Adam Worth: The World in his Pocket — Unlike a Hero — Crime Library

Adam Worth: The World in his Pocket

Unlike a Hero

“The more things a man is ashamed of, the more respectable he is.”

— George Bernard Shaw

The words refined and gaudy, by all practical standards, contrast. But, somewhere between the ether of the two words there is a fine line that, when the words blend across that line, a rarity is created. This specimen is one of color but with an ability to control that color to his/her advantage; to sip of the grapes of life with a celebratory vigor and vim and always emanate what the Parisians call en elegance.

Adam Worth steered between the earthiness of the lowlife and the headiness of the lavish high society crowd with such ease that he, at times, didn’t seem to merely live life, but manipulate it. Much of his actions were more instinctive than by design; he followed his desires. For one, he was neither a parasite nor a hypocrite, but enjoyed the beneficence offered by his company in sunlight and in shadow. In Victorian London, he could command a troop of Fagin-like pickpockets before sunrise, then discuss the qualities of imported silks over domestic weave in the gentlemen’s clubs at noon.

He knew the poor and he felt comfortable with, and enjoyed, their camaraderie; but he also relished the architecture of the wealthy frame of mind and, yes, enjoyed their camaraderie a little more.

Adam Worth was a thief. He stole cash, he stole jewels, he stole women’s hearts and he stole a priceless work of art. Of the women he loved most in his life, one was a duchess, albeit only on canvas. She was the Lady Georgiana Spencer, a controversial figure of uninhibited womanhood, and ancestor of the 20th Century’s remarkable Princess Diana.

at his height

(Pinkerton’s, Inc.)

Because of his combined knowledge of the streets and his aptitude to recognize arte d’clasique — and most of all because of his ingenuity – Adam Worth became what the world-famous Pinkerton Detective Agency called “the most remarkable criminal of them all”. Scotland Yard commissioned him “the Napoleon of Crime” and mystery writer Arthur Conan Doyle used him as a model for the fictional consummate of evil, Professor Moriarty in his Sherlock Holmes stories. But, Adam Worth was not “a villain of the lowest degree,” to employ a piece of literary light from the Victorian Melodrama. Worth never harmed anyone’s person, never threatened a life with knife or gun; he robbed only those whom he considered rich enough to lose money; he stole fortunes and he lost fortunes. He gave thousands of British pounds and French francs and American dollars to friends who were on the skid and he never asked to be repaid – all he asked was loyalty.

He performed honest jobs for probably only a few months in his life – and became one of the wealthiest and most respected men in Europe.

* * * * *

Despite later rumors that he was the son and heir of wealthy aristocrats – perhaps of royal English birth – Adam Worth was born to rag-poor German-Jew parents in Germany in 1844. When he was five years old, the family sailed to America where the elder Herr Worth (probably Werth, or perhaps Wirtz) set up a tiny tailor shop in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The father toiled, used his talents with needle and thread, and sewed up enough money to barely feed a wife and, eventually, three children; another boy, John, followed Adam, and then a daughter, Harriet.

He grew up in the area of the city that only dreamed of the “mighty Massachusetts rich”. His playmates were children from families like his own, sons and daughters of the sweating lower class, German Jews all, whose parents slaved in the mills, the factories and the backrooms of the garment shops; whose culture was left alone and unrecognized by upper-crust Protestant Cambridge. The children, faced with the obvious demarcation between Anglo-Americanism and their own reputation as “stupid immigrant Yiddish,” learned early the value of that mystical American thing called a dollar. Of how possessing many of them would remove them from their lowly status. The ways and means of getting ahold of one were often crooked, but, often, for them, the only way.

Into adulthood, Adam Worth would relate the foundation of his criminal career. A schoolmate told him, then a naïve boy, that he would trade him a new, shiny penny for two older, duller ones. Impressed by the sheen of the recently minted coin, little Adam accepted and ran home to show his father the great bargain he had made. Herr Worth erupted at his son’s lack of wit and chastised the boy for the fool’s play.

“From that moment on,” Worth would say, “I never again let anyone take the advantage over me.”

Worth was growing into a fine looking boy of dark hair and eyes; his once-open expression of hope had chiseled into a wiser one. His aquiline nose seemed to be always sniffing life’s experiences, inhaling and imbedding what his eyes saw into his brain, recording it to memory. Wandering through Cambridge, he would watch with keen interest the behaviors and the fine clothing and conveyances of the students from Boston who passed into and out of the gargoyle-crowned doors of Harvard University.

“In the Harvard students who paraded through Cambridge, the immigrant Jewish urchin had ample opportunity to observe the outward shows of wealth and privilege,” writes Ben Macintyre in his book on Adam Worth entitled The Napoleon of Crime. “Ashamed of his lowly origins, frustrated by impecunity, the young Worth clearly felt himself to be the equal of the fine young gentlemen strutting Boston Commons. Their wealth and sophistication provoked ambivalent feelings of envy, resentment and anger, and also of admiration and desire. Worth resolved to ‘better’ himself.”

At the age of 14, Adam Worth ran away from home to find his portal into society.

He drifted around Boston for a time with no apparent direction, then in 1860 strayed to New York City, which to a boy his age and in his stature must have gleamed as Utopia. Inspired to a new ambition at the site of the Goliath, of promised gold, the by-then 16-year-old Worth took what Macintyre calls “his first and only honest job,” that of a clerk in a department store. He remained in this position only one month.

That staying at this job longer might have led to a different future for Worth is an intriguing, but superfluous, proposition. Fuming over what they felt were limited states’ rights and the right to practice their beloved institution of slavery, Southerners ceded from the Union, and President Abraham Lincoln sent millions of armed troops below the Mason-Dixon line to squelch the rebellion. Civil war had come to America. With the first blast of insurgent cannons, the North summoned all grown males to answer her country’s call for restoration. Young Worth responded, not so much for a sense of patriotism, but for the yearning of adventure. And pay. Enlisting, he was guaranteed an attractive bounty of $1,000.

Adam Worth

(Matthew Brady collection)

Signing up on November 28, 1861, he lied about his age (recording it as 21, not 17), then marched off to boot camp along with other raw recruits of the 34th Light Artillery out of Flushing, New York. After a month of drilling on Long Island, the regiment headed south to converge with the Grand Army of the Potomac under General Pope. Evidently, Worth proved to be eager and able; his captain, the erstwhile Jacob Roemer, quickly promoted him to corporal, then to sergeant in a span of several months. Worth found himself in charge over a cannon battery.

The 34th New York repeatedly skirmished with General Robert E. Lee’s forces of Northern Virginia in the hills below Washington, D.C. Worth’s cannoneers distinguished themselves in the face of the enemy. In August, 1862, the Northern blues and Confederate grays clashed head-on, hand-to-hand, bayonet-to-bayonet, in what was to be one of the fiercest engagements of the Civil War — Manassas Junction, also known as Bull Run. “Bullets, shot and shell fell like hail in a heavy rain storm,” wrote Captain Roemer, “Men were tumbling, horses were falling and it certainly looked as though ‘de kingdom was a-comin’.'”

Certainly, the kingdom tapped Worth’s shoulder and, in doing so, played him a fortuitous trick. Rebel shrapnel felled him, not severely, and along with thousands of other stricken comrade, he was shipped off to Georgetown Hospital in the suburbs of Washington. While recuperating, he learned that back on the battlefield he had been accidentally listed as dead. This time, he would not be the recipient of a shiny new penny. This time, he would master the ruse and take the extra cent where a cent could be made. The army be damned, he literally walked out of convalescence a free man, free of all obligations to Captain Roemer and the New York 34th, free from the cause of liberty, and free from all but his own goal: to get rich.

He contrived to start bankrolling himself immediately. “Over the coming months, Worth established a system,” pens Macintyre, “(to) enlist in one regiment under an assumed name, collect whatever bounty was being offered, and then promptly desert.” But, author and researchist Macintyre is quick to point out that, despite these forsakings, Worth was not a coward, his design being financial not timid: “He repeatedly found himself in the thick of battle, including the Battle of the Wilderness in May, 1864, an engagement scarcely less ferocious than Bull Run.” Considering that Worth detested violence, and remained armed throughout several conflicts, is a testimony to his loyalty, a trait that was to become more apparent in his business dealings as the years passed.

the Scourge of runaway

soldiers (Ben Macintyre)

His chosen occupation was, despite its monetary virtues, an unsafe one. The Pinkerton Detective Agency, which was charged with nabbing runaways, had gotten wise to men like Worth who, in many creative ways, were partaking of the war’s spoils. Agents were fast closing in and Worth, remaining a step ahead, had effected several narrow escapes.

