The True Story of Roy Brown and the murder of Sabina Kulakowski — Who Did It? — Crime Library

The small community of Auburn, New York is the setting of a story of two people who never knew each other, but who both became victims—one of a brutal murderer, the other of the justice system.

On the evening of May 21, 1991, a chain of events began in Auburn that would ultimately shake the community to its core and give the residents a taste of big-city crime that, until that night, they had only seen on television or read about in newspapers and magazines.

On that night, volunteer firefighter Barry Bench was awakened from a sound sleep by his ringing telephone. It was the Fire Chief, alerting him to a house fire out at Finger Lakes which he believed was at the home owned by Barry’s ex-sister-in-law, 49-year-old Sabina Kulakowski.

Barry rushed to don his uniform and jumped into his pickup truck. As he closed in on the fire, Barry realized that the chief was right: it was Sabina’s house. Once at the scene, Barry leapt into action to help extinguish the flames. When firefighters brought the blaze under control, the Chief approached Barry and told him he was sending in some men to see if Sabina or anyone else had been home at the time. Barry agreed to stay back, opting instead to take a look around outside.

The men had not been inside the home long when they heard Barry yelling. When the men ran outside, they found him standing over an object in the dirt road. When the men walked over for a closer inspection, they were stunned to discover the object was in fact the naked and lifeless body of Sabina Kulakowski.

After taking a moment to process the macabre scene, the Chief yelled to one of the firefighters to contact the Sheriff’s Department. Those at the scene couldn’t help but wonder how Barry had managed to walk directly to the body. They also wondered how Sabina had died. Could she have inhaled too much smoke escaping her burning house but only succumbed outside, or could she have had a heart attack from the overwhelming stress of the situation? Either scenario was plausible; however, neither explained why she had been nude when found.

By the next morning, news of the discovery had spread across Cayuga County like wildfire, making the headlines of every newspaper in the area. The community, with its close ties and small-town tranquility, assumed Sabina’s death had been a tragic accident; however, when the body reached the medical examiner’s office, the truth of her death came as a shock to everyone in the area.

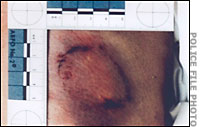

One of the first clues to cause of death that the medical examiner noticed was the identification of human bite marks on Sabina’s body, along with what appeared to be multiple knife wounds and ligature marks around her neck. She also had suffered defensive wounds on her hands, suggesting that she had struggled with her attacker. Her death obviously had been no accident, and the official ruling was homicide.

Detective Peter J. Pickney was assigned to investigate Sabina’s homicide. He knew the deceased casually and was aware of her former marriage to Barry’s brother. As far as he knew, the marriage had ended amicably, and he knew of no one who bore any ill will toward her.

Before her death, Sabina had been a social worker in the Cayuga County Children’s Protection Division. When Detective Pickney spoke with her supervisor, he was told that she got along well with coworkers and had not had any recent problems of which they were aware; however, her supervisor did say that she had had a problem approximately 8 months earlier, when she removed a 17-year-old girl from her father’s home. The man, Roy Brown, had been angry about the decision, and later began making harassing phone calls to the office and had mailed several angry letters. As a result, the supervisor had contacted the sheriff’s department, and Roy had been arrested.

When Detective Pickney investigated the supervisor’s report, he learned that Brown had served 8 months in jail for the incident and had been released less than a week before Sabina’s murder. Brown also had a prior conviction and a restraining order put against him on behalf of a previous girlfriend. According to his file, Brown lived in Syracuse, N.Y., roughly 30 miles from Sabina’s house.

With this information, Detective Pickney went to the district attorney’s office and secured a court order to obtain teeth impressions from Brown to compare to the bite marks found on Sabina’s body. When approached by police, Brown did not protest and willingly provided investigators with a bite impression.

The following morning, Brown was awakened by a knock on his front door. When he answered it, he was surprised to see several patrol cars parked in front of his house. He was also surprised to see Detective Pickney standing there with a warrant for his arrest.

When police took Brown back to the station, they told him his bite pattern was a match to the bite marks found on Sabina Kulakowski’s body. Despite this, Brown proclaimed his innocence, maintaining he had had nothing to do with her murder. Unfortunately, his alibi was not very strong: he claimed to have been at home, alone and asleep, at the time of the murder. As a result, Brown was arrested and charged with Sabina’s murder.

Having little money, Brown could not afford an attorney, so the court appointed two lawyers to defend him. When the case went to trial, the defense called an odontologist to the stand, who disputed the bite-mark evidence. It was his testimony that Brown’s teeth were not a match, that there was only one discernible bite mark on the victim’s body and that it did not appear to have come from Brown, who had been missing two upper teeth at the time of her murder.

Despite the defense’s arguments, a jury found Brown guilty of Sabina’s murder, and on January 23, 1992, he was sentenced to 25 years-to-life behind bars.

