Ruthann Aron: A Deadly Campaign — A Deadly Campaign — Crime Library

Ruthann Aron, 54, of Potomac, Maryland, knew exactly what she wanted and she wasn’t going to let anyone get in the way of her achieving her goals. Her career was testament to that fact. She worked her way up from waitressing at her father’s New York diner to becoming a wealthy and successful businesswoman and a member of the Montgomery County Planning Board. She was even planning on launching a new career as a court mediator.

Yet, despite all her success, Ruthann wasn’t completely satisfied. She had what she believed to be much more important work to do and, like always, she went after it with great gusto. She decided to enlist the help of someone with whom she had crossed paths years earlier to get the job done.

In June 1997, Ruthann ran into William H. Mossburg Jr. at a restaurant in the Courtyard by Marriott hotel in Rockville, Maryland. Ruthann met Mossburg four years earlier when she was active in real estate development and working for the county Planning Board. At the time, Mossburg “was knee deep in a long-running feud with the county over his family’s trash operations on the outer fringes of Rockville,” a waste facility that the county believed was being run as an illegal dump, Dan Beyers and Michael Abramowitz reported in The Washington Post. His repeated run-ins with the county government and his fervent anti-establishment stance made him seem like the best candidate for the particular job Ruthann had in mind. Their brief encounter led to a meeting that weekend at a Gaithersburg restaurant named J.J. Muldoon’s.

During lunch, Ruthann made a startling proposal. She told Mossburg that she wanted to have someone “eliminated,” although she didn’t reveal the target’s identity. To Mossburg’s amazement, Ruthann asked him if he could help her. Despite his attempts to talk her out of it, Ruthann insisted that she wanted the job done. She was convinced that he was just the person to do it, although she didn’t really know him personally.

Mossburg didn’t let on that he was horrified by Ruthann’s proposition and said he would think about it and get back to her. He then left the restaurant in a state of near panic, believing that he was being set up by Montgomery County in retribution for years of legal wrangling over his waste facility. In actuality, the county had nothing to do with Ruthann’s bizarre request. The reality was that she had a personal score to settle and was willing to stop at nothing to see it through. However, her plans wouldn’t turn out quite the way she hoped.

After his meeting with Ruthann, Mossburg went home and, after deliberating over what he should do next, he decided to contact the FBI. The federal agency immediately brushed him off, disbelieving his incredulous story. He then called Deputy State Attorney Robert Dean, whom he later met, and informed of Ruthann’s shocking request. Dean had — just three weeks earlier — eaten breakfast at a Rockville bagel shop with Ruthann, who was at the time seeking support for her campaign for the County Council Seat. It was hard to believe that Ruthann would do something so horrible, but he didn’t want to take any chances.

Dean immediately informed the Montgomery County Police Department, who interrogated Mossburg for several hours about his meeting with Ruthann. During the interview, Mossburg felt that the police had a hard time believing his story, and as they repeatedly questioned him, it appeared to him that the police might implicate him in the murder scheme. To his relief, they asked instead if he would serve as an informant for them, to which he agreed.

In order to collect evidence to substantiate his story, the police monitored a telephone conversation between Mossburg and Ruthann on June 4, 1997. Even though Ruthann didn’t come right out and say that she wanted someone murdered, the conversation did support Mossburg’s earlier statements that something devious was indeed in the works. Investigators had to work fast to get more evidence, which they hoped would lead to her arrest. One of the main questions they wanted answered was the identity of Ruthann’s intended target, so that they could protect the person before Ruthann got a chance to kill them herself.

During the course of their investigation, detectives quickly discovered that Ruthann’s plans involved having more people murdered. Before they could understand her motivation for ordering the heinous crimes, investigators had to unravel Ruthann’s complex character. What they discovered was surprising.

Ruthann was born to David and Frieda Greenzweig on October 24, 1942, in Brooklyn, New York. She was the first born of two children, the youngest being her brother Neil, several years her junior. During Ruthann’s youth, the family moved to Fallsburg, New York, a Catskill Mountain resort town, where her father owned and operated a traditional stainless-steel diner. As a child, Ruthann worked there with her brother, waiting tables and assisting with daily operations.

Ruthann proved to be a hard worker, which was not only evidenced by the long hours she put into the diner, but also by the tremendous amount of work she invested in school. She was a gifted student with high aspirations, excelling in science, as well as in other classes. The Washington Post’s Gregg Zoroya reported that she was “always at the top of her class,” which earned her entrance to Cornell University in the 1960s, where she majored in microbiology. Ruthann went on to obtain a master’s degree in education from New York University. During her studies, she met a charming and ambitious medical student named Barry Aron. The young couple fell in love and within a year they were married.