Quitting this enterprise, he fled to New York City where general sentiment was one of anti-war anyway. (In late 1864, a large portion of the city was burned to the ground when an intense weekend of draft rioting got out of hand.) By the time he reached the gotham, General Lee had surrendered and the war was over.

The Union was preserved, but Adam Worth’s private fight was only beginning. He determined to prove that a German Jew from the slums of Cambridge could reach the pinnacle. Glory, glory hallelujah.

Adam Worth: The World in his Pocket

Marm Mandelbaum

“A friend is, as it were, a second self.”

— Cicero

New York City in the mid-1860s was one of the most corrupt metropolises on earth. Its politicians were bribed, its constabulary paid off, and thieves, pickpockets, whores, gamblers and anyone else wanting life easy and fat and rich were prime clients. Graft was accepted procedure and the golden key to finer clothing, tastier food and higher social standing. Crime raged and those who controlled it, many of the politicians and police chiefs, zealously fed it. Scandal spread its Vulcan wings. Lawmakers gasped on the surface, and condemned it on the surface. Then laughed about it when the lights dimmed.

One aghast minister in 1866 estimated that the city’s all-told population of 800,000 included “30,000 thieves, 20,000 prostitutes, 3,000 drinking houses and a further 2,000 houses dedicated to gambling.” To illustrate the whimsical attitude toward vice, note the names of some of the more popular aforementioned drinking houses: Suicide Hall, The Morgue, Hell’s Gate, Cripples’ Home, Tub of Blood, and Inferno. Aliases having taken the place of their real names, the denizens of these gin mills bore their monikers like a medal. In any one of these dens of infamy on any night would be spotted characters like Pig Donovan, Eat-em-up Jack McManus, Gyp the Blood, Eddie the Plague and Baboon Dooley. Not outdone, the female consorts of these thugs took on, with relish, names like Red-Light Lizzie, Hell Cat Maggie and Jane the Grabber.

(Photo provided courtesy of Walter

& Naomi Rosenblum)

Within the underworld community, the city was fairly well divided by gangs within whose ranks were murderers, leg-breakers, confidence men, faro and keno dealers, black-marketeers, pickpockets, thieves, white slavers and trollops, paid according to individual prestige and talent, as well as the size and affluence of the gang to which they belonged. Gang titles were as colorful as their membership; among the hundreds were the Whyos, the Plug-Uglies, the Bowery Boys, the Roach Guard, the Forty Thieves and the Slaughter Housers.

It was into this off-balanced, though animated world that Adam Worth returned after the war, his sights set on conquering New York’s affluent Tenderloin District. Although neither a drinker nor a better, he hung in the low-ceilinged, gas-lit saloons to familiarize himself with and connect to the “employers” who were always on the scout for recruits. Since no one knew this 21-year-old boy, and he had to prove his prowess, he had to start low; the entry position into any gang was usually that of “dipper” or “pickpocket”. Sophie Lyons, a well-known woman extortionist and thief who liked the fresh learner, recalled in later years, “(Adam Worth) first tried picking pockets. He had good teachers and was an apt pupil. His long, slender fingers were just made for the delicate task of slipping watches out of men’s pockets and purses out of women’s handbags.”

Unlike most of his peers, Worth didn’t drink nor fornicate away the money he earned, but saved thriftily. A man of brain, not of brawn, he avoided the places of limelight and the trouble that often followed within their premises when the sun went down. “Of the 68,000 people arrested in New York in 1865, 53,000 were charged with crimes of violence. Yet Worth made it a rule that force should not play a part in any enterprise that involved him,” notes Ben Macintyre, author of The Napoleon of Crime. “Crooks who drank or fought would make mistakes, and for that reason he steered clear of the established gangs, which were often little more than roving bands of pickled hoodlums at war with each other.”

(Ben Macintyre)

It wasn’t long before Worth started his own little band of pickpockets and thieves, and quickly gained the trust of the major fences in town who pawned off the stolen materials he provided. He served as planner, employer and financier of heists throughout New York, concentrating his efforts in Manhattan. He took active part in only the more important jobs. What was supposed to be one of the more lucrative grabs, however, went astray when he was caught red-handed stealing a cash box off an Adams Express wagon. Unable to procure judicial favors – that benefit would come later – he was tried and sentenced to three years at hard labor in New York state’s dreaded Sing Sing Prison.

But, after a few weeks of prison life, Worth absconded. Night fell and he managed to slip between a corps of guards, slide over a rampart and swim the Hudson River to a passing tugboat. Soon, he was back where he left off. To conceal a face the law might be looking for, he grew a mustache and a set of sporty mutton-chop sideburns. The end result was a more dapper, more prosperous-looking Adam Worth. A successful image, he realized in the offing, was a good beginning.

Tired of trying to exist as a freelance crook, and not wanting to risk another arrest, he sought the patronage of one of several crime lords who controlled the police. Worth found his upholder in female form bearing the name Marm Mandelbaum.

Fredericka Mandelbaum – known as “Mom” or “Marm” by the criminals she harbored – was, according to laudits in early newspapers, “the greatest crime promoter of all time” and “the most successful fence in the history of New York”. Black eyed, corpulent and homely as sin, Marm was also the most beloved lady to grace the era of criminale personae. Operating out of a haberdasher’s store that she and her late husband Wolfe had opened as a cover in the Kleine Deutschland district, Marm financed the operations of a range of top thieves – only the best – by underwriting their enterprises and fencing their plunder. She took her percentage off the top, but was generous to her corps of professionals who did the dirty work.

If, perchance, her fraternity fell afoul of the law, she was always here to help them without a hitch. From the estimated $10,000,000 worth of stolen goods she managed each year, she could easily buy the police and politicians. Handling the payoffs were her two brilliant and crooked lawyers, William Howe and Abraham Hummel. And if a case ever made its way all the way to court, a rare thing, these two shysters could find loopholes in loopholes.

Professionals from the all levels of the criminal school paid homage to Marm. Nay, they worshipped her. Because she never acted the goddess nor demanded adulation – only loyalty – she was everthemore a woman deserving of allegiance. Behind her rough exterior was a lady of refinement, entertaining regally in her living quarters over the haberdashery. She doled out sumptuous feasts under iridescent chandelier and held balls under moonlight. Attendees included the nation’s most successful underworld figures – as well as lawmakers on the take, and celebrities. Her salon brimmed with furniture and trappings stolen from the city’s mansions and best hotels.

At her banquet table sat the cream of the underworld regime, from both sexes, as well as a score of judges, lawyers and policeman who drifted through Marm’s back door in masquerade. Usually on hand, dressed in high-society attire, were the likes of “Shang” Draper and “Western George” Leslie, two of the most cunning bandits in New York; glamorous jewel thief “Black Lena” Kleinschmidt; German-born, international burglar and safecracker Max Shinburn, who wore expensive derbies and called himself “The Baron” ever since buying a title of royalty in Monaco; and “Piano Charley” Bullard, a combination of misused talents — former butcher who now cut only into the tenderloins of bank safes, a trained pianist whose nimble fingers could tumble a safe as easily as they could play Chopin’s Etudes. His one fault was that he drank too much, but even inebriated, it was said, his digits never failed him, either in profession or in leisure.

It didn’t take Adam Worth long to ingratiate himself with these rascals and chanteuses of the night.

“In a profession not noted for its generosity,” says Ben Macintyre, “Marm was an exception (promoting many) who might need a helping hand up the criminal ladder.” One of these was Adam Worth. Legend claims she met him at one of her lavish soirees, he being an escort to a lady of dubious profession. She found in him a sincerity lacked by the others and in their initial dialogue probably noted a reflection of her own younger self. Both were of the same neo-classic ilk, both avoided violence, both believed in brainpower, both chased the finer material things in life, both sought refinement. Worth became a frequent visitor to Mandelbaum’s Haberdashery.

Macintyre muses: “An avid pupil, Worth appears to have found in Marm Mandelbaum an ally and a role model. The easy way she farmed out criminal work to others, her lavish apartments and social graces, were precisely the sort of things he had in mind for himself. Above all, it was perhaps Marm who taught the lessons that being a ‘perfect gentleman’ and complete crook were not only perfectly compatible but thoroughly rewarding.”

