Female Mass Murderers: Major Cases and Motives — Going Postal — Crime Library

Just after 9 p.m. on Jan. 30, 2006, Jennifer San Marco passed through a heavily guarded security station in a mail processing plant and distribution center in Goleta, Calif., by driving behind another vehicle to enter the building where she had worked two years earlier. No one realized that she had just killed her former neighbor, Beverly Graham, with a shot to the head in her apartment. They apparently also did not realize that she was armed with a 15-round, 9mm Smith & Wesson pistol and ammunition.

At gunpoint, San Marco took an employee’s badge, according to early news reports. The 44-year-old then shot two people in the parking lot before entering the building to shoot four more before she turned the gun on herself, taking her own life. Five died at the location from their wounds and the sixth person died two days later in the hospital. Since San Marco had left behind no suicide note, her motives remain in question.

San Marco had a history of strange behavior, and it was her mental problems that apparently led to her retirement from the post office in 2003 after six years of employment. At that time, she moved to New Mexico. There, she attempted to start a publication, The Racist Press, in 2004, but did not have a license. Those who attended a meeting with her at the time recalled that she sat mumbling to herself in a way that sounded as if she were two people arguing.

And there were other issues: she would stare at people, and once she showed up at a local service station unclothed. Those who knew her recalled her hostility toward minorities, particularly Asians.

Of her seven victims, three were black, one was Chinese-American, one was Filipino, and one was Hispanic. Only Beverly Graham was white. Neighbors from the development where Graham lived reported that she and San Marco had argued while San Marco was residing there.

Goleta, Caligornia.

By the end of the week, reporters for the Associated Press had learned from notes found in her New Mexico home that San Marco believed she was in danger from a conspiracy among workers at the Goleta processing plant. She also left behind indications that she had a will. A check, made out to cash, was found that had the word “will” written on it. She had legally purchased the gun and ammunition from a pawn shop in New Mexico, and the requisite background check had turned up no problems.

San Marco reportedly also had issues with the Santa Barbara Police Department and a California medical facility, but apparently chose to vent her fear and anger at the processing plant. If she meant to have someone inherit her home and money, that person’s identity remains a mystery.

Criminologists called San Marco’s rampage the worst workplace shooting by a woman in United States history. Indeed, they were right. There are few examples of female mass murderers of any kind, even including those who attempted to become one, but simply failed to take enough lives to meet the criteria. In nearly every instance, whether they killed relatives, friends, or co-workers, they had a history of mental illness. At no time did they exhibit the anger management issues of male mass murderers who simply had a vendetta and sought to harm as many people as they could.

Mass killers are generally profiled as white, middle-aged males who have lost their jobs or have some other anger-related issues or revenge fantasies. Disgruntled postal workers, bankrupt day traders, fired plant employees and the like have typically dominated media headlines. One notable exception to this rule is Charles Whitman, a student who went on a shooting spree in 1966 from the top of a tower at the University of Texas in Austin. Whitman is considered a mass murderer, but had not lost a job and did not share other characteristics common to many male mass killers.

By definition, a mass murderer is a person who kills four or more people in a single incident, either at a sole location or in loosely-related locations. Even if one kills a victim hours before a mass slaughter, the first incident is still considered to be the result of the same precipitating trigger. There’s no psychological cooling off period, as there is with serial killers. Some criminologists include on their lists anyone who has killed at least three, but others consider that a triple homicide. In some instances, killers who claimed the lives of one or two victims actually intended to kill more, signifying their intent was to commit mass murder.

Incidents of mass murder have also been grouped in categories, such as family mass murderers, organically-impaired, workplace, mentally ill, and visionary mass murderers. To that list, criminologists James Alan Fox and Jack Levin add perverted love, copycats, and hate crimes. They acknowledge that these categories, as well as those differentiating spree-killing from mass murder, are sometimes unhelpful, as there is a crossover. Mass murderers are sometimes confused with spree killers, and some serial or spree killers having also committed mass murder. Generally speaking, the psychology of a mass murderer is quite distinct from that of a serial killer, especially a predatory one who is not guided by delusions. Often, mass murderers know they will be caught, are trying to make a public statement or wreak revenge, and generally expect to die in the process.

