Into The Dark: The My Lai Massacre — Introduction — Crime Library

There will never be another year in America like 1968. Why that year became one of the most tumultuous periods in our history will probably never be known. It began on an ominous note when one of Americas most fervent enemies, North Korea, seized a U.S. Navy intelligence ship, named the U. S. S. Pueblo, in the Sea of Japan on January 23. They held the ship and its crew for many months and nearly started a full-scale war. In Vietnam, the massive Tet Offensive, launched by the Viet Cong against almost every major city in the south, caused massive casualties on all sides.

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King touched off numerous riots in dozens of American cities. Two months later, the brother of a murdered President, Senator Robert Kennedy, was assassinated in Los Angeles at the hands of an Arab fanatic. Colleges across the country were enveloped in a wave of protest and violence over the Vietnam War, which was killing hundreds of young Americans every week.

In August, the Democratic Presidential Convention in Chicago was wrecked by thousands of young people who fought the Chicago police on live TV, symbolizing the anguish of a divided nation. Richard Nixon was elected President in November and man made his first tenuous step into eternity as Apollo 10 astronauts said Christmas prayers from the dark side of the Moon. It seemed as if anything could happen that year.

And then, there was My Lai.

D.C. (AP)

D.C. (AP)

Quang Ngai province is a stunning, exotic mixture of mountains, jungle, rice paddies and beaches along a vastly unblemished shoreline. To the west, toward the Laotian border, beyond more mountains and hills than can be imagined, as far as the eye can see, the ancient lands of Vietnam stretch into the horizon. Jungles so thick and treacherous, an American soldier couldn’t move a half-mile a day. The heat was like a vise it could sap the will of the strongest man and put a brave soldier on his knees. Rusted shells of French military vehicles, armored carriers and tanks lay hidden in the bush, overgrown with two decades of weeds and vegetation, dim reminders of the Indochina War during the 1950s and the ultimate defeat of European colonialism.

The village of Chu Lai was in the province of Quang Ngai, a highly contested area whose control shifted almost daily between the Viet Cong and South Vietnamese forces during the 1960s. It is located on QL-1, the one and only national highway of South Vietnam, which hugs the coast along the South China Sea. It was, and still is, a highway that is mostly unpaved and littered with potholes. A traveler was just as likely to come across a water buffalo as speeding motorcycles, a column of military vehicles, ARVN soldiers (South Vietnamese), farmers, civilians, school children, U.S. soldiers, Korean ROCs and even the VC who also used QL-1 to get around Vietnam.

The 11th Brigade built a base camp in the town of Duc Pho, a small village in the southern part of Quang Ngai province. This was an area that was dominated by the Viet Cong for many years prior to 1967. Sympathy for Ho Chi Minh and his “holy cause” ran deep. So much so that the only way to defeat the Viet Cong in the Duc Pho-Mo Duc district was to wipe out the villages. By the time the 11th Infantry Brigade arrived in the town of Duc Pho, it was estimated that 70% of the homes in the province were already destroyed. And this was months before the massive Tet Offensive of February, 1968 when North Vietnam launched a nationwide coordinated attack on hundreds of towns and villages in South Vietnam. Total destruction was the military’s solution on how to deal with an enemy that could not be understood and often could not be seen. Villages across Vietnam were bombed, burned, bulldozed and buried.

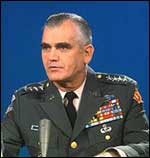

Westmoreland, 1967

(CORBIS)

General William Westmoreland, Commander of American Forces in Vietnam, once wrote: “So sympathetic were some of the people to the VC that the only way to establish control…among the people was to remove the people and destroy the village.” The civilian population, caught between the Viet Cong who ruled the night and the Americans who took over during the day, suffered at the hands of both. In the rural areas, where electricity was mostly unknown and families lived on the same plot of land for centuries, political loyalties were often subject to the whim of whoever was holding a rifle. Water buffalo was the main source of power and farmers knew little else except the methods, tradition and culture of growing rice. To many young American soldiers, Vietnam was a land of primitive technology and so alien to their own experiences, so different than what they were accustomed to seeing, it was like going back in time to a pre-historic era.

1968 (Courtesy Mark Gado)

In Quang Ngai Province during 1967 and 1968, the Viet Cong remained in control in almost all of the rural areas. Despite continuous bombardment by American artillery and thousands of strategic bombing missions by U.S. Navy jets, enemy forces were still strong and ruled the countryside. In November, 1967, U.S. forces and North Vietnamese Regulars (NVA) engaged in a fearsome battle to the death in the hills of Dak To on Thanksgiving Day. The terrifying story of that battle on Hill 875 was still fresh in the minds of American soldiers and spoke volumes of the amazing persistence of the Viet Cong (Page and Pimlott, p. 289). A few miles to the east of QL-1, the hamlets of Son My and My Lai were the scene of continued fighting where the area was frequently covered with mines and booby traps. These deadly traps took a heavy toll, both physically and psychologically, on the American soldier.

In February and March of 1968, Charlie Company, of the 1st Battalion, 11th Brigade, suffered severe losses as a result of these traps. In one instance, while patrolling near Son My, the company stumbled upon a heavily laid minefield. As the explosions went off among them, the men tried to push forward. It was the worst thing they could have done. More explosions ripped through the helpless soldiers. Broken and severed limbs were everywhere. When it was over, 15 men were killed and wounded. By the time early March rolled around, Charlie Company had suffered 28 casualties and had yet to actually see any Viet Cong. They were seething with an anger and hatred for an enemy that, to them, was mostly invisible.

