A Profile of Tim Miller and Texas EquuSearch — A Missing Girl — Crime Library

Teketria “Teeky” Buggs was only 12 years old. On December 2, 2005, she was asleep on the couch in her home, as her family recalled, in the tiny Texas town of Orchard, in Fort Bend County. Later that same day, she disappeared. Her stepfather, Steven Carrington, apparently had seen her that evening, but he woke her younger sister at about 2:00 a.m. to ask where Teeky was. No one knew. The family reported her missing on Saturday morning, and when it was determined that none of her personal belongings was missing, an Amber Alert was issued.

By Sunday night, according to the news site Fortbendnow.com, a mounted search-and-rescue team from Dickenson, known as Texas EquuSearch, was helping sheriff’s deputies search abandoned buildings and a 12-acre field surrounding the girl’s home. Her mother, Laronald Foy, believed Teeky had left the house Friday evening with someone she knew. The police had their suspicions, since it was not the first such disappearance from the extended family at this residence, but they did not yet voice them. For the moment, they assumed Teeky was alive and could be found.

Texas EquuSearch founder Tim Miller acknowledged to reporters that while it would be difficult to search the area at night, information led them to believe that Teeky might be in danger, so the search had to begin right away. Volunteers joined the team, but by the next morning when Teeky was still missing, two helicopters went into the air to cover the field. More volunteers arrived on all-terrain vehicles, but it was soon apparent that they would have to turn their efforts to the nearby Brazos River. Five boats were brought in.

On Tuesday morning, Miller’s crew used a side-screen sonar scanner attached to a boat to search under water. The screen showed anomalous images in two separate areas that operators thought were in the shape of a body, so divers entered the swift water to investigate. However, the river delivered no secrets, and by the end of the fourth day, the team had nothing to show. “The water’s deep,” said Miller, “it’s muddy, and the current is strong.” Still, they had another option: a remote-controlled underwater vehicle equipped with a camera. While this device, too, would be ineffective in muddy water, it was worth a try. But after the attempt, they came up within nothing.

By this time, the news was reporting that Carrington was a suspect, not only because he was apparently the last to see young Teeky alive but also because he’d been associated in 1998 with a previous disappearance from the same residence — that of 21-year-old Corey Brooks, who had never been found.

Carrington and Laronald Foy had taken polygraphs, and while she had passed hers, the results of Carrington’s remained sealed. He was detained in jail, based on an unrelated domestic violence charge, while police waited in the hope of finding something that would link him to Teeky’s disappearance. Corey Brooks’ mother (Carrington’s cousin) now became vocal, telling reporters that she believed Carrington had killed her son after a family reunion one night during an argument. She had collected information over the past seven years that implicated him, she said, as well as pointing a finger at others who’d helped him get rid of the body.

Yet Carrington, 31, was not talking, and a week after Teeky had disappeared, she still had not been found. Local law enforcement made the difficult decision to pull their officers off the search, including Texas Rangers who had joined, because their resources were required elsewhere. Miller’s team sought more volunteers to continue the search on their own.

They focused their efforts once again on the river, two miles from the house from which Teeky had disappeared. Continuing with the side-scanning sonar, brought in from out of state, they worried about ominous weather conditions. When it rained, the river rose, picking up speed and force, and thereby increasing the chances that if Teeky’s remains were in the river, she could be swept into the Gulf waters, where she might never turn up. They had to work faster.

A team brought in a cadaver dog trained to alert specifically on the odors of human remains, even in water. The dog went into the boat with the searchers and equipment. Standing at one end, it focused under its handler’s guidance on the water.

Days went by with no indication from dog or device that they were getting warmer, but Miller’s policy is to keep going. On an earlier case, he had manned a search on and off for twenty months, and in the end they did find that person. “We never give up,” he insists.

Still, the weather patterns were disturbing. On Wednesday, December 14, it started to rain fairly hard. The searchers grew increasingly concerned, but they continued to focus on the river. There were not as many of them now, but those who remained were dogged in their determination to locate this girl. No one believed now that Teeky would be found alive, but bringing her body back to her family remained a vital mission.

Then on Thursday, around 1:00 in the afternoon, nearly two weeks after Teeky had disappeared, the dog on the boat went into “alert” mode and shortly thereafter a body surfaced in the river, right alongside the four-man crew. They called Miller, who was on a bridge a mile away with a county investigator, and they sent for the sheriff and medical examiner. When the remains were identified as those of the missing girl, the team felt a grim sense of triumph: Their determination had paid off, but little Teeky had clearly been murdered. The autopsy indicated that she had been beaten with a blunt instrument and stabbed with a knife.