Under her tutelage and under the apprenticeship of her master disciples, Worth spent the year 1866 moving away from the soil of the streets and the cheap-shot little jobs they offered into the larger avenues of bank and store robbery, the paths he wished to follow. But, unlike so many of even the skilled thieves who became sculptures really fashioned by the hands of other craftsmen, Worth was fast becoming an artist unto himself. His teachers noticed his creativity, his discontent with normal procedures, his drive to improve old-fashioned methods to grab the plunder more easily and safer for all involved. And they observed his quick wit, his elan, his 24-hour-a-day, untiring, never- satiated obsession for total success. Marm Mandelbaum was proud of him.

Eventually, Worth graduated to higher things, performing jobs for Marm directly or merely practicing his learned skills for his own enterprise within and outside of New York City. For a time, he employed his brother, John, whom he found inept of criminal smarts and was, therefore, glad when the latter decided to return to a more mundane profession. Throughout the latter half of the 1860s, Worth architected several dozen after-hours robberies, emptying bank’s vaults and lightening jewelry counters of their stones. On a visit to his hometown of Cambridge, Massachusetts, he lifted $20,000 worth of bonds from an insurance company.

(Pinkerton’s, Inc.)

He enjoyed living on the edge. Once, when slipping through the front door of a Boston jewelry shop after a robbery, his pockets bulging with precious gems, he found himself face to face with the local beat patrolman. Without a blink, he smiled, saluted the officer and went about the business of a store owner locking up his own shop for the night – exchanging pleasantries with the policeman the entire time.

When Piano Charley Bullard got himself arrested by the Pinkerton Detectives after helping himself to a $100,000 shipment from the Hudson River Railway Express on May 4, 1869, Marm missed his piano concerts which would routinely accompany her parties. She summoned the two men who, if anyone could, could get Piano Charley out of White Plains (New York) Jail where he was awaiting trial. They were Adam Worth and “The Baron” Shinburn.

Marm wasn’t disappointed. Correspondences were secreted between the inmate and his rescuers, a tunnel was quickly dug under a jailhouse wall, and, at rendezvous, Bullard, grinning and chuckling, ran into the embrace of his two comrades in the very shadows of the slammer. Sentries on the wall, either paid off or extremely incompetent, missed the whole play.

Worth and Bullard became staunch friends from that moment and decided to go into business together. While there was no outward sign of contention between them and “Baron” Shinburn, they didn’t invite him to come along – simply, they didn’t like him; he was, despite his aristocratic dreams, loud, a braggart and dealt a better-than-thou attitude so crisply. Whether this caused a resentment no one knows, but Shinburn would spend the remainder of his life trying to outdo – but never exceeding – the successes of Adam Worth.

The new team of Worth-Bullard went straight to work. They chose Boston as their first “hit” since it was wise to remain aloof of New York where the law was scouring for its escaped prisoner. On the corner of Boylston and Washington streets stood the imposing columns of the Boylston National Bank, an edifice Worth remembered from childhood and a landmark in contrast to his moneyless childhood. Worth was not a vindictive man, but when he robbed that bank he did so with more than his usual touch of emotion – not with revenge against a prejudiced youth, but with a reassurance that his time was, finally, coming. The Boylston Bank job was Worth’s crowning achievement to date.

And it was ingenious. “Posing as William A. Judson & Co., dealers in health tonics, the partners rented the building adjacent to the bank and erected a partition across the window on which were displayed some two hundred bottles, containing, according to the labels mucilaged thereon, quantities of ‘Gray’s Oriental Tonic,'” explains Macintyre. “Quite what was in Gray’s Oriental Tonic has never been revealed, since not a single bottle was ever sold…After carefully calculating the point where the shop wall joined the bank’s steel safe, the robbers began digging. (They) piled the debris into the back of the shop, until finally the lining of the vault lay exposed.”

After the bank closed on Saturday, November 20, 1869, the final operation commenced. Inch-thick bits bore a succession of holes drilled side by side until a circle – large enough through which a man might crawl — was created. Hammers, wrenches and jimmies completed the task, prying the cut-out section off the vault. Worth wiggled through the opening and, by candlelight over the next few hours, undisturbed, handed to Bullard one million dollars in cash and securities. Not long after dawn Sunday, the thieves had already deposited their loot in steamer trunks and had shipped off with them to New York.

Boston was shocked at the crime, but praised the criminals’ boldness and cleverness. The Boston Globe went so far as to hint admiration at the thieves “of no ordinary ability”. But, the board of bankers was less impressed and called in the national Pinkerton Detective Agency to run down the crooks. Begun by Scottish-born Allan J. Pinkerton during the Civil War, these detectives were, according to Alan Axelrod in The War Between the Spies, “the world’s first ‘private eyes’…that served as the historical model for what in time would become the Federal Bureau of Investigation.”

head of Pinkertons in

New York

(Ben Macintyre)

It didn’t take long for Pinkerton operatives to track the shipment of trunks from the bogus storefront to New York through the steerage company that handled the cargo. Worth didn’t want Marm involved because he knew the property he held was too hot, and that the Pinkertons were known for hanging on suspects relentlessly. Marm could not afford detectives hovering over her place of business day and night. Rumor mill among the New York underworld was that Worth had been the one who invaded the Boylston Bank, and investigators were giving everyone the third degree; it was only a matter of time, Worth figured, before someone would crack under pressure.

There was one recourse. Handing the security bonds to lawyers Hummel and Howe to dispose of through underground financiers, Worth and his musical buddy grabbed the S.S. Indiana bound for Europe.

Adam Worth: The World in his Pocket

Kitty Flynn

“…Her eyes, they shone like diamonds, you’d think she was queen of the land, and her hair hung over her shoulders, drawn back with a black leather band.”

— Black Leather Band (Anonymous)

In the early months of 1870, two Americans named Charles H. Wells and Henry Judson Raymond, valises in hand, sauntered into the Washington Hotel in Liverpool, England. They asked for the best rooms in the inn, where they quickly changed from their traveling capes into the height of fashion, then together headed for the hotel bar. Wells was a Texas oil man, Raymond a financier from the East Coast. They ventured to the United Kingdom for a mix of business and pleasure.

Wells was, in reality, Bullard; Raymond was Worth.

While toddling around Liverpool over the next few weeks, they made it a habit to end their days in the hotel bar where they had both lost their hearts to a barmaid, one 17-year-old Kitty Flynn, an Irish colleen with thick blonde ringlets, dimples, plumpness in the right places, and silver-blue eyes as big as Erin’s moon – and just as lusty. Her orbs twinkled with a restless ambition that, when focused on a man, sent him into a dither.

Katherine Louise Flynn had fled the dull chores of her family’s Dublin farm at fifteen to see the world and get rich in it. Like Adam Worth had in Cambridge, she had spent her youth gawking at the rich in their carriages, the lords in their fine cutaway coats and the ladies in their swishing gowns and laced bonnets. Then, she scowl at her own palms, callused and beet-red from pushing the Flynn plow. The experience filled her with a yearning for the better life; if Adam Worth noticed in her the traits of an opportunist, he understood fully.

Both Americans wooed her with languish. It wasn’t long before she learned there true identities, truths that came spilling out under the allure of her fragrance in the misty seaside moonlight. Discovering that they were really not a rich oil man and financier made no difference to her; they were rich crooks on the lam from the United States and that was all the difference. The keyword was rich, after all.

(Katherine Sanford)

Pursuing the same girl did not hurt the two men’s friendship; it became a game of Best Man Wins. Kitty enjoyed both their company and, frankly, gave herself to both. She awed at Worth’s gentle soul, love for the classics and brilliance. Yet, she enjoyed Piano Charley’s more grab’em and kiss’em approach, too, which emerged more fluently with each drop of the porter he loved. Their woman eventually chose the proposal of Bullard, a fellow who had spent more time than Worth chasing ladies in America and therefore knew what it took to win them. In the years to come, as the boys and Kitty remained staunch friends and partners in crime, the Irish bride was not averse to, every now and then, after the hard-drinking Bullard passed out for the night, allowing Worth’s hands to creep inside her bustle. Again, that game of Best Man Wins.

