The Insanity Defense — ‘You Must Die!’ — Crime Library

“If you commit a big crime then you are crazy, and the more heinous the crime, the crazier you must be. Therefore you are not responsible, and nothing is your fault” Peggy Noonan, U.S. writer, newscaster.

(CORBIS)

Congressman Daniel Sickles saw the man walking in front of his house. The man, whose name was Phillip Barton Key, was a member of Washington D.C.’s social elite and the son of Francis Scott Key, author of The Star Spangled Banner. Sickles watched as Key attempted to call up to a second story window where Sickles’ wife slept. Sickles became enraged because he had known for several weeks that Key was sleeping with his wife. And worse, his friends and neighbors knew it too. Consumed by rage, he grabbed two handguns from his bedroom and ran out into the street where several pedestrians were walking. He ran up to Key screaming: “You must die! You must die!” Without provocation, he fired several shots at Key, striking him in the leg and thigh. The men engaged in a hand-to-hand struggle in full view of the White House where President James Buchanan (1856-1860) may have watched the drama unfold from his office window. Sickles managed to fire several more shots. Key fell back against a fence and pled for his life: “Please don’t kill me!” Sickles pointed a handgun at the victim’s chest and fired point blank at the helpless man. Key staggered away and died a few minutes later. There were at least twelve people who witnessed the killing. It was 2:00 p.m. on Sunday, February 27, 1859. Congressman Daniel Sickles (D.-NY) was arrested a short time later at the home of a friend and charged with murder. When he appeared in court to face a charge of 1st degree murder, his attorney said that Sickles could not be held responsible because he was driven insane by the knowledge his wife was sleeping with Phillip Key.

Daniel Sickles was a Union Army general who fought for several years in the Civil War. In the following years, he became Ambassador to Spain, the County Sheriff for New York, re-elected to Congress in 1893 and later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. But today, Sickles is remembered mostly for being the U.S. Congressman arrested for murder and one of the first defendants in American history to utilize an insanity defense. After a sensational trial that became the talk of Washington D.C. for weeks during 1859, Sickles was acquitted of murder and walked out of court a free man.

Justice is a difficult concept isn’t it? If ten people were asked to supply a definition of justice, chances are, we would get ten different answers. It’s not hard to imagine the founding fathers centuries ago, laboring under candlelight, quill in hand, the memory of British repression fresh on their minds, agonizing over the proper way to address the issue of justice in the Bill of Rights. How to balance the authority of the state against the rights of the individual? How to ensure that the courts would maintain their integrity and honor in the dispensation of justice? They were genius these founders, true visionaries whose ideas and concepts expressed in the Constitution have managed to hold together a nation of unequaled diversity and complexity for over 200 years. Through hard times and good times, war and peace, the dream survived: a country where justice is paramount and people are born with rights that even a king can’t take away. We are an idealistic people, though we don’t like to admit it at times. That explains why there are few aspects of our society that so infuriate the average citizen as the notion of failed justice. And nowhere in our system is justice so challenged, manipulated and abused as when a killer pleads an insanity defense.

“The inmates are ghosts whose dreams have been murdered” Jill Johnston, U.S. journalist after she observed “patients” in New York’s mental ward at Bellevue Hospital.

Throughout medieval times in Western civilization, people who displayed any sign of mental illness were treated with fear, revulsion and often times, violence. The “treatment” of such people frequently consisted of simply locking them up in a dungeon and ignoring them. They were considered possessed by demons or the devil. Many were murdered or burned at the stake, victims of a misdirected religious fervor that claimed thousands of victims, especially during the Inquisition in 13th century Europe. Organized crusades against so-called “heretics” were formed by the Roman Papacy to persecute those of lesser faith. Soon, the Inquisition was used to severely punish political enemies, criminals and the mentally ill. In England, pressures on the ruling classes, forced them to deal with those who appeared “different” than others. A place was needed to treat and house the mentally retarded and others with mental afflictions that could not be explained. As a result, the Priory of St. Mary of Bethlehem Hospital in London opened its doors in 1247 Encarta 2000.

(TIMEPIX)

The hospital became the first institution for the mentally ill in the Western world when it began to house the insane exclusively in the early 1400s and it soon gained a reputation as a place of suffering and misery. The living conditions for the patients were horrendous. They were often chained to the wall and tortured under the premise that it was for their own good. There were no guidelines or procedures on how to deal with the mentally ill at that time. Sanitary measures were unknown. For the most part, patients were left screaming in the darkness alone, sometimes doused in cold water or spun around in rotating chairs. Soon, members of the London upper class began to tour the hospital for entertainment. They were charged a fee to enter inside the institution and stare at the unfortunate souls who acted so much different than themselves. The hospital, if it can be called that, later became notorious under its better-known name, Bedlam; a word in the English language that has become synonymous with chaos and confusion. During the 19th century when its popularity was at its highest, Bedlam entertained more tourists than Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London.

