Gary Krist is brilliant criminal who kidnapped daughter of President Nixon’s friend the Crime Library — The Criminal Brain — Crime Library

Gary Steven Krist regards himself as the Einstein of crime.

But Albert Einstein, with his measly theory of relativity, was a one-trick pony by comparison.

Krist’s criminal accomplishments are far more diversegrand theft auto, prison escape, fraud, kidnapping for ransom and, most recently, cocaine importation and illegal immigrant smuggling.

He began by stealing cars before he could legally drive them. He had been incarcerated in three different states by age 18. He broke out of prison in California and fled across the country, where he managed to live under a pseudonym while working at two prestigious universities.

Next came his magnum opus, the “perfect crime” he planned while still a callow stripling.

In one of the most audacious and notorious crimes of the 1960s, at age 23, he kidnapped a young heiress in Atlanta and buried her alive in an underground capsule he had designed.

While the country held its breath, Krist and his mistress sidekick extracted a $500,000 ransom from the woman’s father, a Florida real estate magnate and friend of President Nixon.

Miraculously, the young woman survived a harrowing 83 hours underground.

But Krist wasn’t as clever as he thought.

His getaway plan collapsed, and he was apprehended after a dragnet pinned him down on a Florida mangrove island.

Krist narrowly escaped a death sentence and was sent away to prison “for life,” according to the judge’s decree.

But life was short in those days.

Krist pulled one of the great flimflams in American prison history by convincing a gullible Georgia parole official that he was rehabilitated.

Vowing to become a missionary, Krist waltzed out of prison after barely 10 years of confinement for a sickening crime that could have cost him his life.

His missionary work didn’t pan out. Although it took awhile, Krist’s path inevitably led back to crime.

In the spring of 2006, a police greeting party was waiting at a dock near Mobile, Ala., when Krist returned from a two-month trip aboard a rented sailboat.

Authorities found 38 pounds of cocaine on board, as well as four illegal South Americans who had paid handsomely for passage to the United States.

An investigation revealed that he had been selling the cocaine in Georgiathe state that naively gave him the free pass out of prison years ago. And in an eerie echo from the kidnapping case, Krist had constructed an underground cocaine-processing lab at his home near Auburn, Ga.

Now 61, he has pleaded guilty to multiple federal offenses and faces another life sentence. His next departure from prison may be in a pine box.

Gary Krist lacked education, family direction, motivation, money and a moral compass.

But he never lacked self-confidence. His over-the-top ego is one of the factors that makes the life story of the “Einstein of crime” so captivating.

Gary Krist was born April 29, 1945, to a fishing family. His father, James, ran a boat out of Pelican, Alaska, a scruffy little port villageaccessible only by sea or airabout 80 miles north of Sitka.

During the long salmon and shrimping seasons, the sea consumed the lives of Krist’s parents, so Gary and his older brother, Gordon, spent vast stretches of their childhoods in the care of family friends.

He was a miserable boy. His father was aloof and his mother distracted even when they weren’t out to sea.

Trouble visited early.

By age 9, Krist had a reputation as an incorrigible thief. He would steal anythingcoins, tools, penny candyeven if he didn’t need it.

Perhaps he yearned for attention.

He eventually graduated to stealing cars. At age 14, Krist was caught filching a car in Seward, Alaska. That state had failed to reform the boy in delinquent programs there, so he was sent away under federal supervision to a juvenile facility in Ogden, Utah.

After nearly a year thereincluding a brief escape and a car thefthe was allowed to return to Alaska and attend high school in Sitka.

Krist did well academically during his two years there. He was recognized as a bright kid and a quick study. After graduation, he returned to Ogden, hoping to pursue a medical degree at the University of Utah.

It was a pipe dream. He didn’t have the self-control for college.

From puberty to young adulthood, Krist’s life was a dizzying blur of car thefts followed by inevitable incarceration.

In August 1963, a few weeks before college classes were to begin, he stole an El Camino and fled to Oakland, Calif., abandoning a pregnant girlfriend in Ogden.

After just a few days in California, Krist wrecked a stolen MG in Ventura and was sent away to a state juvenile jail.

During his 14 months there, Krist spent idle hours planning his magnum opus crime.

He believed that most kidnappings failed due to poor planning and execution. He vowed to do it right.