Unfortunately, problems began to surface early on within the marriage. One of the major difficulties they faced, which nearly ended their marriage, was Barry’s infidelity, specifically an affair he had four years into the marriage with a nurse, according to Katherine Shaver of The Washington Post. Despite their marital problems, the couple managed to keep their relationship intact. Soon after, they had their first child, Dana, born in 1970. Her birth was followed two years later by that of her brother, Josh, the couple’s last child.

During this time, Ruthann and Barry struggled financially. Ruthann worked as a teacher and researcher to earn enough money to support the family, while her husband worked his way through medical school to be a urologist. Barry eventually found work in the medical corps at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland, prompting the family to move to nearby Montgomery County in 1973. Three years later, Ruthann, then 33, went to law school at Catholic University. This time her husband financially supported the family with the income he made with his urology practice and work he conducted at the newly constructed Shady Grove Adventist Hospital, which opened in 1979.

Like her husband, Ruthann was on a mission to succeed. By 1980, after being admitted to the Maryland bar, she promptly began working for a zoning hearing examiner in Montgomery County, Charles Babington reported for The Washington Post. Ruthann was quoted in the article as having been “bitten by the bug of zoning and land use,” which led to her shifting political gears and turning her “full attention to real estate development in 1983.”

At that time, Ruthann worked with a series of partners, developing commercial and residential projects in and around Montgomery County. Zoroya reported that she was highly successful in the “male dominated world” she entered, completing seven projects in a ten-year period. As a result, the couple amassed significant wealth, living in a stately colonial-style home in Potomac, Maryland, an affluent suburb of Washington, D.C. However, some of the money they accumulated, estimated at about two million dollars, went to fund Ruthann’s legal bills, a result of business deals gone sour. Her legal problems would lead to a very public showdown that would negatively alter Ruthann’s future course and set in motion a series of potentially deadly events.

Ruthann Aron’s legal problems began in 1984, when two businessmen sued her company, Research Inc., for fraud and breach of contract. According to the men, the three went in on a project together to develop a Rockville shopping center, a business venture in which they claimed to have invested a great deal of money. Babington reported that Ruthann “sold the right to buy the shopping center for $200,000 and had kept the money herself rather than share it with them.” Ruthann insisted she did nothing wrong and the men who claimed to finance the project were actually never partners in the deal.

To her dismay, a Montgomery County civil jury returned a verdict of fraud and breach of contract, ordering Ruthann to pay close to $175,000 to the businessmen. Upon payment, Baltimore lawyer Arthur G. Kahn who represented the men “agreed to have the judge vacate the jury’s verdict, meaning the lawsuit’s final record would not reflect the judgment” against Ruthann, Babington stated in his article. Regardless, the judgment would later come back to haunt Ruthann and Kahn would become her nemesis.

In the meantime, other legal battles were brewing, including one that occurred that same year, involving a dispute over money between Ruthann and her partners concerning a development project. Like the previous lawsuit, Ruthann was accused of profiting from the sale of property but failing to split the money with one of her partners. Once again, she lost the lawsuit and paid out $175,000 in damages.

A third lawsuit was launched by Ruthann, who claimed that another partner with whom she previously worked duped her out of assets that she alleged belonged to her. The case went to trial and Ruthann lost again. The judge ordered her to pay her opponent’s court costs but according to Babington, she contested the ruling and eventually didn’t have to pay anything. It was a small victory, which would later be overshadowed by less successful courtroom battles.

Sarbanes

In the early 1990s, Ruthann once again shifted gears in her career, boldly venturing into the world of politics. After briefly serving as president of the West Montgomery County Citizen’s Association, Ruthann lobbied for a position on Montgomery County’s prestigious Planning Board in 1992. She was voted in on a narrow margin.

The Planning Board position involved, among other things, allocating millions of dollars towards the development of new real estate projects that were aimed at maintaining and improving the design of the community. The power and influence that came with the job was enticing. It likely had a great effect on Ruthann, propelling her to seek a more weighty position in the upper echelon of the United States government.

Tennessee, William E. Brock III

Initially, Ruthann ran for a Republican seat in the House of Delegates. However, she quickly changed her strategy and focused her attention on a U.S. Senate seat that had been occupied for three consecutive terms by Democrat Senator Paul Sarbanes. At the time, the Republican National Committee was looking for a female candidate to take his place and they set their eyes on Ruthann. Yet, before she could take on Sarbanes, she had to first defeat former Republican U.S.Senator fromTennessee, William E. Brock III, in the 1994 Republican primary. It would prove to be a vicious battle.

