Halloween Murder in Napa Valley — Attack in the Wine Country — Crime Library

Lauren M. noticed the security light come on outside the home she shared with Adriane Insogna and Leslie Ann Mazzara, and, despite her dog’s warning growl, she dismissed it as probably just a cat. She heard other noises, but thought that one her of housemates had invited a boyfriend to go upstairs. The three housemates had given out Halloween candy that evening and had gone to bed around 10:30 p.m., Lauren in her first-floor bedroom in the back of the tract house, and the other two upstairs.

Awakened at 2:00 a.m. by the sound of breaking glass, Lauren heard a struggle in the upstairs rooms. She jumped out of bed and stood listening for a moment near the doorway of her room. A voice cried out from upstairs.

“Please, God, help me! Somebody help me!” The voice was Adriane’s.

Lauren then heard someone rushing down the stairway, and all she could think to do was escape out the back door, leaving her trapped in her fenced backyard. There she hid, listening, as the intruder jumped out the kitchen window in the front of the house and ran away.

Adriane cried again for help, so Lauren went back inside to call 911. However, the cordless phone failed to work, and upstairs she found her friends lying face-down and just barely clinging to life. The floor was a bloody mess, and Adriane was behind her bed, bleeding badly and no longer able to speak. Leslie lay in a pile of clothing, unconscious, with wounds all over her upper body.

Lauren realized she could not save them, and, afraid the intruder might return, she left again, getting into her car and using her cell phone to call 911. A police officer patrolling nearby arrived at the scene, but he was too late. The victims were both dead.

After a quick inspection of the house, the officer concluded the killer had forced open the kitchen window to enter and had then climbed the stairs and attacked the girls, stabbing them repeatedly. For some reason, he had not bothered to search the rooms downstairs. He fled the home by the same route, breaking the window’s glass and leaving behind some of his own blood.

A task force was quickly formed, recruiting law enforcement officers from the Highway Patrol, the Sheriff’s Department, and other police departments near Napa. More than twenty officers combed the neighborhood, looking for anyone suspicious, but they found no one that night to question or arrest. They also found no murder weapon, but at the scene it was clear that the killer had been injured in the struggle and had been bleeding.

News of the crime in the papers the following day, November 1, 2004, stunned area residents. The Napa Valley in Northern California is famous for its many wineries and unique beauty. A tourist destination for millions, it provided resorts, wine tours, and exquisite restaurants. It was not associated with violence, domestic or otherwise, and the Westside neighborhood where the double slaying occurred was considered quiet and safe.

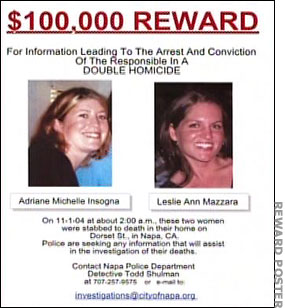

The FBI was asked to help with evidence analysis, and within a few days community leaders offered $100,000 for information leading to an arrest and conviction. Napa police called meetings with residents to reassure them that the attack was unlikely to have been random. Aware of the many single young women who worked in the local tourist industry, they stated they believed the perpetrator knew one or both of the victims, and they asked for assistance. “We want the public to have heightened awareness of any new injuries or change in behavior,” said Napa Police Chief Jeff Troendly, “such as missed work, unplanned vacations, events not attended or any unusual anxiety.”

What no one knew was that the man they sought was mingling among the mourning relatives, consoling them and attending candlelight memorials. None suspected him, and for a while, it seemed that he’d escaped the net.

Because neither girl had known enemies and there were no obvious leads, investigators had to focus on the victims’ backgrounds to try to understand how they had drawn the attention of their killer. Complete research on victims is vital to such work, because some small detail can identify risk factors and potentially dangerous associations. Whether the victim was killed at home, was involved in drugs, was having an affair, had a criminal history, was employed, had domestic problems, or associated with certain social groups are all relevant to developing a hypothesis about how such a crime could have taken place. Even information about associates from the victim’s past can be crucial.