Krist decided the perfect target would be a young woman. Children are too much of a hassle, he reasoned, and abducting a male victim could be a physical challenge.

Holding a victim while awaiting ransom can be another challenge. Krist conjured a solution: Bury the victim alive in a secure tomb.

He worked out dozens of other detailsthe modes of contact with the victim’s parents, how and when the ransom drop would be made, getaway plans and contingencies.

Krist, still just 18 years old, resolved to bide his time and wait for the right moment to pull off the crime.

He was freed on Dec. 4, 1964, and made his way to Palo Alto, where his brother was studying at Stanford University.

In March 1965, he married Carmen Simon, a young woman he met at a Redwood City rolling skating rink.

Within weeks, he was back in jail for car theft, serving a four-month sentence.

Krist’s car thievery was beyond self-destructive. It was obsessive, even sociopathic.

He stole cars from parking lots, from driveways, from car dealerships. If he saw a key in an ignition, he considered it a gift. He had to steal that careven if he had nowhere to drive it, and even though he knew he would get caught again.

He couldn’t help himself.

Krist celebrated his first wedding anniversary by beginning a five-year prison sentence for auto theft. His son Vince was born while he was locked up.

But after just eight months, Krist got an early release by scaling two fences at a prison in Tracy, Calif., and running for his life.

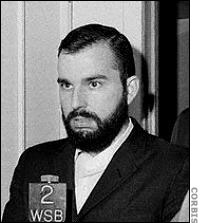

He fled with his wife and infant son to Boston, where he grew a beard to conceal his features and assumed a new identity as George Deacon.

He landed a $7,500-a-year job as a research assistant at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by answering a want ad. For 18 months, he and Carmen led a conventional lifestylehis fugitive status notwithstanding.

They lived in a trailer park in Norton, Mass., outside of Boston, and had a second son, Adam.

At work, Krist earned a reputation for picking up information quickly. He could read a basic primer on cryogenics or some other obscure facet of physics and manage to have intelligent discussions about the subject with MIT professors who had dedicated entire careers to the specialization.

But he could also be obnoxious, crowing about his stratospheric IQ or conjuring fantastic tales about his alleged accomplishments.

Conflicts arose that made Krist nervous about being discovered as an escaped felon. Through an MIT mentor, he moved on in the summer of 1968 to the University of Miami’s Institute for Marine Researchstill under the name George Deacon.

He and his family rented a mobile home at the Al-Ril Trailer Court on Northwest 14th Avenue in Miami.

At a salary of $8,500 a year, Krist became a marine technician on the institute’s small fleet of research boats.

In September 1968, he was a boat hand on a two-week research trip to Bermuda by a group of graduate students. During the trip, he began an affair with Ruth Eisemann Schier, 26, a bright, petite and pretty grad student from Honduras. Her parents were Austrian Jews who fled to Central America to avoid Nazi persecution.

Krist, a burly 6-footer, towered over the 5-foot-2 Eisemann. But Eisemann, who was described as “sweet and charming,” could hold her own with the overbearing Krist.

She spoke Spanish, German, English and French, and she had a quick smile and a European flair.

To Krist, the hot-blooded Eisemann was the antidote to a sex life with Carmen that had gone stale after the births of their two sons. To Krist’s delight, Eisemann was willing to experiment in the bedroom. Among other things, they enjoyed taking risqué Polaroids of one another.

Three weeks before Christmas, Krist informed his wife that he no longer loved her. She packed up and moved back to Redwood City with the children.

Carmen Krist later told reporters she bore no grudge against Krist. She wasn’t surprised about his mistress because he often lobbied his wife to allow him to lead a sexually “open” lifestyle. But she wasn’t into it.

“Gary doesn’t want to lead a mediocre life,” she said. “He wants to be remembered.”

Eisemann enthusiastically took her place in Krist’s trailer.

He soon let her in on his get-rich-quick kidnap plan. They would take the $500,000 ransom and flee to Europe, he told her, where they would live happily ever after.

In the fall of 1968, Gary Krist searched methodically for the perfect victim for his perfect crime.

In his memoir, “Life,” Krist claimed that he spent weeks in the Miami public library, poring over social registers and newspaper clippings to find a target. He winnowed a list of 100 possible victims to just 10, then eliminated those one by one until a single name was left: Barbara Jane Mackle.