In August 1994, just months into her campaign, Ruthann’s father was found brutally murdered. The body of David Greenzweig, 77, was found face down in a pool of blood in the basement of his Fallsburg, New York home, which he had been renovating. His “skull had been crushed by a handyman’s pipe wrench and his head wrapped like a mummy’s in masking tape,” Karl Vick reported for The Washington Post. Investigators also discovered that several hundred dollars from his wallet and his 1984 Cadillac were stolen.

As soon as Ruthann learned of her father’s death, her campaign came to an abrupt stop. She immediately rushed to the small upstate town where she grew up to attend the funeral. Vick reported that during the ceremony, Ruthann “was the picture of poise—well dressed and polite.” It surprised some that she didn’t get involved in the investigation into her father’s death, which later revealed that a handyman and a drifter were responsible for the grisly murder.

Ruthann’s disinterest in the investigation likely stemmed from the fact that she and her father “hated each other,” Dominick Dunn reported in his Court TV series Power, Privilege and Justice. In fact, the feelings between the two were so hostile that Ruthann’s father specifically stipulated in his will that he wanted to leave “absolutely nothing” for his daughter who had “been cruel” to him and treated him “like a dog,” Paul Duggan and Manual Perez-Rivas of The Washington Post quoted Greenzweig’s lawyer Leon Greenberg as saying.

At the time of his death, it was unclear what events actually sparked the disdain Ruthann’s father felt for her. What was known was that since his divorce from Ruthann’s mother in 1982, contact between Ruthann and her father slowly diminished until it eventually ceased altogether. Her relationship with her brother Neil also distanced over time.

Conversely, Ruthann and her mother had a very good relationship. Vick reported that the mother and daughter shared an “uncommon closeness,” speaking on the phone “as many as a half dozen times a day.” Ruthann’s mother would be her primary source of social support throughout most of her life and she would help Ruthann through some of her darker days that were yet to come.

After a week in Fallsburg, Ruthann returned to Maryland, using her father’s murder as a platform to support her arguments for a tougher stance against crime. She also resumed her attack against Brock, to the point that she even interrupted him at media events and called him a flat out liar. Initially, Brock ignored the biting remarks from his rival but his patience wouldn’t last very long.

In September, Brock finally decided that he couldn’t sit back any longer and let Ruthann sabotage his campaign, so he fought back. He did so by telling audiences that Ruthann had previously been “convicted or found guilty by jury of fraud more than once,” Perez-Rivas and Jon Jeter reported for The Washington Post. The malicious remarks, implying that she had a criminal record, proved disastrous for Ruthann even though they were not entirely true.

Actually, she was never convicted in her previous court battles, but by then it didn’t matter anymore. Ruthann’s campaign was crippled beyond repair by Brock’s comments, resulting in her losing the primary race. Vick stated in his article “that there was nothing unusual about Brock’s counterattack” but what was unusual, said Tony Marsh, a veteran Republican consultant handling Ruthann’s media strategy, “was her reaction to it. It was all out of proportion…she sort of lost control.”

Taking Brock’s attack as personal, she immediately launched back by filing a slander suit against him. It was a historic move because “no losing federal candidate was ever before known to have gotten the winner into court over words spoken in a campaign,” Vick reported.

The move was, in essence, political suicide, destroying her chances of winning future campaigns. But at the time Ruthann was more interested in getting even than getting ahead.

During the 1996 trial in Annapolis, many testified, including Brock, Alexandria lawyer John E. Harrison, who represented a client in a 1990 lawsuit against Ruthann, and Arthur G. Kahn, who represented plaintiffs in a 1984 case against her. During his testimony, Kahn discussed how Ruthann defrauded his former clients and how the jury agreed that she acted inappropriately. Vick reported that a juror, Harmon Bullard, found Kahn’s testimony most memorable because he could almost see “the hate between the two in his voice and testimony.” It was considered a crucial “turning point” in the trial, eventually leading to another legal defeat for Ruthann.

However, in May 1997, a Maryland appeals court ruled that Ruthann had the right to a new trial because she was not allowed to review a juror’s notes of the proceedings, which allegedly influenced other jurors. But Ruthann would never have the opportunity to have a new trial. She would be too busy with other, more serious legal matters.

Despite the chance at a new trial, Ruthann felt embittered. She knew that Kahn would likely get the chance to testify again at a new trial, which she knew would probably destroy her case. There’s little doubt that she might have given up hope of winning because she had been defeated in almost every lawsuit she had ever faced. Her many legal losses, coupled with the fact that she failed at the primary race and, to make matters worse, that her relationship with her husband was crumbling, was likely all too much for Ruthann to bear. She had reached her breaking point, culminating in a ruthless murder-for-hire plan that investigators were just beginning to unravel. They just needed more evidence.

