George Parkman — Murder and the Expert Witness — Crime Library

Murder trials during the nineteenth century were a significant form of entertainment, especially when they involved surprises. Sometimes they involved surprises even when the trial was over and the verdict in. There was no HBO, MTV, or even radio at the time, so the public avidly read newspapers or assembled outside the courthouse, and the journalists catered to prurient interests. Most of the time, crime was fairly mundane and obvious, but occasionally the characters who came onstage were so unexpected that even daily papers could hardly feed the public’s hunger to know every salacious detail.

In 1849, such a murder trial took place at Harvard Medical College in Boston, and not only were both the offender and victim from the more prestigious classes, but the details of the killing and body disposal were fairly disgusting. It was difficult to even identify the victim with certainty, and that meant relying on experts.

At that time, the legal process was just beginning to acknowledge that criminal investigation could be approached with some degree of scientific technique. Fingerprints had been used in ancient times, there was some use of physical evidence matching, and Eugene Francois Vidocq had established the worlds first detective agency in Paris. Ink dye had been analyzed on documents, poisons found in body tissues, and blood analyzed on surfaces. Only twenty-one years before this trial, the first polarizing light microscope had been invented. In 1839, Scotland Yard caught a murderer through bullet comparisons with a mold, and the first primitive semen analysis for sexual homicide was underway.

Sachs’ Corpse:

Nature, Forensics,

and the Study to

Pinpoint Time of

Death

However, there had not yet been forensic anthropologists or dentists in American courts, or medical personnel to attempt to establish time of death. According to Jessica Synder Sachs, in Corpse, these early days were filled with pseudo-professionals making unfounded claims about their ability to make accurate determinations. The trial of John Webster for the murder of George Parkman marked a turning point for the use of doctors as expert witnesses. “Over the next twenty-five years,” she writes, “the United States moved rapidly to integrate medical experts into its antiquated coroner system, with one state after another authorizing coroners to employ physicians to assist in their investigations of homicides and suicides.”

Thus, this was a precedent-setting case that changed the entire process of death investigation in the U.S. and made a significant impact on the trial system.

Let’s take a look at what happened.

In Murder at Harvard, Helen Thomson describes Boston near the end of 1849it was prosperous and filled with Irish immigrants who carried out most of the manual labor. There was clearly a class consciousness, and among the wealthy “brahmins” was a man named Dr. George Parkman. Nearly 60 years old, he was estimated to be worth some half a million dollars at a time when a dollar meant a lot. He had hobnobbed with the likes of John Adams, second President of the United States, artist John James Audubon, and General Lafayette, hero of the Revolutionary War.

Dr. Parkman owned many tenement buildings on which he collected rents and it was also his habit to lend money, so he kept strict track of his accounts. He would go out walking each day to keep an eye on things and get his earnings. Notoriously thrifty, some say he walked to avoid the expense of keeping a horse. His rushing figure, bent forward from his momentum, was known to everyone in the general vicinity of his home at Number 8 Walnut, and many said they could set a watch by his routines. People wondered how he could carry money around without concern, and that very notion became central in the search for him when he turned up missing one day.

Parkman walking

On Friday, November 23, 1849, a week before Thanksgiving, he went out to see about some of his accountsparticularly one that had given him some trouble over at Harvard Medical College. He was tall and lean, marching in a brisk fashion. His chin protruded to such an extent as he leaned into his stride that hed acquired the nickname Old Chin among those who saw him on a daily basis.

Despite his privileged status, Parkman had been inspired by a lecture given by Dr. Benjamin Rush from Philadelphia to take a keen interest in the miserable state of the mentally ill in asylums. Simon Schama describes his travels for this purpose to Europe in Dead Certainties (Unwarranted Speculations). In 1811, Parkman went to France and met Dr. Philippe Pinel.

Dead Certainties

Pinel was medical doctor to the mentally ill at both the male and female asylums in Paris. He managed them with a crude form of behavioral therapy that relied on rewards and punishments. He also believed in the healing value of nutrition and fresh air, and on treating them as unfortunate people not prisoners.

