2 LA teenagers murdered in a sandwich shop — Grim Discovery — Crime Library

Watch LA Forensics Wednesdays at 9:30pm E/P to learn more about this case and others like it.

[Note: A number of names have been changed to protect identities]

It was around half past one in the morning on June 30, 1991. A woman named Rebecca who lived in an apartment in the middle class college town of Northridge had directed her boyfriend to park in the Sandwich shop lot on Devonshire Street and Zelzah Avenue, since parking on the street was tight. She happened to look inside the shop, still apparently open, and saw three men inside.

Two were white, while a black man at the counter seemed to be placing an order or talking to them. He held something that Rebecca thought resembled a metal bread pan. As she walked away from the shop, she heard an explosive noise and assumed the pan had dropped to the floor. When she glanced back, she saw only the black man and he was jumping over the counter or going around it, so she believed the three men were just having some fun. From where she was, she could see the LAPD Devonshire Station, so she never considered she was witnessing a crime in progress.

A few minutes later, as reported in the LA Times, at approximately 1:45 A.M., a man approached the shop to order a late-night snack. As he reached for the door, he saw someone lying on the floor and then spotted a pool of blood around the fallen man, so he ran to call the police from his car phone.

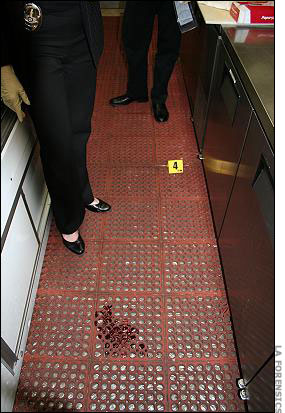

Officers arrived at 2:00 A.M. and found a body, identified as Brian Berry, 18, lying in front of the store’s counter. An entry wound to the cheek and gunpowder stippling in his eyes indicated he’d been shot in the face while looking at the gun perhaps taken by surprise. He’d also been shot a second time, in the side of his head. But he was not the only victim. As police looked around, they found another young man. Behind the counter near the cash register, nineteen-year-old James White lay facedown in a puddle of blood. He was moaning, apparently still alive; an ambulance was called to rush him to the hospital. Then the officers prepared for the gruesome task of photographing and mapping the scene.

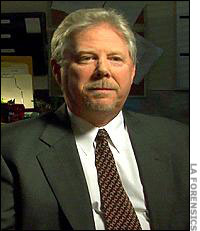

The medical examiner, Dr. Christopher Rogers, came in to check and remove the body of Brian Berry for autopsy, while homicide detective Terry Richardson and detective Peggy Moseley took over the scene. The crime looked like an obvious robbery; the officers noted that the cash register was open and the tray empty, with only a few coins left inside. More interesting was the empty floor safe in a room in the back of the store. This indicated to them that the perpetrator had known about its existence and location. That could narrow their suspect pool. The fact that the perp had chosen a shop so close to a police substation suggested either a degree of rash confidence or familiarity with the area.

A security bar placed across the back door had been removed and set aside, an obvious exit. The officers went through the door looking for tracks or other items of evidence and came into an alley. A few yards away lay a plastic Sandwich shop bag that contained a wrapped sandwich. Careful not to touch it, they mapped the scene, inside and out, and let the Scientific Investigation Division take it over for evidence collection.

The SID technicians began dusting everything inside the store for prints, but they knew a public place like this could pose difficulties because so many people have touched things. However, they spotted a partial shoeprint on the counter, going in a direction that indicated someone jumping up to get behind the counter. They photographed this and then carefully made a lift. If they developed a suspect, they could get his shoes and check for a match. They collected several bags of chips that lay on the counter, picked up the dropped sandwich from the alley, and found three scattered shell casings from a .380 semiautomatic handgun, but did not locate a weapon. In addition, they discovered that the alarm system was defunct. Even if James White had pushed the button, it would have done him no good.

Detectives hoped that the critically injured James might be able to give them a description of the perpetrator, so they checked on his progress at Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills.

Unfortunately, James White had died about four hours after he was shot. He’d been held on life support just long enough for his parents to come in and take their leave. The police had known he probably would not survive long with a bullet in his brain, but they’d held out hope he might revive long enough to describe his attacker.

