Anthony Pellicano: Wiretapper to the Stars — “Stop” — Crime Library

It all started with a dead fish with a red rose in its mouth. In 2002, freelance reporter Anita Busch had found both items on the smashed windshield of her car along with a note that simply said, “Stop.” At the time, Busch was writing separate articles about actor Steven Segal’s involvement with the Mafia and former super-agent and short-lived Disney president Michael Ovitz’s difficulties re-establishing himself as an agent. Busch reported the incident to the police, who initiated an investigation.

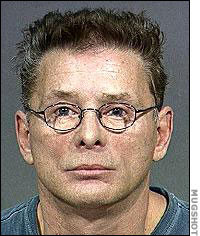

Later that year an FBI informant secretly recorded a career criminal named Alexander Proctor, 62, admitting that he put the fish, the rose, and the note on Busch’s car, and that he had done it for Los Angeles private eye Anthony Pellicano. In that same conversation, the German-born Proctor, who has several drug convictions on his record, bragged that he “could sell a million of ’em,” referring to Ecstasy pills.

As a result of Proctor’s incriminating statements on tape, FBI agents obtained a warrant to search Anthony Pellicano’s office on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. In November 2003, agents found two hand grenades, a brick of C-4 plastic explosive, and $200,000. Pellicano pleaded guilty to weapons charges and was sentenced to 30 months in prison.

But the truly explosive material was uncovered in a subsequent FBI raid on his office. Following a lead that Anita Busch’s telephones had been tapped, agents returned to Pellicano’s office on January 14, 2003, looking for evidence of wiretapping. The agents penetrated Pellicano’s “War Room” and seized “11 computers, including five Macs, 23 external hard drives, a Palm V digital assistant, 52 diskettes, 34 Zip drives, 92 CD-Roms, and two DVDs,” according to Vanity Fair. This equipment contained “3.868 terabytes of data,” the New York Times reported, “the equivalent of two billion pages of double-spaced text.” The content of these electronic files was Pellicano’s work product as Hollywood’s wiretapper to the stars, illegally intercepted telephone conversations of the rich and famous. Some of these wiretaps were ordered by powerful attorneys and executives seeking an unfair advantage in legal disputes. Some of the intercepted conversations concerned personal matters, like divorce and child custody disputes. Much of it was business as usual, Hollywood-style. All of it was obtained illegally.

As news of the seizure of Pellicano’s files spread like brush fire, people in the “biz” became very nervous. Many of Hollywood’s top movers and shakers had used Pellicano’s services or had retained attorneys who did. If the FBI listened to those tapes, indictments would certainly follow. Hollywood held its breath, waiting to see where the ax would fall.

Godfather’s Don Corleone

The only thing that currently stands between many of Hollywood’s elite and a perp walk is Anthony Pellicano himself. His audio files are protected by sophisticated encryption software and only he knows the passwords. On the day he was scheduled to be released from prison on the explosives violation, he and six of his cohorts were hit with a 112-count indictment for wiretapping and illegally using law-enforcement databases for the purpose of “securing a tactical advantage in litigation by learning their opponents’ plans, strategies, perceived strengths and weaknesses, settlement positions and other confidential information.” Pellicano was denied bail and remains incarcerated. Though he seems to be between a rock and a hard place, he is in many ways the most powerful man in Hollywood. If he were to cut a deal with the government and give them access to his audio files, many prominent figures in Tinseltown would have to face trial.

Undoubtedly Pellicano is not enjoying imprisonment, but he is probably savoring the fact that he’s holding all the cards. A self-styled tough guy from the streets of Chicago, he sees himself as the “Don Corleone” character in The Godfather, according to Vanity Fair. In fact, he even named his son Luca after Don Corleone’s favorite enforcer, Luca Brazzi.

Pellicano joined the Army after being expelled from high school and was trained as a cryptographer for the U.S. Army Signal Corps. After his stint in the service, he returned to Chicago, where he took a job with the Spiegel catalogue’s collections department, specializing in locating delinquent customers. In 1969, he went into business for himself as a private investigator. He became very interested in electronics and stayed current with the latest in espionage technology.

