked into the facts behind the tales. Despite the exaggerations inevitable with folklore, the facts are still horrendous.

It was April 10 and the Lalauries were entertaining their guests. The fire started in the kitchen and the fire brigade went through the courtyard to put it out. They heard screams and moans from a room on the third floor, so they went to investigate. Since the door to the room was locked, the firemen rammed it open.

At once they smelled the unmistakable odor of death and some of them vomited. Yet it wasn’t just the dead slaves chained to the walls that got their attention, but the living ones, who were only barely alive. One woman was so startled by their entrance that she fled toward a window and jumped.

Most of the victims had been severely maimed by medical experiments. Some were even strapped to tables. One man had been surgically transformed into a woman, and a woman looked like a human crab. Her arm and leg bones had been broken and reset into odd angles, and she was kept in a small cage. Another woman’s arms had been amputated and her skin was peeled off in an odd sort of spiral pattern. Author Victor Klein, also a New Orleans native, indicates that scattered around the room were pails full of body parts, organs, and severed heads. Among those who had died were males whose faces had been grotesquely disfigured.

The survivors were quickly removed for medical attention, and as word spread, a lynch mob formed outside the home. However, the Lalauries had escaped to another part of Louisiana and were never brought to justice.

While many people view it all as the work of Madame herself, it’s fairly clear that her husband was in on it, too. Like many women, she was part of a killing team. Sometimes for a woman to start killing, she requires the peculiar chemistry ignited by the brazenness of a sadist or psychopath. The history of crime gives us numerous examples.

Karla Homolka cried at her trial, as Terry Manners depicted in Deadlier than the Male. She and her husband, the notorious Paul Bernardo (aka Teale), had killed three girls, including Karla’s own sister. It was Karla who had drugged young Tammy before Christmas in 1990 so Paul could rape her. They made a videotape of these activities so they could relive the pleasure of torturing another human being at their mercy. To their surprise, Tammy vomited and then suffocated and died. Karla and Paul kept their dark secret to themselves.

Karla was 17 when she met Paul Bernardo, 23. To neighbors they seemed the perfect couple — they’d even been nicknamed Ken and Barbie — but behind closed doors they dreamed up and carried out atrocities that boggled even the minds of the lawyers who later defended them. Karla was a simple, middle-class girl, but she had been attracted to Paul and his sadistic ways from the moment they met. Stephen Williams describes her coy submission in Invisible Darkness, indicating that she let Paul do anything he desired with her, and his demands became increasingly brutal. Nevertheless, she wrote notes telling him she was ready for anything and wanted more. He liked being in control, and with him Karla felt at peace. They married in 1991 at Niagara Falls, just two weeks after Paul had killed another girl.

She was 14-year-old Leslie Mahaffy, who was found on Karla and Paul’s wedding day near a Toronto suburb, dismembered and cemented into seven blocks of concrete submerged in a lake. Then Kristen French disappeared in 1992. She was seen being forced into a car in the middle of the day while walking home from school. Then weeks later she was found murdered, her long brown hair hacked off.

Karla had lured Kristen toward the car because Paul liked young girls and that way she could keep him happy. Before killing her, they kept Kristen captive for their pleasure, and then Karla had to dress the part of a schoolgirl just like Kristen so Paul could have sex with her.

Karla was the one who turned Paul in. After he had brutally beaten her with a flashlight and she called the police, he had locked her out of the house.

Around this time, Paul was identified through DNA as the Scarborough Rapist, at work in the Toronto area brutalizing women since 1988. Two police forces, armed with details from Karla, converged on him and arrested him. They found the incriminating videotapes and charged him with forty-two criminal counts.

For her cooperation and a plea of guilty to two counts of manslaughter, Karla was sentenced to only two 12-year terms, to be served concurrently, and she was never again to own any firearms, explosives or ammunition. She went to prison and then came back to court to testify against Paul, from whom she had sought and gained a divorce.

At her parole hearing in 1997, it was determined that she was still too potentially violent to be allowed into society. The same was true as of February 2001, and it’s likely that Karla will serve her entire term until 2005. Even though some people believed that she was coerced into what she did by her overbearing husband, many others feel just as certain that she was as much a part of it as he was and that she enjoyed it. That she could kill her sister and then continue to participate in more rapes and murders for several years indicates a deviant personality.

Karla and Paul are not alone. In fact, Michael Newton states in The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers that around 25% of all serial killers are male-female teams, including the likes of Bonnie and Clyde, Charles Starkweather and Caril Fugate, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, Fred and Rose West, Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez, Doug Clark and Carol Bundy, and Gerald and Charlene Gallego. Each of these couples involved a male and female who together lured and savaged innocent victims, including children. Sometimes the female ratted on the male, and sometimes they were just caught. While few studies have been done on the kind of chemistry that happens between two people that sets off a rape or killing spree, many experts believe that under other circumstances and with another man, the female might not have been as sadistic or cold-blooded. (Yet in some cases, the female was the dominant or encouraging partner.)

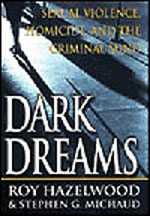

Former FBI Special Agent Roy Hazelwood, an expert on sexual sadists and author of Dark Dreams, believes that couples like Karla and Paul are not like the team killers Bonnie and Clyde. “Let’s take Bonnie and Clyde, or Susan Smith in South Carolina who murdered her kids to gain access to a male,” he says. “Wives and girlfriends of sexual sadists are quite different. I interviewed 20 women, and four of them had participated in the murder of another person. You can’t excuse that. They are legally, morally, and ethically responsible for what they’ve done. But I believe the man had reshaped their sexual norms.” After having spoken to these women, he tended to see them as compliant accomplices with weak self-esteem who had been isolated and made to believe that the man in their lives was the center of the universe. They had to do what he wanted or their world would fall apart.

Roy Hazelwood

Yet those psychiatrists who have evaluated Karla Homolka — or Karla Teale, as she is now known — believe that even without Paul, she has the propensity for irresponsibility and violence against others that make them fear her release. They don’t think it’s just “team chemistry,” they think it’s something about Karla. The families of her victims are relieved to know that she will remain in prison for a while longer.

Another woman similar to Karla, who could not be confused with a compliant accomplice, is Judith Ann Neelley. At age 15, she married Alvin Neelley, and the next year, 1980, she robbed a woman at gunpoint. Together they thought of themselves as outlaws, ‘Boney and Claude,’ and turned from theft to random violence. They lured a 13-year-old girl into their car and in front of their own children, they molested her and then killed the girl. Judith injected her with liquid drain cleaner and then shot her. She also shot a man who survived the attack and fingered her, and killed his girlfriend. When this team was arrested, Alvin claimed that Judith had instigated the crimes, being responsible for eight murders, and he had just gone along with her. She liked to have power over others, he said.

Yet when Judith was arrested, she blamed Alvin and said she was a victim of domestic abuse. She tried to claim she was insane and could not help what she had done. While the jury convicted her of murder in 1983, they gave her life. The judge then sentenced her to death, but after an appeal, her sentence was commuted in 1999 to life in prison. A kidnap victim later said that Judith was the one with the gun, and that she had bragged of numerous murders, but no evidence ever linked her to any unsolved cases. Nevertheless, she clearly had a thirst for violence and power. That she was young and attractive gave her an advantage, in that many people feel that women are not — and cannot be — as dangerous as men. She was just a girl, after all. Yet let’s have a look at the facts about female serial killers.

