Movies Made Me Murder — Screamers — Crime Library

The movie, Scream, directed by Wes Craven, featured a character wearing an elongated white face mask with hollow eyes and a black cowl, popular among Trick-or-Treaters and for Halloween parties. Aired in 1996, the film satirized a collection of past slasher movies, offering the plot of a teenage girl targeted by a maniacal killer (Ghostface) who must learn her town’s secrets to save herself. But even satires can trigger unbalanced minds to mimicry. It’s all in the images.

Even as Scream spawned two top-grossing sequels, it also inspired crimes. For three or four years after its release, a number of teenagers were inspired to murder: a boy and his cousin in Los Angeles obsessed with the film murdered his mother by stabbing her 45 times; a man wearing the mask shot and killed a woman in Florida; a boy in France killed his parents while acting as Ghostface; and in England, a pair of boys repeatedly stabbed a third one, claiming the film had prompted them to do it.

Daniel Gill, 14, and Robert Fuller, 15, from North Yorkshire, were found guilty on October 22, 1999 of the attempted murder of Ashley Murray and were sentence to detention in a juvenile facility for six years. They stabbed Murray eighteen times and left him to die, but a day and a half later a man walking his dog found him, and he recovered.

Just before the attack, the boys had watched Scream at the home of a drug dealer, who had shown them occultic items and weapons, and allegedly told them that the gods wanted Murray to die. Their defense was that this influence had blurred the line between fantasy and reality, as well as the line between right and wrong. Drawings of Ghostface and pictures of knives turned up in one boy’s schoolbooks, according to the BBC.

But they were friends of Murray’s, and even he conceded that the film might have directed their behavior. That was the statement he gave to police. They had lured him to an isolated spot, he said, and then Gill stabbed him repeatedly in the cheek and head. Fuller held him and stabbed his arm. Only when Murray pretended to be dead did they leave, but he was too injured to find his way to a hospital.

Fuller accused Gill as the ringleader, and while Gill initially refused to admit his part he later said that the drug dealer had given him drugs and urged him to kill Murray. He had believed it was a supernatural command.

While it appears to be true that some people who immerse in horror imagery feel provoked to commit the same aggressive crimes they just viewed, it’s also true that there is no evidence of a causal factor, and millions of people watch such films without feeling instigated to act. Some people process external images into aggressive behavior, others might gain catharsis, and still others remain altogether unaffected. A few become horror film makers or novelists. It’s not easy to know just what effect a specific film might have. Whatever results, research shows that it has more to do with the viewer than the material viewed.

In the December 2006 issue of Scientific American Mind, Daniel Strueber, Monica Luek and Gerhard Roth cover the latest work from brain researchers devoted to the subject of violence and aggression. They focus largely on psychopaths who feel no empathy for their victims or regret afterward for what they have done. They plan and kill in a disconnected manner. It turns out that “violence never erupts from a single cause,” but instead derives from a combination of risk factors.

Debra Niehof, a neuroscientist, had already noted this with her book, The Biology of Violence, published in 1999, after she had studied twenty years’ worth of research. Specifically, she wanted to know whether violence was the result of genes or largely influenced by the environment. In her opinion, both biological and environmental factors are involved, and each modifies the other such that processing a situation toward a violent resolution is unique to each individual. In other words, a particular type of stimulation in a film is not going to provoke violence in every viewer. One person might react, while another might be completely unaffected by the very same exposure.

The way it works, says Niehoff, is that the brain keeps track of our experiences through chemical codes. When we have an interaction with a new person, we approach it with a neurochemical profile, which is influenced by attitudes that we’ve developed about whether or not the world is safe, whether people are trustworthy, and whether we can trust our instincts. However we feel about these things sets off certain emotional reactions and the chemistry of those feelings is translated into our responses. “Then that person reacts to us,” says Niehoff, “and our emotional response to their reaction also changes brain chemistry a little bit. So after every interaction, we update our neurochemical profile of the world.”

For causal associations, Strueber and his associates focus on the negative experiences a person might have. The risk factors included inherited tendencies, a traumatic childhood, and other types of negative exposures, all of which aggravate one another via interaction. Being male is one risk factor, as is having a violent role model and showing frontal cortex abnormalities that promote impulsivity. High-risk individuals might also develop a low frustration tolerance level and fail to learn social rules. In males, a higher testosterone level has been linked to aggression. (One study found this to be true of violent women as well.) In addition, head injuries of certain types seem to predispose certain people to violence.

Among the more interesting studies — albeit with low numbers and with only adult male subjects — Dr. Adrian Raine and his colleagues at the University of Southern California, compared 23 psychopaths who’d been caught vs. 13 psychopaths who remained at large. On the assumption that those who remained free were better planners, MRIs indicated that the “successful psychopaths” had a higher volume of gray matter in the frontal cortex than those who’d been caught. In addition, the unsuccessful psychopaths showed an asymmetrical hippocampus. Other researchers pinpoint dysfunctions of the amygdala as playing a part in a person’s capacity to feel empathy (or not). The balance of neurochemistry, too, has a role, which will be affected by a combination of one’s heredity and one’s environment.

It’s safe to say that in cultures that tolerate violent images and even encourage them, there will likely be a greater propensity among young people and the mentally disturbed to be influenced toward acting out what they see. If their options for dealing with conflict are limited to violence as a resolution, they will generally turn to violence themselves. Some researchers have estimated that by the time a child reaches the age of eighteen, he or she has seen around 100,000 violent images on television, in film or in videogames. It seems absurd to believe that such exposure will have little to no effect.

