Jesse James Hollywood — Nick Markowitz — Crime Library

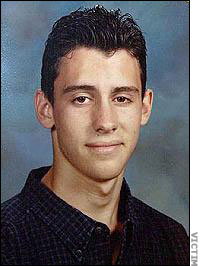

On August 6, 2000, Nick Markowitz, a handsome 15-year-old boy with an endearing widow’s peak crowning his dark brown hair, ambled down a street in West Hills, California. It was just after noon on a searing hot Sunday that would top off at 99 degrees before sunset, and Nick was in a foul mood.

The night before, he’d had a run-in with his parents when he came home at midnight with something suspicious bulging in his back pocket. His parents had good reason to be concerned — they’d caught Nick with Valium and marijuana in the past. When his father demanded to see what was in his pocket, Nick bolted out the door.

The Markowitzes were relieved to hear him return in the middle of the night, and resolved to talk to him in the morning. But when his mother knocked on his bedroom door at 11 a.m. the next day, he was gone. They would never see him again.

Around the same time that Susan Markowitz found her son’s bedroom empty, four young toughs were prowling the neighborhood in a white van looking for Nick’s older half-brother, Ben. Instead, they saw Nick.

Little did the 15-year-old know as he walked down the street on that quiet Sunday that he was on a collision course with something far more unpleasant than another confrontation with his parents.

This is the twisted tale of how a group of middle-class friends in Southern California fell under the spell of a charismatic and disturbed leader with the improbable name Jesse James Hollywood. The young men’s actions would lead to the murder of a child, Nick Markowitz, leave a community reeling from grief and shock, and spawn a four-year international manhunt.

Hollywood, 20, and Ben Markowitz, 22, had once been good friends. They grew up together, playing in the same junior baseball league as kids and working out together in the same Malibu gym as young men.

But on that hot August day, they were sworn enemies.

Ben had been part of a network of friends that Hollywood used to sell dope on consignment, but the older Markowitz boy had recently cleaned up his act. He’d moved back into his dad’s house, got a job as a machinist in the family aerospace business, and was engaged to be married, the Los Angeles Times reported.

But Ben’s decision to fly straight didn’t erase the $1,200 debt he owed Hollywood for “merchandise.” Nor did it assuage Hollywood’s anger that his former friend had foiled an insurance-fraud scam he was working: Hollywood reported one of his cars missing in an attempt to collect $36,000 for it, but Ben had alerted authorities to the scheme.

The two men carried on a months-long feud punctuated by threatening voice mails. Hollywood went to the restaurant where Ben’s girlfriend worked as a waitress and stiffed her on a bill. In return, Ben drove to Hollywood’s house and smashed a window.

On August 6, the hostilities took a sharp turn when Hollywood and his crew were driving around in another futile attempt to find Ben — who had gone into hiding — and spotted his little brother.

A few minutes earlier, Nick had turned down a ride from his uncle and cousin — who lived a few doors down from his house — as they returned from the gym. He waved them on, perhaps wanting to delay the difficult talk with his parents.

Then the white van came to a squealing stop beside the startled youngster, and four young men jumped out.

The last two days of Nick Markowitz’s life are cobbled together here from newspaper accounts, police reports, court testimony, and a 750-page grand jury transcript.

Shortly before 1 p.m. that Sunday, Pauline Ann Mahoney was driving home from church with her children when she saw a group of young men punching and kicking a boy who was cowering on the sidewalk.

“They were beating him up pretty badly,” she testified before the grand jury. “(Then) the lot of them threw him into the van, and then they jumped in, shut the door, and the van started moving.”

The family repeated the van’s license plate number aloud as they sped home, calling 911 as soon as they got in the door. An officer from the Los Angeles Police Department later visited the family with further questions. The transcripts also show that a second 911 call was made by someone who saw the abduction, but there were no details about what the witness saw, or the police response.

In one of the many distressing what-ifs that plague the case, authorities failed to track down the van until a month later.