In the 1970s, he landed a few high-profile clients and got his name in the papers. Yoko Ono hired him to track down her missing daughter. In 1977, he found the body of Hollywood producer Mike Todd, who was Elizabeth Taylor’s third husband. Todd had died in a plane crash. After his burial in Chicago, robbers looted the grave, looking for jewelry. The body had disappeared, and the Chicago police performed an exhaustive search of the cemetery. Days later Pellicano led a group of reporters directly to the spot in the cemetery where Todd’s remains were hidden under a pile of leaves, a feat detectives at the time found “suspicious.”

Pellicano eventually tired of Chicago. He felt it wasn’t the kind of city where he could put his best talents to use. He wanted a place that needed a “sin eater,” his term for someone who could make the sins of the rich and powerful vanish. He decided that Los Angeles was his kind of place, and in 1983, he moved there.

In Los Angeles, Pellicano earned a reputation as Hollywood’s pit bull. In the early 1990s, whenever a tough guy was needed to make a problem go away, Pellicano was ready, willing, and able. According to Vanity Fair, he managed to squelch a story that had run in a British tabloid accusing actor Kevin Costner of having had an improper relationship with a young fan. When an ex-boyfriend started harassing actress Farrah Fawcett, Pellicano was called in to set the man straight. When singer Stevie Wonder suspected his girlfriend of disloyalty, Pellicano spied on her. O.J. Simpson hired him to deal with a pesky secretary. Rosanne asked him to find her long-lost daughter. When actor James Woods complained that actress Sean Young just wouldn’t leave him alone, Pellicano intervened. When a 13-year-old boy accused the King of Pop, Michael Jackson, of sexual abuse, Pellicano uncovered damaging information about the boy’s family that compromised his credibility as a witness against Jackson. Pellicano’s work on the Michael Jackson case put the P.I. into the limelight. It became common knowledge in Hollywood circles that if a sin had to be eaten, Pellicano was the man for the job.

Pellicano’s style often mimicked the noir crime films of the 1940s. Jude Green told a federal grand jury of her encounters with Pellicano while she was in the midst of a contentious divorce from her wealthy financier husband, the late Leonard I. Green, in 2001. As reported in the Los Angeles Times, on one occasion, Pellicano followed her to a dog-grooming parlor in Santa Monica and blocked her car with his. When she tried to leave, he got out of his car and stood in her way with arms folded, sunglasses covering his eyes, not saying a word. Later that same day, he followed her to a coffee shop and blocked her car again, silently menacing her in the same way. According to Pellicano’s indictment, he illegally accessed a police database in 2001, searching for damaging information about her. She claimed that in 1997, when she refused to sign a pre-nuptial agreement, her husband threatened to “sic” Pellicano on her. Leonard Green’s attorney in the divorce was Dennis Wasser, who, according to Vanity Fair, had used Pellicano’s services regularly. In the past, Wasser has represented Jennifer Lopez, Steven Spielberg, and Rod Stewart in divorce proceedings.

Pellicano is an acknowledged expert in the technology of audio surveillance and has worked for the FBI on several occasions, turning garbled intercepts into usable evidence. In 2001, he helped the FBI analyze wiretap evidence against Sammy ‘the Bull’ Gravano, former underboss of the Gambino crime family in New York, who had relocated to Arizona and started dealing drugs in quantity there. Gravano was tried and convicted of narcotics trafficking.

Pellicano had compiled an impressive collection of electronic surveillance gadgetry, which he kept in his fabled “War Room,” a locked room in his Sunset Boulevard office. He also commissioned custom surveillance software to handle with his extensive wiretapping activities. One of his programs, Forensic Audio Sleuth, could clarify barely audible recordings. Another program that he developed, Telesleuth, was designed to intercept wiretapped phone calls automatically. Pellicano would routinely record hundreds of hours of telephone conversations when working on a case, but rather than hire people to listen to every minute of what he recorded, he used a Telesleuth feature that graphed the volume of the speakers’ voices. Pellicano knew from experience that the best information came when people raised their voices, and his software automatically picked out those conversations.