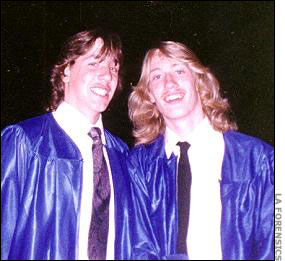

The following day, as the police proceeded with the investigation, the Los Angeles Times reported that the victims had been childhood friends, having met each other in the fourth grade. With a third friend, they’d been known around school as the Three Musketeers. Brian Berry and James White did everything together and each of their families considered the other boy to be like another son or brother. One of the most deeply affected by the tragedy was Brian’s twin sister, home alone that night when Detective Richardson delivered the bad news. She later said that she had felt a sudden pain in her head that night and believed her bond with her brother was such that she had experienced him being shot.

James had been the eldest of three children and he loved music. He had hoped to get certification one day to teach social science. Both young men had graduated from Granada Hills High School and James was earning money to go to Pierce College, while Brian worked as a welder in a trailer hitch shop.

James had been employed at the Sandwich shop for only a few months. He had been cleaning the place in preparation for the 2:00 A.M. closing, and Brian had dropped by to chat and assist, so they could hang out together afterward. Then the shooter came into the store. By all appearances, they had cooperated with his demands, emptying the cash register and opening the safe. Nevertheless, he shot them both in the head, execution style, before fleeing the store.

With James’s death, Dr. Rogers had a double autopsy to perform. Although both victims had head wounds, a full autopsy was in order to determine the precise cause and manner of death. The manner of death was clearly a homicide. Time of death was being established with shop records, but the actual death mechanism meant looking for the physiological failure in the body that had caused death, such as lack of oxygen or loss of blood.

Autopsy reports indicated that Brian had been shot once below the eye in the left cheek from close range, from about a foot or so away, and then shot again, with the gun pressed against his head above the right ear. James, too, had a contact wound, but this one was more chilling. The killer had place the muzzle to the crown of his head to shoot him from above, probably while James was kneeling. All three bullets were recovered from the bodies. There were no exit wounds.

Friends who gathered around the shop on Sunday after hearing the news told reporters that Brian and James had been great guys, loyal and generous. Brian often came to the sandwich shop to visit James, and he pitched in, unpaid, with cleaning duties.

Shop employees said the area felt safe to them, even when they closed alone, because of the police presence close by. Officers frequently came into the shop and they kept an eye on the neighborhood. A patrol car passing by had even foiled a robbery attempt only months earlier.

Nevertheless, someone had certainly been bold and that person was roaming free. Whoever he was, he would have cash. The shop’s manager said that the safe had contained about $200, but after looking at the evening’s receipts, he estimated the thief’s total take at around $580.

With the evidence collected, the investigative strategy for crime reconstruction and learning about the shooter included the following:

- Dust the store and potentially related items for fingerprints that could be compared with a database of prior offenders

- Lift and preserve the shoeprint for later comparison

- Analyze the spent shell casings for later comparison

- Use autopsy results for how and where each victim was shot

- Look for possible eyewitnesses

- Determine if there were any obvious suspects, such as former or present employees with a grudge or enemies of the victims

From among these activities, investigators hoped to learn enough to be able to arrest and convict the offender. It was an unusual type of crime for the area, and the pressure on was from local residents to solve it.

Northridge was situated at the northwest end of the San Fernando Valley and was considered a safe place. However, by the end of that year, two LA Times reporters would quote statistics that indicated things were changing. “As of December 7,” stated Berger and Connelly, “according to the most recent police figures, 137 people had died by violence this year in the Valley a 14.5% increase over last year.” They then added six more murders from that weekend, and said that in the Valley over the past decade violent crime had increased by 38%. Even so, they also found that the police there had a good record for arrests.

Yet there was another issue to consider as well. During the year prior to the sandwich shop murders, some 50 sandwich shops in the Los Angeles area had been robbed. The incident in Northridge thus precipitated a meeting with shop owners about how they could make their businesses safer. Richardson and Moseley knew that if the Northridge robbery-homicide was in that series, it had been a random hit by someone not associated with that particular store. Thus, identifying the perpetrator would be much more difficult. Since no one had been killed in the other robberies, they continued to hope their situation would be resolved locally.