Three days later, Carrington confessed to shooting Corey Brooks in 1998, but he denied involvement in his stepdaughter’s killing. As suspected, he had indeed murdered Brooks during a heated argument, and several acquaintances had assisted him to dump the body into the river, swollen that night from a storm. No one doubted that Carrington had also murdered Teeky, but the family prepared for her funeral without that closure.

Little Teeky Buggs was buried on December 23, two days before Christmas, and seven hours later, Carrington finally revealed how he had killed her. He’d been smoking crack cocaine, he admitted, and when she’d approached him the evening she disappeared, he had hallucinated and thought she was the dead Brooks. So he’d hit her and then stabbed her. He took her body to the same bridge from which he’d thrown Brooks into the river and dumped her. Yet the police had reason to believe that his confession was flawed, and that he’d sexually assaulted the girl. They found the place where he had burned her clothing and his shoes, recovering the knife they believed he had used to stab her, as well as Carrington’s mother’s Lincoln Town Car, in which he had transported the body. They now had good evidence for a trial.

Despite his alleged confused mental state, investigators believe they can try Carrington for assault and first-degree murder. As of this writing, the case is pending, and Carrington remains in jail on $500,000 bond.

In the meantime, Texas EquuSearch remains busy, having completed more than five hundred searches in the half a dozen years they’ve been in existence. Let’s see where it all began.

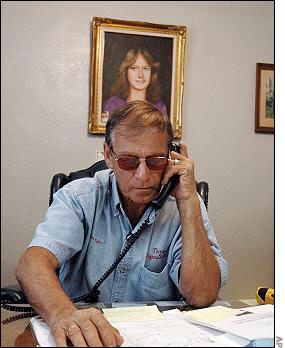

In 1984, Tim Miller’s life was profoundly altered. His daughter, Laura, was missing. The last time anyone had seen the 16-year-old was at a local convenience store, talking on the phone. When Miller discusses what happened to Laura, he likes to start at the beginning, because she did not have an easy time in this world and her murder was just one of many things that had happened to her.

“Laura had a lot of struggles in her life,” he says. “When she was six months old, she got very sick and we almost lost her. She was in a coma for a day and a half, but then she came out of that and her fever went down. She seemed all right, but years later she had a seizure, because the fever had left scar tissue in her brain. So for about seven years we struggled with her seizure problem. Then eventually she grew out of it and became an A and B student. She loved music and sang all the time. She was popular in school and had a lot of friends. It looked like she would be all right.”

But she wasn’t. When Laura was eleven, she came down with the flu, which gave her yet another high fever, with the return of the seizures. “Her whole life was kind of stripped away from her,” Miller muses. The family felt disheartened by this set-back. But the worst was yet to come.

The Millers moved to a new house, and Tim and his wife worked different shifts. One day he went to work, while Laura’s mother took Laura to the payphone at the local convenience store so she could talk with her boyfriend, Vernon. When her mother asked her to hurry up because she’d be late for work, Laura wanted to continue talking. “It’s only half a mile,” she said. “I’ll walk.”

That seemed all right. It was the middle of the day and Laura knew her way back. But she didn’t come back. When her parents returned home from work, she wasn’t there.

“We didn’t think a lot about it,” says Miller. “We just figured Laura got home early, and her and Vernon took a walk. But then Vernon showed up without her and we asked where Laura was. He said he had talked to her on the phone, but he hadn’t heard from her since. That’s when we started getting concerned. We looked all over that night, and then we drove all over the neighborhood.”

The next morning they went to the police department to file a missing person’s report, but the officers dismissed Laura as a probable runaway. Miller said that was out of character for her and also noted that she had a serious seizure disorder and needed her medication. The officers had a response: girls her age were smart and could find what they needed on the street. That made little sense to Miller, but he did not know how to get them to do something.

As he looked frantically for possible avenues, he learned about a girl whom the police had found six months earlier, murdered and dumped somewhere off Calder Drive. He returned to the police station, and the officer with whom he spoke assured him that the murdered girl, Heidi, had worked in a bar, implying that whatever she got she was asking for. To them, it had been an isolated incident.

“Well, then about three days later,” Miller says, “I found out that Heidi had lived only four blocks away from us.” So he went back to the police and asked if they could at least tell him where Heidi had been found so he could go there and search the area himself. They refused to provide information, saying it was private property.

After five days without hearing from Laura, Miller knew in his heart that she was dead. “I didn’t have a clue what to do. I think I tried to drink myself to death. I couldn’t work. I lost my job. Laura’s mother and I didn’t have the best relationship and it certainly got worse. Every time our phone would ring, or someone would drive by the house slowly or knock on our door, I got heart palpitations. I didn’t know if they were bringing me good news, that they’d found Laura and were bringing her home, or if they were bringing bad news that she was dead.”

