Paul Kelly, Killer Actor — A Love Intrigue — Crime Library

Dorothy Mackaye had some explaining to do.

Her husband had turned up dead after a fistfight with a man who, in the estimation of anyone with common sense, appeared to be her lover. Goodness no, Mackaye insisted. Paul Kelly was merely a dear friend.

But hadn’t they “partied around,” as she put it? Hadn’t they spent nights together at his Hollywood Hills home and exchanged gushing love letters?

“Well, you see,” Mackaye explained, “Hollywood is different. We accept violations of convention because it is all right for us — that is, professional people are less conventional, more sophisticated.”

She described her relationship with Kelly as “clean, beautiful and platonic.”

But the American public, unsophisticated or not, wasn’t buying it.

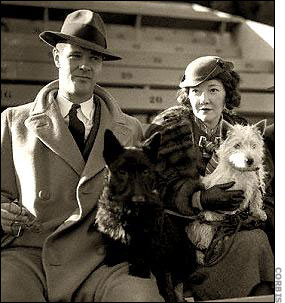

It smelled like a love triangle, and the sexy saga of Kelly, Mackaye and her husband, Ray Raymond, would become the Hollywood scandal of its day, the Roaring Twenties. It was a prototype Hollywood “love intrigue,” lubricated with gin fizzes and featuring three prominent performers.

Dot Mackaye, a comedic actress in the style of Lucille Ball, was “the toast of the theatrical world,” as one newspaper put it. Ray Raymond was a tireless song-and-dance man who traversed the country plying his trade — from Broadway to motion pictures to vaudeville houses.

And the man who came between them, Paul Kelly, was a child actor from Brooklyn who became one of the country’s busiest supporting actors, on stage and screen.

The affair offered Americans — gaga with star gazing even then — a glimpse into the wanton Hollywood lifestyle.

Raymond apparently was not as hip as his wife and her bosom buddy. He warned Kelly to stop bird-dogging his wife, and when the warning failed, he invited him over for a punch in the nose.

It was quite an affair. But it wasn’t much of a fight.

On April 15, 1927, Ray Raymond returned home after weeks on the road with a touring production of “Castles in the Air,” an English farce.

Mackaye was there to greet him, but just barely. She soon slipped out for what she claimed would be a long afternoon of shopping for Easter Eggs. Instead, she bunny-hopped over to Paul Kelly’s place and spent the afternoon in what one writer described as a “gin wingding” with her presumed lover and another couple. The jazzy drink of the moment was the gin fizz, and the two couples downed at least six rounds, police were later told.

As he drank, Kelly worked up a gullet full of bluster over reports from mutual friends that Raymond had been calling him a marriage-breaker.

Truth apparently was no excuse.

At 6:30 p.m., Kelly phoned Raymond.

“When he came to the phone, I told him that I had heard that he was talking about me and that I wanted him to cut it out,” Kelly later told police. “Raymond said, ‘You’re damn right I have, and I wish you were here right now so that I could give you what you deserve.'”

Kelly replied, “I’ll be right over.”

He rushed to the house — located, conveniently enough, just a few blocks away from his flat. Kelly stood at the door and loudly demanded that Raymond step outside. The maid, Ethel Lee, convinced him to step inside instead, and the two men sat together on the couch.

“I asked what he means by talking about me, and he began to accuse me of caring for his wife,” Kelly said. “One word led to another and I slapped him several times. I then got up and went into the kitchen to get a cigarette from the maid. Raymond followed me, and as he neared the kitchen door he screamed, ‘I’ll get you, you son of a bitch.’ I was blind with rage and I hit him several times.”

Paul Kelly was a broad-shouldered six-footer, with the build of a light heavyweight boxer. Ray Raymond was built like Fred Astaire — fit but wispy, and not match for Kelly. According to the maid, Raymond insisted that he didn’t want to fight, but Kelly taunted him for being “yellow.” As the maid begged Kelly to stop, he thrashed Raymond, knocking him down three times. The fight ended when Kelly knocked Raymond out cold with a vicious blow to his left eye.

The Los Angeles Times called it a “one-sided fistic encounter.”

