|

Before he begins sculpting, Bender gathers as much visual

information as he can about the subject. Most helpful is a

succession of photographs that will indicate how the subject has aged.

He can also get the fine details he needs to create a genuine

likeness, adding elements such as moles, chest hair, tattoos,

freckles, and scars. He also wants any clothing found with a

body, if that's what he's working with, and all the pathology reports.

|

Sculptures and photos

(the

author) |

|

|

He reads the reports over and over as the image forms. “I want to

know everything. Something may seem insignificant, but in the

end, it may play an important part. You just lose yourself in it,”

Bender said.

Then he studies the skull. Sometimes it arrives clean and

ready, and sometimes he has to prepare it himself by removing the

flesh. He notes asymmetries and unique features, from the brow

to the nasal cavity to the jaw line. Then he consults the

standard skin-thickness charts that other artists and anthropologists

have devised for this work.

But the charts are only a beginning.

There's a rhythm throughout nature,” he said, “a harmony,

whether it be in dance, painting, sculpture, or music, so I try to

work with that. If you take any good musician's composition and

try to change one part, it's going to go sour. So if you take

the facial tissue charts and try to follow them, but then find that

one part of the form doesn't feel right, you make it work with the

harmony, not the charts. That's what's most important.

That's my theory.”

|

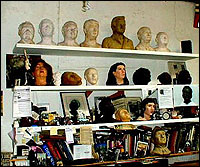

Busts on a wall in the studio

(the author) |

|

|

Generally, the technique involves first making a cast of the skull

(or using the skull itself). Small holes are made for wooden or vinyl

pegs to be inserted for measuring the facial tissue depth. Then

modeling clay fills in the muscles and features around the nose,

mouth, cheeks, and eyes, and a thin layer of plastic or clay goes over

the skull or mold. Facial features are molded to capture the

person's basic look, and a wig and artificial eyes are added, along

with make-up similar to what an embalmer might use for cosmetic

enhancement.

|

| A work in progress

(the author) |

Bender does not wear a watch and works by his own hours, napping

along the way. “I don't think about sculpting. The image

is there. I'm just following the lines that have been

formulating in my head. It just happens. I don't stumble

over the forms. It's like music. It just comes out.”

|

|

Once the sculpture is the way he wants it, he makes a mold out of

rubber and fiberglass plaster, and then polishes it. The final

step is to take a picture for fliers, newspapers, and television.

Sometimes there's something unusual about a skull, and that helps

with identification. Once he was told that a victim would be a

“mouth-breather” based on the shape of her palette, so he planned

to shape her face with her mouth slightly open. Then, at the crime

scene, which was a trash heap, they found a single lens from a pair of

glasses, so he went to look at the frames that would go with the

victim's face. He selected a pair and put them on the sculpture

that he'd done from the skull, and the police were then able to

identify the victim. The glasses helped because they weren't

ordinary frames.

“That's where art supplements science,” Bender said.

Since this work is intense, Bender periodically has to purge it

from his system.

“Pretty much once a week, I stay up all night and dance. My

assistant will come over and we'll listen to music and unwind.

That helps to clear the palette, to just have fun and let loose.

When I'm done with a case, I clean it out. I download the case

into my fine art, into watercolor or sculpture. Then I'm on to the

next one. If you try to be the ultimate crusader, take it

personally, and fight to get every case solved, after a while, you

can't see the forest for the trees. You have to keep some balance.

I have to keep my art clear so that it works. I can tell when I have

to make adjustments.”

Bender said that while this work may appear easy, because he can

make a sculpture fairly quickly, it is hardly as easy as it looks.

“It's a constant effort. It may appear easy to people

because I can do a sculpture in five or ten days. But how many

months prior to that, waiting for that job, did I think about it?

That's where all the time is. The thought process takes hours,

days. When I actually render it, I would hope that my hands are

good enough now that I know the form and I don’t have to think about

how to form a nose. I make the nose from the image that's in my

mind from those three or four months of formulation. Is it

effortless? No. It just appears that way, because people

don't know the thought process that goes on in a creative person's

head."

|

Frank poses with some of his work

(the author) |

Bender emphasizes that his work is not just about what he is

thinking; it is the product of a team. “How many people did I

contact or go see that helped me know what type of clothing someone

wore or what their habits were? I go to different hairdressers

to learn from them so where there's no hair in a case, I can work like

a hairdresser and give the person a hairstyle. I rely on many

people. [One doctor] is an expert on bite marks, so when we have

a bite mark on a body, he can do an impression and figure a lot out.

The detectives supply me with information. I've gone to meet

with doctors to learn about scars and surgery. There have always

been and always will be people that are willing to help solve

crimes.”

|

|

|