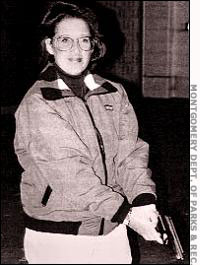

At the next available chance, Mossburg was wired with a microphone and asked to continue contact with Ruthann, feigning interest in helping her accomplish her vengeful scheme. At Ruthann’s request, their next meeting was at a local shooting range where she often practiced her favorite hobby, firing off her .38-caliber Detective Special revolver. It was one of many firearms she allegedly collected. To Mossburg’s surprise, at the time of their meeting, she was actually getting fitted for a new Beretta shotgun.

During their taped June 7th conversation, Mossburg told her that he knew of the ideal person to carry out the murder and he provided her with a number. Even though she often came across as paranoid for fear she might somehow get caught, revenge eclipsed her feelings of consternation, leading her to take the great risk of calling the unknown assassin who, unbeknownst to her was undercover police officer, Detective Terry Ryan.

The next day, Ruthann drove to a strip mall and placed a call at a pay phone to Ryan, who posed as a hit man. During a monitored conversation, Ryan agreed to Ruthann’s wishes of carrying out a murder for $10,000, which would be paid after Ruthann saw the victim’s name in the obituary of the newspaper. To be sure that he understood who he was supposed to murder, she carefully spelled out the intended target’s name, “K-A-H-N,” first name “Arthur.”

In the days that followed, investigators collected up to fifteen tapes of conversations between Ruthann and Mossburg, and her and Ryan. What was astounding was that during one of the conversations with Ryan, Ruthann suddenly added another name to the top of the murder list: her husband of 30 years — Barry Aron. She agreed to pay yet another $10,000 cash after seeing his name in the obituaries. During the phone call she was adamant about one thing: she wanted the murder to look like an accident.

Fearing that Ruthann might take matters into her own hands, investigators wanted to close the ring around her. They immediately moved into action with their plan to get the last bit of evidence necessary to close the case. That evidence entailed providing proof that she was actually willing to go through with plans for their intended murders.

As requested by undercover Detective Ryan, Ruthann made a down payment of $500 for the slayings. The money was put into an envelope, inscribed with the bogus company name “Universal Systems,” and delivered to the front desk of a Gaithersburg Marriot hotel. To prevent detection she wore a big white hat, a trench coat and sunglasses, not thinking for a moment that she might appear suspicious wearing fall-type apparel on a hot June day.

Moments after making the drop, Ruthann ditched her disguise and made her way to a scheduled golf game with members of the Planning Board. She had no idea that her every movement was being monitored by the police. That June 9th, Ruthann enjoyed golfing with her colleagues, discussing her new campaign for an at-large seat on the Montgomery County Council. However, she left the game early in order to make a phone call after she received a page from Detective Ryan.

When Ruthann called him, Ryan asked once again if she was sure whether she wanted to go through with their plan. She didn’t hesitate a moment and gave the all clear to carry out the slayings. It was the moment investigators were waiting for.

As the police monitored Ruthann during the call, they were surprised that she didn’t exhibit the slightest apprehension after just having ordered the murder of her husband. They knew that she needed to be stopped immediately. While walking from the phone to her red SUV, the police moved in on Ruthann and arrested her for two counts of solicitation to murder. While she was being whisked away to the police station for questioning, investigators immediately began gathering more evidence, beginning with a search of her vehicle. In it they found a red wig, a stolen Virginia license plate and lawn mower components (two mufflers) often used by criminals to make silencers for guns.

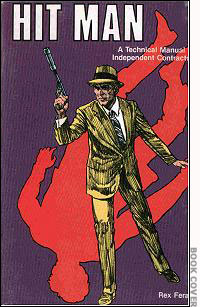

During a search of her home, investigators found, on Ruthann’s home computer, links to Paladin Press’s website that sold sinister how-to books, one of the most popular titles being Hit Man: A Technical Manual for Independent Contractors. A sales receipt from the company was also discovered at her home that included the titles, How to Make a Disposable Silencer and The Hayduke Silencer Book: Quick and Dirty Homemade Silencers, plus a book on disguises, all allegedly sent to a mailbox Aron rented under the name ‘A. Andrus,'” Vick reported. In Ruthann’s bedroom investigators made another startling discovery :a suspected “hit list,” including the names of Barry Aron, Arthur Kahn and “Alexandria lawyer John E. Harrison who represented a client in a lawsuit against her and who also testified for Brock in the defamation case,” Duggan and Perez-Rivas reported in The Washington Post. Furthermore, officers confiscated from her room an assault rifle, as well as other firearms belonging to Ruthann, but took several months to find her .38 caliber Colt revolver and 9mm pistol that were hidden away in a gym bag and storage box in her bedroom closet.