Prosecutors allege that Pellicano bribed two police officers to illegally check law-enforcement databases for criminal and driving histories. Officer Craig Stevens of the Beverly Hills Police Department pleaded guilty to charges prior to the Pellicano indictment. Officer Mark Areson of the Los Angeles Police Department was indicted along with Pellicano, as was Rayford Earl Turner, a Pacific Bell worker who gave Pellicano confidential telephone records and installed wiretaps on phone lines for him. Another PacBell employee, Teresa Wright, pleaded guilty before the indictment was announced.

Among the witnesses against Pellicano is his girlfriend, Sandra Will Carradine, the ex-wife of actor Keith Carradine. Ms. Carradine had hired Pellicano when she was divorcing her husband in 1993. (Keith Carradine subsequently sued Pellicano for harassment.) After being indicted in January 2006, she pleaded guilty to two counts of perjury in the Pellicano case and decided to cooperate with the FBI. She testified that during a series of jailhouse visits with Pellicano in December 2005, Pellicano spoke of his wiretapping activities but tugged on his ear rather than using the word wiretap, according to the New York Times. In one conversation, he admitted that he had passed on information obtained from wiretaps to prominent divorce attorney Dennis Wasser.

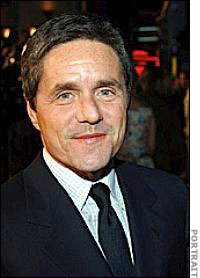

Former talent manager and current chairman of Paramount Pictures Brad Grey is mentioned in the Pellicano indictments with regard to wiretapping and background checks of individuals involved in litigation with Grey. For his part, Grey maintains that Pellicano was merely a casual acquaintance and that he never used Pellicano’s services. But a former Pellicano employee told Vanity Fair that Grey and her boss spoke on the phone “at least once a day, every day.” Grey’s attorney, Bert Fields, was alleged to have routinely used Pellicano’s services on behalf of his clients.

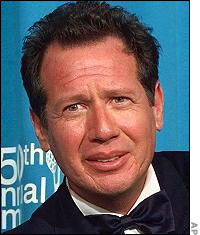

In 1998, comedian Garry Shandling sued Grey, who had been his manager, for $100 million, contending that Grey had swindled him out of profits from the hit HBO comedy The Larry Sanders Show. Shandling’s lawyers accused Grey of “triple-dipping,” taking a 10% manager’s fee on Shandling’s earnings, $45,000 per episode, and 50% of the show’s eventual profits, according to the New York Times. Pellicano’s indictment charges that the private eye ran unauthorized background checks on Shandling; his girlfriend at the time, Linda Doucett; his business manager, Warren Grant; his personal assistant, Mariana Grant; his friend, comedian Kevin Nealon, who was also managed by Brad Grey’s company; Nealon’s wife; and another friend, Gavin de Becker, the well-known security consultant. De Becker had warned Shandling that Pellicano would use extra-legal means to give Bert Fields a tactical advantage in negotiations, including tapping Shandling’s phones and stealing his garbage to look for anything that could be used against him. In July 1999, Shandling and Grey settled their dispute, and Grey agreed to pay Shandling $10 million. When the FBI raided Pellicano’s office and found his files on Shandling, the extent of the private detective’s illegal snooping was finally exposed.

In another instance, Grey allegedly hired Pellicano to investigate a screenwriter, Vincent ‘Bo’ Zenga, who was suing Grey for a share of the profits earned by the film Scary Movie. Zenga claimed that he had made an oral agreement with Grey’s company, Brillstein-Grey Entertainment, to co-produce Scary Movie, which became a hit in 2000. Grey contended that there was no such oral agreement, that Zenga had inflated his credentials, and that Zenga had agreed in writing to take a smaller share of the profits. Both men were forced to endure hardball depositions from opposing attorneys in which they conceded damaging information about themselves. After Grey’s three-day deposition in early February 2000, Pellicano ordered background searches on Zenga and his brother. According to the New York Times, Pellicano produced transcripts of recordings of Zenga’s telephone conversations starting on February 14.

