|

Analyzing fingerprints was the first method that identified a

unique personal signature for each individual, the details of which

remain the same from childhood to old age. Whenever we touch

something, we leave a residue of oil, grease, dust, or sweat that

forms from the imprint of our fingers, and that can place us at the

scene of a crime. (Unless, of course, some wily criminal has

lifted your print from something you touched and placed it at the

scene.)

|

|

Sirhan Sirhan

(AP) |

It was a fingerprint that revealed the identity of the man who

had assassinated Senator Robert F. Kennedy. Sirhan Sirhan

would not give his name, but his prints gave him away. Many

other cases have been solved with fingerprints, and fingerprint

identification has become one of the primary tools for solving

crimes. |

|

The first person to classify fingerprints was Prussian professor

Johannes Purkinje. In 1823, he described nine basic types.

Then in 1858, William Herschel recognized the individuality of

fingerprints and used them for contracts for illiterate workers,

while physician Henry Faulds soon discovered that prints could be

made visible with powders. He used this in a criminal case to

free an innocent man.

Other scientists found that fingerprints were unchanging over

time, and Sir Francis Galton proposed that all prints had three

primary features: loops, whorls, and arches. From these he

could devise 60,000 classes. Edward Henry added two more

features---tented arches and loops that were either radial or

ulnar---and developed a classification based on these five types

that is still in place. One had to first establish to which of

these classes a print belonged and then to sub-classify it by

distinct deltas (the formation of ridges).

In 1894, the British examined fingerprint classification as a way

to replace the slow and impractical method of "bertillonage,"

which identified criminals via eleven body measurements. In

one case in the U. S., the measurements failed to distinguish

between two criminals who were identical twins, but their

fingerprints were dissimilar. This case brought fingerprinting

into its own as the leading tool for identification.

In 1910, Thomas Jennings was the first person in the United

States to be convicted with fingerprint evidence. When he

broke into a home and shot the homeowner, he left four clear prints

in wet paint. The conviction was appealed, but the appeals

court was satisfied that fingerprinting had a solid scientific

basis.

In order to make a comparison match, ink pads were used to take a

suspect's prints. The prison systems quickly adopted this in

order to keep on file fingerprints of known criminals. By

1924, Congress had established a national depository of fingerprint

records at the FBI, and today there are several hundred million sets

of prints there.

How it works

|

|

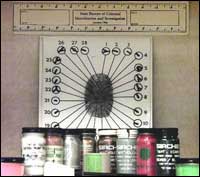

Print chart and powder in

crime lab (AP) |

The surface of the skin on the palms of the hands and soles of

the feet differs from the skin on the rest of the body, in that it

is covered with ridges with clearly defined patterns. The way

these ridges lie gives us our individual marks. |

|

Fingerprints can be latent, visible, or molded (plastic).

- Visible prints are left in some medium, like blood, that

reveals them to the naked eye.

- Plastic prints are indentations left in pliable objects such

as soft wax that take the impression.

- Latent prints are formed from the sweat from sebaceous glands

on the body. They can't be seen, except under certain lighting,

but can be raised to visibility with various methods.

If left on a hard surface that remains undisturbed, prints can be

permanent. Often prints are only partial, but may still show a

sufficient amount of the fingertip surface for point-by-point

identification.

The crime scene investigator's job is to locate latent prints,

develop them, and preserve them. Developing latent prints so

they can be seen involves powders or fuming with compounds

like ninhydrin or Super Glue. Then the prints are preserved on

a card for identification, and marked for the time they were lifted

and the location in which they were found.

This involves using a powder appropriate to a particular surface,

usually in a color that contrasts with the color of the surface.

The powder adheres to the print, so when a fine brush is used to

remove excess powder, the print shows a clear pattern. It's then

photographed, and if it's on a portable object, the whole object is

taken to the lab. Otherwise, the print is lifted with

transparent tape and placed on the index card. This method is

still in use, although other methods have been developed as

well---especially for surfaces that don't respond to powders.

|

|

FBI expert examining

fingerprints (CORBIS) |

To compare them, the print technician must first make sure that

prints are taken of everyone who was at the scene or might have been

there (if possible). That includes taking them off any dead

bodies. To take a print at a scene, an ink roller is run over

the fingertips and the tips are then pressed against a card.

At the police station, the person dips his fingers into printer's

ink and then presses them onto a card. Then each handprint is

inked and preserved in the same way. That provides the

database to which they're sent a set of ten distinct prints, along

with the size of the hand and the shape of the palm. |

|

Since 1972, fingerprints have been compared and retrieved via

computer. By 1989, they could be sent back and forth online.

State and local agencies built up automated fingerprint

identification systems (AFIS), and the FBI opened the National Crime

Information Center (NCIC), which expedited the exchange of

information among law enforcement agencies. They introduced a

standard system of fingerprint classification (FPC), so that

information could be uniformly transmitted from one AFIS computer to

another.

The computer scans and digitally encodes prints into a geometric

pattern according to their ridge endings and the branching of two

ridges. In less than a second, the computer can compare a set of ten

prints against a half million. At the end of the process, it

comes up with a list of prints that closely match the exemplars (the

originals). Then the technicians make the final determination,

which involves a point-by-point comparison. (Before computerization,

searching manually through print files was an arduous,

time-consuming task.)

The patterns for fingerprints, formed by the ridges, are

classified into four basic groups:

- Arches: formed by ridges running from one side to the other

and curving up in the middle. Tented arches have a spike

effect. About five percent of people have this print.

- Whorls: Thirty percent of prints form a complete oval, often

in a spiral pattern around a central point.

- Loops: These have a stronger curve than arches, and the

ends exit and enter the print on the same side. Radial

loops slant toward the thumb and ulnar loops toward the other

side (which makes it important to know from which hand the print

came). This comprises about 60 percent of fingerprints.

- "Composites" intermix two of the other patterns,

while "accidentals" form an irregular pattern.

Once prints are classified and sub-typed, they get stored in the

database for future comparisons.

Other types of physical evidence have classification systems and

databases as well, but evidence alone does not make a case.

Whatever the technicians find must support a theory about the crime.

Let's look at how that's derived.

|

|

|