Kelly went home and reported the results of the fight to Dot Mackaye, who was still drinking at his place. She said she bawled him out.

“He (Kelly) said he was terribly, terribly sorry,” Mackaye said. “I told him… that he shouldn’t be so hot-tempered.”

She went home and found her husband wearing dark glasses to hide his black eyes. The maid said the couple joked about the fight. Raymond insisted he was feeling fine, despite an egg-sized lump at his left eye. Mackaye tucked him into bed.

The next morning, Ethel Lee found Raymond in a stupor on the bedroom floor. Mackaye called Dr. Walter Sullivan, a personal friend, who arranged to have Raymond quietly admitted to Queen of Angels Hospital.

Raymond lapsed into a coma and never came out. He died three and a half days after the fight, at 5:20 a.m. on April 19. An actor friend was sitting vigilantly at his bedside. His wife wasn’t. She was at Kelly’s place, as usual.

Dr. Sullivan signed a death certificate claiming that Raymond had died of natural causes, at the advanced age of 39. He had the body spirited away to the Leroy Bagley Mortuary on Hollywood Boulevard. Except for the press, Raymond might have been embalmed and planted in the ground before any authority figure even knew he was dead.

But busybodies at the hospital phoned the newspapers with a tip that the celebrity actor had died after a beating, and scribes called the coroner, who grabbed the body back in from the mortuary for an autopsy. The pathologist reckoned that Raymond had died of brain hemorrhaging from the beating. The district attorney had a celebrity homicide and attempted cover-up on his hands.

Police heard over the transom that Mackaye and Kelly were an item, and Kelly was invited in for a chat with detectives just hours after Raymond’s death was discovered.

His hands shook so that he could barely hold his cigarette.

He may have been nervous, but he wasn’t coy. He admitted that he was in love with Mackaye and that he hoped to marry her one day. He insisted the fight with Raymond was a fair “duel.”

Cops got another perspective from Ethel Lee, the Brooklyn-born maid who was the only eyewitness to the fight other than the pugilists themselves. Lee said Raymond had absorbed blow after merciless blow. The bigger, stronger Kelly put Raymond in a headlock and bashed him in the face six or seven times, the maid said. Raymond was knocked to the floor several times as Kelly needled him to fight like a man. He finally made a few flailing swings at Kelly before the final fist to his left eye ended the thrashing.

Police were anxious to speak with Mackaye, but the poor widow had collapsed at Raymond’s funeral, and she was unavailable to detectives for days after — sedated with a sleeping powder.

More than a week later, she was finally interviewed at her home by a posse of lawmen — two lieutenants, three investigators and an assistant district attorney. She lay in bed with reddened eyes and responded dolefully to questions posed by Detective Lieutenant Joseph Condaffer.

Wasn’t it true that Kelly was in love with her and that they hoped to be married?

“He was a serious-minded boy and talked about marriage quite often but it was so remote that I didn’t even think about it,” Mackaye said.

Wasn’t it true that Raymond had discovered their affair?

“I told my husband I wouldn’t stay away from him,” Mackaye said. “He (Raymond) was so silly, ridiculous and absurd about our friendship — and insanely jealous. He wasn’t in his right mind…He just didn’t understand.”

Cops went away shaking their heads over Mackaye’s warped reality.

On April 21, a grand jury charged Kelly with murder. Four days later, Dot Mackaye and Dr. Sullivan were indicted for conspiring to cover up the true cause of Raymond’s death.

No doubt Mackaye didn’t see that coming.

Raymond, Mackaye and Kelly were three of a kind.

Raymond was born in San Francisco in 1888 with greasepaint in his blood. His family moved East when he was boy. He spent his formative years in Forest Hills, Queens.

Born Ray Cedarbloom, Raymond grew up to become an all-purpose comedic song-and-dance man, in style of Bob Hope. He was built like a hoofer, at five-foot, seven-inch and a wiry 135 pounds. He was working steadily in variety shows and vaudeville by age 18. He married another performer, Florence Bain, when he was 21.