Inside were Hollywood, William Skidmore, 20, and Jesse Rugge, 20, at the wheel. Hollywood ordered a frightened Nick to empty his pockets, taking his wallet and his pager, which bleated repeatedly as Nick’s mother tried to call him. The van stopped to pick up Brian Affronti, 20, another friend/dealer of Hollywood’s, who later testified that he quickly realized the 15-year-old was not a willing passenger.

“If you run, I’ll break your teeth,” he overheard Hollywood threaten Nick. “Your brother is going to pay me my money right now.”

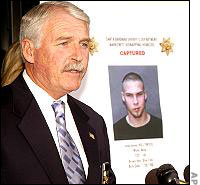

Deputy Dist. Atty. Ron Zonen

The van drove up the Ventura highway toward Santa Barbara, where the group planned to go to a party. They stopped at a house, where Nick was taken to a bedroom and blindfolded, gagged, and bound with duct tape as music thudded through the walls. Several people peeked into a bedroom during the party and were shocked to see the young captive, the Los Angeles Daily News reported. But all of them chose to close the door and party on, ignoring the terrified teen. The boys from Los Angeles had a bad reputation, and no one wanted to get on their bad side.

Hollywood got in the face of one guest as he was preparing to leave.

“Hollywood walked up to me and kind of like whispered to me… ‘Keep your fucking mouth shut, you don’t say nothing,'” he later testified.

The young man, and countless others, blindly followed Hollywood’s orders.

“You sit back and say, but for this person, but for that person… any one of them could have altered the horrible outcome of the situation simply by picking up the phone,” Santa Barbara County Deputy District Attorney Ron Zonen later told the Los Angeles Times with disgust.

A few hours after the abduction, Hollywood contacted his lawyer, Stephen Hogg, according to court papers. Hogg told him the maximum penalty for kidnapping with extortion in California was a life sentence.

“He became spooked by it, and the decision was made that they weren’t going to return (Nick),” prosecutor Zonen later told the grand jury.

Over the next two days, Nick was driven from house to house in Santa Barbara and frequently stayed at the family home of Jesse Rugge. At least two dozen people knew Nicholas was being held at various locations but did not call the police, the Santa Barbara News-Press reported.

“I mean, I just didn’t want any involvement at all,” said Richard Hoeflinger, one of the youths.

His captors fed Nick a steady diet of Valium and marijuana to keep him calm, but witnesses later told police that Nick appeared to take the drugs willingly, and that he walked freely around the house.

Jesse Rugge’s father, Barron Rugge, told the Los Angeles Times that he saw Nick watching television with his son when he returned from work one day, and that the boy appeared relaxed.

“I thought Nick was up here visiting,” he told the paper. “When I saw him, I saw him just to say ‘Hi,’ and ‘Yeah, you can stay here if you want.'”

Friends of the kidnappers later described a kind of roving party that moved wherever Nick was being held. People dropped in to smoke pot, drink booze, drop Valium and watch television alongside Nick, whom they nicknamed “the stolen boy.”

Many of the young partiers were offered immunity from prosecution in exchange for their testimony.

At one point Hollywood’s father, Jack, met with Jesse to try to persuade him to let Nicholas go, but was unsuccessful, according to the grand jury transcripts.

At another point, Nick was brought to the home of a 17-year-old girl who dressed a cut on his arm. Although she knew Nick had been kidnapped, the party-like atmosphere surrounding his abduction belied any sense he was in real danger, she later testified.

Back in Los Angeles, the Markowitzes were frantic. Susan made a spreadsheet with the addresses and phone numbers of Nick’s friends and started contacting them, the Los Angeles Times reported, while Jeff scoured local parks looking for his son.

A few exits down the freeway from the Markowitz home, the Hollywood family was also distraught. Jack Hollywood had heard from Jesse’s lawyer that his son was in deep trouble. He called Jesse and demanded to know where Nick was being held, but his son refused to tell him, the paper reported.

The 17-year-old girl who cleaned Nick’s arm also became worried. She invited one of Hollywood’s crew — Graham Pressley, 17 — to go for a walk with her and asked him point-blank whether they were going to kill Nick.