The insanity defense has its roots firmly embedded in centuries of legal tradition. As early as the 13th Century, the English Lord Bracton established the principle of mental deficiency in human behavior. He said that some people simply do not know what they are doing and act in a manner “as to be not far removed from the brute” (Menninger, 1968, p. 112). From that concept, “insanity” came to mean that a person lacks the awareness of what he or she is doing and therefore cannot form an intent to do wrong. Since there was no malice in the intent of his or her actions, then there could be no technical guilt. The standard for insanity in the courts was determined to be such that a “man must be totally deprived of his understanding and memory so as not to know what he is doing, no more than an infant, brute or a wild beast” (Melton, 1997, p. 190). This “wild beast” standard was the insanity requirement of England’s courts for over a hundred years and any defendant who attempted to use the defense had to prove he or she lacked the minimum understanding of a wild animal or infant. It wasn’t until 1843, when a man named Daniel M’Naghten committed a murder that would alter forever the history of jurisprudence in the Western world.

“Integrity has no need of rules“

Albert Camus (1913-1960) French philosopher and novelist.

In 1843, Daniel M’Naghten, a Scottish woodcutter, shot and killed Edward Drummond, secretary to England’s Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel in London. He acted under the belief that he was actually shooting the Prime Minister because M’Naghten believed there was a plot against him. When M’Naghten reached trial, his attorneys pleaded that he should be acquitted because he was obviously insane and did not understand what he was doing. M’Naghten was later acquitted of the crime. Later that same year, the House of Lords issued the following ruling:

“To establish a defense on the ground of insanity, it must clearly be proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was laboring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing was wrong” (Melton, 1997, p. 191).

This edict became know as the M’Naghten Rule and for over a century, this was the standard for the insanity defense. As for Daniel M’Naghten, after his acquittal, he was sent to Bedlam and other institutions where he languished in the shadow world of the insane for several decades until his death in 1863.

The late 19th century was a time when scientific ideas were rampant. This explosion of science was partly brought on by the publication in 1859 of one of the most influential books ever written, The Origin of Species by Charles Darwin. The Darwinian concepts of survival of the fittest, natural selection and hereditary traits revolutionized biological science and were applied to many other disciplines. Ideas were evolving rapidly during this era in every medical, scientific and psychological field. Things were changing quickly in the legal profession as well. Dedicated lawyers and judges searched for workable solutions to the controversies that plagued the nations courts. The confusing ideas about mental diseases and the complexities of the human mind did not lend themselves well to the rigid dimensions of codified law. A glaring example of that confusion was the murder trial of Charles Guiteau in 1881, assassin of President James Garfield.

(CORBIS)

Guiteau was an erratic individual who suffered from some type of mental disorder, most probably paranoia. He had delusions that he should be appointed as Ambassador to France because he wrote a speech for President Garfield which he imagined helped get Garfield elected in 1880. The speech, in fact, was never used but Guiteau became despondent and bitter over this “betrayal” and plotted to get revenge against Garfield. After stalking the President for almost a month, he managed to shoot Garfield in the back at a Washington D.C. train station. The President was not killed outright however. He suffered with great pain for almost 3 months before he finally died on the night of September 19, 1881.

(CORBIS)

Guiteau’s trial was a sensation, not only because of the nature of his crime but his unusual outbursts and behavior in court attracted widespread attention. Guiteau testified in his own behalf and stated: “I want to say right here in reference to protection, that the Deity himself will protect me, that He has used all these soldiers, and these experts, and this honorable court, and these counsel, to serve Him and protect me” (Knappman, 1994, p. 190). He went on to tell the court that he shot the President because God told him that Garfield was destroying the Republican party and he must die to save the Democratic party. But the prosecutor, U.S Attorney Wayne Davidge told the jurors: “It is very hard to conceive of the individual with any degree of intelligence at all, incapable of comprehending that the head of a great constitutional republic is not to be shot down like a dog” (Knappman, 1994, p. 190). Charles Guiteau was found guilty of murder on January 13, 1882. Upon hearing the verdict Guiteau jumped to his feet and screamed “You are all low, consummate jackasses!” (Knappman, 1994 p.190). After reciting an incoherent poem in a child’s voice on the gallows, Guiteau was hanged on June 30, 1882. Although there was a strong public sentiment to punish Giuteau, despite his severe mental problems, his case underlined the need for change on how the courts dealt with the issue of insanity.

“The good of the people is the greatest law”

Cicero, Roman philosopher (106-43 BC)

The insanity defense is a source of continuous disagreement among lawyers, clinicians and the general public. There is a very strong perception in America that defendants are abusing this defense to escape murder charges in the nation’s courts.