In The Copycat Effect, Loren Coleman indicates that any type of visual media that sensationalizes a crime can generate fallout in the form of mimicry. Similar incidents generally follow within a few weeks. We’ll get to the mimicry angle later. For now let’s return to these cases.

One of the movies mentioned most often in a murder defense in recent years has beenThe Matrix, released in 1999 and starring Keanu Reeves (with two sequels) as “Neo.” He finds himself in an alternate reality, aware that he once was “unconscious” in a computer-generated virtual reality and killers are chasing him. He must resort to fancy footwork and plenty of violence himself in order to save the world. All that he once believed has proven false as he’s designated the savoir and learns his secret super powers. What Neo does serves a higher purpose, which gives his violence noble flavor. But that’s a movie.

Or is it? Apparently, some murder defendants have come to believe they were in the matrix and that killing others was therefore justified.

Many people believe that Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, the 1999 Columbine High School killers, were inspired by it, although unlike some, they did not live to tell. At any rate, they did wear black trench coats like Neo.

One-half of the beltway Sniper team from 2002, Lee Boyd Malvo, was devoted to the movie. In jail he made many jottings, including a plea that people should free themselves from the Matrix. He told the FBI to watch the film, states Mark Shone in the Boston Globe, if they hoped to understand how his mind worked.

In San Francisco, Vadim Mieseges, 27, killed and dismembered his landlady, and in his defense he said that he’d been “sucked” into the Matrix. A Swedish exchange student, he confessed to skinning his victim and dumping her torso into a dumpster because he sensed “evil vibes” from her. Since he’d already been diagnosed with a mental illness, the case did not get to trial. His insanity plea was accepted.

In Ohio, Tonda Lynn Ansley also attacked her landlady on this premise, but was certain she had not really done so: it was only a dream. She had targeted three others as well, to free herself from their mind control. Her insanity plea, too, was accepted.

The Boston Globe ran a list of people in 2003 who had claimed that The Matrix had inspired them to kill. One case that turned up in Virginia is that of nineteen-year-old Joe Cook, who claimed he did not realize what he was doing when he dressed like Neo, grabbed his twelve-gauge shotgun (purchased because it resembled one in the movie), and shot both of his adoptive parents to death. Initially hoping to use an insanity defense, Cooke’s attorney put this into motion, but then stopped the process and entered Cooke’s guilty plea — his idea. He decided to take responsibility.

Yet it turned out from birth records that his biological parents had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. An assessment indicated that he could have been influenced by the idea that he was in an unreal world, and also been genetically primed to transform them into a sense of reality. In addition, his habit of playing violent video games for many hours every day had played a role, as did the fact that he’d been bullied as a child and had felt many things building inside until he just exploded. In the end, he received forty years in prison.

Other adolescents, too, have learned what it means to emerge from fantasy back to reality.

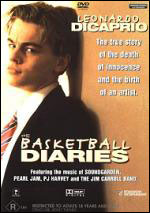

The Basketball Diaries is a 1995 film adaptation of Jim Carroll’s book by the same title about his immersion into drug addiction. As a member of a successful high school basketball squad, he must deal with a coach who takes inappropriate liberties and his own appetite for heroin. His mother’s anger over his activities drives him into the streets of New York, where he becomes a thief and whore to support his habit.

While the film was controversial for its graphic portrayals of drug addiction and prostitution, one scene in particular appeared to inspire several school shootings. It’s a dream sequence in which Jim (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) enters his school dressed in a black trench coat and shoots several students and teachers with a shotgun. His friends egg him on.

Not long after the film was released, on Feb 2, 1996, fourteen-year-old Barry Loukaitis dressed in a long coat entered his algebra class in Moses Lake, Washington. Concealed in his long duster were two pistols, seventy-eight rounds of ammunition, and a high-powered rifle. He pulled the rifle out and began to shoot, hitting Manuel Vela, 14, who later died. Another classmate fell with a bullet to his chest, and then Loukaitis shot his teacher in the back as she was writing a problem on the blackboard. A 13 year-old girl in the front row took the fourth bullet in her arm.

“This sure beats algebra, doesn’t it?” he reportedly said with a smile.

Then Loukaitis took hostages, allowing the wounded to be removed, but was stymied by a teacher who rushed him and put an end to the irrational siege. In all, three people died, and Loukaitis blamed “mood swings” and being bullied.

In his bedroom the police found a novel by Stephen King, Rage, that features a boy shooting his algebra class teacher and a video of The Basketball Diaries. In addition, Loukaitis said that he’d been inspired by a music video by Pearl Jam called “Jeremy,” which featured a similar scene of violence in a classroom, although the teenager who takes guns into the school kills himself along with his classmates.

Michael Carneal, another school shooter, looked to The Basketball Diaries as well for his inspiration. In 1997, after ruminating on “doing something big” for over a year, he killed three classmates in Paducah, Kentucky and wounded five others.

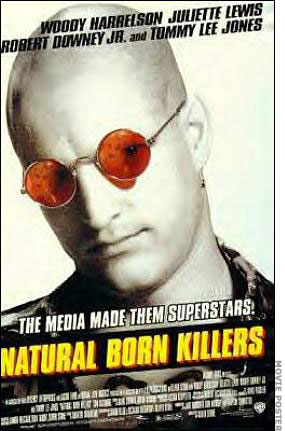

One other movie inspired Loukaitis: Natural Born Killers, and this one was cited as an influence by several of the kids who went to shoot up their schools in subsequent years. Another students who knew Loukaitis said that the shooter had thought it looked like fun to go on a murder spree like that.

Let’s look at the plot.

