Nathan Leopold & Richard Loeb, Crime of the 20th century

On Wednesday, May 21, 1924, fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks walked home from school by himself. A car stopped and a familiar face appeared in its open window. Bobby got in the car raced away.

Around dinner time, Bobby had not come home nor had he contacted his parents, Jacob and Flora Franks. His brother Jack and his sister Josephine had no idea where he was. Perhaps he was playing tennis at the Loebs, Jack suggested. But when his father looked over at the Loeb’s tennis courts, Bobby was nowhere to be seen.

While Flora called Bobby’s classmates, Jacob contacted the headmaster of the school to find out if Bobby could have gotten himself locked in the school building. He called Samuel Ettelson, a prominent lawyer and friend, to determine what to do. Ettelson and Jacob searched the entire school building, but found no sign of Bobby.

While they were gone, Flora got a phone call. A man calling himself Johnson told her, “Your son has been kidnapped. He is all right. There will be further news in the morning.” Flora fainted and remained unconscious until her husband and Ettelson came home.

At two in the morning, Jacob and Ettelson went to the police, but since none of the police officials that Ettelson knew were on duty at that hour, they decided to come back later that morning.

The Franks were residents of Kenwood, a wealthy neighborhood in Chicago. They lived quietly among the Jewish elite of Kenwood, but had not been accepted socially for several reasons. They had renounced their Jewish faith to become Christian Scientists. Jacob had made much of his money running a pawnshop, which didn’t recommend them socially to the powerful Jewish executives, bankers and attorneys in the neighborhood.

The next morning, the mailman arrived with a special delivery letter:

“Dear Sir:

As you no doubt know by this time, your son has been kidnapped. Allow us to assure you that he is at present well and safe. You need fear no physical harm for him, provided you live up carefully to the following instructions and to such others as you will receive by future communications. Should you, however, disobey any of our instructions, even slightly, his death will be the penalty.

1. For obvious reasons make absolutely no attempt to communicate with either police authorities or any private agency. Should you already have communicated with the police, allow them to continue their investigations, but do not mention this letter.

2. Secure before noon today $10,000. This money must be composed entirely of old bills of the following denominations: $2000 in $20 bills, $8000 in $50 bills. The money must be old. Any attempt to include new or marked bills will render the entire venture futile.

3. The money should be placed in a large cigar box, or if this is impossible, in a heavy cardboard box, securely closed and wrapped in white paper. The wrapping paper should be sealed at all openings with sealing wax.

4. Have the money with you, prepared as directed above, and remain at home after one o’clock. See that the telephone is not in use.”

It was signed George Johnson and guaranteed that if the money were delivered according to his instructions that Bobby would be returned unharmed.

While Jacob went to get the money, Ettelson called his friend who was chief of detectives for the Chicago Police Department.

An enterprising newspaperman had been tipped off that there was a kidnapping involving the Franks’ boy. He had also heard that a boy had been found dead in a culvert near Wolf Lake, a probable drowning victim. He relayed the description of the dead boy to Mr. Franks, who did not think it matched his son. Franks’ brother-in-law went check it out.

When the telephone rang, “George Johnson” told Ettelson, “I am sending a Yellow Cab for you. Get in and go to the drugstore at 1465 East Sixty-third Street.” Ettelson handed the phone to Jacob and the message was repeated. In the trauma of the events, both men immediately forgot the address of the drugstore.

The phone rang again. This time it was Jacob’s brother-in-law. The boy that had been found dead in the culvert was Bobby Franks.

The investigation of Bobby Franks’ death went into high gear. Unfortunately an opportunity was lost when Jacob Franks and Samuel Ettelson forgot the address of the drugstore where they were to await instructions from the kidnapper. Soon a Yellow Cab arrived at the Franks’ home, sent by the kidnapper, but the driver had not been given any instructions as to the destination.

Shortly afterwards, at the Van de Bogert & Ross drugstore on East Sixty-third Street, a phone call came in for a Mr. Franks. The caller was told that there was no Mr. Franks there. A few minutes later, another call came for Mr. Franks, along with a description of Jacob Franks. The druggist told the caller that there was no man in the store of that description.

Several rewards were publicized: Jacob Franks offered $5,000; Police Chief Morgan Collins offered another $1,000; the two major Chicago newspapers, the Tribune and the Herald and Examiner, each offered $5,000.

State’s Attorney Robert E. Crowe took charge of the investigation. Crowe’s assistant, Bert Cronson, a nephew of Samuel Ettelson, was assigned full time, along with two others on Crowe’s staff.

Crowe, a forty-five-year-old politician known for his pugnacity and stubbornness, was trying to establish himself as the top Republican in the Chicago area. A favorable solution to the Franks’ case would go a long way to achieving that goal.

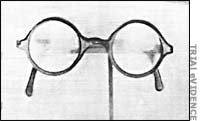

The culvert near Wolf Lake in which the body was found was near railroad tracks. In fact, it was members of a railroad crew that had lifted the naked body of the Franks boy from the water. Bobby’s clothes were not found nearby, but a pair of eyeglasses were lying on the ground.

The ransom note, police scientists determined, was typed by a novice typist on an Underwood typewriter. Coroner Oscar Wolff told the press that only an educated person could have drafted a letter in such perfect English. “That would signify intelligence, a dangerous attribute in a criminal….Greed would be the controlling passion, and, dead or alive, they intended to cash in on Robert Franks, the millionaire’s son.”

Given that the ransom note was written by someone well educated, the police focused upon three teachers at the Harvard School where Bobby Franks attended. They were taken to the police station and grilled for hours while their apartments were searched. One of the teachers was released, but the other two were kept in custody.

The small horn rimmed glasses found near the body did not belong to the boy. The frames, which were made of Xylonite, were chewed at the ends. The prescription was very common. The chances of finding the owner of the glasses seemed slim, but every attempt was made. The newspapers carried photos of the glasses and the police contacted optical companies in the area.

On Friday, May 23, Richard Loeb, a handsome nineteen-year-old University of Chicago student and neighbor of the Franks family, was at his Zeta Beta Tau fraternity house with Howard Mayer who was the campus liaison to the Evening American. Loeb suggested that they try to locate the drugstore that the kidnapper had instructed Jacob Franks to go to with the ransom money. Just as the two of them were about to check the various drugstores, two Daily News reporters, one of whom was a ZBT member, came into the fraternity house and decided to go with them.

Eventually, they found the Van de Bogert & Ross drugstore and confirmed that there had been two calls the previous day for Mr. Franks. “This is the place!” Loeb shrieked enthusiastically to the others. “This is what comes from reading detective stories.”

Mulroy, one of the reporters, asked Loeb if he knew the murdered boy. Loeb told him he had, then he smiled and said, “If I were going to murder anybody, I would murder just such a cocky little son of a bitch as Bobby Franks.”

