D.C. Starbucks shooter Carl Cooper murdered three young people — Routines Shattered — Crime Library

The dayshift manager arrived to open the Starbucks Coffee Shop at 1810 Wisconsin Avenue, on the border of the upscale Burleith and Georgetown neighborhoods of Washington, D.C., at 5:15 A.M on a hot Monday morning, July 7, 1997. The long Fourth of July weekend, always hectic for the Washington, D.C., area, was over. Nevertheless, the shop would be busy soon with commuters returning to work. She had to hurry.

The manager noticed a lone car with a flat tire in the parking lot, which seemed strange. It resembled the one that ‘Caitrin’, the nightshift supervisor, drove. Maybe she’d seen the flat and asked someone to drive her home. The area was safe enough to leave a car overnight.

Letting herself in, the manager saw with dismay that the place was still littered with trash. As she walked through the eating area, it seemed that something more was amiss than the nightshift’s simple neglect. The store’s music was still playing; seemingly no one had shut it off. It was out of character for Mary Mahoney to leave without ensuring that everything was as it should be. She was conscientious to a fault. The place just felt wrong: a stray cup on the floor, a broom leaning against the counter, the garbage not taken out, as if the cleanup had just suddenly stopped.

The manager continued to look around, uncertain what to make of the unkempt area, and then entered the back room to open the office. There she saw a female form in a Starbucks uniform lying on the floor. It was Mary Catherine Mahoney, and she lay disturbingly still. Around her was a dark liquid substance that looked like blood. Just beyond her, someone else was on the floor, and now it seemed clear that these two employees had been killed.

Running from the store onto the empty sidewalk, the manager flagged down a bus driver, according to The Washington Post, to ask for help. She was not about to remain in the shop to make an emergency call. The driver did it for her, alerting dispatchers at 911 to send the police. They responded right away.

A team of officers arrived to protect and examine the scene. Taping the entrance, they kept customers out but started to draw a curious crowd. Officers found the bodies of not two but three uniformed employees on the floor in the back room, one of them lying partially over another. All had been shot and their blood had pooled onto the floor around them. A detective checked with the manager who had first found them and she said that when she had arrived the doors were locked. Yet there had been no forced entry, and the keys were still with Caitrin. Since closing time was 8:00 p.m. on Sundays, it seemed likely that the perpetrator had arrived before the doors were locked. The condition of the bodies indicated a time of death near to this.

A crime scene processing unit arrived to take photographs, lift fingerprints, look for other types of evidence, and map the scene. They picked up ten bullet casings, some from a .38 revolver and others from a .380 semiautomatic handgun, so they surmised that two shooters had been involved.

Detectives fanned out to canvass the neighborhood for witnesses and leads. They found someone who had tried the door between 9:00 and 9:30 p.m., and said they had been open. Since the doors were locked when the dayshift supervisor came in, it seemed possible that the killers were still there between 9:00 and 9:30. Yet the casings left behind indicated a hurried or careless exit.

The two other victims, both male, were Emory Allen Evans, 25, and Aaron David Goodrich, 18. Goodrich had only worked there a few months and had been a last-minute addition to the Sunday evening shift. Evans had been employed there less than a month.

The assumption was that the deaths had occurred in the course of a robbery. While Burleith was considered a safe residential neighborhood, there had been a spate of armed robberies in the area the year before. The manager helped detectives to examine the cash register and office safe, both of which were closed and undisturbed. Because of the holiday weekend, no one had taken a deposit to the bank in three days, so the safe contained over $10,000. Yet the robbers had taken nothing. Perhaps they had lost control of the scene and inadvertently shot someone, then killed the others to eliminate witnesses. Possibly, violence had not been part of the plan, so they’d fled in case someone had heard the shots.

Starbucks officials announced that security guards would be posted at other nearby stores for an indefinite period of time. The company’s CEO flew into the district to assist, offering a $50,000 reward for information leading to an arrest. This was a first for the successful chain, which had more than 1,200 locations, including 62 stores in the area. In fact, despite the district’s reputation for crime, the incident even shocked city officials.

“To have a triple homicide anywhere in the District of Columbia,” said district Council member Jack Ward, “is an unusual event. To have a triple homicide in Georgetown is extraordinary.”

For everyone’s sake, they hoped to make a swift arrest.