Her father, Robert Mackle, 57, co-owned the Deltona Corp., a pioneer of planned communities in Florida, with his brothers Elliott and Frank Jr.

Frank Mackle Sr. had developed Key Biscayne as cheap housing for returning soldiers in the 1950s. The modest $10,000 houses became known as “Mackles.”

Frank Sr.’s sons replicated his success on Key Biscayne with community development projects across the Sunshine State, including Deltona, now a city outside Orlando with 75,000 residents; Spring Hill and Citrus Springs, north of Tampa; St. Augustine Shores on Florida’s northeast coast; Sunny Hills, near Panama City, and the ritzy Marco Island, south of Fort Myers.

The Mackle brothers had become players in politics when Richard Nixon bought a modest “Mackle” on Key Biscayne that later became the unofficial winter White House.

Robert Mackle forged a friendship with both Nixon and his Key Biscayne neighbor and advisor, Bebe Rebozo.

Krist learned that Robert Mackle lived with his family in a mansion on a golf course at 4111 San Amaro Drive in Coral Gables, south of Miami. He and his wife, Jane, had two children, Robert Jr., 24, and Barbara, 20.

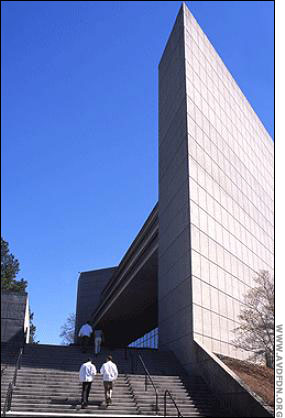

Krist’s research revealed that Barbara, a tall brunette, was a junior coed at Emory University in Atlanta.

A newspaper profile of Mackle placed the value of his firm at $65 million.

Gary Krist didn’t want all of Mackle’s money. Just $500,000 of it.

Barbara Mackle was not feeling well as Christmas approached in 1968.

The Hong Kong flu, raging across America, had arrived at Emory. She was scheduled to take semester-ending exams, then fly home to Florida on Dec. 20 to spend Christmas break with her family.

She phoned her mother in Coral Gables on Dec. 12 to say she was terribly sick with the flu but intended to stay at school to complete her exams.

Jane Mackle flew to Atlanta to remove her daughter from campus, where the infirmary was overflowing and medications were scarce.

On Dec. 13, they checked into a Rodeway Inn in Decatur, Ga., at the edge of the Emory campus. Under her mother’s care, Barbara managed to study and travel to campus intermittently for exams.

Coincidentally, Krist and Eisemann arrived in Atlanta at about the same time as Jane Mackle.

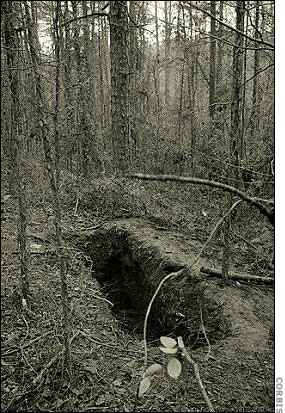

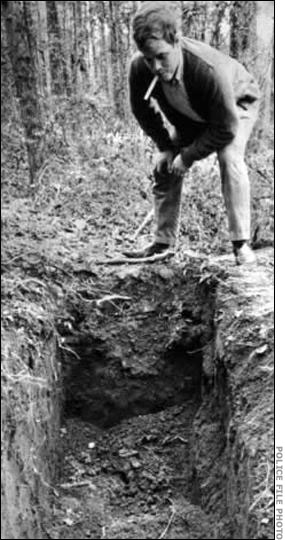

Krist had built his underground capsule in a trailer at the University of Miami. He and Eisemann had disposed of their possessions in Miami, then hauled the capsule 12 hours north in a Volvo station wagon. They located a remote spot in the piney woods outside Atlanta and spent a day digging a hole in the clay soil to install the capsule.

Locating the victim proved simple by comparison.

Krist, posing as a “scholarship investigator,” learned the name of her dormitory by merely asking at the admissions office. A dorm mate told Krist that Mackle was staying with her mother at the Rodeway Inn. He identified their room No. 137 by staking out the motel.