Raymond and Mackaye met in 1921 during a run of the comedy “Blue Eyes” at the Shubert Theater. At age 33, he had a featured role. Mackaye, 21, was an understudy.

She was a vivacious redhead who could not be considered a conventional beauty, with a ski-slope nose and wide-set eyes. But she was a fetching young woman — quick with a smile and a wisecrack. She was born in Scotland in 1899, but her parents immigrated to the U.S. when she was a toddler. She spent her childhood in Denver and was drawn to the New York theater boards while still a teenager.

She made her Broadway debut in 1917 in a 15-performance flop, “The Very Idea.” During that brief run, she became acquainted with Paul Kelly, a fellow teen actor who was working at a theater down the street.

Four years later, during the three-month engagement of “Blue Eyes,” Ray Raymond winked at Mackaye, and she winked back. Raymond dumped his wife and replaced her with Mackaye. She claimed they eloped that Aug. 1 and were married by a justice of the peace in Gretna Green, Maryland. Their daughter, Mimi, was born 14 months later.

But the first Mrs. Raymond claimed that her husband had not bothered with a divorce. Bigamy may have been a moot point since no one could find a Gretna Green in Maryland, let alone a marriage license. Mackaye explained that the document was burned in a fire at her home in New York in 1923.

Whether married or not, Raymond and Mackaye became a well-known stage couple in New York during the Roaring Twenties. He worked vaudeville and an occasional Broadway show, while Mackaye became a comedic darling.

She won a series of ever-larger roles in musical comedies — including “Seeing Things,” “Getting Gertie’s Garter” and Jerome Kern’s “Head Over Heels” — before landing the juicy role of “Lady Jane” in Arthur Hammerstein’s “Rose-Marie,” which enjoyed an 18-month run at the Imperial Theater.

In the spring of 1926, the couple and their daughter Mimi joined the parade of New York stage actors who headed west to cash in on the Talkies.

No one knows whether it was coincidence or conniving, but Paul Kelly made the same move just a few weeks later.

Kelly, born Aug. 9, 1899, got into the acting racket as a result of geography. His Irish-immigrant parents, Michael and Nellie, ran a saloon, Kelly’s Kafe, in the shadow of Vitagraph Studios, on East 14th Street in Midwood, Brooklyn. Studio hands often drank their lunch at Kelly’s, and some would grumble about the incompetence of child actors hired through studio patronage.

Nellie nettled casting assistants into taking a look at her son Paulie, a cute little redhead with a face so Celtic that it that looked like a map of County Cork. In no time he went from a $5-a-day extra to a featured juvenile in roles in silent short comedies.

He appeared in scores of shorts from 1906 to 1916 — titles like Jimmie’s Job, Billy’s Pipe Dream and Cutie Tries Reporting. He had a recurring role as son Willie in Vitagraph’s Jarr Family comedies, shot during World War I.

Kelly also worked on stage. He made his debut in 1907, at age 8, as a drummer boy in David Belascov’s production of “The Grand Army Man.” His first major stage role came at age 17 in a production of Booth Tarkington’s “Seventeen,” and he appeared opposite Helen Hayes in a production of “Penrod,” another Tarkington novel.

Kelly matured into a tall, athletic, handsome young man with a thick auburn mop.

In 1922, he won top billing in “Up the Ladder” by Owen Davis, which ran for a respectable 117 performances. He followed that with featured roles in “Whispering Wire,” which had 352 performances, and “Chains,” with 125 showings at the Playhouse Theater. He seemed poised for leading-man stardom.

But his luck ran out. He followed “Chains” with a streak of five flops, none of which ran for more than a few weeks.

In March 1926, when “Find Daddy” closed after just 16 performances, Kelly headed to Hollywood to find a place in the new home of American cinema.

Hollywood was not exactly awaiting his arrival.

He won just a single acting job in his first six months in Los Angeles — a supporting role in The New Klondike, a comedy about the Florida land rush.

Dorothy Mackaye, meanwhile, was living the lonely life of a road-company widow. Her husband was busy on the West Coast theatrical circuit, leaving Dorothy at home with Mimi for weeks at a time. It was during one of Raymond’s trips that Dorothy Mackaye became reacquainted with her old friend Paul Kelly from their teen days on Broadway.