Mickey and Mallory Knox (Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis) are the two brutal killers in Oliver Stone’s 1994 release, Natural Born Killers. Intended as a statement about the level of violence tolerated by American society and the way criminals are turned into heroes, Stone used the one-time exploits of real-life spree killers Charles Starkweather and his girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate, as well as Bonnie and Clyde, to develop a couple of characters whose murderous exploits (over fifty victims) propel them into international stardom. A tabloid journalist follows them, promoting them and hoping to get an exclusive interview, to his peril.

The movie is filled with graphic images of violence and gore, as the two psychopathic lovebirds use murder and torture as an aphrodisiac. They claim that violence makes them feel alive. Thus, they equate murder with power, control, bravado, and status. Not only that, the killers, who look like heroes contrasted to abusive parents and corrupt justice systems, never have to pay for what they’ve done, although just about everyone else does. Including some viewers.

Kimveer Gill, who shot at people at Dawson College in Montreal in September 2006, killing one and wounding nineteen before killing himself, said this movie was one of his favorites, and Natural Born Killers was reportedly viewed by eighteen-year-old Sarah Edmondson and Benjamin Darras in 1995 before they went on their own crime spree.

Benjamin Darras

|

Sarah Edmondson

|

On March 5, they spent the evening together dropping LSD and repeatedly viewing the film. Taking a .38 revolver with them, they got in the car the next morning and took off across Oklahoma to Mississippi, where they killed a man at a cotton mill. Then they went to a convenience store in Louisiana, where they shot Patsy Byers in the head, leaving her paraplegic. Her husband filed a lawsuit against Edmondson and Darras, then added Time Warner, Oliver Stone, and others associated with making and distributing the film. They claimed that everyone associated with it should have realized it could have inspired murder. They also called it pornography.

The suit was dismissed against Stone and the production companies, but on appeal, was reinstated. The Louisiana State Supreme Court declined to review the decision, as did the U.S. Supreme Court. Finally, in March 2001, the wrongful death suit was dismissed against Stone and Time Warner, etc. because there was no evidence that they had intended to incite violence. The Court of Appeals upheld this ruling in 2002.

Other crimes listed by freedomforum.org that may have found some inspiration in NBK include:

- a 14-year-old Texas boy who decapitated a 13-year-old girl

- A gang who watched the film 19 times killed a truck driver in Georgia

- Michael Carneal’s slaughter of fellow students in Paducah, Kentucky

- Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold used the movie title’s initials as a code — “going NBK” when they felt it was time for violence.

Even before that, another psychotic film scene had possibly launched an even deadlier attack.

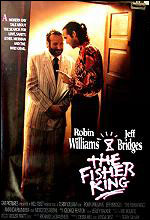

George Hennard had watched a documentary about James Huberty, a disgruntled man who’d shot at customers at a McDonald’s restaurant in San Ysidro, California on July 18, 1984, killing 21. He had also watched the Fisher King, a 1991 movie directed by Terry Gilliam and starring Jeff bridges and Robin Williams, in which a fan of a despondent shock rock talk radio host takes the man’s remarks seriously, goes to a restaurant, and opens fire, murdering numerous diners. The DJ takes a downhill turn and to redeem himself tries to assist a homeless man who lost his wife in the massacre.

Apparently the tale about Huberty mingled with the image of shooting into a restaurant, then exacerbated by Hennard’s anger. He decided to make a public statement as dramatic as Huberty’s. Hennard had a habit of talking in a way that made people think he was a bit crazy. He’d tell strangers such things as, “I want you to tell everyone that if they don’t quit messing around my house, something awful is going to happen.” He was upset about the recent hearings in which Anita Hill had accused judicial candidate Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment, and disliked any “female viper” who harassed men. Apparently he believed he’d had his share of that.

Having just turned 35 on October 15, 1991, the following day Hennard rammed his blue Ford pick-up through the plate glass window of Luby’s Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas. He hit an elderly man, and the patrons who ran to the victim’s aid initially believed that the whole thing was an accident. But then Hennard jumped among them with a Glock 17 semi-automatic and a Ruger P89 and began to shoot. Yelling that it was “payback day,” he snarled at diners to “take that!”

Stopping once to reload, he had enough clips of ammunition to spray the weapon many times across the room. Inexplicably, he allowed one women with a child to leave, although she was forced to abandon her dead mother. One person who escaped recalled later that Hennard had been smirking the whole time.

The police arrived and commanded Hennard to drop his gun, but he ignored them, turning his weapons on them. Two bullets hit him, forcing a retreat, and he took cover. Apparently he realized it was now over, so he put one pistol to his head and pulled the trigger, killing himself. When police went in, they found twenty-two people dead and twenty-three wounded. On Hennard’s body, according to Coleman, they found a ticket to The Fisher King.

While Hennard was a loner, he had no apparent reason to be so angry. He lived in a nice home and was fairly attractive. His father was a surgeon. He was not the typical man down on his luck. Yet he had made an appeal to be reinstated in the Merchant Marines, in which he had served for eight years, which had been denied six months before the incident. Someone who had served with him said he’d harbored a violent hatred toward his domineering mother, whom he regarded as a snake, and Hennard had an unfounded delusion that women were harassing him.

Although there is no record that he sought help or was assessed as mentally ill, his reputation for lashing out without provocation, as well as his extreme beliefs about women, could be considered paranoia-induced psychosis. Unlike the characters in the film, he seemed to have no particular reason to act out that day. It wasn’t like our next story, in which a man was seeking the attention of a character from a film.