Residents of the neighborhood left wreaths, candles, plants and poetry at the store’s entrance to create a visible memorial. In the absence of police briefings, reporters collected information about the victims, to put faces on them for readers and to give dimension to their lives. All too often, victims are forgotten.

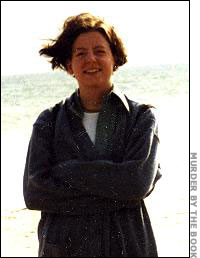

Caity, it turned out, had practiced being bold all her life because “she did not want to live afraid.” Her grandmother had recently bought her the 1994 Saturn left in the lot, so she could get around in the city and feel safer. She habitually jogged alone at night, convinced she’d never be attacked. She had once even traveled as an exchange student to the Soviet Union, and as a White House intern under President Clinton she’d arranged tours.

“She had an enormous heart,” her mother said. “She would probably have compassion for the person who killed her.” Caity, who had a special love for animals, had been just about to turn 26. She’d been employed with Starbucks for two years and had taken special pride in being a store manager.

Emory Evans had worked part-time and was trying to save enough money to attend Howard University, where he’d hoped to major in music. He played the French horn. An only child, he had a reputation for always trying to do the right thing and he enjoyed time with his family back in New Jersey. Aaron Goodrich, a fun-loving high school senior, lived with his father, who had helped him to get the job. As the store’s youngest employee, he had earned the nickname, “Baby.”

A surveillance tape showed that Caity had attempted to escape, but it did not show the shooters. The postmortem examination indicated that she was shot five times, taking four shots to the head, while Evans was shot once in the chest and twice in the head. Goodrich had been shot only once. Investigators wondered if Caity had been the intended target. Such overkill was often a symptom of anger.

Investigators asked about former employees and one lead emerged right away. Caity had recently fired a male employee on suspicion of theft when several hundred dollars turned up missing from the safe. The police obtained his name and address, and went to check him out. He answered all their questions and claimed he had not been involved; when they found no evidence against him, they let him go.

Unfortunately, there would be no quick or easy route to an arrest.

It turned out that there were no usable fingerprints inside the shop, and aside from the shell casings, there was no other physical evidence. A bullet hole found over the safe suggested that a warning shot had been fired, possibly to get an employee to open it, but the safe had not been opened. Only Mahoney had the combination, so detectives surmised that she might have defied the robbers, and been killed as a result.

No one from the area had reported seeing anyone enter the store at closing time, or leaving later. FBI profilers who were consulted said that these killers would have prior offenses on their records. They suggested looking at other area armed robberies, but that effort turned up no clear leads to the Starbucks shooting. The Georgetown Business Association offered a reward of $10,000 for information, and Starbucks paid for the victims’ funerals and for counseling for the families.

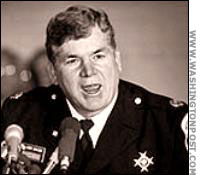

The homicide unit supervisor, Lt. Brian McAllister, insisted that with methodical police work the case would be closed. That meant it was going to take time. In fact, there was little news for several months, despite the concerns of residents and the families’ need for closure. While investigators kept working, as each day passed, it seemed that the case was growing colder and, in a busy area like Washington, D.C., that it might eventually be shelved as low priority. But then something occurred that brought attention back to it.

In the fall of 1997, a woman named Linda Tripp began taping her conversations with Monica Lewinsky, a former white house intern for Bill Clinton. The subject was a long-term affair that Lewinsky claimed to have had with President Bill Clinton. Tripp then played the tapes for members of the staff of Newsweek, but the magazine declined at that time to publish what appeared to be a potentially explosive story.

In the meantime, Lewinsky, 25, had left the internship and was looking for a job in New York (by some accounts, because Clinton wanted to get her away from the Washington media). In December, she was subpoenaed for a sexual harassment lawsuit against Clinton brought by Paula Jones, a former Arkansas state employee. At first, it appeared that the situation would remain moderately low-key, but the initial appearances were wrong.