Krist startled the women awake with a knock at 4 a.m. on Tuesday, Dec. 17. He said he was a police officer and that Barbara’s fiancé, Stewart Woodward, had been hurt in a car accident.

When Mrs. Mackle opened the door, Krist and Eisemannwearing ski masksbarged in and brandished an assault rifle.

They tied up Jane Mackle and knocked her out with chloroform, then snatched the daughter, dressed only in a flannel nightgown.

Krist drove 20 miles north, to a spot near Duluth, Ga. He exited the highway at South Berkeley Lake Road, then turned off again into a patch of woods, easing the Volvo 100 feet back through the trees.

Krist got out and pulled away tree limbs that obscured the capsule. And Barbara Mackle got her first look at the terror that awaited her.

The capsule was roughly 3 feet wide, 3 /2 feet deep and 7 feet long. It was constructed of plywood, and the interior was lined with fiberglass. The corners were reinforced with steel brackets.

Krist popped off the lid and launched into a proud explanation to Mackle of how he had equipped the tomb with everything she would need to keep her safe until he received the ransom.

Krist pointed out that the capsule had food, water (laced with sedatives), a fan, a lamp, a blanket and a sweater. Two flexible plastic pipes to the surface brought in fresh air.

The woman’s eyes were like saucers.

“No, no, no!” she cried.

She begged Krist to take her anywhere else, but not to bury her. According to Krist, she repeated one phrase like a mantra: “I’ll be good!”

Krist held the victim’s arms while Eisemann applied a chloroform-soaked towel to her face.

She was drowsy but not knocked out as they lowered her into the tomb.

She cried out again and again as Krist fastened the lid with 14 screws, then buried her beneath hundreds of pounds of dirt and camouflaging branches.

Mackle listened through the air tubes as the shoveling stopped. She heard footsteps, followed by the sound of a car starting and driving away.

She later wrote, “I started screaming and pounding to try to get out. With my fists I hit the walls as hard as I could. With all my strength I braced and pushed … I was screaming, ‘God, no, you can’t leave me!'”

It was 8:30 a.m. on Dec. 17.

She lay there petrified, her chest heavingbelow ground in a claustrophobic capsule that offered no chance for escape.

Her life was in the hands of her kidnappers. As she regained composure, she took stock of her surroundings. Beneath a Kotex box she found a long, typed note from Krist that proudly explained his wonderful hostage-holding device.

“DO NOT BE ALARMED. YOU ARE SAFE … YOU’LL BE HOME FOR CHRISTMAS ONE WAY OR THE OTHER.”

Among other things, Krist bragged in the note that his ingenious capsule included a battery that would operate her light and fan for a full 11 days.

He was wrong. The battery crapped out in just three hours.

Krist phoned the Mackle home that morning to direct the family to a set of instructions he had buried ahead of time under a rock in their yard.

If Mackle agreed to pay the $500,000 ransom, he was to place a classified ad in the next day’s Miami Herald.

Krist and Eisemann spent the day preparing the ransom pickup and their escape. They bought plane tickets to Chicago and a small boat.

The next morning, Dec. 18, the ad appeared in the paper:

“LOVED ONE: Please come home.

We will pay all expense and meet

you anywhere at any time. Your Family.”

Late that night, Krist phoned the Mackle home with ransom drop instructions. Robert Mackle was to leave the money on a seawall along Fair Isles Causeway at Biscayne Bay, a few miles from Mackle’s mansion in Coral Gables.

Krist waited nearby, bobbing in a skiff in the bay. He planned to race to shore, grab the cash and jump in a getaway car, the Volvo, driven by Eisemann.

But as Mackle made the drop, two cops happened by, and the pickup was aborted, with Krist fleeing on foot and Eisemann abandoning the Volvo.

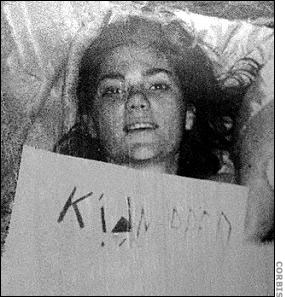

It was a fiasco. The car contained a trove of information about the kidnappers, including Eisemann’s passport, their checkbooks, documents that revealed their past addresseseven a collection of lacy bikini panties and racy nude Polaroids of both Krist and Eisemann. Police also found a Polaroid of Mackle holding a sign that bore the word “Kidnapped.”

