|

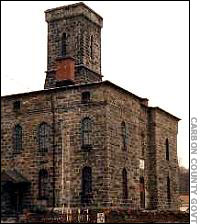

| Carbon County prison |

Cell 17 was a cramped and dismal hole at the far end of the old Carbon County prison in what was then Mauch Chunk, a damp and hellish place where even stray rays of sunlight were wrestled to the ground and shackled as they oozed through the rusting iron latticework of the old cell door. Even now, nearly 130 years later, it still reeks of wet stone and misery, the kind of place where only a roach or a rat could find comfort, and then only fleetingly.

A roach, a rat, or maybe an Irish miner.

Alex Campbell had been a miner.

|

| Alexander Campbell, portrait |

A handsome man with piercing eyes, and a broad back, though stooped slightly from the years he had spent in the pits, he had commanded the respect of his fellow miners. To some, that made him a hero. But to those who ran the mines and the railroads, who all but owned the miners, keeping them in a kind of peonage, those same attributes made Campbell and dozens of other men just like him dangerous.

To them, Campbell, John "Black Jack" Kehoe, Michael Doyle, John "Yellow Jack" Donahue, Edward Kelly, and others, many others, were more than simply dangerous, they were murderers, wild-eyed terrorists, and foreign agitators. These were men who participated in a secret society and who, in the minds of the privileged class and their underlings, wanted nothing less than the total destruction of the social order. They were men who had made powerful enemies, among them the mine bosses, the thugs they hired and dressed in the uniform of the Coal and Iron Police to control the workers, the media that parroted whatever the privileged class said, even the Catholic Church, the one organization that was supposed to above all comfort the afflicted Irish Catholic miners.

To the men of prestige and power, Campbell and his cohorts were nothing more than vermin to be exterminated, likes rats and roaches. They were the Molly Maguires.

From the courtyard outside the prison, Campbell and Donahue, Doyle and Kelly, had for days been able to hear the carpenters working on the gallows, specially constructed to snap the necks of four men at once, and designed, it is said, in accordance with certain obscure biblical passages drawn from the apocrypha.

|

| A Molly Maguire Story |

The four had been convicted of Molly Maguirism and murder, their convictions based almost exclusively on the testimony of a single Pinkerton detective, a man who decades later would be widely discredited, and secured by a prosecutor specially appointed for the task, who also happened to be the president of one of the largest railroad and coal companies in the nation at that time.

And now they were going to hang.

|

| Carbon County Jail |

It was the morning of June 21, 1877, and every square inch of space in the old jail courtyard was crammed with people who had come to see Campbell and his fellows consigned to hell, according to reports published at the time and repeated often since.

By all accounts, the four men carried themselves with dignity. There was no panic, no pleading, no calls for mercy. Perhaps they knew that there was no use asking the same authorities who had concocted the case against them to show mercy now.

But, as the legend goes, when the guards, accompanied by a priest, entered Cell 17 that morning to take Alexander Campbell to his death, the charismatic miner stooped over and dabbed the palm of his hand with a substance from the floor.

Turning to the guards, he is said to have stated, according to several published reports, "I am innocent, and let this be my testimony."

With that, Alexander Campbell slammed his open hand against the wall of his cell, leaving behind a mark that remains there to this day, despite every effort for 130 years to scrub it away.