The Frank Sinatra, Jr. Kidnapping — The Snatch — Crime Library

Barry Keenan eased the Chevy Impala to a stop outside Harrah’s casino, just across the Nevada state line from Lake Tahoe, California.

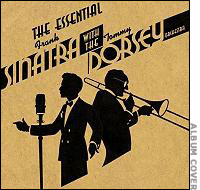

Squinting through a snow squall, he poked his pal Joe Amsler in the ribs and pointed to the illuminated marquee: “The Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, Featuring Frank Sinatra, Jr.”

A short time later, the two men found themselves standing outside Room 417 at Harrah’s Lodge. Keenan held a wine box — a prop filled not with Chianti but with pine cones.

Inside, Frank Sinatra, Jr., 19, was sitting in his under shorts and T-shirt, finishing up a room-service chicken dinner with John Foss, 26, a trumpet player in the Dorsey band.

They were due on stage at Harrah’s Tahoe Lounge for a 10 o’clock show — the sixth day of a three-week run there.

It was 9 p.m. on Sunday, Dec. 8, 1963, when Keenan raised his knuckles and knocked. The door was unlocked, and young Sinatra invited the visitor in.

“Hi, guys,” said Keenan. “I’ve got a package for you.”

Sinatra gestured toward the dresser and said, “Put it over there.”

Unburdened of the box, Keenan whipped out the revolver tucked in trousers and called out to Amsler, who stepped into the room brandishing his own pistol.

“Don’t make any noise, and nobody gets hurt,” Keenan snarled, trying to sound tough.

They bound Foss with masking tape and allowed Sinatra to don shoes, trousers and a coat — but no socks or proper shirt.

Soon Sinatra found himself sitting blindfolded in the Impala, which Keenan guided through a blizzard down the Sierra Nevadas toward a hideout house he had rented in Canoga Park, a Los Angeles suburb eight hours from Lake Tahoe.

The scheme was crazy on so many levels.

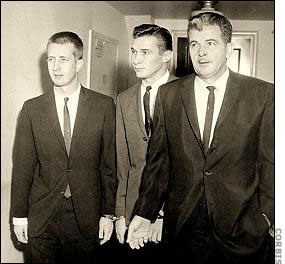

Keenan and Amsler, 23-year-old former high school classmates, were greenhorn criminals. It certainly was their first kidnapping.

Their victim, sitting in the backseat, was the namesake of the most famous entertainer in America. With ties to the highest echelons of both government and organized crime, Sinatra, Sr. could squash Keenan and Amsler like bugs.

So the kidnapping of Frank Sinatra Jr. was a half-baked act poorly executed by witless amateurs — and the second most infamous kidnapping in American history, after that of the Lindbergh Baby in 1932.

Inevitably, of course, it more or less worked.

Barry Keenan had always been a financial striver.

He grew up in L.A. and attended University High School — Uni High — which counts among its alumni Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Elizabeth Taylor, Ryan O’Neal, Jeff Bridges, James Brolin, David Cassidy, Sandra Dee, Roddy McDowall, Penelope Ann Miller and Randy Newman.

Keenan’s classmates included Jan Berry and Dean Torrence, of the surf-pop duo Jan and Dean, whose hits included “Surf City” and “The Little Old Lady from Pasadena.” Another school chum was Nancy Sinatra, eldest of the three Sinatra children.

Keenan’s parents divorced when he was a toddler. His father was a failed stockbroker who struggled with alcoholism. His mother battled depression.

Barry Keenan was determined to overcome his background and become wealthy like his famous classmates. He was obsessed with being a millionaire by his 30th birthday.

As he put it in a curious letter to his father before the Sinatra kidnapping, “Money has always been of the utmost importance to me.”

In fact, he tasted financial success as a very young man. He had been the youngest member ever of the Los Angeles Stock Exchange, and he had made money on real estate investments while still attending UCLA.

But then his young life turned. Keenan would later peg his downfall to a car accident in Westwood in 1961 that left him with chronic back pain that led to a Percodan addiction.

His physical problems were trumped by financial ruin brought on by the stock market crash in the spring of 1962 and a divorce that followed a brief marriage.

By the summer of 1963, Keenan’s bank accounts were depleted. So like a good Jaycee, he began to develop a business plan to recover his lost wealth.

