LA Forensics: The Keystone Diamond — Awakened in the Night — Crime Library

EDITOR’S NOTE: Some of the names in this story have been changed to protect their identities.

STUDIO CITY — It was shortly after midnight on Oct. 16, 1983, and Dennis Brown was getting ready to go to bed. He said good night to his roommate, William Conway, and retired to his room. By all indications, it seemed like just another quiet night in Studio City, an upper middle class bedroom community north of Hollywood.

The pair had met during a stint in Alcoholics Anonymous, and William, who was going through a divorce, asked Dennis if he wanted to rent a room. Studio City was a great place to live — close enough to Hollywood to feel like you’re part of the action, yet far enough away to escape the seediness and the crime.

For Dennis, it was also close enough to find a wide array of women to bring home, something the 70-year-old William didn’t like. The men constantly argued about the women.

At 2:30 a.m. Dennis awoke to noises — possibly voices — coming from William’s room, so he got up to investigate. Dennis started to open William’s bedroom door to see if he was all right, but someone on the other side pushed it closed.

“William?”

No response. Strange.

Concerned, Dennis went into the kitchen and picked up a knife. William’s bedroom also had a sliding glass door that led into the backyard and Dennis was going to look through it to see if anything was amiss.

William’s attack-trained German shepherd, Dante, was outside; the sliding door was open so the dog could come and go at will. In the darkness, Dennis could barely make out William getting up from his bed and falling down on the floor with a groan. William might have been drinking, Dennis thought.

“Are you okay?” he called out.

“Yes, I’m okay,” a voice answered.

Satisfied, Dennis returned to his room, leaving Dante in the backyard.

Shortly after returning to bed, Dennis heard the sound of a car backfiring. He went back to sleep. Around 8:30 the next morning, Dennis went to check on William to find out what had happened the night before. A horrific sight greeted him.

William was lying on his left side on the floor near the door, where Dennis had seen him the night before. Blood covered his head. His face looked like it had been used as a punching bag. He was obviously dead.

A medical examiner would do an autopsy the following day and find that William had been shot three times in close proximity behind the right ear. The killer had been standing so close that the wound area was covered with smoke, soot and stippling. In addition to a smashed nose and cut up face, William had bruises and abrasions on his neck, shin, right elbow, right hand and both shoulders.

Someone had beaten William senseless and then wanted to be certain he’d never live to talk about it. One witness had seen the whole thing and he wouldn’t be saying anything. Dante had let the attack happen without even a single bark.

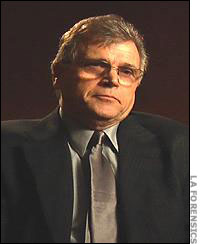

Los Angeles police Detective Richard Ramsdell would start looking for a suspect among those in William’s inner circle, because they would also know the dog.

“There’s not a yelling or screaming for assistance,” Ramsdell said. “That dog didn’t attack anybody. I believe the victim would’ve called out, be more in fear of his life, if an intruder unknown to him would have been in that room.”

William had worked hard to make a living as a car salesman, and he had done a pretty good job of it. Many people in that business scraped by, living in apartments and going job to job. William had a single story house with a pool in an artsy Studio City enclave that is home to professionals in the entertainment business. You wouldn’t have to look hard to see comic Jay Leno, for example, riding in one of his vintage cars down Ventura Boulevard, the main drag in Studio City.

Although William wasn’t nearly as wealthy as some of his famous neighbors, he liked to pretend that he was. Every day he wore a large diamond pinky ring, a Rolex watch and a gold chain, giving the impression that he had lots of money. It was all part of the façade of selling cars in Los Angeles.

But with the pretentiousness of being well off came the inevitable battles over money: a pending divorce with a wife who wanted more of his assets than he was willing to give; a nephew who sued him over some sort of a land deal, claiming he didn’t get his fair share; and a 19-year-old grandson with a drug problem who wanted money and a free college education. His grandson, Noel Scott, lived with William for a few months shortly before the murder. William refused to pay for the tuition, saying he said he couldn’t afford it.

