Death in Miniature — First Encounter — Crime Library

While on business at the Medical Examiner’s Office at the Baltimore city morgue, I happened to spot a series of tiny constructions sitting on shelves behind plastic. Curious, I took a closer look. They were dollhouses, but upon peeking inside I saw blood-splashed walls and tiny dolls lying face-up on kitchen floors, huddled under blankets, sprawled in bathtubs, or hanging from nooses. It was entirely incongruous: one does not expect to find dollhouses in the ME’s office, nor bloody corpses inside dollhouses. But there they were. And nearby was a guestbook for people to make comments.

Gruesome as it was to look at these pint-sized “corpses” stabbed and brutalized (people with bizarre fantasies do such things), it was also quite fascinating. It’s true that dolls are usually associated with children, to help them rehearse certain behaviors as well as be entertained, but for some people dolls also serve as fetish pieces and can even be transformed into frightening monsters. Their staring eyes can arouse considerable fear and aversion, and at least one serial killer became so fixated on artificial eyes that he cut real eyes from his victims. So these tiny “corpses,” both cute and obscene as they lay perfectly still in their detailed dioramas, evoked conflicting feelings.

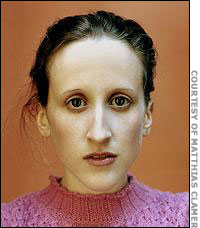

I asked about the models and learned that they’d been constructed during the 1940s to teach inexperienced police officers about different types of death scenes, and to encourage them to use careful observation to spot “indirect” evidence for crime reconstruction. I also learned about Frances Glessner Lee, the remarkable woman behind the project, who made each doll by hand — and who decided how each one would “die.” I thought at the time that there should be a book on these creations, and even as it crossed my mind, someone was already on it: a photographer, Corinne May Botz. She, too, had encountered these scenarios at the ME’s office and, haunted by them, wanted to create a legacy. She signed the guestbook and then came back for more.

While her publication, The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, is certainly the definitive account, there are other sources of information as well about Ms. Lee, notably an article written when she was alive, a 2004 piece in the New York Times, and a museum in Chicago based in the home where she grew up.

In addition, a new exhibition of forensic science, mounted by the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health, includes Frances Glessner Lee as a key contributor to its history. Her obsession with crime and her determination to provide instruction for investigators, supported by her wealth, made her a unique individual indeed. It was she who named this series of 19 scenarios “The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death,” so let’s first find out who she was.

Mrs. Frances Glessner Lee was known by family, friends and servants to be domineering and exacting, a perfectionist in everything she did (she even numbered the bottoms of vases in her home, says Botz, to ensure they were always on shelves with corresponding numbers). Yet she was also full of good humor, especially around police officers, many of whom sent her cards on Mother’s Day. In a 1949 article for the Coronet, George Oswald described her thus: “A queenly looking woman with the high, white coiffure and the tiny gold-rimmed eyeglasses is known as a passionate crusader for justice and a tireless lobbyist for reform.” It took her into her 50s to reach that status, but once she was there, she took full advantage.

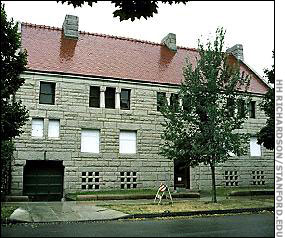

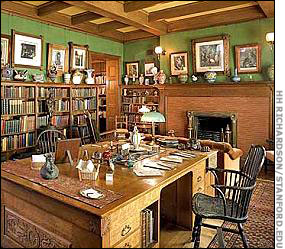

Born into a wealthy family on March 25, 1878, in Chicago (their fortune came from International Harvester), “Fanny” was raised in an austere, castle-like home (which many neighbors thought resembled a prison), designed by architect H. H. Richardson. She was protected, coddled, and exposed to many great minds, but tutored entirely in private. Hers was a life of privilege on Prairie Avenue, the wealthiest area of a booming city; she was surrounded by servants and the most exquisite handcrafted furnishings. Her father, industrialist John Jacob Glessner, even wrote a book about the house, now a museum, and lavished a great deal of attention on it. As Botz observes, “The very creation of the models [the Nutshells] can be viewed as a continuation or perversion of her parents’ obsession with their home.”