Parkman became his student, looking into every aspect of benevolent care for such unfortunates and learning about how early events in the lives of many had precipitated their strange manias. The point, he saw, was to bring order into their lives. He made plans to establish such an asylum just outside Boston and he imagined himself its superintendent. Who better to do it than a student of Pinel’s?

When he returned to Boston, Parkman found a receptive committee in the fundraisers for the Massachusetts General Hospital, but they were not as receptive to having him so fully involved. He was enthused, to be sure, and knowledgeable. He had even put down a payment on a mansion suitable for the place and given some indication that he would raise the rest of the money.

Yet in the end, to Parkman’s bitter disappointment, the position at the newly established McLean Asylum had gone to someone else. It was a political move for the hospital, and Parkman ultimately accepted it. He even continued to do what he could to ease the condition of the patients who were housed there. His charity to the mentally ill mitigated his reputation as a stingy miser.

On that November morning in 1849, many different people saw or talked with George Parkman, and had reason afterward to remember it. One woman who owed him money fled from him when he demanded the dollar he had seen in her hand as she tried to pay for food. He expected people to live up to their agreements, and he told them so in a sharp voice. At times, he even got aggressive about it. He liked to help people through a crisis, because he could, but he expected to be paid back promptly. He made his money from rents and from what he loaned. He couldn’t be expected to ignore that. In order to continue to live as he did, he had to make people pay what they owed.

He placed a grocery order for the approaching holidays and had it sent up to his house. To several people he offered Thanksgiving greetings. He left some lettuce with one man to whom he expected to return for shortly. In 33 years of marriage, he had never missed his 2:00 dinner with his wife and he didn’t intend to on that day, either.

But George Parkman never came back for the lettuce and never went home. He was last seen at 1:30 that afternoon in a dark frock coat, dark trousers, a purple satin vest, and a stovepipe hat. He had gone to call on a man at the medical college who he believed had duped him with a bad business deal. Professor John Webster, deeply in debt, had reason to be afraid.

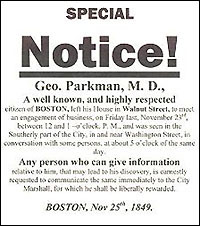

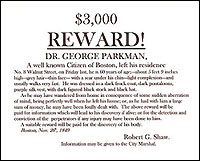

The Parkman family anxiously inquired into the whereabouts of George on Saturday and then contacted the police, who posted a large notice urging people to come forward with information. At the same time, John Webster was telling people his version of a meeting hed had with Parkman on Friday afternoon.

In fact, he admitted that he had been to Parkmans home that morning to arrange it, having finally come up with the money he owed on a debt. Webster, a professor of chemistry and geology, was a short, stocky man with dark hair and glasses. He had higher social aspirations for himself and his family than he could ever afford, but he tried not to let them know that. To deceive his wife and four daughters, he had borrowed money to pay for some of their finery and a nice house, but had been unable to earn that money in the ways that he had planned. That meant continuing to borrow. He would put up his household furniture and his cabinet of valuable mineral specimens as collateral, and he had done as much for the loan of $483.64 from George Parkman. Everything had been agreeable, he said, and he had come up with the money to repay the man. Thats why they were meeting.

At least thats what he told the Parkman family when he came to see them on Sunday afternoon, two days after George was reported missing. Webster had read about the disappearance in the papers and thought that he should come and have his say.

In a strangely businesslike manner, says Thomson, he described the meeting hed had with George at 1:30 on Friday afternoon. Webster had given the money he owed to his benefactor, who had taken it and then walked hurriedly to the door. Parkman had promised over his shoulder that he would go right away to have the payment recorded by the city clerk to clear the debt. Webster had believed it had all been settled. Now he was worried that someone had robbed Parkman and the debt was not clear after all.

John Webster

(Massachusetts

Historical Society)

Then he got to his feet, gave a stiff bow, and left. He failed to inquire how the family was doing or to offer the merest civility. It was an odd manner, and one that the grieving family would have cause to remember later that week. John Webster’s very appointment at Harvard was due to George Parkman’s intervention on his behalf. Had he nothing more to say to them? Was he even worried about the man who had offered him so much help?