On March 30, 1981, John Hinckley shot president Ronald Reagan and several of his aides on live television. Virtually the entire world saw the shooting via endless replays over the next few weeks. There was little doubt who did the shooting and how. Ronald Reagan eventually recovered, though today, we know his wounds were a lot more serious than we realized then. Press Secretary James Brady suffered severe head wounds and was confined to a wheelchair as a result of his injuries. On May 4, 1982, after a seven-week trial, during which numerous psychiatrists testified on his behalf, Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI). He was sent to a mental hospital in Washington D.C., where he is still confined today. The outcome of the Hinckley case sent shockwaves throughout the nation’s courts. How could a man who shot the president in front of millions of people be found not guilty?

One of the cornerstones of the criminal justice system in America is the concept of mens rea, a Latin phrase that translates to “state of mind.” In order for a person to be held criminally liable in the courts, our system demands that that he or she must have criminal intent or awareness of the wrongfulness of the act. If a person is mentally ill and unable to tell the difference between right and wrong, for example, then he or she cannot be held criminally culpable in our society. That principle upholds the dignity of the court and ensures those without malicious intent, such as the mentally retarded, will not be unfairly punished. Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780), the British legal scholar, whose work was used as the foundation for English and American law for centuries wrote “idiots and lunatics are not chargeable for their own acts, if committed when under these incapacities” (Friedman, 1996, p. 143).

There are many false beliefs held by the public regarding the utilization of the insanity defense at criminal trials. The most widespread misperception is that NGRI pleas are commonly used by defense attorneys to benefit their clients. However, there is abundant research that proves conclusively that just the opposite is true. A study conducted in Wyoming in the early 1970s showed that the insanity defense was used in only .47% of all criminal cases (Melton, 1997, p. 187). In New Jersey, a review of 32,000 criminal cases in 1982 discovered that the defense was raised in only 52 cases, less than .2% of the total (American Psychological Association Report January 9, 1996). In New York City, the insanity defense, historically, is used less than 1 in 700 cases (American Psychological Association Report, January 9, 1996). Other studies indicate very similar findings. In almost every review on the insanity plea undertaken in America, the results are the same: this type of defense is used in the nation’s courts only on very rare occasions. One such occasion that dramatized the issue of insanity was the Long Island Railroad killings in 1993 when a disturbed man, named Colin Ferguson, became front-page news in media-rich New York City.

(AP)

It was December 7, 1993 when Colin Ferguson, 28, boarded a train in Long Island headed for New York City’s Grand Central Station. The railroad car was packed with commuters. As the train pulled into the Mermillion Avenue station, Ferguson pulled out a semi-automatic weapon and began firing at random inside the commuter car. Several minutes later, after some courageous passengers wrestled the madman to the floor, six people were dead and 19 others seriously wounded. When Ferguson was charged in criminal court, famed attorney William Kunstler and his assistant, Ron Kuby, agreed to represent him. Kunstler and Kuby decided to use something called the “black rage” defense. They presented to the court that Ferguson, after years of living in a racist and oppressive society, was so consumed with anger that he just couldn’t help killing white people. Ferguson, however, disagreed. He denied his role in the killing and said that he was framed by persons unknown.

(AP)

Ferguson later fired his attorneys and won the right to represent himself. The court ruled that he was competent and what followed was one of the strangest criminal trials New York had ever witnessed. It was a proceeding that angered many people and brought into the public arena once again, how the law deals with the issue of insanity. Ferguson was able to question many of the victims on the stand who actually saw him do the shooting but insisted he was innocent. He rambled on endlessly in open court accusing the police, the media and the American people of conspiring against him. Kuby later said that the proof of Ferguson’s insanity was that he wouldn’t plead insane. He was found guilty in February, 1993 and sentenced to life without parole. “He’s too crazy!” Kuby told the press (N.Y. Daily News, February 18, 1993).

Another misperception of the insanity defense is that NGRI pleas are always successful. But the reality is exactly the opposite. In the same Wyoming study mentioned previously, only one person, .99%, of those that used the defense, was acquitted. Data gathered in other studies show higher rates but considerably less than half of those who pled the insanity defense were successful. In Hawaii, between the years 1969 and 1976, less than 19% of those who pleaded insanity were acquitted (Melton, 1997, p. 188). In New Jersey during 1982, the figure was 30%. Researchers in California, Georgia, New York and Montana uncovered similar findings. Simply stated, John Hinckley was one of the very few defendants acquitted by reason of insanity. For decades, the criteria used to establish a legitimate insanity defense was very rigid. Sometimes the most bizarre behavior, even when committed in public, did not satisfy that standard. One case from the 1940s that illustrates that point was the violent and vicious tale of the “Mad Dog Espositos” in New York City.

“Never pray for justice, because you might get some“

Margaret Atwood, Canadian novelist.