On Friday the 23rd, the coroner’s inquest was held. Dr. Joseph Springer had conducted the autopsy. Bobby Franks had died of suffocation, perhaps when his kidnapper held his hand over the boy’s mouth or when he had shoved something down the boy’s throat. There were a number of wounds on the boy’s body, which suggested that he had fought with his captor.

There were small wounds on the right and left sides of his head, plus bleeding and bruises from a blunt instrument on Bobby’s forehead. Some chemical had been poured on his face and his penis. While there was some dilation of the rectum, Springer said that Bobby had not been sexually abused.

When police talked to the game warden for the area around Wolf Lake, they found that one frequent visitor to the area was Nathan Leopold, a nineteen-year-old ornithologist. Police had a servant awaken the young man so that he could come down to the police station for questioning. Young Nathan Leopold was questioned, but the answers he gave about his birdwatching expeditions were very credible and he did not arouse suspicion.

The Leopolds were a very highly respected family of German Jews who had arrived in the United States in the mid-1800’s. The family had made its fortune transporting grain, minerals and other freight on the Great Lakes. They lived in the same wealthy Kenwood area as the Franks family.

A cabdriver came forward with the story of two well-dressed young men who had hired him to drive them to the home of Jacob Franks. Once there, the two men sat in the cab for several minutes, but did not get out. He then drove them to another destination.

Eight days after the murder, police discovered that the hinges on the pair of eyeglasses were very unique and had only been sold on three pairs of glasses in the Chicago area. One of those three pairs of glasses belonged to Nathan Leopold.

State’s Attorney Crowe was sensitive to questioning the son of a prominent family in the police station with voracious reporters swarming around. Instead, on May, 29, 1924, Nathan Leopold was to be taken to a room at the LaSalle Hotel where he could be questioned discreetly.

Police arrived at his house in the afternoon just before one of Leopold’s classes on birds. They asked him if he had lost his glasses and he said that he hadn’t. Later, they searched the house, but the glasses could not be found.

Eventually, Leopold confirmed that the eyeglasses were his and that he must have lost them a few days before the death of Bobby Franks when he had gone birding at Wolf Lake on Saturday and Sunday, May 17 and 18 with two other boys. He said that he had tripped and the glasses probably had fallen out of his breast pocket at that time.

One of Crowe’s assistants had Leopold put the glasses in his breast pocket and re-create the fall. The glasses did not fall out of the pocket. The questioning became more intense.

When questioned about his activities on the day of the murder, initially Leopold was vague. Finally, he admitted that he had spent most of the day with his friend Richard Loeb, eating, drinking and looking for birds in Lincoln Park. After dinner, they picked up two girls and drove around until they went to Leopold’s house where his aunt and uncle were waiting to be driven home.

As he was pressed for detail after detail, Leopold answered quickly and calmly. The inquisitors turned to questions about his personal life. In 1923, he had been graduated from the University of Chicago and had been attending law school. He planned to attend Harvard Law School later that year. He was very accomplished in the study of languages, was fluent in five and familiar with fifteen foreign languages.

He owned a Hammond Multiplex typewriter which the police confiscated and agreed that he had sufficient education to have composed the ransom note. He also agreed that the note did contain some legal wording, although it was not written by a lawyer.

Leopold had not known the Franks family, but had been following the case just like everyone else in Chicago.

After police had confiscated some of his letters, Leopold admitted that he had planned to translate the works of an Italian writer who wrote about acts of sexual perversion. However, he said he had never engaged in any sexual acts with his friend Richard Loeb.

Leopold was questioned until 4 A.M., after which he was taken to the police station to sleep until the next round of questioning. He did not realize it but his friend Richard Loeb had been picked up for questioning shortly after Leopold had been. Like Leopold, Loeb was being interrogated in another room in the LaSalle Hotel.

Loeb told a different story than Leopold about their activities on the day of Bobby Franks’ murder. He said that he was with Leopold during the afternoon, but stated that they parted at dinnertime. Loeb didn’t remember what he did the night of the murder.

Unsuspectingly, a mutual friend of the two boys delivered a critical message from Leopold to Loeb: “Babe [Leopold] said to tell the truth about the two girls. Tell the police what you did with them. You can’t get in any worse trouble than you are now. He said you’d understand.”

Suddenly, Loeb’s story and Leopold’s became the same. Some of the details were vague because Loeb said he had been drinking heavily and had forgotten.

Crowe and his assistants began to believe the boys’ story. The state’s attorney took them out for a lavish dinner. Afterward, the boys chatted amiably with the newspapermen. “I don’t blame the police for holding me,” Leopold told the Tribune. “I was at the culvert the Saturday and Sunday before the glasses were found and it is quite possible I lost my glasses there.”

Two other reporters knew that Leopold belonged to a law student study group. From the study group members, they learned that Leopold usually typed up the study sheets on his Hammond, but that at least once, he had used a portable typewriter. They got their hands on a couple of the study sheets that Leopold had prepared and compared them with the typing on the ransom note.

The typing from some of the study sheets was identical to the typing on the ransom note.

Leopold admitted that he may have typed on the portable, but denied owning the machine. His house was searched, but the portable was not found. The maid, however, remembered seeing a portable typewriter in the house several weeks earlier.

Crowe and his assistants kept digging. On May 31 they interviewed the Leopold’s chauffeur. On the day of the murder, the chauffeur had worked on Leopold’s car all day long. Furthermore, the chauffeur maintained that the car had been in the garage until late that evening when he went home. The boys had told the police that they had used Leopold’s car as they drove around the afternoon and evening of Bobby Franks’ death.

The police interrogated them intensely in separate rooms. When Loeb was confronted with the lie about the car, he asked who told them that. After hearing it was Leopold’s chauffeur, Loeb paled and asked to see Crowe.

Over the next two hours, a new story emerged.

Essentially, the whole murder/kidnap scheme was an elaborate game to entertain and intellectually challenge two bored students. They immensely enjoyed developing and refining what they were certain was the “perfect crime,” befitting their superior intellects. Collecting the ransom without being caught was a more difficult problem for them than the kidnapping and murder. They had put together several different plans for the ransom collection, researching each plan diligently.

Finally they agreed on the plan they would use. They would tell the boy’s father to go to a drugstore near the train station. They would call him at the drugstore and tell him to take a certain train that was leaving in a few minutes, so that the police could not be notified. On the train, the victim’s father would find a note in a prearranged place that would tell him where to throw the money from the train. The two boys would be waiting to retrieve it.

The kidnapping had been planned for a number of months, although the boys decided that they would select their victim the day of the kidnapping, as long as he had a rich father to pay the ransom. Also, the victim would have to be a person one of the boys knew so that it would be easy to lure him into the car. They had callously planned to murder the victim, so there was no concern about being identified. They would drive by the exclusive Harvard School and randomly select the boy that was most convenient.