“I started casting about for ways to solve my economic crisis, and I started thinking about ways to make money illegally,” Keenan told L.A. Weekly writer Peter Gilstrap in 1998. “I didn’t know how to deal dope, bank robbery didn’t make much sense, so I hit on the idea that you could raise a lot of money in a kidnapping.

“In my thinking and the way I would talk about it, it was like a stock offering… and I didn’t see it as a crime. Intellectually, I knew it was a crime, but emotionally I was working very hard to rationalize it, to make it an OK deal.”

He was brimming with enthusiasm by the time he paid a visit to his high school friend Dean Torrence.

He explained that he had a get-rich plan. All he needed was $5,000 in seed money to make it happen.

Torrence asked for details, and Keenan earnestly explained that he was planning “the perfect crime”: a celebrity kidnapping. He said he had considered snatching Bob Hope’s adopted son, Tony, before settling on Frank Sinatra, Jr.

“I decided upon Junior because Frank, Sr. was tough,” said Keenan, “and I knew Frank always got his way. It wouldn’t be morally wrong to put him through a few hours of grief worrying about his son.”

Keenan said the kidnapping would net him $100,000, which he would parlay into a million within 10 years through clever investment. He would then discreetly repay Sinatra the ransom.

If Torrence thought his friend was nuts, he didn’t say so at the time. He wouldn’t spring for $5,000, but he gave him $500.

And with a flush wallet, Keenan went about executing his business plan.

The Sinatra offspring could have warned Keenan that wealth wasn’t everything.

Frank, Sr. had married Nancy Barbato, his Hoboken, N.J., childhood sweetheart, in 1939, the year the crooner began to find fame as the “boy singer” of the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra.

Daughter Nancy was born in 1940, followed by Frank, Jr. in 1944. By the time daughter Tina arrived in 1948, Sinatra was out of the Dorsey band and avidly pursuing an acting career.

The family moved from New Jersey to Los Angeles, where in 1951 Sinatra left his wife for actress Ava Gardner. The two were married barely a week after his divorce from Nancy was final.

(The tempestuous Gardner relationship lasted less than two years. Sinatra also was married briefly to Mia Farrow. She was 21 and he 50 when they wed in 1966. Sinatra’s fourth and final marriage, in 1976 to Barbara Blakeley, ex-wife of Zeppo Marx, endured 22 years, until his death in 1998.)

Sinatra had a remote relationship with his children, who lived with their mother in a Bel-Air mansion.

As Frank Jr. told the Washington Post in 2006, “He was unreachable. He was traveling, or off making some movie… It was only on rare occasions when we saw each other.”

Frank Sinatra, Sr. was the king of all media by 1963.

“Sinatra-Basie,” his recording with the bandleader Count Basie, was a hit among the jazz set, and his pop recordings continued to dominate radio — at least among the stations that had not gone rock ‘n’ roll.

After nearly 20 years of film roles, he had finally gained critical praise for his work in The Manchurian Candidate. To boot, he hosted the Academy Awards on ABC television in 1963.

He had limitless fame and wealth. But more importantly, he had gained legitimacy. After years of whispers about mob connections, Sinatra had forged friendships with upstanding citizens, including President John Kennedy.

Young Sinatra did not follow sister Nancy to University High. Instead, he was sent away to boarding school, spending three isolated junior high years near Phoenix before settling in at the Desert Sun School, in the San Jacinto Mountain town of Idyllwild, California, an hour’s drive from Frank, Sr.’s home in Palm Springs.

Sinatra, Jr., an accomplished pianist and budding composer, enrolled at UCLA to study music, but a real-world education beckoned.

Young Sinatra’s first gig, in 1962, was at a Phoenix club owned by the family of a boarding school buddy. He spent the summer of 1963 working with an orchestra at Disneyland.

Elvis Presley and rock ‘n’ roll had hastened the demise of Big Band music. A few of the old dance bands were limping along as nostalgia acts, including the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra — even though the famed bandleader had died in 1956.

Dorsey

Sinatra, Jr. was invited to join the Dorsey band — no doubted aided by the unseen hand of his father.