Among initial suspects was a man who was arrested for robbing a gas station down the street from the sandwich shop. However, his fingerprints did not match those lifted in the shop. The night manager was interviewed, since he had taken the night off, but he was not detained as a suspect.

While detectives asked for a list of present and former employees, especially those who might have returned to rob it, they learned that turnover at shops like this is high. They received dozens of names, but the franchise owner could think of no one who stood out. Two clerks had been let go in October on suspicion of theft by one of them, but neither was directly accused. The detectives made a note of their names.

The cash register was taken for analysis. Its last registered transaction had occurred that morning at 1:32: a turkey and bacon sandwich, a seafood sandwich, and two tuna salads. According to the tape, the items had not been paid for. Thus, it seemed very possible that the shooter had handled the dropped sandwich, since it had been turkey and bacon, but it was not easy to lift fingerprints from plastic bags, so latent print technicians concentrated on other items first. When they got few prints from the cash register, chips bags collected from the counter, or coins from the register’s drawer, they turned to the plastic bag. Feeling pressure to find something that would nail a suspect, if identified, they worked cautiously.

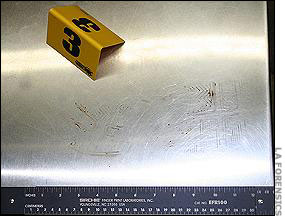

Scott Hurwitz, a latent print analyst, refrained from applying the typical method of black fingerprint powder to make prints on the bag visible, for fear of smudging them. He turned instead to a different type of processing cyanoacrylate fuming, also known as Superglue fuming, which is done inside a special hood. Discovered in Japan in 1978, it is a chemical method that reacts with acids and proteins in the sweat that leaves the print impression.

“It’s heated up,” Hurwitz explained, “and the fumes will collect onto the surface where the fingerprint is.” The glue hardens and the print is thus more easily preserved than with a powder. With this method, SID managed to get a good impression of a left thumbprint and a left index finger on the bottom of the bag. However, after putting the impressions through the AFIS database, where they were compared against millions of others in digital storage, they found that no one with a prior criminal record had committed this crime.

Nevertheless, the detectives believed they had a promising case. “We had prints,” said Officer Moseley, “and we had ballistics. It was a good crime scene. It had a lot of evidence that could be processed.”

They would soon have more.

Officers and volunteers canvassed the area for witnesses anyone who had seen anything between 1:20 and 1:45 A.M. that Sunday morning. A reward of $35,000 was posted for information leading to an arrest, with $25,000 from the LA City Council and $10,000 from the Sandwich shop Corporation.

Several people came forward with tips, but none provided the right kind of information. The police only knew from the bullets the type of gun they needed to find in the killer’s possession. They continued to knock on doors and talk with people in the streets.

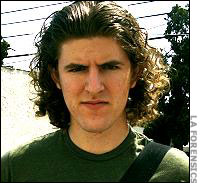

Then someone offered what looked like solid information. The woman who lived in the nearby apartment building, Rebecca, heard about the robbery and double homicide. When police knocked on her door, she described what she had seen that night as she walked home. She now knew she had witnessed the actual robbery and heard at least one murder occur. She was not confident she could identify the man who had been in the shop, since she had only looked quickly at him, but a few days later with the assistance of a police sketch artist, she managed to provide enough detail for a composite sketch. The man she recalled was thin and scrawny African American. He’d been in his early twenties, was about five foot eleven, and had large lips and short-cropped hair. His skin color was not very dark and he wore a white T-shirt. The composite looked close enough like the man she had seen that she affirmed it was accurate.

The police made posters from the drawing and hung them around the neighborhood. Several people called to tell them it looked like a man named James Robinson. He lived there and had once worked at the shop. In fact, he was one of the two men who had been let go in October.

These were good leads, but by that time, the detectives already had a better one.