Investigators also uncovered a small prescription vial containing a white powdery substance, discovered in the pocket of a jacket hanging in Ruthann’s closet. Tests revealed that the powdery substance was actually a deadly drug cocktail. Investigators speculated about the drug concoction and whether Ruthann was planning to use it for suicidal purposes or to poison someone. Vick reported that the discovery might explain another book detectives found, entitled Final Exit, in Ruthann’s possession. The book was “a how-to manual published by the Hemlock Society, which promotes euthanasia and suicide.” Allegedly, Barry had given it to Ruthann after an earlier suicide attempt when she found out about one of his affairs.

What investigators didn’t know at the time but would later find out was that earlier that year, Ruthann made a batch of chili, Barry’s favorite dish. While eating the meal he immediately realized that it tasted unusual. Barry then slipped off into a deep sleep, only to awaken fourteen hours later with a severe headache. Even though forensic tests revealed no signs of the drug mixture in Barry’s system, it did not prevent Ruthann from getting an additional charge of attempted murder. She later pleaded not guilty, likely knowing that the charge would be difficult to prove because of a lack of evidence.

Conversely, the two counts of solicitation to murder against Ruthann, which carried a maximum sentence of up to life in prison, were charges backed up with an enormous amount of evidence. On the advice from her lawyers, Ruthann made a bold move and chose the most uncommon and controversial course of action, which was to plead “not criminally responsible.” It was the state of Maryland’s version of the insanity plea.

Ruthann’s arrest stunned the political establishment, sending shockwaves that reverberated throughout the nation’s capital and the outlying areas. Few could imagine that someone as successful and wealthy as Ruthann could be capable of planning anyone’s murder, let alone that of her husband. Moreover, many were equally as shocked that her legal team was pursing an insanity defense, one that is rarely successful.

Montgomery County lawyer Robert H. Metz, who had close political ties with Ruthann, was astonished by her plea and was quoted in Vick’s article as saying that she acted “absolutely normal,” which was why “everyone was so surprised.” Vick reported that most people who knew her agreed that she “was functioning at a high level in the weeks before her arrest, tending to her part-time position on the Planning Board while doing the spadework for a run at an at-large County Council seat — after a planned switch to the Democratic Party.” Many who were closely following Ruthann’s case were convinced that the evidence against Ruthann was just too strong and that her plea of “not criminally responsible” was a shoddy ploy at trying to escape life in prison. Few believed her lawyers could actually pull it off.

Helfand, left, and Erik Bolog

Ruthann’s attorneys, referred to by Shaver as “Montgomery County’s version of the ‘dream team,'” included Rockville, Maryland criminal defense lawyer Barry Helfand, Washington, D.C. lawyer Erik D. Bolog and Rockville lawyer Judy Catterton, a “former prosecutor who helped re-write Maryland’s insanity law in the early 1990’s.” Their job was to convince a jury, mostly with the help of mental health care specialists that their client had a long history of mental illness that impaired her judgment and functioning, thus rendering her not accountable for her criminal behavior. At the request of her lawyers, Montgomery County District Court Judge Louis Harrington allowed Ruthann to be temporarily released from her jail cell to visit the psychiatric ward of Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, to begin her evaluation. It would prove to be a daunting task that would require countless tests and interviews to determine her mental state over the years and leading up to her current condition.

Ruthann spent about a month at Suburban Hospital before she was transferred to Clifton T. Perkins Hospital Center in Jessup, Maryland, a state-run psychiatric facility, where she was evaluated for a further two months. Between the two facilities, Ruthann’s diagnosis widely varied, ranging from minor to severe mental health issues, including Borderline Personality Disorder, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Depression and Bi-polar Disorder. Despite the varying diagnoses, state doctors eventually determined that she was competent enough to stand trial and was well aware of her actions at the time she was methodically planning the elimination of her husband and Kahn.

Attorneys for the prosecution, headed by Deputy State’s Attorney I. Matthew Campbell, compiled an impressive amount of medical data, as well as physical evidence, in their case against Ruthann. They hoped that the fifteen tapes of Ruthann openly soliciting the murders of Barry Aron and Arthur Kahn would be the most persuasive evidence that might help them win their case. It all depended on the ten women and two men that made up the jury in one of the more riveting political trials in U.S. history.

Ruthann’s murders-for-hire trial, presided over by Judge Paul A. McGuckian, began in the last week of February 1998 at the Montgomery County Circuit Court in Rockville, Maryland. Shaver and Ruane reported that the 120 potential witnesses lined up to testify “read like a Who’s Who of Montgomery County politics,” including such propel as “County Executive Douglas M. Duncan, State’s Attorney Robert L. Dean, several Montgomery County planning commissioners with whom she served on the Planning Board, Montgomery Sheriff Raymond M. Knight and two General Assembly delegates.” Ruthann’s main supporter, her mother Frieda Singer, was also present and was on the list of those expected to testify.