“I met Kelly when he was a kid actor in New York, before I knew my husband,” she later said. “He was down and out when I met him again… and I took pity on him.”

The Raymonds lived in a lovely home at 2261 Cheremoya Ave., in the Hollywood Hills. By curious coincidence, shortly after rekindling his decade-ago friendship with Dot Mackaye, Kelly rented a house at 2420 N. Gower St., just three blocks from her home.

Ray Raymond returned from the road at Christmastime in 1925 and was surprised to find Kelly sitting on his sofa. The two men were acquaintances from New York, where they had been members of the same thespian social club.

But Raymond suspected funny business, and he ordered Kelly out of his house — permanently. As Dorothy stood listening nervously, the two men had a peculiar exchange right out of a Broadway love farce.

“You think I’m in love with your wife, don’t you?” Kelly demanded.

Raymond replied testily, “You’re right. I do.”

Kelly responded, “And you’re right. I do.”

Before and after the fatal fight, Mackaye had simply decided to deny the affair, no matter what the evidence.

“My husband was always accusing me about Paul Kelly, but his accusations were untrue,” she told police. “Paul was my friend. Our friendship was so clean, lovely and beautiful that I didn’t want to give him up.”

Yet Kelly’s house boy, a young Japanese immigrant known as ‘Jungle,’ revealed that he had served breakfast to Mrs. Raymond after a number of their all-night pajama parties in Kelly’s bachelor pad. Her insistence that their friendship was innocent became even more absurd when a stack of Kelly’s love letters were found tucked in her marital mattress. The letters showed Paul Kelly was sublimely in love — a run-giggling-through-the-daisies sort of rapture.

“I am so terribly in love with you — so terribly,” Kelly wrote. “I am miserable without you. I love you-love you-love you-love you.”

It was torture for them to be apart.

Mackaye had won featured roles in the Los Angeles staging of two comedies, “The Dove” and “The Son-Daughter.” The work took her to San Francisco briefly, and she and Kelly daily exchanged telegrams filled with yearning prose. She signed her cables with the curious “E. Mrs. K.” She later sheepishly explained that it stood for “Elegant Mrs. Kelly.”

Although she steadfastly insisted they were mere friends, it became increasingly obvious that she loved him-loved him-loved him-loved him back.

Kelly’s trial, held just a month after Raymond’s death, was a national spectacle, with coast-to-coast newspaper coverage. The Los Angeles Times said it was the most heavily-attended trial in the history of California.

W.I. Gilbert, the chief defense attorney, sneered that people had packed the courtroom to “hear something salacious.”

Addressing the crowd, he added, “Clean-minded people stay at home.”

Throughout the trial, Gilbert referred to his client Kelly as “that young man” and “that boy,” even though he was 27 years old.

“There are two sides to every story,” Gilbert told the jury. “Kelly was not entirely responsible for what happened. Raymond was partially to blame also. He met up with a lady he had known back in New York who happened to be married. But he had nothing to do with the breaking of their home.”

Wags in the gallery chuckled at that naive assessment, and Judge Charles Burnell threatened to clear the courtroom.

Gilbert had an uphill battle proving Kelly innocent.

Maid Ethel Lee testified that Mackaye rarely slept at home while Raymond was on the road. Jungle, Kelly’s houseboy, confirmed that her primary place of repose was under the covers with his boss.

The love letters and telegrams admitted as evidence didn’t help Kelly’s cause.

The trial reached its sexy crescendos when Kelly and Mackaye took the witness stand.

Kelly was subdued and appeared nervous. In carefully measured testimony, he revisited the details of his statement to police. Yes, he was in love with Mackaye. He resented Raymond’s insinuations about the legitimacy of his love so he went to the house to duel with him.

For her part, Mackaye stuck to her la-la land story that while it may seem to the unsophisticated observer that she and Kelly were having an affair, nothing could be further from the truth.

Headline writers weren’t convinced, penning such news trumpets as “Miss Mackaye Denies Nights in Kelly’s Flat” and “Japanese Houseboy on Stand Reveals Secrets of Paul Kelly and Dorothy Mackaye.”