In a conversation between Zenga and his attorney, Gregory S. Dovel, Pellicano overheard Zenga criticizing his partner, Stacy Codikow. Grey’s attorneys were able to exploit this rift between the partners, causing Codikow to reverse part of her previous testimony. Zenga’s lawyers feel that this lost the case for them.

“When Pellicano came in,” Dovel told the New York Times, “it was like a bomb exploded. It was like they had access to everything… If they could take Stacy Codikow, a friend of Bo’s, and the next thing you know, she’s openly lying — what else is he going to be able to accomplish?”

The hot lights of the government’s investigation of Pellicano have also fallen on Michael Ovitz, former Disney president and at one time the most powerful agent in Hollywood. Ovitz has not been charged, but curiously the indictment against Pellicano and his associates includes a list of wiretap victims who also happened to be adversaries of Ovitz.

Ovitz left the agency he’d founded, Creative Artists Agency, to take the job at Disney in 1995. After Ovitz’s brief and tumultuous tenure at Disney, he attempted to get into in the management business, setting up a new company, Artists Management, in 1999. He tried to recruit clients and employees from his old company, but two of CAA’s top agents, Bryan Lourd and Kevin Huvane “waged open war” on Ovitz’s new company, according to the New York Times. According to Pellicano’s indictments, he paid a source in the police department to run a check on the motor-vehicle records of Lourd and Huvane.

In March 2002, sports agent James Casey sued Ovitz and Artists Management for $450,000 over a disputed finder’s fee regarding Boston Celtics basketball star, Paul Pierce. The FBI learned that Pellicano had run a criminal check on Casey.

In May 2002, Pellicano ordered a criminal check on former Artists Management executive Arthur Bernier, who was in the process of suing Ovitz for wrongful termination.

In the spring of 2002, New York Times reporter Bernard Weinraub and freelance journalist Anita Busch collaborated on seven articles concerning Ovitz’s business difficulties. On May 16, according to prosecutors, Anthony Pellicano arranged to have both their names put through the FBI’s National Crime Information Center database. Pellicano was also wiretapping Busch’s telephones at the time.

Ovitz has maintained that he had no direct dealings with Pellicano and that his attorneys hired the private investigator to work on the Bernier and Casey cases when Ovitz declined to select a private investigator for himself. But one of Pellicano’s former employees told Vanity Fair that her boss had been doing personal work for Ovitz since 1996 and that the two men were “good friends and would speak to each other on a daily basis.”

Interestingly, the Pellicano-Ovitz connection sheds new light on the dead fish incident, opening the possibility that it was Ovitz and not actor Steven Segal who wanted to scare off reporter Anita Busch. “The FBI has all but cleared the actor of involvement,” Vanity Fair stated.

Even more interesting, Gorry, Meyer & Rudd, the law firm that represented Michael Ovitz, sued Steven Seagal for failing to pay a $260,000 legal bill. The firm hired Pellicano to collect it.

On February 15, 2006, federal prosecutors indicted Hollywood attorney Terry N. Christensen. He was the first high-profile figure in the entertainment business to be indicted in connection with Pellicano’s wiretapping activities. The government charged Christensen with paying Pellicano $100,000 in 2002 to tap the telephones of Lisa Bonder Kerkorian, the ex-wife of 89-year-old billionaire Kirk Kerkorian, the former owner of MGM and currently the largest shareholder in General Motors. At the time, Mrs. Bonder Kerkorian was suing Mr. Kerkorian for an increase in child-support payments from $50,000 a month to $320,000, including, according to Vanity Fair, “$6,000 a month for house flowers and $150,000 a month for private jet travel.” The couple have one child.