Once information is collected, the detectives map out a timeline to understand the victim’s movements up until the crime. This may cover the day before or perhaps even several weeks before. The victim might have met the killer at a public place where they were seen together, or she might have purchased something where he worked. Perhaps he was a former boyfriend who’d been stalking her. To get a sense of the possibilities, detectives question witnesses and acquaintances. Diaries, letters, phone messages, emails, or any other communications may help, especially if the victim was apprehensive about someone or had just made a new acquaintance.

A victimology is painstaking, time-consuming work, and the quality of the final product depends to a great extent on how cooperative the victim’s family and associates are, and on how much they actually know. Where there are gaps in information, there are possibilities of missing the killer’s identity.

killer’s.

In this case, the detectives were able to collect DNA from the blood at the scene to compare to anyone who might become a suspect. While that, too, can be a painstaking process if the victim has many associates, it can either sift out the perpetrator or spook him into a revelatory mistake. In the very first criminal case in which DNA was used for identification of the perpetrator, the actual perpetrator persuaded a co-worker to take the blood test for him. When police learned this, they knew he was a strong suspect. DNA confirmed that he was the person for whom they were looking. Yet even to begin to eliminate people via DNA meant learning about the victims.

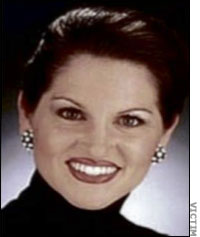

Leslie, winner of the Miss Williamston beauty pageant in South Carolina, had been raised by a single mother on a farm, with two older half-brothers. She aspired to be many things, but she was continually drawn to the wine country. When her mother moved to Berkley, it seemed the right time to seek opportunities there, so in 2004 she applied for and was hired to a position as a concierge and sales representative at Francis Ford Coppola’s wine estate. She enjoyed mingling with celebrities, according to the Los Angeles Times, and hoped she might eventually be discovered and given more glamorous opportunities. At the time of her murder, Leslie was dating two men, and had seen many others during the seven months she’d been in the area. People described her as a “heartbreaker,” and a number of men had bought her extravagant gifts and sought her attention.

young women.

Leslie had found a room in the rental house shared by Adriane and Lauren. Adriane, a local, was outgoing and athletic. She worked as a civil engineer at the Napa Sanitation District. Among the plans in her immediate future was a visit to her sister in Australia. She had a boyrfriend with whom she had had a strained relationship, so he was a prime suspect, although police believed that Leslie had been the more likely target. Adriane had lived a quiet life, while Leslie had been more outgoing and had had a wider circle of acquaintances, especially men.

Strange theories were offered, such as the girls owing someone drug money, or even a Mafia hit. Everyone was trying to help, but there were too many directions at once, none of which was solid. Looking into the victims’ male acquaintances was the first step, but detectives knew if they struck out there, they faced the lengthy process of checking out men who might have encountered them briefly at a party or in a bar. They started with the most accessible candidate first.

A block away from the Dorset Street house was the home of the young man, Christian, who had been dating Adriane for several months. Shortly after the murder, five detectives went to his home in the early hours and roused him from sleep. They asked if he had a weapon, and he said he did. He showed them where it was, and they collected a knife, his bed sheets, his clothes from that day, and samples of his blood. He was asked to come into the police station for questioning.

Christian, seemingly shocked by the news, readily admitted he had seen Adriane the evening before. She had come by to say hello after handing out Halloween candy with her housemates. However, he said, she had left his place around 10:00 p.m. to return home. He also admitted that they had been arguing a lot lately and that things had not been going well in their relationship. She wanted a stronger commitment from him, but he was reluctant to make it. She’d just told him she had met another man, which bothered him, but it was apparently her way of saying that if he could not get more fully involved, she could find someone else.

Although he had been angry at time with Adriane, Christian swore he had never hurt a woman and would certainly not harm Adriane. His reluctance to be more deeply involved romantically was certainly no motive for killing her. Still, Christian remained a top suspect until a DNA test cleared him. His blood did not match the blood found in the residence, and nothing else tied him to the crime.