Young Frances, who developed a brilliant mind and an eye for detail, had high hopes of making a contribution one day, possibly in the field of medicine, but she was not allowed to attend a university. She had to watch as her older brother George went off to Harvard while she, like it or not, was doomed to the domestic scene. In later life, she considered that her existence had been lonely and devoid of human contact. Many who knew her, including her own son, thought she’d have been happier to have been born a male.

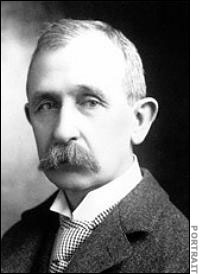

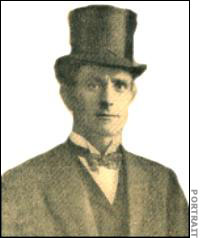

When she was 20, Frances married Blewett Lee, an attorney and law professor at Northwestern University. They had three children before the marriage failed after eight years — a social disgrace — and they eventually divorced. But Frances was soon caught up with a new direction. As a young wife and mother, she met a friend of her brother’s named George Burgess Magrath, who was just getting his MD from Harvard Medical School and aiming for a career in pathology. The Glessners had a thousand-acre summer home in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, called “the Rocks,” and during a vacation, Magrath came to visit. He talked about his interested in legal medicine, especially death investigation, but when Lee echoed his words to her father, Glessner made it clear that no member of his family would ever be caught up with such a sordid subject.

Apparently Glessner’s imperial dictates were no match for Magrath’s charismatic personality, so tales about medicine, investigation and death continued to fire Lee’s imagination. In fact, she followed Magrath’s career and kept in touch with him until the day he died when she was 60. (Her father died only two years before that, in 1936.) And Magrath was to benefit greatly from her interest. In 1930, a year after her brother died, Frances Glessner Lee began her own career in legal medicine, albeit indirectly. By then she was 52.

Magrath, who became the chief medical examiner for Suffolk County (Boston), had regaled Lee for years with his investigative tales and he often confided to her the need for better training for death investigators, especially because coroners, who managed death scenes in most states, were not required to have medical degrees. He thought it was important that medicine be included in their backgrounds, because to make accurate assessments they had to be familiar with the nuances of wounds and the different types of poisonings.

In fact, demand to switch from the British coroner system to a medical examiner system had begun in America before the Civil War. James Mohr writes about it in Doctors and the Law, pinpointing the strongest movement among physicians in Massachusetts and New York. They regarded the coroner system as corrupt and backwards, and after several financial scandals in Boston involving coroners, reform became a real concern. Thus, on July 1, 1877, Massachusetts became the first state to replace coroners with medical examiners. Two were appointed in Suffolk County to conduct the state’s autopsies, though they were granted limited powers.

A few other jurisdictions followed suit, but reform was by no means nationwide, and support for better medico-legal education was weak. A Medico-Legal Society formed in Massachusetts to advance the science, and a few cities emulated it, but the groups were splintered and largely inactive, so it was left for passionate physicians in the twentieth century to pick up the torch. Magrath was among them. (Even today, many states still have a coroner system. According to a report by Hanzlick and Combs in 1998, medical examiner systems serve about half of the U.S. population.)

Magrath undertook to teach Lee about legal medicine, for which she was deeply grateful. At the time, there was little information, so together they found whatever sources they could. Lee was agitated about crimes that went unsolved or unpunished, and she knew that better education might improve the situation. Yet her interest derived from something else as well. A fan of Sherlock Holmes stories, she was also fascinated by the way the circumstances of a crime might point to a solution, but then a clue might turn up at the autopsy or during the investigation that would indicate an entirely different scenario. She enjoyed the surprise factor.

With her usual industry, Lee set about to become an expert in the field and was eventually considered sufficiently knowledgeable to be viewed as an authoritative consultant. She was convinced that this was her calling, and her chance to make the contribution about which she had dreamed since childhood was not long away.

At one point during the late 1920s, Oswald writes, Lee became ill and spent a great deal of time in Boston recuperating. Magrath visited her each evening, entertaining her with more stories about his work. Each time he left she could hardly wait for his return. As they discussed the state of his profession, he admitted some apprehension that so few people were nurturing medical investigation that it ran the risk of losing ground.

Lee wanted to know what she could do to ensure its future. That question was the turning point. Magrath was well aware of her wealth, having visited the Rocks many times, so he apparently told her, “Make it possible for Harvard to teach legal medicine, and spread its use.”