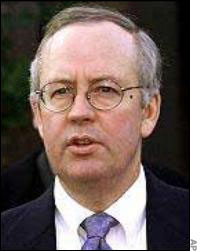

On January 7, 1998, Lewinsky signed an affidavit denying that she’d ever had sexual relations with President Clinton. However, Linda Tripp had Lewinsky’s admission on tape, and she gave it to her own attorney. Tripp then contacted the office of Independent Counsel Ken Starr, who was already investigating the Clintons on other matters. She discussed the tapes with him, along with allegations that Clinton had urged Lewinsky to lie under oath.

The situation grew more complex as Lewinsky obtained legal representation and obtained an immunity agreement, both for her and her parents. She then admitted she’d had an affair with the president. She had in fact visited the White House 37 times since leaving her position there, and the president’s secretary, Betty Currie, admitted to a grand jury that Lewinsky and the President had been alone on several occasions. Others confirmed this.

Now Clinton was on the hot seat, with yet another woman emerging to make a claim about sexual impropriety, and he was required to answer some tough questions. His worst alleged offense, it seemed, was exploiting his authority with Lewinsky, and then instigating a cover-up. Clinton admitted he’d been alone with Lewinsky a few times and had given her some gifts, but denied anything overt: “I did not have sex with that woman.” However, a certain blue dress came to light: Lewinsky had worn it while with him and had saved it. She claimed it bore a semen stain that would corroborate her story. The FBI performed a DNA analysis and confirmed that the stain had originated with Clinton. Seven months after his adamant denial, Clinton finally admitted to inappropriate encounters with her that involved sexual contact. People called for his resignation, but Lewinsky would not say that he’d coached her to lie under oath, so Clinton rode out the storm and remained president.

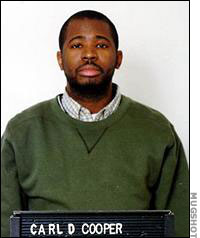

Although nothing concrete ever linked the Lewinsky scandal to Mahoney and the Starbucks shooting, Mahoney’s prior participation in the White House intern program generated renewed interest in the crime, and additional reports about it in the newspapers generated more calls to the police tip line. One of them stood out: Caller 234 implicated a “Carl” who lived on Gallatin Street. He was short, brown-skinned, in his mid-twenties, with a beard. He drove a small car and carried two or three guns. He was “vicious” and had killed prior to the Starbucks incident. He’d even killed one of his partners.

With only this crumb of information, detectives went to work. Via the Department of Motor Vehicles, they had figured out that “Carl” was probably Carl Cooper of Gallatin Street, who drove a Honda Civic and seven arrests on his record. Now they had to work him. Yet the investigation was beleaguered by accusations of incompetence, which only made things worse.

In September 1997, the police were criticized for failing to seize a pair of white athletic shoes from the first suspect, the former Starbucks employee, to compare to evidence from the scene. Apparently a day after they had investigated him, an evidence technician mentioned that he thought he’d seen a dark stain on the shoes. A black-and-white photo affirmed it. The shoes were then seized and analyzed, but the police announced that there had been no evidence on them linked to the slayings. If the suspect had tried removing evidence, such as a bloodstain, that would have been detected by the FBI’s testing.

However, the public maintained its distrust. The Washington homicide units were under scrutiny, Brian Mooar indicated in The Washington Post, because so many of their cases more than 60% remained unsolved. District Police Chief Larry D. Soulsby replaced all the supervisors and began searching outside the city for a new unit commander. By this time, Starbucks had increased its reward to $100,000.

Police continued to seek leads. A drug abuser had told them he knew of a house in Southwest D.C. where the residents had information about the shooting. He agreed to act as an informant, but to do so, he said, he had to purchase drugs from them. The police gave him less than $100 and remained out of sight as he went to the house. This, they believed, would provide legal grounds to search the house and possibly turn up evidence. However, on his way back the informant was brutally beaten and robbed. Found by a passerby, he was taken to a hospital, where he died. His family instigated a lawsuit against the police and the city for knowingly sending him into a high-risk situation without proper planning and protection. They would ultimately win $98 million, the largest jury verdict ever returned against the D.C. government.

Throughout this time, the coffee shop remained closed. People who walked by were reminded of what had occurred there. But finally, Starbucks decided to reopen the shop, announcing a reopening date of February 21, 1998. To honor the victims, they built a floor-to-ceiling Maplewood mural that held three boxes, each engraved with the initials of one of the victims. Their surviving relatives placed mementos into the boxes, and the company announced it would donate all net profits from this store to the Community Foundation for the National Capital Region, an organization dedicated to nonviolence. Starbucks also gave money to Circle of Hope, a group that guided teens toward being productive members of society.