Mackaye admitted that she and Kelly had discussed marriage, but only “in a kidding way.” And they hadn’t been intimate but they had “played around together a little bit.” The eight women and four men of the jury scratched their heads.

The jury also learned from Mackaye that she had paid Dr. Sullivan the exorbitant fee of $500 for caring for her husband. The prosecutor insinuated that it was a bribe for helping cover up Raymond’s death.

Mackaye chirped, “Why, I once paid $300 to get a tooth pulled!”

The gallery gasped, since a tooth extraction was going for 2 bucks — tops.

The prosecutor, Robert Kemp, finally gave the jury some straight talk in his summation of the case. He accused Mackaye of being “an assassin” of her dead husband’s character.

“Her testimony proved one thing: that her heart, instead of being full of love for her husband, her home and her child, was a pool of bitterness,” Kemp said.

He then leveled his attention on the defendant.

“Kelly broke up Raymond’s home, stole the affections of his wife, then went over to Raymond’s home and beat him with his fists and caused his death,” Kemp said. “Four of the Ten Commandments have been broken in this case. Can he violate the law of God and the law of man and get away with it?”

Courtroom spectators applauded as Kemp finished.

Many observers were surprised when deliberations dragged on for several days. At the end of the third day, jurors indicated to Judge Burnell that they were deadlocked ten to two in favor of a manslaughter conviction.

Burnell suggested they sleep on it. The next morning, the verdict became unanimous.

As Burnell prepared to announce the sentence, Kelly gripped the arms of his chair with such force that his knuckles went white. He sighed as Burnell spoke: one to ten years at San Quentin. Later, while nervously puffing on a cigarette, Kelly told reporters, “I guess the jury said what they thought was right.”

A few weeks later, in a separate trial, Dot Mackaye was convicted in the cover-up and sent away to San Quentin for one to three years. Journalists covering that trial reported that Mackaye was “stunned” by the sentence.

Charges against Dr. Sullivan were dropped.

Every celebrity’s life has at least two acts, and the curtain soon rose on Act II for Paul Kelly and Dot Mackaye. She served less than two months, and he walked out of prison after two years.

By 1931, they were back in New York on Broadway — he in “Bad Girl” and “Hobo,” she in “Cold in Sables” at the Cort. On Feb. 11 that year, they were married in a civil ceremony in New York. They made a point of noting on their license that he was living at 310 W. 44th St., in the Theater District, and she was living with her daughter Mimi across town at the Hotel Tudor, on East 42nd Street.

“Sables” was Mackaye’s final performance. She retired, she later said, to focus her energy on her new husband and daughter, raised as Mimi Kelly.

The couple bought a hobby farm, which they dubbed Kelly-Mac Ranch, near the San Fernando Valley town of Northridge, California. They spent much of their time there, although Paul Kelly was in demand for both film and stage roles.

Mackaye wrote a play, “Women in Prison,” based on her experiences at San Quentin. It was made into a 1933 film, Ladies They Talk About, with Barbara Stanwyck.

On Jan. 2, 1940, Mackaye was driving home to the Northridge ranch on a foggy night when she was forced to swerve off the road to avoid an oncoming car. Her car rolled, but she managed to crawl out of the wreckage. She insisted she wasn’t seriously hurt, and a passerby drove her home. Her physician, Dr. Edward Ehret, visited Mackaye but found no injuries.

Two days later, Mackaye telephoned the doctor about abdominal pain, and he ordered her to the hospital. On Jan. 5, she suddenly lapsed into unconsciousness and died of internal injuries that had gone undiagnosed. She was 40.

In an obituary, the Los Angeles Times called her “the vivacious Dorothy Mackaye, once the toast of the theatrical world.”

Her daughter, Mimi Kelly, had a modest show business career of her own, in understudy and supporting roles from the 1940s to the 1950s, in such Broadway hits as “South Pacific” and “Finian’s Rainbow.”

Paul Kelly managed to move on without Mackaye.