Lee took up the cause of replacing coroners with medically versed professionals. At the Rocks, she created a home for herself not far from Boston, and from there, she could keep track of what happened at Harvard. Despite the way people viewed her as an eccentric women with too much time on her hands, she took her mission quite seriously.

In 1931 Lee helped to establish a department at Harvard for teaching legal medicine, as she herself paid the salary of its first professor. In Magrath’s name in 1934, she donated a library of more than 1,000 books and manuscripts that she had collected from around the world many of them rare. She also endowed the department with a sizable grant, and Magrath became its first chair. With Lee’s support, the Department of Legal Medicine trained students to become medical examiners, which involved seminars and conferences devoted to refining the discipline. Botz indicates that, as a result of this impressive and prestigious program, seven states eventually changed from a coroner system to a medical examiner system.

Oswald summarizes two cases that directly benefited from Lee’s support of the program. In the first one, a set of skeletonized remains was found on a Boston-area beach. Ordinarily, there would have been little hope of making an identification, but forensic science had improved. A team took bone measurements and X-rays, determining that the remains were of a five-foot-eight female, age 18-21. A set of tiny bones found with these remains indicated that the victim had been killed while pregnant. Other sciences got in the act, with forensic botany and entomology pinpointing the approximate time of her death as a two-week period at the end of May. Detectives looked at lists of missing woman and identified a likely match with a young woman missing since May from a nearby town. The man with whom she had been involved was questioned, and he confessed to having murdered his girlfriend and dumping her on the beach.

In the second case, an elderly couple was shot in their home. The woman was dead but the man, wounded in the head, identified his stepson as the likely culprit. In fact, the gun used had belonged to the stepson, who had no alibi and who admitted they had quarreled. Yet rather than rush to judgment, as some police officers might have done, the detectives involved had been trained at the seminars to be observant and circumspect. They knew that things were not always as they seemed. As Oswald put it, they “looked for the kind of surprise clue which Mrs. Lee would provocatively put into her education.” An impression in the linoleum of the stepfather’s chair indicated that he might have fired the gun that had made the wound at the back of his head. The detectives questioned the old man again and he admitted that he had shot his wife and himself.

Many officers saw the value in being forced to think carefully about a crime scene, which gratified Magrath. According to Oswald, Magrath himself would be among those investigators in the early part of the twentieth century to be called “the American Sherlock Holmes.” But Magrath did not have long to enjoy the fruits of his collaboration with Lee. After developing the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard, he died in 1938.

Lee was heartbroken, but she continued to support Magrath’s vision. She was just picking up steam and was about to undertake her most innovative work.

In 1943, Frances Glessner Lee received an honorary appointment as a captain of the New Hampshire State Police, which made her the first woman to hold such a position, and in 1949 she was also the first woman to be invited to the initial meetings of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences. She attended the lectures during the second year of its existence. In addition, she became the first female invited to join the International Association for the Chiefs of Police.

Yet even as some officers counted her as their patron saint, she took ridicule for her plain style. She wore her hair clipped short and her dress tended to be black. Her routine was rigid, her manner abrupt, and she did not flinch from bullying to get a job done the way she wanted it. Since she enjoyed precision, it was natural that she would cultivate a scientific attitude. Those who valued her contribution got along with her quite well, and even counted it a privilege to have known her.

Lee had noticed, largely thanks to Magrath, that police officers often made mistakes when trying to determine whether a death was the result of an accident, a natural event, a suicide, or a homicide. Too often they simply missed clues. She thought that something concrete and practical should be done to mitigate this, and she envisioned a series of crime tableaux as teaching devices. They could be made to scale, she believed, and include all the items found in actual crime scenes. From her domestic upper class training, she knew just what to do: she would replicate crime scenes in miniature.

Lee’s first attempt to create a miniature was not, in fact, one of the Nutshells. Instead, according to Botz, it was a replica of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, a gift she made when she was 35 for her music-loving mother. Lee spent two months crafting ninety tiny musicians, all fully garbed and each with musical scores and a specific instrument. It was not uncommon during this era for women of means to make miniatures as a pastime, but Lee had been fully immersed in the project. Her sense of perfection paid off. Her mother was delighted. Then she tried another one, but this project took two years. This replica was also of musicians, but it was so minutely individualized that the four men on whom she had based it were astonished by the resemblance. Thus, Lee was fully prepared to take on the Nutshells Studies.

