LAPD finds killer of Vietnamese engineer — The Crime — Crime Library

Watch LA Forensics Wednesdays at 9:30pm E/P to learn more about this case and others like it.

Editor’s Note: The names of the victims in this story have been changed to protect their identities.

LOS ANGELES The body was still smoldering when the police got to the scene. It was burned so badly that at first glance they couldn’t tell its age, race, or even sex. The one thing they could tell was that the body had been bound hand and foot. It had also been gagged. Barring some kind of Houdini act gone awry, this was clearly a case of murder.

A detective marked his arrival time in his notebook: 7:30 p.m., November 8, 1989.

Forty minutes earlier, a school system employee drove a shortcut through an abandoned neighborhood in Westchester, on the northern edge of the Los Angeles airport, and spotted something burning on a driveway leading to an empty lot where a house once stood. The school employee stopped his car and jumped out cradling a fire extinguisher. After beating down the flames, he took a long look at the 100-plus pound sizzling lump lying on the driveway. Slowly, it dawned on him that the thing he was staring at was a human being.

A short time later, homicide detectives from LAPD’s Pacific Division cordoned off the crime scene and began an hours-long systematic search for evidence. Assisting them were criminalists from SID, the department’s Scientific Investigation Division.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

The area immediately north of the airport was a 200 to 300 yard deep, nearly mile-and-a-half wide, slightly crescent-shaped swath of tree-dotted vacant lots, deserted streets, and empty cul-de-sacs. It was bordered on the north mostly by 91st Street, Pershing Drive to the west, and on the east by Lincoln Boulevard.

The area had once been a tract housing development, but the airport bought the property and leveled the houses. All that remained were the streets and driveways, faint outlines of a once-bustling community that had been erased from the landscape.

Contracted by flames, the body lay curled in a fetal position. As detectives examined it more closely, they noticed the scorched remnants of a light blue shirt and dark pants, then what appeared to be a white undershirt and a pair of boxers. Judging by the clothing, the victim was most likely male, but most of the hair and face had been burned away, making further identification at the scene impossible.

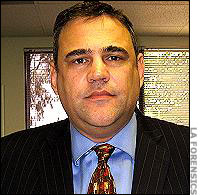

“The body was charred to the point where we could not recognize the race or the age of the person,” says Detective Patrick Barron. “You could tell that he had been bound with duct tape. The duct tape was still affixed. Parts of it had been burned, but you could tell the hands and the ankles had both been bound.”

Detectives scoured the ground around the victim for clues, but they almost missed the bullet. Under the floodlights set up around the crime scene, the bullet looked like a bump in the concrete or a piece of gravel.

“We were there more than an hour before we noticed the slug,” Barron says. “And, quite frankly, I was in the middle of something and my partner said, ‘Hey, is that a bullet?'”

It lay nearly a dozen feet away from the body and had dug a divot into the driveway. To the cops, it appeared to have come from either a .38 or .357-caliber revolver. Both pistols use the same bullet. The only difference is that the .357 cartridge has a slightly longer shell casing and holds a little more gunpowder. The extra charge gives it more velocity, and thus produces more energy on impact.

Investigators also found a plastic bottle, an empty pack of smokes, and a matchbook with the name of a bail-bond company that immediately captured police attention.

There was also a fresh tire track on the street, a skid mark really, pressed into a patch of sandy dirt that had pooled on the concrete.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

The dead man had what appeared to be a bullet hole in his back, near the right shoulder blade, and a slightly larger one in the upper part of his right chest. Detectives surmised he’d been shot in the back while lying facedown on the driveway. The bullet had gone all the way through his body.

The man carried no identification. There was no car nearby. There were no witnesses. It looked like a dump job with the coup de grace being delivered in the driveway. The spot was one of the best in Los Angeles to carry out an execution.

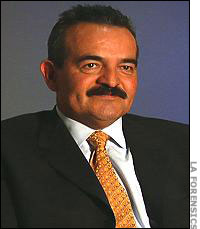

“It’d be a perfect place if you’re going to dump a body,” says L.A. County Deputy District Attorney Michael Duarte, “because there’s nothing around, and plus all the noise from the jets, the landings and the take-offs, you can’t hear anything so nobody’s going to be able to hear a gunshot.”

The detectives realized that not knowing the identity of the victim was going to hinder the investigation right from the start.

A guiding principle of homicide investigation is that the most important part of a murder victim’s life is the last 24 hours. Most murders aren’t planned out in advance. They’re crimes of passion, spur-of-the-moment killings. In most cases, something the victim did during those last 24 hours led directly to his or her death. If investigators can accurately recreate the last day of a victim’s life, they can solve the case. But not knowing the name of the victim makes it impossible to recreate those last crucial hours.