The Kerkorians’ marriage lasted 28 days, though they had been dating for 11 years. Mr. Kerkorian did not believe that the little girl was his and felt that his ex-wife had tricked him into thinking that it was. The dispute began in 1999, and embarrassing details of Kerkorian’s lavish spending have appeared in the press. Kerkorian was represented by attorney Terry Christensen. According to the indictment, fellow attorney Bert Fields advised Pellicano to contact Christensen about “going after” Mrs. Bonder Kerkorian’s attorney, Stephen A. Kolodny. Three days after the court ordered Mr. Kerkorian to pay $225,000 to Kolodny for his ex-wife’s legal bills, Christensen paid Pellicano $25,000 to start tapping on her phones.

On April 28, 2002, Pellicano reported to Christensen that he had intercepted conversations between Mrs. Bonder Kerkorian and her lawyers in which she discussed the child’s actual biological father, Hollywood producer Steve Bing. Kerkorian and Christensen visited Bing the next day and asked him if he would take a DNA test. Bing refused, but another investigator hired by Kerkorian went through Bing’s garbage and found a piece of used dental floss with which a lab was able to prove that he was indeed the father of Mrs. Bonder Kerkorian’s child.

A California court reduced Mrs. Bonder Kerkorian’s request and ordered Mr. Kerkorian to pay her a little over $50,000 a month.

With regard to the charges leveled against Terry Christensen, Assistant U.S. Attorney Daniel Saunders told the New York Times that Christensen had used the information illegally retrieved by Pellicano and “changed the playing field… No attorney should stoop to such a level to gain a tactical advantage.”

But with this indictment, Hollywood started sweating. The government wasn’t just going after tough guys and techies. They were going after the big fish. People who had used Pellicano’s services in the past had good reason to be worried.

In April 2006, director John McTiernan got caught up in the snowballing Pellicano investigation and pleaded guilty to having lied to FBI agents about hiring Pellicano to wiretap a business associate. In the summer of 2000, McTiernan, the director of the hit movies Die Hard, Predator, and The Hunt for Red October, had hired Pellicano to snoop on producer Charles Roven, whose hits include Batman Begins, Three Kings, and Scooby-Doo.

McTiernan and Roven were working together on the film Rollerball at the time and battling over creative control. The Los Angeles Times characterized both men as “strong-willed” individuals who had “numerous creative disagreements over the film.” But McTiernan wanted a tactical advantage in his dealings with Roven, so he hired Pellicano to listen in on the producer’s phone calls. Rollerball, which was released in 2002, was ultimately a box-office flop.

When FBI agents questioned McTiernan about his association with Pellicano, the director denied having hired the private eye to eavesdrop on Roven’s phone calls. But in fact, the director had used Pellicano’s services prior to this. McTiernan’s ex-wife, Donna Dubrow, told the Los Angeles Times that she had seen financial records indicating that starting in 1998, McTiernan “had paid Pellicano in the neighborhood of $100,000 during their protracted divorce.” According to court records, McTiernan had hired Pellicano to “harass and intimidate witnesses,” but Dubrow could not say for certain that Pellicano had wiretapped her phones on behalf of her ex-husband.

According to the Los Angeles Times, McTiernan also commissioned Pellicano to intimidate a witness in a manslaughter case. In 1993, Dubrow’s son, Ethan Dubrow, had been showing some friends a shotgun when it suddenly discharged and fatally wounded Adam Scott. Ethan Dubrow pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter, but in May 1998, Pellicano called a witness to the shooting, Suzonne Stirling, and accused her of obstructing justice in allowing Ethan Dubrow’s attorney to get her out of the country before she could testify. Stirling denied Pellicano’s accusation and demanded to know why he was bringing up Adam Scott’s death five years after it had happened. Pellicano’s response, if he gave one, has not been made public.

With McTiernan’s guilty plea, the Pellicano investigation had finally struck where Hollywood feared it would, the heart of the creative community. If a major director could get swept in it, who would be next?