Dorothea Puente ran a boarding house in Sacramento, California, and loved tending her garden. She was quick to help those down on their luck, and during the 1980s, this 59-year-old woman opened her home to welfare and social security recipients. She offered low rent and hot meals, but the turnover was high. When neighbors inquired about someone they hadn’t seen in a while, she would tell them that so-and-so had simply moved on. Yet the government checks kept coming and getting cashed, so a social worker went to check on a client reported missing. She heard about the bad smells coming from the house and felt sure her client wouldn’t just run away, so she notified police. Upon investigating, the police dug up the lawns and gardens and soon discovered the source of the stench. There were seven bodies covered in lime and plastic, one of which had been beheaded and dismembered. Autopsies later confirmed that these people had died by drug overdoses.

In the meantime, Puente had fooled the police with her grandmotherly ways and had skipped town, but an elderly man that she tried to pick up in a bar recognized her as the hunted fugitive. When arrested, she said, “Did you know I used to be a very good person once?” It turned out that she had forged signatures on over 60 checks and had served prison time even before all of this for theft and fraud. Upon release, she had even been considered a danger to the elderly.

and Their Victims

Puente was tried for nine murders — two bodies being found elsewhere — but convicted of three because one male juror refused to agree to anything more. She got life in prison.

How a man could decide that Puente had murdered three people found buried in her garden but not all seven is at the heart of how the American public views female killers. There’s a pervasive sense that women — especially elderly women — just cannot be that dangerous. While males acquire such aggressive monikers as Jack the Ripper and the Southside Slasher, women get the more passive-sounding Damsel of Doom, Angel-Maker, or Giggling Granny. Media stereotypes help to form the impression that women are less lethal than men.

However, statistics say otherwise. Just because someone might choose poison as a weapon over a knife or gun does not make her victims any less dead. Although Aileen Wuornos was designated a “rare female serial killer,” her rarity was that she used a gun to kill strangers, which is not generally the female’s weapon of choice. However, it’s a mistake to think that just because they’re not acting like males, few women have been serial killers.

In Serial Murderers and Their Victims, Hickey examines the cases of 62 female serial killers, which is only a sample and not an exhaustive list. They represented 16% of the killers in his study, and collectively had murdered from 400 to 600 people. More than nine out of ten were white, and two-thirds acted alone. Many were “black widows,” or health-care providers, and they tended to be older and to get away with their crimes for a longer period of time than did their male counterparts. One had been killing for 34 years. Those who killed with male partners were more likely to be violent than those who acted alone, where poisoning was preferred. Their average number of victims was seven to nine and most of them had no prior criminal records.

According to Deborah Schurman-Kauflin in The New Predator, most of these women had a history of cruelty toward animals and levels of isolation that fed self-absorbed fantasies. The sources of their violence include attachment disorders, abandonment, harsh discipline, and abuse, but a few have been stone-cold psychopaths. Some have even gotten others to kill for them so they could get what they wanted without being caught and incarcerated. Let’s take a closer look at that category.

Very little research has been done on the female antisocial personality, although books have been written and movies made about women who demonstrate all the right traits. A good example is To Die For, starring Nicole Kidman as a weather girl who manipulates a male high school student to kill her husband so she can accelerate her miniscule career. She exhibits narcissism, an extreme need for attention, grandiose ambition, a lack of attachment to others, a need to control, and an ability to exploit and even kill without accepting any responsibility. After her husband’s death, she feels no remorse and she shoos away the boy whose infatuation with her made murder possible. She’s a pure type. She’s a manipulator extraordinaire: she works her harm through others.

Ever Wanted

Not much different from her is the real-life Patricia Allanson, whom Anne Rule documented in Everything She Ever Wanted. Patricia thought of herself as special. Her parents had always bailed her out and she’d never had to take responsibility for herself. Partly because of that, she felt that her husband ought to be able to give her anything she wanted. She needed constant attention — what some men might call high maintenance — and unqualified love. She first had married an army sergeant and stayed with him long enough to have three children, but got tired of him, so she left him in 1972 to find a better quality of life — what she felt she deserved. She met Tom Allanson, six years younger than her. She had her eye on someone else, but it looked like Tom could give her whatever she wanted.

He had money and as soon as he was divorced, he was quite insistent that Pat marry him. He later recalled that he was the one who pressured her, while she would say, “You don’t want to marry me.” Yet she could just as easily have been stoking the fire by making herself unobtainable. In 1974, he married her dressed as Rhett Butler, while she played Scarlett, and gave her a heavily-mortgaged, 52-acre home in Zebulon, Georgia, that she referred to as Tara. They set about to raise Morgan horses, and even Jimmy Carter, then governor of Georgia, came to visit. Pat’s ambitions of being the proper Southern belle were being realized — or so it seemed. Ann Rule indicates that she had quite another scheme at work that would eventually involve murder.

When Walter Allanson, Tom’s father, disapproved of her and angrily tried to force Tom out of his life, Pat filed complaints of sexual harassment against him, claiming that he had exposed himself to her. Tom grew alarmed over this, along with threats that he heard that his father was going to kill him, so he took out a restraining order. Yet his father was taking a defensive stand, believing that his own son was out to kill him. Someone had stolen a pistol and rifle from his home and he was convinced it was his son. The police searched Tom’s home and came up empty-handed, yet the intense fear and anger continued to grow on both sides. With no form of communication taking place, it was the perfect set-up for a manipulative psychopath who wanted to get something for herself.

On July 29, 1974, Walter and his wife, Carolyn, were ambushed. As they took a trip in their car, someone began to shoot at them. They survived the inexplicable attack and felt sure that Tom had orchestrated it, although he was far away on that day. The situation between father and son grew more paranoid until August 3. On that day, Tom dropped Pat off at the doctor and then walked over to see his mother when he was sure his father would not be home. Pat had told him that someone had been calling their house all night long and then had just breathed. She felt sure it was Walter, so Tom felt it was time to try to straighten things out. Otherwise, he thought his father might try to shoot him off his horse in the parade that weekend. His mother was not home, although he expected her, so to avoid the possibility of running into Walter, he checked the basement door, found it unlocked, and went to sit inside and wait.

To his surprise, Walter came home — it was later determined that he’d received a call from an unknown woman telling him that Tom was at his house — and began to rant and rave over Tom’s presence. The electricity was off, so he went into the basement to look around, found the switch box tampered with, and then went out to call the police. But the phone line had been cut, so he used a neighbor’s phone to get the police out there. They arrived, but Walter said he’d take care of the situation himself, so they left. He then went back into the basement and started shooting randomly. Carolyn was home by that time and he called up to her that he had Tom cornered. He needed the gun he’d just purchased, so she grabbed it to bring it to him. Tom later claimed that he panicked, certain that his father would kill him. He could not imagine how he had gotten into such a situation.