On the fourth day after the murders, Detective Moseley received a call from a woman who said her name was Karen and she might know something about the homicides. However, before she would reveal anything, she said, she first wanted to know the caliber of the weapon used. Moseley told her they could not give out that kind of information, so she hung up. It was frustrating for the police. They could not understand why someone would place such a condition on providing assistance in an investigation this serious, but there was nothing they could do but wait and hope that she had a change of heart and called back.

Two days later, they received a second call and again refused to provide the information requested. Again, she hung up. Then she called a third time on July 8, insisting she might know who the killer was so they decided to take a risk and tell her the type of gun they were looking for. To their surprise, she hung up and Officer Moseley wondered if she had made a serious error. But finally, “Karen” contacted her again, this time with her boyfriend, Jackson, and said the sandwich shop shooter was a former roommate, James Robinson. They were at a phone booth and wanted to talk.

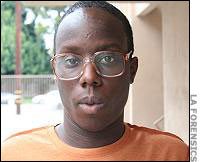

They told detectives about how Robinson, who had lived with them for a few weeks, had purchased a .380 on June 3. It had changed him, giving him an attitude of apparent invincibility heady stuff for a scrawny kid. Because he had debts and made little money at his grocery store job, he often talked about robbing the sandwich shop where he once had worked, but they had not believed he’d really do it. Still, he’d described a floor safe and the lack of surveillance equipment. He’d even said that if anyone was present that he knew when he did it, he’d have to shoot them, execution style to the back of the head. “They are going to die,” he reportedly had said, “because I need the money.” He specifically mentioned a tall, white employee with blond hair probably a reference to James White.

Robinson, 22, had been depressed over his financial state. His failure to pay his part of the phone bill had result in the phone being disconnected, so Jackson told him he had to find another place to live. On the night of June 29, around 11:00 P.M., Karen and Jackson heard Robinson put a clip in his gun. He left and Jackson saw that he’d taken his gun from its usual spot. Robinson came back, but quickly left again and did not return until 3:00 that morning. Directly after the incident, he had a bundle of cash and had rented an apartment, moving his stuff out. He’d also asked them rather excitedly if they had heard about the robbery and told them it was in the papers. They thought he was acting strangely.

Thus, only nine days from the time of the robbery, the detectives closed in on their first good suspect.

Richardson and Moseley set about corroborating the story so they could get evidence for an arrest warrant. The first item they acquired was proof from a dealer about Robinson’s purchase of a .380.

Around this time, they received another call from a man who currently worked with Robinson at a grocery store. They had both served in the Marines, he said, although Robinson had only lasted a few months, and Robinson had recently confessed to him that he had committed the sandwich shop murders in retaliation for a false accusation months before; he had seemed quite excited about it. He mentioned that a friend had been with him and described exactly how the crime had gone down. The caller provided this rendition of what Robinson had described about the incident:

Supposedly when Robinson walked in, one of the young men recognized him from a store where both had previously worked, and so he knew he’d have to shoot them both. So he’d pulled out the gun and made them open the cash register and safe. He then shot the tall kid, while the other tried to run. He caught him and shot him, but the gun didn’t have enough killing power,” so he’d had to shoot him again. He forgot to grab the cartridges before he fled out the back door. He added that the employee who had opened the safe was the one who had squealed on him the year before about the missing money. Both victims, he said, had pleaded for their lives.

The narrative didn’t quite match the facts, but it was close enough. Then a buddy of Robinson’s told the police that Robinson had bragged to him about the sandwich shop slayings. It was he who had urged Jackson to tell the police.

With four solid witnesses, the detectives got a warrant and went to where Robinson lived. He was there and willingly went to the station in custody while Richardson and Moseley searched his barren apartment. There they found a stainless steel .380 sitting in plain sight on a shelf over the television.

Robinson’s demeanor upon his arrest was also revealing. “He wasn’t sullen,” said Moseley. “He wasn’t excited. He wasn’t mad. He wasn’t angry. I mean, there should be some reaction from an innocent person, but he was void of emotion.”

But Robinson was not about to admit to anything.