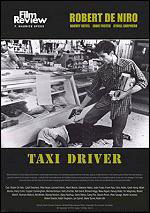

A number of high-profile crimes were influenced by plots or scenes in films, but one that affected the legal system across the country, and was even shown in court, was Taxi Driver, released in 1976.

John Hinkley, Junior was obsessed with the film, particularly a young actress who starred in it named Jodie Foster. He read the novel and watched the film over and over, looking to it as a guide for his actions. Robert DeNiro starred as Travis Bickle, a disturbed taxi driver who decides to assassinate a presidential candidate as a way to attract the attention of a female political worker that he has his eye on. However, he fails at this and becomes involved with a young prostitute name Iris (Jodie Foster). He rescues her by killing three people and thus, with criminal violence, becomes her hero.

Hinkley, a failed songwriter with an imaginary girlfriend, was apparently impressed by all of this, and in his bid to win the attention of Jodie Foster (whom he’d already been stalking all the way to Yale), he stalked President Jimmy Carter for a while and then, after some psychiatric treatment for depression, set out to shoot Ronald Reagan, president who succeeded Carter. On March 30, 1981, outside the Washington D.C. Hilton Hotel, Hinkley emptied a revolver and managed to wound Reagan, along with three others, before he was wrestled to the ground and arrested. Foster was reportedly horrified.

At Hinkley’s insanity trial, in which he was charged with thirteen offenses, Dr. William Carpenter, Jr., described how Hinkley had strongly identified with Travis Bickle, dressing like him and imitating him in a variety of ways. He’d isolated himself and lived largely in his fantasy world, coming to believe that he was in fact Bickle.

The movie was shown to the jury to help them understand how Hinkley “became” this character, and Hinkley strained to get a good look at his hero. He sat rapt throughout the screening, although he apparently could not watch the scene in which Iris hugged her pimp — one of the people that Bickle later killed.

The trial lasted seven weeks. Found not guilty by reason of insanity in 1982, Hinkley was confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC. He continued to be obsessed with Foster for the next two decades. This verdict upset the American public, so the federal government, along with several states, revised their laws regarding insanity. Four states abolished it as a defense altogether.

Still, the U.S. was not the only place where killers took their cues from a movie. Let’s look at a young man in Scotland.

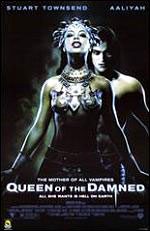

Allan Menzies, 22, was obsessed with the vampire film, The Queen of the Damned and he considered its principal character, the vampire Akasha, his “queen.” By his own count, he had watched the film at least 100 times, sometimes three times a day. In the process, he came to believe that Akasha actually appeared to him and ordered him to do things. So he killed, and his crime and trial were covered extensively by The Scotsman.

Akasha, played by the late actress Aaliyah, is depicted in The Queen of the Damned, based on Anne Rice’s novel of the same name, as the ultimate vampire progenitor. She’s a vicious blood hunter with no remorse. Beautiful and vibrant, with slender build and sexy clothing, she captured more than one teenage male’s fantasy.

In the novel, Akasha had been an ancient Egyptian queen whose jealousy of the powers of a pair of twin witches over a spirit led the spirit to infuse Akasha with its essence, which carried a powerful thirst for blood. As Akasha became a vampire and then transformed her husband and others, all vampires became connected to her. In the novel, she started killing mass numbers of humans to feed her pathological need, commanding her prince, Lestat, to do the same.

Thomas McKendrick, Menzies’s best friend, had introduced him to the film and he begged to borrow it. He was soon hooked. Akasha became real, as did other vampires, and he began to call himself “Leon.” Menzies believed that Akasha made regular visits to him and had made a deal to grant him immortality in exchange for killing people to deliver their souls. It wasn’t long before McKendrick disappeared, last seen when he visited the Menzies on December 11, 2002.

Menzies’ father came home that day and noticed spots of blood in various places around the house. That worried him, but Allan told him it had come from cutting himself on a can.

On January 4, McKendrick’s clothing was found in a bag on the moors, so two days later the police searched the Menzies’ home. After they talked with Allan, he took an overdose of drugs and ended up in the hospital. On January 18, 2003, McKendrick’s remains were found in a shallow grave. The pathology report indicated that he’d been stabbed 42 times with a large knife in the face, head, and body, and bludgeoned over the head six times with a hammer-like instrument. The attack, the pathologist commented, had been carried out for a prolonged period of time.

Menzies said that he had decided to sell his soul to be born into another life, another form. He tried to plead guilty to culpable homicide on the grounds of diminished capacity, but the Crown rejected it and ordered him to stand trial in October 2003. He cast the blame on an alter ego, developed under the influence of the film, and said he wished he had never seen it. He told the High Court that on December 11 McKendrick had made the fatal error of insulting Akasha. Menzies had “snapped,” bludgeoning him and stabbing him to death. He then drank McKendrick’s blood and offered this death to Akasha.

“I could never get the thought of being a vampire out of my mind,” he said. “To put it bluntly, after I had seen the tape so many times, I wanted to go out and murder people.” He believed that imbibing the blood of his victim made him a vampire and sealed his pact with Akasha.

The jury deliberated for an hour and a half and returned a unanimous verdict that Menzies was guilty of murder. The judge gave him a minimum sentence of 18 years.

Another killer had a similar experience, but his orders came from above — or at least through a movie screen.

In West Germany, the “Beast of the Black Forest” was prowling around in 1959. In a dark alley in Karlsruhe, the body of a woman was discovered. She had been raped and her throat slit with a razor. On the same night, another woman reported being accosted by a man who’d run off when a taxi drove by. The police could find no clues from either incident to assist in arresting someone.