He made his debut in April 1963 at the Royal Box nightclub, in the Americana Hotel in New York. His father sat beaming in the audience with restaurateur Toots Shor and actor Jackie Gleason, as Sinatra, Jr. sang “I’ll Never Smile Again,” the ballad that was Sinatra, Sr.’s first hit with the Dorsey band.

Junior sang in a baritone that had the same warmth of his father’s singing voice. And if he lacked the perfect phrasing, story-telling ability and stage presence of his dad, who didn’t?

Young Sinatra won praise from patrons and critics. As the New York Times put it, “He scored a hit as a singer and showman.”

With the Sinatra name providing new momentum, the Dorsey band was booked for a 36-week tour, including the three weeks at Harrah’s near Tahoe.

Junior put his college education on hold for the tour. It was a business decision. And Sinatra’s business plan jibed perfectly with Barry Keenan’s.

Keenan couldn’t execute his scheme alone, so he brought in two accomplices — Joe Amsler, his school buddy who was working as an underemployed abalone diver, and John Irwin, 42, a house painter.

Irwin had once dated Keenan’s mother.

In one of the more curious footnotes to the caper, Keenan would later reveal that he hired Irwin because he had a gruff voice. He was designated as the gang member who would phone Sinatra Sr. to demand a ransom. Knowing Sinatra’s pugnacious reputation, Keenan felt he needed someone who could exchange tough talk, like a Hoboken hoodlum.

He offered to pay Amsler and Irwin $100 a week for their services — far more than they were earning legitimately.

Using the name Frank Long and a phony English accent, Keenan rented a house in Canoga Park where Sinatra, Jr. could be held after the abduction.

Plan A was to grab Junior in October 1963 during an appearance of the Dorsey Orchestra at the Arizona State Fair in Phoenix. When that fell through, Keenan chose a new date for the kidnapping: Nov. 22, 1963, while the band was appearing at the Ambassador, the landmark Wilshire Boulevard hotel in L.A.

Plan B was aborted with the news of President Kennedy’s assassination that afternoon. The kidnap gang was too depressed to muster a felony.

This led to Plan C, the kidnapping in Lake Tahoe, which occurred in a near-blizzard.

“When Junior finished his engagement at the Ambassador Hotel, I found out he was playing in Nevada and then going to Europe, and I would lose him,” Keenan told L.A. Weekly. “It was do or die.”

By then, Keenan had run out of cash, including two $500 “seed money” loans from Dean Torrence.

Keenan managed to lease the Impala and buy enough gas to get to Tahoe. He and Amsler checked into a hotel, but they had to no way to pay, so they were not going to be able to check out.

“I think we had six cents between us,” Keenan said. “It became sort of like, now we had to kidnap Frank Sinatra, Jr. just to get out of the hotel. As crazy as that sounds, that’s what it boiled down to. I needed to get money from Junior because I didn’t have enough gas in the car to get to L.A.”

Sinatra was barely able to help. He had just $11 — just enough to get them back to the Canoga Park hideout. En route, they managed to talk their way through two roadblocks set up specifically to catch the Sinatra kidnappers.

Within ten minutes of the abduction, John Foss, the trumpet-playing eyewitness, had wiggled out of his bindings and alerted the orchestra road manager, Tino Barzie.

Soon a phalanx of 100 local and state cops and two dozen FBI agents were searching for the stolen Sinatra. (According to crime legend, Chicago mobster Sam Giancana offered his assistance, but Sinatra, Sr. declined.)

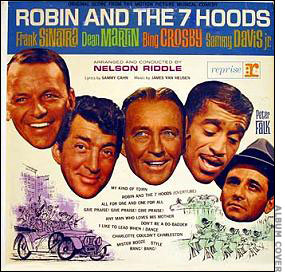

Frank, Sr., in the middle of shooting the forgettable Rat Pack musical Robin and the 7 Hoods, hurried to Lake Tahoe and set up headquarters at the Mapes Hotel in nearby Reno, Nev.

The high-strung Sinatra did not take it well.

“He has just been sitting and staring at the phone,” his press mouthpiece, Jim Mahoney, told reporters. “When it rings, he jumps. I had to practically force him to eat. He doesn’t think about eating. He just looks at the phone.”