At one point they had even considered kidnapping and murdering their fathers or brothers, but figured they would be under too much scrutiny if their own family was involved.

They understood that their victim would have to be killed quickly so that there was no chance of him escaping or being discovered. Once the victim was killed, disposal of the body was an immediate priority. The culvert at Wolf Lake was ideal because it was concealed enough that even Leopold was not initially aware of it, despite his frequent birding trips there. Also, by dropping the victim in the culvert, they avoided having to dig a grave.

Using one of their cars was out of the question since it could be traced back to them. They invented an elaborate scheme to rent a car under an assumed name. They covered the license plate, so even that could not be traced back to them.

The afternoon of the murder, Leopold and Loeb hung around the Harvard School after classes had finished. They had considered and rejected several students for various reasons. It was getting close to dinner time and most of the students had left. It was then that they saw Bobby Franks.

Richard knew Bobby. He was a neighbor and had played on the Loeb mansion’s tennis courts. Richard asked him to look at a particular tennis racket and Bobby agreed. As soon as he was in the car, Bobby was hit on the head with a chisel and a cloth forced down his throat, which led to his suffocation.

With Bobby dead or unconscious, covered by a rug in the backseat, the two boys drove toward the Indiana border. They pulled off on a deserted road and stripped the boy of his clothing, most of which they left by the side of the road.

They had dinner at a hot dog stand in Hammond and stayed there until it was almost dark. Then they took the dirt road to the marshlands around Wolf Lake. After dumping Bobby’s body into the culvert, they drove back home, stopping only so that Leopold could call his father to say he would be delayed and to call Jacob Franks to tell him his son had been kidnapped. At the same time, they addressed the ransom note to the Franks’ house and mailed it with postage and instructions for special delivery.

Then they went to Loeb’s house and burned clothes that had bloodstains on them. After that, they went to work on the bloodstains in the rental car. Later that night, the two boys stayed up late playing casino. They threw out the chisel used to murder Bobby on the way to take Loeb home.

The next day they perfected the scheme to collect the ransom money and placed the kidnap note in a telegraph box on the last car of a train going to Michigan City, Indiana. Then Leopold called Jacob Franks and gave him the address to the drugstore. When Jacob Franks didn’t go to the drugstore, they realized their grand scheme had failed.

Loeb ended his confession by saying,” I just want to say that I offer no excuse, but that I am fully convinced that neither the idea nor the act would have occurred to me had it not been for the suggestion and stimulus of Leopold. Furthermore, I do not believe that I would have been capable of having killed Franks.”

Confronted with Loeb’s confession, Leopold had little he could do but confess himself. The confessions were very similar except for some minor details and one major factor. Leopold claimed that Loeb had killed Bobby, whereas Loeb had claimed Leopold had committed the murder. Initially, the police and the press decided to believe Loeb and treat Leopold as the “evil genius” who had dominated his affable friend with his superior intellect.

In some ways, it didn’t matter which of the two had actually killed Bobby. They would both hang for premeditated murder and kidnapping, according to State’s Attorney Crowe.

The story of Leopold and Loeb dominated the newspapers. The Tribune explained why: “In view of the fact that the solving of the Franks kidnapping and death brings to notice a crime that is unique in Chicago’s annals, and perhaps unprecedented in American criminal history, the Tribune this morning gives to the report of the case many columns of space for news, comment, and pictures.

“The diabolical spirit evinced in the planned kidnapping and murder; the wealth and prominence of the families whose sons are involved; the high mental attainments of the youths, the suggestions of perversion; the strange quirks indicated in the confession that the child was slain for a ransom, for experience, for the satisfaction of a desire for “deep plotting,” combined to set the case in a class by itself.”

The public was aghast at the crime and the newspapers demanded swift retribution. “It should not be allowed to hang on, poisoning our thoughts and feelings. Every consideration of public interest demands that it be carried through to its end at once,” wrote the Herald and Examiner.

The story created tremendous anguish in the Jewish community. It had been unimaginable that such a crime could have been committed by the brilliant, cultured, pampered children of the Jewish social elite. These families represented society’s role models for success. Albert Loeb was a millionaire executive in charge of Sears, Roebuck’s prosperous mail-order business. Nathan Leopold, Sr., was a wealthy shipping and manufacturing executive. Both men were highly respected members of the community. Both were sympathetic figures. Albert Loeb, recovering from a serious heart attack, and Nathan Leopold, an elderly invalid, trying to cope with the horror that their sons had thrust upon them and their families.

Meyer Levin noted that “there was one gruesome note of relief in this affair. One heard it uttered only amongst ourselves a relief that the victim too had been Jewish. Though racial aspects were never overtly raised in the case, being perhaps eclipsed by the sensational suggestions of perversion, we were never free of the thought that the murderers were Jews.”

Once the ink on the confessions was dry, Crowe took the boys on a search for evidence. The clerk was found who sold Leopold the hydrochloric acid that he had poured on Bobby Franks’ body to disguise his features and circumcision. The chisel that killed the boy was retrieved from a man who had seen it thrown from the car. Bobby’s shoes that had been discarded on the side of the road were found after a long search. etc.

Crowe was very satisfied with the evidence they found that day. “We have the most conclusive evidence I’ve ever seen in a criminal case,” he announced.

During the day, Jacob Loeb, Richard’s uncle, and Benjamin Bachrach, a successful attorney, tried to find out where the boys were being held, but they were not told. The two boys were in desperate need of an attorney.

Later that evening, Jacob Loeb went to the apartment of the one of the country’s most brilliant lawyers. Loeb got the sixty-seven-year-old Clarence Darrow and his wife out of bed. Darrow had made a name for himself championing the underdog and fighting capital punishment.

“Get them a life sentence instead of death,” Loeb begged for his nephew and Leopold. “That’s all we ask. We’ll pay anything, only for God’s sake, don’t let them hang.”

Darrow took the case, not for the fee, but by defending these two boys, he had a unique opportunity to combat the death penalty. This case was getting so much publicity around the country and the world that it was a rare chance for him to be widely heard on his capital punishment soapbox.

The boys had already done irreparable harm to their defense, not only in their confessions, but in helping locate evidence that would be used against them and by running off at the mouth to their captors, newspapermen and anyone else who would give them an audience.

Leopold told one reporter, “Why, we even rehearsed the kidnapping at least three times, carrying it through in all details, lacking only the boy we were to kidnap and kill…It was just an experiment. It is as easy for us to justify as an entomologist in impaling a beetle on a pin.”

Loeb told the police captain, “This thing will be the making of me. I’ll spend a few years in jail and I’ll be released. I’ll come out to a new life.”

The police took careful notes and the newspapermen wrote furiously as the boys kept talking and talking.