While Kitty and Bullard honeymooned, Worth avoided the company of the Washington Bar, less festive without his friends, and decided to find new adventure, the kind that pumped his blood. He broke into a large pawnbroker’s shop during the quietude of a cold April night in Liverpool. He made off with £25,000, dividing it with Bullard and Kitty upon their return home – a belated wedding present. Throughout the year, other pawnbrokers were robbed by night until the two gangsters and their inamorata tired of the town. They sought bigger challenges.

Paris brought promises.

Still reeling from devastating war with Russia and a series of political upheavals,which included the bloody Siege of Paris, the city police paid little attention to the arrival of the Liverpool trio in June, 1871. The counterculture movement called Le Commune (The Commune) had been crushed only a month before and the conservative government once again held power. By the time that Mr. Raymond and the Wells couple set foot on French soil, the central police force, called the Paris Surete, had tunnel vision; they focused only on tracking down and annihilating the members of the now-defunct rebel government and barely glanced at the telegrams from America and England that warned them to keep an eye out for suspicious foreigners who may have robbed a bank in Cambridge, Massachusetts, or pillaged British pawn shops.

Paris lay in shambles from its political warfare, but its ancient streets looked classical to Adam Worth. He wandered through the “City of Lights,” along the River Seine, beneath the Arc de Triomphe, strolled from the spaciousness of the Champs de Elysees to the narrow cafes of Chaillot; he marveled at the ages-old and exquisite Cathedral Notre Dame, the Olympic proportions of Versailles, the ornate décor of the Place de Vosges, and he gasped at the beauty of the masterpieces in the Louvre.

(Travel Library/Philip

Enticknap)

With the remnants of the Boylston Bank job, Worth and Bullard (still wearing the names Raymond and Wells) bought an abandoned three-story building at Number 2, Rue Scribe, near the Paris Opera House, and turned it into one of the most attractive, and popular, social spots in town. Called the American Bar, it offered both legal and illegal entertainment for the citizens of Paris. On the second story was a spacious, posh lodging catering food and drink and private rooms where a client could host special feasts for his lady or for business partners, or celebrate weddings, anniversaries or birthdays; bartenders were imported from the United States to introduce (at least for Paris) novel drink concoctions; the chefs, however, were French gourmets. Newspapers and magazines from across America, from which guests could read the latest headlines abroad, lined kiosks and mahogany shelves in the anterooms, comfortable reading chairs provided for their browsing. Elegant light fixtures, mirrors, antiques and oil collections from Paris’ featured artistes lined the gleaming paneled walls. Carpeting lay inches thick; it was bordered in fringe.

Upstairs, on the third floor, the trio presided over a lush full-scale gambling house, complete with roulette, baccarat and an open bar that operated 24 hours. Kitty (Mrs. Wells) became its popular hostess in cherubic shape, decollete gown and necklaces of opals, or emeralds, rubies or sapphires. Piano Charley, suited in tails, sat center floor at a grand piano and played a mix of classic, foreign and popular tunes. Worth merely made himself available as greeter, making it his custom to ensure Paris’ (and the underworld’s) jauntiest high-rollers were treated royally. Because the salon ran against French law, a central buzzer mechanism could be sounded by the Maitre’d on the second floor to warn the inhabitants above of a possible raid. If sounded, the roulette wheels and the gaming tables would fold and disappear into an elaborately designed series of hideaways inside the walls and beneath the floors. Stupefied gendarmes, upon entering, would encounter nothing more than an airy café where gentlemen and ladies congregated, glass in hand, merely to trade repartee, listen to music, waltz, play innocent card games and parade in couture fashions.

Visitors to the American Bar consisted of those inside and outside of the law. On one particular night, Worth was startled to learn that among his guests were a number of merchants from none other than the Boylston National Bank, Cambridge. They stopped the proprietor, Mr. Raymond, to introduce themselves and their wives, and to congratulate him on the most wonderful cuisine and furnishings. Worth bowed, heartily thanked them for their patronage, and chuckled as he watched them leave never knowing that they had been the principle funders of the place.

Many of the world’s most charming rakes, rascals and felons crossed the threshold of the American Bar; from this assemblage, Worth oftentimes peopled his latest robberies and drew up a personal who’s who of people to know for future assignments. As a whole, they represented, under Worth’s captaincy, what Ben Macintyre in The Napoleon of Crime calls “one of the most efficient and disciplined gangs in history”. Baron Shinburn, who had deserted the clutches of an American law, was a nightly patron; so was lady thief Sophie Lyons who liked to “bum” with Europe’s elite d’corps. Other faces whom Worth had worked with in the past (welcoming them into his lair upon their appearance in the gilded confines of his club) were Eddie Guerin, an eager and amiable crook who later wrote his memoirs; Charles “Scratch” Becker, a Dutch forger so clever that he often fooled himself when trying to discern the authentic from his own reproduction; Joseph Chapman, long-faced, long-bearded and successful bank robber whose wife Lydia was one of the most beautiful women in the underworld, Russian confidence man Carlo Sesicovitch and his Gypsy mistress Alima; and “Little Joe” Elliott (alias Reilly), a handsome but scalawaggish super-burglar from America who loved one item more than jewels – English theatre comedienne Kate Castleton, to whom he was engaged.

(Ben Macintyre)

There was one other visitor to the American Bar, in 1873, whom Worth found interesting, even intriguing, albeit a portent. His name was William Pinkerton. It was his father who had started the Pinkerton Detective Agency with President Lincoln’s support during the Civil War and whose sons, William and Robert, now owned and ran it with a firm thumb. Robert was the businessman who rarely left his imperial office in the New York headquarters, sketching operational plans and accounting for every penny the agency spent. William, on the other hand, was more the “detective chief” who relished the hunt and the travel. His face was known and feared by every crook in many cities around the globe. While he did not have jurisdiction outside the shores of America, his presence nonetheless spelled t-r-o-u-b-l-e, for each furtive step he took across the room seemed to cry If I know where you are, the Law knows where you are.

When he walked into the bar and took a seat at one of the booths, Worth instantly recognized him, those dark features, thick mustache, heavy eyelids. For that square jaw of his had appeared hundreds of times in the dives where Marm Mandelbaum’s bunch frolicked; the meanest of them would turn ashen when William Pinkerton ambled in for no other reason than to remind them, with no more than a stare, that he existed.

Tonight, without exchanging names, Worth bought the lawman a drink and they chatted a while of light, general trivia. Each caught in the other’s face the underthoughts….both amused by this (the detective more, daresay) …Pinkerton preying….Worth prepared to duck. They talked of Paris, people they knew, and when Pinkerton left it was then, and only then, that the crook plopped back into the booth and exhaled.

Pinkerton had come to the American Bar to vex and to spook, that was obvious; it was his sign, his decree, that the Pinkertons knew about his crimes – about his desertion from the 34th New York Regiment, about his work under Mrs. Mandelbaum, about the Boylston National Bank and, probably, the tricks in Liverpool, too. What the upshot of it was was anyone’s guess. Was he telling Worth to mend his ways before he was arrested for good? Or was he telling him: If I know where you are, the Law knows where you are.?

Whatever the moral of the story, it thunder-packed. The man who had just left his bar was not one to pay a social visit for socialities’ sake. Within a few days after the detective’s departure, the American Bar was raided, then raided several more times over the winter of ’73. Evidently, Pinkerton had goaded the French Surete into action, And even though the proprietors of the gambling salon were pre-warned by the buzzer — in one case, virtually just moments before the gendarmes crashed through the front doors — they knew that their dancing days in Paris had ended. Pinkerton was known to badger badger badger; Worth knew that he would pester, pester, pester until the roof caved in. And Worth, Bullard and especially the illimitable Kitty Flynn were not partial to ceiling dust powdering their scalps.

(Ben Macintyre)

It was now time to close the American Bar. Because of its attention from the Surete, the respectable people stayed away in droves, even more than the nervous hoodwinkers and miscreants who took to regarding the hangout as a jinx. But, before he closed the shutters for its final night, Worth, to make up for the loss in profits, used the premises of the bar itself to pull off a spur-of-the-moment but nevertheless dazzling bit of grand larceny.

“Worth decided to improve matters in his traditional way,” says Ben Macintyre, “by stealing a bag of diamonds from a traveling dealer who had carelessly left them on the floor as he stood at a roulette table…Worth cashed a check for the diamond salesman and distracted him while Little Joe Elliot crept under the table and substituted a duplicate bag for the one containing the diamonds. The theft netted some £30,000 worth of gems.”