On January 14, 1941, two brothers, Anthony, 35, and William Esposito, 28, held up a payroll carrier for a linen company located at 34th Street and 5th Avenue in Manhattan. They shot and killed the office manager of the firm without warning as he rode in an elevator. When the brothers reached the street, they were confronted by Police Officer Edward Maher. During a foot chase down 5th Avenue, a gunfight ensued which sent hundreds of pedestrians ducking for cover. The brave officer managed to bring down William with a shot to the leg. When the cop went to check on William, the wounded man suddenly turned over and shot Officer Maher several times, killing him instantly. Several other people were wounded in the on-going battle. Both brothers were captured after pedestrians and a passing cab driver subdued them.

When they reached trial in May of 1941, the Esposito brothers based their defense on insanity pleas. The death penalty was a very real threat during that period. Unlike today, defendants were sentenced to death routinely and often the sentences were carried out without delay. It was also common for several convicts to go to the chair for the same murder. In court, the Espositos began a campaign of bizarre behavior to convince the court they were insane. They banged their heads on the defense table until they bled. They made animal sounds and howled like wolves. They ate bits of paper and anything else that was in front of them. While the jury was present in the room, they barked like dogs and cried uncontrollably. They drooled on the table and walked into the courtroom like apes. The New York press called them “The Mad Dogs.” At the end of the trial, Judge John Fresci said that the laws should be enacted to keep people like the Espositos out of the courtroom. But even all their hysterics could not persuade the court they were anything but vicious criminals. On May 1, 1941, after a jury deliberated for just one minute, a trial record that still stands today, William and Anthony Esposito were found guilty of Murder in the 1st Degree and sentenced to die in Sing Sing’s electric chair. But the “Mad Dogs” still weren’t finished.

On May 7, 1941, the Espositos were transported to Sing Sing prison by New York City Police in a commuter train from Grand Central Station. When they arrived in the Village of Ossining, a local cab picked up the brothers and the police to take them over to the prison reception area. As the car approached the front gates, Anthony suddenly grabbed the steering wheel of the police unit and attempted to crash the car. A violent brawl erupted between the “Mad Dogs” and the police. Anthony viciously bit the hand of the driver as he tried to get control of the car. William tried to grab a detective’s holstered gun. The police pulled out their blackjacks and beat the brothers into submission. They were dragged out of the car cursing and screaming. William continued to fight even as he was prone on the sidewalk. He was beaten unconscious and both brothers were later carried into Sing Sing (McNulty, p.4). While on Death Row, the Espositos continued their campaign to convince authorities they were crazy. They moaned in their cells and spoke gibberish to the guards. For 10 months they engaged in hunger strikes and ultimately refused to eat any food whatsoever. Governor Herbert Lehman appointed a commission to investigate the matter. It was found that the Esposito family arrived in America from Italy in 1909. Two other brothers were already in prison and two sisters also had arrest records. Their father was an ex-con who had died years before. Their mother had been arrested several times and the children were raised to hate the cops and the law. Governor Lehman refused to grant clemency.

In the end, William and Anthony Esposito laid in their cots all day long, eating nothing and groaning throughout the day and night. Neither of the brothers weighed more than 80 pounds. On March 12, 1942, they were carried to the electric chair unconscious, already near death, and immediately executed. The “Mad Dog” Espositos were violent criminals whose behavior shocked the public. But never did their actions constitute legal insanity.

The Espositos suffered the ultimate penalty for their crime. But their attempt at hiding behind the insanity plea failed. For those that succeed, there is a public perception that a defendant walks out of the courtroom a free individual. Since such defendants are found “not guilty,” it may not be illogical to believe that they face no prison terms. But, again, that is rarely, if ever, the reality. Most states require that a defendant be committed to a mental institution for a period of at least one year. And the most severely disturbed inmates may never get out of the institution. The majority of states have no set limit on the amount of time convicted defendants may spend in confinement as long as they meet the criteria that sent them to the facility initially. A similar fate may await those ruled incompetent to stand trial. At the infamous Matteawan State Hospital for the Insane in New York, a census was taken of 1,062 patients in the year 1965. It was found that 208 were being held from 20 to an incredible 64 years (Maeder, 1985, p. 119). Some of those were never convicted of any crime whatsoever. Through a combination of antiquated laws, neglect and retribution, some prisoners spent their entire lives in institutions, far longer than they would have spent in jail had they actually been convicted of a criminal offense (Maeder, 1985, p. 118). But it simply seems to be part of the historical pattern of abandonment and fear that society has practiced against the mentally ill for centuries.

The M’Naghten Rule was not without criticism. Some scholars felt that the rule was too rigid and would not excuse anyone from criminal conduct except the most severely mentally ill. The law, many people felt, should be more flexible. In 1886, the Parsons v. Alabama (81 AL 577, So 854 1886 AL) decision established additional criteria for the insanity defense. The court decided that a person could utilize the insanity defense if he or she could prove that “by reason of duress of mental disease he had so far lost the power to choose between right and wrong, and to avoid doing the act in question, as that his free agency was at the time destroyed. “. It became know as the “Irresistible Impulse Test” or as an earlier court in England called it, the “policeman at the elbow test.” In other words, if the person would have committed the crime even if a policeman was standing next to him, then the act could be characterized as an irresistible impulse because no sane person would commit a criminal act in the presence of a law enforcement agent. But what exactly was an “irresistible impulse”? How is it measured and how can one tell if another could resist an impulse? Many in the legal profession felt that this rule would allow criminal defendants to escape guilty verdicts by fakery and manipulation of the courts.