When officers arrived once again in response to an emergency call, they found Carolyn Allanson sitting upright on the basement steps, shot dead. Through the basement window, they could see numerous sprays of blood. Not far away inside, Walter lay on the ground. He’d been shot numerous times — it was later determined that there were 20 separate entrance wounds — and the police immediately suspected Tom. He’d been seen there, and a man matching his description had run from the crime scene.

Tom was soon arrested. When Pat told a number of lies to the attorney in an alleged attempt to provide Tom with an alibi, the situation became even more suspicious. Tom had his own story — also a lie — and it didn’t match. He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. At the time of the murders, he and Pat had been married less than two months, and now Pat had the farm to herself. It wasn’t long before she tried to talk Tom into a suicide pact, which he later felt sure was an attempt to get him to die so she would inherit everything.

Pat was left alone, so she began working on Tom’s wealthy grandparents until they finally named her in their will as the primary beneficiary. Her house and barns burned down, and she forged Tom’s signature to get the insurance payments. Then she laced food with arsenic to feed to Tom’s grandparents. However, when they grew ill she was caught and ended up in prison for eight years.

Once she got out, she started up again with her scheming. She persuaded a wealthy couple from Atlanta, Mr. and Mrs. James Crist, to hire her as a nurse. It wasn’t long before they, too, got sick and the husband died.

In the meantime, Tom had served 15 and a half years and gotten out on parole. Investigators on the Crist case arranged to see him to find out what had happened the day he had shot his parents. It was their belief that Pat had not only choreographed the entire episode by fanning the flames of paranoia between father and son and then by sending them into a head-on confrontation, but also that she had fully expected Tom to die. The investigators believed Pat had hired someone to ambush Walter and Carolyn and to cut their phone lines, but they couldn’t prove anything. Tom’s story might solve the riddle.

As they spoke with him, a new piece of information came out: after shooting his parents in self-defense — afraid they meant to trap and kill him — he had run to find Pat and she had told him to find his own way home — 60 miles away. He had done so without question. Both of them had denied seeing each other that morning, and even as he protected Pat, it wasn’t long before he had wondered if he and his father had both been set up. Pat was a liar, Tom told the investigators. “Pat was a headstrong, manipulative type person that would do anything to get what she wanted — and you do not know she was doing it.” He had given her everything: his money, his power of attorney, his home, and his heart, and she had taken full advantage. The tragedy of his life would never have happened, he believed, if he hadn’t married Pat.

Once again, Pat was facing prison time. In a shrewd and controversial plea bargain, she agreed to seven charges, including theft, attempted murder, and posing as a registered nurse, with the proviso that she never be charged with the murder of Mr. Crist or investigated for the murder of Tom’s parents. One again, she was sentenced to eight years.

In an update on her Web site, Rule writes that Patricia Allanson has been free from prison since 1999 and lives with her stepfather and his new wife.

While it seems evident that Pat was among those women who set other people up to kill, some women do the killing and then deflect the blame to others.

Among American crime legends is that of Winnie Ruth Judd, otherwise known as “tiger woman,” “wolf woman,” the “blond butcher,” and the “velvet tigress.” Journalist Jana Bommersbach read the local news articles in Arizona library archives and then tracked down people familiar with the case, including Judd herself, to retell the story in The Trunk Murderess: Winnie Ruth Judd. From Bommersbach’s point of view, there was much to question about the investigation, sentencing, and subsequent punishment of a woman who insisted that the facts are different than the legend allows. Edward D. Radin, in Women Who Kill indicates that the Judd’s many conflicting statements during her trial point to her guilt.

October 16 in 1931 landed on a Friday. Winnie Ruth Judd, 26, was a medical secretary and the daughter of a minister. She was an attractive blue-eyed blonde in her mid-20s, living in Phoenix, Arizona, where the crime took place. That night, she had planned to be with her closest friend, Hedvig “Sammy” Samuelson; and Sammy’s housemate, Agnes Anne LeRoi. In fact, they were to spend the next three days together, but something happened around 11 p.m. that night. According to those who arrested and prosecuted her, Winnie Ruth waited until her friends were asleep and then shot them to death. Her motive was to eliminate them as competition for the married man she loved.

On October 19, the Southern Pacific train arrived in Los Angeles, coming in overnight from Phoenix. The baggage handler claimed that two trunks in one of his cars smelled pretty bad, and one was leaking brownish liquid. They were set aside for inspection. A blonde tried to collect them with a claim check, but when they insisted the trunks be opened before she could have them, she walked away and disappeared.

Eventually the police opened the trunks. Inside one was the nude body of a woman, crammed into a jack-knife position. The second trunk held the head and body parts of another woman. Both victims had been shot in the head, and the dismembered woman was also shot in the left breast and right hand. An abandoned suitcase found in a restroom contained the missing torso.

It wasn’t difficult to learn the identities of the victims, since snapshots and letters were also inside the trunks. They were Anne and Sammy, and Sammy was the one who had been cut up. The place where they had been killed was traced back to Phoenix, to the bungalow where they had lived. Inside the place, police found bloodstains and pieces missing from the carpet that matched the piece of bloody carpet found in the trunk. There was blood on the sidewalk and both mattresses were missing from the beds.

Those who had seen Winnie Ruth the morning after the murders saw nothing amiss, and she had been typing all morning. Later in the day, people noticed that her left hand was bandaged.

Neighbors reported shots in the bungalow late on Friday night. A friend of Anne and Sammy’s said that when she left the place at 10:00, Sammy was in bed and Anne was preparing for the same. Winnie Ruth had not been there.

The police found Winnie Ruth’s ailing husband in Los Angeles. Twenty-two years her senior, he was surprised to hear she had been in town, and he assured investigators that she and the victims were close friends. She had even written him a chatty letter the day after the time when the murders had taken place and he saw no indication in it that she was in trouble.

She called her husband on October 23rd, and he met her with an attorney. She told police that Sammy had shot her in the hand. When the bullet was removed, doctors saw that her body was bruised.

Then a torn-up letter was found in the drainpipe of a Los Angeles department store. It appeared to be a confession written by Winnie Ruth to her husband. She admitted that she’d told harmful lies in the past and that she and the two victims had quarreled over a man. Sammy shot her in the hand and she managed to shoot Sammy twice. Then he feared that Anne would blackmail her, she shot Anne, too. She packed them into the trunks over fear of being hung. She insisted she had killed the two other women in self-defense.

Winnie Ruth admitted to writing the letter, but then denied it. A handwriting expert for the prosecution later claimed it was her hand-writing, but the alleged time of death did not match that of the neighbors who heard the shots.

Then Winnie Ruth changed her statement. She had accused the victims of being “perverts,” but the prosecutors believed she was now trying to appear to be insane. Pathology reports indicated that both women had been shot while lying in bed and Sammy had been dismembered immediately. The facts contradicted Winnie Ruth’s statement. The police also suspected that she’d shot herself in the hand some time on Saturday afternoon so that she could claim self-defense.

During her trial in 1932, several medical experts said she was sane and quite crafty, but her defense team dug up a family history of insanity and a few incidents in Winnie Ruth’s past that made her mental state questionable. However, an all-male jury found her guilty of first-degree murder. She was to get the death penalty.