Her motto, according to the NIH site, as she had heard from a detective, was “convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.” To put herself fully into the project, she set aside the second floor of her four-story mansion at the Rocks for a workshop, filling one room entirely with miniature furniture from which she could select whatever she needed. To create each diorama, she blended several stories, sometimes going with police officers to crime scenes or the morgue, sometimes reading reports in the newspapers, sometimes interviewing witnesses, and sometimes utilizing fiction. She apparently even attended autopsies. She preferred enigmatic scenarios, where the answer was not obvious; One had to examine all the clues, including items that did not initially appear significant. Always changing the names, she kept real scenes confidential. At times, for her own delight, she included items or wallpaper patterns from her own household.

It wasn’t long before Lee had everything she needed to put together some grisly scenes. For her, these were not dollhouses or miniatures, but teaching tools.

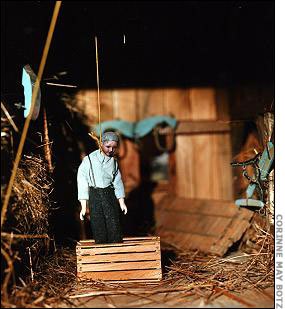

Lee spent an enormous amount of time on each diorama, collecting miniature furniture from all over the world on her travels, and making many of the items herself. (Botz writes that she once even corrected a doll furniture company for getting the scale slightly wrong.) Sometimes Lee purchased ready-made furnishing of high quality and other times she commissioned a carpenter to make what she wanted. The little buildings, from cabins to three-room apartments to garages, were also fashioned from her design, built on a scale of one inch to one foot. Carpenter Ralph Mosher worked with her for eight years, and when he died his son, Alton, took over. They lived at the Rocks, in a house that Lee provided, and managed to turn out an average of three Nutshells per year, although some years were slower than others. Each one cost about the same amount as an average house at that time.

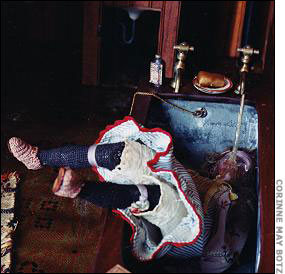

And it was no surprise, for the amount of detail Lee demanded involved many hours of painstaking work. She made each doll by hand, as Botz describes it: “She began with loose bisque heads, upper torsos, hands meant for German dolls, and with carved wooden feet and legs. She attached these loose body parts to a cloth body stuffed with cotton and BB gun pellets for weight and flexibility. She carefully painted the faces in colors and tones that indicated how long the person had been dead.” Lee added sweaters and socks that she’d knitted with great difficulty on straight pins, and items of clothing that were meticulously hand-sewn.

Once the dolls were ready, Lee would decide just how each should “die,” and proceed to stick knives in them, paint signs of decomposition on their pale skin, or tie nooses around their necks and hang them up. By far, the majority of victims were female, and some were children even a baby. All of the dolls were white, and many lived in economically deprived circumstances, a long way from Lee’s safe and privileged world. From her detached distance, she must have enjoyed getting everything just right.

In the rooms or yards, she placed tiny cigarettes she’d rolled, clothespins she’d whittled, books or newspapers she had prepared, and prescription bottle labels she had printed by hand. A trash bag would contain opened cans and boxes, a sink half-peeled potatoes, and an ashtray too many stubbed-out butts. Sometimes Lee used items from charm bracelets or Cracker Jacks boxes, and a “mouse” caught in a trap was actually a pussy willow bud. There seemed no end to her innovation.

Her carpenters, too, were instructed to make doors and windows that actually worked, with shades that rolled up and locks with miniature keys that opened them. In some rooms, Lee placed scaled-down miniatures that the tiny children might play with miniatures inside miniatures. And there were always subtle clues an open beer bottle, bullet casings, or a pile of letters that would become instrumental in the seminars. Lee labeled the dioramas with titles like “Unpapered Bedroom,” “Kitchen” or “Burned Cabin,” and each of the 19 scenarios told a complicated story.

While Lee generally based the dioramas on a combination of items, one can only wonder how much sensational news reports at the time had influenced her. Botz mentions the famous “Brides in the Bath” case from the early 1900s in England as a potential inspiration, at least in part, for the Nutshell labeled, “Dark Bathroom.” She indicates from her research that Lee was certainly familiar with it.