The kidnappers would later say that they had an amicable relationship with Sinatra, Jr. until they asked for his father’s phone number.

He flatly refused.

“You can shoot me, beat me up, whatever,” he said. “I’m not giving you a phone number. I’m not scared of you guys.”

But Keenan happened to hear a radio news report that Sinatra was holed up at the Mapes in Reno, and Keenan made the first of seven phone calls to Sinatra, Sr. on Monday night, 22 hours after the abduction.

Sinatra is said to have impetuously offered $1 million for the safe return of his only son, but the kidnappers insisted they wanted only $240,000. That was Keenan’s business model, and he was sticking to it.

During a second call, the next morning, Frank, Jr. was allowed to say hello to his dad. In a third call, Sinatra was directed on a dry-run ransom drop to a gas station in Carson City, Nev., 30 miles from the kidnapping scene.

Authorities said the caller — Keenan, despite his plans to use tough-talking Irwin — was an educated young man who used firm and formal language, including the phrase, “Discretion will be the demeanor.”

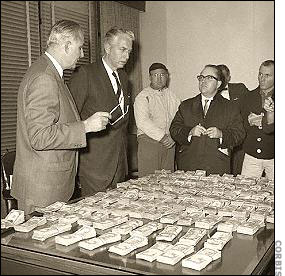

Sinatra, Sr. called on his friend Al Hart, president of City National Bank in Beverly Hills, to assemble the $240,000.

The bills were photographed by the FBI, then packed into an 18-inch square package that weighed 23 pounds — 12,400 bills in all, in denominations ranging from $5 to $100.

Keenan made several more calls to the Mapes, ordering Sinatra, Sr. to Los Angeles for the ransom drop. In a series of calls to pay phones, he finally directed a courier to leave the money between two school buses parked at a gas station on Sunset Boulevard.

FBI Agent Jerome Crowe made the drop just before 11 p.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 11, about 74 hours after the abduction.

Keenan and Amsler picked up the cash as the FBI discreetly filmed the proceedings from several vantage points.

Keenan returned to the hideout to discover that Irwin and Sinatra, Jr. were gone. Irwin had gotten edgy and decided to split. He drove the hostage onto the 405 freeway and let him out at the Mulholland Drive overpass.

Young Sinatra walked a few miles toward Bel-Air, then summoned a private security guard who happened to be passing by.

The guard, George Jones, drove Sinatra to his mother’s house, where both his parents were waiting.

As reporters watched, young Sinatra said, “I’m sorry, Dad.”

He father gave him a hug and replied, “You don’t have anything to be sorry for.”

Sinatra, Jr. told reporters he was “scared and a little bit nervous, naturally,” during the ordeal. But he said he was a cool cat compared with his abductors.

“By the way they talked,” he said, “I think they were even more afraid than I was.”

After grabbing the ransom, Keenan, Amsler and Irwin reveled in their new wealth.

“We laid all the money out, danced on it, lit cigarettes with it, did all the things we’d seen in the movies,” Keenan told L.A. Weekly. “We had a money war, throwing wads of bills at each other.”

But the fun didn’t last.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover claimed that brilliant gumshoe work by his agency brought the kidnappers to justice.

It wasn’t true.

L.A. cops, jealous that Hoover stole the limelight, revealed that the caper was solved by the most ordinary method: Somebody dropped a dime.

John Irwin split with his cut, $40,000. He planned to go to New Orleans and get lost, but he stopped in San Diego to see his brother.

The Sinatra ransom payment and safe return of Junior was a huge news story across America. John Irwin couldn’t help himself. He bragged to his brother about his role.

When John went to bed, his brother made a phone call. The jig was up.

Irwin was in custody within hours, and he quickly gave up Keenan and Amsler.

They had had a chance to spend just $6,114 of the ransom loot — most of it on a furniture set Keenan bought to impress his ex-wife.

The FBI planned to confiscate the furniture, but a magnanimous Sinatra, Sr. said, “Let the poor broad keep her couch!”

He also gave a $1,000 tip to the security guard who delivered Junior home. On the day after his son’s release — Dec. 12, Frank, Sr.’s 48th birthday — he treated a pack of pals to dinner and drinks at the Sands casino in Las Vegas.

He told his friends to bring no birthday gifts.