One thing was for sure — Ramsdell didn’t have a shortage of suspects.

A growling Dante greeted Detective Ramsdell as he arrived at William’s home with LAPD criminalists. Roommate Dennis corralled the animal so the investigators could begin the arduous task of collecting evidence.

The bedroom was fairly small and didn’t appear to be ransacked. In fact, it was pretty orderly, which led detectives to surmise that William probably didn’t put up much of a struggle. He was lying on the floor wearing just a pair of swimming trunks, his head on top of gray sweatpants. Three bullet casings were found near his body. And when the coroner took William away, detectives found a bullet under his head. This meant that William was already on the floor when he was shot; otherwise, the bullet would have ricocheted.

Ramsdell continued to look around the room and videotaped everything. Blood appeared to be contained to the area where William collapsed. A bullet hole was evident in a ceiling corner. Hundreds of hairs were in the room: they could belong to William, the dog, Dennis, or any family member. Criminalists collected a good sampling of hairs and some bloody carpet samples. A jewelry box filled with costume jewelry was on the dresser, but it didn’t contain William’s ring, watch or chain. In fact, those items weren’t found anywhere.

Detectives opened a drawer in a nightstand next to the bed. It contained an empty holster and .32 caliber ammunition, but no gun. The bullet casings on the floor matched the ammunition so it was likely that William was shot with his own gun, which was nowhere to be found.

Criminalists didn’t find any fingerprints on the sliding glass door, but they did lift some from the front door. A shoeprint on the patio just outside the patio door was photographed for comparison to a future suspect.

The best clue of all was a red flashlight, with a bloody fingerprint, lying on the floor in the closet. It was still turned on. Whoever had done this had left a calling card, but detectives would learn that making an arrest was going to be quite another matter.

The last to see a murder victim alive is usually the first to be questioned. Then detectives fan out from there to include lovers, family, friends and colleagues. It’s no secret that most murders are committed by someone within the victim’s personal orbit. If one included all the women Dennis brought home, that list could become pretty long indeed.

Dennis recounted his version of events. Ramsdell was suspicious of claims that he heard a car backfiring — anyone within such a close range would have figured out it was a gunshot, he mused.

“The victim’s roommate could’ve been out drinking that night (but) he didn’t admit to it,” Ramsdell said later. “However, it could’ve been that he didn’t hear the gunshots but he admitted that he heard cars backfiring.”

In order to prove this, Ramsdell had forensic investigators prepare an audiotape of three .32-caliber gunshots going off. The tape was played in William’s room while detectives stood in Dennis’s room and out on the patio. There was no mistaking what it was.

“He’s a prime suspect in the first few days of this investigation,” Ramsdell said later.

Another thing that Dennis failed to mention was the string of female guests he entertained. Witnesses in the neighborhood reported seeing a woman running from the house with torn clothing the night of the murder.

Dennis was taken to the police station for a polygraph test. The results were inconclusive, meaning that the test didn’t prove he was innocent, but certainly didn’t point to his guilt either. None of Dennis’s shoes matched the shoeprint found at the scene. Time to start looking at the relatives.

Ramsdell wanted to talk to the ex-wife. She and William had fought over ownership of the house and another piece of property, resulting in an ugly divorce situation. Mrs. Conway was also one of the few people who could have walked past Dante without a fuss. She was given a polygraph test and passed.

Detectives also talked to the nephew, a sister, a stepdaughter and numerous other people. They fingerprinted all of William’s relatives and friends to compare with the prints found in the house and on the flashlight. Back in 1983, no computerized fingerprint database existed. Forensic investigators had to manually compare lifted prints with identified suspects. It was a cumbersome process.

Witnesses gave the detectives some valuable information — every night before bed, William took off his pinky ring, Rolex and gold chain. He placed the items on a nightstand next to his bed, not in the jewelry box.

“A normal burglar would have scooped up everything,” Ramsdell thought. “You’re not going to sit there and appraise the jewelry while you’re doing this crime. So whoever went there knew exactly what they were going to pick up.”