“Of course not,” Pressley’s responded, according to the girl’s testimony. But he did mention that the idea had come up: Hollywood offered Rugge money to kill Nick, but Rugge had refused it.

On August 8 — the same day the Markowitz’s filed a missing person’s report with the LAPD — Nick was brought to the Lemon Tree Inn in Santa Barbara, to what would be his final party.

On the evening of August 8, Nicholas was starting to relax.

The past 48 hours had been bizarre. He’d been terrified when his brother’s nemesis and two other guys jumped out of the van and started hitting him. But after Hollywood left the scene, things relaxed a bit, and Nick was free to wander around the houses where he was being kept, to raid the fridge and watch television. Sometimes it felt like he was more of a guest than a captive. They gave him booze and pot and it all seemed like a surreal party. He could have walked away from it all several times, but he was certain his big brother, whom he adored, show up anytime and drive him back home.

One of his abductors, Jesse Rugge, reassured him over and over again: “I’m going to take you home. I’ll put you on a Greyhound… I’m going to get you home.”

Nick made the mistake of believing him.

At the Lemon Tree Inn, Nick swam in the hotel’s large outdoor pool and flirted with girls. It was a night of teenage debauchery, the sensual atmosphere thick with pop music, rum-and-cokes, cigarettes and pot. A breeze played through the palm trees circling the illuminated blue pool. Nick was the center of attention, and he enjoyed it.

“He seemed happy,” one teenage girl later told the grand jury. “I talked to him about it, and he said that he would tell his grandkids about it someday.”

Another girl asked him why he didn’t simply leave. After all, it was dark, and there were tons of people around — the hotel was located on Santa Barbara’s main thoroughfare. He could tell the hotel employees or adult guests what was happening, and they’d take care of him, she suggested.

“I’ve taken self-defense and stuff. It’s not like I couldn’t do anything right now. I just don’t want to,” he responded. “I don’t see a reason to. I’m going home. Why would I complicate it?”

Perhaps his budding male ego was bruised by the suggestion that he couldn’t protect himself. Perhaps he wanted to appear tough to impress a sympathetic audience of teenage girls. But for whatever reason, Nick stayed put in a situation that was growing more treacherous by the moment.

The girls eventually left the party to meet their curfews and return to the safety of family life, and a short while later, there was a sharp knock on the door of the hotel room where Nick was being held.

A newcomer from Los Angeles had arrived at the scene — packing a TEC-9 automatic pistol. Ryan Hoyt, 21, owed Hollywood $1,000 for drugs. Hollywood called him with an offer: He’d erase the drug debt if Hoyt murdered Nick. Hoyt accepted the trade without flinching.

So late that night, after the guests retired, the pool closed, and silence spread through the carpeted hallways of the hotel, the stranger arrived. Lord knows how Hoyt was introduced to Nick, or what reason was given for his sudden presence. One imagines Nick looking searchingly at his kidnappers — who’d grown somewhat fond of the boy over the past couple of days, despite themselves — but that they turned away in burning shame. They knew why Hoyt was there: to take care of Jesse James’ business.

When Rugge, Hoyt and Pressley accompanied Nick to the red Ford Escort parked in the inn’s lot, he was heavily sedated with marijuana and Valium, according to testimony. He had a hard time sitting straight as the car drove 30 minutes up Highway 154, a scenic route that winds through a lush bucolic landscape of orchards, ranches and vineyards. The car turned into Los Padres National Forest and stopped beside a trailhead.

Pressley knew the spot well — he frequently hiked there with friends, and earlier that day he’d been there with a shovel to dig a hole. While Pressley waited in the car, Rugge and Hoyt dragged Nick up a rugged dirt trail to a popular campsite called “Lizard’s Mouth” that affords sweeping views of the Pacific Ocean. There, under a clear starry sky, the two men used duct tape to cover Nick’s mouth and to bind his hands behind his back. They guided him to the shallow grave that Pressley had dug beneath a large manzanita bush.