In Highgate, Margaret Lloyd had died in her bath. It seemed an unusual albeit accidental drowning, and the case might have been closed had not a relative of a victim of a similar drowning spotted Lloyd’s obituary and gone to the police. That victim’s husband had been one George Joseph Smith, who also turned out to be the husband of the unfortunate Lloyd, under an assumed name. Detectives then turned up the fact that Smith had been married three times, and all three wives had died mysteriously in their baths. Coincidence seemed unlikely, though the police were hard-pressed to explain how a person could be drowned in a bathtub without evidence of a struggle. Truthfully, there had been no mark of violence on any of the three bodies.

Pathologist Bernard Spilsbury experimented with young women in bathing outfits who agreed to sit in water-filled bathtubs and allow him and a detective to try to drown them. After repeated failures, it seemed to investigators impossible to make a person drown in this context and they were about to let Smith go. But then they figured it out: Smith had killed each woman by grabbing her by the feet and pulling her torso and head into the water. The quick action and rush of water had made her helpless. When the team tried this with the experiment participants, one of them went instantly unconscious. It was evidence enough to believe that Smith had figured out what to do to kill these women without much effort, and had enriched himself on their money or life insurance. He was convicted, and in 1915, executed.

The scenario that Lee depicted was somewhat different, but it involved a woman lying face up in her tub, with the water running on her face. Rather than being the victim of outright murder, however, she might have been the accidental victim of friends attempting to revive her after some hard partying. Botz suggests an addition influence from a case that Magrath had investigated in 1927 of a woman found dead outside, lying in a strangely posed position. This murder was pinned on Frederick Knowlton, who had left the body in a sitting position for a while before dumping it. He, too, was subsequently executed. Neither case is quite like that in “Dark Bathroom,” but both offer elements suggestive of the scenario. It’s rather fun to try to link crimes from Lee’s day to some of her Nutshells.

In “Burned Cabin,” the model shows a meticulously built cabin after a destructive fire had incinerated it. In this 1943 “incident,” Lee’s description indicates that two men had resided there, an uncle and nephew; the uncle was dead in the bed and the nephew gave a statement to the police that he’d woken up and run from the burning building. The fact that he was fully dressed made his story suspicious.

To achieve a sense of authenticity, this model had been built and then burned with a blowtorch to replicate an actual crime. While no one mentions it, Lee was likely aware of the reputation of Edward O. Heinrich, a criminology professor from the University of California at Berkley, who was renowned for his uncanny ability to read seemingly invisible clues. He was often called into cases on the West Coast that defied solution, and one involved a burned building that turned out to be other than what it seemed.

In 1925, an incinerated set of human remains was found in the laboratory of Charles Schwartz after an explosion, and Schwartz had turned up missing. Heinrich used an X-ray to indicate that the victim had been bludgeoned to death rather than killed by the explosion, so he suggested it was a staged scene with an unknown victim. However, the corpse was missing a molar that matched dental records for Schwartz, so the police were ready to conclude that the corpse was Schwartz’s. But Heinrich was not deterred. He asked for photographs of Schwartz, but the man’s widow reported that someone had entered her home and stolen them all. Still, she had left one at a photo studio, so she retrieved it and delivered it to Heinrich. He compared it to the corpse and noted that the single intact earlobe was the wrong shape. In addition, the missing molar from the jaw had been forcibly yanked out, and quite recently. The eyes, too, had been gouged out, and chemical tests proved that the fingertips had been burned with acid.

The police re-opened the case and learned that Schwartz was a long-time confidence man, living off his wife’s money and falsely posing as something he was not. He had befriended a missionary who resembled him, killed the man, put his body in the laboratory that he then exploded, pulled out the tooth, and fled. Investigators tried to lure him out with rumors of a large life insurance settlement, but rather than be caught he shot himself.

In the Lee scenario, it could be that the nephew killed the uncle, set the fire and tried to stage the death to appear the result of the fire. But it would take a shrewd and observant investigator to look for the right clues. That’s just what she had in mind, and to make sure that more officers were able to do this, she supported formal seminars for training.