Yet several more dead women turned up over the next few months, as well as a series of complaints about sexual assaults. One woman, a student named Dagmar Klinek, had been thrown off a train after being raped in an empty railway car. She was further assaulted outside on the ground, and stabbed to death. Still, there were no clues.

Then during the summer of 1960 in Hornberg, a young man picked up a suit he had previously ordered and left his briefcase in the tailor’s shop while he went on an errand. (In another account, he changed into the new suit and left his other clothing behind in the shop.) The tailor noticed something odd about the briefcase so he opened it and found a modified rifle with a sawed-off barrel. Since this was clearly for a crime, and possibly to rib him, he alerted the police, who awaited the man’s return. When he walked into the shop, he was arrested. He gave his name as Heinrich Pommerencke, age 23.

Under further interrogation, he admitted to robberies committed in another town. Just to test him, investigators told him they had found bloodstains on the suit he’d left at the shop, and it had matched the blood of several murder victims in the Black Forest area. Pommerencke fell for the ruse, admitting that he’d raped and killed several women (some accounts say he admitted to ten). He was obsessed with sex, he said, and had been since he was quite young. But it was a movie that had inspired him to act out.

He explained how he had watched a showing of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, seen the licentious women dancing around the golden calf, and decided that he “would have to kill.” It was his mission. Among other felony charges, he was convicted of four murders, a dozen attempted murders, and twenty-one rapes. He was also suspected in six other murders, and despite his supposed lunacy, he received six life terms.

While it makes some sense to find culpability in overtly violent films, we wouldn’t expect that a film like The Ten Commandments would inspire lust murders. Yet, apparently, it did. We can list a few other movies that have been thus associated as well.

A number of other movies have been spotlighted in murder cases, and for each one, it’s a similar story, so we offer a brief list:

American History X (1998) — Ed Norton stars as an American Neo-Nazi who murders a black man during a rage, but the film takes a clear stand against racial violence of this sort. Nevertheless, that scene allegedly provoked three Neo-Nazi teenagers in Germany to bludgeon the death a stuttering classmate who was Jewish. He was forced to bite a pig trough, supposedly because he was considered sub-human, while one of the boys re-enacted the brutal “curb stomping” scene.

American Psycho — a controversial film starring Christian Bale about a supremely narcissistic psychopath who kills to relieve pressure from competition and disappointment, it was roundly condemned by critics for its gratuitous violence. Michael Hernandez spent the evening before he killed his friend, Jaime Gough, reading reviews of this film as well as looking at gory drawings and reading about baby killers in Australia. He was obsessed with death, says the Sun-Sentinel in Miami. He then stabbed Gough 40 times in a restroom at school.

Nightmare on Elm Street — Donald Gonzales, 25, was convicted of killing four people on a three-day stabbing rampage in southern England in 2004. He also tried but failed to kill two others. He compared his murders to the film, Halloween, and said he aspired to be Freddy Krueger, the fictional killer with knife-like fingers in the Nightmare series.

Memories of Murder, directed by Bong Jun-ho, was released in South Korea in 2003 and it depicted a decade-long series of unsolved murders in Hwaseong during the 1980s. The killer is organized and careful, leaving little evidence behind. He seemed to have a preference for victims wearing red and white, or perhaps just red.

A year later in Seoul, it seemed that the film was being re-enacted in another series of murders, and the killer turned out to be Yoo Young-Cheol. But in his rooms were three other movies as well: Public Enemy, Very Bad Things and Normal Life. The first featured a serial killer who preys on the wealthy. Yoo was convicted of twenty murders, mostly women and the elderly, but he claimed that he had hoped to kill 100. He received the death penalty.

Child’s Play — Four people in England claimed this as an influence in the murder of Suzanne Capper, 16, in 1992. They had injected her with drugs, tortured her with pliers and set fire to her house. All the while, they spouted lines from the movie.

Hiroyuki Tsuchida, 22, used a baseball bat to beat his mother to death in June 2003 in Japan. He was stopped before he could do the same thing to the rest of his family. When questioned he claimed the anime series, Neon Genesis Evangelion, had given him the idea that humans should be eliminated, so he’d decided to start with his own family. His reasoning was that once he could do that, he could more easily go kill others.

Another murderer seemingly influenced by Japanese pornography and anime was Tsutomu Miyazaki, a.k.a., “the Little Girl Murderer.” As a boy, Miyazaki was physically challenged and he thus developed into a loner who thrived on fantasy and comic books. Highly sexed, he moved on to child pornography and reportedly collected thousands of videos, as well as Japanese anime, or live action films based on cartoons. Apparently, he was influenced by horror films, especially the series of “Guinea Pig” films, and there is speculation that the second one in that series became a model for one of his murders.

Miyazaki grabbed his first victim, four-year-old Mari Konno, on August 22, 1988, taking her into a park, photographing her, and strangling her. He then undressed her and left her nude body behind while he took her clothing with him — which he also photographed. The 26-year-old man got away with it so he plotted another kidnapping and by October, he was at it again.

Driving around, he spotted Masami Yoshizawa, 7, walking by herself. It was easy to persuade the child to get into his car, and he returned to a spot close to his first murder — in fact, where that child’s undiscovered bones still lay. This time, after strangling his victim, Miyazaki had sexual contact, and he once again walked away with her clothing.

On December 12, Miyazaki murdered another four-year-old girl, Erika Namba. Again, he talked her into getting in his car. He photographed her before killing and dumping her, and was very nearly caught, but managed to get away. He kept a low profile for the next few months before taking his last victim.