Subsequent rulings in the nation’s courts like Sinclair v. State of Mississippi (132 So. 581 1931 MS) which declared that sanity is an essential element of mens rea, Washington State v. Strasburg (110 P. 1020 1910 WA) and Leland v. Oregon (343 US 790 1952 OR) interpreted and refined the M’Naghten Rule under varying circumstances. Then in 1954, a Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., presided over by Judge David Bazelon, heard the Durham case and transformed the insanity landscape once again.

The Durham v. United States (214 F.2d 862) decision in 1954 widened the scope of psychological assessment of defendants and opened the door for an avalanche of expert psychiatric testimony. In the Durham case, the court ruled that a person could not be held criminally responsible if his act was the “product of a mental disease or defect” (Rowe, 1984, p. 319). The courts now had new, ambiguous words to deal with: “product” and “mental defect.” Later, the phrase “diminished capacity” also began to enter into the nations’ courts. The idea that a person who commits a criminal act was acting under a lesser capacity of understanding than was acceptable took hold.

The American Law Institute (A.L.I.) established a Model Penal Code in 1970 that was adopted by a number of states, eager to resolve the conflicts brought on by increasing frequency of the insanity defense. The A.L.I. model stated that a defendant is not responsible for a criminal offense if “at the time of such conduct as a result of a mental disease or defect, he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law.” It seemed not to matter that as hard as the courts tried to define the limit and scope of a defense based on mental state of a defendant at the time of offense, there was always a problem with its application. By 1972, however, the Durham test, as an effective standard for the nation’s courtrooms, was over. It was simply too broad and gave the psychiatric profession too much power in criminal court. But no single case caused the Durham experiment to fail. Rather, it was “the accumulation of eighteen years of problems and patchwork solutions and, above all, to simple exasperation” (Maeder, 1985, p. 95). However, the newer guidelines provided the foundation for a wide array of ingenious, and some say frivolous, defense strategies. One of the most famous was the “Twinkie Defense” of the late 1970s.

“Law is a bottomless pit!”

John Arbuthnot (1667-1735) English physician.

(CORBIS)

In a notorious murder trial that took place in San Francisco in 1979, a former police officer, Dan White, was accused of the murders of Mayor George Moscone and an administrative aide named Harvey Milk. That White committed these murders was never in dispute, since he shot both men at mid-day inside City Hall. But at trial the defense claimed that White was suffering from a mental lapse brought on by a series of events in his life that left him temporarily insane. Psychologists who testified at his murder trial postulated that White was not responsible for the murders, even though he carried extra ammunition with him to City Hall and reloaded between killings. His attorney said that a depression put him into an altered state that changed his behavior to such a degree, that he began to eat junk food. Something he had never done before, according to his defense.

One psychiatrist testified: “I think that on the day of the crimes he really had no meaningful, rational capacity to carefully weigh the considerations for and against and rationally decide on a course of action. He couldn’t think carefully about what he was going to do” (Winslade, 1983, p. 47). Although it was later called the “Twinkie Defense” by the local press, the correlation between junk food and White’s behavior was never made at the trial. This was a falsehood that has been repeated many times in hundreds of press accounts of the trial. White’s attorney’s offered evidence that the previously health conscious defendant began to eat Twinkies and other junk food as a result of his severe depression. But the characterization stuck and the Dan White case will always be remembered as the time junk food caused a man to go crazy and commit murder.

White was convicted of manslaughter and, as a result, he received a much lighter sentence as opposed to a 1st degree murder conviction. The decision ignited riots in San Francisco’s gay community. Of course, this type of defense is not as common as the press believes, but it demonstrates what can be done under the elusive definitions of the Durham Rule and “diminished capacity” defenses. Eventually, the Durham rule was abandoned in favor of the “substantial capacity test.” This criteria was, in effect, a combination of the M’Naghten Rule and the Irresistible Impulse test. Under M’Naghten alone, a defendant was required to show a complete failure to distinguish between right and wrong. This compromise, at least to some, seemed acceptable to the courts. For Dan White though, the “diminished capacity” defense worked. He spent 5 years in prison for a double murder and was paroled in 1985. A few months later, Dan White committed suicide.