But for more than a year and a half, no one brought any news.

A year and a half dragged by with no information, and Miller was so depressed he contemplated suicide. Finally, he checked himself into a hospital for six days. That’s where he was when he finally received some information: In the newspaper was an article that reported the discovery in a local field of the remains of two females. Some kids riding dirt bikes had smelled a foul odor in the area of Calder Road. The corpse they found had been dead four or five weeks, so it was fairly decomposed. When the police went to investigate, about six feet from that body was a set of skeletal remains. That meant that within two years, three dead girls had been left there. Apparently a serial killer had used the area as a dumping ground.

Laura’s mother went down to the police station and said, “One of those girls could be my daughter.” They requested some of Laura’s clothes for a hair sample and her dental X-rays. After an analysis, one set of remains proved to be Laura’s.

“I blamed the cops,” Miller remembers. “I didn’t think they were doing their jobs. If they would have gone out there the first day I asked them to, Laura would still have been dead, but there might have been evidence.”

Miller went into another tailspin. He felt angry and guilty all at once. “I was the father,” he recalls about his state of mind, “I was supposed to protect her and take care of her, and I had failed. I failed by not doing the right job, by not searching. I failed by not going to Heidi’s family’s house to find out where they’d found her. If I would have done that, maybe I would have found Laura tied up; maybe she would have been alive and I could have saved her. Or maybe I would have found her and it wouldn’t have been months after the animals got to her. I beat myself up because I didn’t do enough while Laura was missing.”

At the same time, he felt a sense of relief. “Now at least I knew. I didn’t have to worry about the heart palpitations every time the phone rang.”

Still, the discovery and identification were only the start. Next came the investigation. “We had to answer questions about who Laura’s friends were and who she hung out with.” Worse, the police withheld information. “Even at the time she was found, they would not tell us where. The newspapers said it was the same field where Heidi had been found, but they wouldn’t show us where it was. So Laura’s mother and I went out and we found it on our own. We walked the fields and finally saw the little flags marking the crime scene. I learned then that her body had been scattered over a twenty foot radius. I was speechless at that time, just numb. I just couldn’t believe it.”

Miller and his wife wanted Laura’s remains for a burial, but the coroner asked to keep them a while longer, and Miller agreed. He wanted to learn how Laura had died, but to his chagrin, the police kept the remains for another three years. But that still wasn’t the end of it.

The Millers were finally allowed to bury Laura, but when they received the autopsy report, they were concerned enough about what it said to exhume the remains. They discovered that they had received only 28 bones, and then realized that some of Laura’s remains had been sent to a medical facility for research. Although the officials said the remains had been sent in error, it was clear that they had profited, so Miller hired an attorney and sued them for $16 million. He won, but they appealed. Miller just wanted all of Laura’s remains for burial, so he agreed to drop the suit if they returned the bones. “Finally we got to bury her and really say goodbye.” But it had been an emotionally draining ordeal, and yet one more episode of police misconduct in the case.

Miller also learned that Laura and Heidi had both disappeared from the same convenience store pay phone, which meant that, had the police paid attention to him when he’d first filed the missing person’s report, Laura might have been found alive. This realization made the ordeal much more painful. The police response clearly had been unconscionable.

Then there was more turmoil. As often happens when a child dies, Miller and his wife separated and divorced. He entered Alcoholics Anonymous and received counseling. “It was very painful but each day got better, unless there was new information or there were new leads.” Then he’d remember and feel the pain all over again.

By 1991, he had stabilized, but then another set of female remains was found in the same area off Calder Road. The police developed a suspect, who worked for NASA, but in the end, the case went nowhere. Miller did not get the resolution for which he hoped. But his ordeal did evolve into an unforeseen benefit to himself and many others.

“After Laura was found,” Miller recalls, “there was a rash of murders of young girls in the area and I would go to the spots where they had been found to see if there was any similarity in the area where Laura was found. Then I started meeting with several of the families. It was pretty painful.”

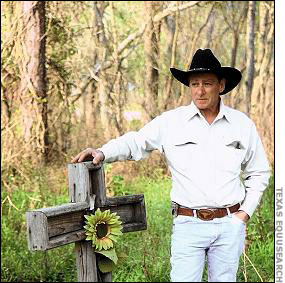

The disappearance of Laura Smithers in 1997 in the next town gave Miller the idea for an organization that would assist the families over and above what the police were able to do. For a few days, he assisted in the Smithers search, but it was more than two weeks before a man walking his dog found her remains. Her family grieved and then founded the Laura Recovery Center, so Miller volunteered there. While working one day, he got into a discussion with the center’s director, who suggested to Miller, a horseman, that he start a mounted search-and-rescue operation. Something like that would be quite helpful in a state like Texas.