The one category that has received little mention is the female mass murderer, in part because there have been so few. But is it possible that we’ll see an increase in the number of incidents like the one that occurred in Goleta?

In Flash Point: The American Mass Murderer, a sociology text, author Michael Kelleher mentions a couple of female mass murderers and notes a lack of attention to them. The author, however, does not delve into a psychological analysis of these women.

That may be due, at least in part, to an American myth about “female virtue,” as Patricia Pearson hypothesizes in her book, When She Was Bad: How and Why Women Get Away With Murder. Pearson points out that while people in general tend to view women as non-aggressive, in fact, “women commit the majority of child homicides in the United States, a greater share of physical child abuse, an equal rate of sibling violence and assaults on the elderly, about a quarter of child sexual abuse, an overwhelming share of the killing of newborns, and a fair preponderance of spousal assaults.”

She believes it’s easier to envision men committing violence because of their larger, more muscular builds, and criminologists tend to define violence in primarily masculine ways — hitting someone rather than manipulating the demise of their career, or shooting instead of poisoning a victim. Pearson points out that “the capacity of women to use masculine violence emerges very clearly in those societies that sanction its expression,” and offers numerous examples from the field of anthropology to support this.

In short, the way a culture defines gender and violence has an impact on how well the phenomenon is studied in females. In American society, young females are routinely regarded as “less criminal” than young males, and their crimes less serious. Former FBI special agent Gregg McCrary says he has observed this bias and its effect. “We have an overall sense that females are the nurturers in society and males the combatants,” he said. “We carry that stereotype into our perceptions and fail to see that women are equally capable of aggression.”

Yet as society offers more role models for women who exhibit aggression, we’ve seen a concomitant rise in episodes of female violence. We’ve got new role models like kick-boxing Buffy and Lara Croft. As society evolves in its appreciation for strong females, the FBI’s National Incident-Based Reporting System indicates that one in four juvenile arrests involves a female, and arrest rates since 1987 have risen and even surpassed the rate for males. In the past decade, the population of incarcerated females has tripled. It turns out that aggressive behavior for both genders develops in similar ways, and shifting social influences are affecting these trends.

While the female brain appears better equipped to constrain violent impulses, aggression is not just rooted in the amygdales and frontal lobes. It’s also about the society in which children are raised. Aggression is a good barometer of social values, because those values are expressed all around us, suggesting and reinforcing how to behave. Decades of violence research indicates that biology and environment act together.

Add aggressive images, which prime aggressive thoughts, making them easily accessible in situations that call for action. This endorses physical aggression, and repeated exposure to these images only strengthens the priming effect. One study indicates that children who strongly identify with aggressive television characters are more apt to utilize aggression as the preferred method of solving problems. Violence in the home or problems in school such as bullying attunes them to such characters.

Girls may watch female characters kickbox the world into shape, but they don’t learn from these poised warriors the difference between standing up for themselves and being just plain forceful. Images give people ideas, and that’s apparently behind some of the mass murders we’ve seen among females.

On a Thanksgiving Day afternoon in 1980, a black woman driving a 1974 black Lincoln decided to plow into people on the sidewalk on North Virginia Street in Reno, Nev. The woman stared straight ahead as she accelerated, striking several people without stopping. She drove 100 feet down one sidewalk, then over 300 feet down another, and finally drove two blocks down yet another one. She might well have continued, but a witness drove in front of woman’s car to force her to a halt. She was then arrested. And she was angry that she’d been stopped.

The number of casualties rolled in from the five-block massacre, as people were rushed to area hospitals and bodies were removed from the streets. Several limbs remained on the streets, along with knocked over signs, upset trash containers and items that people had been carrying. Twenty-four people had been seriously injured, and five had been killed at the scene by this reckless driver. Two more would die after being taken from the scene to the hospital. Witnesses likened the scene to a battlefield.

Under interrogation, the driver told authorities that her name was Priscilla Joyce Ford, Ford, 51, was a former school teacher who moved from New York to Reno. She told authorities that some people called her “Jesus Christ.” She also claimed to be Adam, of Adam and Eve, and a prophetess. She said that she was tired of life and had deliberately planned to kill as many people with her car as she could as a way to get attention.

“A Lincoln Continental can do a lot of damage, can’t it?” she reportedly said. Then she stated that a voice had urged her to do the same deed when she’d been in Boston six months earlier, but another voice — that of Joan Kennedy, she said — had stopped her. She asked the officers how many she managed to kill, hoping the number was at least as high as 75. Nevertheless, Ford seemed satisfied when they told her she’d killed five. She also admitted that she’d been drinking that day, and her blood alcohol level confirmed she was intoxicated.

Found incompetent to stand trial and diagnosed with schizophrenia, Ford was sent for drug therapy until her competence could be restored. She went to trial in 1981, pleading not guilty by reason of insanity on the charge of six counts of first-degree murder and twenty counts of attempted murder. The proceedings lasted five months with numerous witnesses attesting to Ford’s mental instability. At one point, she insisted that the car had gone out of control and she could not recall hitting anyone. She offered other explanations in her effort for an acquittal, but the jury was apparently unmoved. They found Ford guilty on all counts, and she was sentenced to death. Ford died in prison in January 2005 of natural causes.

The next largest victim toll on record for a female is a tie between two mothers nearly 150 years apart.

A 911 operator received a call on Sept. 3, 1998 from a woman speaking broken English reporting that she had just slaughtered her children.

The woman who made the call was 24-year-old Khoua, a Minnesota mother who strangled her six children, ages 5 to 11, because she was apparently depressed and overwhelmed.

When the police arrived at the home, they found her with an extension cord loosely tied around her neck in an apparent suicide attempt. They transported her to the hospital, while another team looked around the house and found the murdered children.

Her was no was no stranger to police, who had been to the house 15 times in less than two years in response to domestic violence calls. Her’s estranged husband had said she pulled a gun on him, but social workers had not noted any conditions that posed such danger to the children that they ought to be removed from their mother’s care.

During the course of the investigation, police learned that Her had her first child at age 13 in a Thai refugee camp. She also had a short temper and often neglected her kids. At times, she refused to touch them. In a plea deal, Khoua Her received 50 years in prison on six counts of second-degree murder.

A similar incident occurred more in 19th century England. Mary Ann Brough was the mother of seven children she had with her husband of 20 years, George Brough, a servant in England’s royal household.

In 1854, George announced to Mary Ann that he was leaving her because he suspected she had been cheating on him. He also said he intended to take their children away from her, setting into motion a series of terrible events.

On June 10, the day after Mary Ann was confronted by her husband, a man walking by their home spotted a bloody pillow in the window, according to The Encyclopedia of Mass Murder. Neighbors found Mary Ann inside, still alive, but with her throat slit. Bodies of six of her children lay scattered throughout the house, their throats cut open. Mary Ann survived and was charged with six counts of murder. She confessed, telling investigators that she had used a razor on each child, one at a time. One child had protested and another had struggled, but she killed them all before attempting suicide. Mary Ann Brough was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

It’s usually men who annihilate families to “teach a lesson” or to control the situation, but in this case, a woman chose violent means to respond to a threat.

In the Khoua Her case, a restraining order had been placed against her husband, even though it appears she was accused of more serious threats and assaults. Khoua Her received no assistance, and her anger built up until it was too late for her children.

Another mother who killed her five children had a more difficult time with a Texas jury.

On the morning, of June 20, 2001, Andrea Yates was alone with her five children after her husband, Rusty, left for work. In less than two hours, her mother-in-law was due to arrive at her Houston, Texas, home. She’d already had a dress rehearsal, so to speak, filling the tub before, for no apparent reason, but no one in her family viewed her odd behavior at the time as a red flag.

Yates considered herself a bad mother for having led them astray and having allowed them to be rude to her mother-in-law. It was a sign to her that their souls were in danger of going to hell. If she worked fast, she might prevent that. But at the very least, the state would execute her for the murders she was about to commit, and as she would later explain it, that would remove the devil from the world — the devil who visited her and inhabited her at times. She knew that what she was doing was wrong in the world’s eyes, and that would ensure that she would die, too.

Yates filled up the bathtub and started her grim morning’s work with 3-year-old Paul. She went into the bathroom to fill up the bathtub for her grim morning’s work.

After Paul, who was held underwater until he stopped struggling, came Luke, and John, Mary, and the last one was Noah. When she was done, dripping and exhausted, she placed a call to 911 to tell the emergency operator to send an ambulance and the police. Then she called Rusty to tell him that the children were gone. He arrived home just after the police had ascertained that Andrea had indeed drowned her five children and placed four of them on a double bed, covering them with a sheet. In the bathtub, a young boy was submerged amid feces and vomit that floated on the surface.

The central question in this case was whether or not Andrea Pia Yates, 36, had killed the children while in a state of psychosis, or had knowingly done it to escape a life she hated.

Andrea and Russell (“Rusty”) Yates married in 1993, and after the birth of their first child a year later, she began to have violent visions of someone being stabbed. She and her husband, however, shared fundamental notions about family, so she kept her frightening secrets to herself. Rusty followed the teachings of a fire-and-brimstone preacher named Michael Woroniecki.

In 1999, Andrea sank into a deep depression and tried to kill herself with a drug overdose, so Rusty got her into treatment. When they ran out of insurance coverage, she was discharged.

Later, Rusty found her in the bathroom one day pressing a knife to her throat. He got her hospitalized. On the antipsychotic drug, Haldol, she improved slightly. By this time, she had five children, including a baby. When her father died a few months later, she stopped functioning. Again, she was treated, but taken off Haldol and put back into Rusty’s care. He was warned not to leave her alone.

Andrea Yates was charged with intentionally causing the deaths of three of the children with a deadly weapon — in this case, water. She pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. Despite her claims that Satan was visiting her in her jail cell and that she believed that “666,” a biblical reference to the Antichrist, was carved on her scalp, a judge deemed her competent to stand trial and assist in her own defense.

Her trial became a battleground for mental health experts. Yates’ defense team presented her history of delusional depression, use of anti-psychotic drugs and suicide attempts, and they offered documentation that postpartum mood swings can sometimes evoke psychosis.

But the case hinged only on her mental state at the time of the drownings, and the jury ultimately decided she knew the difference between right and wrong at the time of the killings. They convicted her of first-degree murder and she was sentenced to life in prison.

While incarcerated and on medication, she has come to realize what she has done to her children and attempted to starve herself to death.

On January 6, 2005, an appeals court overturned the conviction and ordered a new trial. While Yates’ attorneys appealed on 19 separate legal grounds, the issue that won the appeal surrounded the testimony of the prosecution’s psychiatrist, Dr. Park Dietz. The three-judge panel of the First Appeals Court in Houston decided that the erroneous statements may have precipitated a miscarriage of justice.

Essentially, it appears that the prosecution had attempted to convince the jury that Andrea had seen an episode of the crime show, Law and Order, in which a woman had drowned her children. That character had supposedly been found not guilty by reason of insanity, and the episode was said to have aired not long before Yates drowned her children. Evidence was offered that Yates was a regular viewer and it was surmised that she may have seen the story and related it to her own situation: Perhaps she was a beleaguered mother seeking a way out.

However, no such episode ever aired. The Court decided that the information might have had an effect on the jury decision-making, so a new trial was ordered. Yates’ attorney, George Parnham, put up the bail money in 2006 to move her to a psychiatric institution to await her trial.

The next woman killed four, and her decision to do so was unique among female mass murderers in that there was no evidence of mental illness.

Four people died in the fire in 1986 that consumed the home of Roland and Betty Kirby in Trail Creek, Ind. The victims were soon identified as the Kirbys and two people who were visiting them, Terry Ward and Eugene Johnson. The fire turned out to have been the result of arson, which turned these deaths into murder, so investigators looked around for motive and someone to arrest. The first step in the process was a victimology: Who among the deceased had an enemy?

It turned out that Eugene Johnson had a wife, Patricia, to whom he had been married for 22 years. Terry Ward was his mistress, and Patricia had confronted him in a bar the night before about being with her. Several people had witnessed the altercation, so it wasn’t difficult to believe that she was a viable suspect.

The police learned about another man, Roger Griffen, who was an associate of Patricia Kirby’s and when they questioned him, he admitted that he had driven her to the Kirby home. Patricia likewise confessed committing the murders by starting a fire. Griffen and Johnson were both charged with four counts of first-degree murder. Griffen tried to plead this down to assisting with a criminal, but the court disallowed it.

It was clear at her trial that Patricia had been angry enough at her husband and his girlfriend that she had wantonly taken the lives of four people. In just over an hour, the jury found her guilty. She received four sentences of forty years, to be served concurrently. Griffen got ten years for being her accomplice.

Another homicide committed by females that involved five victims at once was among the most sensational in U.S. history. They, along with one male, were apparently responding to the leadership of a demented, self-proclaimed prophet.

On July 31, 1969, musician Gary Hinman was found stabbed to death in California. A suspect driving Hinman’s car, Bobby Beausoliel, was picked up and there was blood on his clothes. Beausoliel lived on an old movie ranch with a group of hippies led by a man named Charlie, who claimed to be Christ, but no charges were levied against him.

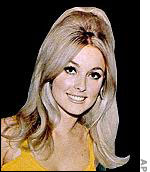

On Aug. 9, at the home of film director Roman Polanski, a massacre occurred that would make headlines around the world. Five people were slaughtered in a blood-drenched spree, including Polanski’s 26-year-old wife, actress Sharon Tate, who was eight months pregnant at the time.

The first victim was Steve Parent, 18, just visiting a resident of the guest house. He had been shot four times in his car as he was leaving the premises. Inside the home were two blood-covered bodies: Sharon Tate, stabbed sixteen times, had a nylon rope tied loosely around her neck. A long end had been tossed over an overhead rafter and then tied around the neck of hair stylist Jay Sebring, Tate’s former beau, also dead. He had been shot once and stabbed seven times. On a door, the word “PIG” was written in blood.

And there were victims who apparently had unsuccessfully tried to flee. Outside on the lawn lay Voytek Frykowski, bleeding profusely from his many wounds. He had been shot five times and stabbed fifty-one times as well as struck thirteen times in the head. Nearby was coffee heiress Abigail Folger, stabbed twenty-eight times.

Shortly thereafter, a married couple, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, were murdered in their home. Pillowcases had been placed over the heads of both victims and a carving fork was immediately visible sticking out of Leno’s abdomen. The killer or killers had crudely carved “War” into his chest and used his blood to write “Death to Pigs,” “Rise,” and “Healter Skelter (sic)” on the walls. Leno was stabbed twelve times with a knife, which had been left in his throat, and he had fourteen puncture wounds from the fork. Rosemary had been stabbed forty-one times.

In October, a young woman named Susan Atkins took credit for her involvement in the massacre. That led the police to her associates on the movie ranch. Eventually they arrested three of the women alleged to have been involved, Susan Atkins, Leslie Van Houten and Patricia Krenwinkel, along with Charles Manson and a drifter called “Tex,” as documented by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi in his book, Helter Skelter.

Manson had urged several of the cult members to go on a killing spree, telling them to make it look like the job of black militants. His vision of “Helter Skelter” (taken from a Beatles’ song off their White Album) meant that blacks would rise up to massacre whites and reclaim the earth. However, the black race would need the help of a white tribal leader to govern things, and Manson was the man for the job.

The jury accepted Bugliosi’s theory about Manson being a mastermind and the girls willing actors. In January 1971, they convicted Manson and two of the women, Atkins and Krenwinkel, of seven counts of first-degree murder. Van Houten was convicted on two counts of first-degree murder. In a separate trial later that year, “Tex” Watson was also convicted for his role.

Bugliosi argued that the three females involved in the murders possessed a syndrome of hostility and rage that preceded their encounter with Manson, and that was unleashed and manipulated by him. Each had an inner flaw that Manson had exploited, focusing their innate ability to be sadistically violent on a common enemy. His philosophy justified their actions and their own inner demons ensured that they would revel in it. They certainly acted at the trial as if they had thoroughly enjoyed it.

Several women have attempted to become mass murderers, but their victim tolls failed to place them officially in that category. Nevertheless, their intent was clear: They certainly had hoped to carry out a plan in the manner of a mass murderer. Had all of their victims died from wounds these women had inflicted, they would have become known as American mass murderers.

We’ll start with Brenda Spencer, a 17-year-old girl, who reportedly was bored the morning of Jan. 29, 1979. In his book Kids Who Kill, author Charles Ewing describes how she came close to taking 11 lives when she shot her new semi-automatic .22 rifle into a school yard. Her father had given her the rifle for Christmas, never dreaming that she might use it to bring harm to so many. Alone that morning, she looked out the window of her San Diego home, saw kids on the playground of Cleveland Elementary School across the street, and decided to start shooting. The school’s janitor took a deadly hit, as did the principal, both of them using their own bodies to shield the children when they realized what was happening.

A police officer tried to help as well, and he was wounded during the 20 minute shooting spree, as were eight of the children. Other officers responded to the emergency, surrounding the building where Spencer lived. Soon the media arrived as well. Spencer kept them all at bay for six hours (other sources say two), talking with negotiators on the phone, before they were finally able to arrest her and stop the shooting. At the time, she reportedly told them that she’d started shooting for the fun of it, because she didn’t like Mondays. “Mondays always get me down.” She had done it to cheer herself up.

Spencer went through at least two psychiatric examinations and the doctors learned that this petite young girl, with a history of problem behavior and substance abuse, had long been obsessed with violent films and images of shooting police officers. At first Spencer pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, but she changed her plea to guilty. Her trial took place in Santa Ana, California, where she was convicted. For each of the murders, she received two terms of twenty-five years to life, and for one count of assault with a deadly weapon, she got forty-eight years, to be served concurrent with the other sentences.

A few years later, another woman with an even more deadly weapon also aimed it against strangers.

On Oct. 30, 1985, as reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer, mid-afternoon shoppers at the Springfield Mall outside Philadelphia, Penn., were startled by gunfire. Outside in the parking lot, a woman shot at several people and then entered the mall, dressed in green military fatigues and a knit cap, and carrying a semiautomatic rifle. Most of the people who spotted her believed she was part of some Halloween prank, but they were wrong. Some of them dead wrong.

Near a restaurant’s entrance, a 2-year-old child, lay on the ground dying and two children were wounded. Outside, a number of people had run for cover. The medium-sized woman aimed directly at shoppers who failed to move fast enough and shot randomly inside several stores. One person, a 67-year-old man, was hit three times.

No one stopped the woman as she made her way, muttering to herself, through the pedestrian area. Several people fell to the floor, some of them bleeding badly. A woman yelled, “Help my husband, help my husband!” At that moment, John Laufer, a graduate student, grabbed the shooter.

“I’m a woman,” she said, “and I have family problems, and I have seizures.”

Laufer sat her down in a shoe store and told her to remain there. He then returned with a security guard, who placed the shooter under arrest. Laufer later said he thought the woman had been firing blanks as a prank. Just before he had stopped her, she had raised the rifle directly at him.

The toll that day was two dead and eight wounded. One of the wounded, a 69-year-old man, would later die, bringing the total deaths from this rampage to three. Those who worked at the mall knew the woman to be Sylvia Seegrist, who frequented the place, often harassing customers. By the next day, it was learned that Seegrist had been trying to get a prescription filled at the mall drugstore earlier for tranquilizers, but the pharmacist had refused to do it because she did not have her Welfare card.

At her arraignment, Seegrist indicated that she had expected to die. Asked her phone number, she rattled off a long string of random numbers. She also lashed out with the statement that she wished she had never been born, and told the court that the reason for her rampage was trouble with her parents. Finally she said, “Do you have a black box? That is my testimony.”

There was no doubt that Sylvia Seegrist had a long record of mental illness. She had been diagnosed at the age of 15 with a mental disorder so serious that she faced a lifetime of drugs or hospitalization. Since her illness involved a developing hostility and aggression, she quickly alienated family and friends. That left her lonely as well as disoriented, with no one to help her find her bearings. She was hospitalized a dozen times and then given drugs. No professional followed her case, although she saw several different psychiatrists for the medication.

Since she often did not take the drugs appropriately or they did not work well, her delusions and anger worsened. In the weeks prior to the shooting, people who knew her said that she had been acting “terribly psychotic.” Her mother, Ruth Seegrist, told reporters that Sylvia was “completely out of touch with reality.” She had urged her daughter to commit herself earlier that week, but Seegrist had responded that she’d rather go to prison.

Seegrist was found guilty but mentally ill and given three consecutive life sentences, with a minimum of 10 years each. Sent to a psychiatric facility for evaluation, she was eventually moved to the state correctional institution at Muncy.

Only two-and-a-half years later, another woman meticulously planned a mass murder-suicide that still defies comprehension.

On May 20, 1988, Laurie Wasserman Dann set out to kill an unknown number of people in Illinois. Although she fell far short of her goals, had she achieved them, she would have had the highest victim toll of any female mass murderer to date. But this was not the first indication that she was capable of violence. What investigators learned after her rampage, as reported by Lane and Gregg, was that she had married in 1982, but the marriage had lasted only four years. At some point during the divorce proceedings, someone had entered the home of her estranged husband and stabbed him with an ice pick. He could not identify his assailant, but reportedly he believed it was his wife. Other people, too, had apparently been the recipients of her violent retaliations. She damaged property and engaged in shoplifting as well, and was so erratic that she finally lost her job.

As shocking as it is to learn, Dann was nevertheless able to purchase handguns. Once she had them, her plots of vengeance took on a more sinister quality. During her deadly advance, she first drove to several homes where she had worked to deliver food laced with arsenic. She left her packages on the front porches and continued with her fatal errands. The next two stops were to start fires before she drove to Hubbard Woods Elementary School in Winnetka, Ill. Armed with a .357 Magnum, she entered the school, shot and missed a boy, and then went into a classroom. She started shooting, hitting six of the kids and killing her sole victim, an 8-year-old boy. No one tried to stop her as she left, got into her car, and drove to yet another location.

Then she left her car and knocked on the door of a house where she was clearly a stranger. They said later that Dann had offered a story that she had been raped and had shot her rapist. They could see she was unstable, and one member of the family attempted to apprehend her as she forced her way inside. She shot and wounded him, then went to a room on the second floor. Locking herself in, she waited.

The homeowners called the police, and they brought Dann’s father to the scene to plead with her. She did not respond. Finally, the police went in to corner and confront her, but they were too late: with her .32 revolver, she had shot herself through the mouth. Like many male mass murderers, she had been angry, had sought revenge against imagined slights, and had holed herself up to end her own life.

Dann left no explanation for her actions, but her acquaintances indicated that she had a long history of anger management issues, yet had never been hospitalized or diagnosed.

Whatever drives these women, be it inner demons, a demand for attention, or retaliation, a greater percentage have been mentally ill than their male counterparts. Even so, as social tensions increase, we may yet see more aggression from women in the form of mass murder.

Bugliosi, Vincent and Curt Gentry. Helter Skelter. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1974.

Easton, Pam. “Andrea Yates Leaves Hospital for Jail,” Associated press, February 2, 2006.

Eshleman, Russell, Mark Butler, and David Lee Preston. “Woman Opens Fire on

Shoppers at Springfield Mall.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 31, 1985.

Ewing, Charles Patrick. Kids Who Kill. New York: Avon, 1990.

Flock, Jeff. “Chilling Details of the Houston Child Killings.” CNN.Com. June 22, 2001.

Fox, James Alan and Jack Levin. Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder. Sage, 2005.

Kelleher, Michael D. Flash Point: The American Mass Murder. Westport Connecticut:

Praeger, 1997.

Lane, Brian, and Wilfred Gregg. The Encyclopedia of Mass Murder New York: Carroll & Graf, 2004.

Lassiter, D. Killer Kids. New York: Pinnacle, 1998.

Lavilla, Stacy. “Why Her?” Asian Week, Sept. 17-23, 1998.

Linedecker, Clifford. Babyface Killers. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999.

Pearson, Patricia. When She was Bad: How and Why Women Get Away with Murder. New York: Penguin, 1997.

“Police Place Mother in Custody for Killing Six Children,” The Holland Sentinel Archives. Sept. 5, 1998.

Ramsland, Katherine. Inside the Minds of Mass Murderers: Why They Kill. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2005.

Roche, Timothy. “Andrea Yates: More to the Story.” Time, March 16, 2002.

Spenser, Suzy. Breaking Point. New York: St. Martin’s Press. 2002.

“Strange Behavior: 8 are now Dead,” Singapore News, Feb. 2, 2006.

Transcript of Andrea Yates’ Confession. The Houston Chronicle, Feb. 21, 2002.

“Doctor: Yates Suffered Mental Illness,” Court TV .com, March 8, 2002.