In fact, there were those who wondered where John Webster had come up with the money to pay Parkman back. His stipend at the college was only $1200 a year, and he depended for more on the tickets he sold to his lecturesof which he’d had little success. He lived in a house that must have taken all of his money, and had a wife and four daughters as wellone of them married. George Parkman had even commented that Webster had borrowed from several people and had been unable to keep up interest payments on any of those loans.

Something just didn’t add up.

poster

By November 26, a $3,000 reward was settled upon for finding the man alive, and twenty-eight thousand copies of the notice were printed up, posted, and distributed. A little later, $1,000 was offered for his body.

There were those who believed that the mercurial man had suddenly just left the city; there were also rumors that he’d been beaten up for the money he always carried and taken awaysomeone had actually seen him over the weekend, it was said. There were even rumors that a certain man aspired to take Parkman’s place in his home on the Square, comforting the widow and inheriting all the properties. Yet no theory was proven out. Marshal Tukey even had the river and harbor dragged for a body, and sent men to neighboring towns to check, but to no avail. Search parties were formed that went out day and night, yet still there was no news.

The police went into Harvard Medical College twice to look through the place, with special emphasis on the laboratories and dissecting vaults, but they found nothing to indicate that Parkman had even been there. That sent them to Parkman’s buildings, both rented and vacant, and even to abandoned buildings that he did not own.

Reports began to trickle in from people who had seen the man on Friday afternoon, as well as letters to the effect that Parkman had been murdered in various places, such as Brooklyn, New York, or taken on board a ship. These missives were not signed, but were mailed from Boston, and no one knew quite what to believe.

But a Mr. Shaw knew that George Parkman had been in a highly emotional state on the day he had disappeared. Parkman had recently learned that the very same collateral that Webster had offered on the loan owed to him had been used to secure another loan of $600. Parkman had flown into a fury over this fraud and betrayal. He, George, was being cheated, and after all he had done for the man! Clearly he was in a temper when he’d gone to his meeting to have it out.

Littlefield

(Massachusetts

Historical Society)

But someone else was pondering the matter as well: Ephraim Littlefield, the janitor at Harvard Medical College. He and his wife shared the same floor with John Webster’s labshad done so for seven years-and he generally set up the specimens for lectures. He’d seen some peculiar behavior lately and he didn’t understand what it meant.

A few days after Parkman disappeared, Littlefield had encountered Professor Webster in the street, he told the marshal, and Webster had confronted him with the question of whether he had seen George Parkman at the school the week before.

He admitted that he had, at around 1:30 on Friday afternoon.

Webster struck his cane on the ground – an odd gesture – and continued to ask questions: had Littlefield seen Parkman anywhere in the building? Had he seen him after 1:30? Had Parkman been in Webster’s own lecture room?

Littlefield shook his head to these queries, whereupon Webster repeated the details of his meeting with Parkman in the same manner that he’d recited them to Parkman’s family. He was quite precise about the figure he owed and the fact that the debt had been cleared. Then without another word, he walked off.

He had said more in this single encounter than he’d said to Littlefield in their entire association at the college, and the whole exchange was more than a little puzzling to the janitor. In fact, four days prior to Parkman’s visit, Littlefield now remembered, Webster had asked him a number of questions about the dissecting vault, and after the college had been searched, Webster had surprised Littlefield with a turkey for his Thanksgiving dinner. Once again, it was suspiciously out of character.

Then on November 27, Webster had come into his office early and Littlefield had watched under a door, seeing Webster’s feet as far up as his knees, as the professor moved from the furnace to the fuel closet and back. He made eight separate trips, and later in the day, his furnace was burning so hard that the wall on the other side was hot to the touch.

When Webster was gone, Littlefield let himself into the room through a window, all the doors being bolted, and made a strange discovery. The kindling barrels were nearly empty, though they had recently been filled, and there were wet spots in places where there shouldn’t have been. They tasted like acid. All very strange.