“A lawyer is one skilled in the circumvention of the law” Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914)

(POLICE)

An even more disturbing case than the “Twinkie Defense” took place in New York City in the late 1970s. Officer Robert Torsney, 34, was an eight-year veteran of the N.Y.C.P.D. On Thanksgiving Day, 1976, he was scheduled to work a night tour and was extremely unhappy about being away from his family. In his police memo book, which is a diary of each officer’s work day, Torsney wrote “Happy Working Felony Thanksgiving” for that day’s entry (Dunning, p. B. 3). That night, he and his partner received a radio dispatch to respond to the Cyprus Houses, a public housing development in East New York, Brooklyn. The job was “man with a gun.” They investigated the job without incident and after taking some information from a few tenants; they exited the building onto the street. Outside, the young officers confronted several teen-agers. One of the teen-agers, a Randolph Evans, 15, called out to Torsney and asked if his apartment was searched. Without warning, Torsney suddenly pulled out his service revolver and shot the boy dead from a distance of about two feet. Torsney later testified: “He was talking to me. I don’t remember exactly. I remember not being in my body sort of” (Dunning, p. B3). The cop walked over to the police car without saying a word and sat in the front seat. Torsney was later arrested for this cold-blooded killing, which was widely reported in the press (Raftery and Singleton, p.3).

His murder trial began in November of 1977 against a backdrop of racial suspicion and accusations. Torsney was white and Evans was black. Officer Torsney later told a psychiatrist: “I can’t say I like back people, but I don’t let that affect me. There is a lot of violence down there. My life is in danger” (Winslade, p. 141). One defense witness was Dr. Daniel Schwartz, chief of forensic psychiatry at King’s County Medical Center, a familiar witness in New York City’s courts. In previous years, he had been appointed to examine David Berkowitz, the “Son of Sam” killer and David Chapman, assassin of Beatle John Lennon. Up to that time, Dr. Schwartz testified in well over 100 trials. After interviewing Torsney on 3 occasions, Dr. Schwartz concluded that the officer fired his weapon while he was suffering from a psychomotor seizure, a sort of mini-stroke which leaves no tell-tale signs and may never return again. Dr. Schwartz claimed that Officer Torsney suffered from an extremely rare condition called Automatism of Penfield (Winslade, 1983, p. 141). Apparently, this affliction was so rare that few had ever heard of it before the trial. But Torsney’s testimony was in direct conflict with psychiatric opinions of his behavior. His statements in court claimed self-defense. “He (Evans) was still talking and pulling out a silver object which looked like the barrel of a gun” he told the court (Dunning, p. B3). Even so, after just several hours of deliberations, the jury found Officer Torsney not guilty by reason of insanity.

Over the next few years, the New York mental health community struggled with how to deal with Officer Torsney, who was convicted of no crime, showed no signs of being mentally ill and yet was commanded by the courts to remain in a mental hospital to be treated for a disease which didn’t exist. After two years of wrangling with the courts, during which Tornsey was often permitted to come and go at will and spend most of his time at home with his family, he became a free man. Justice, at least the way it was defined in this case, had been served.

“A psychiatrist is a fellow who asks you a lot of expensive questions your wife asks you for nothing” –Joey Adams, U.S. comedian.

America’s standards for the insanity defense, during the period 1954-1984, received a great deal of criticism because of cases like Torsney and White. Psychiatrists were given a powerful voice in the nation’s courts and the results could often be infuriating to the public. Psychologists, whose profession revolves around the endless ambiguities of the human mind, were asked to make decisive judgments about an individual after seeing a prisoner only once or twice. This was absurd according to many people. Sometimes psychologists treat their patients for years in dozens of sessions without coming to a solid conclusion or understanding of their mental problems And those judgments by court appointed psychiatrists could have a tremendous impact on a criminal trial and its outcome. “Psychiatrists and psychologists are often put in the same position as economists who are asked to predict things that no one is capable of predicting. Those with the honesty and realism to say they can’t do it are likely to be brushed aside…” writes Thomas Sowell in The Insane Insanity Defense (Sowell, 1994, p. A10).

Psychiatrists also have been known to slant their findings toward the side that pays them. This is a dangerous tendency that corrupts testimony and blurs the truth in front of a jury who is already suspicious of “expert” psychological testimony. That suspicion has been fostered by some spectacular failures and abuses by psychiatrists who explain the behavior of criminals with the twisting idiom of clinical definitions. And psychiatrists themselves are notorious for their disagreements on the same issues. For every psychiatrist that testifies on the stability of a defendant, another one will quickly follow who will testify to a completely opposite conclusion. Frequently, there is no common consensus among psychiatrists, a fact that has devalued the profession in the eyes of the public and lessened the impact of their testimony in a court of law. What does it matter if a defendant had a less than perfect childhood? How does that relate to a vicious murder that may have been committed twenty or thirty years later? Or as Thomas Maeder writes in Crime and Madness, “It (psychiatric testimony) can send him to prison, or send him to a hospital, or put him on probation, and what is it that you need to know to make that decision? Do you need to know that the person had a poor upbringing, that he masturbated as a child? Just what is it that you need to know?” (Maeder, 1985, p. 100).