Soon the store was bustling with activity again. By the time a year had passed, as local newspapers marked the tragic anniversary, the case had grown cold. Public officials said little about it, as they knew how difficult it would be to catch the killers at this point, yet two homicide detectives and an FBI agent were still assigned full time. To date, they had interviewed hundreds of people and followed dozens of leads. One officer told reporters that the police were optimistic about solving it, because they had some tips that looked good; they just had to work up more evidence to make an arrest stick. Some people thought that kind of talk was just for public relations, but the police knew what they had. Some cases take longer than others, and this one, while slow, did in fact have a solid suspect.

Jeff Leen wrote the following in The Washington Post: “The essential difference between homicide investigation on TV and homicide investigation in real life is one of degree: The true art of homicide investigation is both subtler and sloppier, much more mundane, and finally, much more sublime a grinding application of routine, the occasional piece of luck, a marathon of wits and will. If genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains, then real-life homicide investigation can have a genius of its own.”

In recent years, increasingly more law enforcement personnel have been assigned to work on cold cases. New technology, a new perspective on a crime, or new leads from someone now willing to talk have already solved many other cold cases, some half a century old. But to be effective, a cold case team must have a viable plan. In other words, they must figure out how best to utilize their resources and then identify something new that can restart a stalled investigation.

Top priority cases have well-developed suspects and evidence that has been preserved and on which a new technology can be used: Biological evidence that can be tested with new techniques or fingerprints that can be entered into databases that now have more prints than before. Cases with too many unknowns or that would involve great expense for little payoff are lowest priority.

Cold case squads or units often have access to outside resources in the FBI’s National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, the U.S. Marshals Service, military investigative services, organized groups of retired personnel, and crime investigation volunteer groups that offer unique services. In the Washington area, especially, they had federal resources.

But often, such cases benefit from a witness or an associate of the offender who now wants to talk. Some may have once felt intimidated by threats that are no longer compelling, or may have left relationships and now feel bitter toward someone they had protected. They may have overheard a killer boast about his crime when his own inhibitions were relaxed, or they may have heard something new since they were last questioned.

Fortunately, a television program about fugitives and unsolved crimes, America’s Most Wanted, has also been a valuable tool in cold case investigations. Thanks to tips from viewers, the program has solved cases more than a decade old and assisted in the arrest of over 500 fugitives. The Starbucks shooting case was developed into an episode for the show, and it aired. Then the program repeated the episode in June 1998, and the second time around, states The Washington Post, it paid off.

A viewer of the show called to say she had dated a man who knew another man named Cooper, and Cooper had claimed to be the Starbucks killer. This was the kind of break the case needed, since Cooper was already on the list of suspects. This woman agreed to wear a wire to get corroboration of what Cooper said. Since the Prince George’s County police in Maryland were already investigating Cooper in the context of another shooting the year before the 1996 attempted murder of a cop named Bruce Howard the Metropolitan Police Department thought the woman’s information was solid. The two jurisdictions pulled together, and with the FBI, built a case.

Among the things they did was to wiretap Cooper’s phone and to mount a surveillance camera on a utility pole outside his home. From this they generated numbers and leads about other people who might have been involved. They also obtained a gun from Cooper’s wife that had been used in another fatal shooting. The case grew complicated, because Cooper had a large network of criminal associates, but his style of killing, it seemed, matched that of the Starbucks incident. Finally, they settled on Cooper as the primary suspect and decided to bring him in.

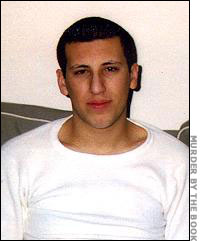

On March 3, 1999, the papers announced that a suspect was being questioned in connection with the crimes: Carl Derek Havord Cooper, age 29. A witness, referred to in an affidavit published by the Washington Post as W-1 (also referred to as “the barber”), told police that Cooper had invited him to participate in a robbery of the Georgetown Starbucks. He said Cooper had already determined that it was a good target, but then never followed up with W-1 to do the job. Apparently, he had gone ahead to complete it on his own.