On June 11, the LA Times announced that a former employee of the sandwich shop, James Robinson, had been arrested in the double homicide. Among the factors pointing to his guilt was that he had used a wad of cash to rent a Northridge apartment less than a day after the shooting. He’d pulled it from his fanny pack to pay the landlady but she told him to get a money order. She offered this information to the police.

Robinson had once worked at the shop but lost his job there in October, after only a few months, on suspicion that he had stolen $200. Before that, he’d been a student at California State University Northridge but had failed to pay his dorm and tuition fees with the financial aid he’d received, so he’d stopped attending. The paper went on to say that he was being held for arraignment in San Fernando Municipal Court.

Those who had worked with Robinson were surprised that he would have perpetrated such a horrendous crime. He always had seemed upbeat, cooperative, and friendly. In addition, he went to church and had even sung for a while in the choir.

James White had been hired after Robinson left, so it was unclear whether he had known the suspect, although his family said the two young men had briefly worked together at another place. Other sandwich shop employees said they had seen Robinson come into the shop several times after his termination.

At the time of his arrest, Robinson worked as a meat wrapper at a grocery store in Canoga Park. Even before the tip, the police were aware that he had a record for a minor infraction. He’d also been plagued by collection agencies after him for unpaid debts.

At the police station, Robinson waived his Miranda rights and agreed to talk, immediately denying he had killed anyone. He provided an alibi and said he’d been without his gun that evening because he could not find it in its usual place. He suspected his roommate had taken it the very person who had turned him in.

There were enough ambiguities from the scene to allow for this possibility. Then, when the eyewitness could not identify the shooter she had seen from a six-pack of photos, detectives knew they might face some problems, including reasonable doubt, but a specific piece of evidence would prove who was telling the truth.

With a warrant, SID collected the .380 semiautomatic pistol from the apartment that Robinson had just rented. They also collected clothing from Robinson’s room that resembled that described by the eyewitness. In addition, the police had received permission from Robinson to search a storage locker where he kept other belongings, and from there SID took several pairs of shoes to compare against the shoeprint from the store’s counter.

His pistol was rushed to the SID Firearms Analysis Unit, and the shoes went to the impression evidence section. Criminalist Daniel Rubin test-fired the pistol with sample ammunition to stamp the gun’s signature on the casings, and then compared them with those picked up at the crime scene.

“It we have a suspect firearm,” he said, “we can determine if those bullets were fired from that particular firearm to the exclusion of any other firearm, as well as with fired cartridge cases.”

He was aware that when two objects contact each other – depending on the surfaces of the objects, the relative hardness, the type of motion, and the pressure involved – the harder object (the tool) will leave a mark on the softer object. “In the case of a bullet being fired through a firearm, as it travels down the barrel, the inside surface of the barrel acts as a tool and that will leave a tool mark on the bearing surfaces of the bullet. With a cartridge case, when the cartridge is fired in the firearm, a tremendous amount of pressure is generated inside the chamber, causing the cartridge case to push very hard against the various surfaces of the firearm. That will leave a mark on the cartridge case from parts of the firearm.”

Rubin was able to prove, with a microscopic side-by-side comparison, that the same gun had fired the three bullets removed from the victims, and that it had been Robinson’s gun. But he could not prove who had shot it.

Unfortunately, none of the shoes matched the printed lifted from the shop’s counter. This did not exonerate Robinson he could have tossed the shoes away but the failure to match the impression did mean that SID could not definitively use this piece of evidence to place Robinson at the crime scene. They still had one item left: the fingerprints. After a comparison, it turned out that Robinson, not his roommate, had picked up the turkey and bacon sandwich.

When Robinson learned that the plastic bag implicated him, he quickly changed his story. He had been in the shop, he admitted, and had picked up the bag in the alley, but he hadn’t shot anyone. He had arrived after the victims were already dead, he claimed, and he’d seen Jackson’s gray Mustang drive away from the shop. Just before the shooting, he said, he’d been with a friend. When detectives checked his alibi against store records, they found that Robinson had had sufficient time to get from this person’s apartment, only a few blocks away, to the shop to commit the crime.

Nevertheless, it was clear that Robinson had an answer for everything. However, the DA’s office believed they had enough to take him to trial and to even surprise him. His slippery lies were no match for the evidence, and they could prove it.