When the salesman, noticing his diamonds gone, yelled sacre bleu and other phrases unrepeatable, Worth himself summoned the gendarmes and, playing the martyr to the hilt, insisted they scour the place; if they were found on his premises, he would clap himself in irons and ask for the guillotine, the dirty dog he’d be! As Macintyre points out, Worth failed to suggest they look in the bottom of a particular barrel of beer.

Closing the bar was a task in itself. With Piano Charley Bullard gone ahead to make connections in London, their next destination, Worth and Kitty oversaw the final arrangements – the liquidation of the assets — and the careful packaging of many of the accoutrements they were shipping to London, the antiques, much of the furniture and fixtures. And while the cat, Bullard, was away, the mice played, Worth and Kitty sharing their final nights in Paris in one bed.

Adam Worth: The World in his Pocket

London

“London is such a wonderful sight… With people there moving all day and all night…”

—The Mountains of Mourne (Anonymous)

In Paris, Worth had experienced a strong taste of respectability, if not actual, then in pretense. He enjoyed it. He loved being the respected businessman, the connoisseur of fine wines, the aristocrat, the gentleman. And he planned to carry that mien to London, the center of all that was refined and fluent. If his gains were ill-gotten, to him they were merely the plunder of one sharper brain over another, mirroring what that professor named Charles Darwin was writing about in all his latest scientific texts, what he had termed so accurately “survival of the fittest”. But, Worth, in his estimation, had taken the cycle a level higher onto a more civilized plateau. His own successes were not the result of clawing and gaming as animals in a jungle fight for the larger share of meat; he stole from those who could afford it, inflicting no wounds on the innocent nor the unprepared. He was, he said, comparable to the greatest country in the world to which he was redeploying his art, Great Britain. She had lost territories and won territories, fighting always in honor, accepting defeats with humility, parading its gains with as much pomp and circumstance as the sheen on the surface of its crown jewels in London Tower.

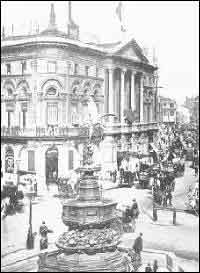

That was the Empire under Queen Victoria. And London was its hub, its treasure trove. Paris had been a prism of colors, London was grey and black and white, seeming to hang untenanted on its own fog, uplifted by an airy breath of majesty, but stable — oh, so stable! — nonetheless. Sturdy in its age and as forever as the Merlyn who defined it and as traditional as the Arthur of Camelot who shaped it. New thoughts persisted all the same in the minds of new writers like Stevenson and Thackeray and Tennyson, and in the minds of Oxford chaps like Oscar Wilde, but the new visions didn’t topple the ideal, as in Paris, but challenged it in rhetoric and in verse, as Dickens had triumphed the plight of the poor a decade earlier with A Christmas Carol.

(Courtesy The Queen’s London)

London was mystical. It preferred shadows to sunlight, whether to masquerade the decay of slums in Cheapside and Billingsgate, or to blanket the secrets caught lopsided between old-fashioned morals preached from the pulpit of St. Paul’s Cathedral and the new morality, or merely to keep itself wrapped in a reserved bubble where earthen colors kept the diorama serene. It was a world of crinoline gowns with wrist-fans and cravats with silver-knobbed canes that blended on the same avenues with ragged poplins and workman’s wrinkly whites. It emanated cobblestones and gaslight, and cross-pane windows and cross-stitched dormers over Elizabethan eaves, inch-thick window panes mirrored the glow of a ruddy British sunset and a rainy gray morning. London’s landscape brought narrow mews and dark green parks with ancient oaks and chalk-colored domes and black spires and slanted rooftops with chimneys all askew. In sunlight one might hear the clatter of carriage teams, call of the costermonger, tinkle of the muffin cart, whistle of the British “bobby” and the sacred toll of churches announcing hours, both holy and non. At night, there was very little sound, every echo cushioned on the pad of the fog.

Worth found in London what he had traveled halfway around the globe to find, a breeding spot of culture where a smart crook could be a man about town and a rogue simultaneously, where the police had little dossier on him. To London some of the best of America’s crooks had migrated ahead of the law, waiting for a new Marm Mandelbaum-like personae to lead them into temptation.

If Worth planned to be the pirate captain of these land-docked buccaneers, he knew he must begin acting more like a prosperous captain, worthy of imitation and esteem. One of the first things he did when reaching London was to purchase a capacious estate for himself, Bullard and Kitty called West Lodge, located just south of the city in Clapham Common. Set back from the streets, the manor house was an imposing red-brick two-story structure built early in the century by tallow shipper Richard Thornton and later occupied by a Member of Parliament. Worth filled his temple with expensive furniture, oil paintings, bric-a-brac, antiques and rare books, some of these items remnants of the American Bar. The huge ornate mirror that had hung behind the bar in Paris now hung in the central parlor, reflecting the hearth fire across the room, radiating a warming, amber glow across the entire mahogany chamber. On the grounds of the Common were his own private tennis court, shooting gallery and bowling green.

Worth’s residence might well have been described by a Victorian novelist whose description of a fine British estate is printed in Life in Victorian England by W.J. Reader: Of it, she wrote, “An ivy-mantled lodge with curley chimney stacks stood immediately within (an ancient gateway); and beyond, sloping gently upward for a mile or more, a straight, grassed drive between thick woods…”

Worth also leased an apartment in London’s most fashionable district, Mayfair, at Number 198 Picadilly. It was from this flat that he planned to conduct most of his criminal business. He was not naïve; he knew that Pinkerton’s men would trace his whereabouts in no time and that Scotland Yard, Britain’s constabulary, would begin dogging his tails. The more he could keep prying policemen from his social doorstep, the better it would be for his reputation as a man of high integrity among his neighbors at the Common.

(Ben Macintyre)

Maintaining the name Henry J. Raymond, he became a student of the arts and social graces, attending Shakespeare at the Lyceum, opera at D’oyly Carte, and concerts at Albert Hall. He read the latest literature, reviewed the music critiques in The Strand and Pall Mall, remained particular on British commerce, conservative in politics, and open to the issues of Parliament and Downing Street. He even attended All Souls Church near Cavendish Square where the swells worshipped. Linens and crystal came from Whiteley’s, his boots were made at McGovern’s, his suits tailored on Savile Row, the darks for business, the lights for picnicking at Hampstead Heath and racing at Ascot Turf. (He purchased a string of ten racehorses, which he stabled on the grounds of his estate.)

But, maintaining this lifestyle required money. And that’s where his pirate horde came in. With his most trusted associates acting as his lieutenants, Worth, according to author Ben Macintyre in The Napoleon of Crime, “would farm out criminal work, usually on a contract basis and through other intermediaries, to selected man (and women) in the London underworld. The crooks who carried out these orders knew only that the orders were passed down from above, that the earnings were good, the planning impeccable and the targets – banks, railway cashiers, private homes of rich individuals, post offices, warehouses – had been selected by a master organizer. What they never knew was the name of the man at the top, or even of those in the middle of Worth’s pyramidical command structure.” Therefore, if a robbery went awry – say, if a burglar was caught with the goods in his hands or a load of stolen cargo was detained wharf-side — the “little men” carrying out the orders could never divulge, even if they wanted to, the architect of the job. The most they could say is that they were carrying out orders “from on high”.

A Pinkerton report, published years later, attests that Worth’s scope far outstretched the borders of London, even of England; that his masterful hand reached across the English Channel to the Continent where he “perpetrated every form of theft – check forging, swindling, larceny, safe cracking, diamond robbery, mail robbery, burglary of every degree, ‘hold ups’ on the road and bank robbery – with complete immunity…(that) he became a clearing house or receiver for most of the big crimes perpetrated in Europe. In the later ’70s and all through the ’80s, one big robbery followed after another (and that the hand of) Adam Worth could be traced, but not proven, to almost every one of them.”

Sometimes, Worth himself would take part in a crime, but rarely. If he did so, it was for the sport of it. Also, rarely, he would confer directly with the men actually doing a job if he thought those men capable of silence. On these occasions, he would leave his house, stop at a railway station and change from his clothes to workman’s dungarees before continuing to the vicinities of Soho or Whitechapel; the scheduled parley would enact in the backroom of a rookery; after the conference, Worth would return to the station, don his gentleman’s frocks, and hire a conveyance to his doorstep. (It is doubtful he knew Victorian novelist Robert Louis Stevenson, but who more so fits the pattern of Stevenson’s anti-hero Dr. Jekyll who was wont to make midnight rendezvous as Mr. Hyde?)