Cooper had a long criminal record in several jurisdictions, including armed robbery, a string of car thefts, and drug charges. What linked the Starbucks and Prince George’s County incidents was that two handguns of different calibers were used in both, and that, a decade before, when Cooper had been arrested for another offense, he had ammunition on him from two different caliber handguns. The police also had an informant who said that Cooper had admitted to him that he’d committed the 1997 shooting and knew things that only the perpetrator would know.

According to local accounts, Cooper had lived in the northeastern part of DC his entire life and resided there with his mother, wife, and four-year-old son. His deceased father had been a church deacon, and people in the area viewed Cooper as a “nice man.” His first run-in with the law had been over cocaine possession, and then he’d turned to armed robbery. At first he denied the Starbucks shooting, but after he was transferred from one jurisdiction to another, and was caught in several lies, he apparently decided to start talking. What he said at first was misleading, but then he got down to business.

Despite detectives often cautioning him, Cooper waived his right to an attorney and to remain silent, and began implicating two other men. One of them, whom Cooper named as the shooter, had even lived in the same building as Emory Evans and had known him, so this person was picked up. Eight FBI agents questioned him for fifteen hours. He took and passed a polygraph, but was then arrested as a felon in possession of a firearm a charge that was later dismissed. He would later tell reporters he thought Satan was trying to “step” on him frame him just as he was getting his life together. He referred to the Starbucks shootings as “evil.”

But then Cooper finally took credit for the shooting himself. An affidavit, unsealed in a D.C. Superior Court, described the following scenario: For a month, he had planned to rob the Starbucks. He had even approached another man to do it with him. The Sunday following the Fourth of July weekend, he knew, meant the safe would probably contain an abundance of receipts from at least three days. It was a busy shop, so it should be a lucrative take. He couldn’t find his chosen partner that afternoon, so he decided to do it alone: he did not wish to miss his “window of opportunity.”

He went to the shop that morning, after dropping his mother off at her church, to see if business was steady. It was. He could see no surveillance camera, and this confirmed his decision to hit this location. During the evening, around the time he knew the place would close, he drove to rear of the store and parked. He had two handguns with him, a .380 and a .38. snubnose revolver. He liked one for power and the other for accuracy. He then entered the store and announced his intent to rob the shop. There were three employees present, he recalled, two males and a female. He herded them into the backroom.

At his request, the women identified herself as the supervisor and he ordered her to open the safe. She refused, so he fired a warning shot to show her he meant business. He hit the ceiling. She then ran and he pursued her, wrestling with her to get the keys. She made it as far as the sidewalk outside, before he caught her and dragged her back in, but there were no witnesses on the streets. She tried to grab one of his guns, he claimed, so he shot her with the .380. “I kept telling her to give me the keys,” he said, “but she kept fighting me.” Then he used both guns on her. “Everything else was like a dream…I just started shooting.” She had not been targeted with a personal vendetta, it seems, but simply drew fire because she had resisted.

Then Cooper turned his attention to the two frightened young men. He walked into the back room just as one of them began to run, so he shot them both. He shot the black male three times, he remembered, because his first shot directly to the chest failed to kill the young man. That contact wound was consistent with a subnose .38. To end his suffering, Cooper said he shot him twice in the head. He shot the white male only once. Then he left without even trying to get into the cash register or safe. Having just committed a triple homicide, he went directly home, got rid of his guns, and because he “tasted the girl’s blood” in his mouth washed his clothes. He buried the guns inside a plastic bag on the grounds of St. Anne’s Infant Home in Hyattsville, a few blocks from where he lived.

At this point, Cooper was placed under arrest, given a court-appointed attorney, Steven Kiersch, and asked for hair and blood samples for analysis. He claimed he’d have told police about his involvement a year earlier if city detectives had not harassed his family. On March 6, 1999, newspapers announced that Cooper had been arrested as the lone gunman in the Starbucks shootings. One source told reporters, “He’s given up everything.” Yet it would prove to be not quite that simple.

After several hearings, Cooper was charged on August 5, 1999 on a 48-count federal racketeering indictment, which included three counts of first-degree felony murder in the Starbucks shootings. He was also accused in the shooting homicide of a security guard in 1993, the attempted murder of a police officer, and four armed robberies. Often, he worked with others, using masks and stealing cars, so this justified the racketeering charge. U.S. Attorney Wilma A. Lewis said he could seek the death penalty against Cooper, although he had not yet made that decision. In fact, he would ultimately recommend a life sentence.