Miller put out the word in August 2000 and within a few months, he had 45 members coming to meetings once a month. Most had horses. But as word about their activities spread, the organization shifted. “People started coming who had boats and who were certified rescue divers offering up their resources and wanting to join,” says Miller. “People even came with planes, or a helicopter. Many people came with four wheelers, and then we got our own infrared and night-vision equipment. We grew past just the horses and ended up with more resources than most places have.”

As more people learned about them, they received calls from all over the state and then from out of state. “Even after Laura’s death I didn’t realize just how many people were really missing,” says Miller. “I remember the seventh or eighth search we got called into was for Julie Sanders, about 250 miles away. We were still fairly new and we had no money, but I went up there and put the search together. At the end of the first day we found Julie’s body.”

Texas EquuSearch (TES) is now among the few specialized volunteer teams that offer law enforcement assistance in undertaking searches for missing persons presumed to be dead. Another such team, based in Colorado, is NecroSearch, a group of engineers and scientists who also tackle cases in difficult terrain. However, TES is set apart from any other in that they utilize the skills and abilities of horseback riders, they can quickly marshal a large force of volunteers, and they’re flexible enough to accept assistance from a variety of disciplines. Funded solely by donations, they sometimes operate at a deficit, but they keep going, because Tim Miller can’t imagine telling a family in need that he does not have the resources to assist.

On the Web site, www.TexasequuSearch.org, the organization offers the following statement:

“You will find our organization to be compassionate, dedicated and professional. We believe that we can better ourselves by working together to help the community and people in need. Many of our members are trained in various rescue and life saving skills such as CPR, advanced lifesaving skills and field craft. Our members come from all walks of life. We have business owners, medics, firefighters, housewives, electricians and students on our team. Our resources range from horse and rider teams to foot searchers, water (divers, boats) air (planes, helicopters), dog teams (air scent, cadaver and tracking) and 4×4’s. We have also utilized infrared cameras in some of our searches.”

Sadly, they receive plenty of requests.

Since the search for missing persons comes under the jurisdiction of local police departments, especially when foul play is suspected, Miller is always cautious, because the potential is high that the officials who are paid to do this work may be insulted if he goes back over their ground. Yet even with their best efforts and resources, sometimes the official searchers do miss bodies.

“We came into a search in Austin for a man named Henry,” Miller says. “They’d found his car abandoned and he’d been missing for six days.” TES was invited in and Miller had mapped a dozen areas that he believed ought to be searched. The officials had used cadaver dogs to target one area for a SWAT team, which they wanted to keep for themselves, so Miller said that was fine; he had other areas on which to focus. The officials spent two hours and then “cleared” the area. They had found nothing.

But Miller wasn’t satisfied. Two hours wasn’t sufficient time to do a thorough search, even with dogs. He asked if he could send in his team to the same area, telling the officer in charge that since they had more people, luck might be on their side. The officer gave him permission but believed he was wasting the team’s time. He was wrong. It took only ten minutes before the TES volunteers found the body, leaning against a building in plain sight. The cadaver dogs had been with six feet of it but had not picked up the scent.

“Our strength lies in numbers,” says Miller. “The more people you have out there, the better chance that someone is going to see something.”

Before describing another search, let’s look at what being a volunteer involves.

According to Miller, volunteers generally receive training on the spot, which means they learn how to place evidence markers or flags, as well as how to communicate with search coordinators. In the event they find a body, they’re instructed, they should not panic. They’re never to approach or touch a found body. In the event they see one, they are to stop immediately and walk backward in their own footprints so as not to further contaminate the scene. (Not all bodies are victims of crime, but each discovery is treated as a potential crime scene.) They must then seek official assistance immediately. Several law enforcement officers participate on the teams, as well as a few forensic scientists, so there are often volunteers who know the protocol, but large-scale searches are comprised of mostly lay volunteers, some of whom may never have seen a body before.

Those who volunteer on horseback must demonstrate skilled horsemanship and their horse must be able to perform and to tolerate several things. The full list is posted on the Web site, and among the items are:

-

The horse must be able to walk, trot, canter, stop and stand under control from either direction in the arena

-

The horse should stand quietly while tied or being held, mounted or dismounted from either side.

-

The horse should allow the rider to hold at least two other horses while mounted, and stand calmly.

-

The horse should be able to negotiate obstacles in an arena that demonstrates the rider’s control, with the rider being able to drag an object using a rope, back the horse in an “L” pattern, walk the horse over a large plastic tarp, and open a gate from horseback.