“Without an identity on the victim, the case could grow cold very easily,” says SID forensic specialist Scott Hurwitz. “Having the victim’s I.D. will help us find where he was last, and possibly find the suspects.”

The Los Angeles coroner tagged the body John Doe No. 225.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

The post mortem medical examination of John Doe No. 225 revealed that he had suffered an even more horrifying death than the cops had imagined he had been burned alive.

The autopsy uncovered soot in the man’s nostrils, his trachea, and his lungs, indicating he was alive when he had been set on fire. He’d also been beaten savagely just before his death. And he’d been sodomized.

“This poor man…what they did to him,” Deputy D.A. Duarte says. “This was horrible, horrible, one of the most horrible cases I’ve seen.”

Meanwhile, detectives continued to try to identify their victim. The medical examiner had pegged him as a middle-aged Asian male. He was 5 feet 9 inches tall and weighed 115 pounds at autopsy. In life he had been maybe a buck twenty, a buck twenty-five. Either way, not a very big man.

Detectives read recent missing persons reports and soon found one that looked promising. Just hours before they discovered the burned body near the airport, someone had filled a report with the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department about a missing 53-year-old Asian man named Lon Kim. Mr. Kim was an engineer and real estate investor from the affluent Los Angeles suburb of Rancho Palos Verdes.

Mr. Kim’s wife had reported him missing after he didn’t come home from a short trip into South Central L.A. to collect rent money at an apartment building he owned.

Detectives contacted Mrs. Kim.

“His wife was frantic to hear what had happened to him and where he was and what the situation was,” Barron says.

As an immigrant, Lon Kim had been fingerprinted when he came to the Unites States. Detectives got a copy of the fingerprint card and his dental records to compare to their victim. They matched.

John Doe No. 225 was Lon Kim.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

To Michael Duarte, Lon Kim’s story was part of what makes the United States such a great country.

“He was from Vietnam,” Duarte says. “(He) came to the United States with nothing, went to DePaul University, got a degree, moved to California, started working as an engineer and started his own real estate business on the side. As a result of that, (he) owned some apartment complexes in Southern California. It’s the American dream, the immigrant success story.”

On the day he disappeared, Lon left home in his 1983 Mercedes 240D to drive into Hawthorn, in South Central L.A., to an 18-unit apartment building he owned. He told his wife he was going to pick up rent from a couple of tenants.

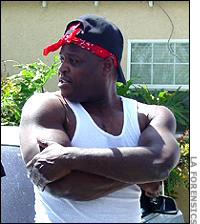

One of Lon’s tenants, Kerry Ephriam, a hospital security guard, owed more than $2,000 in back rent. He had sent Ephriam several letters about the rent. None had been threatening. There was no mention of eviction. That wasn’t Lon’s personality. He had simply asked Ephriam to pay what he could, even if it was as little as $50.

Earlier that day, Kerry Ephriam’s brother, Kacey Ephriam, called Lon’s house and left a message with his wife. Kerry had $40 to pay toward his rent, Kacey said. That afternoon Lon went to meet with Kerry Ephriam.

He never came back.

When detectives found out what Lon had been doing just before he disappeared, they canvassed the apartment building. They knocked on all 18 doors and talked to every resident they could find. A couple of people said they had seen him at the building that day.

The detectives also talked to Kerry Ephriam.

Ephriam said that just before he left for work he gave Mr. Kim $900 in cash. But there was a problem with Ephriam’s story, which the homicide cops quickly uncovered.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

When detectives went to the hospital where Ephriam worked as a security guard, his boss, the security supervisor, said Ephriam hadn’t been at work on November 8. He showed the detectives Ephriam’s time card to prove it.

Even more troubling, the cops found out that Ephriam had called and asked another employee to lie for him. If the cops came by the hospital asking questions about him, Ephriam wanted the employee to back up his claim that he had been working that day.

It seemed like a stupid lie to tell experienced detectives. Ephriam had to know they were going to check out his story.

“Some of these criminals are not that smart,” Duarte says. “If they were smarter, it would probably be a lot more difficult to catch them. He probably thought he was smarter than the detectives.”

Another thing investigators realized after they talked to the hospital security supervisor was that it was unlikely Ephriam had paid Mr. Kim $900. That amount was three times Ephriam’s weekly paycheck. If Ephriam had that kind of money, he probably would have paid his rent instead of going in the hole more than two grand.