Kiersch stated his intent to “vigorously contest the indictment,” and Cooper now claimed that he’d been coerced into confessing. He said, “I swear on my father’s grave and my son’s life I didn’t do Starbucks.” Both sides were now in a tug of war over the confession. While it nicely fit the facts, the interrogation had lasted many hours and could be viewed as coercive. The cops who were certain they had closed the case had to sweat it out a while longer.

Cooper plead not guilty to all of the charges. He said that under extreme pressure he had lied about his role in the Starbucks slayings. The police had falsely said they had lifted his fingerprints from the coffee shop, so he’d felt trapped. He’d then told the Prince George’s County detectives what they wanted to hear. Thus, said his attorney, Cooper’s constitutional rights had been violated and his confession should not be admitted into any courtroom proceedings.

Three different detectives testified at a hearing that Cooper had not been coerced; he had voluntarily given his statement. He was offered food, allowed to rest during his fifty-four-hour interrogation, and had been treated fairly. “He was willing to talk to us,” said Detective Troy Hardin, “anxious to talk to us.” They claimed he had waived his right to an attorney, and there had been no question based on his intelligence level as to whether he’d been competent to understand his rights.

The detectives insisted they had advised Cooper repeatedly throughout the four-day, marathon session that he could remain silent or have an attorney present. At all times, he had been focused and comfortable, with no overt signs of anxiety. He had even signed seven statements agreeing to waive his rights and talk, and the descriptions of his crimes were largely in his own handwriting. Three of the statements were about the Starbucks killings. “It was almost like a sense of relief,” said another detective, “as if now this monkey was off his back.”

The police nonetheless were discomfited by this Cooper’s repudiation of his confession. Without the confession, they had little to tie Cooper to the slayings. They had not recovered either weapon in the slayings and had no fingerprints or trace evidence that definitively put him at the scene on the fatal night. While Cooper’s description accurately matched the crime scene and wound patterns, and several of his associates would say he had talked about the incident, that was largely circumstantial.

Public defender Francis D. Carter joined Kiersch to prepare for the trial. They argued that the questioning should have stopped after the initial FBI interrogation, when Cooper had stated, “Killing is not my style” and had denied any involvement in the shootings. A public defender had even insisted at that time that the questioning should stop, and yet later that day Cooper began making statements, presumably at someone’s instigation.

It was now up to a judge to decide.

On February 1, 2000, Senior U.S. District Judge Joyce Hens Green ruled that prosecutors could use Cooper’s statements to the police as evidence in his trial. “The record shows,” she stated, “that Cooper had an easy, comfortable, familiar, confident attitude toward his interrogators. Both on the facts and the law, there is no evidence to show Cooper’s statements were anything but voluntary. Instead they were clearly voluntary, readily and eagerly initiated, and provided free of coercion and duress.” Cooper had no more ground on which to stand. He’d even written on one of his statements, “I’ve wanted to admit this ever since it happened. It had to be known.”

By February 15, prosecutors announced that they would seek the death penalty, under federal rather than D.C. statutes. Attorney General Janet Reno made the controversial decision, which sparked a great deal of criticism. However, there had been some developments.

Investigators had evidence from the wiretaps that Cooper had threatened to kill five people he viewed as potential witnesses against him, as well as two investigators on the case and their families. In addition, he was a suspect in even more armed robberies, and his lengthy record of violent crimes, coupled with his lack of remorse, indicated that he could not be rehabilitated. He was a danger to society, even in prison.

Had it moved forward as a capital case, it would have been the first one for the District in thirty years. The last execution had occurred there in 1957. But before it came to that, Cooper’s attorneys examined the evidence and learned how many of Cooper’s former associates had agreed to testify against him. One of them would describe precisely how Cooper had planned the Starbucks episode. Cooper was persuaded to accept a deal that spared his life and protected his wife and mother from prosecution as accomplices.

On April 25, 2000, a week before his trial was to begin, Cooper came into court to plead guilty to the forty-seven counts against him, including the Starbucks murders. As he admitted to each charge, one after the other, he wept, but he never expressed remorse to the relatives of the victims who packed the courtroom. He received a sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole. Prosecutors also agreed not to pursue charges against his wife or mother, both of whom had assisted him in some manner.