Only his executioners know if Nick was lucid enough during his final moments to comprehend what was happening to him. He didn’t have much time to contemplate it. One of the men hit Nick over the head with a shovel, according to media accounts, and then Hoyt took out the semiautomatic and stood over him. He squeezed the trigger, drilling nine bullets into Nick’s abdomen and chest, before the gun jammed. The two men dumped Nick’s body and the gun into the grave, threw dirt and leaves over it, then ran back to the car. Police would later paint an eight-foot boulder that loomed over the spot with a large orange X to mark the scene of the crime.

Rugge got physically ill after the shooting, but Hoyt marveled at how easy it was.

“That’s the first time I ever did anybody. I didn’t know he would go that quick,” Hoyt said when he climbed back into the car, according to a detective who interviewed the suspects.

At the time his followers were killing Nick, Hollywood was in Los Angeles, celebrating his girlfriend’s birthday at an Outback Steakhouse, investigators later learned.

Four days later, hikers noticed a stench beside the trail in Los Padres National Forest, as well as pieces of clothing poking out of the forest litter. They called the Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Department, which identified the body as Nick’s.

It took more than a week before anyone familiar with the “stolen boy” contacted authorities. Finally, one of the teenage girls who saw Nick alive at Rugge’s house saw a news report about the murder and talked to an attorney, who in turn notified the police.

The suspects grew up in an affluent and close-knit community west of Los Angeles called “West Hills.” Hollywood and Markowitz were in the same junior baseball league together, and Jesse James’ father, Jack, was their coach. His mother, Laurie, attended most of her son’s games and practices. It was the kind of apple-pie environment where parents dote on their children, cheering in the stands and taking turns flipping burgers in the snack bar.

The Hollywoods moved to Colorado briefly to start a restaurant in the mid-1990s, but returned to their old neighborhood in 1995, the Los Angeles Times reported.

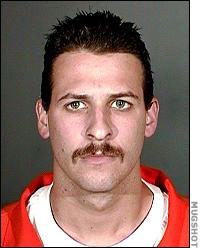

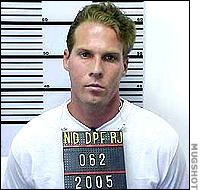

Jesse James Hollywood is a little guy — only five-foot, four-inches tall and 140 pounds. But he compensated for his frame with arrogance and swagger.

His former baseball coach at El Camino Real High School described him as an “emotional kid” who was expelled from school for blowing up at a teacher at the end of his sophomore year.

“Let’s just say his behavior was… very extreme and out of line,” Bob Ganssle told the paper.

After the incident, Hollywood transferred to Calabasas High School, where he played on the varsity baseball squad until he injured his back and leg and was forced to quit.

Investigators believe Hollywood started selling dope at least a year before Nick’s murder. Soon, his business was booming to the point where he recruited his friends to peddle pot for him.

At 19, he bought a three-story white stucco home for $200,000, just a few blocks away from the Markowitz family, making the $41,000 down payment in cash. He drove a black Mercedes and a blue sports car.

Neighbors often saw him in the front yard hanging out with a group of young men similarly dressed in jeans and tank tops, smoking in the shade of large elm tree. In the backyard, he kept two pit bulls. They also noticed strange goings-ons, cars that would pull up to the house night and day, drivers who would dash inside for a minute before leaving again.

“Everyone knew it was drugs,” a young man who lived in the neighborhood told the Los Angeles Times. “I mean, all the nice cars. He didn’t really go to work or nothing.”

Despite the apparent drug activity, detectives said Hollywood had no drug record, although he had been charged as a minor with possessing alcohol and on another occasion with resisting arrest. That a boy named “Jesse James” would grow up to be an outlaw seems less than ironic, although his family told the press he was named after an uncle, not the infamous gun-slinger.

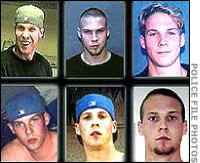

On Wednesday, August 16, four suspects — minus Jesse James — were arrested. At their arraignment at the Santa Barbara Superior Court, all four pleaded not guilty to charges of kidnapping and murder. Hollywood was charged in absentia under a California law that allows any participant in a kidnapping that ends in a homicide to be charged with murder.