Darrow was on the case the next day. Sunday, June 1, he waited with Jacob Loeb and Benjamin Bachrach until the boys had been returned from another evidence gathering expedition. They demanded to see the two boys, but were refused. Crowe had three traditional alienists forensic psychiatrists lined up to interview the boys that afternoon to confirm that they were indeed sane as well as guilty.

Early the next morning, Darrow and Bachrach were in Crowe’s office demanding that the two boys be moved to the county jail where he and Bachrach and their families could see them. Again Crowe refused so that his alienists could get additional evidence of their sanity. Crowe assumed that Darrow would plead them not guilty by reason of insanity and he wanted to be sure that the prosecution had enough evidence of the boys’ sanity before their lawyers cut off their damaging testimony.

However, Darrow had with him an order from Judge John R. Caverly. The boys were allowed to meet with their attorneys before being confined in the country jail.

“Be polite. Be courteous, ” Darrow told them. “But don’t give Crowe any more help. Just keep quiet and refuse to answer questions.”

Pampered in everyday life, the boys were also pampered in jail. Stein’s Restaurant catered to their need for good food, cigarettes and liquor, which was sneaked into them since it was Prohibition times.

On June 5, 1924, the grand jury indicted the two boys on eleven counts of murder and sixteen counts of kidnapping. The very next day, their full confessions were published in the newspapers. The public was incensed, not just over the crime itself, but the perception, fanned by the news media, that the wealthy Loebs and the wealthy Leopolds were going to pay Clarence Darrow a million dollars to save their sons from the gallows.

With Darrow’s help, the families constructed a joint statement, which in summary said, “There will be no large sums of money spent, either for legal or medical talent.”

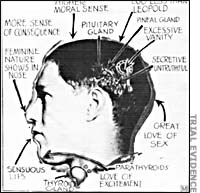

Walter Bachrach, Benjamin’s brother, promptly went to the American Psychiatric Association’s annual convention and recruited three top flight experts: Dr. William A. White, president of the APA and superintendent of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C.; Dr. William Healy, an expert in juvenile criminal psychiatry; and Dr. Bernard Glueck, head of the psychiatric clinic at Sing Sing Prison in New York State. Unlike Crowe’s traditional alienists, Bachrach’s experts were innovative Freudians who believed in subconscious motives and compulsions. Two other psychiatrists were also employed, Dr. Harold Hulbert and Dr. Carl Bowman.

Leopold loved the sessions with the alienists. His ego was intensely gratified that these experts were putting his personality under a microscope. It also gave him a chance to talk continuously about himself. Loeb, on the other hand, was bored with the entire process and occasionally fell asleep. Neither boy showed any guilt or remorse for their cold-blooded crime, though both of them were upset that they had brought down so much misery on their families.

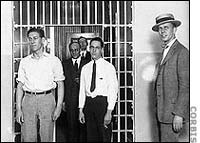

On July 21, 1924, the case of The People against Nathan Leopold, Jr., and Richard Loeb opened in Chief Justice of the Criminal Court John R. Caverly’s courtroom.

Darrow approached the bench and began to speak in a low voice. First he assured the court that he was not going to try to have the trial moved somewhere else, nor was he going to try to stop the prosecutors from separating the murder indictments from the kidnapping indictments.

“We want to state frankly here that no one in this case believes that these defendants should be released or are competent to be. We believe that they should be permanently isolated from society… After long reflection and thorough discussion, we have determined to make a motion in this court for each of the defendants in each of the cases to withdraw our pleas of not guilty and enter a plea of guilty.”

Everyone in the courtroom was shocked. They had expected Darrow to plead them not guilty by reason of insanity.

Darrow had planned this for some time and discussed it with the families, but did not tell the boys until that morning. The boys understood that it was their best chance to escape hanging. He explained it to them this way, “Crowe had you indicted both for murder and for kidnapping. He’d try you on one charge, say, the murder. If he got less than a hanging verdict, he could turn around and try you on the other charge. There is only one way to deprive him of that second chance to plead guilty to both charges before he…has an opportunity to withdraw one of them. That’s why the element of surprise is absolutely necessary.

There was more to Darrow’s rationale. In pleading guilty, the boys could avoid a jury trial. A single judge would determine the sentence. Had he chosen to plead them not guilty by reason of insanity, they would have had a jury trial. Given the public outcry over the crime and the statements the boys had made, it was unlikely that the boys would fare well with any jury.

Darrow realized that it was comparatively easy for a jury to sentence the boys to death because it would be a shared decision. For Caverly to sentence the boys to death was a decision that he would have to live with as solely his own. He felt that he had a decent chance with Caverly considering the boy’s mental conditions and their youth.

Caverly told the defendants to approach the bench and questioned each boy: “if your plea be guilty, and the plea of guilty is entered into this case, the court may sentence you to death; the court may sentence you to the penitentiary for the term of your natural life; the court may sentence you to the penitentiary for a term of years not less than fourteen. Now, realizing the consequences of your plea, do you still desire to plead guilty?”

Both boys answered “yes.” They were beginning to understand the magnitude of their predicament.

Judge Caverly, looking very serious, was beginning to understand the magnitude of his predicament. He alone would decide whether or not the boys would hang. It was not a decision he wanted to make.

The hot, stuffy courtroom held only 300 people, 200 of which were representatives of the news media. Only seventy spaces were allotted for spectators.

Judge John R. Caverly was scholarly man of sixty-three years. Born to English immigrants, he worked his way through college and law school by working in the steel mills. Nearly at the end of his career when this trial began, he had imposed the death sentence fixed by juries five times in his time on the bench.

State’s Attorney Robert E. Crowe made the opening statement: “The evidence in this case will show that Nathan Leopold, Jr., is a young man nineteen years old, that the other defendant, Richard Loeb, is a young man of nineteen years; that they are both sons of highly respected and prominent citizens of this community; that their parents gave them every advantage wealth and indulgence could give to boys. They have attended the best schools in this community and have, from time to time, had private tutors. These young men behaved as a majority of young men in their social set behaved, with the exception that they developed a desire to gamble, and gambled, for large stakes, the size of the stakes being such that even their wealthy companions could not sit with them.

“The evidence will further show that along in October or November of last year these two defendants entered into a conspiracy, the purpose of which was to gain money, and in order to gain it they were ready and willing to commit a cold-blooded murder.”

An hour later, he concluded his statement with, “in the name of the people of the State of Illinois, in the name of the womanhood and the fatherhood, and in the name of the children of the State of Illinois, we are going to demand the death penalty for both of these cold-blooded, cruel, and vicious murderers.”

“The Old Lion,” as Darrow was called, responded to the prosecution. “We shall insist in this case, Your Honor, that, terrible as this is, terrible as any killing is, it would be without precedent if two boys of this age should be hanged by the neck until dead, and it would in no way bring back Robert Franks or add to the peace and security of this community.