-

The horses should be able to calmly negotiate a bridge, thick brush and water, alone or with other horses present.

Volunteers without horses must be able to follow the orders from a search director and to work with whatever equipment they bring, whether it’s an all-terrain vehicle, a helicopter, a methane detector, or a high-tech infrared system.

Miller believes that, while the organization has about 660 members nationwide, they have used more than 38,000 volunteers. Since 2000, he estimates they have conducted around 525 searches, bringing home at least 100 people safely, including children. In fact, approximately 72% of the searches have resulted in getting someone home or finding the remains — an impressive result.

Among those who have gotten deeply involved in the efforts of TES are the personnel who hold the place together, ensure that fund-raisers are organized, answer phones, direct volunteers, talk with families, and represent its work to the media. Miller relies heavily on Search Director Joe Huston, and search leaders Steve Pitzer, George Adlerz, Darryl Phillips, Ted Tarver, and Renee Utley. In the office, volunteers coordinate the efforts to distribute resources, especially when there are several searches going on at once.

Barbara Gibson, one of the key office staff members, got involved in TES after experiencing the back-to-back deaths of five people in her family. This made her acutely aware of the anguish that people go through when they lose someone they love, so she decided to volunteer to assist with the organization. “I had never lost anyone that I loved before,” she commented, “and the grieving process was staggering. Tim Miller was the one that helped bring me out on the other side of it. He’s probably the most compassionate man I’ve ever met.”

Also assisting in the office are George Adlerz, Cindy Wisdom, Barbara

Collins, and volunteers who pop in when things get overwhelming. “It’s a major

team effort,” Gibson says. She herself may work on anything from marketing the organization, answering phones, coordinating media, organizing fundraisers, and keeping the office in order, but her passion is doing research on cold cases. She also looks to the extra touches. She was so moved by Miller’s story of loss, for example, that she co-authored “Laura’s song,” which plays on a DVD about the origins of TES and its cases. “We wanted a song that didn’t pull any punches as to what families of missing persons go through,” she explains, “and to send the message to not give up.” (This DVD will be available on the Web site.) Gibson had walked with Miller along Calder Road, where Laura and the other girls had been left, and says that Miller often receives a strong impression there of Laura speaking to him from beyond, urging him not to give up.

“Tim has created so much more than just a search organization,” Gibson adds. “It’s a place to heal and rechannel your energy into helping others. Many of our members are the families of missing persons whom we found deceased. Collectively, I feel all of our broken pieces help to make us whole again and better people than we were before.”

These members find solace from TES, and even after their loved ones are found, they keep returning to the Web site to follow the progress in other cases of missing people. Some offer to assist with such functions as running a newsletter, which may turn into a slick, full color magazine.

“There’s an unusual synchronicity that flows through our work,” Gibson affirms. “Whatever it is that we need on a given case seems to appear at the right time. I’m always meeting people at random who wind up playing a needed role at some point.”

When asked why she puts so much effort into the organization, she points to the many letters of thanks and the awards from other organizations that recognize how they have filled in holes for the families and delivered a needed psychological respite. “The most beautiful aspect of a search,” says Gibson, “is seeing a community pull together to

help find someone they don’t even know. It becomes very personal to everyone

involved. Tim has harnessed the power of compassion and created a means for

others to unite and reach out to those in crisis. People truly do want to help

their neighbor.”

Summing up her feelings about the work, she says, “It’s a place where heart and soul overcome heartbreak and despair through the unity of spirit among our volunteers. I’ve never seen anything more beautiful than the selflessness and determination of our volunteers.”

Among the most impressive efforts are the people who are willing to leave their homes and work in places far away, for a considerable period of time. The synchronicity that Gibson mentions has occurred in surprising ways.

On December 26, 2004, tsunamis swept across the Indian Ocean, spawned by a magnitude 9.0 earthquake off the coast of Sumatra. Aside from Indonesia, the island nation of Sri Lanka suffered the most casualties. More than 31,000 Sri Lankans died, and throughout Southeast Asia, the tsunami’s overall death toll topped 200,000.

An organization in Sri Lanka contacted TES, asking for their assistance to search for missing people. “We had no clue how we were going to pull that off,” says Miller, “but we did. I took 14 people to Sri Lanka for 14 days. In the first hour and 15 minutes, we found eight bodies. While we were there, we adopted a village, and when we left, it was cleaned up and ready to rebuild. In all, we found over 220 deceased people.”

In the U.S., they were close to the state of Louisiana when Hurricane Katrina wiped out New Orleans and destroyed many homes, so once again TES pitched in. “We adopted a family after Hurricane Katrina. Donations come in to help, but sometimes I don’t know how we keep going, paying the phone and electric bills. God just blesses us. We keep giving, but we keep getting in return.”