Winnie Ruth appealed this, but failed, so then she went into a grand jury and said that a man with whom she was in love had been involved, too. He was the one who had packed the bodies in the trunk. She stuck to her tale of self-defense. The jury indicted the man, who denied any involvement whatsoever, and asked the parole board to commute Judd’s sentence to life.

The board didn’t go for it, so her defense attorney asked for another sanity hearing, and during it, Winnie Ruth cried and screamed in such a way as to make people believe she was emotionally out of control. One doctor predicted that once the gallows was taken off the table, her malingering would be revealed.

Nevertheless, the jury fell for it. They decided that she was insane and she was placed in a psychiatric hospital. Almost at once, her insane behavior stopped. She fled from the hospital on numerous occasions, but was always brought back. Eventually she was released on parole.

The man she had named was never tried.

She spent almost 39 years in prison — at that time the longest sentences ever imposed to that point on a killer. While her motives for murder remain elusive, it’s likely that love was at stake. She was seen with a man on the Sunday morning after the murders, while the one she had named in the trial denied any relationship with her. The theory was that she’d set him up to deflect attention away from her true love, should anyone have seen them together.

Winnie Ruth exhibited none of the signs of psychosis, and her play-acting and ability to manipulate others indicates something more along the lines of a psychopathic female who wanted to eliminate hindrances to her own goals. She claimed years later that she was far too small and weak to have committed the crimes on her own, but she could have done so and then had assistance with the clean-up. Whatever the case may be, she certainly did shoot both women, all evidence indicates that she did it while they were in bed, and she was certainly part of the plan to ship their remains to another state.

Winnie Ruth displays the same cold calculation and disregard for others as those women who have come to be known as Black Widows.

Margie Velma Barfield’s first husband died while drunk and smoking in bed. Because he was abusive like her father, there were those who believed that this “Death Row Granny” did him in, but that wasn’t really her style. She preferred poison and she seemed to like to watch her victims die writhing in pain. Starting her killing career in her late 30s, she took out her second husband in 1971, followed by her mother. Both deaths were attributed to natural causes and both netted Barfield some money, which she desperately needed to feed her growing addiction to tranquilizers. In fact, it was this addiction that became her defense years later for committing four murders: she’d been in a fog and didn’t know what she was doing when she fed arsenic to her victims. The jury convicted her and in 1984 she died by lethal injection in North Carolina.

A Black Widow is a woman who kills family members — generally a string of spouses. She’s named after the deadly spider that mates with a male and then eats it, and according to Michael Kellerher in Murder Most Rare, she doesn’t begin her killing until after she’s 25. Her reasons are generally tied to personal gain (money, status) or to being rid of a burden, and she tends to kill for over a decade before she’s finally stopped. She’s not the classic serial killer who feels compelled by sexual or delusional motives, but she may certainly kill enough people in a similar manner to be called a serial killer. She tends not to kill strangers, but doesn’t restrict her murderous activity to family. She’s generally patient and fairly organized in her approach, and favors the use of poison.

Mary Ann Cotton killed her mother, all of her children, several stepchildren, an acquaintance, and four husbands with arsenic. They all died of “gastric fever,” a diagnosis common in the 19th century.

Belle Sorrenson Gunness, a Norwegian-American, insured her first husband and two of her children before killing them in the early 1900s and collecting the money. She took her other two children and bought a pig farm in Indiana, which she turned into a graveyard. Her then-husband, Peter Gunness was first. He was found under a large meat-grinder, his skull crushed. Belle soon put “lonely hearts” ads in the paper and those men who answered those ads disappeared.

When a fire leveled the place in 1908, investigators looked for Belle’s burned body and began to turn up one corpse after another that had been interred in the farm’s foundation or buried in the yard. The charred body of a headless woman was thought at first to be Belle, but the size and height were wrong. Then her two remaining children were found buried there as well. All of the victims had been poisoned. A handyman seen running from the fire was charged with arson, but he insisted that Belle was still alive. It was she who had burned down the house, faked her death, and then left. He’d even driven her to the railroad station. He also said that she’d had 49 victims — far more than the official estimates of a dozen or so. People speculated that some of her victims had been fed to the pigs. Belle was sighted many times, but always managed to get away. Then in 1931 in Los Angeles, an elderly woman named Ester Carlson was charged for killing her husband. Before her trial commenced, she died, and someone who had known Belle recognized her from a photo in the newspaper. The police found a trunk in a room where the deceased woman had been staying and it contained photos of Belle’s children. Belle Gunness had managed to get away yet again.

three children

The “giggling grandma,” Nannie Doss, dispatched four husbands during the 1940s and 50s, but she claimed that she’d done it for love, not money. She wanted the perfect mate and the men she had married failed to measure up. It was easy enough to slip each of them rat poison and move on to the next prospect — but also collect the insurance money. She also killed her mother, two sisters, two children, a grandson and a nephew by poisoning. Michael Newton points out that she had been molested by several men, hinting at a possible motive, but in a memoir that she penned from prison for Life magazine, she said she had killed because she enjoyed it.

Among the most prolific Black Widows was Vera Renczi in Hungary during the early part of the century. After she’d get involved with a man, she would suddenly grow jealous and afraid of rejection, so she would kill her lovers one by one. She then preserved the remains. When she later confessed and led investigators into her basement, they found her son (who had tried to blackmail her), her two husbands, and her many lovers in 35 separate zinc coffins.

Many Black Widows include their children among their victims, but women who kill only their children are another breed altogether.

While Susan Smith long held the title for the most famous murdering mother, she lost it to Andrea Pia Yates in 2001.

On October 25, 1994, Smith drove to John D. Long Lake outside Union, South Carolina, to contemplate a letter written to her by her married lover: he did not want to see her any longer. She claims she attributed this to the fact that she had two children by another man, her former husband, which her lover did not want around. To Smith’s mind, there was only one thing to do.

She parked on the gravel boat ramp and thought about what to do while Michael, three, and Alex, age 14 months, were asleep in the back. She had to kill them both, she believed, and then herself — or so she claimed. Smith put the car into neutral and felt it move toward the water. She got out, hesitated, and then reached into the car to release the emergency brake. The Mazda, lights still on, rolled forward into the water. Alex and Michael were securely strapped in. It would all be over in moments.

Smith watched as the car floated and filled with water. Finally it went under and she ran to a nearby house, screaming that a black man had accosted her at a traffic light and taken her car with her sons inside. It wasn’t long before investigators figured out what she had done, found the car, and brought the two small bodies out of the water. Smith was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Andrea Yates, 36, lived in Houston, Texas, and had five children. On June 20, 2001, she killed them all. She waited for her husband, Russell, to leave for work and then one by one, she drowned three of her sons, ages two, three, and five, in the bathtub. She then placed them on a bed still wet and covered them with a sheet. Next was six-month-old Mary, the youngest. While Yates was involved in this horrendous deed, her eldest son Noah, seven, happened to wander in to see what was going on. “What’s wrong with Mary?” he asked. Then he ran from the bathroom but Yates chased him down, dragged him back to the tub, and drowned him right next to Mary. She left him there floating in a tub full of feces, urine and vomit, where police whom she herself had called found him.