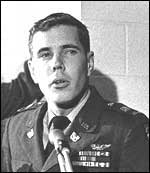

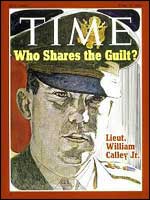

Calley Jr, 1969

(AP)

By all accounts ever published about Lt. William “Rusty” Calley, 24, he was an ordinary kind of guy. Raised in Florida, the son of a Navy veteran, he came from a stable background. He attended Palm Beach Junior College in 1963 but he did not receive a degree by the time he entered the Army. His grades were undistinguished and he flunked out “with grades in seven courses of two Cs, one D and four Fs.” His desire for education, like a lot of other things in his young life, faded away and by 1964, he had stopped attending college altogether. Calley had no special talents, no record of deviant behavior and was considered a typical American. He was short in stature, just 5’3,” neither good nor bad looking. A newspaper once referred to Calley as “the nice boy charged with murder.” .

(CORBIS)

Calley had many jobs before he entered the service. He worked for an insurance company as an investigator, a train conductor and washed cars at a car wash. He eventually drifted to San Francisco in 1966 where he lived for several months until he received notice from the Selective Service System. The letter said that his draft status was being reevaluated and he should report for a medical examination. Calley started the long drive back home in July, 1966. By the time he reached New Mexico, his car broke down. Calley had no money, no job and no way of getting back home to Miami. With the prospect of a limited and uncertain future staring him in the face, he stumbled into an Albuquerque recruitment center on July 26, 1966 and enlisted in the Army.

Division

After he completed Basic Training at Fort Benning, Georgia, Calley was transferred to Fort Lewis, Washington to receive training as a clerk. Not thrilled with the prospect of becoming an Army clerk, Calley applied for Officer Candidates School (O.C.S.), a six-month training program that could promote a lowly ranked E-2 into the rank of a 2nd Lieutenant, an officer who could command a platoon of 30 men, or at certain times, a company consisting of 200.

Upon graduation from O.C.S. in 1967, Calley was dispatched to Schofield Barracks, Hawaii where he trained with the men of Charlie Company of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry. In early December 1967, the company, as a whole, was sent to Vietnam. “Charlie was really made for war! We were mean, we were ugly,” Calley said of the men in his command. In Vietnam, they became part of the famed 23rd Infantry Division, also called the Americal Division, whose headquarters were in the sprawling base camp at Chu Lai on the windy shores of the South China Sea.

But soon, the consensus among members of Calley’s platoon in Vietnam was almost unanimous: they did not respect him. One of his riflemen had this to say about Calley’s abilities: “I wonder how he got through Officer’s Candidate School. He couldn’t read no darn map and a compass would confuse his ass.” To some, he had the hostile insecurity of someone who felt that he was too short in stature. An infantryman in the 1st platoon said: “Calley is just gung-ho and has no common sense…because he is small he must have been pushed around all his life by bigger people. Once he got in the Army he found he had a lot of authority.” Later, another soldier told the Army Criminal Investigation Division (C.I.D.) that Calley was so distrusted by members of his own unit that they offered a reward to whomever would shoot him. No one had any respect for him as a platoon leader. His own commanding officer, Captain “Mad Dog” Medina, a career Army officer, frequently ridiculed Calley in front of his own men. “The captain called him Lieutenant Shithead regularly,” said another G.I. .

On the night of March 15, 1968, the men and commanders of Charlie Company gathered outside Captain Medina’s “hooch”. That very day, the company had a memorial service for Sgt. George Cox, a popular N.C.O. who was killed by a booby trap while on patrol near QL-1 the day before. The men were demoralized, angry and frustrated with an enemy that so far, had gotten the best of them.

Captain Medina briefed the company on the next day’s assault on My Lai. What was said at this meeting and exactly what the orders were concerning the mission has remained in dispute. Some of those at the meeting say that Medina gave direct orders to kill all the civilians. “He (Medina) stated that My Lai #4 was a suspected VC stronghold and that he had orders to kill everybody that was in the village,” testified Spec. 4 Max Hutson of the 2nd Platoon . Others disagreed. Pfc. Gregory Olsen remembered the briefing differently and testified to the Army C.I.D.: “Captain Medina would never have given an order to kill women and children.” Whatever was said, and it is impossible to determine exactly what orders were issued, the men of Charlie Company saw the next day’s mission as an opportunity to pay back the Viet Cong for their booby traps, their mine fields and the blood of the 11th Brigade.

Assault Group

The early morning of March 16, 1968 in Southern Quang Ngai was calm and cool. For one brief moment at 5:30 a.m., the incessant chatter of the birds and monkeys was at rest. A light breeze rolled in from the China Sea and rustled through the swaying palms outside LZ Dottie.

The men of Charlie Company began to assemble. As the Huey transport copters from the 174th Helicopter Assault Company began to crank up their turbines, a vivid and luminous moon could still be seen in the twilight sky. The stars pulsated brilliantly above and to the drifting mind of a young soldier, it was easy to imagine a vacation in some distant tropical land, for despite the chaos that ripped the country apart, Vietnam could have that magic. All in all, a beautiful dawn it was.

At approximately 7:20 a.m., Lt. Calley walked over to the Huey chopper called a “slick” and with his right hand, pulled himself into the rear compartment where a door gunner was busy strapping himself in. The men of the 1st Platoon made their final check on ammunition and supplies. They quickly boarded the waiting aircraft, filled with the expectation that the company may be “getting even” with an enemy that was mostly unseen, mysterious and hated.

banner (AP)

Also on board one of these nine choppers, frantically securing his own camera equipment, was Army photographer Ron Haeberle, assigned to record the event for Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper. Less than 15 miles away to the southwest, the people of My Lai 4 slept, unafraid, unsuspecting; their dreams were filled with visions of a peaceful future, unaware of the sword of vengeance that was about to fall upon them, a nightmare for which nothing could have prepared them. The choppers gently lifted off the tarmac and banked south into a neat, tight “V” formation.