The other thing that puzzled Littlefield was how people were beginning to suspect him of some sort of foul play. Parkman had been seen going into the college, said some, but not out. Had the janitor done something?

Almost a week after Parkman’s disappearance, Littlefield was suspicious enough of Webster and tired enough of unwarranted suspicions about himself that he put some extra effort into the search. He knew there was one place in the college associated with John Webster that had not been searched, and his clandestine enterprise over the next several days was to turn the case into one of the most grisly and gruesome Boston had ever seen.

Littlefield borrowed a hatchet, drill, crowbar and mortar chisel, and while his wife stood guard, he went to work. He went down a tunnel into the vault where the wall had felt so hot and began to hack at it right where Webster’s lab privy emptied into a pit. No one had checked that because no one imagined a man might toss a body down into it. Or else, no one wanted to bother looking there.

He went through two layers of brick in just over an hour, and then knocked off to go to a dance. He figured he still had several more layers to hack his way through, and he would work on those the next day.

He worked for quite some time until he managed to punch a hole into the wall, at which point he felt a draft so strong he could not get a lantern to stay lit inside. Maneuvering the lantern, he looked here and there, ignoring the foul fumes and letting his eyes adjust to the dark. Finally he saw something that seemed out of place. He narrowed his eyes and looked more sharply until he just made out on top of a dirt mound the shape of a human pelvis. He also saw a dismembered thigh and the lower part of a leg.

“In the pale lantern light,” writes Thomson, “the pieces of the body looked ghostly white against the black earth.”

His suspicions confirmed, Littlefield began to tremble quite violently. The light went out again and he stumbled in the darkness out of the vault and through the tunnel until he came out into the building. He yelled for his wife and told her what he’d seen. On his hands, as proof, there was blood mixed with the dirt. Then without waiting to put on his coat, he ran to the home of another professor, Dr. Bigelow, who then found Marshal Tukey.

Not everyone was eager to believe that these remains belonged to the missing George Parkman. The vault where they tossed the remains from human dissections was in that lab, so it could be that there was nothing amiss at all.

By the time Tukey arrived at the college, the word had spread, and a whole party of men was waiting for the official report: were these the remains of George Parkman?

Tukey first had Littlefield go through the dissection room and inventory the specimens to make sure that none was missing. Then several men went into the tunnel and moved toward the vault. It was a nasty business and they finally decided upon the man with the longest arms to go into the privy and hand out the remains, one by one.

He went in and handed out the pelvis, the right thigh, and the lower left leg, and these were placed on a board to await the arrival of the coroner, Jabez Pratt.

When this was done, Marshal Tukey went out to arrest John Webster on the charge of murder.

Webster was quick to throw the blame on Littlefield. He asked if someone had found Parkman, and when no one responded, he asked again if they had found the whole body. Then when it became clear that they had searched his privy, he mentioned that Littlefield was the only person besides himself with access to it.

Then he lapsed into silence and would say nothing else. He just sat there at the jail, trembling and sweating. He put something into his mouth, which he later admitted was poison, but it only made him ill.

As the investigators wondered about the rest of the body, the obvious answer seemed to be that it had been burned. In fact, Littlefield had found a bone fragment in a furnace in the laboratory to which Webster had access and showed it to the marshal.

That discussion led to a full search of the toilet area, with Webster brought in from the jail to observe, and while the officers and coroner were thus engaged, Littlefield showed them a piece of the furnace that he’d broken off, on which a piece of bone was fused. They insisted he put it back where he found it.

Webster watched in silence as they laid out the parts they had already found, and then he was carted back to jail.

The following day, a coroner’s jury was assembled to make a judgment about the disposition of the case. Before they were let in, the coroner and marshal’s men examined a sink that appeared to be recently gouged in several places, the strange acid stains on the floor and steps, and the contents of the furnace (from which they extracted a button, some coins, and more bone fragments, including a jaw bone with teeth). Then they dumped out a chest from which came a foul odor, and there was an armless, headless, hairy torso. It was clear that an unsuccessful attempt had been made to burn it. Just as they determined that the head had been sawn off, they found a saw nearby. Then they found a thigh stuffed inside the torso, and the heart and other organs missing.

medical building

(Massachusetts Historical Society)

Mrs. Parkman identified the body as her husband’s from markings near the penis and on the lower back. His brother-in-law said that he’d seen the extreme hairiness of Parkman’s body and confirmed that it was him.