Yates also had called her husband and told him, “It’s time. I did it.”

He asked what happened and she said, “It’s the kids.”

“Which one?” he asked.

“All of them.”

From all appearances, he wasn’t surprised. He’d known that his wife was having problems — she’d always had them after the birth of one of their children — and her postpartum depression from Mary’s birth had worsened in the past weeks since her father had died.

The primary question in this case was whether or not Yates had killed the children while in a state of psychosis or had knowingly done it to escape a life she hated. Timothy Roche delved deep into her history for Time and discovered a rather disturbing picture of a troubled family, including a long history of mental illness for Yates.

Andrea and Russell had married in 1993, and after the birth of their first child a year later, she began to have violent visions: she saw someone being stabbed. However, she and her husband had idealistic, Bible-inspired notions about family and motherhood, so she kept her tormenting secrets to herself. She didn’t realize how much mental illness there was in her own family, from depression to bipolar disorder.

As Andrea had one child after another, she took on the task of home-schooling them, which friends say she was good at doing. Yet in her fragile mental condition, the pressure eventually took its toll.

Once a high school valedictorian and high achiever in college, Andrea sank into a lonely existence until she approached Russell for a relationship. Her goal in life was to please others and avoid disapproval. She worked as a nurse, and once married, aspired to have as many children as God would allow.

After two children, Russell decided to “travel light,” and made his small family live first in a recreational vehicle and then in a bus once used for a religious traveling crusade. Andrea didn’t complain, but she had another child, making their 350 square foot living quarters rather cramped. She sank into a depression. In 1999, she tried to kill herself with a drug overdose, and Russell and Andrea’s mother finally got her into treatment. Later she said she had just wanted to “sleep forever.”

She was discharged “for insurance reasons” and then she got worse. She told psychiatrists that she was hearing voices and seeing visions about getting a knife. Then Russell found her in the bathroom one day pressing a knife to her throat. He took it away and got her hospitalized. She confessed to one doctor that she was afraid she might hurt someone. On the antipsychotic drug, Haldol, she improved slightly, and relatives pressured Russell to buy a house for his family. He did so.

Still, Andrea was secretive and seemingly obsessed with reading the Bible. Russell thought that was a good thing, and despite doctors’ warnings to have no more children, they had a baby girl, Mary, late in 2000. Russell believed he’d spot the onset of depression and get help if needed.

When Andrea’s father died a few months later, she stopped functioning. She wouldn’t feed the baby, she became malnourished herself, and she drifted into a private world. Russell forced her into treatment under psychiatrist Mohammed Saeed. He received scanty medical records from her previous treatment and put Andrea on Haldol, then discontinued it. He had not heard from Russell — who claimed not to know — about her hallucinations, and he observed no psychosis himself, so he felt Haldol was unnecessary. After ten days, he discharged Andrea into her husband’s care.

Russell’s mother came to help, but Andrea wound up back in the hospital for depression. When she started to eat and shower, she was sent home, with the proviso that she continue outpatient therapy.

Russell was worried, but Saeed assured him that Andrea did not need shock treatment or Haldol. He reportedly told Andrea to “think positive thoughts,” and to see a psychologist. However, he did warn Russell that she should not be left alone.

Andrea sat at home in a near-catatonic state, and to Russell, she seemed nervous. However, he did not think that she was a danger to the children, so he left her alone on the morning of June 20. His mother would be by in a few hours, so he felt sure everything would be okay.

How wrong he was. Once he’d left the house, Andrea began to fill the tub. She started with Paul, the three-year-old, holding him under water until he stopped struggling. Then came Luke, John and Mary, the youngest. The last one was Noah.

It was no sudden act; Andrea admitted later that she’d been considering it for several months. At times, she indicated that she’d done it because she was not a good mother, and at other times that the children were not developing normally and she had to save their souls while they were still young. Autopsies indicated from recent bruises that the boys had struggled, and the fist of one had frozen around a shank of Andrea’s hair.

She was charged with knowingly and intentionally causing the deaths of the children with a deadly weapon (water), and her case became a high profile arena for the battle of medical experts. At her hearing, her prison psychologist, Dr. Gerald Harris, claimed that she wanted to be executed so that she and Satan, who possessed her, would be destroyed. While she pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, her competency even to be tried came under question. She claimed that Satan was coming to her in prison and conversing with her and she insisted she would not enter a plea of not guilty. She did not need an attorney, and she wanted her hair cut into the shape of a crown. She believed the number of the Antichrist, 666, was imprinted on her scalp. Still, the judge felt she could assist in her own defense.

During the trial in early 2002 for the deaths of Noah, John and Mary, psychiatrist Phillip Resnick defended her, explaining that she suffered from schizophrenic delusions and believed that killing her children was the right thing to do, while psychiatrist Park Dietz aligned himself with the prosecution. He admitted that she was seriously ill, but insisted that she had known that what she was doing was wrong. He also pointed out that she did not act like a mother who believed she was saving her children from Satan, and she had kept her plan a secret from others. She even admitted that she knew what she had done was wrong, and by Texas law, these facts were sufficient for the jury to convict Yates of first-degree murder.

Texas once had allowed insanity to include the inability to conform one’s acts in accordance with the law, but then they’d dropped that part and decided that knowledge alone could serve as the criterion.

During the penalty phase, the same jury quickly returned a sentence of life in prison rather than death, and Andrea Yates received this news with little emotion.

Mothers are responsible for most child abuse in America that ends in death. The third National Incidence of Child Abuse and Neglect report numbers as high as 78%, and according to Dr. Joseph Deltito, a professor of psychiatry at the New York Medical College, mothers outnumber fathers in the deaths of biological children by seven to one. Often they claim to be victims of a range of disorders from postpartum depression to post traumatic stress to outright psychosis, and they’re supported by a wealth of mental health agencies and social groups. Some go so far as to say that society is responsible. Yates had voiced her depressive symptoms, according to Cheryl Mayer, who promotes understanding of such incidents. No one took notice of the potential for danger. It was up to the doctors involved to know about the many cases like this (up to 20% of all women suffer postpartum depression) and to take steps to supervise the condition. When they didn’t, it was the doctors who were culpable, not Yates.

“Women sometimes experience serious hormonal shifts which can lead to radical mood swings,” said Dr. Tina Tessina to Time. “There is often a very serious disconnect between what women feel after they’ve given birth (depressed, tired, in pain) and what women are told they’re supposed to feel as new mothers (elated, joyful, selfless).” According to her, Yates’ depression could have been building for a long time without being obvious (although clearly it was obvious), while Dallas psychologist Ann Dunnewold indicated that such depressions can at times evolve into hallucinatory psychosis.

Yet while mothers who suffer from a stress disorder may win the sympathy of some, not all mothers can fall back on this excuse. One mother who lost all ten of her children eventually shocked the nation with her belated confession.

Some people believed she was the unluckiest mother alive. Life magazine even did a story on her in 1963 as the most famous bereaved mother in the country. Marie Noe had one child after another, ten in all, and every single one of them died. One was stillborn, one died right after birth, but the others had all seemed healthy. Only one lived as long as 14 months. For each there was an investigation, and for eight of them the conclusion was the same: sudden infant death syndrome, also known as SIDS.