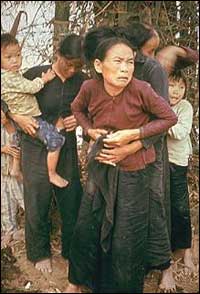

March, 1968 (Courtesy Mark Gado)

Other gunships from Chu Lai met up with the 174th a short distance from the western edge of My Lai. At approximately 7:45 a.m., artillery preparation of the landing zone began. On the ground, the residents of My Lai became aware of the pending attack. They were accustomed to running from the assaults of both the VC and the Americans. Villagers constructed bunkers and tunnels deep into the ground for many years, back to the time of the French when they ran from another enemy. Fleeing from the rice paddies, where they were already hard at work for hours, the inhabitants herded their children to safety until the attack was over. Even though no enemy personnel had been observed from the air, “Shark” gunships from the 174th descended on the scene and laid down a terrifying barrage of rockets and M-60 machine gun fire.

(TIMEPIX)

“There were so many people killed that day it is hard for me to recall exactly how some of the people died,” U.S. Army Pvt. Harry Stanley said to C.I.D. investigators (as reported by Seymour M. Hersh).

(TIMPIX)

When Capt. Medina’s chopper hit the ground, he reported over the radio that the LZ was “cold,” no incoming enemy fire. But that assessment quickly changed when Medina subsequently reported that elements of the attacking force were receiving enemy fire. Some of the attacking gunships reported suspected VC on the ground and fired upon the enemy as they raced for cover.

Meanwhile, the 1st Platoon, commanded by Lt. Calley moved from the southeast into My Lai. “The first killing was an old man in a field outside the village who said some kind of greeting in Vietnamese and waved his arms at us…This was the first murder,” Herbert L. Carter, a tunnel rat for Calley’s 1st Platoon, later testified. As the platoon sought out secure positions, some of the local villagers began to emerge. They knew full well that if they ran, the Americans would consider them Viet Cong. Unknown to them, for this day, everyone was considered VC.

Soldiers from the 1st Platoon opened up on the Vietnamese farmers; at least 5-9 were immediately killed. Soon, the platoon broke down into small groups or squads and moved throughout the village, shooting into suspected enemy positions at random. All around the men gunfire continued to erupt as the advancing soldiers began to fire at anything that moved. Cows, pigs, chickens, water buffalo, birds and gravestones were blown apart by machine gun fire and M-79 grenade launchers.

Some villagers were accidentally hit by gunfire and went to the soldiers for help. The men of the 1st Platoon cut them down. “She came out of the hut with her baby and Widmer shot her with an M16 and she fell. When she fell, she dropped the baby and then Widmer opened up on the baby with his M16 and killed the baby too,” said Carter in additional testimony to the Army C.I.D.

Another soldier, Pfc. Varnado Simpson, shot a woman, a baby. Afterwards, he went into a kind of shock. “The baby’s face was half gone, my mind just went…and I just started killing. Old men, women, children, water buffaloes, everything…I just killed…That day in My Lai, I was personally responsible for killing about 25 people,” said Simpson.

The platoon advanced further into My Lai without receiving any enemy fire at all. As they did, some of the men began to shoot inside the straw huts of the hamlet into what they considered “suspected enemy positions.” As the villagers attempted to flee, they were pushed back into the huts and the soldiers tossed in grenades. The frenzy of killing picked up speed and each violent event began to build on the last. An old Vietnamese farmer was captured by the 1st Platoon and, for no apparent reason, was bayoneted in the chest and thrown into a well. Another farmer suffered the same fate and after the second man was thrown into the well, a grenade was tossed in afterwards. This incident was witnessed by several of Calley’s men who later reported it to the C.I.D.

they were murdered

(TIMEPIX)

“In at least three instances inside the village, Vietnamese of all ages were rounded up in groups of 5-10 and were shot down…Women and children, many of whom were small babies, were killed sitting or hiding in their homes,” later wrote Lt. General William Peers, who performed the Army’s investigation into My Lai in 1970. Numerous rapes were committed against the young girls of the village, sometimes while their families were forced to watch. Everywhere, dead bodies of women and children littered the roads and fields of the burning hamlet. Captain Brian Livingston, a helicopter pilot and commander, wrote in a letter back home on that very day: “I’ve never seen so many people dead in one spot. Ninety-five percent were women and kids.”

(TIMEPIX)

Around 9:00 a.m., while the killing was at full throttle, members of the 1st and 2nd platoon rounded up some Vietnamese civilians. The soldiers brought them to the center of the village. This group consisted mostly of women, children, babies and old men who were too terrified to run away. They were eventually herded together in the middle of My Lai where they sat on the ground. Two soldiers from the 1st Platoon, Pfc. Dennis Conti and Pfc. Paul Meadlo, guarded the Vietnamese until Lt. Calley came along.

The civilians were then assembled into a large ditch. Unknown to them, Calley had just been reprimanded by Capt. Medina over the radio for his slow progress through the village. Calley saw the huge group of civilians, which at that time numbered about sixty.

“Take care of them!” Calley ordered the two soldiers and walked away.

Several minutes later, Calley returned and saw the civilians still alive. “I thought I told you to take care of them?” Meadlo responded by saying, “We are. We’re watching over them.”

“No, I want them killed!” Calley said. Then, as the terrified villagers cowered in fear deep inside the ditch, Calley lowered his M16 from approximately ten feet away and began to fire his weapon. Meadlo was ordered to do the same.