In the meantime, Erika’s corpse was found and witnesses described the car they had seen in the area. The police also learned that each of the families of the three girls had received strange phone calls: always, the caller remained silent. They also received gruesome postcards with letters cut from magazines to form words like “cold” and “death.” Mari’s parents also found a box left on their doorstep that contained such items as photographs of their missing daughter’s clothing, teeth, and charred bone fragments. Following this was a confession that Mari had been murdered.

The police learned that the camera used for the photos was a tool common to printers, and indeed, Miyazaki worked in that trade. Investigators were getting closer, but did not identify him not before he’d struck again.

On June 6, he grabbed Ayako Nomoto, 5, from a park after he’d taken photographs of her. This body he took home to videotape. Clearly, he was feeling bolder. Then he dismembered the corpse, consumed some flesh, and dumped the remains in a cemetery. While the corpse was found and quickly identified, Miyazaki remained free. That is, until he made a mistake.

In July 1989, he approached two sisters and lured one away. The other ran home to get help. Their father stopped Miyazaki in the act of photographing the child’s genitals and the police arrived as he ran to his car. Now caught, he offered a grim confession of killing the four children. A team of psychologist examined him, and found him responsible for his actions, although other examiners disagreed.

In the end, Miyazaki was found to have multiple personality disorder and schizophrenia, but was nevertheless sane, and he was given a death sentence. That sentence was upheld early in 2006, and he was executed June 17, 2008.

While experts disagree as to just how much films can influence a killer, research in biology makes the idea at least plausible.

Recent research in molecular biology indicates that as an evolutionary strategy, we may actually be programmed to mimic others. Sandra Blakeslee wrote about it for the New York Times. Apparently, researchers first noticed the phenomenon about fifteen years ago, in Italy. Wires were implanted in the brain of a monkey that monitored its movements when it manipulated an object, and a graduate student noticed that its brain reacted even when the monkey failed to move. The stimulus: watching someone else’s behavior — in this case, the student was lifting an ice cream cone to his mouth.

Giacomo Rizzolatti, a neuroscientist at the University of Parma, led the research in trying to determine what was occurring in the brain when the monkey (as well as human beings) observed others in specific behaviors. It seems that the same brain cells fired during observational behavior as during the act itself. Rizzolatti identified this class of cells as “mirror neurons.” By that, he meant that certain cells in the brain start processing when someone sees or hears an action that its own body can perform. The research was published in 1996.

However, more recently, research indicates that mirror neurons in humans are both intelligent and flexible. In fact, Blakeslee continues, humans have “multiple mirror systems that specialize in carrying out and understanding not just the actions of others but their intentions, the social meaning of their behavior and their emotions.” These neurons grasp the implications of the behavior they process via direct simulation. The person fully experiences another person’s behavior, rather than just contemplating it. This is at the heart of how children learn and why certain experiences are shared archetypally across cultures. People respond to what others model if it’s behavior common to that species. It may also explain why media violence influences certain people.

A study published in 2006 in Media Psychology indicated that mirror neurons were activated in children who watched violent television programs, and the prediction was that they would be more likely than others who did not watch to act more aggressively afterward.

It’s been found, however, that the more active the mirror neurons, the more empathy we feel. It may be the case, then, that children with “broken” or less active mirror neurons who also watch violent programs might behave aggressively because they don’t have the inhibiting experience that comes with empathy. But this connection is merely suggestive; it has not yet been studied scientifically.

Mirror neurons show up in several areas of the human brain. They activate in the face of actions that are linked to intentions, with different neurons firing for different parts of the process. They simulate the action as if the observer is actually performing it, which is how the person understands the action and what motivated it; there’s a sort of “template” for it in the brain. This affects the degree of empathy and language acquisition, as well as the ability to predict and anticipate. Yet certain brain circuits also inhibit the person from acting it out.

“Mirror neurons provide a powerful biological foundation for the evolution of culture,” says Dr. Patricia Greenfield, a developmental psychologist from UCLA. It remains to be seen how they will figure into research on violence and aggression.

Some movies, it seems, are so resonant that they trigger violence both toward oneself and others. One movie is notable for this.

The movie most often documented for its apparent inspiration for suicide is the award-winning The Deer Hunter, released in 1978 and starring Robert DeNiro, Meryl Streep, Christopher Walken, and John Voight. About three friends from Pennsylvania, Michael, Nick, and Steven, who enlist to fight in the war in Vietnam, the tale follows them as the Viet Cong torture them with a game of Russian roulette. Nick ends up so traumatized by his experience that he remains in Vietnam, making money by playing this same suicide game voluntarily. Ultimately, he kills himself.

Researcher Loren Coleman documents a number of suicides reportedly inspired by this film, evidenced by the way they copied the famous scene with Nick re-enacting his torture. In addition, Coleman cites other research about how the movie’s screenings in specific theaters, video rentals, or showings on television correlate with a rash of suicides.

Children who imitated the Russian roulette scene were likely just curious, but the older teens tended to be depressed or attempting some form of bravado. One man who re-enacted the scene in 1979 was a police officer. Many of the victims shot themselves in front of other people, usually friends or relatives. They often stated their influence from the film.

For example, a 1980 article in the New Orleans-based newspaper, the Times-Picayune, described how twenty-three-year-old Mickey Culpepper said to a friend, “Look. I’m going to play Deer Hunter” before shooting himself in the head with a .38.

Even worse, on October 8, 1980, a man was kidnapped near the World Trade Center and tortured by men intending to rob him; they re-enacted the Viet Cong torture scene.

The movie-related suicides occurred in other countries as well, documented in the Philippines, Finland, Lebanon, and other places, and even a Secret Service Agent apparently shot himself while viewing an HBO showing of the film. He survived.