“If it wasn’t for SID being able to match up our evidence that we recovered at the scene and by examining the gun, ” said Detective Richardson, “and even to the sketch artist, I have doubts that we would have been able to really pinpoint James Robinson for the murders.”

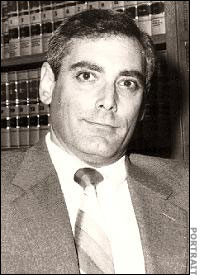

The trial began in April 1993.

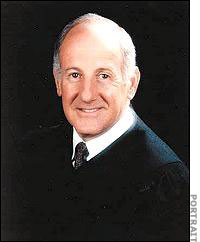

The case was argued before Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Ronald Coen. The prosecutor, Deputy District Attorney Kenneth Barshop, opened by laying out the case: he argued that the defendant had decided to rob the sandwich shop and execute the young men inside, because “dead men tell no tales.” Robinson was in desperate need of money and had become obsessed with guns. He had purchased a handgun and taken up target shooting, becoming enamored with the power it brought him. He had discussed robbing the store on several occasions prior to the shooting, knew about the safe from prior employment, knew there was no surveillance camera, had been dismissed for suspicion of theft, and was heard by roommates loading and preparing his gun before he left the apartment that night. He returned with a lot of cash, whereas he’d had none just hours before, and had even rented an apartment twelve hours after the robbery. He also bragged to a co-worker and another companion that he had committed the double homicide. His attitude was hardly one of remorse. In addition, physical evidence placed him at the scene and his gun was the weapon used. He had also lied several times in his statements to police.

Robinson’s attorney, Bruce Hill, declined to make an opening statement.

The eyewitness to the robbery and the customer who found the bodies testified first. By this time, Rebecca had identified Robinson as similar in height and build to the man she had seen, although he now wore glasses and she had not seen any on his face that night. He was also thinner than she recalled, but several acquaintances said he had lost weight.

Then Karen and Jackson testified about Robinson’s numerous pre-incident comments about robbing the shop. On the night they told him he would have to leave, they heard him load his gun and then the incident occurred.

Detective Moseley testified that they had compiled a murder book of 1,200 pages on the incident. Hill attempted to get her to say that another witness, in support of Robinson’s account, had described a gray Mustang in the area at the time, but she claimed to have no recollection of such a person. Hill offered no proof that such a witness even existed.

SID’s latent print examiner testified to the findings from the store and the plastic bag. He described the fuming method of preserving fingerprints on the plastic bag, and then showed the jury how Robinson had grabbed the bag twice: the two clear prints were slightly overlapping. Thus, when he said he had picked up the bag only once before dropping it again in the alley, he was clearly lying.

During the two-week trial, Robinson’s attorney, Bruce Hill, adopted several strategies. He put Robinson’s mother on the stand, as well as a dozen other people who knew him from his church. They all testified that he was a gentle, respectful person who was taking classes to improve himself, and not a killer. Hill also had Robinson, then 24, testify, and he had quite a story to tell. He might have been caught in a lie but he still knew how to twist the truth. And he was desperate. He knew the DA wanted the death penalty.

Robinson had heard that the physical evidence pretty much undermined his story, but he continued to claim that the two men were already dead when he arrived at the shop on the night of the shooting. According to the trial record, as stated in CA v. Robinson, Robinson gave the following account (often tearfully):

His former roommate, Jackson, was the one who had raised the issue of robbing the sandwich shop. Allegedly, he had asked Robinson to tell him about the receipts and the exit out the back. Robinson had tried to dissuade him, but Jackson had told Robinson to come meet him that night at the store. Then Robinson could not find his gun in its usual spot. He went to see a friend, which made him late for his appointment with Jackson. As he arrived at the sandwich shop, he discovered two men lying on the floor and the cash register and safe emptied. The security bar had been removed from the back door and as he opened it, he saw a car consistent with Jackson’s right down to a broken taillight drive away. Robinson picked up the discarded sandwich and dropped it again. He figured Jackson had used his gun to carry out the robbery and kill the young men, then set him up to take the heat. The following day, because of problems with Jackson and his girlfriend, Robinson had moved out.