On February 26th, the jury heard opening arguments, followed by prosecution testimony from several police investigators and Mossburg. During his testimony, Mossburg told the jury how Ruthann tried to employ him to carry out the sinister task she had in mind. He said that she complained about how a lawyer deceived her and that she believed in “an eye for an eye.” Mossburg also talked in detail about his collaboration with investigators and the taped conversations between him and the accused that led to her arrest. To support his statements, the prosecution played the tapes for the jury. Hearing Ruthann coldly discuss hiring a hit man to kill two people undoubtedly influenced the jury and caused some damage to the defense’s case. The question was, how much?

The defense team launched back, claiming that they never refuted the fact that Ruthann tried to hire a hit man but claimed that the authorities “entrapped her” and “encouraged her to go further than she intended,” Shaver reported. Defense attorneys then made a surprising revelation, suggesting that Ruthann’s vulnerable mental state that led her to commit the crimes was caused by childhood sexual abuse by her father and a brain injury known as temporal lobe encephalopathy, which is believed to affect one’s impulse control. It was the first time the shocking information was disclosed, and it provided some insight into her hatred for her father and desire to kill her husband.

The second week into the trial, Barry took the stand and answered questions relevant to what he knew about Ruthann and her father’s relationship. He told jurors that throughout the marriage he was never made aware of sexual abuse by Ruthann’s father. However, he did mention that her father was indeed a “bullying man” who “yelled and screamed a lot,” Shaver quoted him as saying. Regardless, Ruthann visited him and her mother regularly during the earlier years of their marriage, it was further reported.

Barry also talked about his turbulent 31-year-long relationship with Ruthann, which he likened to a “rollercoaster.” He admitted having an affair, which was the source of many of the arguments the couple had. At one point, Barry was confronted with a note he had written to Ruthann, which said, “I am going to have an affair if I want to, and if you don’t like it you can shoot yourself in the head.” He claimed to have no memory of writing the note, but said that if he had written it, he likely did so during one of the many arguments they had, Shaver reported. The note was testament to the fact that their marital problems had spun dangerously out of control well before Ruthann tried to harm her husband, and it had gotten progressively worse as time had worn on.

Barry also told the jury about one of the more volatile arguments they had in the mid-1990’s, which led to his pushing her so hard that she fell backwards through a set of doors. The argument was purportedly over money in his wallet. Barry claimed that the impact of her hitting her head, as a result of the push, caused her to briefly pass out, although he thought she was faking losing consciousness. When she came to, Ruthann went into her bedroom, grabbed her gun and threatened to shoot Barry if he came near her. It was unclear if Ruthann’s diagnosis of temporal lobe encephalopathy stemmed from the head injuries she sustained from the force of the fall. What was clear was that Ruthann had had enough and was filled with so much rage that she was capable of killing.

Barry further testified about the weeks leading up to Ruthann’s arrest and how she exhibited an “uncomfortable calm,” that was out of character for her, Shaver reported. Even when he threatened divorce during that time, it elicited little response from her. He commented that she would normally fly into rages at such comments. Despite the many arguments they had in their turbulent marriage, he never really believed she would plan to have him killed. He told the court during cross-examination by defense attorneys that it was hard to imagine that “Ruthann could do anything as horrible as what has happened without being mentally ill”…,” further saying that “the thought that she did it without being mentally ill is really impossible for me to bear.” Shaver reported.

During the course of the trial, jurors heard the testimony of various witnesses, many of whom included mental health specialists who spoke of Ruthann’s mental problems. One of the first to take the stand was Ruthann’s former psychiatrist, Dr. Nathan Billig, who treated her between 1974 and 1978 in Washington. Billig testified that when he treated Ruthann, she exhibited symptoms of Borderline Personality Disorder, a serious mental illness characterized by difficulty controlling emotions and impulses, inappropriate anger, interpersonal relationship problems, black and white thinking (or splitting), poor self-image, suicidal threats and fear of abandonment.

Billig said that Ruthann also exhibited intense rage against her father during therapy sessions. He said that she “hated” him and even considered “murdering him,” Shaver reported. He believed that the rage she felt for her father was transferred to her husband Barry and to Kahn, resulting in their being targeted for murder. Interestingly, when asked if Ruthann ever broached the subject of sexual abuse, he exclaimed that she never mentioned it in therapy, although it was “possible” he molested her, it was further reported.