Then on June 28, 1999, Noe shocked those involved with the cases when she pleaded guilty in Philadelphia to killing her children. The second shock came when it was learned what the sentence would be: 20 years probation. She was 70. She wasn’t going to have any more children, that was true, but how did 20 years amount to punishment for the deaths of all those children? Andrea Yates got life in prison for five and Susan Smith for two.

Perhaps it was because the confession itself was in some doubt.

The murder spree seems to have begun in 1949, when her first child was born, and to have ended in 1968. All were dead within months after birth, yet the autopsies were inconclusive. There was no evidence of violence or foul play, but an adult can smother a child without leaving a mark.

Stephen Fried, a reporter for Philadelphia Magazine, got interested in the case when he spotted some clips about Noe in a book called The Death of Innocents. That author claimed that any multiple cases of SIDS from the same family should be investigated as potential murder. Fried interviewed the Noes, the medical examiner, and other parties, and then after writing his story, he gave his findings to authorities on March 24, 1998. “We just weren’t meant to have children,” Noe had stated to him, while her husband had added, “The Lord needed angels.” There was just too much oddity to this tale to accept past conclusions, so medical examiners reviewed the autopsy reports and thought it likely that the children had been smothered. In retrospect, health care workers recalled Noe has being “emotionally flat” with regard to all her losses and as rarely visiting the children when they were hospitalized. She had assumed that each child would die quickly, and a nun remembered that Noe had once threatened a baby during feeding with, “You better take this or I’ll kill you.”

The police brought Marie Noe in for questioning, and she eventually confessed to smothering four of her children. The other four she wasn’t clear about. She didn’t remember how they died, although investigative reports at the time quote her as saying that just before they died the children turned blue and were gasping. One of them had been caught in plastic from her husband’s dry-cleaned suit. (He had not been home at the time of any of the deaths.) Insurance policies had been taken out on six of the children. After the ninth death, the Noes had tried to adopt — and to insure that child — but Marie got pregnant again and the adoption process was dropped.

On August 5, 1998, she was arrested for eight counts of murder.

Philadelphia district attorney Lynne Abraham commented on why it had taken so long: “What really is telling is that our refusal or our unwillingness to believe moms kill children may have played a role in this.” Even the defense attorney yielded to the system and made a statement to the effect that it was important for Mrs. Noe to understand what she had done “before she passes on to the next world.”

However, some people questioned the confession, since Noe was intellectually slow and perhaps felt coerced by strong-arm tactics. A group of geneticists even offered to test her blood, since they believed it was possible that if she had a certain rare metabolic condition inherited through the mother, she might have passed it down to each of her children. It’s called mitochondrial DNA disease. The mitochondria are present in most human cells and they convert food to energy. When many are diseased, the conversion process builds up lactic acid in the blood and brain, which can make the person die quite suddenly. When the condition is not fatal, it can still affect the mental processes and create Alzheimer-like symptoms. Sometimes mitochondrial disease is confused with schizophrenia. Observers of Noe’s behavior thought she might be suffering from it and passing it on, while groups like the Portia Campaign believed the children’s deaths could be attributed to any number of problems, including peanut allergy.

While Noe did admit to smothering four of her babies, her confusion and the pressure of an interrogation could have contributed to what amounts to a false confession. She might have admitted to anything. In the end, she pleaded guilty to eight counts of second-degree murder.

Plenty still needs to be done for research on female killers to catch up to what has been done on male killers, but it seems clear enough that despite less intense aggression, women can be just as dangerous as men. They account for a small percentage of the total number of murders committed by men, but when they set their minds to kill, they have to ability to carry it out and to repeat that act numerous times without remorse.

No one thought there was something wrong with 39-year-old Deanna Laney on Mother’s Day weekend in 2003. That’s why they could not have predicted what she was about to do.

A housewife in New Chapel Hill, Texas who saw herself as a religious sister to Andrea Yates, the housewife who drowned her five children in 2001, Laney began to see “signs.” Her 14-month-old son, Aaron, was playing with a spear. That was the first signal from God that she was to do something to her children.

She resisted, not certain that she understood. But the signs continued.

The case was broadcast on Court TV, and covered by newspapers, television talk shows nationwide and by Internet Web sites.

When Aaron presented Laney with a rock that day, she later reported that she believed she was supposed to pay attention. This was a symbol. Later that same day, he squeezed a frog. Then she understood. She was to kill her children, either by stoning them, strangling them or stabbing them. God had shown her three ways.

Again she told God no, but again she felt pressured to comply. “Each time it was getting worse and worse,” she later said, “the way it had to be done.” In other words, the more she resisted, the worse the death would be for her children. She decided that rocks would be preferable to strangulation, so she found some in preparation.

Laney knew she had to “step out in faith.” She had to trust God, and she believed that God would use her brutal deed to do something great. He had done such things in the Bible. Then when Laney woke up before midnight on May 9, she knew that the time was at hand. She had already hidden a rock in Aaron’s room, so she went there first.

Lifting the rock, she hit Aaron hard on the skull. He began to cry, alerting her husband, Keith. He asked what was wrong and Laney kept her back to him to prevent him from seeing what she was doing. She assured Keith that everything was okay. But it wasn’t okay. Aaron was still breathing, so she put a pillow over his face until she heard him gurgle. She silently told God that He would have to finish the job.

Next Laney went after her other two sons. She took Luke, six, outside first in his underwear and smashed his skull by hitting him repeatedly with a large rock. Then she dragged him by the feet into the shadows so that Joshua, eight, would not see him. She left the stone, the size of a dinner plate, lying on top of him.

Joshua was next and Laney repeated to him what she had done with Luke, placing them together in a dark area of the yard.

Afterward, she called 911 to report, “I killed my boys.”

When the police came, they found Aaron still alive. He was taken away and it eventually became clear that both his vision and motor skills were severely impaired.

Outside, the police saw Laney standing still in blood-stained clothes. She indicated where she had left the boys and they found the bodies lying beneath large rocks. Both boys had serious head wounds. Laney was arrested, leaving her bewildered, horrified husband to wonder what had happened.

Laney’s case had many parallels with that of Andrea Yates. Both women lived in Texas and home-schooled their children. Both were deeply religious. Both felt they had no choice but to do what they did to their children. Both called 911. And both had some of the same psychiatrists assessing their states of mind for their trials. Five experts came into the case for Laney, including Dr. Philip Resnick, who had served on Andrea Yates’ defense team, and Dr. Park Dietz, who was hired by the prosecutor.

But Laney’s 2004 trial unfolded quite differently.

While the defense psychiatrists had no trouble testifying that Laney had been delusional and psychotic at the time of the crime and could not appreciate that what she was doing was wrong, the surprise came with the prosecution’s expert, Dr. Park Dietz. He had been instrumental in convincing a jury that despite her terrible history of mental illness Andrea Yates had known that what she was doing was wrong and thus she was sane when she murdered her children. In the Laney case, he surprised everyone by saying the opposite.