They operate on donations, fundraisers and the occasional grant. Members help, as do volunteers who participate in searches. Yet until they got involved in a high profile case, most people had never heard of them. That changed one day with a phone call on Father’s day in 2005. It was from Paul Reynolds, the uncle of Natalee Holloway, missing in Aruba.

“I don’t know if there is any way you can assist us,” Reynolds said, “but we really need your help.” He lived in the Houston Area, so Miller agreed to meet with him to discuss the situation. He already knew from news reports that the search was in Aruba. Since he’d led a search in another country, he was ready for the challenge, except for one thing: “We only had about $1,600 in our account.” He knew that wouldn’t get all the people he’d need to Aruba, but he told Reynolds that he’d go. “I took money from my company, off a job I’d been working on, but then the media did stories on us and we started getting donations, including plane tickets from Continental. I was able to take 115 people to Aruba with every resource you can imagine. We took the best of the best.”

He would need it.

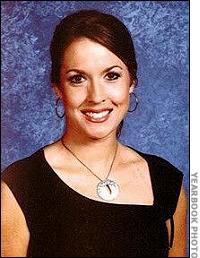

Eighteen-year-old college student, Natalee Holloway, had disappeared while visiting on a chaperoned post-graduation trip. From Mountain Brook, Alabama, near Birmingham, she was last seen on the Dutch-controlled Caribbean island of Aruba on May 30, 2005. More than 100 other students had come, so it was difficult to keep track of them all, and Natalee ended up on her last night at the tourist bar, “Carlos ‘n’ Charlie’s” with three young men, Joran van der Sloot, and Satish and Deepak Kalpoe. Witnesses had seen them get into Deepak’s car. During the evening, Natalee had reportedly acted rather wildly at the bar and she appeared to go willingly with the three men.

The next morning, Natalee did not arrive at the airport for her return flight home. Someone checked her rooms at the Marriott Hotel to see if she was there and found her clothing and personal items, packed in her luggage, as well as her cell phone and passport. The police checked footage from the hotel’s security camera, but there was no indication that Natalee had even returned to the hotel the night before. Nevertheless, the three men she had been with, when questioned, insisted they had dropped her off near the hotel around 2:00 A.M., and she had been intoxicated. They had seen a black security guarded assisting her.

Reports of her disappearance were carried in papers all over the U.S. and the case was discussed on numerous talk shows. Natalee’s stepfather and mother, George “Jug” and Beth Twitty, who flew immediately to the island, insisted that Natalee was a responsible, bright honor student who had been accepted into pre-med studies at the University of Alabama. She was not, as the papers painted her, a wild party girl. Searches were conducted and a great deal of publicity was brought to bear on the local authorities to find the girl, but she failed to turn up. The police went to the Aruban residence of the van der Sloots and interrogated the young men, who finally admitted they had taken the girl to a lighthouse to make out before dropping her off at her hotel. They insisted that they had not had sexual relations with her. And they were not the only suspects.

In all during the course of the investigation, eight men were arrested, including Natalee’s three escorts, two security guards, Joran’s father and neighbor, and a disc jockey. By September, all were free to go, although they remained suspects. Various witnesses reported seeing the three young men doing suspicious things on the night in question, which undermined their stories and led to the fruitless search of a lake and a landfill. Planes equipped with infra-red sensors also failed to record anything of value.

However, tests run on Natalee’s toothbrush yielded the DNA of a male, but it did not match any of the young men with whom she was last seen. That meant another suspect, as yet unknown, was in the picture. Rewards were posted that grew to one million dollars for her safe return. Still, there were no productive clues.

Miller’s organization got involved in July 2005, helping to search the area where the small lake by the Marriott had been drained, and to scan local sand dunes with radar equipment. Nothing turned up and Natalee remained missing. Finally, TES had to return to the States. Miller wasn’t happy, and he was determined that he would be back.

On January 13, 2006, he returned to Aruba to work with Jim Whitaker and Aruban Chief of Police Gerald Dompig to coordinate a new search. Information had surfaced that a fisherman’s crab trap, large enough to contain a human body, had been stolen the night Natalee had disappeared, so it seemed possible that she had been killed, placed in the trap, and taken far out in the ocean to be dumped. Miller agreed to return in a few weeks with sophisticated equipment for a deep water search. If she had in fact been taken out that far, the cold water would preserve her remains.

Underwater searches require specialized knowledge. People who do this work must know the effects of different types of water on evidence, including corpses. They must possess extensive diving experience, knowledge about what to look for under water, and skill with the equipment involved. As well, they must know how to document and handle evidence within the protocol for that context. For example, there is a difference between rescue and recovery in a placid lake than in the ocean or in swift-running water.