William Skidmore, who was convicted three times in prior years — twice for being under the influence of controlled substance and once for resisting arrest — was eventually sentenced to a nine year term for his part in the crime.

Jesse Rugge — who was convicted in 1996 of a felony for carrying a concealed knife to school and in 2000, for driving under the influence — was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole in five years.

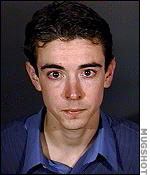

And 17-year-old Graham Pressley — who had no prior criminal record and was turned in by his parents — was sentenced to the California Youth Authority’s Ventura facility until his 25th birthday.

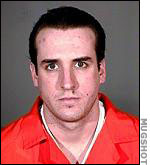

Triggerman Ryan Hoyt — who also had no prior criminal record, not even a speeding ticket — was found guilty of first-degree murder in November 2001. Today Hoyt sits on Death Row at San Quentin, waiting to die by lethal injection.

On the same day that Hoyt was sentenced, two Los Angeles cops were disciplined for their shoddy work in handling the case. The LAPD found officers Donovan Lyon and Brent Rygh guilty for failing to appropriately investigate the 911 calls related to the kidnapping.

Meanwhile, police fanned across the region to search for the posse’s leader.

Astonishingly, only three days after he ordered Nick’s murder, Hollywood appeared in a Ventura courtroom on charges of possessing alcohol, the Ventura County Star reported. Court records show he was cited on May 25 for underage drinking at Sycamore Canyon State Park. He pleaded guilty and was fined $265.

Soon afterward, Hollywood was seen dragging luggage from his home, the Los Angeles Times reported. He told a neighbor he needed to leave in a hurry “because too many people know where I live.”

Nervous that the cops were closing in on him, Hollywood withdrew $25,000 from a bank account, bought a model-year Lincoln Town car, and sped out of California with his girlfriend. The couple stayed at the opulent Bellagio Hotel and Resort in Las Vegas on August 15. The next day, they drove to Woodland Park, Colorado, where Hollywood’s godfather, 48-year-old Richard Dispenza, taught physical education at a local high school and coached football and girl’s soccer.

His girlfriend flew back to California, and Hollywood stayed with Dispenza for at least one night, according to the Rocky Mountain News. The next morning, Dispenza drove Hollywood to a Ramada Inn off Interstate 25 in Colorado Springs. He stayed there for three days and, after checking out that Sunday morning, would not be seen for four and a half years.

“The longer this goes on, the more dangerous he becomes,” Detective Susan Payne of the Colorado Springs PD told the Colorado Springs Gazette. “The concern [is that] anyone who crosses his path could be in danger. Each hour that goes by, he becomes more dangerous because he’s that much closer to being caught.”

More than 300 mourners attended Nick’s memorial service at Eden Memorial Park chapel in Mission Hills in 90-degree heat, stunned that a 15-year-old boy had been killed over his brother’s drug debt. People packed the chapel and spilled outside, listening to the service over an intercom.

“There are deaths such as this when we can’t shake an angry finger at God and say, ‘Why?’ We can only look at ourselves,” Rabbi James Lee Kaufman told the crowd.

Barbara Police Department

Six young pallbearers, three of them sobbing, carried the casket up a grassy hill to the grave site, the Los Angeles Times reported.

“You were always a call away when I needed you,” Zach Winters, 16, told the assembly. “Things aren’t going to be the same without you. All I can say is, I love you, man. We’ll always be friends for life.”

Ben Markowitz skipped the funeral out of respect for his stepmother, he told KNBC-TV Channel 4.

“I wish I was the one who was gone,” he told the news station. “I couldn’t even fathom anyone doing that (to him), especially people that I grew up with, laughed with, cried with,” he said, struggling to compose himself. “I mean, these are, like, my friends.”