To his credit, Worth never lost the principles he had gone in with, principles that he taught the top gang members – Piano Charley Bullard. Little Joe Elliott, Joseph Chapman, Charles Becker, Carlo Sesicovitch and, for a very brief time, brother John Worth. Violence was strictly forbidden. He would remind his men time and again of what had become somewhat of his motto: “A man with brains has no right to carry firearms. Exercise your brain!”

Becker

(Pinkerton’s, Inc.)

Nor would Worth tolerate excess of any kind, believing that laxity of the mind comes from excess. Intemperance was condemned. Worth worried that his partner and best friend Bullard was slowly losing himself to the bottle, and had he been any other man than Piano Charley he would have been terminated from the team.

But, while the money poured in there was trouble in paradise. First, a Scotland Yard inspector by the name of John Shore had taken it upon himself to be Adam Worth’s personal Javert. A man with a reputation among even his fellow officers as a lout and a braggart, Shore promised to have the American Worth and his vultures in chains in no time – but things didn’t work out that way. Worth’s men outstepped him at every turn, infuriating him. (Legend claims Worth succeeded in bribing two metropolitan detectives and a barrister to report Shore’s movements to him in advance.)

However, Shore did have one brief moment of victory. When Worth’s brother John sought out Adam in England hoping for a job, the older brother utilized him to run errands and deliver money for payoffs – simple tasks – for he was aware that his sibling, God bless him, did not possess what it took to be a “good” thief. His presumption was confirmed as fact when, acting against better judgment, he invited John to take part in an international forgery scheme. Scratch Becker had just cashed one of his printed checks (value £3,500) at Westminster Bank in London; now it was up to John to exchange the money to foreign currency before the bank caught its mistake. John was sent to Paris to transform the cash to francs. But, once there, the novice half-wittedly went to the very money-changing merchant his brother had warned him to avoid, Meyer & Company. Meyer had previously fallen prey to the counterfeit ring and this time, its senses sharpened, noticed the fake bill of exchange immediately. John was promptly pinched and extradited to England in the company of Inspector Shore, who reveled at his catch.

It cost Adam Worth a small treasure and long, frustrated hours of legal wrangling to convince a jury that no one had actually seen John cash the check in London; he was exonerated. Worth then cordially gave him a loyal pat on the back, a goodly stipend for his troubles and a one-way ticket on a vessel back to America.

Another near-fatal mishap occurred when Worth’s top four men – Little Joe Elliott, Scratch Becker, Joseph Chapman and the Russian Sesicovitch – were arrested in Smyrna, Turkey for passing off bad letters of credit. Becker had reproduced, in his usual exquisite manner, credit notes from bankers Coutts & Co., London. The shady quartet then went on a Continental spree, cashing them willy-nilly throughout remote parts of Europe, crossing borders with alacrity.

“The ruse got off to a good start,” Ben Macintyre records. “Some $40,000 had been collected in various cities (until) disaster struck. The foursome was arrested while trying to pass off a particularly large credit letter. They were tried in the British consular court, convicted of forgery, and sentenced to seven years’ hard labor in a Constantinople jail. John Shore of Scotland Yard was notified of the arrests and sent the Turkish police complete dossiers on each man; the Pinkertons announced that they planned to extradite the gang to the United States…Worth was beside himself with anxiety.”

(Dr. Tsukasa Kobayashi/Akane

Higushiyama)

He then did what had worked before, this time on a larger scale. He bribed the officials. Sailing to Turkey with Lydia Chapman, he offered thousands (the sum has never been revealed, but rumor claims it nearly broke Worth) to jailers, police and judges to set the men free. It worked, and the convicts were suddenly “ejected from prison as suddenly and as violently as they entered it,” says Macintyre.

Problems were domestic, too. Bullard’s drinking worsened. Because of his inebriation, which was becoming chronic, he and Kitty were drifting apart. They had had two children, Lucy and Katherine, but even his love for them couldn’t prompt Bullard to sober. Under the haze of liquor, he would disappear for days on end behind the clap-trap walls of cheap houses and brothels in the East End. Midnight squabbles were par for the course when Bullard teetered back to the Common. Then, after a day’s respite, the Piano man would be gone again. Kitty’s patience evaporated. Eventually, she discovered that her husband was bigamous; he had married in New York prior to their engagement and his wife had sent detectives worldwide in search of her wandering boy.

That broke it, and she turned Bullard from the bed. Without the prospect of love, her husband left the Lodge for good, this time bound for New York. Kitty, after his departure, puttered in London a while, taking her children shopping and to the theatre, but she was obviously discontent and angered by her luck. Nights, she found at least sexual comfort in Worth. To prove his adoration for Kitty, whom he had always wanted, he bought her a 110-foot yacht and christened it Shamrock in her honor.

But, his bed nor his devotion were not enough to placate the fiery, betrayed Irish lass. Without much notice, and despite Worth’s pleas, she packed up her daughters and their belongings and returned to the United States. Nothing he could say would keep her there, with him. At last, he relented, dividing the spoils with her and tossing in an extra dowry because he often wondered if perhaps Katherine and Lucy were really his children, after all.

Adam Worth was heartbroken as he stood in the bay-front window of the Lodge and watched the woman – one for whom he would have given up his fortune for if she had asked – climb into the caleche and close the door beside her. As the buggy wobbled off the grounds, he must have thought that there went the only woman he would ever idolize.

He was wrong.

Adam Worth: The World in his Pocket

Duchess of Devonshire

“An aspiration is a joy forever.”

— Robert Louis Stevenson

In the spring of 1876, a sensation hit London. She was Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, dead 70 years but still a controversial, beautiful figure staring down from canvas in a painting done by the celebrated Thomas Gainsborough in the late 1780s. Because Gainsborough had caught so well her ethereal nature, her come-hitherness, and coyly transplanted the sensuality that was Georgiana through brush stroke, the duchess again enraptured the hearts of London and tagged men’s souls. And now, nearly a century after she sat for her portrait – a portrait which sold for more than a painting had ever sold — she had won the heart of Adam Worth. He found her exquisite, beyond description.

Georgiana Spencer, Duchess of Devonshire, had been, in her time, considered to be the most glamorous, most accomplished, but most shameless, wickedest woman in Georgian England. Her lifestyle, one of decadence, of libation, of free sex (including a menage a trois between her husband, the fifth Duke of Devonshire, and his mistress), had fueled many a gossip in her day. When she sat for her portrait, scholars believe about 1787, Gainsborough sought to translate to art more than the oyster white surface of this comely woman; he strove to flush up from within her the mischief and sensuality that was his subject. And achieve he did. In his painting, she seductively poses, sunlit curls surrounding her face, framed by a large hat of noble French design, decorated by plumage, her fingers caressing a rose in a suggestive manner, one eyebrow arched, her eyes burning with desire. (It was later said a man could light his pipe by the fire in her eyes.)

Devonshire

(Ben Macintyre)

After Gainsborough presented it to the House of Spencer, the painting disappeared. It was rumored hat Georgiana’s husband had it removed from over the family mantle when she became pregnant by another man. Either way, its whereabouts became a mystery. After her death in 1806 she and the painting faded from memory. However, in September, 1841, art dealer John Bentley discovered it quite by accident hanging in the parlor of a retired schoolmistress named Anne Maginnis. Mrs. Maginnis had no idea how her late husband had acquired it, but seeing that Bentley wanted it so badly, agreed to sell it to him for the sum of £56 – probably one of the best deals ever perpetrated by a connoisseur of art.

In the 1860s, Bentley sold it in turn to silk merchant and Member of Parliament Wynn Ellis, who owned one of the largest art collections in England. What Ellis paid is unknown, but one can gather that Bentley exceeded his investment. When Ellis passed away in 1875, he bequeathed his vast number of original works to Britain, some 402 paintings, some the works of the “old masters” like Rubens or Gainsborough. From these, the National Gallery selected 44 of the best to sell off through Mssrs. Christie, Manson & Woods of London, the finest art auctioneers in the world. The Duchess of Devonshire was among them.