The prosecution began bringing forward its witnesses before Judge Caverly. Their strategy was to present every detail to stress the horror of the crime. There was almost no cross-examination by the defense since it would have underscored the brutality of the crime.

The boys continued to be light hearted despite the hangman’s noose that swung over their heads. The next day, Thursday, July 23, before the court convened, Loeb told the reporters he had an important statement to make: “We are united in one great and profound hope for today,” Loeb said pompously. “Mr. Leopold and I have gone over the matter and have come to a mutual decision. We have just one hope: that it will be a damned sight cooler than it was yesterday.” He burst into laughter.

A week and eighty-one witnesses later, Crowe rested his case. He had proven the boys’ guilt beyond a doubt. Of course, the boys had already pleaded guilty, so the entire week simply belabored the obvious.

Darrow’s strategy was to use the testimony of the alienists (forensic psychiatrists) to mitigate the death penalty.

Doctors Hulbert and Bowman studied every single detail of the lives of Leopold and Loeb and compiled it into an exhaustive report of some 300 pages of official transcript. The report was made to “determine whether or not insanity was a justifiable plea for the defense.” Most importantly it set out to discover why these two boys killed Bobby Franks.

It became clear in this report that Richard Loeb had criminal tendencies that began to exhibit themselves at the age of 8 or 9.

Loeb stole money and objects with “absolutely no compunction of guilt or fear connected with this theft…but felt ashamed [when] his lack of skill caused him to be caught.” Stealing and shoplifting for the thrill of it, rather than the desire for the object taken, continued unabated through his teenage years.

Leopold’s role in Loeb’s life was as an accomplice to his criminal acts. In exchange for limited homosexual favors (Leopold was allowed at certain intervals to insert his penis between Loeb’s legs), Loeb drew Leopold into criminal acts which escalated in seriousness.

Stealing small objects graduated into stealing and vandalizing cars. Making annoying phone calls to school instructors graduated into turning in false fire alarms which then graduated into arson. In 1923, they planned a burglary of a friend’s home when the family was away, taking with them a revolver to shoot the nightwatchman and ropes to tie up the maid if it became necessary. Fortunately, the engine of their car broke down and the plan was abandoned. Instead, they burglarized Loeb’s Zeta Beta Tau fraternity house in Ann Arbor.

The Hulbert-Bowman report was “stolen” over the weekend and was widely published on Monday, July 26.

When the defense opened its case, by calling Dr. William Alanson White, head of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. and president of the American Psychiatric Association, Crowe objected strenuously. “You do not take a microscope and look into a murderer’s head to see what state of mind he was in, because if he is insane he is not responsible, and if he is sane, he is responsible. You look not to his mental condition, but to the facts surrounding the case did he kill the man because the man debauched his wife? If that is so, then there is mitigation here…But here is cold-blooded murder, without a defense in fact,and the attempt on a plea of guilty to introduce an insanity defense before your honor is unprecedented. The statute says that is a matter that must be tried by a jury.”

Darrow rebutted: “The statute in this state provides that the court may listen to anything, either in mitigation of the penalty or in aggravation.”

Actually, there was virtually no precedent in this matter. Several days of legal arguments ensued.

At the end of that period, Darrow began to state his argument in the style and substance that made him one of the greatest lawyers ever: “Now, I understand that when everything has been said in this case from beginning to end, the position of the state’s attorney is that the universe will crumble unless these boys are hanged. I must say that I have never before seen the same passion and enthusiasm for the death penalty as I have in this case, and there have been thousands of killings before this, much more horrible in details…There have been thousands before, and there will probably be thousands again, whether these boys are hanged or go to prison. If I thought that hanging them would prevent any future murders, I would probably be in favor of doing it. But I have no such feeling….

“What is a mitigating circumstance? Is it youth? If so, why? Simply because the child has not the judgment of life that a grown person has…

“Here are two boys who are minors. The law would forbid them making contracts, forbid them marrying without the consent of their parents, would not permit them to vote. Why? Because they haven’t the judgment which only comes with years, because they are not fully responsible…

“I cannot understand the glib, lighthearted carelessness of lawyers who talk of hanging two boys as if they were talking of a holiday or visiting the races…”

Darrow then looked at Judge Caverly and his voice hushed in respect, “I don’t believe there is a judge in Cook County that would not take into consideration the mental status of any man before they sentence him to death.”

Finally, Caverly agreed to hear evidence in mitigation. Darrow had won a key victory. The defense alienists could now be called to testify and the already well-known report of Doctors Hulbert and Bowman could be put into the court record.

Some of the information and analysis was part of the trial testimony, but all of it was part of the trial record, and was thoroughly read by Judge Caverly, whose opinion on the psychiatric findings was the only one that counted. In total, the alienists’ reports give valuable insight into the family lives and social environment in which these two boys lived. They also provided an appreciation of the boys’ values and morals, which were at odds with those of their families and friends.

When it came to Richard Loeb’s parents, the alienists wrote: “Albert H. Loeb is fair and just. He is opposed to the boys’ drinking and often spoke of it; he is not strict, although the boys may have thought he was. He never used corporal punishment. In early childhood, he was not a play-fellow with the boys…Dick and his brothers loved and worshipped their father and did not want to lose their father’s love and respect.”

Ann Bohnen Loeb was from a large Catholic family, which did not approve of her marriage to a Jew, despite his very high social standing and wealth. However, the Albert Loeb’s friends fully accepted her and thought well of her. Together, she and Albert had four sons: Allan, Ernest, Richard and Thomas. The alienists considered Ann “poised, keen, alert and interested.”

While much of what the alienists said about Richard Loeb describes a purely psychopathic personality, there are events in Richard’s life that show another side to him. Maureen McKernan tells the story in The Amazing Crime and Trial of Leopold and Loeb of Richard’s automobile accident: “The summer he was fifteen years old, driving to a dance one evening at dusk, his automobile collided with a horse and buggy at a dark street corner. He had not yet turned on the automobile lights and the accident was said to be unavoidable. A woman was hurt and her grandson slight injured. Dick helped take her to the hospital, but, once there, when he realized she was injured, he wept and fainted. He had to be almost carried home. Every day he visited the woman, taking her flowers and fruit, and the best of food. He persuaded his father, not only to pay all the hospital bills, but to pay off a mortgage on the woman’s home, and to send her on a trip that winter to mend her shattered nerves.”

At the age of four, a Canadian woman named Struthers became his governess. She devoted an enormous amount of time to his education coaching, tutoring and encouraging him to study. Richard was a very bright lad whose IQ was 160 and she was very successful in getting Richard promoted rapidly in school. He finished grade school at age twelve, graduated from high school at fourteen and entered the University of Chicago that year. After an argument with Mrs. Loeb, Miss Struthers left the household.