In subsequent searches, they came up with bloody clothing belonging to Webster, and then found the right kidney. Testing on the stains showed them to be copper nitratea substance effective for removing blood, and Dr. Jeffries Wyman arrived to identify the bone fragments.

Since they were already at a medical college with good facilities for the examination of a body, they laid out the parts, tested them, and wrote up thorough descriptions. They conjectured that a hole found underneath the left breast might have been the stab that had killed the victim, although it did not resemble a wound and there was no blood. By the end of the day, they had estimated the man’s height to have been five feet ten inchesan exact match to George Parkman.

As much as the evidence appeared to point directly to Dr. John Webster, few could believe he was capable of such a terrible crime. And they all knew that there was another person who had access to all the same areasEphraim Littlefield. In fact, he had a reputation for digging up fresh corpses to supply to anatomists, who paid him $25 each, so he certainly was used to bodies. He also had no compunction, if the rumors were true, about breaking the law. He claimed to have discovered the body parts, but perhaps he had planted them there to frame the good professor.

Which of these menif eithercould be proven beyond a reasonable doubt to be a killer? Could they even prove that the body parts belonged to George Parkman?

On December 6, a funeral was held for Parkman, and thousands of spectators lined the streets to watch the procession. Some five thousand had even taken a tour of the medical college to see where the grisly deed had occurred. Just as interesting to everyone was the question of who would defend John Webster, and the discussions over all these details were heard everywhere around town.

The famous orator, Daniel Webster, was approached for the job. Featured in a tale, The Devil and Daniel Webster as the kind of clever man who could take on the devil and even beat him before a jury composed of the notorious dead, he could clearly put up a fight for the accused. However, he was crushed under his own workload. While he was interested in what would happen, he declined to be the star attraction.

Despite the difficulty in finding a willing lawyer, John Webster began to write out his own defense in detailwhat he knew to have happened and how best to approach the jury to prove his innocence. He expected that anyone who defended him would abide by it.

The prosecution had some problems as well. The remains were in such a poor state that it was difficult to determine the identity of the victim. In fact, the inquest jury who was to decide whether a trial should take place wondered how anyone could know for sure that these were not remains from dissection, a normal course of endeavor at a medical school. They also pointed out that the two thighs found were entirely different sizes, and the coroner had to patiently explain to them that one had been exposed to fire and had been left inside a torso, whereas the other one had been waterlogged down in the privy. They could still be from the same person. Yet in the end, all they had were pieces, not a whole body, and to that point, no one had ever been identified by such small bone fragments. It would be a difficult case.

The inquest jury’s written decision took up 84 pages, and they decided that the body parts were indeed those of George Parkman, that he had been killed and dismembered at the medical college, and that John Webster was accountable for it. Later, using these findings, the grand jury returned a True Bill and indicted him. According to the actual report, they believed that Webster had assaulted Parkman with a knife, and also had beaten and struck him until he was dead. The exact cause of death was not spelled out.

During this time, the press was looking into every episode of poor behavior on Webster’s part and reporting them to the populace. The initial shock and disbelief about an esteemed professor was turning into anger at this unstable, undignified, nasty man. He even abused dogs!

Nevertheless, Webster fully believed that he would be acquitted and he presented himself in good spirits to his visitors in prison. His family fully supported him.

The court gave him a list of attorneys, and he chose Judge Pliney Merrick and Mr. Edward Sohier. Both were Harvard graduates. However, rather than discuss trial strategy with them, Webster handed them his prepared papers. Basically it was the same story he had told to everyone else: he’d asked Parkman to come to the college to collect his money, had paid it in full, and had received assurance that it would be recorded as such. He had no knowledge about the body parts found in his privy.