When Roy Brown arrived at prison, he was depressed and angry; however, he quickly decided that if he were ever going to be free again, he would need to get beyond his feelings and think clearly. Brown had few people to help him on the outside; the only people who believed in his innocence were his attorneys.

Brown began his crusade for freedom in 1995 by filing a motion that a DNA swabbing be done on the nightshirt that Sabina had been wearing on the night of the murder. Unfortunately, he soon learned that all of the DNA evidence in the case had been consumed during the initial tests.

Undeterred by the lack of physical evidence supporting his innocence, Brown spent the next seven years reading textbooks in the prison library. He studied every aspect of his case, and by 2002, with the advances that science had made in the study and collection of DNA, he had found renewed hope. However, that same year he had received some very disturbing news. His stepfather’s farmhouse had burned down, along with all of Brown’s collected court documents. To Brown, this was one of the worst obstacles yet.

Just as Brown was about to give up hope, he came across information concerning the Freedom of Information Act. As it turned out, losing all of his documents was a blessing in disguise, for he learned that not only did he have a right to request all of the trial transcripts, he also had the right to receive copies of all the information that the District Attorney’s Office had compiled on his case.

When Brown received all of the case files the next year, he was shocked to discover that police had initially focused their investigation on Barry Bench, the volunteer firefighter who had discovered the body. The information piqued Brown’s interest, and the more he learned about Bench, the more he wondered why Bench had not been arrested for Sabina’s murder.

Bench had knowledge of the victim; his brother had lived with her for over 17 years, and after their breakup, his brother had left the family’s farmhouse to her, something that Brown suspected had not sat too well with Bench. On top of all that, Bench was the person who had discovered Sabina’s body. Brown couldn’t help but wonder why none of this information had been brought up at his trial and why his lawyers had not been made aware of this.

On December 24, 2003, Brown filed a motion to overturn his conviction based upon the new-found evidence. Unfortunately, his motion was denied and he was returned to his cell at Elmira to determine his next move.

In a bold move, Brown wrote Bench a letter, in which he accused him of Sabina’s murder. Brown also wrote that, with the advances in DNA technology, there was no place for him to hide anymore. Brown later admitted that he was not sure if the tactic was the right thing to do; at the time he still wasn’t 100% sure that Bench was guilty. Nonetheless, he had a gut feeling that he was on the right track, so he mailed the letter and patiently awaited a response.

Five days later, Brown, watching the evening news, learned that Bench had committed suicide. Witnesses at the scene stated that Bench had thrown his body in front of an oncoming Amtrak train. Brown was dumbfounded by the news. He had never wanted to make Bench kill himself; he just wanted his freedom. The incident did, however, convince Brown that Bench was the real killer.

In 2005, Brown was diagnosed with liver disease. However, instead of sinking into a deep depression, he became more determined than ever to regain his freedom and asked the Innocence Project to help him. Known throughout the prison system, the Innocence Project had successfully helped many inmates gain their exoneration and release through the use of DNA technology. However, the group did not take on every case presented to them. One of their guidelines was that they truly believe in the innocence of potential clients. Fortunately, when Brown’s formal request reached their desk, they looked thoroughly into his case and quickly agreed to help him.

The first step in proving Brown’s innocence would be to obtain DNA samples to compare with the samples that were left on the deceased body. They would also need to compare samples to Brown and Bench’s DNA. The biggest obstacle was that Bench was no longer alive. However, the Innocence Project was able to convince a daughter of Bench’s to provide samples. She said she consented to the tests because she needed to know the truth about her father.

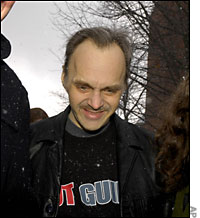

James Vargason

To the amazement of many, the DNA taken from Bench’s daughter was indeed a 50% match to the DNA found on Sabina’s body. Unfortunately, it was not enough to prove that Bench was responsible for Sabina’s murder. District Attorney James Vargason, the man who had prosecuted the case in 1992, felt that the new test results were irrelevant, since it could not be determined that Bench’s daughter was truly his biological daughter.

With pressure being applied on Vargason by the Innocence Project, he agreed that the only way to put the case to rest would be to exhume Bench’s body. Shortly thereafter, a judge order Bench exhumed. Forensic experts then determined that Bench’s teeth matched bite marks found on the victim’s body and that the DNA found on Sabina’s body was a 99.9% match to Bench’s DNA.

In January 2007, Roy Brown, 46, finally walked out of prison a free man. The liver disease had taken its toll on his body, and he appeared understandably bitter when he briefly spoke with reporters.

“This ain’t a miscarriage of justice. It’s an abortion,” Brown said. “That’s what this is. It’s an abortion of justice.

As of this writing, Roy continues to await a liver transplant. Only time will tell if he wins the second battle for his life.