The alienists interviewed her and decided that she was “too anxious to have him become an ideal boy….She would not overlook some of his faults and was too quick in her punishment and therefore he built up the habit of lying without compunction and with increasing skill. She was quite unaware of the fact that he had become a petty thief and a play detective.”

Wanting to get away from home, Richard transferred to the University of Michigan and was one of their youngest graduates at age seventeen. Richard was lazy and unmotivated, so his grades were nothing special, despite his high intelligence.

Loeb’s extensive education did not include sex, which Miss Struthers did not broach to him as a subject. Consequently, Richard learned the basics from conversations with the family chauffeur. Sex did not become important to him and he believed that he was less sexually potent than his friends. His good looks, sophistication, wealth and social graces allowed him many opportunities with the opposite sex. While he took advantage of these opportunities, neither sex nor an enduring relationship with a woman was a high priority for him.

Lying was an integral part of Richard’s personality and he was very accomplished at it. While he admitted that lying was wrong, he felt no guilt about doing it. His overactive fantasy life focused on him as the master criminal. He wanted to commit one perfect crime and then quit.

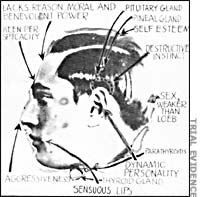

Dr. White summarized the nineteen-year-old Loeb in court: “All of Dickie’s life, from the beginning of his antisocial activities, has been in the direction of his own self-destruction. He himself has definitely and seriously considered suicide. He told me that he was satisfied with his life and that so far as he could see, life had nothing more to offer, because he had run the gamut. He was at the end of the situation He had lived his life out.” White saw infantilism as Loeb’s outstanding characteristic. He believed that Richard was the one who actually murdered Bobby.

Dr. Healy did not think much of Loeb at all: lazy, unmotivated, shallow, but with an affable and outgoing personality. “To my mind the crime itself is the direct result of diseased motivation of Loeb’s mental life. The planning and commission was only possible because he was abnormal mentally, with a pathological split personality.

Dr. Glueck was fascinated by Loeb. “I was amazed at the absolute absence of any signs of normal feelings, such as one would expect under the circumstances. He showed no remorse, no regret, no compassion for the people involved in this situation….He told me the details of the crime, including the fact that he struck the blow.” This testimony was the most revealing clue at that time as to which one of the boys actually committed the murder.”

Nathan Leopold was the boy to whom the alienists were most sympathetic. He was the youngest of four sons and acquired the nickname of Babe. He had been a sickly boy, suffering from a number of glandular problems: hyperthyroidism, a calcified pineal gland and related difficulties. He had not been expected to reach an old age.

His mother died from nephritis when he was seventeen. She had never recovered her health after his birth, a fact for which Nathan felt the blame. After his mother’s death, his maternal aunt, Mrs. Birdie Schwab, who lived in the neighborhood, managed the household.

Nathan was a genius with an IQ of 210. Supposedly he spoke his first words at four months of age.

There were several governesses, all of whom had their hands full with four boys. Nathan Leopold, Sr., a successful businessman, left the raising of the children to Aunt Birdie and the governesses.

Nathan went to the Harvard School where he was not particularly popular. His extraordinary intelligence made him feel superior to his classmates, a fact that he impressed upon them repeated. His schoolmates considered him supercilious and conceited.

When he was sixteen, he went to the University of Chicago along with Richard Loeb. When Loeb transferred to the University of Michigan, Leopold followed him. But Richard was involved in his fraternity and kept Nathan at bay. Zeta Beta Tau had accepted Richard with the provision that he not hang around with Leopold and thereby quash rumors of homosexuality. Nathan returned to Chicago and graduated Phi Beta Kappa. He began law school at the same university.

The alienists noted that Leopold “does not make friends very easily and he has especial difficulty in getting along with the opposite sex.” The only sexual relations he had were with women prostitutes. He had never really been attracted to women and considered them to be inferior intellectually.

His mother’s death had a very profound effect on him. He could not reconcile the suffering of his mother with a belief in God and became an atheist after her death.

The alienists considered Leopold to be truthful and frank, compared to Richard. “The patient makes no effort to shift the blame for the crime to his companion, although he insists that he did not desire to commit the crime and derived no special pleasure from it. He feels that his only reason for going into it was his pact of friendship with his companion, and his companion’s desire to do it….Since he had a marked sex drive, and has not been able to satisfy it in the normal heterosexual relations, this has undoubtedly been a profound upsetting condition on his whole emotional life…he endeavored to compensate for [his physical inferiority] by a world of fantasy in which his desire for physical perfection could be satisfied. We see him therefore fantasizing himself as a slave, who is the strongest man in the world.” The slave fantasies began at the age of five and continued throughout his youth: “In some way or other [in these fantasies]…he saved the life of the king. The king was grateful and wanted to give him his liberty, but the slave refused.”

Leopold jumped at any opportunity to discuss his philosophy with the alienists, so they were quite familiar with it when they wrote their report: “In such a philosophy, without any place for emotions and feelings, the intelligence reigns supreme. The only crime that he can commit is a crime of intelligence, a mistake of intelligence, and for that he is fully responsible…In the scheme of the perfect man which he drew up, he gave Dickie a scoring of 90, himself a scoring of 63, and various other of their mutual acquaintances various marks ranging from 30 to 40.

Dr. White viewed the Franks murder as the result of the boys’ abnormal personalities and fantasies: “Dickie needed an audience. In his fantasies the criminalistic gang was his audience. In reality, Babe was his audience….Babe’s tendencies could be expressed as they were in the king-slave fantasy as a constant swing between a feeling of [physical] inferiority and one of [intellectual] superiority….[Leopold] is the slave who makes Dickie the king, maintains him in his kingdom…I cannot see how Babe would have entered into it at all alone because he had no criminalistic tendencies in any sense as Dickie did, and I don’t think Dickie would have ever functioned to this extent all by himself. So these two boys, with their peculiarly inter-digited personalities, came into this emotional compact with the Franks homicide as a result.

Dr. Healy elaborated on this compact between the boys: “Leopold was to have the privilege of inserting his penis between Loebs’ legs at special dates. At one time it was to be three times in two months if they continued their criminalistic activities together.”

Dr. Healy considered Leopold as having a paranoid personality. Listening to Nathan’s statement that “making up my mind whether or not to commit murder was practically the same as making up my mind whether or not I should eat pie for supper, whether it would give me pleasure or not,” apparently shocked the veteran forensic psychiatrist.

Dr. Glueck emphasized Leopold’s embrace of the Nietzschean concept of the Superman. Like the other alienists, Glueck saw the murder as the result of the two abnormal personalities working together: “I think the Franks crime was perhaps the inevitable outcome of this curious coming together of two pathologically disordered personalities, each one of whom brought into the relationship a phase of their personality which made their contemplation and the execution of this crime possible.”