The auction, which opened in May, 1876, was banner news, the rediscovery of Georgiana’s portrait the main aspect. The London Times rang with praises for Gainsborough’s work and again London’s social pages were filled with stories, legendary and documented, about the Lady Spencer. As had been a decade previously, the Duchess of Devonshire was top gossip in the drawing rooms of the wealthy. The sordidness of her life tickled the antitheses of the new morality, and the independent fire that was the duchess charged the women’s suffragette movement throughout England. As well, the fashion world capitalized on the hullabaloo; the faces of Victorian ladies suddenly adopted the same ivory skin complexion with the certain amount of cheek and lip rouge to give a woman “that royal pout,”. And women began wearing wide-brimmed bonnets, plumed, not unlike the duchess’. (In the Sherlock Holmes mystery, A Case of Identity, author Arthur Conan Doyle describes a female character as wearing “a large curling red feather in a broad-brimmed hat which was tilted in a coquettish Duchess-of-Devonshire fashion over her ear”.)

Poets fashioned verse about her, some good, though most of them awful, but all published in the newspapers or the society magazines of the time. Peter Pindar donated one of the worst, some of which reads:

Oh, sacred be her cheek, her lip, her bloom

And do not, in a lovely dimple’s room,

Place a hard, mortifying wrinkle.

The auction began May 5, 1876. Right from the start three prospective buyers shot forward, all from the social zenith: the Earl of Dudley (long a lover of art with a palatial estate to show it off), Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild (a giant in the financial industry) and William Agnew (art dealer, whose new art gallery at 39 Old Bond Street was the talk of the town). While the crowds of London marched through Christie’s gallery in droves, deals were being talked up in the back rooms among the dealers and bidders.

At last, Agnew the dealer’s years of experience won out. He grabbed the biggest and most talked-about prize of the decade for 10,000 guineas, what today would amount to $600,000 – a whopping sum in 1876.

Before the end of the month, Adam Worth would steal it.

* * * * *

To view it and, more importantly, to case the layout of the studio, Worth brought one of his two partners in crime along with him that day. (Little Joe Elliott remained back at the Lodge, waiting for their return.) The man who accompanied Worth this day was his personal valet, Jack Phillips, better known as “Junka” for the amount of trash he was prone to carry about in his pockets. Dressed in striped trousers and tails of a gentleman’s gentleman, Junka was anything but. A former wrestler and ongoing thug, Worth had hired him strictly as bodyguard. Junka bore a towering frame, barrel chest, grizzled mustache and a face that, to quote Worth biographer Ben Macintyre, “looked like it had been carved out of parmesan cheese”; he was the perfect deterrent to anyone out to accost his boss.

Pinkertons (Ben Macintyre)

The odd couple purchased two tickets to the exhibit and followed the line of sightseers to the second floor gallery where the Duchess of Devonshire was on display under the soft glow from two gas jets. The valet, who it is doubted could spell the word “art,” grunted and grumbled and growled at this waste of an otherwise pleasant afternoon.

Beside him, Worth took no notice of Junka’s impatience. Having laid his eyes on the masterpiece, Worth swooned, bewitched. He had expected to be magnetized by the face of oncoming wealth – rather, he was overcome by the woman in the gild frame. Her flame, her tempestuousness dazzled him and he fell in love, deep, penetrating hot love that he knew from first glance would hardly die.

She was Kitty Flynn, and more. She was Venus, and more.

Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, staring at his own painting, found new meaning in the beauty of youth; Worth found new meaning of youth in beauty. His life had been one passing theft after another, year after year, a rabid pursuit of money and riches, most of it leaving his hands as quickly as he touched it. But, here in Georgiana there was an eternity of riches, a glory more steadfast than a bank-full of British pounds. To steal such a bounty was in itself so heady it made his head reel. But, to have her, for as long as he wanted – for she, unlike Kitty, would never drive away in a caleche — was numbing. Her age wouldn’t whither, her spoils would increase, and that light in her eyes would never diminish. He truly felt that she was smiling at him. Daring. Promising.

* * * * *

Junka Phillips and Joe Elliott would serve merely as lookouts. For this theft, Worth preferred to be the exclusive hands-on man, for he could not abide rough hands yanking at the priceless canvas. He had spent long hours over candlelit volumes studying how paintings are framed and how they must be removed from their frames so that no harm can come to them – and how to preserve their sometimes ages-old delicacy. These hours were not to be spent in vain.

small scruples (Ben Macintyre)

Near midnight, the three men returned on foot to Old Bond Street, now foggy and deserted. Lanterns flickered through the veneer on the facade of the studio, its red brick almost brown in the meager light. Joe Elliott ducked into the deep recess of a doorway at the corner of the street, where it melted into Picadilly; Junka followed his master a few steps further. The two remained in the shadows, dodging what gaslight there was. They stopped before a hand-painted shingle that read, “Thomas Agnew & Sons,” immediately below a high arched window. One quick glance in either direction of the darkness, Worth nodded and the valet stitched the fingers of his two beefy hands together to form a stirrup, hoisting the other towards the sill. Worth, above him, pried open the casement with a small crowbar while Junka pushed him upwards through to the room beyond.

It was a daring robbery. Writes Ben Macintyre in The Napoleon of Crime: “The room was unfurnished and unlit, but by the faint glow from the pavement gaslight a large painting in a gilt frame could be discerned on the opposite wall…The woman in the portrait…gazed down with an imperious and inquisitive eye…The faint rumble of a night watchman’s snores wafted up from the room below…Extracting a sharp blade from his pocket, with infinite care (Worth) cut the portrait from its frame and laid it on the gallery floor. From his coat he took a small pot of paste (and) daubed the back of the canvas to make it supple and then rolled it up with the paint facing outward to avoid cracking the surface, before slipping it inside his frock coat…The stolen portrait (was) pressed to his breast.”

“All the things I like to do are either illegal, immoral or fattening.”

— Alexander Woollcott

Over the next several months, Adam ruminated. He had told his helpers that, after a sensitive waiting period, he would attempt to sell the painting — but that had been before he realized the Duchess of Devonshire’s aesthetic value. Now here he was – caught between practicality (he needed money since the bribery of Turkish officials had exhausted his bank account) and a romantic soul that seemed to have been waiting for indulgence. At 35 years old, he knew enough not to be cornered by a pretty face on canvas, but maturity and intelligence aside, he found himself unable to let go of what she symbolized. She was tranquility in his life, a cornucopia of self-satisfaction, a reward for many hard years of labor and fretting. She was all this, and demure, elegant, erotic. She was his paragon. She was his.

Under an alias of Edward A. Chattrell, Worth made a few half-hearted attempts to make contact with art dealer Thomas Agnew, but really did not know why…maybe to please his accomplices who hungered for their share. Across London, Agnew was hysterical. Unbeknownst to Worth and the rest of the world, Agnew had opted to re-sell the painting for a profit to millionaire financiers Junius Spencer Morgan and his son J. Pierpont Morgan, whose lineage stretched back, although thinly, to Lady Spencer. Having discovered that Georgiana was a relative, Morgan coveted the monument.

Worth displayed no real drive to sell the portrait. And Junka Phillips and Little Joe were tearing at the seams. Their boss attempted on several occasions to placate them with cold cash, but when they spent it – which both did immoderately – they were back pecking at Worth’s heels. When he refused to give them more, both “friends” tried to betray him.

(Ben Macintyre.)

One evening, not long after the heist at the art gallery, Junka invited Adam Worth for a leisurely ale at the Criterion Bar, a drinking establishment near Picadilly Circus. Worth thought at the outset that something was odd. Junka was never one for social graces nor a habitue of the Criterion, a meeting place of the literati. When they arrived, Worth observed a man in bowler seated in the booth beside the one that Junka chose; the stranger sat alone and obviously craning to hear every word they spoke. The attentive one had policeman written all over him. What’s more, Junka was none-too-subtly attempting to draw Worth into a conversation about the night they stole the Duchess of Devonshire. Clearly, Junka was selling him out. For the first — and last — time in his criminal career, Worth resorted to violence. Though a much smaller man than the behemoth, the Napoleon of crooks turned wrestler and vaulted over the table to tar the stunned Junka. Leaving the latter gasping on the floor, soaked and sore, Worth tipped his hat to the spy across the way and sauntered outside. He and Junka would never associate again.