The detectives still needed to interview two others: Noel Scott, the grandson; and his childhood friend Mario Lombardi, a frequent visitor well known to William. Their fingerprints were already on file because they had committed petty thefts together. It seemed that they were crime partners as well as best friends.

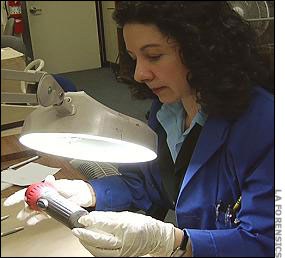

Meanwhile, back at the crime lab, criminalists went to work on their evidence. The hairs were checked out under a microscope and found to be either William’s or Dante’s. The dark red matter on the flashlight, carpet and sweatpants was found to be consistent with William’s blood. DNA was not being used yet, so the best scientists could do was match the blood by type.

The shoeprint hadn’t come back yet to any footwear worn by the people detectives had interviewed.

Criminalists were more successful with the fingerprints. One on the outside of the front door matched roommate Dennis. A palm print on the door’s inside belonged to Lombardi.

The flashlight was next. Criminalists couldn’t dust the outside because it had an uneven surface and wouldn’t yield a good result, so a more intricate procedure was required. The flashlight was placed in a glass chamber that contained a small bowl of superglue and the chamber was heated. Glue fumes adhered to the prints left by a bloody left thumb and middle finger. A UV light was used to view the prints; then they were photographed for comparison.

They belonged to Noel Scott.

In California, pawnshop owners are required to obtain valid photo identification for anyone who wants to sell an item. It’s a good tool for police who are looking for stolen items. Ramsdell periodically ran his list of subjects through the local pawnshops, hoping for a hit.

Three weeks later it happened. A pawnshop reported that Lombardi brought in a diamond. William’s widow was brought in to the shop and confirmed that the stone came from William’s ring. William’s longtime jeweler was shown a photograph of the diamond and recognized it immediately because of its European cut and great clarity.

The pawnshop owner said a young man initially came in with the stone but left when he was asked for identification. The next day, another person showed up with the diamond. Identification showed that he was Lombardi.

Detectives talked to Lombardi. He admitted going to the pawnshop, but said Scott gave him the diamond to sell with the deal that they would split the proceeds. Suddenly, it seemed that either Lombardi or Scott could have committed the murder, or maybe the two of them together. Lombardi had certainly been at the house often enough to get past Dante.

He was given a polygraph test that came back inconclusive — meaning that he wasn’t proven innocent or guilty.

Detectives focused on Noel Scott, a struggling actor and musician who just couldn’t seem to make it in Hollywood. Credits listed on his resume included stints on the television shows Eight is Enough and King’s Crossing. But he had a cocaine problem and fell on hard times in 1983. William let him move in for a while and lent him money, witnesses told police.

His home was searched but detectives didn’t find a matching shoeprint. Scott was then interviewed and made less than a spectacular impression.

He denied going into the pawnshop, but when pressed, admitted trying to sell a diamond that belonged to Lombardi. As for the night of the murder, he had no alibi.

“Oh, I’m home watching TV,” Scott told detectives. As the interview wore on, the locale changed to a nightclub.

He denied ever going into William’s closet, even though the flashlight with his fingerprints was found there. Detectives knew Scott had a close bond with Dante and asked about that.

“I don’t understand how anyone could have gone around, the dog must have been drugged,” Scott replied.

What a strange thing to say, detectives thought. The dog gave no indication of being drugged after the murder. Who would think of doing such a thing?

During the interview, detectives noticed Scott’s fingertips. It looked like they had been sliced in a criss cross manner with either a knife or razor blade.

“I was working on my car,” was his explanation.

Ramsdell knew there was nothing under the hood of a car that could extensively cut one’s hands.

“It implied to us, as investigators, that he was trying to hide his fingerprints and that he had knowledge that his fingerprint was on that flashlight,” Ramsdell said.

The interview frustrated detectives because Scott either refused to answer questions or gave answers that made no sense. Then he refused to take a polygraph.

They didn’t have enough to hold him and let him go.