Later, police learned that on August 22, Hollywood was driven from Colorado to California by a childhood friend, whom they did not identify. On the morning of August 29, Santa Barbara sheriff’s detectives confiscated several bags of evidence from the home of Hollywood’s parents. That evening, a Los Angeles SWAT team surrounded Hollywood’s house in a quiet San Fernando Valley neighborhood, blocking streets and using bullhorns to warn neighbors to stay locked inside their homes. Police helicopters buzzed the rooftops as police called out for Hollywood to surrender.

At one point, a drunken man stumbled out of the front door with his hands over his head. It was not Hollywood, but one of his acquaintances, who was crashing at the house.

“This is nuts, just nuts,” one neighbor told the Daily News, as she waited several hours behind a police barricade. Her two teenage sons were trapped inside their home half a block away.

Police fired tear gas into the house at sunset and forcibly entered it, but found it empty. They did, however, discover the white 1991 Chevy van they believed was used to kidnap Nick.

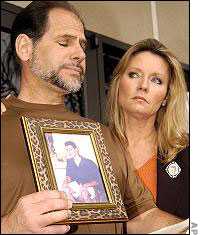

A knock on their front door shattered the lives of the Markowitz family.

Susan Markowitz, 41, the second wife of Jeffrey Markowitz, described herself to the Los Angeles Times as a “stay-at-home mom whose job had been taken away.” She was very close to her son Nicholas, and the two even kept a journal together.

After learning that more than two dozen people saw her beloved son alive during his last two days, yet failed to call the cops, she became outraged, then despondent. She tried to kill herself twice, she told the paper, but eventually found strength by focusing on the capture of her son’s killers.

The Markowitzes sued Hollywood and 31 others over Nick’s death, alleging that dozens of people could have helped Nick escape. They settled with 14 defendants, including the LAPD, for $350,000.

She tacked up “wanted” posters for Hollywood around town. The Markowitz family offered a $50,000 for information leading to his arrest, adding to the $20,000 award offered by the FBI.

She attended hundreds of courtroom proceedings for the captured suspects, clutching her son’s leather bomber jacket as a kind of security blanket while she listened to testimony maligning her son’s character or detailing his brutal death. The only proceeding she missed, she told the Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles, coincided with what would have been Nick’s graduation from El Camino High School, which she attended to pass out “In Memory of Nick” key chains.

The stress of her ordeal at manifested itself in severe back pain that sent her to the emergency room. She also gained 65 pounds. After his death, she turned the family home into a shrine to her only child, hanging up poster-sized pictures of her son and displaying his personal belongings around the house, including his baby toys and bar mitzvah gifts.

She told the Journal that it was hard for her not be bitter toward her stepson, Ben, and admitted there was friction in her 18-year marriage because of it.

“Nick died for his brother Ben,” Markowitz told the paper. “He did nothing to escape, because he felt his brother would come and save him. In my opinion, Ben has done nothing in memory of that.”

The Jesse James Hollywood case aired on the true crime television shows America’s Most Wanted and Unsolved Mysteries, and although the shows generated hundreds of leads, none of them panned out.

But the FBI, which was monitoring phone calls made by Hollywood’s parents, did get a solid lead in March 2005 when they learned that Hollywood’s cousin, a woman he hadn’t seen in years, was planning to pay him a visit — in Brazil.

Brazil has long been a haven for international fugitives. Nazis, former dictators and disgraced mafiosos have all been drawn to the South American country, where the living is easy and the extradition laws are lax. Included in this dubious roster is Josef Mengele, the so-called “Death Angel” who performed hideous experiments on children at Auschwitz concentration camp, and who drowned while swimming at a Brazilian beach in 1979. Ronald Biggs, who robbed $50 million from a mail train traveling between Glasgow and London in 1963 in a crime that became known as “The Great Train Robbery,” was another. (In 2001, an old and decrepit Biggs voluntarily returned to England — and prison — in exchange for free health care and a chance to see his family.)