Often, these incidents occurred while drinking or in a show of macho, but some were accidents result from someone just attempting to demonstrate something about the scene. But one incident was clear a murder: a prison guard in Rhode Island shot a prisoner while they discussed the scene and he reportedly tried to get other guards to play the game with him as well. So whether it’s violence against oneself or toward others, this movie clearly has had an influence.

It stands to reason that violent imagery will affect certain people in a way that inspires them to act out. From the story that affects them, they acquire a frame and guidelines, and sometimes even interpret the film as a license to kill. Not everyone will be thus affected, but among those who are, it’s safe to say there is such a thing as a “Copycat Effect” when the portrayal of violence grips a person so firmly that he or she decides follow the details of that specific template. Has the movie made him kill? No, but has it given him ideas and methods — even victims? We can see that such things have occurred and are likely to continue to occur.

In July 2007, a girl who participated in a triple homicide was convicted in Canada. Due to her age, Canadian media sources observed the Youth Criminal Justice Act and declined to reveal her name, but it has turned up in many international reports.

On April 23, 2006, in a town in southeastern Alberta called Medicine Hat, the parents and younger brother of Jasmine Richardson were discovered murdered in their home. A six-year-old friend came to the house early on Sunday afternoon, saw a body through the window, and alerted his mother, who called the authorities.

Police arrived and discovered three victims. Debra Richardson, 48, lay at the foot of the basement stairs, according to the Ottawa Citizen, covered in blood and stabbed 12 times. Her husband, Marc, was stabbed twice as many times, all over his face and torso, including his crotch. He’d bled out so much there was little left in his body, but from the spatters all over the TV room it was clear he had put up a tremendous fight. Eight-year-old Jacob was found in his bed, with his throat cut.

Detectives sent for the forensic unit to process the scene, and they brought dogs to go through the home and grounds. A white truck sat in the driveway with a smashed window, and another truck belonging to the family was found off the property. Items in the home indicated that there was a twelve-year-old daughter, Jasmine, who was missing. Police did not know if she had been abducted, so a country-wide warrant was issued for her.

Friends of Jasmine’s twenty-three-year-old boyfriend, Jeremy Allen Steinke, pointed authorities to a town in Saskatchewan, and they found Jasmine alive and with Steinke. He was an unemployed high school dropout, considered the unofficial leader of a group of Goth-punks. The two were arrested without incident and returned to Medicine Hat. After a hearing, Jasmine was sent to the Calgary Young Offenders Centre to await a trial. Within days, she had penned an apology letter to her family, admitting she had taken part in their slaughter. She wrote that she wished she could “take it all back” because now she “had no one.” She said her brother was killed because he was too sensitive to survive without her parents. She herself had choked him to make him unconscious.

Supposedly, this all occurred because the seventh-grade girl had reacted badly to being grounded for dating Steinke behind her parents’ backs. They told her she could no longer see him. Yet Jasmine had already agreed to marry Steinke and she was determined to be with him. She urged him to help her get rid of them.

A romantic bond was not all this couple shared: they had a fixation on Goth culture and Steinke even claimed to be a 300-year-old werewolf. Both had posts on a Web site known as VampireFreaks.com, and Steinke reportedly wore a vial of blood around his neck. Jasmine referred to herself on another site as “runawaydevil”. They shared an appreciation for razor blades, serial killers, vampires, and blood. They would soon learn that murder was not fantasy.

During the 2007 trial, covered by reporters from around Canada, some facts about Jasmine came out that indicated her state of mind. Not only did she and her boyfriend ascribe to the darker side of Goth culture, with a fixation on death and imaginary monsters, but they had watched the film Natural Born Killers.

Oliver Stone produced this 1994 film, which is engorged with gratuitous violence. A killing couple, Mickey (Woody Harrelson) and Mallory (Juliette Lewis), were based on spree killers Charles Starkweather and his girlfriend. Throughout the film they commit some 52 murders, including massacres with multiple victims. They start with the slaughter of Mallory’s abusive parents, one by drowning the other by burning, but spare the younger brother. One can see how an angry couple who embrace death culture and find parents an annoying hindrance might see in this film an affirmation of their bid for freedom and a violent solution.

While Jasmine’s apology letter was not read to the jury, deemed to have been gained via improper interrogation protocol, jurors did see a drawing found in Jasmine’s locker that depicted four stick figures. The middle-sized figure throws gasoline on the other three with a smile, lights them ablaze, and then runs to a vehicle labeled “Jeremy’s truck.” In addition, the two had exchanged letters after their arrest that indicated they wished they had run away together. There was no indication in these communications that Jasmine was remorseful or an unwilling accomplice. She also had stolen her mother’s ATM card that night, got money, and had sex with her lover — all pointing to a callous attitude. (Even her apology letter was largely self-pitying.)

Jasmine’s attorney, Tim Foster, accepted the idea that Jasmine might have engaged in discussions about killing her parents, but said she did not mean that she would literally do it. The scenario he painted was that Steinke had gotten high on cocaine, watched the violent movie, and undertook to rescue Jasmine, as “Mickey” had done for “Mallory. ” The idea was his alone, as was the act. Thus, Jasmine, too, was a victim.

She took the stand in her own defense and affirmed that her boyfriend was the killer. She cried when asked about choking and stabbing her brother and said that Steinke had made her do it, as her brother begged for his life. She had a knife in her hand, she said, for self-defense, but Steinke had taken it and slit her brother’s throat.