If this search fails to turn up Natalee, the searchers will need to look for other options. As Miller says, TES never gives up. They’re in this case now and they’ll stay there for as long as it takes. In fact, Beth Twitty has been so impressed with their help that she volunteered to assist on the search for yet another missing woman.

Immediately after returning from the January Aruba trip, Miller went back to Ocilla, Georgia, where his team was prepared to make yet another effort in the search for a missing high school teacher and former beauty queen, 30-year-old Tara Grinstead. They had been involved in this case since December.

According to Crime Library reporters Steve Huff and Seamus McGraw, who covered the story, Tara apparently vanished on October 22, 2005. She had returned from assisting young girls at the Sweet Potato Festival in Fitzgerald, Georgia, and it appeared that after dinner with friends, she had made it home around 11:00 p.m. She turned on a nightlight, plugged her cell phone into a battery, and removed the clothes she had worn that night. Her absence was noticed on October 24 when she failed to show up to teach her ninth grade social studies class at Irwin Count y High School. She had called no one to say she was ill, and although she had once left school early over emotional issues, it was not like her to fail to report in. While people initially said she had no reason to just pick up and leave, subsequent discoveries indicated that the idea was not out of the question. There were reports that someone had seen her as late as Sunday afternoon, but skipping church, which she had done, was out of character for her.

Recently, Tara had broken off her six-year relationship with a boyfriend, Marcus Harper, and she reportedly struggled with conflicted feelings over its failure. In addition, she’d had to deal with a former student who had developed a strong crush on her, and she was suffering from the stress of taking classes to prepare for a doctorate. There were conflicting reports that she might be suicidal: Harper said she was, while others insisted she was not.

After Tara was reported missing, investigators went into her home. There were only a few hints that something might be wrong: some small items knocked over, missing earrings that she had worn on Saturday night, her car seat pushed back uncomfortably far for a five-foot-three woman, and a latex surgical glove lying on the lawn. But she was not the type of person to just run off. She was in a graduate program, well-connected to the community, loved by many, and known to be responsible. According to McGraw, “While [people in the community] acknowledge that that it is plausible that the young woman might have been abducted, or in the worst case, even killed, there is also the possibility that she could no longer stand the stress of her life, her grueling study schedule, her demanding profession, her increasingly unsettled personal life.”

Marcus Harper, a former Ocilla police officer, became a suspect, although he had been in the company of another police officer Saturday evening and Sunday morning. He denied reports that he and Tara had been fighting before she disappeared.

To get more assistance, the local police called in the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. They also used K-9 units and helicopters, and several Internet Web logs devoted to missing persons added their first entries. In addition, a contingent of volunteers helped to search the entire county for her, but they came up with nothing. After two weeks with no leads, the official search was called off, but Tara’s family and many volunteers vowed to keep going until they had searched every possible area in the county.

TES came into the search, as reported on December 5, 2005, and Beth Twitty eventually joined them, assisting with organizing the 500+ volunteers who came to help.

Miller brought to the Grinstead case a sense of organization, as well as special technology that had not yet been used in the case. His people organized the volunteers into teams to efficiently search specific areas. He told the various teams that by this time, the chances of finding the missing woman were low, but the search had to be undertaken with care. It was easy to get distracted, but that was to be avoided, because a search required full concentration. He knew well enough how even trained officials had missed bodies only a few feet away.

Since they were going to look into the many abandoned wells in the county, he had brought underwater cameras that operated on 100-foot long necks to go into places that could otherwise not be searched with flashlights or the naked eye. On hand were representatives from companies that had equipment generally used for other purposes, who believed it could assist in a forensic investigation. A methane gas detector, for example, provided by Health Consultants, Inc., might pick up the odor of decomposition far down a well the way it detected gas from broken lines.

The teams searched all day, some going all weekend, with no indication that they were any closer to finding the missing teacher. It was disheartening for some, who wanted desperately to know what had happened to her. But they all knew the odds were against them. When the search was finally called off, Miller went home to think it through. He was not giving up. He then returned after his second trip to Aruba to reconnoiter.

“We have some cadaver dogs in the search, including water cadaver dogs,” he says, “and we had four dogs alert on a spot in Georgia that we’d gotten a lead on. This house out in the country had caught on fire a few days after Tara had disappeared, and the fire was from arson. There was a small lake on the property and the dogs all alerted on an area at that lake.” So he set his team to work to search it.

As of this writing, Tara and Natalee are both still missing. In fact, there are some 60 open cases in which TES has been involved. While Miller believes that many of the missing are dead, he holds out hope for the others.