Later, he explained his actions to the Peers Commission in this way: “It’s not your right to refuse that order, and you go out there and do it because you’re ordered to.” For several minutes Calley fired into the panic-stricken crowd as babies and old people were torn to shreds. Meadlo finally broke into a crying fit and could not continue. But Calley pressed on. One by one he killed each survivor who tried to stand including mothers who attempted to shield their children. Months later, the Army’s investigative report summed up this event in very simple terms: “The villagers were herded into a ditch with the larger group of 60-70…At approximately 0900-0915 hours, Vietnamese personnel who had been herded into the ditch were shot down by members of the 1st Platoon.”

(AP)

While the killings and the rapes continued unabated on the ground, Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson, 25, piloted an H-23 bubble helicopter a few hundred feet above the burning hamlet. As he orbited the area, Thompson and his two-man crew saw a wounded female in a rice paddy. As he maneuvered the chopper closer, Thompson saw an Army captain kick the woman and shoot her in the head. A few minutes later, the crew saw dozens of bodies in a ditch near a dirt road. The chopper set down several times to investigate. The crew saw American soldiers taking a smoke break and it was apparent there was no ongoing firefight with the Viet Cong.

The chopper took off again. A few hundreds yards away, the crew saw U.S. soldiers firing into another ditch filled with Vietnamese. Thompson became enraged. He couldn’t believe what he was seeing. As he swept over the village, he saw about a dozen civilians splashing through the rice paddies. They were running for their lives from Charlie Company. Thompson landed his chopper between the civilians and the Americans. Calley showed up a minute later and had heated words with Thompson who was consumed with rage. He ordered his crew to turn their machine guns on the Americans and if the soldiers intervened, to fire on the young lieutenant. Thompson herded the terrified Vietnamese onto other gunships that offered assistance and flew them to safety to Quang Ngai City.

As W. O. Thompson’s choppers took off with the rescued civilians, Calley and his men moved to the eastern end of the village. On the way, he encountered other villagers being held by members of the 1st Platoon. They were near the edge of a small bridge that crossed an irrigation ditch. There were approximately forty to fifty Vietnamese women and children, including an elderly Buddhist monk.

Upon questioning, the monk managed to convey that there were no weapons or VC in the village. It was not the answer Calley wanted to hear. Just at that moment, a small child crawled away from its mother out of the ditch. According to later testimony, Calley tossed the baby back into the hole and shot the child. He then pushed the monk into the ditch and shot him without provocation.

Within moments, the firing started. Machine guns poured a lethal wave of death into the pit as pieces of bone and flesh flew into the air. Some of the soldiers, like Pfc. Robert Maples, refused the order to fire. He later told investigators: “I do now remember that Meadlo was one of those firing and he was crying at the same time. I know that he or the others did not want to kill those persons. This is not true of Calley because he seemed to want to kill.”

A short time later, the 3rd Platoon was sent into My Lai to clean up any “resistance” that remained. They immediately began to slaughter every human and animal they could find. One soldier jumped on the back of a water buffalo and stabbed the helpless animal with his bayonet. Any Vietnamese who survived the initial sweep by the 1st and 2nd platoons and emerged out from their hiding places were shot down immediately.

They “swept through the south side of My Lai 4 shooting anyone who tried to escape, bayoneting others, raping women, shooting livestock” and more. The entire village of My Lai was littered with corpses and dead animals. From the air, it looked like a huge killing field. Someone in a helicopter overhead shouted into the radio: “It looks like a bloodbath down there! What the hell is going on?”

But as far as anyone could tell, Charlie Company had not received even one round of enemy fire. The entire hamlet of My Lai 4, known as Tu Cung to the Vietnamese, had been wiped out. Families that had lived on this same ground for generations were eradicated. The village, except for the noise of the soldiers setting fire to the huts or farm animals thrashing about in the final throes of death, was quiet. Or as Pfc. Maples later told U.S. Army C.I.D. investigators: “I did not see anyone alive when we left the village.”

(TIMEPIX)

The cover up for what happened at My Lai began on the day of the killings. Calley’s soldiers who did not participate in the slaughter and the vast majority of Charlie Company who did not kill any civilians were so frightened and shocked by what they saw, they literally lost all sense of reason. It is important to remember that no single person who was present that day at My Lai knew the totality of what happened, not even Calley.

For the better part of the morning, the squads were separate from each other and out of sight of one another. Some killings took place inside the huts or in the bush where no one could see. Some soldiers saw only a few killings; others saw many. But no one saw all the killing.

The dimensions of the slaughter were so enormous, that the exact number of dead will never be known. The Peers Report later estimated the loss of life in the hundreds: “…it is evident that by the time C Company was prepared to depart the area, its members had killed no less than 175-200 Vietnamese men, women and children.”

The Criminal Investigation Division of the U.S. Army estimated 374 dead, not including personnel from Binh Tay, a nearby hamlet where additional killings took place. But the Vietnamese themselves, through an official report made to the Province chief and later forwarded to Division Headquarters at Chu Lai, charged that U.S. troops “assembled the people, and shot and killed more than 400 people at Tu Cung hamlet and 90 more in Co Luy hamlet.” The official memorial in the village of My Lai lists 504 killed, “182 women, of whom 17 were pregnant, and 173 children, of whom 56 were of infant age. Sixty of the men were over 60 years old…”

By the afternoon of March 16, while the operation was still in progress, 11th Brigade headquarters at Duc Pho knew that something drastic had happened at My Lai 4. In the following days, officers of the Americal Division met several times at Chu Lai to discuss the operation. Although inquiries were made about the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, no disciplinary action was taken.