“The suspect’s lack of alibi is hard to work because you can’t prove or disprove his statement,” Ramsdell said. “He puts himself nowhere and with no witnesses.”

It wasn’t long before police had another run-in with Scott. This time he walked into the station of his own accord, blaming Lombardi for burglarizing his apartment.

“I want him arrested,” Scott said.

Lombardi had wiggled out of the pawnshop episode and now he was in trouble again. So when confronted by the detectives, he decided to level with them. Yes, he broke into Scott’s apartment and took some items. However, it was only because he didn’t receive his fair share of money for trying to pawn the diamond, he said.

Lombardi wanted to ensure the detective’s good will by giving them some dirt on Scott.

In a local park after a few days after the murder, Scott asked Lombardi: “How do you alter your fingerprints?”

“You slash them. You alter ’em by slashing them,” Lombardi replied.

Scott also asked how to beat a polygraph, Lombardi revealed.

This additional information was interesting and it made Scott look guilty, but it wasn’t enough for an arrest. Lombardi’s statements could be viewed as suspicious because of his prior arrests. Detectives had nothing more to go on and the case languished.

“The stumbling block in this investigation, why this case went cold, is we had no witnesses that could put the grandson at the scene of the crime,” Ramsdell said.

The case sat on the shelf, one of hundreds of unsolved murders with viable suspects but no ironclad proof.

Five years later, in 1988, Lombardi was arrested again for another burglary. Giving police information on Scott kept him out of trouble the last time; maybe it would work again. He asked for a deal in exchange for giving up more information. The DA agreed to charge him with two burglaries instead of five, resulting in a maximum of three years in prison.

Lombardi told police that several days before William’s murder, Scott talked about wanting to steal his grandfather’s jewelry. Scott was angry that William wouldn’t pay for his college tuition and he felt entitled to the jewelry.

Lombardi reiterated his information from years ago — that Scott came to him several days after the murder asking how to alter fingerprints and beat a polygraph. But there was more. Scott also confessed at that time, Lombardi said.

“I ripped off my grandfather and had a little problem,” Scott told Lombardi.

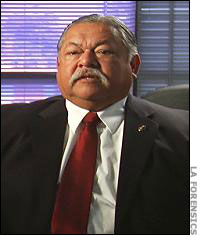

The case was reopened. Ramsdell no longer worked homicides at the North Hollywood station, so Detective Ray Hernandez decided to look into it. Hernandez was a very tenacious detective, someone who had a reputation of delivering the goods required to make a strong case. Prosecutors loved him.

“My partner and I opened the unsolved murder book and delved into it with both hands and feet,” he said later. “Our suspect was a grandson. To me, a grandson and a grandfather…that doesn’t sit well with any normal person so that just gave us more energy.”

The first thing Hernandez did was view the video of the crime scene. Then he reinterviewed all of the witnesses and subjects. This didn’t come as a welcome event in Scott’s life.

“There were a few obstacles,” Hernandez recalled. This was primarily Scott’s mother, who vigorously defended her son, citing her family’s strong religious background.

Scott was still extremely uncooperative when detectives interviewed him. He crossed his arms and legs, obstinately refusing to divulge anything.

Hernandez wanted to know where Scott was at the time of the murder.

“At a coffee shop,” Scott answered. This was the third alibi he had given since 1983.

“Were you ever in your grandfather’s closet?”

“No.”

“Did your grandfather have a gun?”

“I knew he had a gun, but I never saw it.”

While this exchange was going on, Scott’s mother was at the front desk, raising hell.

Hernandez wanted to know how Scott’s fingertips got chopped up. That answer was still the same. Working on his car. Nothing was going to come of this interview and Scott left the police station again, a free man.

Two things were done this time around that hadn’t been done during the initial investigation.

The first was a comparison of Scott’s fingerprints before and after the murder. Then, the altered prints were run through a computer system that was not available in 1983. It filled in the missing part of the print and was an exact match to the prints on the flashlight and to Scott’s first set of fingerprints.

Secondly, Hernandez wanted a better time frame of when the murder happened, so he asked the criminalists to put new batteries in the flashlight, turn it on, and watch to see how long they lasted.