When asked what criteria he uses to decide whether to devote resources to a case, Miller responds that Amber Alerts come first: missing children may be found alive, rescued, and returned to their rightful families. After that, the priority goes to Alzheimer’s patients or people who need medication who have wandered away. They’re often found within hours. Then TES will investigate other missing people, but in the case of apparent runaways, they will generally advise parents on the work they must do, and will distribute fliers and place notices on the TES Web site, www.Texasequusearch.org.

What often upsets Miller is that minorities often do not get the attention from law enforcement or the media that they deserve. “When Elizabeth Smart disappeared,” he says, “it was a zoo of a media show. Two weeks later, an FBI agent asked for my help in the case of a missing four-year-old black girl. We went over with a team, and at the end of the first day the police chief decided to call off the search. I didn’t want to tell him how to run things, but I didn’t want to call off the search.”

Miller was disheartened that for several weeks the search had been going on for Elizabeth Smart, with daily media attention, while no one seemed to care for more than a day about the missing black girl. The sheriff allowed him to keep going, and on the fourth day of the search, the girl’s body was found. She had been raped and murdered, “and it barely made news in Houston.”

Others share his concern, and between volunteers, bloggers, Web site owners, and others with their own resources, perhaps some of the forgotten people will receive more attention.

TES participates with a blogging site, Scaredmonkeys.com, which among other things lists cases of missing persons and news reports that follow the progress of various searches. The Scared Monkeys cofounders, Red and Tom, came across TES as a volunteer was posting updates on the Aruba situation, so they invited TES to use their site. They added a Missing Persons board, consisting largely of people on the TES list, and did a live phone interview with Tim Miller. Then Red was invited along to Aruba as one of the volunteers. That gave him added incentive to keep the stories alive.

“Covering the case was one thing,” says Red, “in meeting, talking and discussing issues with the Texas EquuSearch volunteers. However, the story took on a whole new emotional and personal perspective when I spent ten days in Aruba searching in the landfill, searching with dog teams and searching the van der Sloots neighbor’s property. Digging in a landfill side by side with the TES volunteers and with family members such as Dave Holloway gave new meaning and a perspective to missing person cases that I could never have experienced by just writing about them. To physically be a part of the search team in the most foul-smelling, heat-exhausting, dirty landfill, and working side by side with Natalee’s dad was an experience that will last a lifetime. What transpired was an understanding of the perseverance and dedication of volunteer searchers and the will and determination of a family to find their daughter.”

Bloggers are welcome to post information or comments on the Scared Monkeys site about any cases in which they have information or leads. (During the coverage of Natalee Holloway search, the site logged 1.4 unique visitors per month.) Many items feature the work of TES, and Scared Monkeys posts announcements to assist TES in recruiting volunteers, such as the following notice from January 26, 2006: “Texas EquuSearch Director Tim Miller is requesting volunteers for the search of Robin Turner on Thursday, January 26, 2006, at 10 A. M. Tim will need horses, 4-wheelers, and ground searchers. The command center is located at the Forest North Park on the corner of Peach Stone & Roseville in Spring, Texas.”

Robin required seizure medication, and since she had been missing for ten days already, the need to locate her was urgent. People responded and TES volunteers searched for only two hours and fifteen minutes on January 26, the same day the notice went up, before locating her body. Sadly, she might have been found alive had an organized search commenced immediately upon learning she was missing. But that requires letting the public know that these resources are available. Those who do know are doing their part to spread the word. “Scared Monkey Missing & Exploited looks to the future to continue to aid as a resource for missing persons,” Red states, “and potentially partner with others to effectively cause changes in how cases will be investigated. Missing person is a major issue of our day and no one should have to be victim to this crime or horrible tragedy.”

Tim Miller has come a long way since his daughter was murdered two decades ago. Besides finding the dead, he has helped to locate people who wandered off and has returned many children to their parents. He’s met many wonderful people as well among those who have volunteered to assist.

“I feel like the most blessed person in the world,” he states. “I can look back at Laura’s death, which took me so long to try to make any sense out of, and I can say, ‘Laura, your death wasn’t in vain.’ It was because of her death that we have saved many lives and brought closure to many families. I miss her every day, but a lot of good has come out of her death, too.”

Miller’s ultimate goal is to acquire half a million members nationwide for EquuSearch, so when the need arises in any given state, they can get people from around the country on site immediately. With the number of people who respond to the plea for volunteers with each new search, he’s well on the way to achieving that goal.

Donations can be sent to:

Texas EquuSearch

Mounted SAR Team

P. O. Box 395

Dickinson, Texas 77539