The mother of one of Cooper’s victims said, “You could just detect the demon inside this young man’s body.”

D.C. Superior Court Judge Cheryl M. Long dismissed a multi-million dollar lawsuit, filed in January 2000, against the nation’s firearms makers and distributors. Instigated by the D.C. government and the victims of gun violence, gun control advocates had used the Starbucks incident as leverage. However, in a 103-page opinion, Judge Long found the lawsuit so “fundamentally flawed” that she did not feel justified in moving it to the next step. She rejected arguments that the government was entitled to payment for resources expended on gun violence cases, such as emergency services, police investigations, and medical expenses.

Twenty-five companies named in the suit, the first of its kind in the D.C. district, had filed a motion to have it tossed out of court. Among them were Smith & Wesson, Baretta USA, Colt’s Manufacturing, and Ruger & Co. Judge Long agreed, stating that the suit was full of “legal deficiencies,” not the least of which was the fact that the city’s lawyers had not proven that any act by the companies could be clearly associated with a specific violent incident.

The National Gun Association viewed the decision as a major victory and hoped it would stem the tide of other municipal suits around the country. Thirty states had even passed laws granting the firearms industry immunity from such legal proceedings, in order to avoid numerous frivolous lawsuits from clogging up courtroom resources.

Attorneys for the city noted, however, that in other areas appellate courts had overturned such decisions, effectively reviving them. Thus, D.C. officials would consider whether to appeal Long’s ruling. So many people were maimed or killed each year by guns, many of which were clearly not used for hunting or personal protection, that officials believed the anti-gun movement would eventually reach critical mass and produce needed reform.

“D.C. Judge Rejects Lawsuit against Firearms Makers,” The Washington Post, December 17, 2002.

Fernandez, Maria and Cheryl Thomas, “Detained Man Names Two Others in Starbucks Case,” The Washington Post, March 5, 1999.

“Key Player: Monica S. Lewinsky,” Washingtonpost.com, October 5, 1993.

Leen, Jeff. “A Dance with Death,” The Washington Post Magazine. March 2, 2003.

Miller, Bill. “Starbucks Suspect Faces Host of Charges,” The Washington Post, August 5, 1999.

“Jury Awards $98 Million in Slaying of DC Informant,” Drug Police News, October 21, 1999.

“Statements Challenged in Starbucks Triple Slaying,” The Washington Post, January 13, 2000.

“Cooper Sentenced to Life for Starbucks Killing,” The Washington Post, April 26, 2000.

“Starbucks Case Hit List Alleged,” The Washington Post, February 15, 2000.

“Statements Admissible in Starbucks Slaying,” The Washington Post, February 2, 2000.

“‘He was Willing to Talk’; Police Deny Pressuring Starbucks Triple Slaying,” January 14, 2000.

Mooar, Brian and Linda Wheeler. “D.C. Police Delayed Seizing Possible Starbucks Evidence,” The Washington Post, September 30, 1997.

Slevin, Peter. “Starbucks Manager Resisted Robber, Court is Told,” The Washington Post, March 18, 1999.

“Starbucks Affidavit,” The Washington Post, March 17, 1999.

Thompson, Cheryl. “Starbucks Suspect ‘Just Started Shooting,” The Washington Post, April 27, 1999.

Thompson, Cheryl and John Fountain. “One Year Later, Starbucks Slaying Still Unsolved.,” The Washington Post, July 6, 1998.

Vogel, Steve and Cheryl Thompson. “Three Employees Killed at D.C. Starbucks,” The Washington Post, July 9, 1997.

Wheeler, Linda. “Coffee Shop Emerges from the Shadow of a Crime,” The Washington Post, February 21, 1998.

“Pressure on Police in Starbucks Shootings,” The Washington Post, February 15, 1998.

Wheeler, Linda and M. E. Fernandez,” Police Question Man in Series of Crimes,” The Washington Post, March 3, 1999.

“Lone Starbucks Suspect Charged,” The Washington Post, March 6, 1999.

Wheeler, Linda and Bill Miller, “Undercover Job Costs D.C. Informant his Life,” The Washington Post, December 6, 1997.