The trial of Anthony Pellicano and six co-defendants is scheduled to begin in October 2006. Federal prosecutors are seeking to prove that Pellicano and his associates conducted illegal wiretaps and misused police databases for Pellicano’s clients. They believe that their case is strong, but four years after FBI agents confiscated roughly 1,300 audio files from Pellicano’s office, they have yet to break the encrypted code that protects them.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Kevin Lally laid out the situation at a hearing before U.S. District Judge Dale S. Fischer on June 12. The government has turned over 367 audio files to defense attorneys. Of all the files seized by the FBI, about 250 recordings were deemed irrelevant to any of the named defendants, and about 400 others are considered privileged communications between Pellicano and his lawyers and therefore not part of the case. More than 275 of the remaining files remain encrypted.

Defense attorneys were quick to complain that the prosecution was withholding evidence from them, reasoning that even if the material in those files were produced immediately, they wouldn’t have enough time to listen to them thoroughly before the October trial date.

Co-prosecutor Dale Saunders explained that the government has been hindered in producing this evidence by the sophistication of Pellicano’s encryption system. Saunders then glanced at Pellicano seated at the defense table. If the defense was “so desperate to get those files,” Saunders said, “the man with the password is sitting right there.”

Pellicano grinned.

Government hackers are currently working around the clock to break the code to those 275 audio files. Further indictments are expected as Hollywood holds its breath.

Abrams, Garry. “The Rise and Fall of Bert Fields.” Los Angeles Times. 7 May 2006.

Burrough, Bryan and John Connolly. “Talk of the Town.” Vanity Fair. June 2006: 88-105.

Carr, David. “A B-Movie Becomes a Blockbuster.” New York Times. 20 Feb. 2006.

Christensen, Kim. “Divorce, Pellicano-Style.” Los Angeles Times. 3 May 2006.

Eller, Claudia, Greg Kirkorian, and Kim Christensen. “Links Between Pellicano, Director Come Into Focus.” Los Angeles Times. 5 April 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. “Film Director Is Accused of Lie to FBI.” Los Angeles Times. 4 April 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “A Detective To the Stars Is Accused of Wiretaps.” New York Times. 7 Feb. 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “A Studio Boss and a Private Eye Star in a Bitter Hollywood Tale.” New York Times. 13 March 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “Broader Inquiry Examines Ovitz Ties to Detective.” New York Times. 15 Feb 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “Celebrity Lawyer in Talks About Wiretapping Evidence.” New York Times. 25 Feb. 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “Complex Maneuvering Over Evidence in Hollywood Wiretapping Scandal.” New York Times. 6 April 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “Detective’s Employer Knew About His Sleuthing Device.” New York Times. 12 Feb. 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “Evidence of Wiretaps Used in Suit.” New York Times. 24 March 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “F.B.I. Files Link Big Film Names to a Detective.” New York Times. 14 April 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “New Wiretapping Charges Are Set in Hollywood Case.” New York Times. 4 Feb. 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “Pellicano Case Moves Beyond Hollywood.” New York Times. 26 June 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allison Hope Weiner. “Reporter’s Lawyer Subpoena Ovitz in Hollywood Suit.” New York Times. 11 Feb. 2006.

Halbfinger, David M. and Allsion Hope Weiner. “Stars’ Lawyer Linked to Wiretapping Case.” New York Times. 26 April 2006.

Krikorian, Greg. “Many of Pellicano’s Recordings Still Secret.” Los Angeles Times. 13 June 2006.

Krikorian, Greg and Andrew Blankstein. “Filmmaker Says He Lied in FBI Probe.” Los Angeles Times. 18 April 2006.

Piller, Charles. “A Glimpse at Wiretap Devise Central to the Case.” Los Angeles Times. 18 Feb, 2006.

Weiner, Allison Hope. “Two Plead Not Guilty in Sleuth Case.” New York Times. 22 Feb. 2006.

Weiner Allison Hope. “An Unexpected Twist in the Celebrity Private Eye Case.” New York Times. 16 Feb. 2006.