From his assessment, he decided that Laney did not know that what she was doing was wrong. She believed she was following God’s orders. She admitted that she might have been aware that what she had done was illegal, but she was not thinking about that. She imagined that she and Andrea Yates, who also had started with the youngest, would together be the two witnesses when the world came to an end.

“She struggled over whether to obey God or to selfishly keep her children,” Dietz testified. His impression was that she had felt she had no choice.

Another psychiatrist for the prosecution, Dr. Edward Gripon, agreed that the presence of mental illness was obvious. Several of the experts thought that Laney had suffered from an undiagnosed psychosis over the past three years.

One more expert witness was Dr. William Reed, a court-appointed psychiatrist who used the word “crazy” to refer to Laney, and he agreed with the others.

Among the evidence they used was Laney’s post-crime demeanor. Six days after the attacks, she was calm as she described for psychiatrists what she had done. There were no tears. She was awaiting her children’s resurrections. With a smile, she said that because she had obeyed God, “I feel like he will reveal his power and they will be raised up. They will become alive again.” Dr. Resnick said that since she did not believe she had carried out God’s orders perfectly — she wasn’t certain about Aaron — she lapped up water from the floor and from a toilet bowl.

After getting antipsychotic medication, she eventually saw her acts in a different light and showed remorse. She realized with horror that she had suffered from a hallucination that had triggered her acts.

Laney’s sister, Pam Sepmoree, testified that Laney had been acting strangely in the days leading up to the murders. She was losing weight, eating less, and reading her Bible more. Sepmoree said that the boys were her sister’s life.

Despite this unprecedented agreement among all the psychiatrists, prosecutors nevertheless presented a case against Laney that certain behaviors indicated sanity. She had said that she believed that her husband would think her acts were wrong, so she tried to keep Aaron’s cries from alerting him. She had called 911 to turn herself in. And she had told a jailer that she might need an attorney. In addition, Laney had no documented history of mental illness, only self-reported episodes: delusions about her baby’s feces and a hallucination of smelling sulpher, which she associated with the devil.

Jurors got the case on the afternoon of April 3, and it took them seven hours that same day to acquit Laney of all charges by reason of insanity. She was transferred to a maximum security hospital where medical evaluations will determine when she can eventually be released.

On May 23, 2004, Jose Marquez, 38, was found dead in his South Side Chicago home. He had been shot to death in the back of the head. A week later, Kenneth Redick, 37, was similarly discovered murdered in his home. Then more than two weeks passed, according to Chief Tactical, before a third man, Kevin Armstrong, 24, was killed in a parking lot. Apparently he had been gunned down after leaving a currency exchange. Money was always taken from the victims, from $30 to $200. No link was found among the victims, and there were no clear leads. Whether the Chicago police had a serial killer was not yet clear, but two detectives went to work on it. June would pass into July before they fully connected the dots.

A fourth victim, 30-year-old Ayesha Epps, was found in a South Side alley, shot in the back of the head. She had been a friend of Caroline Peoples, 26, who was also linked to one of the other victims, a man she used to date. And she was linked to another woman, Angela Ford Wright (the Chicago Sun Times reports her name as Wright-Ford), also 26, who also knew two of the victims. She had been romantically involved with Redick, and was a health care aide for Marquez. Neither woman apparently knew Armstrong — or at least their association with him has not been clarified. He appears to have been at the wrong place at the wrong time.

The women’s arrest was announced on July 3, the day after Epps was found. Detective William Filipiak, who with Detective Eileen Heffernan cracked the case, told news sources that both had made videotaped confessions to the crimes. They were charged with four counts of first-degree murder and four counts of armed robbery. Like Aileen Wuornos, a Florida-based serial killer from 1990, they allegedly had used the promise of sex to lure the men, but they had intended instead to rob and kill them.

The fourth victim, Epps, was apparently shot during an argument.

No weapon has been recovered and neither woman has a prior criminal record.

These crimes echo the work of two females who carried out more than 100 violent robberies in Chicago during the 1890s, according to The Chronicle of Crime by Martin Fido. The police referred to them as “the Kitty and Jennie Gang,” and they managed to keep their spree going for at least seven years.

Crime

Kitty Adams worked as a white prostitute in a black brothel and was known as the “Terror of State Street,” for her ability to use a razor. Jennie Clark was younger, and together they apparently devised a game in which Jennie would lure men into an alley for sex. Instead, those johns found a knife at their throats, wielded by Kitty, who demanded that they turn over their money if they wanted to live.

One man identified them and turned them in to the police, but the case was dismissed by a judge who decided that men who were foolish enough to put themselves in that position in that area of town had gotten what they deserved. According to Fido, the two women returned to their game.

While there was no evidence that they killed any of these men, the MO is similar: lure men with what will make them vulnerable and then take advantage.

Even as people watched Scott Peterson be convicted for the murder of his pregnant wife and their unborn son, the news came from Missouri on December 16, 2004, that another pregnant woman had been killed. This story, however, was much more macabre. Bobbi Jo Stinnett, 23, was eight months pregnant with a baby girl. She had met a woman, Lisa Montgomery, on an Internet message board and possibly at a dog show, and had apparently arranged to meet. Little did she know that Montgomery had targeted her because she was pregnant.

Montgomery allegedly met Stinnett in her Skidmore home, where she strangled her to death and removed the baby from her womb. She then took the baby from Missouri to Kansas, where she hoped to pass the child off as her own. In the meantime, Stinnett was found lying in a pool of blood in her home. She had been speaking with her mother on the phone and had told her that a woman whom she’d met on the Internet had just arrived. Later that day, Stinnett’s mother discovered her, barely alive, and called the police. Paramedics arrived, but failed to save her. The medical examiner indicated that she had been cut open laterally to facilitate removal of the baby. The umbilical cord had been cut, and Stinnett was clutching strands of blond hair in one hand.

A delayed Amber Alert was called to expand the search across state lines, while detectives versed in computer forensics examined Stinnett’s e-mail. They soon determined the identity of her likely attacker, who was using a fake name, Darlene Fischer (screen name Fischer4kids), and who was ostensibly seeking to purchase a dog from Stinnett, who was knowledgeable about rat terriers.

A tip phoned in by someone who saw a Honda resembling the one the authorities were seeking helped to establish that the killer had fled to Kansas. On the following day, authorities located the child in good health in Melvern, Kansas, and arrested Montgomery. DNA tests confirmed that the child was the Stinnetts’. Zeb Stinnett, the baby’s father, was allowed to take her home. He named her Victoria Jo.

Montgomery, 36, had deceived her husband, who was not charged. The mother of two high-school-age children, Montgomery had supposedly lost the child she was carrying (or so she told people). On the day of the murder, she had called her husband from Topeka to say that she had given birth while on a shopping trip there. He drove to meet her, little suspecting that the child not only did not belong to him, but had been allegedly removed from a murdered woman. Montgomery actually showed the infant around to people at a bank, alerting one woman to notify the police because the infant was obviously premature. Montgomery ‘s former husband, who was in the process of seeking custody of their two children, told reporters for the Associated Press that Montgomery had often sought attention by pretending to be pregnant, but she’d had her tubes tied 14 years earlier.