When Detective Barron and his partner went back and confronted Ephriam about his lies, the squirrely security guard changed his story. He hadn’t given Mr. Kim $900 in cash, he admitted, but he had given him one of his paychecks to put toward his back rent. Ephriam then claimed that as Mr. Kim was leaving the apartment building, three black guys, probably gang members, grabbed the building owner at gunpoint. The gangbangers shoved Mr. Kim into his Mercedes and sped away. Ephriam said he had not reported the incident to the police.

Coming on the heels of Ephriam’s lie about working the day Lon Kim disappeared, the new gang kidnapping story seemed ridiculous. Ephriam had tipped his hand and Detective Barron had seen it. “I knew (then) that he was one of the significant players in the murder.”

But the investigators needed to do more than expose Ephriam’s lies. They needed to find evidence, hard physical evidence.

Soon they would have it.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

Lon Kim had worn the same Omega watch for 25 years. According to his wife, strapping his timepiece on his arm was a morning ritual. He never left home without it.

When the police found his body on November 8, he was not wearing his watch.

“We’ve got a burned body that has no watch,” Barron says. “It means that watch is somewhere, which normally is going to mean somebody took it, and if they took it off of him, they kept it, sold it, pawned it or gave it to somebody else.”

It took a lot of searching, but detectives with the pawn shop detail found a pawn ticket for Lon Kim’s watch. A man named Michael Valentine had hocked it a few days after Lon’s murder. Under state law, to pawn the watch, Valentine had to show a California identification card and leave a thumbprint on the pawn ticket.

It was the break the detectives had been looking for. None of the other evidence the items recovered from the crime scene they thought were important had panned out. The tire track, which the crime lab said had most likely been made by an Oldsmobile, was useless to the detectives unless they found the tire that left it. Nor had SID found any identifiable fingerprints on the cigarette pack or the plastic bottle. And it turned out that the bail bondsman’s matchbook was a marketing tool, just one of hundreds, perhaps thousands that had been passed out around Hawthorn and throughout South Central L.A.

“It was a dead lead,” Barron says.

But another break was on the way.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

Lon Kim’s Mercedes had been missing since his disappearance. Uniform cops found it several days later, abandoned on a street in Inglewood. They had it towed to SID.

“When we (got) the vehicle it was totally stripped,” says SID’s Scott Hurwitz. “The radio was missing, the interior was all torn up, and a lot of parts were stolen out of it.”

The missing stereo was an expensive German-made Blaupunkt.

The police had found the Mercedes four blocks from the residence of the man who had pawned Lon’s Omega watch, Michael Valentine.

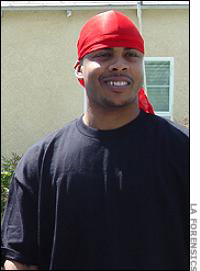

“Michael Valentine was a big badass,” Detective Barron says. “He had history of robberies, was a known gangster, in and out (of jail), involved in crime all the time.”

Valentine was a member of the Bloods, the smaller though many experts say the more violent of the two huge, mostly-black, L.A. street gangs. The other gang was the Crips. Kerry Ephriam had connections to the Crips, although as far as investigators could tell, he wasn’t a full-fledged member.

In the late 1980s, the urban guerilla war between the Bloods and the Crips raged across Los Angeles. The two gangs were mortal enemies, yet Michael Valentine and Kerry Ephriam appeared to be linked to the same murder. What was their connection?

The answer would surprise the detectives and provide a crucial clue to who killed Lon Kim and why.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

Not long after investigators identified Michael Valentine as the man who’d pawned Lon Kim’s watch, an anonymous tipster called the Pacific Division. Out on the street, Valentine had been bragging about a recent murder.

“Michael said that he had killed somebody and the guy was supposed to have a lot of money on him, but he wound up having only $41,” Barron says.

A second caller told police that the person Valentine had bragged about killing was carrying just $21.

“One of the tips said forty-one, one of the tips said twenty-one,” Barron says, “and throughout the case, it’s never been resolved whether the actual take of the heinous murder was forty-one or twenty-one dollars.”

Detectives went looking for Valentine but couldn’t find him. His mother claimed not to know where he was or how to reach him. The cops let her ramble. Finally, Ms. Valentine let something slip. She and Kerry and Kacey Ephriam’s mother were sisters, which made Michael, Kerry, and Kacey cousins.

Suddenly, the connection despite the different gang affiliations made sense. The murder of Lon Kim wasn’t gang related. It was family related.

Ms. Valentine threw up a lame alibi for her son, but she didn’t know how much the detectives already knew, and what she said put her son even closer to the crime.