Krist and Eisemann decided to split up, planning a rendezvous in Austin, Texas, as a prelude to their escape to Europe.

Eisemann boarded a bus heading west while Krist pressed a second ransom payment plan. He rented a car and phoned Mackle at 10:35 that night.

He ordered a new money drop on Southwest Eighth Street, at the edge of the city. The second drop went as planned, and Gary Krist had his $500,000.

He was richbriefly.

By the time Krist picked up the cash, the FBI already knew the identities of both kidnappers. Warrants were issued, although authorities had no good idea of where to find the kidnappers.

That would change when Gary Krist made a rookie mistake.

Krist decided his safest escape would be by boat. He planned to cross Florida via canals, then buzz across the Gulf of Mexico to the Texas rendezvous.

The morning after receiving the ransom, Krist pulled into D & D Marine Supply in West Palm Beach and purchased a 16-foot motorboat, using the name Arthur Horowitz.

But he paid for the boat with $2,240 in $20 bills.

The Mackle kidnapping was front-page news across the country, and everyone in America knew that morning that the ransom had been paid in $20 bills to a burly, bearded man.

At D&D Marine, owner Norman Oliphant thought it was curious that Arthur Horowitz, burly and bearded, had a thick stack of $20 bills.

He called police just after “Horowitz” towed the boat off the lot at noon.

An hour later and nearly 15 hours after the ransom pickup Gary Krist stopped at a payphone and called the Atlanta FBI office to leave directions to Barbara Mackle’s burial site.

An army of agents raced toward Duluth. The first agents who found the spot spoke to Mackle through the air tubes, then frantically clawed at the earth with their bare hands to free her.

“She kept saying, ‘Don’t leave me,'” the FBI’s Ange Robbe told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “We assured her we wouldn’t.”

She was finally freed after 83 hours underground dehydrated, stiff and 10 pounds lighter.

Mackle told her rescuers, “You are the handsomest men I’ve ever seen.”

She was whisked back to Miami in her father’s private jet. During a brief appearance for the press, Mackle insisted her kidnappers had treated her humanely and that she was feeling “absolutely wonderful.”

Krist turned up that night, Friday, Dec. 20, at the first lock of the Florida Intercoastal Waterway near St. Lucie.

He gave the lock tender his boat registration information, then continued west across Florida through the St. Lucie Canal, across Lake Okeechobee and through a series of locks leading to the Caloosahatchee River in the Fort Myers area on the west coast of the state.

Krist covered more than 100 miles by daybreak Saturday. But the tender at the final lock before the Caloosahatchee and open water got suspicious when Krist claimed he had lost his registration paperwork.

He radioed back to other locks and learned the man had crossed the state using the same story at each stop.

He allowed him through but called authorities, and they quickly discerned that the suspicious boatman was Krist.

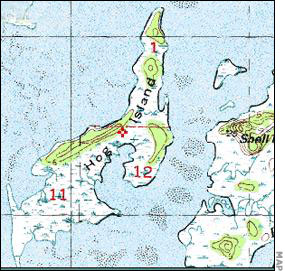

A helicopter was scrambled up and an armada of police boats was turned loose on the Caloosahatchee. With lawmen approaching from all directions, Krist beached his vessel on Hog Island, a 30-square-mile jungle of dense mangroves in the bay off Fort Myers.

Agents and officers surrounded the island, and Krist was finally tracked down after 12 hours of running through the jungle.

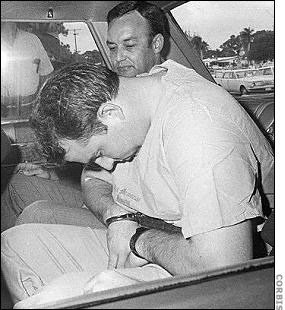

According to the deputies who arrested him, Krist’s first words were, “I have rights!”

The deputies recovered $17,000 from his pockets, and the FBI found another $480,000 in the boat.

Subtracting the cost of the boat, Krist had netted a grand total of $761 from the perfect crime.

Ruth Eisemann gained the distinction of becoming the first woman ever on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list.

But her stay there was brief.