There is also the natural danger that clinicians mostly identify with those on their own economic and social level. When dealing with patients who are much different than themselves, psychiatrists can be oblivious to their problems. One forensic psychologist went so far as to say: “I hate to say this, but I don’t like to work with poor people…They are talking about stuff that doesn’t interest me” (Rowe, 1984, p. 325). Undoubtedly, few doctors could be as honest. Another common problem is forensic psychologists are paid professionals and therefore, usually accessible to only the wealthy class. Such a case was the strange story of John du Pont, heir to the du Pont family fortune and the wealthiest man ever to be charged with murder in American history.

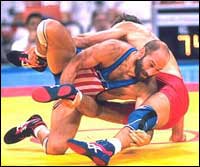

“I’ve fully concluded that I was ill…” multi-millionaire John du Pont as he apologized for killing Olympic wrestler Dave Schultz on January 26, 1996.

In the Fall of 1995, the local police were called to the 800 acre estate in Pennsylvania of John du Pont, 57, an heir to the du Pont chemical fortune. Newton Police Chief Lee Hunter went to the du Pont mansion as a result of a request by the family lawyer. When the police chief arrived, John du Pont told him that he thought he was attacked in his sleep by a wrestler who was living on his property. Du Pont was an avid wrestling fan and donated large sums of money to the Olympic wrestling team. At that time, his wealth was estimated to be $250 million dollars. In the private gym where the athletes trained, a plaque read “You can’t just take it to the top. You have to take it over the top.” Du Pont told Chief Hunter that there was a conspiracy to ruin his name and if it wasn’t stopped, the Russian Army was sure to invade Newton township. During the conversation, Du Pont referred to himself as the “Holy Child” (U.S. News, Jan. 30, 1997)

On January 26, 1996, du Pont, his mental condition deteriorating and feelings of acute paranoia consuming him, drove over to the home of David Schultz, a 1984 Olympic gold medallist, who lived in a house on du Pont’s estate. While Schultz’ wife looked on in horror, du Pont shot and killed David with a .38 caliber handgun in the driveway of his home. Immediately after the shooting, du Pont went back to his mansion where he held off an army of police for three days. He was arrested when he ventured outside his home to fix a heater, which police had turned off.

In court, du Pont’s lawyers pleaded an insanity defense. They said his mental condition had gone downhill ever since is mother died in 1988. Afterwards, he took to wandering his vast estate armed with handguns and acting erratically. He believed he was the Dalai Lama and spoke of himself in exalted and exaggerated terms (U.S. News, p. 1). There were also rumors of cocaine use and du Pont told friends he believed he was about to be assassinated. Psychologists testified that du Pont was mentally unbalanced and could not be held responsible for his conduct. Du Pont himself later said, “I wish to apologize to Marty Shultz and her children. I’m very sorry for what happened” (U.S. News, p. 1). But the insanity defense was eventually rejected. The prosecution was able to show that du Pont knew that what he did was wrong and appreciated the wrongfulness of his conduct. They used his three-day stand-off as evidence that he knew shooting Shultz was wrong and that he knew could be arrested for the killing. During that standoff, du Pont asked for his lawyer over 100 times, indicating that he was fully aware of the nature of his act and the need for legal representation. After seven days of deliberations, he was found guilty of 3rd degree murder and sentenced to 13 to 30 years (U.S. News, May 12, 1997).

“History is the sum total of things that could have been avoided“

Konrad Adenauer (1876-1976), Former Chancellor West Germany .

The acquittal of John Hinckley in 1982 set off a groundswell of criticism against the insanity plea. It was thought that lawyers had manipulated the courts and abused constitutional protections in order to set a guilty man “free.” Many people, lawyers, legislators and newspaper editors, called for the abolition of the insanity defense. Over the next few years, thirty-nine states made dozens of changes in their laws regarding insanity pleas. Utah and Idaho completely abolished the defense at criminal trials. There was a strong perception that the insanity defense was a “loophole” in the law that let murderers escape justice. Congress passed major legislation which made sweeping changes in the way the insanity plea is used in American courts.

But it’s not only defendants and attorneys who manipulate the insanity defense. Journalists and politicians also abuse the NGRI plea for their own reasons. Politicians use it as a vehicle to capture the public’s attention and journalists report on it because they are aware there is a great deal of public interest in the subject. But rarely do they explore the issue with the kind of attention and accuracy it deserves. As we have seen, statistics confirm that the plea is vastly exaggerated as a “loophole” and rarely does it get anyone off a criminal charge. But the common understanding of the plea is exactly the opposite. Samuel Walker writes: “This misunderstanding explains the fact that nearly half thought it should be abolished and an incredible 94.7% thought it should be reformed” (Walker, 1994, p. 151). Of course, any criminal defendant can raise the issue of insanity, which is his or her right to do. Actually succeeding in that defense is another issue entirely. Even Kip Kinkel, 17, who shot 29 people in an Oregon school rampage in 1998, was unable to substantiate an insanity defense. So were David Berkowitz, Ted Bundy, Sirhan Sirhan, Henry Lee Lucas, Charles Manson and John Wayne Gacy.