The batteries lasted about 3-1/2 hours, meaning that the crime couldn’t have happened earlier than 5 a.m. Either roommate Dennis really did hear a car backfire at 2:30 a.m. or he was mistaken about the time.

Hernandez drove from the coffee shop of Scott’s alibi to William’s house. Scott could’ve easily been there shortly after the murder but no one working there remembered anything.

It was time to get the district attorney involved.

“Ray had a long history of putting together difficult cases,” said Los Angeles County Deputy District Attorney Sidney Trapp. But more evidence was needed before filing the case.

“I think it would be really taking a chance with a jury if you only thing you had was a thumbprint, which could’ve been put anytime on the flashlight,” Trapp said. “I would not want to go to a jury with just a thumbprint on a flashlight.”

Through witnesses, Hernandez had located an ex-girlfriend of Scott’s, in Phoenix. Trapp thought she could be the key — he’d obtained valuable evidence from girlfriends in past cases.

“I told my boss that I would file the case if he put two tickets on my desk to Phoenix for the next morning,” Trapp said.

Sure enough, the next day Hernandez and Trapp knocked on the door of Sarah Hull in Phoenix.

A pretty woman answered.

“Well, I figured you’d get to me sometime,” she said.

Hull invited the men inside. She planned to eventually contact police as a concerned citizen, she said.

“Why did you think we’d get to you sometime?” Trapp asked.

“Well, because of the gun,” Hull replied.

“What gun?”

“The grandfather’s gun.”

“What do you know about the grandfather’s gun?”

Hull went on to say that three weeks before the murder she and Noel Scott were in William’s room when the older man was out of the house. Scott was searching for a will and opened the jewelry box, marveling at its contents, until Hull told him it was worthless.

Scott was furious.

“He was very angry that he thought he would go to college and he thought his grandfather would pay for it and his grandfather didn’t pay for it because he didn’t have the money,” Hull said. “That he was going to inherit all his jewelry, not knowing that it was costume jewelry, made him even more angry.”

Then Scott opened a nightstand drawer and pulled out a .32 caliber handgun.

“Look what I found,” he told her. As he fumbled with the gun, it discharged and created a bullet hole in the ceiling.

A week later, Hull broke up with Scott when he proposed to her. She felt he was “a bit of a loser” and had no future prospects. Scott said his financial problems would be over when he inherited his grandfather’s estate.

Trapp and Hernandez asked her what she thought of the murder.

“If anybody were to have killed the grandfather, it would be him,” she replied.

The case was solved. Hernandez believed that Noel Scott entered William’s bedroom while the older man slept and grabbed the flashlight to find the jewelry on the dresser. William awoke and the pair struggled. When Dennis viewed the scene from the patio and asked if William was ok, William answered while hiding in the closet. Dennis went back to bed and William was shot.

In February 1989, Trapp filed the case. Scott was living at his grandfather’s house when Hernandez arrived to arrest him.

“The day my partner and I handcuffed him and told him, ‘You’re under arrest for killing your grandfather,’ he didn’t resist. He didn’t argue. He put his hands behind his back and dropped his head on his chest. Yes, he thought he’d gotten away with this,” Hernandez said later.

During the arraignment, Scott was allowed to post a $50,000 bond and he went back to his grandfather’s house. His freedom would be short-lived. His trial began the following January.

Lombardi was called as a prosecution witness and testified that he had lied to police regarding Scott’s confession in order to get a plea bargain for his burglaries. But Lombardi stood by his earlier statement that Scott asked him how to alter his fingerprints.

Hull testified also, a credible and deliberate witness. Then a squirming Scott took the stand in his own defense. He claimed to be at a Hollywood nightclub when the shooting happened, denied knowing anything about the murder, and said he never touched the gun.

In the end, jurors didn’t believe him. After a day of deliberations, Noel Scott was convicted of first-degree murder and later sentenced to 27 years to life in prison.

It was a great moment for Hernandez, who mentally pictured himself shaking William’s hand.

“I felt good for the grandfather,” he said. “I felt good for all grandfathers.”