Seventy-nine days after the kidnapping, the financially destitute woman was arrested after applying for a job as a carhop in Norman, Okla. She was hauled back to Georgia for trial.

The jury did not buy her excuse that she was blindly in love with the charismatic Krist. She was convicted and sentenced to seven years. She was paroled after four and promptly deported to her native Honduras. She remains persona non grata in the U.S.

Krist, meanwhile, seemed bored by the trialperhaps because his conviction was a foregone conclusion.

He had sought an insanity ruling, but the gambit failedeven after delivering one memorably egocentric statement after another to a court-appointed shrink.

He said, for example, “I am a superior human being.”

The prosecutor, Richard Bell, judged him a superior thug, and he aggressively sought the death penalty, allowed under Georgia law in kidnapping-for-ransom cases.

During a break one day, Krist told reporters he expected to get “the electric chair or whatever means these barbarian humans use these days, I suppose.”

The jury convicted him, and a majority voted for execution. But four jurors held out for a life sentence, so the panel was forced to recommend mercy.

Many believe Krist escaped death only because Barbara Mackle expressed appreciation during her testimony that Krist had spared her life by phoning the FBI after the ransom recovery.

Judge H.O. Hubert handed down a life sentence.

Krist said nothing. One reporter said he seemed to stifle a yawn and glance at the clock.

A prison shrink who evaluated Krist in 1969 called him “borderline schizophrenic.”

In one revealing anecdote, Krist refused to acknowledge that his kidnapping plan was anything short of brilliant.

After an hour of combative answers to questions about all the details that had gone wrong, he finally allowed that “my only mistake was a minor miscalculation” about the number of lawmen pursuing him on Hog Island.

“He seems to have an obsession for others to think of him as a superior individual,” the psychiatrist wrote. “He talked of his crime being part of a grand design which he had.”

Once in prison, Krist’s grand design centered on finding a way out.

First he tried groveling. In 1971, he wrote a letter to his victim: “Of course my crime was evil, immoral, and cruel and I cannot excuse it. I don’t deserve forgiveness but it would make me happy to receive it. The crime is past and I can learn from it but I cannot change it.”

He then tried propaganda. In 1972, he published a memoir, “Life,” an odd, 370-page account of his life that was equal parts egomaniacal jeremiad and heavy-breathing account of his sexual achievementsall written in a haughty, academic tone.

“I’m reconciled to pay my social bill,” he wrote. “And then maybe … I can go out and live, if not in perfect amity, then perhaps within a square-shooting truce that will lead to my repudiation of the hostile spirit down to its last vestige.”

He next tried escape, concealing himself inside a garbage truck. But he was caught and his privileges revoked.

Finally, he tried the perfect-prisoner con, and he found the perfect sucker.

Krist began tutoring fellow inmates, teaching them to read and write. He took college classes, trained as an EMT and worked in the prison hospital. He also cultivated a relationship with James T. (Tommy) Morris, the influential chairman of the Georgia Parole Board.

Under the lenient parole protocols of that era, even as a lifer, Krist became eligible to apply for parole after just seven years in prison.

He lined up a number of doctors and professors who lobbied for his release, led by his prison pen pal girlfriend, Joan Jones.

The decision to free or detain Krist was left to the parole board, and Morris had tremendous influence on his colleagues.

Morris advocated for Krist’s release as early as 1976. The convict promised to return to Pelican, Alaska, to work in the family shrimp business.

A hitch arose when Alaskan officials said they didn’t want him back.

But by 1979, after lobbying by Krist’s family and Tommy Morris, Alaska acquiesced. Barbara Mackle, by then a wife and mother, did not oppose the release. So the Georgia Parole Board quietly voted to free the infamous con.

Prosecutor Bell was incensed, predicting that Krist’s “devious mind” would inevitably lead him back to crime.Krist’s trial judge, H.O. Hubert said Morris had been conned.

“I just don’t think he will ever change,” said the judge.

But Morris continued to tout Krist’s rehabilitation, despite a public outcry.

“There is nothing in our files to indicate Gary Steven Krist is violent or dangerous,” he told the New York Times. “If he does commit a crime, it won’t be a crime of violence.”

Remarkably, Morris claimed the kidnapping was a negligible crime, because no one was killed.