The internal investigations were mostly of a superficial nature and surmised that the dead at My Lai were accidental due to artillery fire preceding the ground attack. The Peers Report concluded in 1970 that the inquiries at Divisional level “appear to have been little more than a pretense of an investigation and had as their goal the suppression of the true facts concerning the events of 16 March.”

In 1968, a soldier who completed his tour of duty in Vietnam wrote a letter to General Creighton Abrams, the commander of American Forces, about the mistreatment of the Vietnamese people by G.I.s. He received this reply from the assistant Chief of Staff of the Americal Division and future Secretary of State, then Major Colin L. Powell: “…relations between American soldiers and the Vietnamese people are excellent.”

The cover up continued for months and into 1969. Lies were told, false reports were filed and omissions were made by U.S. Army personnel. Some people claimed that there was no proof of an atrocity committed by the U.S. military. But one man knew better.

Only one person had the proof of what happened on March 16, 1968. Only one man had the irrefutable evidence of the killing and incredible brutality at My Lai. That man was Ron Haeberle, the Army photographer who witnessed the bloodbath, and his shocking photographs of the carnage would shame a nation and break the heart of America in a way it had never experienced before.

Ron Ridenhour, 21, arrived in Vietnam in January of 1968 and was assigned to the aviation branch of the 11th Infantry Brigade at Chu Lai. During that year, he became friends with the “grunts” (infantry foot soldiers) and often drank with the men on their off time in the clubs on the base. Ridenhour also was a member of a special unit called Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols (LRPS). Although he did not participate in the attack on My Lai, Ridenhour heard stories about what happened on March 16, including vivid descriptions of the killing. Over the next few months, the stories he heard originated from so many different sources, Ridenhour realized there must be some truth to them. When he returned to the United States after his tour of duty, he sat down in his home in Phoenix, Arizona and composed a letter that described his fears:

“It was late in April, 1968 that I first heard of ‘Pinkville’ and what allegedly happened there. I received the first report with some skepticism, but in the following months I was to hear similar stories from such a wide variety of people that it became impossible for me to disbelieve that something dark and bloody did indeed occur sometime in March, 1968 in a village called ‘Pinkville’ in the Republic of Viet Nam.”

He went on to explain where he was stationed while he was in Vietnam and to whom he spoke about My Lai and when. Ridenhour knew many details about the massacre through these conversations. He wrote:

“2nd Lieutenant Kalley (this spelling may be incorrect) had rounded up several groups of villagers (each group consisting of a minimum of 20 persons of both sexes and all ages.) According to the story, Kalley then machine-gunned each group…the population of the village had been 300-400 people and that very few, if any, escaped.”

Ridenhour also heard there was more than just one slaughter by “Kalley.” He wrote: “Kalley didn’t bother to order anyone to take the machine gun when the other two groups of villagers were formed. He simply manned it himself and shot down all villagers in both groups.”

Finally, Ridenhour explained why he wanted the truth to come out about My Lai. He said he believed in the principle of justice and felt that to let My Lai go unpunished would violate a fundamental concept upon which America was built. Tortured by the thought of mass murder committed by U.S. troops, and determined to get at the truth wherever it may lead, Ridenhour mailed his letter to dozens of government officials and to Congressman Morris Udall of Arizona. Later when Ridenhour was interviewed in Phoenix by the U.S. Army regarding his allegations, Colonel William Wilson described him as “an extremely impressive young man, and while his allegations were still only hearsay, he was depressingly convincing.”

(AP)

The letter provoked an immediate reaction within the government. Within weeks, several military agencies were alerted and many politicians became aware of the atrocity charges against the U.S. Army. By May, Ridenhour received a letter of acknowledgement from General William Westmoreland himself, who promised an investigation into the matter. Momentum was gathering like the pressure building inside of a volcano. Soon, it would erupt. And like a volcano, it would cause devastation everywhere.

Over the summer of 1969, the Army conducted an investigation into the actions of the 1st Battalion at My Lai. Headed by a no-nonsense Army officer, Colonel William Wilson, the inquiry involved the first face-to-face interviews with the soldiers who were actually there on March 16, 1968. Colonel Wilson was a North Carolina native, a highly decorated Green Beret and combat veteran of World War II. He received a Purple Heart for war wounds and served in many combat zones throughout the years including the Congo in 1965. Among Army personnel, he was highly respected and regarded as a “soldier’s soldier”. He conducted his interviews in full uniform wearing a chest full of medals so that the young soldiers would feel that he was one of them, an infantryman who knew the devastating pressures of close up war.

He began by flying to Phoenix to interview Ridenhour. Together they went over the details of his letter: names of people involved, what each one did, who said what to whom. From Phoenix, Wilson went on a criss-cross journey across America locating former servicemen who were in My Lai that day and others who spoke of the incident while in Chu Lai or Duc Pho. The more he learned about the massacre, the more worried he became. “I had prayed to God that this thing was fiction, and I knew now that it was fact,” Wilson wrote.

In June, 1969, Warrant Officer Thompson, the courageous pilot who threatened to turn guns on his own troops if they shot another civilian at My Lai, was brought to Washington, D.C. He was interviewed by Col. Wilson and supplied the details of his confrontation with a young lieutenant on the killing fields of My Lai. On June 13, he picked out Lt. William Calley from a line up. Thompson told Col. Wilson he estimated that there were between seventy-five and a hundred dead bodies in a nearby ditch, apparently shot by Calley and his troops.