While the prosecutor conceded that Jasmine did not engage in the act of murder, she had persuaded and encouraged Steinke to do it, telling him which window would be unlocked for entering the home on Saturday night. She also willingly fled with him. Thus, she was eligible for a murder conviction. He urged the jury to remember her part.

On July 9, 2007, after the jury deliberated just over four hours, Jasmine was convicted of three counts of first-degree murder. She began to weep, according to the Edmonton Sun. Under Canadian law, she cannot receive an adult sentence, so she faced a maximum of six years in prison and four of probation. Steinke faces trial for murder next year; he has not yet entered a plea.

Jasmine Richardson is the youngest person to be convicted of multiple murder in Canadian history. For that matter, she’s the youngest in North American history.

Mentioned earlier in this article, the case of Donald Gonzalez has recently yielded more details. That’s because on August 9, 2007, he killed himself in England’s Broadmoor Hospital, and he managed it in a strange way.

Gonzalez was only 24 when he was convicted of the murders of four people and the attempted murders of two others during the course of a three-day frenzy of drugs and violence in Sussex and North London in September 2004. Gonzalez apparently wanted to see what it would be like to be Freddy Krueger, the monster from the classic slasher film, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and just start randomly attacking people. He stabbed his victims several times, some on the streets and others in their homes. His goal was to kill ten, which he believed would ensure that people remembered him forever. He hoped to be known as a famous serial killer, the way people thought of Freddy Kruger.

Wes Craven directed the American horror movie, which was released in 1984 to immediate success. It spawned a number of gruesome sequels and a comic book series, all of which featured the demented Freddy with his razor sharp claws. Set in a fictional town in Ohio, a girl named Tina has a nightmare about a man with a badly scarred face, and wearing a glove with sharp knives attached, stalking her. He slashes at her and she awakens but finds four rips in her nightgown where the monster had reached her. In her next dream state, she’s caught and killed, and she doesn’t wake up because she is actually dead. Her boyfriend is pinned as the perpetrator. The nightmare then infects a female friend of the victim, and when sleep therapy fails to alleviate it, a story emerges that the nightmare vision is the vengeful projection of a dead man, killed by the parents of children he molested.

According to critics, the story line challenges the boundaries between dream life and reality, so it might well have appealed to a person like Gonzalez, diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, or the inability to distinguish delusions and reality. Reportedly just months before his rampage, he had begged doctors to lock him up. Two days before the first murder, he ran naked into the streets, leaving a jumble of knives strewn about the kitchen, and his mother called for help. Yet, a story from Times Online indicates that he had set out to malinger a mental illness so that if he was stopped before achieving his goal, he’d be free in eight to ten years to continue.

In fact, in school Gonzales had been an accomplished actor. He had boasted to classmates that he would be famous one day. His hobby had been knife throwing and his favorite words were “murder, kill, death.” He suffered from coordination disorders and the inability to write coherently, which frustrated him. He was also a chronic bedwetter, as reported in the Scotsman. While he was intelligent and well spoken, he was disruptive and shunned by other students. He aimed to show them who he was.

In the high-security facility after his sentencing, Gonzales was considered one of the most dangerous patients, capable of extreme and unprovoked aggression. Since he’d once chewed through the veins and arteries on his arms, which required emergency transfusions, he was on a suicide watch.

His victims included an elderly couple, an elderly woman, and a middle-aged man. The two men who survived his knife-wielding attacks had been around 60.

Gonzalez, 26, was found in his cell on the morning of August 9, according to the UK’s The Sun, with his wrists slashed open. Apparently had had shattered a CD or CD box and used the sharp edges to do the job.

One source, who asked to remain anonymous, stated that “not many people will mourn his passing,” as he was difficult at best. He had even laughed in court over a letter of his read by the prosecutor to prove the disdain he held for his victims. The Argus quoted relatives of the deceased as finding relief in his suicide. A daughter of one victim hoped Gonzalez had died a “slow and painful death.” While death didn’t hinder Freddy Krueger, it will probably stop the young man labeled by some as the Knife Nut.

Blakeslee, Sandra. “Cells that Read Minds,” The New York Times, January 10, 2006.

Coleman, Loren. The Copycat Effect. New York: Pocket, 2004.

Deutsch, Linda. “Movie Obsessed Youths Convicted,” AP, July 1, 1999.

“Taxi Driver: Its Influence on John Hinkley Junior.”

International Movie Database Web site.

“I want to be a Famous Serial Killer,” Reuters, March 16, 2006.

Linedecker, Clifford. Babyface Killers. NY: St. Martin’s, 1999.

Niehoff, Debra. The Biology of Violence. New York: Free Press, 1999.

“Oliver Stone and Natural Born Killers Timeline. www.freedomforum.org.

“Police: ‘Scream’ Mask Suspect Had Serial Killer Literature,” www.local6.com, May 3, 2006.

Popyk, Lisa. “Blood in the School Yard,” Cincinnati Post, November 7, 1998.

Ramsland, Katherine. The Human Predator: A Historical Chronicle of Serial Murder and Forensic Investigation. Berkley 2005.

Schone, Mark. “The Matrix Defense,” The Boston Globe. November 9, 2003.

“‘Scream’ Attackers given Six Years,” BBC News, October 22, 1999.

Strueber, Daniel, Monica Luek and Gerhard Roth. “The Violent Brain,” Scientific American Mind, December 2006/January 2007, pp. 20-27.

“Teens Commit Movie Murder,” News24.com, May 26, 2003.

“Were Movies Yoo Young-chul’s Murder Textbook?” Digital Chosun, 2003.

Whipple, Charlene. The Silencing of the Lambs, www.charlest.whipple.net.