“The fact is the victim did live and is totally recovered,” Morris said. Barbara Mackle “suffers no lasting trauma from the ordeal … Therefore the net result is little harm was done.”

“He isn’t the same person at all,” Krist’s mother, Bobbie, told the Times. “It just took him a long time to grow up. I think he has served his time and paid his debt to society.”

He walked out of prison on May 14, 1979, still just 33 years old. He told reporters that he might just become a missionary.

The wife he had abandoned divorced him while he was in prison. But waiting at the prison gates was Joan Jones, his prison pen pal.

They were married a few months later.

Krist’s mother predicted it would be a long time before America heard from her son again. This was true.

Krist began taking college classes in Alaska, with an eye toward pursuing what he called his “lifelong dream” of becoming a doctor.

Legitimate medical schools bar felons, so Krist began working a new con. He contacted his old pal Tommy Morris in Georgia to press for a pardon.

Morris squeezed a recommendation out of Krist’s probation officer, and soon Krist got his pardon, which allowed him to enroll at second-rate Caribbean medical schools.

He graduated in the mid-1990s, then apparently worked as a doctor in Haiti while desperately seeking positions back home.

But his past proved a heavy burden.

He tried medical residencies in West Virginia, Alabama and Connecticut, but lost the positions when his criminal background came to light.

In 2001, he took a position in Chrisney, Ind., a rural village with no doctor. Indiana was aware of his past and granted Krist a probationary license. But he lost that job, too, after the Evansville (Ind.) Courier-Press published a story about the Mackle kidnapping.

He told the paper, “I think a man should be judged as much by the last half of his life as by the first half.”

In 2003, after Indiana revoked Krist’s medical license, he told a reporter, “I’m not going to be able to fulfill my dream. I tried to be a beneficial part of society. They wouldn’t let me.”

“He made a strong effort to rehabilitate himself,” Fred Tieman, Krist’s lawyer, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “But it didn’t work out. The effort to become a doctor failed, he believes, because his history came back to haunt him.”

He was a victim forced, it would seem, to turn to turn to a new career: cocaine importation.

In the fall of 2001, at about the time he got his probationary medical license in Indiana, Krist and his wife’s son, Henry Jackson (Jackie) Greeson, incorporated Greeson & Krist Construction Inc. with the Georgia Secretary of State. The company claimed specialties in sheet metal fabrication and “bullet-proof rooms.”

They developed a secondary specialty, as well.

Gary Krist rented a 27-foot sailboat in Point Clear, Ala., just before Christmas 2004. Federal authorities believe he sailed to Cartagena, Colombia, where he bought a kilo of cocaine.

A year later, Krist and Greeson chartered another sailboat from a Mobile Bay marina from Nov. 14 to Dec. 4, 2005. The men again sailed to South America and bought six kilos of cocaine, about 13 pounds.

When they returned from that trip, the charter company grew suspicious when employees found aboard the boat a map of the Colombian coast.

The charter firm contacted authorities. When Krist reserved another sailboat for just a month later, in January 2006, federal agents installed a tracking bug on the vessel.

Krist again sailed to Colombia.

When he returned to Mobile Bay on March 6, an army of local, state and federal lawmen rushed the boat as it docked.

They seized four illegal alienstwo from Colombia, two from Ecuadorwho had paid Krist $6,000 each. And in a cooler they found 38 pounds of cocaine in paste form, with a street value of as much as $2 million.

Authorities believe he used profits from the sale of his earlier cocaine purchases to buy progressively larger amounts of the narcotic.

Dwight McDaniel, a federal immigration agent in Mobile, said Krist had rigged a clever quick release for the cocaine in case his boat was boarded at sea.

The cocaine cooler was filled with cement and lashed in place with a rope. McDaniel said it would have taken just seconds to cut the rope and slide the cooler overboard, where the evidence would have sunk.

“We would have never found it,” McDaniel said. “It was a very good setup … (by) a very smart man.”

On March 10, drug investigators searched Krist’s home, on Georgia Highway 324 just outside of Auburn, 35 miles east of Atlanta.

They made a stunning discovery when they pried open a concealed trap door in the floor of a small garden shed.

A ladder gave access to a submarine-style workshop built inside a metal cylinder measuring 27 1/2 feet long and 8 feet in diameter.