When Crowe asked for his opinion on the motivation for the crime, he responded, “I don’t know that there was a direct motive for this crime. I do feel that Loeb had in his mind probably the motive of complete power, potency, the realization of the fantasy of a perfect crime.”

“How about Leopold,” Crowe asked.

“I don’t know that he had any.”

The highpoint of the trial was Clarence Darrow’s speech on August 22, 1924. It lasted for two hours and was considered the finest of his long career.

Near the beginning of the speech, he stressed that “never had there been a case in Chicago, where on a plea of guilty a boy under twenty-one had been sentenced to death. I will raise that age and say, never has there been a case where a human being under the age of twenty-three has been sentenced to death….Why need the state’s attorney ask for something that never before has been demanded?

“I know that in the last ten years four hundred and fifty people have been indicted for murder in the city of Chicago and have pleaded guilty….and only one has been hanged! And my friend who is prosecuting this case deserves the honor of that hanging while he was on the bench. But his “victim” was forty years old.”

Later, Darrow took issue with the constant use by the prosecution of the term “cold-blooded murder.” Darrow put this rhetoric in perspective: “They call it a cold-blooded murder because they want to take human lives….This is the most cold-blooded murder, says the State, that ever occurred….I have never yet tried a case where the state’s attorney did not say that it was the most cold-blooded, inexcusable, premeditated case that ever occurred. If is was murder, there never was such a murder…Lawyers are apt to say that.”

He took head-on the issue of whether it really was a cold-blooded murder and the most terrible murder that ever happened in Illinois. “I insist, Your Honor, that under all fair rules and measurements, this was one of the least dastardly and cruel of any that I have known…Poor little Bobby Franks suffered very little….It was all over in fifteen minutes after he got into the car, and he probably never knew it or thought of it. That does not justify it….But it is done.

“This is a senseless, useless, purposeless, motiveless act of two boys….There was not a particle of hate, there was not a grain of malice, there was no opportunity to be cruel except as death is cruel — and death is cruel.”

Darrow trashed the silly motivation that Crowe had ascribed to the crime: that the murder was committed so that each boy could get $5,000 in ransom money. Loeb had $3,000 in his checking account at the time of the murder and his father gave him money any time he wanted it. Leopold’s father was about to give him $3000 for a trip to Europe.

Crowe had mentioned that the boys had run up huge gambling debts playing bridge. The huge gambling debt consisted of $90 which one boy lost to the other. “It would be trifling, excepting, Your Honor, that we are dealing in human life. And we are dealing in more than that; we are dealing in the future fate of two families.

“We are talking of placing a blot upon the escutcheon of two houses that do not deserve it. And all that [the State] can get out of their imagination is that there was a game of bridge and one lost ninety dollars to the other, and therefore they went out and committed murder.”

He summed up the bizarre mental states of the two boys and the tragic result of their friendship: “They had a weird, almost impossible relationship. Leopold, with his obsession of the superman, had repeatedly said that Loeb was his idea of the superman. He had the attitude toward him that one has to his most devoted friend, or that a man has to a lover. Without the combination of these two, nothing of this sort probably would have happened….all the testimony of the alienists….shows that this terrible act was the act of immature and diseased brains, the act of children.

“Nobody can explain it any other way.

“No one can imagine it any other way.

“It is not possible that it could have happened in any other way.”

He ended his summation with a dramatic plea for the boys’ lives:

“I do not know how much salvage there is in these two boys. I hate to say it in their presence, but what is there to look forward to? I do not know but that Your Honor would be merciful if you tied a rope around their necks and let them die; merciful to them, but not merciful to civilization, and not merciful to those who would be left behind. To spend the balance of their lives in prison is mighty little to look forward to, if anything….So far as I am concerned, it is over….And I think here of the stanza of Housman:

‘Now hollow fires burn out to black,

‘And lights are fluttering low:

‘Square your shoulders, lift your pack

‘And leave your friends and go.

‘O never fear, lads, naught’s to dread,

‘Look not left nor right:

‘In all the endless road you tread

‘There’s nothing but the night.’

“I care not, Your Honor, whether the march begins at the gallows or when the gates of Joliet close upon them, there is nothing but the night, and that is little for any human being to expect…..

“None of us are unmindful of the public; courts are not, and juries are not. We placed our fate in the hands of a trained court, thinking that he would be more mindful and considerate than a jury. I cannot say how people feel. I have stood here for three months as one might stand at the ocean trying to sweep back the tide. I hope the seas are subsiding and the wind is falling, and I believe they are, but I wish to make no false pretense to this court.

“The easy thing and the popular thing to do is to hang my clients. I know it. Men and women who do not think will applaud. The cruel and thoughtless will approve. It will be easy today; but in Chicago, and reaching out over the length and breadth of the land, more and more fathers and mothers, the humane, the kind and the hopeful, who are gaining an understanding and asking questions not only about these poor boys, but their own these will join in no acclaim at the death of my clients. They would ask that the shedding of blood be stopped, and that the normal feelings of man resume their sway. And as the days and the months and the years go on, they will ask it more and more.

“But, Your Honor, what they shall ask may not count. I know the easy way. I know Your Honor stands between the future and the past. I know the future is with me, and what I stand for here; not merely for the lives of these two unfortunate lads, but for all boys and girls; for all of the young, and as far as possible, for all of the old. I am pleading for life, understanding, charity, kindness, and the infinite mercy that considers all. I am pleading that we overcome cruelty with kindness, and hatred with love. I know the future is on my side…

“I feel that I should apologize for the length of time I have taken. This case may not be as important as I think it is, and I am sure I do not need to tell this court, or to tell my friends that I would fight just as hard for the poor as for the rich. If I should succeed in saving these boys’ lives and do nothing for the progress of the law, I should feel sad, indeed. If I can succeed, my greatest reward and my greatest hope will be that I have done something for the tens of thousands of other boys, for the countless unfortunates who must tread the same road in blind childhood that these boys have trod; that I have done something to help human understanding, to temper justice with mercy, to overcome hate with love.”

The prosecution’s closing took two days.

On Wednesday, September 19, 1924, Judge Caverly announced his decision. He agreed that a case could not be made for the boys being insane, however he stated that “they have been shown in essential respects to be abnormal; had they been normal they would not have committed the crime.” He went on to recognize that the detailed reports of the alienists would be a valuable contribution to criminology.

“The testimony in this case reveals a crime of singular atrocity. It is in a sense, inexplicable; but it is not thereby rendered less inhuman or repulsive.”

Caverly went on to summarize the possible penalties for murder and kidnapping before giving his sentence.