Adriane’s mother was in Australia at the time of the murder, visiting her other daughter. She could hardly believe it, and returned immediately. She told 48 Hours how Adriane had survived a near-fatal car crash a decade before, and that she had considered the girl charmed. In fact, her impressive perseverance during her recovery had earned her a scholarship to California Polytechnic, where she had received her degree.

Among Adriane’s close friends was a woman named Lily Prudhomme. They often went places together and had even planned a vacation to Australia. Since Lily was engaged to the man with whom she had been for eight years, Adriane would talk with her about her romantic troubles. After the murder, Lily expressed frustration that the killer was not quickly caught. “Someone must know something,” she said. She believed his behavior had to have been obvious to anyone who knew him. She hoped that in the struggle Adriane had at least hurt him.

As police processed the crime scene and reconstructed what had happened, the evidence seemed to indicate that Leslie had been stabbed first. That supported the idea that she had been the target, with Adriane just in the wrong place at the wrong time. From the blood spatter pattern analysis, investigators were able to see how the participants had moved around. Leslie, it seemed had not made it far from her bed.

Interpreting blood spatter patterns is a both a science and an art, based on experience and interpretive ability. As a liquid, blood obeys the laws of physics and when force is applied to a body resulting in a spray of blood, the amount that sprays, the shape of the drops, the angle of impact, and the final location of a spatter will indicate a number of things: the blood’s velocity, the type of weapon used, and even how many people were involved. The greater the force striking a person, the smaller the size of the spatter. Blood with more weight travels farther, but eventually it all curves downward if it doesn’t impact somewhere, impelled by gravity.

Reading bloodstain patterns helps investigators figure out the positions of victim and attacker, and the stages by which they moved around, interacted, and struggled. Once the events are reconstructed, investigators can more effectively look for fingerprints, trace evidence, footprints, hair, and fibers. The assessment of bloodstain patterns will also limit the need to collect an overabundance of blood samples for DNA, and an accurate reconstruction helps determine if a witness or suspect is telling the truth.

The shape of the blood drop can also yield important information. The proportions reveal the energy required to disperse it in those dimensions, while the shape of a bloodstain can illustrate the direction in which it was traveling and the angle at which it struck a surface. Choosing several stains and using basic trigonometry enables the crime scene processor to devise a three-dimensional recreation of the area of origin from which a blood-letting event occurred.

was found.

In the Napa attack, there had been an attacker and two victims, who had been sleeping in adjoining rooms. The attacker had been wounded and lost blood, as did the victims, and identifying the three different blood types showed exactly where each person had been when wounded, and where they had gone from there. It appeared that Leslie had taken the first blow, attacked while asleep, but she had ended up face-down on a pile of clothing near the bed. Adriane appeared to have struggled with the attacker, possibly trying to save her friend before she finally drove him out and succumbed to her wounds. Along with the blood pattern evidence, Adriane showed a lot of bruising and defensive cuts on her hands.

Although Lauren grew terrified for her safety when the killer was not quickly apprehended, she realized that, as the only witness, she had a responsibility to her former housemates. She agreed to go on the television program, America’s Most Wanted, to talk about her terrible experience, and she went on other shows as well. She asked that her face be disguised or hidden, but she boldly told her story, hoping that someone in the viewing audience would see it and reconsider what they remembered from that night. Perhaps refreshing the details would shake something loose.

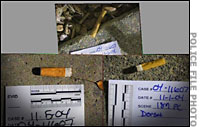

Yet as the months progressed, all substantive leads dried up and it was beginning to look as if the crime might not be solved. DNA evidence from blood found at the scene indicated that the perpetrator was a male Caucasian, and cigarette butts picked up outside were determined to have come from Camel Turkish Gold cigarettes, a brand only recently released. Since it was a distinctive brand, it would be easier to use to confirm a suspect whenever the police developed one. In addition, the DNA from intruder’s blood matched DNA from saliva on the cigarette butts. However, the police did not disclose these facts to reporters and would later endure criticism for this. In retrospect, the information could have identified the killer right away, saving grief and resources.

blood evidence on stairs.

Over the course of a year, investigators conducted over 1,300 interviews in eight different states of people who had known the victims, as well as of residents from the area. They collected 218 voluntary biological samples for DNA analysis from men who’d had contact in some manner with the victims.