“The mother’s statement was that Michael was drinking beer with his two cousins, Kerry and Kacey, at Kacey’s residence,” says Pacific Division homicide supervisor Mike DePasquale. “That turns out to be a block away from where the victim’s car was recovered.”

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

Pacific Division detectives were ready to make their move. So far, they had Kerry Ephriam caught up in several lies. They had Michael Valentine pawning Lon Kim’s watch. They had Lon’s car found stripped four blocks from Valentine’s house. They had two anonymous callers saying Valentine had been boasting recently about robbing and killing someone.

The detectives got three search warrants and hit all three residences Michael’s, Kerry’s, and Kacey’s simultaneously.

Not surprisingly, Michael, who knew the cops were looking for him to question him about a murder, wasn’t home. Also not surprisingly, his mother claimed to be in the dark about where he was. The investigators combed through Michael’s house but didn’t find any additional evidence linking him to Lon’s murder; however, they did find Valentine’s work tools a sawed-off shotgun and a military-style assault rifle.

At Kerry’s apartment, SID used what in 1989 was a new weapon in their arsenal, luminol and black light. Luminol is a chemical agent that reacts when it comes into contact with the iron in blood hemoglobin. In low-light conditions and under a black light, that reaction is luminescent it glows.

Inside Kacey’s apartment, SID criminalists covered the windows, then sprayed a luminol solution on nearly all of the flat surfaces. Then they doused the white lights and turned on the black ones. From two locations, the edge of a rug and a tiny spot on one wall, came a faint blue glow. It was blood.

“I was flabbergasted,” Barron says.

He didn’t believe in the newfangled technology, but here it was working.

“Wow, it’s glowing,” he says. “I mean, it was impressive because this is 1989. It was new. We had heard about it, and it sounded like something the FBI could afford to do but not us.”

SID lab tests later confirmed the blood was human.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

As the Pacific Division detectives approached Kacey Ephriam’s door, Barron noticed a blue Buick Electra with a strip of duct tape holding up the rearview mirror parked out front. Duct tape, Barron thought, exactly what had been used to bind Lon Kim’s hands and feet and to gag his mouth.

Kacey answered the detectives’ knock. It wasn’t a police reality show. There was no SWAT team, no helicopters, no battering rams. Just a squad of well-dressed detectives. They told Kacey they had a search warrant and he let them inside.

Barron casually asked Kacey who owned the Buick. Kacey said it was his.

“Is it okay if we look through your car?” Barron asked.

Kacey said it was fine with him as he handed the detective the keys. Barron stepped outside and popped open the Buick’s trunk. The first thing he spotted was a roll of duct tape. He poked around for another minute then closed the trunk lid. He’d already seen enough to know he was going to impound the car and tow it to SID.

If the forensic specialists could match the duct tape in the trunk to the tape found on Lon Kim’s body, the detectives would have their first solid piece of evidence implicating Kacey in the murder plot. If the detectives got really lucky, the forensic team might find additional evidence inside the car, or outside, like tires that matched the tracks left at the crime scene.

Barron tried not to let his excitement show.

“Inside, I’m doing somersaults,” he admits.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

As the detectives searched the house, Kacey watched Barron dig through a bedroom closet. At the bottom of the closet, Barron found a soft case for a guitar. When he squeezed the case he felt something hard inside, something much smaller than a guitar. He reached in and pulled out a gun, a .38-caliber revolver. It was the same kind as the gun used to shoot Lon Kim in the back.

Barron turned and smiled. “I looked over at Kacey and saw this change on his face,” the detective recalls. “He had given us this story how he could never be involved with something like this. He was waiting to go into the Marines, and he was going to be gone in about six weeks.”

Barron arrested Kacey Ephriam for the murder of Lon Kim.

As the detectives made their way out of the house, with the gun in hand and Kacey in tow, one of them said to Barron, “Weren’t you looking for an Oldsmobile?”

Parked next to the house was a tan 1980 Oldsmobile Cutlass that belonged to Kerry and Kacey’s mother. The detectives took that car with them, too.

Later, SID searched the Oldsmobile and found a human hair in the trunk. Testing revealed the hair had come from the head of someone of Asian descent, someone like Lon Kim.

“The only plausible explanation for Lon Kim’s head hair to be in the trunk of the Oldsmobile was that he was transported in that car,” says SID trace evidence specialist Doreen Hudson.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

Forensic scientists at LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division also compared the tires on the Olds to the tread mark left at the crime scene. “They were a match,” Barron says. “The SID people made the match. It was just icing on the cake.”