Dr Alan Brody, who treated Ruthann between 1989 and 1993, was the second psychiatrist called to the stand. Like Billig, he claimed that Ruthann never mentioned sexual abuse by her father during earlier therapeutic sessions. Yet, she did mention it to him for the first time shortly after her arrest when she broke down under stress and regressed into a ‘primitive state,’ Shaver quoted him as saying. Brody testified that Ruthann likely suffered from Borderline Personality Disorder, although he diagnosed her years earlier with Dysthymic Disorder, a depressive mood disorder.

Other mental health experts, testifying for the defense, followed in line with Brody and Billig’s testimony, including that of neurologist Dr. Lawrence Kline, who found that Ruthann suffered Temporal Lobe Encephalopathy after her physical argument with Barry, as well as Bipolar Disorder and Depersonalization Disorder. His testimony was followed by psychologist Dr. Sallyann Amdur Sack, who diagnosed Ruthann with PTSD.

Testimony from Ruthann’s mother on March 12th provided the jury with some insight as to why Ruthann was so psychologically unstable. Frieda Singer testified that her daughter suffered immensely as a child, tearfully blaming herself for not being able to protect her from her “brutal” husband. Singer told jurors that when Ruthann was young, the family was extremely poor and were forced to temporarily live in a barn without plumbing or electricity. She claimed that her husband “brutalized her frequently” and “had no sense of family,” and that she once caught him fondling Ruthann when she was 8 or 9 years-old, Valentine reported.

Singer suggested to the court that Ruthann was not only maltreated by her father but also by her husband Barry who cheated on her during the marriage. She said that her daughter was so distraught that she attempted suicide on two separate occasions, once on Mother’s Day, Valentine reported. She further suggested that during one of her suicide attempts, Barry responded cruelly by buying her the book Final Exit by Derek Humphry, a manual that promotes suicide. Valentine quoted Singer as saying, “I don’t know how she got where she is with all that happened to her.”

Even though the mental health specialists that testified for the defense presented compelling evidence supporting Ruthann’s mental instability, other experts claimed that her mental problems didn’t necessarily mean she wasn’t criminally responsible for her crimes. Professor Barry Gordon, a behavioral neurologist at John Hopkins University, testified that Ruthann’s attention to detail during the planning of the murders was proof of her ability to function at a high level, throwing into question the defense’s argument that she was functionally impaired.

Gordon’s testimony was followed by that of a psychiatrist for the state’s Clifton T. Perkins Hospital Center, who suggested that Ruthann’s “mental illness and any mild brain damage were insufficient to fit the definition of ‘not criminally responsible’ under Maryland law,” Shaver reported. The state psychiatrist, Dr. Christiane Tellefsen, claimed that people affected by a serious mental illness would often “sound confused” or “rambling.” The fact was that Ruthann did not exhibit such characteristics, evidence that further weakened the defense’s case.

After the testimony of several other psychologists who squabbled over Ruthann’s interpretation of ink blot tests, the battle of the mental health experts in the courtroom finally ceased. After fifteen days of testimony, the jury began deliberations. Their job was to sort out all the psychiatric terms and medical data in order to determine whether Ruthann was in fact criminally responsible for hiring a hit man to murder her husband and Kahn. The deliberation process would not go as smoothly as hoped.

The suspense was almost too much. Those following the case anxiously waited for five intense days for the jury to arrive at a verdict until finally the shocking news came out. Juror Shawn D. Walker, 39, an instructor at a Rockville school for the mentally disabled, hung the jury when she sympathized with Ruthann’s insanity defense, Shaver reported.

News of the mistrial spread through the political establishment like wildfire. State Attorney Robert L. Dean immediately responded by telling reporters that the prosecution was going to seek a retrial as soon as possible. Defense Attorney Barry Helfand expressed his delight at the outcome but worried whether Ruthann was emotionally capable of going through another trial. Shaver quoted him as saying, “This has been very gut-wrenching for her. She was very, very upset and very, very scared.”

Regardless, Ruthann was free on bond, preparing for the upcoming trial scheduled for July, 1998. This time, she would exchange her defense team for a new lawyer, former Montgomery County prosecutor Teresa Whalen. According to The Washington Post, Whalen worked for the State’s Attorney’s Office, but was fired by Robert L. Dean in 1997 after allegedly ending a sexual relationship with him. At the time she took on Ruthann’s case, Whalen was in the process of launching her own lawsuit against her former boss.

In the meantime, Barry Aron filed a lawsuit against his estranged wife. According to Arlo Wagner, reporting for The Washington Post, the suit contended that Barry “suffered emotional and physical distress as a result of his wife’s attempts to poison his dinner and then hire a hit man to kill him, and he continues to be fearful for his life.” The $7.5 million lawsuit was filed in June to meet the statute of limitations.

In July 1998, Ruthann returned to court for her retrial with considerably much less fanfare than her previous trial. The public had grown weary of the case because the most interesting testimony had already been revealed. There was little new evidence to present.