1969 (CORBIS)

After ten weeks of inquiry, Colonel Wilson completed his report and submitted it to Lt. Gen. William Peers, who was conducting another more extensive investigation that would become a minute-by-minute account of the entire operation on My Lai on March 16, 1968. Every minuscule detail of the event was examined and investigated. The commission also made a return trip to Vietnam where graves were dug up and evidence collected. No stone was left unturned in the Peers Report which eventually grew to several volumes that contained hundreds of interviews, photographs, recordings and testimony of virtually anyone who had anything to do with My Lai. The Peers Report was devastating.

Its conclusions supported and surpassed every fear anyone had about the massacre. “Its (1st Platoon) members were involved in widespread killing of Vietnamese inhabitants (compromised almost exclusively of old men, women and children)…members of the 2nd Platoon killed at least 60-70 Vietnamese men, women and children as they swept through the northern half of My Lai 4,” wrote Gen. Peers. The report went on to detail many rapes, the shooting of old men and the killing and mutilation of babies. The Peers Report estimated the number of dead in the two locations where Calley fired his M-16 as between eighty and two hundred.

(AP)

In August of 1969, President Richard Nixon, on vacation in San Clemente, was told that Lt. William Calley and others would soon be charged with mass murder for the hundreds of killings at My Lai. Politically, it was a catastrophe for the Nixon White House. America was bitterly divided over the Vietnam War, Nixon was trying to drum up support for his policies and stifle the dissent at home. He also felt that the North Vietnamese would never fully negotiate if they knew that the American people were divided over the fate of the war. My Lai confirmed the worst fears of critics: that the war was senseless, brutal and fought against a backward people who were victimized by both sides.

Some of Nixon’s advisors urged him to press forward with full disclosure and a concentrated effort to prosecute all those involved in the killings. The deeper implications of My Lai and what it meant to America on a spiritual level were enormous. Advisor to the President, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, wrote a memo to Nixon in which he said:

“It is clear that something hideous happened at My Lai…I fear and dread what this will do to our society unless we try to understand it…For it is America that is being judged. And America will be condemned, unless we undertake some larger effort than can be had from a court martial.”

Calley, Jr

(TIMEPIX)

Many people believed the President should appoint a special investigator or a commission to show that the government was in control and the White House was showing true moral leadership. There were others who were deeply worried of what such a war crimes trial would mean. It would be America itself on stage; the whole Vietnam War issue would be explored, dissected, ripped apart in all its ugly truth. President Nixon decided to let the Army handle it with a court martial. On September 6, 1969, two days before he was to be released from the Army, Lt. William Calley was formally charged at Fort Benning, Georgia, with 109 murders.

For months, the appalling story of how a young Army Lieutenant and his platoon wiped out a village of civilians in Vietnam had been building across the nation. Rumors were heard by the press who later found that the Army was less than forthcoming about the event. News articles concerning My Lai were published in various newspapers but the story did not become mainstream for quite some time. On September 6, 1969, the Associated Press issued this brief, almost unnoticed news release:

“Fort Benning, GA (AP) An Army officer has been charged with murder in the deaths of an unspecified number of civilians in Viet Nam in 1968, post authorities have revealed. Col. Douglas Tucker, information officer, said the charge was brought Friday against 1st Lt. William L. Calley Jr., 26, of Miami, Fla., a two year veteran who was to have been discharged from the service Saturday.”

After Calley was charged, the story began to pick up speed. More details about the massacre began to appear. Seymour Hersh, a freelance reporter, spent weeks investigating the twisting turns of the My Lai tragedy. In November of 1969, the story finally broke in dozens of papers across the country. Hersh’s article, which appeared in the New York Times and later won a Pulitzer Prize, detailed the massacre as well as the Army’s efforts to cover up the truth.

On December 5, 1969, Life magazine ran Haeberle’s photos and erased any doubt of the stunning carnage that took place in My Lai. There, for the world to see, in bright unforgiving color, was the damning evidence of mass murder. The bodies of dozens of Vietnamese women and children lay frozen in time and history on the pages of Life. Dead babies lay next to their mothers; women with their clothes soaked in blood lay strewn upon some forgotten road; a little girl, seconds from death, stared into Haeberle’s lens, her face a mask of terror and confusion. There was no mistake: something horrible, something evil, something beyond anything America had ever seen before, had happened in My Lai. And worst of all, there was the sickening feeling that American soldiers, the heroes of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, conquerors of the Third Reich and saviors of the free world, were responsible for the slaughter.

(TIMEPIX)

Latimer (CORBIS)

The court martial of Lt. William Calley began at Fort Benning, Georgia on November 17, 1970. The prosecutor, Capt. Aubrey M. Daniel III, was a twenty-eight-year old attorney who had little trial experience. Calley was represented by George Latimer, a former military judge. According to the Army’s indictment, Calley was charged with the “murder of 109 Oriental human beings.” Even in spite of eyewitness testimony and the admissibility of Haerberle’s gruesome photographic evidence, prosecutor Daniel knew the case still would not be easy. Several members of Calley’s unit had agreed to testify but many did not. Some pled the 5th Amendment, mindful of the consequences of admitting to the horrors of My Lai under oath.

The jury consisted of six Army officers: one captain, four majors and a colonel. All had combat experience on the battlefields of Europe in World War II, through Korea and Vietnam. Among them, they held a Silver Star, 13 Bronze Stars, a Distinguished Flying Cross and a wide variety of other awards and commendations. Calley would be judged by his peers. They were men who knew the military, and more importantly, knew the hell of war through their own personal experiences.