The trial began late on March 19, 1850. Judge Lemuel Shaw, 68, presided. It was to last 12 days, and according to Thomson, some 60,000 people saw at least part of the proceedings, which made for a somewhat noisy and chaotic atmosphere, not the least of which were the shouts for silence.

It was a large courtroom with a prisoner’s dock to the left, surrounded by an iron railing. The judge sat across from the dock. To the right of the bench was the jury box.

The defendant was neatly dressed for his first day in court, carrying gloves. Within an hour, to everyone’s surprise, 61 men were questioned and from them 12 were empanelled in the jury box who said that they had not formed an opinion about Webster’s guilt or innocence. It seemed impossible to have a jury seated so quickly.

Attorney General John Clifford talked for three hours about the facts of the case and a review of the evidence that would be presented. He used vivid imagery to convey the brutality of the crime, how Parkman had been killed and his skull fractured. How his parts had been burned or dumped into a toilet. Then his junior associate called witnesses who had participated in the investigation, although they admitted that they would not have recognized the remains as George Parkman’s. The man had been too damaged.

The next day, the jury visited the Medical College to see the scene of the crime. They even went down to the privy pit to lean in and see where the remains had been found. Then they were shown a model of the college, made by a local dollhouse carpenter, which Marshal Tukey used as a tool for explaining the stages of the investigation.

When the coroner took the stand, he described Webster’s behavior upon being arrested for the murder as “mad,” which puzzled people. Webster’s lawyer made no move to object to this portraiture. No one could understand why.

More enticing to the press was the testimony of a physician who talked about the requirements for burning a corpse – he had once done so – and how bad it would smell. Then someone from the college discussed the differences between the typical specimens they used for dissection and those found after Parkman’s disappearance. They were not the same.

Dr. Wyman, in charge of the bones, had drawn a life-size skeleton showing which parts of the body had been recovered. Another doctor described it all to the jury.

The defense attorneys asked enough questions to put into doubt the fact that anyone could actually identify these remains as those of George Parkman. They also sought to establish that the so-called “wound” between the ribs had been inflicted post-mortem in the routine process of dissection. They wondered, if it had killed a man, where all the blood was. No one had yet explained that.

By the third day, it was clear that the prosecution was relying heavily on medical testimony. First, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, dean of the Harvard Medical College, took the stand and said that he believed that the dismembering was done by someone with knowledge about human anatomy and dissection. He also said that a wound between the ribs would not necessarily produce a lot of blood, and that the remains were “not dissimilar” to Parkman’s build.

Dr. Wyman again described the bones, saying that in the furnace he had found bones from the head, neck, face, and feet, and he used actual bone fragments to demonstrate how they fit together. Then Dr. Nathan Keep, Parkman’s dentist, discussed the fact that the jawbone found in the furnace with the false teeth still fitted into it was in fact that of George Parkman. Dr. Keep recognized his own handiwork. He had made an impression of the jaw, which he still had, and it fit exactly the jawbone found in the furnace. The jury got to see and handle this plaster cast.

In the midst of his testimony, the fire bells rang outside. It turned out to be in the building where the attorney general had his belongings, so he asked to be allowed to go fetch them. Webster chatted happily with friends during this recess.

Then Dr. Keep resumed. When he demonstrated how the loose teeth found in the furnace fit his plates, he burst into tears. Then he pulled himself together as the court waited and proved by an inscription that the mold had been made specifically for Dr. Parkman.

This testimony seemed fairly definitive, but that was not to be the end of the dental evidence. The defense had its own expert.

But first Ephraim Littlefield would tell his story.

Littlefield had known both men for yearsDr. Parkman as long as two decades. He recalled the victim demanding repayment of a debt on November 19, four days before he disappeared. That same day, Webster had asked him about the construction of the dissecting room vault, specifically as to whether one could get a light down inside. Littlefield answered in the negative, due to the foul air. Lights went out immediately.

Then there was another factor: once Parkman had disappeared, it had proven difficult to get into Dr. Webster’s rooms, he said. After that, Webster had given him the turkey for his dinner, and it was the following day when he’d felt the intense heat in the walls that had made him suspicious enough to go into the tunnel and dig into the privy.