So that’s why his fingerprints were on the bag and his gun matched the spent casings. In his favor was that, initially, the lone eyewitness had been unable to identify him from a photo line-up. She also said he had not been wearing glasses, and everyone knew he could not see well without them. Why would he have risked pulling off such a crime without glasses on?

On cross-examination, Barshop reminded Robinson that he had repeatedly told the police that he did not enter the sandwich shop when the crimes were committed. He admitted that he had lied then and had also faked his tears. When asked what he made of the fact that so many witnesses contradicted him, he said they had all lied or had not remembered things correctly. And what about those who claimed he had confessed to the crime? They, too, had supposedly lied.

But Barshop had effectively shown that Robinson himself could lie easily and turn on the tears when needed. Robinson was not a credible witness.

Robinson might have believed that with his accounting of the facts he could at least cause a hung jury or perhaps win the jurors’ sympathy and fend off the death penalty. They would see for themselves he was not a heartless executioner. In fact, some reporters described him as “dorky,” because he was scrawny, wore large glasses, and seemed pathetic. Yet the jury had also heard testimony from unrelated witnesses about Robinson’s enthusiastic bragging after the fact. They also had heard about fingerprint evidence from the plastic sandwich bag about which Robinson had also lied.

Some trial watchers thought the decision was obvious but others weren’t so sure.

As the jury deliberated over the course of three days, then had their verdict sealed for another three because the judge had a prior commitment, relatives of James White and Brian Berry spoke with the press. Brian’s father believed the death penalty would be appropriate, as did James’s mother, who nevertheless said it would be only a “hollow victory.” Both parents expressed how difficult it was to wait for the verdict.

On May 3, the jury’s decision was announced: Robinson was guilty of two counts of first-degree murder and one count of second-degree robbery, with special circumstances of multiple murder and robbery-murder. He was thus eligible for the death penalty. This jury would now go back and deliberate about the appropriate punishment.

Hill said that he believed the jury had given the evidence due consideration but he found it difficult that anyone would believe his client had committed the slayings. “I have to reconcile the James Robinson that I have gotten to know…is the James Robinson the jury has found guilty.”

Barshop, on the other hand, thought Robinson was a very good liar who could cry on cue. “He always had an explanation for everything.” While he was pleased with the verdict, he knew better than to celebrate too soon. Juries were never predictable.

The jury was unable to come to a decision about whether Robinson should get the death penalty, so it deadlocked. Judge Coen declared a mistrial and determined the need to empanel a second jury for the sentencing phase. He set a hearing date of June 11 for Barshop to state his intention of proceeding to a retrial. It was not an easy decision to make. Essentially, Barshop would have to retry the entire case in front of the new jury. In the alternative, Robinson would automatically receive life without the possibility of parole. Barshop knew that the families were counting on him to get the most exacting penalty possible.

He was depressed over the prospect of putting the families through this process again and delaying justice. “I’m very disappointed,” he said to reporters. “I thought death was the appropriate decision.” He learned that several jurors had decided that while they agreed with the death penalty, which made them eligible to sit on this jury, they could not actually make that decision about someone. Another juror said if he’d seen a videotape of the murder, he would have voted for death, but without that kind of proof, he couldn’t. Some jurors even had lingering doubts about Robinson’s guilt, which seemed surprising in light of the physical evidence. Still, he did not fit the stereotype of a vicious killer who was a danger to society and he had no criminal background.

Barshop decided to go for it. In 1994, he ran the same trial all over again to convince the penalty phase jury that Robinson deserved death. He hammered home how callous, arrogant, and vicious Robinson had been toward the two boys on the night of the robbery. He described again how James White had been on his knees, probably begging for his life after having witnessed his best friend shot in the face, and the convicted defendant had shot him straight through the head from above.

Robinson once again took the stand to claim he had not shot the two men; he’d merely been in the store.

The jury heard a great deal of testimony about the impact of the murders on friends and family some 37 trial pages worth of material. This trial was only slightly shorter than the original one had been. But it had a different outcome.