Authorities soon learned that Hollywood was living under the alias Michael Costa Giroux and claimed to be a native of Rio. He and his girlfriend Marcia — a woman 15 years his senior — first lived in Copacabana, Rio’s glitzy beach and nightlife district immortalized by the Barry Manilow song, where he subsisted by passing out promotional fliers for a local bar.

At some point, the couple moved to a fishing village called Saquarema, an internationally known surfers’ paradise an hour east of Rio. They lived in a yellow house with a high wooden gate, and Hollywood was seen jogging along the idyllic white beaches with his two pit bulls.

He tried to keep a low profile, the Los Angeles Times reported.

“He liked to socialize, but he had an explosive temper,” said Wanderley Martins, a Federal Police inspector and local Interpol agent, told the Associated Press. “He fought with bar owners over his beer tab. He was like that.”

Neighbors told the Los Angeles Times that he often quarreled with his girlfriend. Apart from barbeques held with out-of-town guests, Hollywood rarely talked to his neighbors.

“He always had his head down… he never said anything,” Walma Lindberg da Silva, who lived next door, told the paper. “I told my husband I thought there was something wrong with him.”

After learning he was in Brazil, the FBI sent photographs and videos of Hollywood to local authorities and the trap was set. Hollywood arranged to meet his cousin at an outdoor mall in Saquarema. Hollywood, now 25, and his then 7-months-pregnant girlfriend, had just sat down at an outdoor table when a plainclothes policewoman walked toward him, smiling and calling his name. When he stood to greet her, she identified herself to the dismayed Hollywood as a cop.

As the Brazilian police drove the short blond man to their headquarters in Rio de Janeiro, it became clear from his fumbling Portuguese that he was not Brazilian. At the station, they confirmed his ID card was fake, but he insisted for two hours that there had been some kind of terrible a mix-up.

“Portuguese is a difficult language,” Federal Police agent Kelly Bernardo, who made the arrest, told the Daily News. “He didn’t speak really well, but we could understand what he said. He tried to maintain his story that his name was Michael. Then, in the end, he said he was Jesse James Hollywood.”

In interviews, Brazilian police said they believed Hollywood had been living under an assumed name in their country for four years, and supported himself by teaching private English classes and walking dogs. But his biggest cash flow, they said, came from his father, who wired him $1,200 a month.

On the same day that Hollywood was arrested in Brazil, his father was arrested in Santa Barbara on suspicion of manufacturing GHB, the so-called “date-rape drug.” Although the case was eventually thrown out — the 50-year-old had the ingredients to make GHB and a recipe, but no evidence of the finished product was found — he was kept in custody on a 2002 arrest warrant from Pima County, Arizona, for a marijuana-related charge.

On March 10, 2005, Hollywood landed at Los Angeles International Airport and was immediately taken to the Santa Barbara County Jail. He appeared briefly in the Santa Barbara Superior Court the next day, where he pleaded not guilty to the charges against him.

Of course the Hollywood story had to be made into a movie. Sex, drugs, murder, teenagers gone wild: the tale had it all. Director Nick Cassavetes took up the challenge, telling the New York Times he became interested in the story because his eldest daughter was a student at the same high school Hollywood attended.

Beyond the superficial drama, he told the paper, he was interested in exploring how boys who want to appear tough can box themselves into behaving that way. That’s what he imagines happened during Nick’s kidnapping — that the young men egged on each others’ tough-guy images until finally someone took it too far and murdered Nick Markowitz.

“We watch violent images on TV, we revere violence, but we’re not raised violently,” he told the Times. “And when we’re put in a situation, we act how we think we should act, as opposed to how we’ve been trained to or how we have a history of acting.”

After he finished shooting half of the $13 million flick Alpha Dog — which stars Justin Timberlake, Bruce Willis, and Sharon Stone — Hollywood was arrested in Brazil, and he had to go back and revise the storyline based on the emerging facts.

But the setbacks didn’t end there. He was subpoenaed by Hollywood’s defense lawyer, James Blatt, who accused prosecutor Ron Zonen of misconduct for showing Cassavetes nonpublic documents related to the case. Blatt asked the California Supreme Court to have Zonen removed from the case; the court is slated to make a decision on the case by May 2.