Joe Elliott was getting the yen to return to actress sweetheart Kate Castleton, whom he had deserted a year earlier, and demanded that Worth dish out for the passage. To avoid another such confrontation as the one with Junka, Worth relented.

Once in New York, Elliot paid a brief visit to his love, but paid more attention to the money vaults at the Union Trust Company. Arrested, he was tried and sentenced to seven years in The Tombs, a castellated lockup for felons. Feeling that he wouldn’t be in this position if Worth had coughed up his share of the Gainsborough, Little Joe squealed loud and clear to the Pinkertons. William Pinkerton in turn notified Scotland Yard. But, because Elliott could not substantiate his accusations by telling them exactly where Worth hid the portrait, his demonstrations were merely that. The Pinkertons and the Yard had already known for some time that Adam Worth was the thief – Elliott’s news had not been a revelation. The robbery bore all the characteristics of the gentleman bandit. But, until the painting could be traced and directly linked to him, the police could do nothing.

Castleton

(Ben Macintyre)

Worth remained cognizant that he might be sitting on dynamite. He knew that it could be a matter of time before his places – West Lodge in the Common and his Picadilly apartment – were raided. Since the night he brought the Duchess home, he had been continually shifting her to various hiding places in his mansion; the artwork spent a lot of time beneath his mattress and in his attic. Whether he traveled overseas or on a one-day gadabout outside London, the Gainsborough went with him, concealed in a specially made Saratoga trunk with a false bottom. It also accompanied him on several criminal forays meant to replenish his bank account since the loyal but fund-draining Turkey debacle. One of these was in Paris when he and two crooks named Captain George and William Megotti broke into the money car on the Calais Express, garnering 700,000 francs’ worth of Spanish and Egyptian bonds.

As the 1870s rolled to an end and his gang slowly evaporated, either because its members returned to their respective countries or because they were arrested while performing crimes apart from the Worth circle, the duchess’ owner realized that perhaps he and the Gainsborough should vacate Londontowne for a long holiday.

He chose as his destination Cape Town, South Africa. The trip was actually intended to be (as Worth later admitted) more business than pleasure. He wanted to see first-hand the area’s diamond fields that acquaintances had told him about. “Having surveyed the criminal landscape (there), he concluded that uncut diamonds represented an excellent, portable, and easily exchangeable form of cash. As an accomplice, he brought along one Charley King, described by the Pinkertons as ‘a noted English crook,'” relates Ben Macintyre in The Napoleon of Crime. “The diamond fields…had already proved a magnet for a diverse mixture of visionaries and vagabonds…Two more crooks in the multitude would not stand out, and with diamonds being hauled out of the earth at a prodigious rate, the thieving opportunities were tremendous.”

Not one to soil his hands digging, but to reap the profits afterward, Worth took note of how the diamonds in the rough were carried by horse-drawn wagons over rough terrain from the mines near Cape Town to Port Elizabeth on the coast. There, they were loaded upon steamers bound for Europe. Each convoy was guarded by a small band of armed Boers with repeating rifles. Worth and King attempted to hold up one of these wagon trains, western-style, on a mountain road. But, the Boers were not ones to throw down their carbines; the bandits retreated empty handed and within inches of their lives. King continued to run long after Worth slowed down.

Bereft of his quivering partner, but not discouraged, Worth acted alone. This time he would act in a gentleman’s manner, the way to which he was accustomed. His brain slid into gear. Striking up a conversation with some of the cargo folks in town — the men who loaded the diamonds — he learned that the teamsters hauling the gems were often stalled because of bad weather and rising waters along the hilly topography. If the express cargo missed the steamer at Port Elizabeth, the diamonds were deposited in the safe at the town post office and held in the vault until the arrival of the next freighter. Worth had a brainstorm and rushed to Port Elizabeth.

There, in disguise of a feather merchant, he befriended the elderly postmaster. Turning on charm, he would stop by the office daily and play chess with the lonely old man until he worked up such confidence that he was allowed to wander practically throughout the station. At one point, when the postmaster left his counter to retrieve a customer’s package from the back room, Worth pocketed the vault key, had a wax impression made, and returned it before the old fellow noticed their absence.

All he had to do now was make sure the next scheduled shipment of diamonds would miss the boat. That was the easiest part: He rode horseback to the ferry crossing several miles east of Port Elizabeth and, arriving there a few hours before the coming convoy, simply slashed the rope that secured the flatboat, allowing it to drift downstream. The express was delayed eight hours and its cargo had to be unloaded for safekeeping in the post office that night.

When the freight men turned out at the safe the next morning, they found its door open and the gems — $500,000 worth of them — gone to oblivion.

Adam Worth: The World in his Pocket

Mr. Raymond Takes a Wife

“Increased means and increased leisure are the two civilizers of man.”

— Benjamin Disraeli

The diamond theft in Africa began just one more sideline to Worth’s constantly growing list of illegal businesses. Upon returning to London after the escapade, he hired a clever and educated crook unknown to Scotland Yard by the name of Ned Wynert. With him in place as the overseer of the new enterprise, he established a pseudo-legitimate corporation called Wynert & Company and opened shutters in the middle of London’s jewelry center, Hatton Gardens. By marking their merchandise a pound or two less than the standard retailer, they fared well. The take from the diamonds stolen at Port Elizabeth was £90,000.

“The 1880s were years of consolidation and prosperity for Worth,” reads Ben Macintyre’s The Napoleon of Crime. “He had become what Pinkerton called ‘a silk glove man,’ a gentleman crook and sporting gentleman of leisure luxuriating in his loot and a cut above the vagabonds and rascals with whom he had once associated. From Hatton Garden, Ned Wynert…ran the day-to-day criminal business while Worth enjoyed his yacht and his horses, traveling whenever the fancy took him, gambling and entertaining his friends, some criminal but many of unimpeachable respectability.”

Friend Eddie Guerin, whose memoirs give insight into Worth during these years, visited him in 1887, the year of the Queen Victoria’s Jubilee. Guerin hadn’t seen Worth since his Paris days and was amazed to see how far an German-born Jew had come in the City of London. He writes, “If ever a man in this world could be pointed out as an exception to the rule that no crook ever makes money it was Adam Worth. He owned an expensive flat in Picadilly, he entertained some of the best people in London who never knew him for anything but an apparent rich man of Bohemian nature.”

(Courtesy Leeds Art Gallery)

The decade began with promise. In November, 1881, the two centrals behind Wynert & Company robbed the central post office in the Hatton Garden district and walked away with more diamonds, uncut. Worth’s establishment, literally down the street from that post office, mounted them so that they were untraceable, and sold them for £30,000.

It was in the early 1880s that Worth took a wife. When he first had come to London from Paris, as “Henry Judson Raymond,” he had stayed in a small hostelry in Bayswater, run by a widow and her two daughters. The family treated him kindly and they remained friends, even as Raymond became a man of leisure. Months after his brief lodging, after he moved into his estate in the Common, Worth learned that the family was in dire financial straits. He began to help them, furnishing them with a residence for free and putting the daughters through school. As the children grew, the youngest of them blossomed into a particularly beautiful young lady to whom Worth suddenly found himself attracted. Feeling himself now a suitable member of the upper class social caste, he thought it befitting that he marry. He asked for the girl’s hand in marriage; she accepted with delight.

She nor her family never knew Worth’s real identity; to them he had always been Henry Raymond, American gentleman come to England, sporting blood, businessman, benefactor and now diamond merchant. The wedding was a social affair and the Raymonds settled down to a blissful marriage in West Lodge. Worth sold off his Picadilly apartment, no longer desiring a “bachelor flat”.

None of Worth’s biographers are able to give a name of his bride, but evidently she was a domestic woman of virtue and much unlike the ambitious women he had known, far removed from energized Kitty Flynn. While Sophie Lyons’ reminiscences claim theirs was not a romance of passion, they were nevertheless happy. Worth proved to be a faithful husband and, when his wife gave birth to a son, Harry, in 1888, and a daughter, Constance, in 1891, a joyous father.

“Worth was riding on the leaf of his silk hat – wealthy, respectably married and increasingly powerful,” Macintyre notes. “He would periodically carry out a robbery to keep his hand in and demonstrate his prowess, if only to himself – he being the only critic whose opinion he truly valued.” Jobs were easy to the criminal whose mastery had become second nature. To illustrate, he walked into the Bank of London carrying a forged note of delivery for £35,000 worth of gems – and walked out with the gems.