The laboratory had running water and electricity and was stocked with chemicals and containers used to convert the cocaine from paste to powder, which authorities believe Krist and Greeson then sold in Atlanta.

The lab also featured an escape routea tunnel nearly 20 yards long that snaked to the surface, terminating in a camouflaged 50-gallon barrel.

Neighbors had a wide range of opinions about Krist.

One told the Athens Banner-Herald that Krist was a know-it-all.

“He just knows everything,” he said. “He don’t talk good about nobody.”

Another said Krist was not shy about his criminal accomplishments, saying he bragged about the Mackle kidnapping.

Others had a different take.

“He was as nice a person as you could meet,” said Billy Parks, a city councilman and Krist’s former mailman. “He was very polite just a gentleman.”

And another neighbor told the Athens paper, “He was a pretty good ol’ boy. He never raised his voice or said anything vulgar to my children … I ain’t never heard him say a cuss word.”

Gary Krist’s kidnapping victim has had nothing to say about his latest arrest.

In 1971, she coauthored a memoir about her ordeal, “83 Hours Till Dawn.” She said in the book, “I wanted to tell it once completely and as honestly as I could, so that it will be behind me. I want to end it. I want to put it behind me. Once and for all, I want it to be over. Forever and ever.”

She hasn’t spoken publicly about it since.

“It’s not a part of our life at all,” her father, Robert Mackle, told The Miami Herald 10 years after the kidnapping. “Nobody will understand that it didn’t affect her.”

Barbara Mackle married her college sweetheart, Stewart Woodward, who became a successful accountant in Atlanta. The couple had two children, then moved some years ago to a seaside home in Vero Beach, Fla.

She has deflected all attempts by the media to talk about Krist, but their fates are forever intertwined.

She may have spared Krist’s life with her merciful testimony.

“I know that I did not want Krist to be executed,” she wrote in her memoir. “For one reason, it was he who called (the FBI to free her).”

And her attitude about his early parole and pardon left him free to commit his latest crimes.

In his memoir, Krist praised Barbara Mackle for the measured tones she used when testifying a tacit acknowledgement that she may have saved his life.

As Krist put it, “My victim has put me in her moral debt for life.”

Krist and Greeson pleaded guilty on May 16, 2006, in U.S. District Court in Mobile to conspiracy to import cocaine and smuggling aliens. Their sentences could range from 10 years to life on each count, in addition to fines of up to $4 million.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Deborah Griffin has postponed the sentencing three times because Krist is frantically trying to cooperate with federal authorities. He and Greeson are expected to testify against Antonio Bryan Joseph, accused of conspiring with the men to distribute the cocaine.

Krist and Greeson are now scheduled to be sentenced in January 2007.

Krist’s wife, Joan, told the Athens, Ga., newspaper, “He is a good man, and he had not done anything to anyone in years.”

She expressed no resentment toward her husband, even though he involved her son in a racket likely to get him sent away for at least a decade.

For his part, Krist will go to prison and attempt to cultivate helpful alliances. No doubt he’s already trying to figure out a way to get out. He has one thing going for him: His brain.

Books

- “83 Hours Till Dawn,” Gene Miller and Barbara Jane Mackle, Doubleday & Co., 1971

- “Life,” Gary Krist, The Olympia Press, 1972

News Articles

- “Woman Is Sought in Mackle Case,” UPI, Dec. 23, 1968

- “Making an Impact,” Time Magazine, Jan. 3, 1969

- “Parole of Kidnapper Angers Atlanta,” by Howell Raines, New York Times, May 14, 1979

- “South Florida’s Crimes of the Century Riveted the Nation,” by Edna Buchanan, Miami Herald, Sept. 15, 2002

- “Buried Alive,” by Rachel Sauer, Palm Beach Post, Jan. 11, 2004

- “Kidnapper Now a Smuggling Suspect,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 11, 2006

- “An ‘Evil’ Crime, Then Quiet Life Until Drug Bust,” by Todd Defeo, Athens (Ga.) Banner-Herald

- “Smuggler Facing Life With Plea,” by Todd Defeo, Athens (Ga.) Banner-Herald,

- Sentencing Delayed for Drug Smuggler,” by Todd Defeo, Athens (Ga.) Banner-Herald,