On Jan. 24, 1941, he married Zona Mardelle, a bit-part actress (under the name Claire Owen) whom he met on the set of the film Flight Command a few months after Mackaye died.

His busy career became even more hectic. Kelly appeared nonstop in films — often as a cop, soldier or gangster — from 1932, when he made his Talkie debut in Walter Winchell’s Broadway Thru a Keyhole, to the mid-1950s. He also made periodic returns to Broadway, reaching a career zenith when he won a Tony Award in 1947 for his portrayal of Gen. K.C. Dennis, a conscientious military man, in the war drama “Command Decision.”

The New York Times “Mr. Kelly carried out to perfection the role of the tortured but apparently serene commander who went through with what he thought the right decision, despite all criticism.”

Kelly’s credits included more than 400 film roles and scores of stage performances. He was rarely a leading man but often had featured supporting roles. His films included such titles as San Antonio, Wyoming, Dead Man’s Eyes, Allotment Wives, Deadline for Murder, The Accusing Finger, Mr. and Mrs. North, Call Out the Marines, Flying Tigers, and his last two, Curfew Breakers and Bailout at 43,000.

Like his first wife and her first husband, Kelly did not enjoy a long life. He died of a heart attack, at age 57, on Nov. 6, 1956, after returning home to his Beverly Hills mansion, 1448 Club View Drive, from voting in the presidential election. He voted for the loser, Adlai Stevenson.

Hollywood is a small town in the hereafter, with a handful of celebrity cemeteries catering to the movie business sophisticates. But the principals in the Mackaye-Raymond-Kelly love intrigue all managed to find eternal rest far removed from one another.

Ray Raymond was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Cemetery in Glenwood.

Dorothy Mackaye, the next to go, was laid to rest at Oakwood Memorial Park, 20 miles west in the San Fernando Valley city of Chatsworth.

And Kelly was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, more than 20 miles from the other two legs of the triangle.

“Is Red-Headed Charmer,” by Alma Whitaker, Los Angeles Times, Jan. 9, 1927.

“Hollywood Actor Killed, Rival Held,” New York Times, April 19, 1927.

“Platonic Friendship Given Blame for Tragedy in Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 1927.

“Coroner’s Jury Finds Kelly Killed Raymond,” Associated Press, April 21, 1927.

“Grand Jury Indicts Dorothy Mackaye,” Associated Press, April 25, 1927.

“Paul Kelly’s Trial for Murder Starts,” Associated Press, May 9, 1927.

“Testifies Kelly Was Aggressor,” Associated Press, May 11, 1927.

“Miss Mackaye Denies Nights in Kelly’s Flat,” Associated Press, May 17, 1927.

“Japanese Houseboy on Stand Reveals Secrets of Paul Kelly and Dorothy Mackaye,” Los Angeles Times, May 17, 1927.

“Kelly on the Stand Admits Fist Fight,” Associated Press, May 18, 1927.

“Kelly Prosecutor Assails Miss Mackaye as ‘Assassin’ of Dead Husband’s Character,” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1927.

“Kelly Guilty, Asks New Trial,” Los Angeles Times, May 26, 1927.

“Kelly Sentenced to From One to 10 Years at San Quentin,” June 1, 1927.

“Dorothy Mackaye Gets 1 to 3 Years,” Associated Press, July 2, 1927.

“Miss Mackaye, Resigned But Smiling, Leaves for Prison,” Los Angeles Times, March 1, 1928.

“Dorothy Mackaye Leaves Prison,” Associated Press, Jan. 1, 1929.

“Kelly Will Be Paroled Next Friday,” Los Angeles Times, July 20, 1929.

“He’s Heading for Comeback Trail,” Los Angeles Times, Aug. 3, 1929.

“Paul Kelly to Wed Widow of Raymond,” New York Times, Feb. 11, 1931.

“Actress Pens Prison Story,” by Grace Kingsley, Los Angeles Times, Aug. 12, 1932.

“Dorothy Mackaye, Former Actress, Dies of Auto Injuries Received Near Ranch,” Los Angeles Times, Jan. 6, 1940.

“Paul Kelly, Actor on Stage, Screen,” United Press, Nov. 6, 1956.