|

Detecting deception was paramount in

the Lindbergh kidnapping case. An entire nation demanded to

know the truth, and initially there were several suspects, one of

whom committed suicide within moments of being questioned. In

those days, the polygraph was a new device and the experts wanted to

test it, but it was resisted on all fronts—except by the one

person who might have benefited most.

On the evening of March 1, 1932, just

outside Hopewell, New Jersey, the twenty month-old baby of Charles

and Anne Lindbergh was stolen from his crib. It was a windy

night, and although Lindbergh had heard a strange crashing sound,

the dog had never barked to alert him to an intruder in the second

floor nursery. It was the nurse who discovered the child’s

abduction. Lindbergh called the police and roadblocks were

quickly set up around the state.

Then a search team got busy.

Inside the nursery, they found several clumps of yellowish mud, and

outside, a ladder lying in three sections on the lawn. One of

the sections had split along the grain. A set of footprints

was also noted, and a carpenter’s chisel was discovered near where

the ladder had stood by an open window.

An ominous envelope rested on the

windowsill, but Lindbergh left it untouched until the police could

handle it. Officer Frank Kelly slit it open and removed a single

sheet of folded paper. It read:

Dear Sir!

Have 50000$ redy with 25 000 $ in 20 $

bills 1.5000 $ in 10$ bills and 10000$ in 5 $ bills. After 2-4 days

we will inform you were to deliver the Mony.

We warn you for making anyding public

or for notify the Police the child is in gut care.

Indication for all letters are

singnature and 3 holes.

On the right-hand corner was a drawing

of two interlocking blue circles, an inch in diameter. The area

where the circles intersected was colored red, and three small holes

were punched into the design. Who had sent it remained a

mystery.

One week later, John F. Condon from

Brooklyn offered his services. A retired teacher, he had placed an

ad in the Bronx Home News, offering $1,000 of his own money.

He received a reply accepting him as a go-between, and Lindbergh

affirmed the appointment.

Condon then met a man named John in a

local cemetery to receive further instructions, and Lindbergh

prepared the ransom money. With the help of the IRS, two

packages of bills–$50,000 and $20,000–were made up, both

containing conspicuous gold certificates. The serial numbers

were secretly recorded.

Condon handed over the money, but the

directions to the baby proved to be false. Lindbergh returned

home empty-handed to his grief-stricken wife. They now

believed that their child might be dead.

On May 12, William Allen stopped his

truck on a road about four miles from the Lindbergh estate. He

walked into the woods and saw what appeared to be a child’s skull.

He contacted the police, who found the remains of a child in a

shallow grave. It was not long before Lindbergh positively

identified it as his missing son. Now the police were seeking

a murderer.

There were several leads, but all

quickly dried up. Curiously, a maid named Violet Sharpe, who

worked for Lindbergh’s in-laws, gave inconsistent stories. The

police questioned her several times and after one interrogation, she

swallowed a silver polish compound and was dead within minutes.

At this point, officials approached

Lindbergh about using a new lie detection instrument called a

polygraph on his servants. Leonarde Keeler was one of two

prominent criminologists who went to Hopewell to try to persuade

Lindbergh to accept their expertise in lie detection. Keeler

assured the state police that the polygraph had achieved a

ninety-percent accuracy rate.

Lindbergh rejected the proposal

because he did not believe that anyone who worked for him could be

guilty. However, that was not the last time that the polygraph

would be considered in this case.

That spring, the first gold notes from

the ransom money surfaced in several Manhattan banks, but no one

recalled who had brought them in. Finally, on September 15,

1934, over two years after the crime, a gas station manager wrote a

license plate number on a ten-dollar gold certificate used to buy 98

cents worth of gas. He remembered that the driver had spoken

with a German accent and had said that he had more certificates at

home. The license plate was traced to a carpenter named Bruno

Richard Hauptmann, who was arrested at once.

When police searched his home, they

discovered over $14,000 of the ransom money hidden between the wall

joists, $11, 930 beneath rags in a shellac can, and $1830 wrapped in

newspapers. They had no doubt that they now had the killer in

their possession. Later, the New Jersey State Police

discovered a missing rafter in Hauptmann’s attic that corresponded

to one of the uprights of the kidnap ladder. The case seemed

open and shut.

However, Hauptmann maintained that his former business partner,

Isador Fisch, had given him the money and then had died in Germany.

No one believed him.

Soon he went before the grand jury in New Jersey. At the

proceedings, Lindbergh testified that he had heard Hauptmann’s voice

in the cemetery when they had handed over the ransom money.

That was good enough for the court.

|

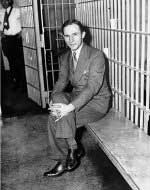

Bruno Hauptmann in jail

(AP) |

While in prison, Hauptmann learned about the lie detector machine

and asked to take the test, but inexplicably this was denied to him.

Since his defense attorney believed he was guilty, barely spoke to

him, and often showed up drunk at court, no one fought on

Hauptmann’s behalf to ensure that all possibilities were explored to

clear him. Although courts had already ruled the results of a

polygraph inadmissible, law enforcement had enthusiastically

embraced the procedure. Yet it was later learned that FBI

chief J. Edgar Hoover had scrawled on a memo, Under no

circumstances will we have anything to do with the [polygraph] test

of Hauptmann.

After a sensational trial, Hauptmann was found guilty and sentenced

to die. Then New Jersey’s Governor Hoffman, believing that

there was reasonable doubt, gave Hauptmann a short reprieve so he

could further investigate the case, and he believed that Hauptmann

ought to be given a lie detector test. Anna Hauptmann agreed

and went to Chicago to talk with Keeler.

He was eager to be involved, and to demonstrate the test’s

reliability, he used Anna as a subject. Reading off a list of

numbers, Keeler correctly judged her age when the needle on the

machine showed a change in her physiological response. She was

impressed. She returned to New Jersey to tell the governor

that Keeler would provide his services at no charge and in secret

from the press.

However, Keeler could not resist leaking the news and thereby blew

his chance to make a potentially monumental contribution to the

case. Instead, Boston attorney William Marston, who had a

different lie-detection technique, was brought in to perform the

test. He said it would take him two weeks, and arrangements

were about to be made when the trial judge denied Marston access to

Hauptmann. Hoffman’s hands were tied and the judge’s

resistance ended any further possibility that this device would be

used in the Lindbergh kidnapping case.

Yet there have been other cases in which the polygraph was actually

used, and the results still had little or no impact. This was

due to a monumental court decision about polygraph evidence that was

made back in 1923.

|