The defense attorneys suggested that he was in it for the reward money, but he denied it. “I never have made or intend to make any claim for either of the rewards that have been offered,” he insisted. (Eventually, however, he did accept $3000 from Parkman’s family.)

Littlefield made a strong impression on the jury. He was confident and seemed honest, and there was nothing the defense could do to break down his story. What they did not do, although Webster had suggested it in his prepared document, was to accuse Littlefield himself of doing the deed.

The court recessed for Sunday, and on Monday, everyone returned for the examination of Webster’s financial difficulties. It was clear that his amount of debt and his living expenses hindered his ability to repay the loan to Parkman. It wasn’t at all clear where he could have gotten the money. That meant to the jury that Webster had lied.

After all this, it was back to the body and more grisly details. A police officer testified about finding the torso in the tea chest, and the chest was then displayed. It was clearly stained with blood. Then he discussed how it was possible to fit the other parts down the privy hole, but not the torso.

Some witnesses talked about Webster’s uncharacteristic behavior after Parkman disappeared, and finally, three letters were brought into evidence that had been written to deflect the investigation away from the medical college, and all were unsigned. A man familiar with Webster’s handwriting testified that he believed that Webster had written all three letters. Even worse, Webster’s handwriting was recognized on the face of one of Parkman’s loan notices, saying “Paid.”

Aside from a witness who put Parkman on the steps of the medical college in the early afternoon on Friday, the prosecution rested its case.

The defense attorneys, who believed their client’s position was precarious at best, took less time to present their own experts in refutationonly two days altogether.

Sohier talked for a long time about conceptual issues and then said that it was a travesty that Webster could not speak out in his own defense. He talked about the difference between murder and manslaughter, which was to leave the impression that he did indeed believe that a homicide had occurred. It wasn’t a good strategy, Schama points out, but the idea was only to try to break one link in the chain that the prosecution had made. Just one would do the trick. He insisted that the government had not shown beyond all reasonable doubt that Webster had killed Parkman, nor even the manner in which Parkman had died.

Sohier produced 23 character witnesses for Webster’s amiable nature and seven witnesses who said they had seen Parkman since the time he was said to have disappeared. He hoped that would have a cumulative impact on the jury.

Then he brought out the medical experts who conceded that it was difficult to definitively identify these remains, or to say how the person had met his end. Some of them had testified for the prosecution and now were there for the defense. Dr. Willard Morton, a famous dentist around town, said there was nothing in the jawbone found in the furnace to mark individual identification. Lots of people had protruding jaws. He produced a few false teeth of his own making, Sachs indicates in Corpse, which fit nicely into the mold made by Dr. Keep. It was a strong moment for the defense.

The prosecution’s case, Sohier pointed out, was “indirect, presumptive, and circumstantial.” With that, they rested, and the rebuttal began.

Three dentists testified that an artist knows his own work, and a physician estimated that the condition of the remains was consistent with the time period in which Parkman had been gone.

To end it, the defense spoke for six hours on key allegations that the prosecution had to prove 1) that the remains were those of Parkman, 2) that Parkman had been forcibly killed, 3) that Webster had done it, and 4) that he had done it with malice and forethought. Since the defense attorneys had shown that Parkman had left the building on Friday afternoon, the entire case fell apart. Even if the remains were proven to be Parkman’s it was possible that some unknown person had killed him and disposed of them in the college. (This last addition was a serious blunder because it confused the issue and seemed unbelievable.)

The prosecution took more than an entire day in court to present its own closing argument. In a logical manner, Clifford reiterated the events as he saw them and reminded the jury of the strong medical testimony. He thought there could be no reasonable doubt that Parkman was dead and that he’d been located in pieces inside Webster’s lab. He then reminded jurors of Webster’s debt and his activities prior to Parkman’s disappearance.

Finally came the moment that many people had been waiting for. Judge Shaw invited Webster to speak on his own behalf.