During the retrial, the defense team decided to try a new approach. Their strategy centered on presenting less confusing testimony concerning Ruthann’s mental health and greater focus on the entrapment argument, attempting to prove that Ruthann was “goaded” into hiring a hit man. The prosecution also revised their strategy, this time following a more “streamlined” approach. However, they decided to keep the evidence that convinced eleven of the twelve jurors several months earlier.

In the middle of the retrial, Ruthann hired attorney Barry N. Nace to represent her in a $25 million countersuit against her husband. Ruthann alleged that Barry “committed medical malpractice and intentionally inflicted emotional distress” when he prescribed her a combination of sedatives without ever diagnosing her condition, Philip P. Pan reported for The Washington Post. Nace claimed that the drugs “exacerbated” Ruthann’s mental problems and caused a “psychotic break,” leading to the contract on her husband’s and Kahn’s lives, it was further reported. However, the case would never be tried.

On July 31, 1998, Ruthann made a surprise plea of no contest, abruptly ending her retrial. Consequently, Ruthann was immediately ordered to jail to await sentencing. Four months later, she stood before Circuit Court Judge Vincent E. Ferretti, who ordered her to serve three years in the county jail. During her sentencing, Ruthann said that in actuality she did “crack up,” although it was no excuse “for the most unconscionable and most unmentionable thing a human being can do,” Shaver reported. She then broke into tears and apologized to her two children before reciting a Jewish prayer of forgiveness. She was then led away to jail.

After two years of hard time, Ruthann was released on probation in 2001. Shaver reported that “her entire record, including her conviction on two counts of solicitation to commit murder, had been expunged.” Ruthann, who was divorced from Barry during her jail term, set out after her release to start a new life in New York City. She moved there to be closer to her son Josh, who was killed several months later in the September 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center.

In 2005, Ruthann made the news again when a Maryland court reviewed whether she was sticking to her parole agreement. She was under scrutiny by the court because she was found to have a Florida driver’s license and address, which she obtained under a different name. According to her parole, Ruthann was only “allowed to leave New York to visit her daughter in California or her mother in Florida but only for 30 days and only with her probation officer’s permission,” which she did not have, Shaver reported. Nonetheless, there was no clear cut evidence that she had violated parole.

To date, Ruthann’s whereabouts are unknown, which is a frightening thought for some. Mossburg and Kahn have both expressed concern that Ruthann might return to seek vengeance against them, Dunn reported. As Mossburg was quoted saying in the interview, “She’s capable of anything.”

Babington, Charles (May 20, 1994). Aron’s record cuts two ways.The Washington Post.

Beyers, Dan and Abramowitz, Michael (June 11, 1997). Aron Informant Known to Police. The Washington Post.

Duggan, Paul and Perez-Rivas, Manual (June 15, 1997). Aron grew to be a political scrapper. The Washington Post.

Dunn, Dominick (2002). Dominick Dunn’s Power, Privilege and Justice: Deadly Campaign. Aired on Court TV.

Perez-Rivas, Manual and Jeter, Jon (June 10, 1997). Ex-Candidate accused in hitman case. The Washington Post

Shaver, Katherine (August 7, 1998). Ruthann, Barry Aron Head to Divorce Court; $4.5 Million in Assets at Stake in Battle. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine (February 23, 1998). Aron’s murder-for-hire trial pits top local legal teams. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine and Ruane, Michael E. (February 26, 1998). Jury selected for Ruthann Aron Trial. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine (March 3, 1998). Jury hears Aron soliciting hit man. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine (March 6, 1998). Husband says Aron is mentally ill. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine (March 7, 1998). Psychiatrist recalls Aron’s rage in 1970s. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine (March 19, 1998). Aron tapes used to rebut defense. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine (March 31, 1998). Five-week Aron case ends in mistrial. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine (November 23, 1998). Aron gets three years in murder plot. The Washington Post.

Shaver, Katherine (January 20, 2005). Md. Court is asked to review Aron’s actions. The Washington Post.

Valentine, Paul W. (March 13, 1998). Aron’s Mother Describes Abusive Home. The Washington Post.

Vick, Karl (February 15, 1998). The mystery of Ruthann Aron. The Washington Post.

Vick, Karl (August 12, 1997). Exam could bolster planned insanity plea. The Washington Post.

Wagner, Arlo (June 9, 1998). Aron lawyers attack suit by husband. The Washington Post.

Washington Post (May 16, 1998). Aron gets rid of 3 defense lawyers.

Zoroya, Gregg (August 27, 1994). Aron takes time off after father slain. The Washington Post.

Zoroya, Gregg (September 3, 1994). Aron’s tough image no false façade. The Washington Post.