The crime lab also had good news about the roll of duct tape Barron found in the trunk of Kacey Ephriam’s Buick Electra.

“The tape that was found on the victim came from the roll of tape found in the suspect’s vehicle,” says SID’s Doreen Hudson. “The likelihood of having a physical match between two different rolls is…it’s almost nonexistent.”

But murder is about killing, not rolls of tape or strands of hair. According to the autopsy report, Lon Kim “sustained multiple injuries consisting of multiple blunt force trauma, a gunshot wound of the right back, and extensive thermal burns with smoke inhalation after being bound, gagged and probably sodomized. The gunshot wound…resulted in perforation of the right lung leading to…his death.”

Of all the terrible injuries Lon Kim suffered, it was a gunshot from a .38-caliber pistol that killed him, and Detective Patrick Barron had found in Kacey Ephriam’s closet a JLG .38-caliber revolver, a brand well-known to detectives.

“It’s cheap,” says homicide Detective Mike DePasquale. “It’s what we call a Saturday night special. Those are guns you can buy anywhere. You don’t have to buy them at a gun store. Some of those guns are fifty to a hundred dollars.”

SID test fired the JLG .38 and then used a comparison microscope to do a side-by-side examination of the test bullet and the one found at the crime scene.

They matched.

According to the Firearm’s Unit, the gun found in Kacey Ephriam’s closet fired the bullet that killed Lon Kim.

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

After the successful series of search warrants, investigators had Kerry and Kacey Ephriam in custody, both charged with murder, but they didn’t have their cousin, Blood gang member Michael Valentine. He was in the wind. Barron and his partner had a murder warrant issued for Valentine’s arrest.

Not long after the arrest warrant was issued, uniform cops in South Central L.A. pulled over a Dodge Aries for a traffic violation. The driver turned out to be Michael Valentine. The cops, who were used to dealing with gang punks, threw a pair of handcuffs on Valentine and notified detectives they had collared the fugitive murder suspect.

When detectives searched Valentine’s raggedy Dodge, they found a high-end German-made Blaupunkt stereo mounted in the dashboard. It was the same stereo that had been in Lon Kim’s Mercedes.

“The radio was probably worth a third of the value of the car,” Barron says.

But the Blaupunkt stereo and the Omega weren’t the only things tying Valentine to the murder. Detectives also found a witness who linked him to the murder weapon.

The witness told investigators that when Michael dumped the Mercedes in Inglewood, Kasey was following him in the tan Oldsmobile. As the two men talked in the street for a few minutes, they stood protectively over the trunk of the Oldsmobile. Valentine was carrying a gun, which one the witness later described as “a cowboy-looking gun,” meaning a revolver. The witness also overheard part of Michael and Kacey’s conversation.

“Michael Valentine handed the gun to Kacey Ephriam and told him, ‘Take him to a deserted area and to shoot him and set him on fire.'” Deputy District Attorney Michael Duarte says. “And that was approximately three to four hours before Lon Kim’s body (was) found at the airport.”

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.

Kerry Ephriam pleaded guilty to murder. His brother Kacey and cousin Michael Valentine went to trial. Both were convicted of murdering Lon Kim. Kerry was sentenced to approximately 30 years. Kacey and Michael each drew life sentences.

Although prosecutors don’t have to prove why someone committed a crime, only that the person charged committed it, Deputy D.A. Michael Duarte, who prosecuted the case, thinks he knows why Lon Kim was killed:

“The motive was twofold in this case. First of all, Kerry wanted to relieve his debt with Lon Kim. That was number one, and the way to do that was to get rid of Lon Kim and claim he had repaid him and somebody else committed this murder. Secondly, they wanted to rob Lon because they knew that he always carried cash because he was collecting his own rents.”

For Michael Duarte, the Lon Kim case was one of the most disturbing of his career.

“It was horrible what they did to him,” Duarte says. “You’ve got Michael Valentine, who’s just huge, right out of prison. He’s all buffed up. I mean, they’re pistol whipping (Mr. Kim) with this gun after they’ve tied him up with duct tape. And then they put him in the trunk of this car. This poor man, he can’t even move, can’t breathe. Then they take him out to the crime scene, tied up, and then they set him on fire and then shoot him in the back. And we know that when he was set on fire he was still alive.”

The punishment didn’t fit the crime, Duarte says. “I really believe they should have gotten the death penalty.”

Watch this story and many others from the case files of the LAPD’s Scientific Investigation Division, which solves crimes using cutting edge forensics. Only on Court TV. Learn more.