“It would have been the path of least resistance to impose the extreme penalty of the law. In choosing imprisonment instead of death, the court is moved chiefly by the consideration of the age of the defendants…Life imprisonment may not, at the moment, strike the public imagination as forcibly as would death by hanging; but to the offenders, particularly of the type they are, the prolonged suffering of years of confinement may well be the severer form of retribution and expiation.

Caverly urged the department of public welfare never to admit these defendants to parole.

“For the crime of murder, confinement at the penitentiary at Joliet for the term of their natural lives.

“For the crime of kidnapping for ransom, similar confinement for the term of ninety-nine years.”

At the end of the trial, Jacob Franks had reversed his earlier call for hanging: “My wife and I never believed Nathan, Jr., and Richard should be hanged.”

The impact of the trial on the principals was very severe. Nobody close to the case would ever be the same afterwards.

Both Judge Caverly and his wife immediately checked themselves into a hospital to recover from the enormous strain and exhaustion of the trial. When he returned to the bench, he arranged to hear only divorce cases. “My health has been sapped,” he told reporters.

Jacob Franks died a few years later and never recovered from the grief of losing his youngest son. Flora, Bobby’s mother, who was delusional after her son’s death and during the trial, did eventually recover her wits. She eventually remarried after her husband’s death.

Albert Loeb, who had been invalided by a severe heart attack before his son’s crime and spent the entire trial trying to stay alive at his country estate in Charlevoix, died a month after his son was sentenced. He never saw his son after he had been arrested in May.

Nathan Leopold’s father died of heart failure in 1929. Shame and sorrow had driven him from his home in Kenwood. Two of his sons changed their last names to rid themselves of the family scandal.

Clarence Darrow went on to one more big case: the Scopes “Monkey” trial where he defended a Tennessee schoolteacher for teaching evolution. The “silver-tongued” orator, William Jennings Bryan, was his opponent.

At first, prison officials tried to keep Leopold and Loeb apart, but eventually they ended up together. Their lives were drastically altered. A year later, when reporters came to see them, Leopold refused to be interviewed. Loeb was much altered. “I can’t talk to you. I’d like to say something, but I’m afraid I’ll get in bad.”

In 1932, the two of them opened a school for the prisoners. Along with other educated inmates, Leopold and Loeb did the administrative work and taught classes. Both of them showed signs of rehabilitation. For once they were doing something really constructive with their lives, their intellectual gifts and their expensive educations

But prison is a very dangerous place to live, despite the illusion of security. On January 28, 1936, James E. Day, Loeb’s cellmate attacked him in the shower with a straight razor. Blood poured out from over fifty razor wounds. Seven doctors and surgeons fought to save him, but Richard Loeb died at the age of thirty-two from loss of blood and shock. Afterwards, Leopold washed the blood from the body of his most intimate friend.

Later in Leopold’s book Life Plus 99 Years, he describes his feelings: “We covered him at last with a sheet, but after a moment, I folded the sheet back from his face and sat down on a stool by the table where he lay. I wanted a long last look at him.

“For, strange as it may sound, he had been my best pal.

“In one sense, he was also the greatest enemy I have ever had. For my friendship with him had cost me my life. It was he who had originated the idea of committing the crime, he who had planned it, he who had largely carried it out. It was he who had insisted on doing what we eventually did…Dick was a living contradiction.

“As I sat now by his cooling, bleeding corpse, the strangeness of that contradiction, that basic, fundamental ambivalence of his character, was borne in on me.

“For Dick possessed more of the truly fine qualities than almost anyone else I have ever known. Not just the superficial social graces. Those, of course, he possessed to the nth degree….But the more fundamental, more important qualities of character, too, he possessed in full measure. He was loyal to a fault. He could be sincere; he could be honestly and selflessly dedicated. His devotion to the school proves that. He truly, deeply wanted to help his fellow man.

“How, I mused, could these personality traits coexist with the other side of Dick’s character? It didn’t make sense! For there was another side. Dick just didn’t have the faintest trace of conventional morality. Not just before our incarceration. Afterward too. I don’t believe he ever, to the day of his death, felt truly remorseful for what we had done. Sorry that we had been caught, of course….But remorse for the murder itself? I honestly don’t think so.”

James Day claimed that he delivered those fifty plus razor wounds because Loeb had made homosexual advances to him. This was highly unlikely since Loeb’s throat was slashed from behind. Day and Loeb had many arguments before usually related to Day’s portion of the money that Loeb gave out to his friends for cigarettes and candy. Out of the $50 monthly allowance that Loeb’s family provided him, he completely supplied Day and others with snacks and tobacco. When the new warden cut each prisoner’s allowance to $3/week, Day was jealous that he wasn’t getting from Loeb what he thought he should.

Day, of course, did not have a scratch on him, despite his plea that he had killed Loeb in self-defense. The blood on Day’s body was Richard’s. Regardless of the facts, Day was judged not guilty.

Leopold, not surprisingly, devoted a great deal of his time in prison to learning. In addition to the fifteen languages he had learned before he went to prison, he mastered twelve more. He studied mathematics and other more arcane subjects. He continued his work in the prison school and library, raised canaries and volunteered in the malaria project.

After many years of shunning the press, he decided eventually to rehabilitate his public image by careful cultivation of the press. It paid off after a while and in 1953 he had a parole hearing. The State’s Attorney, John Gutknecht, was so opposed to Leopold’s parole that he vigorously lobbied against it.

The result was that not only was Leopold turned down, but the parole board decided not to hear his case again for twelve years, the longest continuance in history of Illinois.

Finally in March of 1958, after thirty-three years in prison, Leopold was released on parole. He went to live in Puerto Rico to avoid harassment by the press. There he published The Birds of Puerto Rico, obtained a masters degree at the University of Puerto Rico and worked at various positions.

In 1961, Leopold married Trudi Feldman Garcia de Queveda, a former social worker from Baltimore and widow of a Puerto Rican physician. Ten years later, in 1971, he died of a heart attack at the age of sixty-six with his wife by his side.

Books on the Leopold and Loeb case are not easy to find or buy. This feature story is particularly indebted to several books and the Chicago Tribune: Hal Higdon’s very thorough Crime of the Century: The Leopold & Loeb Case (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1975) is highly recommended and was used frequently in the creation of this Crime Library story. Unfortunately, it is out of print and is not easy to find in libraries. Also used as a major source for this story is Kevin Tierney’s Darrow: A Biography (Thomas Y. Crowell, 1979) and Classics of the Courtroom, Volume VIII, “Clarence Darrow’s Sentencing Speech in State of Illinois v. Leopold and Loeb.

Other resources used:

Levin, Meyer, Compulsion. Simon & Schuster, 1956. Fiction

Leopold, Nathan F., Jr., Life Plus 99 Years. Doubleday, 1958

McKernan, Maureen, The Amazing Crime and Trial of Leopold and Loeb. New American Library, 1957.