During the trial, Calley was the model of the obedient soldier. Of course, he had a legitimate reason for doing so, since his defense would revolve around the concept of obeying orders. He lived on post at Fort Benning in his own apartment where he frequently entertained friends and supporters. He took the time to answer a great deal of fan mail from around the country while at the same time tried not to neglect his own future. Calley was very aware of the tremendous publicity that the case had received across the world. He signed a contract with Esquire magazine to publish his version of the events at My Lai and began working on a book about My Lai.

On January 11, 1971, former Pfc. Paul Meadlo, Calley’s partner at the killing ditch in My Lai testified. Meadlo, then 23, described in unemotional, straightforward terms, how he and Lt. Calley shot defenseless old men, women and children in a frenzied slaughter. “Calley backed off and starting shooting automatic into the people,” he said, “I was beside Calley. He told me to shoot. He burned off four or five magazines.”

Meadlo described the second group of killings a few minutes later. At the second ditch, a group of 80 to 100 women and children were gathered. “Then he started shoving them off and shooting them in a ravine. He ordered me to help kill the people too. I started shoving them off and shooting them,” he added. Meadlo admitted to many killings at My Lai, but legally, he was off the hook: the Government granted him immunity for his testimony.

Another former soldier, Dennis Conti, took the stand to describe his version of the events at My Lai. In response to questions by Capt. Daniel, Conti recounted the killings by the first ditch:

“So they Calley and Meadlo got on line and fired directly into the people…The people screamed and yelled and fell. I guess they tried to get up too” (Direct examination by Capt. Aubrey Daniels). “There was a lot of heads had been shot off, pieces of heads, flesh of the…fleshy parts of the body, side and arms, pretty well messed up,” he said. Testimony indicated that Calley had to reload his weapon between 10 and 15 times, while the victims scrambled around in the ditch.

(CORBIS)

When Calley took the stand, he defended the killings as part of his “job.” He said, “I did not sit down and think in terms of men, women and children…I carried out the orders I was given and I do not feel wrong in doing so.” Calley emphasized that as an officer, he was compelled to carry out his orders. “So it was our job to go through destroying everyone and everything in there…,” he said. For three days, Calley continued offering the Nuremberg defense of “only following orders.” After Calley’s repetitious testimony, Captain Ernest Medina took the stand and emphatically denied ever ordering anyone to kill women and children. “No, you do not kill women and children. You use common sense. If they have a weapon and they are trying to engage you, then you shoot back,” he said.

“Don’t you have a country? Don’t you live in this world? What the hell are you?” from All My Sons by Arthur Miller (1946).

On March 29, 1971, after the longest court martial in American history and thirteen days of deliberations, Lt. William Calley was found guilty of the murder of at least twenty-two Vietnamese civilians. Calley, then 27, stood erect as he heard the verdict. He saluted the jury foreman, Colonel Clifford Ford, and returned to his seat at the defense table. His attorney, George Latimer, told the press: “It was a horrendous decision for the United States, the United States Army and for my client. Take my word for it, the boy is crushed.”

The very next day, Lt. Calley stood in the same courtroom and read his statement to the jury prior to sentencing. He said that he was not at fault because he was only doing what he was trained to do:

“Nobody in the military system ever described them as anything other than Communism. They didn’t give it a race, they didn’t give it a sex, they didn’t give it an age. They never let me believe it was just a philosophy in a man’s mind. That was my enemy out there. And when it became between me and that enemy, I had to value the lives of my troops, and I feel that was the only crime I have committed.”

(AP)

Of course, Calley never mentioned the fact that not one round of enemy fire was ever received at My Lai that day and no Viet Cong were ever seen or captured. There was no contact with the enemy whatsoever and Calley nor any member of his platoon ever attempted to make that claim. His platoon suffered not a single casualty and there was no battle, as some people believed. The public’s reaction to My Lai was based on a misconception of fact that was never fully clarified. A few minutes after Calley read his statement, he received his sentence: life imprisonment at hard labor.

The sentencing, however, was not greeted with universal approval. Many Americans felt that Calley was simply a scapegoat and those in higher positions should also be held accountable. President Nixon wrote in his memoirs: “Public reaction to this announcement was emotional and sharply divided. More than 5,000 telegrams arrived at the White House, running 100 to 1 in favor of clemency.” Nixon, ever the politician, decided that mercy was in order for the young lieutenant. On April 1, 1971, just two days after the verdict, Nixon ordered Calley to be placed under house arrest while his appeal worked its way through the courts. “The whole tragic episode was used by the media and the antiwar forces to chip away at our efforts to build public support for our Vietnam objectives,” he wrote.

Across the nation, there were many demonstrations of support for Lt. Calley. The American Legion announced plans that it would try to raise $100,000 for his appeal. Draft board personnel in several cities resigned in groups. Several politicians spoke out in public criticizing the government’s prosecution of the soldiers at My Lai. “I’ve had veterans tell me that if they were in Vietnam now, they would lay down their arms and come home,” Congressman John Rarick told the New York Times.

But prosecutor Aubrey Daniel also did not remain silent. He wrote a highly publicized letter to President Nixon criticizing him for releasing Calley to house arrest: “How shocking it is if so many people across this nation have failed to see the moral issue…that it is unlawful for an American soldier to summarily execute unarmed and unresisting men, women and babies.”

apartment (TIMEPIX)

For the next few years, in Ft. Benning, Georgia, William Calley, the convicted mass murderer, sat in his home under house arrest, watching television reruns and cooking his own food. Whenever he went out to town for supplies, he had to be accompanied by two M.P.s. He waited out the years in his apartment, unbowed, convinced he had done something right in the service of his country. His self-serving statements during this time carried on the myth that he and the members of his platoon were engaged in some type of enemy action. “I’m sorry anybody had to die there, sorry I ever had to kill a soldier in Vietnam…but I’ll be very proud to have been in the U.S. Army and fought at My Lai,” he told Time magazine in 1971.