Furthermore, Blatt has threatened to seek an injunction against the release of the movie, saying it would taint potential jurors.

“Names are changed, but they advertised it as a true story and everyone’s going to know it’s the Jesse James Hollywood story,” Blatt told USA Today.

Alpha Dog premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January to mixed reviews. New Line Cinema had originally scheduled the release for April, but now says the date is “to be determined,” according to press reports.

Associated Press. “Over 20 knew of teen’s kidnapping, transcripts show.” November 30, 2000

Chu, Henry, and Solomon Moore. “Fugitive kept a low profile in quiet Brazilian beach town,” Los Angeles Times. March 11, 2005

Connel, Sally Ann. ” Lawyer Allegedly Told of Kidnap,” Los Angeles Times.

Nov 17, 2000

Fausset, Richard. ” Reports Outrage Victim’s Mother,” Los Angeles Times. Nov 30, 2000

Fox, Sue. “Kidnap, Killing of West Hills teen unfolds in testimony,” Los Angeles Times.

Dec 10, 2001

Fox, Sue. “Judge says fugitive’s lawyer must testify,” Los Angeles Times. May 10, 2001

Goldberg, Orith and Lisa Van Proyen. “Fugitive search stuns neighborhood,” Daily New of Los Angeles. August 30, 2000

Guccione, Jean. “Parents of Slain Teen Settle,”Los Angeles Times. May 3, 2002

Guccione, Jean. “Family of Slain Boy Files Suit Against 32 People,” Los Angeles Times. Aug 10, 2001

Guccione, Jean. ” Victim’s brother tries to make sense of slaying,” Los Angeles Times.

July 26, 2001

Halbfinger, David. “Filmmaker is snarled in legal web,” New York Times. January 18, 2006

Hethcock, Bill. ” Teacher spared prison for aiding slaying suspect,” The Colorado Springs Gazette. May 19, 2001

Kasindorf, Martin. “Murder case is like a movie, and that may be a problem,” USA Today. March 27, 2006

Kelley, Daryl. “Teen was slain over brother’s drug debt, official say,” Los Angeles Times.

August 18, 2000

McGinnis, Shawn. “Jesse James Hollywood tires to dump prosecutor,” KTLA News. March 7, 2006

McCarthy, Marianne. “Convicted murderer sentenced as a juvenile,” Daily News of Los Angeles. February 12, 2003

McCarthy, Marianne. “4th defendant convicted in valley youth’s murder,” Daily News of Los Angeles. November 21, 2002

McCarthy, Marianne. “Jesse James Hollywood faces judge,” Daily News of Los Angeles.

March 12, 2005

McCarthy, Marianne. “Prosecutor: teen key in boy’s slaying,” Daily News of Los Angeles.

October 31, 2002

McCarthy, Marianne. “Man says he was forced to dig Markowtiz’s grave,” Daily News of Los Angeles. October 31, 2002

McLean, Bruce. ” Suspect had been in court three days after boy’s death,” Ventura County Star. August 19, 2000

Meyer, Jeremy. “Manhunt heats up,” The Colorado Springs Gazette. August 24, 2000

Miller, John. “Jesse James Hollywood — life on the run,” Daily New of Los Angeles.

March 11, 2005

Muello, Peter. “Brazil deports American wanted for kidnapping,” Associated Press.

March 10, 2005

San Luis Obispo Tribune. “Murdered teen invited to escape, women say.” July 13, 2002

Reich, Kenneth. “Two Officers Guilty of ‘Minor Breach of Policy,’ Board Finds,”

Los Angeles Times. Nov 21, 2001

Rhone, Nedra. “Brother of Slain Teenager Arrested in Armed Robbery Case,” Los Angeles Times. Feb 9, 2001

Risling, Greg and Sue Fox. ” SWAT Lays Siege to House but Fugitive Is Not There,” Los Angeles Times. Aug 30, 2001

Werner, Erica. “Murder suspect remains at large,” Contra Costa Times. August 7, 2001