Yet it was not until August, nearly a year after the incident, that the police decided to release more information. To reporters they stated that the killer was probably a chain-smoker who had stood outside the house awaiting his opportunity. They revealed the brand of the cigarettes, thinking that someone would know a person who smoked it. Lauren recalled that Eric Copple, the husband of Adriane’s best friend, Lily, had smoked. He had also been in the house on at least one occasion. She called the police to tell them.

They placed calls to him and his wife, but none were returned. A month went by, and they still had not spoken with him or collected his DNA. Lauren was not sure why. Finally, on a Tuesday night in September, Eric Copple, 26, arrived at the police station, in the company of his parents and his wife. He spoke with detectives for five hours, after which they told reporters he had made incriminating statements that they viewed as tantamount to a confession.

Copple was charged with two counts of felony murder, with special circumstances that made him eligible for the death penalty: two murders committed in the same time frame, as well murder committed by the use of a knife.

Reporters quickly dug up information revealing how Copple had known the victims. He had once worked for a Napa-based engineering firm that included among its clients the Napa Sanitation District, where Adriane had been employed for three years. This company had even donated money to the investigation’s reward fund and for a scholarship that honored the victims. Copple had left the firm a year before the murders, but he had retained an association with Adriane because of her close friendship with his then-fiancée, Lily Prudhomme. He had even been present at the Dorset Street house when Adriane and Lauren had first rented it. While Eric’s name had cropped up during the investigation, he had not been seriously considered a suspect. The police did not even collect a sample for DNA testing.

Three months after the murders, Lily married Copple, and Adriane’s mother attended their wedding, reading scriptures in honor of her daughter. She was stunned when she learned Copple had been arrested. “I never felt he was dangerous,” she said. “I never felt a sinister vibe from him.” However, some acquaintances of Copple, speaking to reporters, described him as unfriendly and inconsiderate, and one neighbor even called him an “odd duck.” Everyone agreed on one thing: he was a chain-smoker. In fact, he smoked the brand for which the police were looking.

At the October 14 arraignment in Napa County Superior Court, Copple pleaded not guilty to the charges. Chief Deputy Public Defender Ralph Abernathy was appointed to represent him, and District Attorney Gary Lieberstein told reporters that it was too soon to decide if this would be a death penalty case. Copple was held without bail at the Napa County Detention Facility, and a November date was set for his preliminary hearing. To the frustration of many, the hearing was delayed several times.

To this point, the police had remained mum on the motive for the slayings, but said that Copple’s family had pressured him to turn himself in. From the phone calls left on his answering machine, he was already aware that the investigation had finally targeted him, and he allegedly left a suicide note admitting to the murders, which his brother found. Copple apparently alluded to the fact that he’d been jealous of Adriane’s close relationship with his wife. The brother persuaded Copple to talk with the police, and he turned over the note when they arrived at the station. His demeanor, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, was “subdued” and “despondent.” His wife had been by all indications completely unaware of his involvement, despite her prior belief that the killer would be obvious to those who knew him, and she was not charged with anything.

In response to questions about why Copple would have killed the girls, the district attorney said, “We are still trying to understand what led up to this tragedy. Although the motive is a human interest side of this story, it is not an element of the crime. Sometimes people do unthinkable things and we never know why.”

The preliminary hearing finally got underway in mid-May 2006. Lauren once again went over the events of that gruesome Halloween night, and then Napa Detective Todd Schulman described how the investigators had found a small area of blood by the broken kitchen window and two cigarette butts in the yard nearby. He also told how the search, after a massive voluntary DNA dragnet, had led to Eric Copple. Copple had then told police that while he knew he had killed them, he did not remember any details about the violence. He told police he had gone to a party that night and got drunk. His fiancée had driven him home, where he had blacked out. Later he had woken up, retrieved a knife and some “zip ties” from his garage and driven over to Dorset Street. He had said he did not know why he had taken either of these items, or why he had gone to the house.