“Getting Frankie back is the best birthday present I could ever have,” Sinatra said.

Appropriately, the trial of the three men in federal court in Los Angeles just two months after the abduction was a circus-style spectacle, with defense attorney Gladys Towles Root serving as ringmaster.

The kidnapping seemed too bizarre to be true. And this became the primary defense, a strategy planned by John Irwin’s attorney, Gladys Towles Root.

The famously flamboyant Root was one of America’s first modern celebrity lawyers. Her firm juggled hundreds of criminal cases at a time, and Root became a specialist at defending men accused of sex crimes.

For 50 years, she was a courthouse fixture in southern California, rushing from one courtroom to another, often with reporters following in her slipstream.

Root enjoyed being the center of attention, and she certainly had the wardrobe for it. She wore hats that Carmen Miranda might have rejected as too gaudy. And in 1963, as her 58th birthday beckoned, she continued to pour herself into skin-tight dresses accessorized with enough oversized pins, brooches, bracelets and necklaces to fill a pawnshop jewelry case.

Root chose a well-worn strategy in the Sinatra defense, one that she often used in her sex crime cases: blame the victim.

She claimed the abduction was a publicity stunt to jumpstart Frank, Jr.’s career. She accused Junior of plotting his own kidnapping as “an advertising scheme” to both advance his career and to “make the ladies swoon like papa.”

Keenan played along by falsely claiming that he had been approached by a Sinatra intermediary.

Root elicited only scant evidence about the victim’s alleged willingness — for example, that Frank, Jr. shook hands with John Irwin at his release and said, “It’s too bad we couldn’t have met under different circumstances.”

But she grilled both Junior and Sinatra, Sr. on the witness so gratingly that each finally lost his temper.

Sinatra, Sr. was incensed. Stealing his son was one thing. Calling him a publicity hound was another.

In the press gallery, one wiseacre stage-whispered to another, “Do you think Sinatra will be acquitted?”

Root told the jury the case hinged upon “not who committed the crime, but whether a crime was committed.”

In the end, the defense failed.

All three defendants were convicted, and Judge William East lowered the boom. Keenan and Amsler got life plus 75 years, and Irwin got 16 years.

But the circus played on.

Under federal prison guidelines, Keenan qualified for a psychiatric evaluation, which was conducted in Missouri. The prison shrink set prosecutors to gnashing their teeth when he ruled that Keenan’s judgment was so clouded by Percodan addiction at the time of the abduction that he likely was insane.

Judge East was compelled to reduce the sentences of Amsler and Keenan to 24 years, and a picayune technicality further diminished their time.

As a result, under the liberal parole protocols of the 1960s, both Amsler and Irwin were released after just 3 ½ years. Keenan, the brains of the operation, walked free a year later.

Remarkably, Dean Torrence, the rock star who financed the kidnapping, escaped punishment.

Torrence told L.A. Weekly that he didn’t believe Keenan was really going to kidnap Sinatra, Jr.

“I don’t think I ever took him seriously,” Torrence said. “It was so insane.”

Forty years after he walked out of prison, Keenan is a lifetime removed from his federal felony, although he has nurtured his obsession with money. Right out of the joint, he got busy making his first million through real estate projects, including office and residential buildings, retirement homes and RV parks.

A recovering alcoholic and repeat-offender groom, Keenan helped develop Lake Whitney, south of Fort Worth, Texas, where he now lives, and is involved in other high-end residential projects.

In 1998, Keenan told the story of the kidnapping for the first time, to Gilstrap of L.A. Weekly. The long, comical account of the unlikely crime became the basis of a 2003 Showtime film, Stealing Sinatra, starring Ryan Browning, David Arquette and William H. Macy as the hapless kidnappers.

Keenan was to earn as much as $1.5 million for participating in the production, but Sinatra, Jr. successfully sued him under California’s Son of Sam Law to stop him from profiting from the film.

Keenan has said that one of his greatest regrets about the crime was the defense strategy to blame Sinatra, Jr.

He said it was the idea of defense attorney Root, who died in 1982 at age 77, after Keenan told her that Sinatra, Jr. was “very cooperative.”