On June 18, taking less than a day, the second jury decided on two death sentences for the defendant. He showed no reaction, just as he’d stayed calm in the face of heated words from Brian Berry’s mother and sister.

At the trial’s conclusion, Robinson was transported to San Quentin, where he set about preparing his appeal.

Robinson received a court-appointed appellate lawyer, Susan Marr, to argue the merits of his complaints about the second trial. He objected to the sentence on several grounds. In his appeal he listed issues with the jury selection, the jury instructions, and the admission of an excessive amount of victim-impact testimony in the form of lengthy narratives. Some of the victims’ relatives had described how they had imagined the victims’ final moments, based on the medical examiner’s report. Robinson claimed this unfairly prejudiced the jury against him.

In 2005, the California Supreme Court disagreed with every argument he made, except the one about victim impact testimony, and upheld the death penalty. They did not address the merits of his claim about unfair jury prejudice.

“Strong evidence linked defendant to the crimes,” wrote Chief Justice Ronald M. George for the court, including Robinson’s prior employment at the shop, his financial distress, his reference to robbing the shop before it was done, and the match of the fingerprints and the bullets that killed the victims. He also had a lot of cash the day after the crimes, when he claimed he had none just prior. “We have not found any error in the penalty phase of the proceedings. The defendant received a fair trial.”

Another issue involved the medical examiner’s testimony. Based on the bullet trajectory through James White’s skull, Dr. Rogers had offered three different positions from which Robinson could have shot the boy. One was from the counter, which was excluded by the eyewitness testimony, one was from lying on the floor, which seemed awkward and thus unlikely, and one was from a standing position as the victim knelt on the floor. This one seemed most likely to him, given the fact that the victim was several inches taller than Robinson and the trajectory was at a downward angle. Robinson had objected to the image that the boy was praying or pleading on his knees, but the justices found that the Medical Examiner was within a professional context to form and state such an opinion to the court. Thus, Robinson’s protest was dismissed.

The court left open the possibility of a challenge on the basis of victim impact testimony, so it might be found during a federal appeal to have been excessive. However, the fact that Robinson’s attorney had not objected to any of it at the time will be a factor in the court’s consideration. Perhaps, then he can argue that he had had ineffective counsel.

For SID, this case affirmed the importance of careful processing, because only one of the many items of evidence had been able to definitively undermine Robinson’s story and pin the crimes directly on him.

* Some names have been changed to protect identities.

Berger, Leslie and Michael Connelly, “Killing No Longer a Stranger to Suburbs,” Los Angeles Times, December 15, 1991.

California v. James Robinson, Jr. Supreme Court Of California S040703, December 15, 2005.

Curtiss, Aaron “Childhood Friends Shot Dead at Northridge Sandwich Shop,” LA Times, July 1, 1991.

“Ex-worker Held in Restaurant Killings Crime,” LA Times, July 11, 1991.

“Formal Charges Filed in Sandwich Shop Deaths,” LA Times, July 12, 1991.

Moran, Julio, “Jury Told Defendant ‘Executed’ 2 in Northridge Sandwich Shop,” LA Times, April 13, 1993.

“Man, 24, Convicted in ’91 Shop Slayings,” LA Times, May 4, 1993.

“Penalty Phase Mistrial Declared in 2 Slayings,” LA Times, May 11, 1993.

Mrozek, Tom. “Student gets Death penalty for ’91 Slaying,” LA Times, May 20, 1994.

“Families of Slain Pair give Emotional Testimony,” LA Times, May 10, 1994.

Ofgang, Kenneth, “S.C. Upholds Ex-CSUN Student’s Death Sentence in 1991 Murders,” Metropolitan News-Enterprise, December 16, 2005.

O’Neill, Ann. “Man Receives 2 Death Sentences in Teen Slayings,” LA Times, June 18, 1994.

“San Fernando Valley Man Convicted of Killing Two Witnesses to Robbery,” LA Times, May 4, 1993.

“State Supreme Court Upholds Death Sentence for Subway Killer,” Associated Press, December 15, 2005.

“Trial Ordered in Sandwich Shop Deaths,” LA Times, January 15, 1992.

Interviews with investigators, forensic scientists, and crime scene personnel.