She was charged with kidnapping resulting in a death and held in prison. Hers was the eighth such incident recorded by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children since 1983. Such crimes are generally committed by women using a confidence scam. They usually have a history of deception (Montgomery did), and they tend to develop a relationship with a “predetermined target.” In 2002, a study was published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences on kidnap by Cesarean section. The study found that those who committed such crimes were self-centered, obsessed with babies, and tended to live in a fantasy world, but were not considered psychotic. They often fail to think ahead to the questions they’ll be asked or about practical matters such as birth certificates.

The New York Daily News posted a list of similar cases in which women so strongly craved babies that they were motivated to murder:

In Oklahoma in 2003, Effie Goodson shot Carolyn Simpson, who was six months pregnant, but the baby died as well, and Goodson was arrested.

Michelle Bica was a neighbor of Theresa Andrews in Ohio, who was close to giving birth. Bica informed her husband that she was pregnant in 2000 and then shot Anderson, taking the baby to claim as her own. The police closed in, so she committed suicide rather than face the music.

That same year, Kathaleena Draper was suffocated by her aunt, Erin Kuhn, after she decided not to give her aunt the baby she was carrying. Kuhn cut the child from Draper’s womb with a knife, but the infant died.

Carethia Curry and Felicia Scott were friends in Alabama. Curry was pregnant and Scott decided that she wanted the child, so she killed Curry to get it. The baby survived, but Scott was arrested.

In Chicago, a couple named Fedell Caffey and Jacqueline Williams desperately wanted a baby, so they found a woman, Deborah Evans, who was ready to give birth. They killed her, along with two of her children, and escaped with her baby. The police caught up to them and arrested them. Both went to death row.

In 1987, Darci Pierce abducted Cindy Ray near a prenatal clinical in New Mexico and attacked her. Pierce strangled the pregnant woman, killing her, and used a car key to remove the unborn child. The child survived the attack.

On September 25, 2006, newspapers across the country reported that the latest fetal snatching incident, perpetrated in Illinois, was much worse than first believed. Twenty-four-year-old Tiffany Hall, the suspect, talked about what she had done in a desperate attempt to acquire a baby for herself.

According to the News Democrat, Hall indicated that she had drowned the three children of her one-time close friend, Jimella Tunstall, 23. The oldest, age seven, was found in the dryer and the others, ages one and two, in the washing machine at their East St. Louis apartment. But the appliances had not been turned on and there was little water in the washing machine, so it was clear that they’d been killed elsewhere, probably drowned in a bathtub, and then placed in the machines. It was five days before Hall finally led the police to them, but before she took their lives she’d committed another murder.

A few days earlier, on September 15, Hall had killed Tunstall, seven months pregnant, keeping the body in her mother’s basement for several days before dumping it in a weed-strewn lot nearby. The mutilated corpse was found on September 21. The autopsy indicated that she’d been bludgeoned with a blunt object and while she was unconscious, her unborn female child was cut out of her womb with a sharp implement. A pair of scissors was found near the body, and St. Clair County Coroner Rick Stone indicated that the cause of death was bleeding from an abdominal wound.

However, the fetus had died on September 15 as well, probably during the attack, so Hall took it to a regional hospital and told the staff that she’d been raped, causing a miscarriage. Yet she left before she could be checked, and the staff who spoke with her thought she was too calm to have been through such an ordeal. The sex crimes detective, Carolyn Wiener, thought the same thing and found many holes in her story.

It was Hall’s boyfriend who turned her in after she confessed the deed to him. He’d initially believed the baby was his, and they’d buried her together under the name, Taylor Horn, but then Hall admitted that she’d miscarried his child and had stolen this premature infant from her “cousin.”

Jeff Doan interviewed mental health experts on the subject for the Associated Press. Dr. Phillip Resnick, who assisted in the defense of both Andrea Yates (who drowned her five children) and Deanna Laney (who stoned hers), said that he interpreted the act of fetal snatching as the maternal instinct gone wrong. Its clinical name is “newborn kidnapping by Caesarean section.” The perpetrators are typically women who’ve learned they cannot have children or who have lost a child. Their longing to be mothers builds into a crafty determination to get a baby, so they look for a vulnerable pregnant woman. Mentally, they’ve gone so far beyond normal that the cost of a life to acquire a child seems minimal to them. The baby, they think, will complete them, and they’re often jealous of women who do have babies or are about to give birth. Resnick says that being barren takes on terrible symbolism, so stark on the minds of these offenders that they can see only their own need, and not the ultimate consequences to themselves or others.

However, even with all the calculation that often occurs in these cases on the way to acquisition, there have been no others in which the perpetrator actually committed mass murder in the process. Hall killed five individuals.

On September 25, Hall pled not guilty to the deaths of Tunstall and the fetus, and charges in the other three murders are still pending. Given the nature of the crime and the possibility that it involves a psychotic delusion, it’s likely that if she goes to trial, her defense will be some form of insanity or diminished capacity. In fact, her attorney, public defender Randall Kelley, indicated he’d have her tested for mental competency. It’s not clear, despite her claim to her boyfriend, that Hall was ever even pregnant. However, her two daughters had been removed from her custody for three years in 1999, due to abuse, but were returned to her four years ago. Psychiatric testing will probably probe the effect on her of this circumstance.

Alt, Betty and Sandra Wells. Wicked Women. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 2000.

Davis, Carol Anne. Women Who Kill: Profiles of Female Serial Killers. London: Allison and Busby, 2001.

Coverage of the Andrea Yates Trial, CourtTV, Feb-March, 2002.

Fried, Stephen. “Cradle to Grave,” Philly Mag Online. Pillymag.com. 1998.

Graham, Anne E. and Carol Emmas, The Last Victim. London: Headline, 1999.

Hickey, Eric. Serial Murderers and Their Victims. 2nd Ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1997.

Jones, Ann. Women Who Kill. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1996.

Jones, Richard Glyn, ed. The Mammoth Book of Women Who Kill. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2002.

Kelleher, Michael D. and C.L. Kelleher. Murder Most Rare. New York: Dell, 1998.

Klein, Victor. New Orleans Ghosts, New Orleans: Lyncanthrope Press, 1993.

Lane, Brian and Wilfred Gregg. The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. New York: Berkley, 1995.

Manners, Terry. Deadlier Than the Male: Stories of Female Serial Killers. London: Pan Books, 1995.

Newton, Michael. The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. New York: Checkmark Books, 2002.

Norman, Ken. “It’s only Natural,” portia.org.

Roche, Timothy. “The Yates Odyssey,” Time.com, January 20, 2002.

Rule, Ann. Everything She Ever Wanted. New York: Pocket, 1992.

Schecter, Harold. The A to Z Guide to Serial Killers. New York: Pocket, 1996.

Schurman-Kaufman, Deborah. The New Predator: Women Who Kill. New York: Algora, 2000.

Scott, Gini Graham. Homicide: One Hundred Years of Murder in America. Los Angeles, CA: Lowell House, 1998.

Smith, Katherine. Journey into Darkness. New Orleans: DiSimonin Publications, 1998.

Williams, Stephen. Invisible Darkness. New York: Bantam, 1996.