In 1973, his sentence was reduced to ten years by Secretary of the Army Howard Callaway. After a great deal of legal wrangling, Calley was paroled on September 9, 1974. He had served 3 ½ years under house arrest or approximately one month for every ten Vietnamese killed at My Lai. Today, William Calley lives in a self-imposed obscurity in Columbus, Georgia, working in a family-owned jewelry store. He refuses to give interviews or talk about Vietnam in public.

(TIMEPIX)

To many people at that time, the verdict against Calley was excessive and even unreasonable. There was a firestorm of controversy that seems somehow out of place when we view it from today’s perspective. But rarely has the My Lai incident been examined outside the realm of political considerations. Passions were high concerning Vietnam during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Anti-war advocates saw My Lai as a typical event by American soldiers and proof the war was immoral. Supporters of the war saw the massacre as something that happens in all wars and visualized Calley as a scapegoat for others higher up on the command ladder.

The court denied Calley’s claim of “obeying orders”, the defense of soldiers throughout history accused of similar crimes. Calley was convicted by combat veterans who appreciated full well the pressures and dangers of modern warfare. They knew that massacres of unarmed civilians by American troops were not a common occurrence and whenever it happened in the past, military courts prosecuted those involved.

Even if Calley had received orders to slaughter every old man, woman and baby in the village of My Lai, “any reasonable person would have realized that such orders were illegal and should have refused to carry them out.” In fact, many soldiers in Charlie Company did refuse a direct order to kill unarmed, defenseless civilians. Most soldiers knew that My Lai was not a battleground; there was no enemy contact and no incoming fire. In any case, Calley and his men were never ordered to rape and execute little girls.

(TIMEPIX)

Massacres in wars are part of the ugly truth about human conflict. They become possible when the ties that bind people together as fellow human beings are devalued or broken down. Those ties are so strong that a systematic procedure of dehumanization must take place before the killing can begin. That process includes a deprivation of the victim’s traditions, culture and existence that usually begins with labels such as “gooks”, “dinks”, “nips” and other derogatory terms that help define the victim as subhuman.

The mass murder of the Jews by Hitler’s Nazis began with a propaganda campaign during the 1930s designed to portray the Jewish people as something less than human and therefore deserving of extermination. It’s a lot easier to kill people when they are not thought of as people. One of the most disturbing aspects of My Lai was the men of Charlie Company itself. All the soldiers at My Lai were ordinary young men who represented a sort of cross section of America. They were not monsters. They were cooks, cab drivers, bus drivers, students, clerks. How could they do such a horrible thing?

(CORBIS)

In Vietnam, still a land of mystery and confusion to most Americans, near the hamlet of Son My, a monument stands in memory of those who perished on March 16, 1968. It will stand as a reminder of the awful crimes committed against a defenseless people who today, display surprisingly little bitterness. The monsoon season, which brings torrential rain in Vietnam every year, feeds the rice fields, nourishes the rivers and streams but has never washed away the searing memory of My Lai.

Very little ever changes in this timeless country. The Diem River, upon whose banks the dead once rested, twists its way out of Son My until it makes a turn to the west a few miles from the coast. Beyond the city of Tam Ky, gateway to the interior, it flows into the remote, vast wilderness of ancient valleys and forests where maps are useless and the graves of forgotten men are many; past the village of Son Ha and the hills of Dak To, where the blood of the VC and America’s young once flowed. The river winds its way deep into the bush, into the living jungle, until it disappears at last from view, descending into some distant, forbidden place whose caves and shadows conceal things that are better left undisturbed. It continues on, unseen, far into the unknown, into the dark, where few have ever gone and no one has ever returned.

monument (TIMEPIX)

“Into the Dark” is dedicated to those that didn’t make it back. Their honor and heroism in the name of our country will far outlast the story of My Lai.

Bigart, Homer. Ex-G.I. Says He and Calley Shot Civilians at My Lai Under Orders. New York Times}, January 12, 1971, p.1 and 12

Bigart, Homer. Calley Guilty of Murder of 22 Civilians at My Lai. New York Times, March 30, 1971

Bilton, Michael and Sim, Kevin (1993). Four Hours in My Lai. New York City, NY: Penguin Group

Duiker, William J. (1995). Sacred War. New York City, NY: McGraw Hill Publishers.

Hammer, Richard (1970). One Morning in the War: The Tragedy at Son My. New York City, NY: Coward-McCann Inc.

Hersh, Seymour M. (1970) My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and Its Aftermath. New York City, NY: Random House

Kamm, Henry (1996). Dragon Ascending. New York City, NY: Arcade Publishing

Kelman, Herbert and V. Lee Hamilton (1991) The My Lai Massacre Down to Earth Sociology. Henslin, James M., Editor. New York City, NY: The Free Press.

Nixon, Richard M. (1978) RN:The Memoirs of Richard Nixon. New York City, NY: Gossett and Dunlap Publishers.

Olson, James S. and Randy Roberts (1998) My Lai, A Brief History with Documents. Boston, MA: Bedford Books

Peers, Lieutenant General William R. U.S. Army. Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations in the My Lai Incident (known as the Peers Report).

Page, Tim and Pimlott, John (1988). Nam-The Vietnam Experience 1965-75. New York City, NY: Mallard Press

Range, Peter. Rusty Calley: Unlikely Villain. Time magazine, April 12, 1971.

Ridenhour, Ron. Letter written to government officials dated March 29, 1969

Wilson, William “I Had Prayed to God That This Was Fiction” American Heritage magazine, February, 1990 p. 45-53.