Although his attorneys had strongly advised against it, Webster rose to do so. He felt that they had not used the evidence he had detailed for them, so he wanted to present it now. At the end of his recital, which did him neither good nor ill, he turned to the audience and called on the writer of the anonymous letters to come forward and make himself known.

No one did.

Now it was the judge’s turn, and he faced the difficulty of having no dead body. He went on to interpret the rules of evidence regarding the corpus delicti in a way that raised many eyebrows. All they needed was a reasonable certainty, he said. That was a first (but would not be the last such time in an American courtroom). It was an interpretation that swung the vote against John Webster.

Shaw then charged the jury with making a decision.

The jury members began their deliberations with prayer and then went over the evidence, piece by piece. Votes were taken, and on the question of whether the remains were Parkman’s, the response was unanimous. They all also affirmed that Parkman had been killed by John Webster. They discussed whether it had been a willful act, and finally decided that indeed it had been.

On that very same evening that they went out to deliberate on the matter, the jury said they had returned a verdict. The prisoner was led to the dock and the courtroom filled up. The jury came in and the judge asked them about their finding.

“Guilty!” the foreman said.

John Webster was stunned. He sat down and put his head in his hands. Emotion swept through the courtroom, even among those who believed him guilty.

At a later date, he was sentenced to be hanged.

The lawyers submitted a writ of error against the judge and the manner in which he had charged the jury, which was denied. Webster asked for a full pardon, also denied.

Then he made a surprising move: he admitted to the homicide. Ironically, it was a last-ditch effort to save his own life. He said that he had indeed killed Parkman, but had done so in self-defense when Parkman had become belligerent over the debt. It was an act of passion and provocation, not willful, malicious murder. He said that Parkman had been angered over the fact that the mineral cabinet, which had been mortgaged to him, was then put up for collateral on another loan, so he had come in demanding to be paid. It had scared Webster, who had picked up a stick and beat him off. Webster also pointed out that if he had premeditated the murder, he’d have behaved quite differently in several ways and certainly would not have killed the man at the college. And finally, he admitted to authoring one of the anonymous letters. But only one.

It was a clever gesture and it did earn the sympathies of people willing to sign petitions to commute the death sentence, but it didn’t work. That he could conduct his life in so regular a manner for a week, and even enjoy himself and his family while knowing he had committed this deed, looked very bad. His sentence remained the same.

On August 30, 1850, John Webster was marched to the gallows and hanged. He died within four minutes and was later interred at Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, disguised to prevent body snatchers from getting at it.

After Webster died, there was a great deal of public protest and hindsight evaluations of the trial strategy. The evidence was highly circumstantial, many insisted, and the reasons for Webster’s sudden uncharacteristic aggression lacked credibility. The debate endured, and the case continued to inspire interest for some time as far away as Europe. During that time, crime historians called it “America’s Most Celebrated Case,” and even Charles Dickens came to see for himself the room where George Parkman was murdered.

Yet for the legal system, the murder trial was a turning point. Ever after, the medical expert became a central figure in the evaluation of deaths and death investigations, and the politicized coroner system inherited from England began to give way to a system using medical examiners. More states than not now employ medical examiners as coroners or in place of coroners, and someday the entire country may yield to a uniform practice. “Legal medicine” became a subspecialty of training in pathology, and even more precision about postmortem details was introduced into criminal testimonies. Despite the complaints in 1850, the Webster trial made important forensic progress.

“Murder at Harvard,” www.sociallaw.com

Nickell, Joe and John Fischer. Crime Science: Methods of Forensic Detection. University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

“The Parkman Murder,” www.spypondproductions.com

“Report of the Trial of Professor John Webster,” found at www.law.du.edu.

Sachs, Jessica Snyder. Corpse: Nature, Forensics, and the Study to Pinpoint Time of Death. Cambridge, MA: Persues Books, 2001.

Schama, Simon. Dead Certainties (Unwarranted Speculations). New York: Vintage, 1991.

Thomson, Helen. Murder at Harvard. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1971.

“Where is the Body, or the Case of the Missing Corpus Delicti,” www.lawbuzz.com.