Joe Amsler, meanwhile, had a brief career in motion pictures, acting as a stand-in and stunt double for actor Ryan O’Neal, another schoolmate, in such films as The Thief Who Came to Dinner and What’s Up, Doc?

He later worked as a ranch hand in California before retiring to Virginia with health problems. Amsler, 65, died of liver failure in Roanoke on May 6, 2006.

For more than 40 years now, Frank Sinatra, Jr. has lived with snickering insinuations about his role in the kidnapping. The defense strategy failed in court, but it continues to thrive in the court of public opinion.

Many people know nothing about the kidnapping — except that Sinatra, Jr. supposedly planned it himself.

The fallacy has framed the poor man’s life.

At age 63, Sinatra, Jr. still plugs along as a performer, singing his father’s songs at nostalgic casino shows. Among musicians, Sinatra Jr. is known as reserved, competent and a bit quirky.

He is an able performer, but he still lacks the stage presence of his famous father. Sinatra, Jr. is single. He was married — briefly — in 1998, and he has a college-age son, Mike, from an earlier relationship.

He gave a blunt assessment of his career in a 2006 interview with the Washington Post.

“I was never a success,” Sinatra, Jr. said. “Never had a hit movie or hit TV show or hit record.”

Perhaps that is because he has steadfastly insisted on making a type of music that hasn’t been popular for 50 years.

In 1957, as rock ‘n’ roll was transforming popular music, Sinatra, Sr. was quoted as saying, “Rock ‘n’ Roll is phony and false, and sung, written and played for the most part by cretinous goons.”

One of those cretinous goons turned out to be his daughter, Nancy.

She scored pop hits in the 1960s with “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’,” “Sugar Town,” “How Does That Grab You, Darlin'” and “Something Stupid,” the latter a duet with her father.

But Sinatra, Jr. has always stubbornly resisted the sorts of tunes that sell in the contemporary market. His performances are like time travel, with one Big Band standard after another — tunes like “I’ll Never Smile Again,” “Night and Day” and “I’ve Got the World on a String.”

He performs with a 38-piece orchestra — one of the few performers left who use so many live musicians rather than a synthesizer. (Even that is a downsized band. At shows in his latter years, Sinatra, Sr. always bemoaned the fact that he was the last entertainer to use a 68-piece orchestra.)

On many tunes, Sinatra, Jr.’s band plays the swinging arrangements written by Nelson Riddle for Sinatra, Sr. Junior conducted his father’s orchestra during the last decade of Sinatra’s, Sr.’s life, and he inherited his father’s sheet music library.

Sinatra, Jr.’s show is expensive to mount, and that “sticker shock” can make gigs hard to come by, Sinatra told the Post.

“I just had visions of doing the best quality of music,” he said. “Now there is a place for me because Frank Sinatra is dead. They want me to play the music. If it wasn’t for that, I wouldn’t be noticed… There is no demand for Frank Sinatra, Jr. records. There never has been. Rod Stewart is now doing the Great American Songbook. So is Harry Connick, Jr…. Well, Frank Sinatra, Jr. has been doing it for 44 years.”

“Frank Jr., the Unsung Sinatra,” by Wil Haygood, Washington Post, July 9, 2006

“The Man Who Stole Sinatra,” by Mike Allen, Roanoke Times, May 18, 2006

“Snatching Sinatra,” by Peter Gilstrap, L.A. Weekly, January 1998

“Obituary: Gladys Towles Root,” Los Angeles Times, Dec. 23, 1982

“Terms Reduced in Sinatra Case,” New York Times, July 8, 1964

“2 in Sinatra Case Given Life Terms,” by Gladwin Hill, New York Times, March 8, 1964

“Defense Sees a Publicity Stunt in Sinatra Kidnapping Case,” by Bill Becker, New York Times, Feb. 12, 1964.

“Police Chief Is Critical of FBI in Solving of Sinatra Kidnap Case,” by Bill Becker, New York Times, Dec. 21, 1963

“Police See Amateurish Work in Kidnapping,” by Gladwin Hill, New York Times, Dec. 16, 1963

“Sinatra Jr. Freed Unhurt; $240,000 Paid by Father,” by Gladwin Hill, New York Times, Dec. 12, 1963

“Frank Sinatra Jr. Reported Abducted,” New York Times, Dec. 9, 1963