But since the insanity defense is utilized almost exclusively in murder cases (it is extremely rare in any other type of offense), the publicity it receives is far out of proportion to its use. It has become part of the promotional apparatus of high profile criminal cases in modern times. The trials of Jeffrey Dahmer, Hinckley, David Berkowitz (The Son of Sam Killer) and the Lorena Bobbit mutilation case, are simply not typical of most criminal trials held in America any more than O.J. Simpson was a typical murder defendant. It is simply incorrect to assume that what happened in the O.J. Simpson trial happens in murder trials across the country. And yet, it is not difficult to find a press story or a television talk show that laments the O. J. trial as symbolic of all of that is wrong with criminal justice in America. Nothing could be further from the truth, since the Simpson trial is about as far as one can get from the ordinary workings of our criminal justice system.

Legal scholars, judges, attorneys and clinicians have tried for hundreds of years to come to some sort of mutually acceptable understanding of what criteria should be used to gauge a person’s culpable mental state. It hasn’t been easy. The complex turnings of the human mind are not so easily deciphered according to a prepared script. Even if the insanity defense were eliminated tomorrow, it would not eradicate the issues under consideration. Defense attorneys would still have to address culpable mental state and so would prosecutors. Mens rea assessment is open to either side.

Consider the Jeffrey Dahmer case. Dahmer was arrested in Milwaukee in 1991 after he had killed at least 13 victims. His apartment contained the remains of many young men who he had brutally murdered and dissected. He poured acid on his victims, cut them into pieces and preserved their heads and genitals. He treated, preserved and decorated the skulls of his victims. His crimes are a litany of perversion and torture that is rare even for sexually motivated serial killers. In court, his attorneys attempted to plead Dahmer not guilty by reason of insanity. But prosecutors were able to prove that Dahmer knew full well that killing was against the law and what he was doing was wrong. The insanity plea was not accepted in his case. If someone like Dahmer could not be categorized as legally insane, then it stands up to reason that the criteria for insanity must surely be a difficult standard to meet.

This is the reality of the insanity defense in America: difficult to plead, seldom used and almost never successful. But in that small number of cases where it is successful, it is sometimes manipulated or abused in a way that often grabs headlines and captures the imagination of the public. Ultimately, only a jury can decide the issue of insanity, which in itself may be the most controversial aspect about the insanity defense. In other words, people who have no training in the field, rarely come into contact with the mentally ill and have a minimal understanding of the issues involved, make legal, long-lasting judgments that are frequently based on shifting criteria. Or as U.S. journalist Bugs Baer (1886-1969) once wrote: “It’s impossible to tell where the law stops and justice begins!”

American Psychological Association. Myths and Realities: A Report of the National Commission on the Insanity Defense. January 9, 1996

Dunning, Jennifer. “Police Officer Tells How He Shot Youth”. New York Times, November 18, 1977, p. B3

“Encarta 2000” CD Microsoft Corp.

Friedman, Lawrence (1996) Crime and Punishment in American History. New York City, NY: BasicBooks Publishers

Knappman, Edward W. (1994) Great American Trials. Detroit, MI: Visible Ink Press

Marino, Kim Prof., PhD. Professor of Criminal Justice. Iona College, New Rochelle, New York provided suggestions and other assistance in the preparation of this article.

McNulty, John. “Squelch Esposito Break At Gates of Death House”. New York Daily News. May 8, 1941, p. 4)

Maeder, Thomas. (1985) Crime and Madness. New York City NY: Harper and Row Publishers

Melton, Gary B., Petrila, John, Poythress, Norman G. and Slobogin, Christopher (1997). Psychological Evaluations for the Courts. A Handbook for Mental Health Professionals and Lawyers. New York City, NY: The Guilford Press

Menninger, Karl (1968) The Crime of Punishment. New York City, NY: The Viking Press.

U.S. News. www.cnn.com January 12, 1977, May 12, 1997

Raftery, Thomas and Singleton, Donald. “Charge Cop With Slaying of Boy, 15.” New York Daily News, November 27, 1976, p. 3.

Rowe, Jonathan (May, 1984) “Why Liberals Should Hate the Insanity Defense”. The Atlantic Monthly

Siegel, Larry J. (1998) Criminology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co.

Sowell, Thomas (1994), “The Insane Insanity Defense. Albany Times Union, February 16, 1994

Walker, Samuel (1994) Sense and Nonsense About Crime and Drugs. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company

Winslade, William J., Ph.D, J.D. and Ross, Judith Wilson (1983). The Insanity Plea. New York City, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons