All about Robert Ressler by Katherine Ramsland — An Abundance of Victims — Crime Library

In Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, during the month of November 2001, eight women were found murdered and dumped in cotton fields. These killings appeared to be part of a decade-long wave of kidnappings and murders that had reportedly claimed nearly 200 victims. Since 1993, 50 bodies have turned up and dozens of men have been interrogated in this border town across from El Paso, Texas, but the murders continued. Many victims were young women who worked in assembly plants that supply the U.S.

portrait

(Louis Myrie/LMI)

In 1998, a women’s group from Mexico City had brought media attention to the fact that nothing was being done about these murders. Authorities contacted Robert Ressler, criminologist and former FBI profiler, to get help narrowing down suspects in their investigation and to train their task force in the psychology of serial killers. Ressler went over all the documentation and concluded that not all of the murders were linked by similarities.

“They were talking in excess of 100 women at the time,” he recalls, “and saying that someone was running amuck and had killed them all. When we sorted all the cases out, we ended up with 76 homicides of concern. I did a preliminary VICAP assessment and determined that a number were connected and a number were not. Some suspects were clearly family members and some were gang members. They had one guy in custody, an Egyptian national named Sharif Sharif who had a horrendous record in the United States for rape and assault, and when he was run out of the country, he started up again in Mexico. He was charged with a dozen homicides [but convicted in only one]. I also believed that some of the murders were done by peoplepossibly a teamcoming over the border from El Paso. So we also met with the El Paso police to get their cooperation.”

Ressler set up a surveillance of the buses that let young female workers off at night. “I went behind the buses with cops and saw that they were dropping these women in dark locations. Anyone interested in abducting them just had to follow the buses. Some of the bus drivers knew the routes and they could easily come back later when they weren’t driving to get these girls.”

The following year, five bus drivers were arrested for thirteen of the murders and disappearances, and became suspects in five others.

In the most recent spate of killings, it was bus drivers once again. A witness identified a man he had seen dumping a body in the same field where seven others were then found. That led to the arrest of two bus drivers, Victor Uribe and Gustavo Gonzalez, who both confessed to kidnap, rape, and murder. One even said that he had killed three more, although those bodies were not located. Together these two men would get intoxicated and when they spotted a vulnerable woman, would force her into their van to rape and kill her.

While crime shows on television generally indicate clear patterns in serial homicide, criminal profiling can be complicated by many factors and only those with experience can come into a crime scene of such magnitude and provide helpful assistance.

Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal

Lector from The Silence of the

Lambs(Robert Ressler)

Most people first heard about the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit (BSU) from the movie or book by Thomas Harris, Silence of the Lambs. Unit director Jack Crawford was influenced to some extent by talks that Harris had with Supervisory Special Agent Ressler, who had learned the psychological principles involved in profiling from pioneers Howard Teten and Pat Mullany.

“They were the original team that dealt with profiling and crime scene assessments,” Ressler explains. “They started organizing people for this program in 1969, and when the FBI Academy opened in 1972, that’s when the unit really got established. I joined them in 1974.”

This was four years after he had come into the FBI. After he’d served eight years in the army, from 1962-1970, he went to graduate school at Michigan State University. Ressler was then recruited by an agent in the Lansing office who ended up becoming the assistant director at Quantico. “When they opened the Academy, they had different departments, like a university, and I was recruited into the Behavioral Science Unit, which dealt largely with instructing those people who came to the Academy as students.”

He remained with the BSU for 16 of his 20 years at the FBI, retiring in August of 1990. By that time he had introduced several programs that contributed to the development of the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime. Then in 1985 he became the first Program Manager for VICAP (the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program). The concept for VICAP was to collect information about solved and unsolved homicides, specifically those that were serial, random and/or involved abduction. The database also included information about missing persons where foul play was strongly suspected and unidentified dead bodies in which the manner of death appeared to be homicide. Local and international law enforcement agencies could connect to the growing database and either provide further information or utilize the information stored there to help solve their own crimes.

Even after Ressler retired, he has continued to offer workshops in criminology, to serve as an expert witness, and to introduce the VICAP system into other countries, including Japan, South Africa, and Poland.

The behavioral profilers who went on the road to offer instruction to local law enforcement agencies decided to go into maximum-security prisons to interview some of America’s most notorious murderers.

“In 1974, there was no operations unit yet,” Ressler says. “We were just teaching. Around 1978 I came up with the idea of improving our instructional capabilities by conducting in-depth research into violent criminal personalities. I suggested we go into the prisons and interview violent offenders to get a better handle on them and to formulate a foundation for criminal profiling. If I were in California, for example, I would contact the agent who was our training coordinator there and have him set up interviews at local prisons with people like Charles Manson or Sirhan Sirhan. At the conclusion of our training, I would do the interviews.”

The initial program involved 36 convicted offenders, but over the years Ressler participated in over one hundred such interviews. In the process, he coined the term, “serial killer.”

“It wasn’t from a specific case,” he points out. “It just became evident that I was dealing with a lot of cases that were repetitive homicides. The media was calling all of them ‘mass murder’ without any differentiation, and my colleagues and I became aware of the fact that this was too general. We thought we ought to come up with a way to identify different forms of homicidal behaviors, so we started coming up with terms. ‘Serial’ became more or less self-evident because I’d been to England and there they called repetitive crimes ‘crimes in a series’ or ‘series crimes.’ I didn’t want to just lift the British term, but I was thinking along those lines. When I was a kid, I’d go to the movies and we’d watch these ten-minute serial adventures that they used before the main feature and it took several weeks to play out the story. So from that I started calling these crimes ‘serial crimes.'”

The goal of the interviewers was to gather details for a database about

- How murders were planned

- How murders were committed

- What the killers did afterward with the body

- What they did and thought about once they left the crime scene or dumpsite

From compiling information from the many cases, the interviewers learned:

- Patterns of an offender’s values

- The development of sexual-homicidal fantasies

- Patterns of an offender’s thinking processes

- Levels of recall of the crime

- Degree of an offender’s sense of responsibility

- The evolving of MO from experience

- The nature of ritual at the crime scene

To make the interviews as detailed as possible, the agents researched as much as they could find out about a particular killer. That way they could establish a “focused interest” in the target subject. Focus conveys respect, which generally helps to establish rapport and get results. It was important, they knew, to understand the subject’s world and to go into it without judgment about the crimes committed. The point was to get information and all project participants were to keep that as their primary goal.

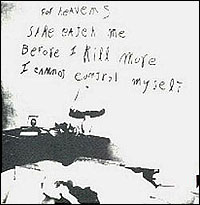

Among those killers who made the list, Ressler included one that had influenced him in childhood, William Heirens. In December 1945 at the age of 16, Heirens broke into an apartment on Chicago’s North Side to steal something. Confronted by Frances Brown, 33, he shot and killed her. Then he found a knife and stabbed her. He tried to wash her off and then wrote on the mirror in lipstick, “For Heaven’s sake catch me before I kill more. I cannot control myself.” The following month, he killed and dismembered a six-year-old girl and distributed her parts into sewer drains. The police tried to track him down but failed until June 1946, when Heirens entered an apartment and was chased and grabbed by the police. He confessed, added another killing that had not been linked to him, and was convicted of the three murders.

“Even as a kid, I had been interested in law enforcement,” Ressler recounts. “I’d play cops and robbers, and since my father worked for the Chicago Tribune, he would bring home the newspaper. I learned that there was a killer loose in Chicago who was killing woman and leaving writings on the wall, so I started following it. Before he was identified, I conjured up a game with other kids to form a detective agency. We had cap guns and cameras, and we’d follow neighbors around and conduct crime scene examinations to find ‘the Lipstick killer.’ We got old tubes of lipstick from our mothers and wrote things on walls. We did this every day and at the end of the day we’d meet together to compare notes. Then when the thing concluded with Heirens’ arrest, we all congratulated ourselves on our part in the investigation that caught the killer.”

When Ressler was scheduled to give instruction in southern Illinois, he recalled that Heirens was in Vienna Men’s Correctional Facility not far from there, so he got permission to interview him. “It was weird,” he recalls, “because many kids have sports heroes and that sort of thing, and I wanted to meet this serial killer. I told him that I’d followed his case. He was about nine years older than me and he was kind of taken aback that, in a sense, he had a fan.”

Aside from this interview, Ressler was involved in many others and on the list were murderers like Charles Manson, Sirhan Sirhan, Richard Speck, Edward Kemper, and John Wayne Gacy. In fact, Ressler conducted one of the last interviews with Gacy before the man was executed.

Gacy (CBI)

Gacy, a businessman and charity worker in Des Plaines, Illinois, became a suspect in the case of a missing boy in 1973. Within a month, investigators had found the remains of 28 young men buried in the dirt crawl space beneath his house. He admitted to dumping five more into a nearby river. When tried for these murders, he used an insanity defense and one of the psychologists who examined him claimed that he’d experienced thirty-three separate cases of dissociated compulsion, otherwise known as “irresistible impulse.” The jury didn’t buy it and Gacy was convicted and sentenced to die. As appeals delayed his execution, he made himself available to some interviews. Ressler, who had already spoken with him a number of times, went in again.

“We had lived on the same street,” he says. “It was eerie to be with him. I got into the investigation on that one with the police after they had already developed him as a suspect. They suspected him of one missing kid and then started finding the bodies, so I helped them sort out what they actually had from the standpoint of a multiple homicide. They had never encountered something like it before. I also helped them prepare the prosecution of the case.”

About being face to face with someone like this, Ressler remembers Gacy as quite manipulative. “Yet he was gregarious and outgoing enough in the many interviews I had with him that even in his attempts to manipulate, he revealed a great deal of his personality and his patterns and motives. He’d get angry and then friendly. In a single session we’d go through a gamut of emotions. A lot of it was play-acting on his part, but we seemed to get along real well. There was no misperception, however. I was there to dig him in deeper. I believed that he was responsible for more than 33 homicides. He had traveled to 14 states during the time that all this went on, so I was trying to get more information and he was trying to maintain his status quo as a victim. These guys were victimizing him, he said, and he had a number of stories about them, but if you put all the stories together, it didn’t make any sense.”

Gacy was among many manipulative killers that Ressler encountered, but in some cases, he’s called on a special type of expertise that few other profilers have.

Before joining the FBI, Ressler had also served as an agent supervisor for the U.S. Army’s Criminal Investigation Division (CID), and this experience was useful for examining killers who claimed they were victims of post-traumatic stress from Vietnam.

In the case of Arthur Shawcross, who had murdered at least 11 women in less than two years, Ressler’s expertise was particularly astute. Shawcross had murdered and mutilated two children when he was 28, gone to prison for 15 years, had been paroled, and then began to kill prostitutes in Rochester, New York. He was caught in January of 1990 with the help of an FBI profile that indicated he’d return to the bodies to indulge in postmortem mutilation. As the New York State Police took to the air to search for the bodies of several recently missing women, they spotted one on the ice on Salmon Creek off Highway 31. On the bridge overhead was an overweight, middle-aged man getting into a car. When they caught him, they had their manArthur Shawcross.

While he confessed in detail and even showed the police the location of two more bodies, his defense lawyer brought in psychiatric experts to claim that he suffered from brain lesions that caused dissociative states and from post-traumatic stress disorder from both childhood abuse and experiences in Vietnam. Shawcross claimed that he became adept at modifying weapons while in Vietnam and went off on his own for days into the jungle, because after he saw American soldiers being killed, he had an emotional breakdown that turned him into a killer. He couldn’t feel any longer and he became a predator. He claimed that he killed children and then took on the role of terrorist. He killed for the thrill of it, spurred on by episodes of extreme violence that he’d witnessed.

“In that case,” Ressler says, “the prosecutor, Charles Siragusa, had brought on board forensic psychiatrist Dr. Park Elliot Dietz. I had recruited him into the BSU as a consultant, so because Siragusa was not conversant with military terminology and records, Dietz recommended that I be brought in. I looked over the military records and compared them with interviews that Dietz had done, and the information that was brought out indicated the Shawcross was malingering quite a bit. It was clear that he was being deceptive and that opened up the door to breaking down his story of how his homicidal tendencies came about. Allegedly he was under hypnosis with the defense psychiatrist Dorothy Lewis and we saw these tapes she had and realized the interviews were bogus. He was just leading her by the nose.”

In the end, the jury was unconvinced that Shawcross had failed to appreciate what he was doing when he killed the women and he was convicted of 10 murders. He pleaded guilty to one more and received life in prison.

In 1990, Ressler retired from the FBI to continue his career in criminology in another manner. He now directs Forensic Behavioral Services International, and he contributed to and co-authored several books, including Sexual Homicide: Patterns and Motives (1988), The Crime Classification Manual (1992), Whoever Fights Monsters (1992), Justice is Served (1994), and I have Lived in the Monster (1997). His specialties for consultation include:

- Criminal personality profiling

- Sexual assaults

- Threat assessment

- Crime scene analysis

- Hostage negotiation}

He also continues to learn about killers. Although colleagues criticized him for it, soon after he retired, Ressler agreed to serve as a defense expert for the attorney representing serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer. He believedand he was rightthat there was much to learn from getting that close to this infamous cannibal-killer so soon after his incarceration.

(Robert Ressler)

Jeffrey Dahmer was an enigma. Living in an apartment in Milwaukee, he burst quite dramatically into public consciousness in July 1991 after a man named Tracy Edwards ran down the street with handcuffs on and told police that someone had tried to murder him. He led them back to apartment #213 and what unfolded afterward was an investigator’s nightmare. The smell that hit the officers that evening indicated decomposition and a look inside revealed human heads, intestines, hearts, and kidneys stored in the freezer. But that wasn’t all. Bones and rotting body parts lay around the place, along with complete skeletons. Snapshots showed mutilated bodies, and the discovery of chloroform, electric saws, a barrel of acid, and formaldehyde told the rest of the story. In all, investigators were able to find the remains of 11 different men. It took Dahmer’s confession to add six more, and his first occurred when he was only 18 years old.

He was living alone in his family home when he felt the need for company. He found a hitchhiker named Steve Hicks and brought him back to the house. They got high together and when Hicks decided to leave, Dahmer smashed a barbell against the back of Hicks’ head and then strangled him. “I didn’t know how else to keep him there,” he told Ressler during their nine-hour interview. He quickly discovered that he was aroused by the captivity of another human being, and then when he cut the body into pieces for disposal, he was excited all over again.

When he moved in with his grandmother, he planned to dig up the body of a young man who had recently died, but thwarted in that, he began again to pick up men to bring back. There he’d drug and strangle them, and then have sex with the corpse. After that, he dismembered them. One man he believed he’d beaten to death while intoxicated.

Then he got his own apartment and followed his compulsions with more regularity. In an effort to create “zombie-like” slaves, compliant and without intellect, he tried drilling holes into the heads of his unconscious victims and injecting acid or boiling water into their skulls. (One man actually walked mindlessly out the door but was soon retrieved.) He also tried to cut off the faces of his victims and keep masks, but was unable to preserve them correctly. While he was careless at times, so were the police, so he managed to get away with murder again and again until he was finally stopped.

When defense attorney Gerry Boyle asked for an expert opinion, Ressler made it clear that while he was free to work for either side on a given case, he would not take one on that made him uncomfortable. “The agreement I had with Gerry Boyle was that he was not trying to get Dahmer off the hook and released back into free society. The best that would happen was that Dahmer would spend the rest of his life in a mental institution. In fact, if he were cured there, Boyle was holding back some of the homicides where Dahmer could be considered sane, so that if he were freed, he would have to go back to court and be prosecuted for those other cases. It was a foolproof defense that served Dahmer’s interests as a mentally ill person and at the same time served society’s interests. So I went along with it because toward the end of his murders, I believed he was mentally ill, where he was not in the beginning. Over the course of his 17 homicides, he showed some decompensation of his mental state. He was organized at the beginning and became disorganized at the end. With that in mind, my task was to interview him at length and give Boyle a report. It was worth it for me just to learn more about this type of behavior.”

Even as Ressler broadened his expertise domestically, he was also called into cases abroad, and one he remembers well involved a serial killer whose violence exceeded many of the more notorious murderers in the US.

Between July and October 1994, 15 bodies of females who were in their twenties were found in South Africa, near the Pretoria-Johannesburg suburb of Cleveland. All had been raped and strangled, all were openly displayed, and the killer had removed personal items from the scene. Most of the victims were commuters, unemployed, or students. A man was identified as the offender, but when 15 more bodies turned up the next year in another remote suburb, Atteridgeville, it was clear that the real killer was still at large. Seven months later, another cache of bodies was discovered near Boksburg with the same MO but dumped closer together, and these three groups of victims came to be dubbed the ABC killings after the areas in which they’d been found.

“They had over forty homicides that they believed were connected,” Ressler reports. “There was a psychologist named Micki Pistorius who was working as a volunteer with the South African police service. Since they had no expertise on multiple violent homicides, she got them interested in bringing me over. Ever since apartheid had shut down, there had been a certain lack of control by the police because they were pulling back on their oppressive posture, and after years of oppression, some people go a little overboard. Their murder rate had exceeded the United States, and we have one of the highest in the world. So they brought me over to work on what would turn out to be a series of 43 documented killings by one person. We laid out some of the basics and he was caught, so that was a success.”

One thing Ressler and the newly-trained task force did was return to the crime scenes to see what they could determine about the killer’s behavior and it became clear that he (or they) had returned to the bodies. There was also evidence from one site to the next of escalation and developing expertise. Ressler deduced that the offender was familiar with the areas, had done prior surveillance, and had grown arrogant. He was also probably luring victims rather than attacking them by surprise.

The resulting profile was detailed, but included the fact that the offender was black, owned a vehicle, appeared to be well off, but was young and had a strong sex drive. Ressler believed he would soon begin contacting the police or newspapers, which in fact, he did. An anonymous caller claimed that he was doing these murders because he’d once been falsely accused of rape and prison had ruined him. When police finally caught him he turned out to be Moses Sithole, a 31-year-old youth counselor.

While Ressler consults on cases like this, he also works hard to bridge the gap between psychiatry and law enforcement, and toward this end he brought two associates into his company. He calls them the “new generation” of profilers, and it’s clear that they do bring a different perspective.

(Robert Ressler)

Currently Ressler is a criminologist in private practice for consultation and expert witness services. He has two associates, Dr. Thomas Muller, Chief of the Criminal Psychology Service within the Austrian Federal Ministry of the Interior, and Dr. Christie Kokonos, a forensic psychologist.

Dr. Muller was trained in the Federal Police School in Innsbruck, Austria, and became a member of the SWAT team. He then acquired graduate degrees in psychology. Now among the areas in which he teaches are hostage negotiation, abnormal criminal psychology, criminal profiling, and threat assessment, and he established the Criminal Psychology Service in Austria, which he heads. He has also worked together with Ressler to train other investigators abroad, notably in Poland, Germany, South Africa, and the U.K.

(Robert Ressler)

Dr. Kokonos has consulted with state and local police departments in Pennsylvania on child abduction, homicide, rape, suicide, and autoerotic fatalities. She seeks to promote an interdisciplinary approach to forensic science through the integration of investigative techniques and psychological research. In Camden, New Jersey, she works at the Riverfront State prison on psychological and parole evaluations, and does risk assessments on sexually violent predators.

The original FBI project to study violent offenders had the goal of understanding the fantasy structure that motivates the serial and sexual killer. Ressler and his associates continue to examine this phenomenon with the infusion of insights from psychology with the hope of developing a more standardized body of knowledge. For years, Ressler lectured to psychological groups to explain the FBI’s system and to encourage professionals to work with it. For that, he received several prestigious awards and was granted an assistant professorship in psychiatry at Georgetown University.

“The original profilers pretty much emanated from the behavioral science work at Quantico,” he explains, “and it spread from law enforcement to the academic. By bringing in Dr. Park Dietz and others like him, we started spilling it over into the professional community, and where psychiatry had initially been at odds with the FBI approach, a lot of mental health professionals then got on board. Over the years, the forensic community has pretty much accepted what we were doing in behavioral science and absorbed it.”

This, he believes, is important, because it used to be the case that forensic work was simply a sideline that some clinicians might take on, but often they had little experience with criminals and crime scenes. “If you go back to the early criminal cases where they brought in psychiatrists,” he says, “you’ll see that they were working out of theories rather than from experience. The difference now is that professionals are fulltime forensic psychiatrists, so they devote their entire career to the forensic aspects of their trade. They get into crime scene information, interviews with offenders, and testifying in court on a regular basis. They’re now more experienced.”

Dr. Kokonos is enthusiastic about this direction. “I’m different as a profiler because I’m not law enforcement, and traditionally that’s what profilers have been. I’m mental health, and we’ve typically not had access to law enforcement and what they do. Most psychologists have never seen a crime scene or crime scene photos; they have no idea what it takes to do an investigation; have no training; and are completely unaware of how an investigation goes. To do this kind of work, they need to be able to look at a picture of a victim and understand the injuries they see from having been exposed to a lot of cases. Most mental health people fail to understand sex offenders and the role of fantasy in their motives and behavior. So I’m helping to pull law enforcement and mental health together. I help to educate law enforcement about what they need to put into their reports that a psychologist may need down the road, for instance, in order to help keep a serial rapist in prison. The officers need to understand how important it is to do a very thorough victim interview, to put things down in the right order, and to know how the various mental disorders correspond to specific acts of violence. They also need to know that there are different types of rapists. Understanding what to look for is important. In fact, both sides need training so that they can determine whether offenders are likely to re-offend, what kind of victim they might choose, and whether they will start to branch out. Psychology and law enforcement need to work together. The time is right to do that.”

As she moves more deeply into this arena, Kokonos relies on Ressler in a supervisory capacity. In one incident, as a test, they did their profiles separately and then compared them.

“We worked on a sexual assault and murder case in northern Pennsylvania,” Kokonos recalls. “A little girl, age 11, was grabbed after she left a Halloween party. She walked home with another girl, but a few blocks from her house they parted ways. A witness actually saw her coming down the street and then saw a man come out from a side street. He grabbed the girl, threw her in a car, and was gone before anyone could get there. This was on a Wednesday. On Thursday they found an article of her clothing and then on Friday morning they found her. We believed that she had not been killed until Thursday night, so the man who grabbed her had kept her alive for a period of time. This is unusual and I thought it was likely he might do it again and that he’d done something sexually deviant in the past.

“I went through all the information from the crime scene and wrote up my profile. I sent Mr. Ressler the photos and reports, and then sent him my profile in a sealed envelope. I had the state police meet us at his house and when we got there, he gave the police his version of what he thought the offender would be like and then he opened mine. He read it and said, ‘Did you read my mind?'”

For Kokonos, this was a gratifying moment, in part because the better she gets at it, the more she can help to advance the vision. Many people now trained in law enforcement learn some psychology and many psychologists interested in the forensic field are getting better at understanding crime and crime scenes. As Kokonos says, the time is right for a merging of the two disciplines for improved techniques in profiling.

Whoever Fights Monsters – My Twenty Years Tracking Serial Killers for the FBI

is an informative and insightful account of Ressler’s 30-year FBI career and the development of the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program. Ressler’s numerous interviews with convicted killers (e.g., David Berkowitz, Ted Bundy), use of behavioral sciences principles, and many years of detective experience have given him an uncanny ability to “read” a crime scene and develop a criminal profile of the offender. His involvement in multiple serial killer investigations gives the reader an insider’s view into police work.

I Have Lived In the Monster

Delving deeper than ever before into the criminal mind, Ressler recounts his years since leaving the FBI, working as an independent criminal profiler on some of the most famous serial murder cases of our day.

Ingeniously piecing together clues from crime scenes, along with killing patterns and methods, Ressler explains his role in assisting the investigations of such perplexing international cases as England’s Wimbledon Common killing, the ABC Murders in South Africa, and the deadly gassing of Japan’s subway. We’re also witness to Ressler’s fascinating, in-depth interviews with John Wayne Gacy, the first and last one America’s most prolific serial killer would ever grant, plus a shockingly candid discussion with “cannibal killer” Jeffrey Dahmer.

Daring to understand the depraved minds of serial killers, Robert K. Ressler returns from the deepest abyss with an unforgettable account that is as riveting as it is shocking.

Justice is Served

This is the true story of Ressler’s determined efforts to prove Cleveland judge Robert Steele guilty of arranging the murder of his wife Marlene in 1969. A young FBI agent, Ressler’s investigation led him into the lives of politicians, prostitutes, pimps, gamblers, and murders in a world of greed, sex-for-pay and multiple betrayals. Martin’s Press.

Sexual Homicide — Patterns and Motives

This authoritative book represents the data, findings, and implications of a long-term F.B.I.-sponsored study of serial sex killers. Specially trained F.B.I. agents examined thirty-six convicted, incarcerated sexual murderers to build a valuable new bank of information which reveals the world of the serial sexual killer in both quantitative and qualitative detail. Data was obtained from official psychiatric and criminal records, court transcripts, and prison reports, as well as from extensive interviews with the offenders themselves.

Crime Classification Manual

This landmark book classifies the three major feloniesmurder, arson, and sexual assaultbased upon the motivation of the offender, standardizing in one place, for the first time, the language and terminology used throughout the criminal justice system. A decade in development, this work forms the basis of contemporary investigative “profiling,” the highly acclaimed strategy enabling law enforcement personnel to solve a crime by generating a “profile” of the suspect. This will provide police officers and other law enforcement personnel, as well as mental health professionals, in any size community, access to the same information as used by the FBI to coordinate their investigations

ROBERT K. RESSLER: TAKING ON THE MONSTERS

Bibliography

Interviews with Col. Robert K. Ressler and Dr. Christie Kokonos.

Ressler, Robert K., Ann W. Burgess, and John E. Douglas. Sexual Homicide: Patterns and Motives. New York: The Free Press, 1988.

Ressler, Robert K. & Tom Schactman. Whoever Fights Monsters. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Ressler, Robert K. & Tom Shachtman. I have Lived in the Monster. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

“Mexico Arrests Two Men in Murders of Eight Women,” Reuters, November 12, 2001.