He recalled smoking a cigarette near the garage, where a security light had come on, and then using the knife to pry open a window. He had gone in, climbed the stairs to the room where he knew Adriane slept, and lain down in a pile of clothing. Adriane had woken up and turned on the light, startling him, so he had jumped onto the bed. He had thought she or someone else had hit him in the face, and, he claimed, had blacked out again. He then had heard a sound from the other bedroom so he had gone there. He claimed he had his eyes closed and did not recall attacking anyone. He could not recall anything that happened after that, except that he had ditched the knife and then had burned his clothing in his own backyard.

Having heard the account of Copple’s recollections to police, Napa County Deputy District Attorney Mark Boessenecker then described how the DNA from the blood near the kitchen window had been matched to saliva from the cigarette butts and skin cells on flex bands, all of which had in turn been linked definitively to Eric Copple. There was also blood from him on a wallboard and on window blinds in the house.

Copple’s defense attorneys did not question that the DNA was his or that he had been there, but they presented a mental illness defense. Their questions at the hearing suggested that they planned some form of diminished capacity defense. At the time of the murder, he may have been depressed and suicidal, and his apparent memory loss could help mitigate the crime.

Boessenecker argued that the defense’s version of events contradicted the physical evidence, which indicated careful preparation and surveillance, not a half-drunk idiot who had stumbled into someone’s home. He had brought flex ties and a knife, he had stood outside smoking, he had jimmied a window, and then got rid of the evidence. He had known what he was doing.

Regardless of the interpretation of the evidence, they all knew they faced a long and expensive trial.

Copple’s attorney’s held extensive meetings with family members of the victims and worked out a deal that would allow them to avoid the stress and grief of a lengthy legal proceeding. Some of them felt that justice was not done, but they also did not wish to relive their pain from the past two years.

Accordingly, on December 6, 2006, Eric Copple, dressed for court in a white shirt, black suit and black tie, pleaded guilty to killing Leslie Ann Mazzara and Adriane Insogna. In exchange for the plea, he received a sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole. He agreed to waive his rights to appeal at all levels and not to speak to the media. If Copple ever violates the deal, his sentence could be reviewed, and he could instead get the death penalty and also be liable for $10 million in wrongful death benefits to the family members and victim memorial funds.

In court, Copple admitted that he did lie in wait outside the house that night, he entered it by using a knife to pry the window, and he did stab both women to death. Aside from the rumored admission of jealousy in the suicide note, whose precise contents remain undisclosed, his motives for this outrageous crime remain a mystery.

Cabanatuan, Michael. “Evidence in 2 Killings sent to FBI Crime Lab,” San Francisco Chronicle, Nov. 12, 2004.

Dorgan, Marsha, “Eric Copple Accused of Killing Two Napa Women in 2004,” Napa Valley Register, May 11, 2006.

—”Even after Arrest, Families Struggle with Halloween Night Double Homicide,” Napa Valley Register, November 1, 2005.

—”Copple Pleads Not Guilty,” Napa Valley Register, July 13, 2006.

—”Copple Admits Guilt in Double Murder,” Napa Valley Register, December 7, 2006.

Doyle, Jim and Matthew B. Stannard, “Arrest Made in Fatal Stabbing of Two Women,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 17, 2005.

—Charges in Slaying of 2 Women,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 30, 2005.

—”Man Held in Napa Valley Roommate Murders,” San Francisco Chronicle, Sept, 28, 2005.

Gafni, Michael. “Family Pressure Brings in Suspect,” San Francisco Chronicle, Sept. 30, 2005.

LaRosa, Paul. Nightmare in Napa: The Wine Country Murders, CBS 48 Hours Mystery paperback, based on television episode that aired November 19, 2005; Pocket Star, 2007.

“Nancy Grace” transcript, September 30, 2005.

Podger, Pamela. “Link Seen between 2 Victims and Killer,” San Francisco Chronicle, Nov. 6, 2004.

“Sole Survivor of Napa Killing Speaks,” ABC News, October 7, 2005.

Tempest, Ron. “Suspect Consoled Families,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 2005.

—”As it Mourns, Bucolic valley Also Knows Fear,” The Los Angeles Times, November 15, 2004.