Oswald writes that, by 1949, some 2,000 doctors and 4,000 lawyers had been educated at the Harvard Department of Legal Medicine. In addition, there had been “several thousand state troopers, city detectives, coroners and district attorneys of all states of the Union, plus insurance men and newspaper reporters” who had attended the week-long seminars put on twice a year. Lee, whose money paid for these educational sessions, would be the only woman in attendance, and once the Nutshells became part of the seminars, one day of each week was set aside to showcase them, with the new ones added each year. They were placed in a temperature-controlled room and officers were given a limited amount of time to take notes of what they observed and report back to the others. The point was not to “solve” the crimes but to notice the important evidence that would make a difference in the investigative decisions.

In a written instruction, Lee urged those preparing to observe a scene to imagine themselves as less than half a foot tall. She also advised that they adopt a geometric search pattern, such as a clockwise spiral, to accomplish a methodical examination. They must look at the entire scene, searching for clues that might not be obvious, such as a bullet caught in a ceiling, a pattern of blood that undermined an obvious theory, a weapon in an odd position, or evidence of behaviors that would point away from a determination of suicide.

Lee would pen a few spare descriptions to assist, such as the one Oswald reports about a crime that “occurred” on April 12, 1944. “Mrs. Fred Barnes, housewife, dead.” Lee would provide a bit of background and assure observers that all the clues were evident. They were then on their own to attempt a reconstruction.

In the scene, she had included items that weren’t clear at a glance, such as an item under the bed or a smudge of lipstick on a pillow slip, but when these were revealed, they would help to alert detectives and police officers to the need to look for subtle clues. What appears to be a suicide, for example, may change when a key item is noted a fresh-baked cake, a load of freshly-laundered clothing, an ice cube tray beside the body (what woman does all that when she plans to end her life?). Other scenarios included a bound prostitute with a sliced throat, a man hanging in a wooden cabin, a boy dead on a street, and an apparent murder/suicide. Detectives were forced to look at these models as carefully as they would an actual crime scene.

As part of the seminar, Lee always put on a magnificent dinner at the Ritz Carlton, on expensive china that she had purchased, which was used exclusively for this occasion. Those in attendance often had never experienced such luxury and they came to appreciate this woman to whom many referred as “Mother.”

Oswald writes that a state trooper told Lee that the Nutshell Studies had helped him to learn how to handle difficult cases. If not for the challenge she had put to him, and the surprises that he’d experienced upon learning about clues he had missed, he might not have been as careful as he’d become. For her, such reports made the endeavor and the $60,000-plus that she had spent on the projects worthwhile.

Once these seminars proved a success, others were organized in other states. On the anniversary of the first one in 1946, graduates came back together to form the Harvard Associates in Police Science (HAPS), and each graduate thereafter become a member. Lee assured them that she intended to be involved until the day she died.

When her eyesight failed, her doctors forbid her from working, so she had a radio installed in her room to listen to the police reports. But with the poor reception in the White Mountains, she was able to hear only the reports from the Virginia State Police. She wrote encouraging letters, and the chief invited her to Virginia. There she pleaded for support for medico-legal education, and reform soon followed. At that time Lee estimated that it would take her until about 1960 to bring the rest of the country into line with medical examiner systems. She died in 1962 without realizing her vision, but nevertheless left a lasting legacy.

The Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard closed in 1966, and thanks to a professor there, Dr. Russell Fisher, the Nutshells were moved to the Office of the Medical Examiner in Baltimore, MD. In 1992, a grant was offered so they could be restored.

Since it may be difficult or impossible for many interested parties to view them, one can do the next best thing, which is to view them in the book of photographs produced by Corinne May Botz.

Botz first describes how she learned about the Nutshell Studies when she was a student at the Maryland Institute College of Art. She was making a video about women who collected dollhouses, including a prosecutor who loved the houses but wanted no dolls. This woman directed Botz to the Baltimore ME’s Office, so she visited and soon found herself fascinated with the macabre creations. “I was blown away,” she said in an interview. “I was amazed. My visit happened to be on my birthday, and it brought together all these different interests of mine: I was interested in dollhouses and miniatures and crime, and I saw in the Studies an uncanny combination of sweetness and sinister. They’re these amazing little worlds that I immediately lost myself inside.”

In her book, she writes, “I was entranced by the details: the porcelain doll with a broken arm in the attic, the grains of sugar on the kitchen floor, the fallen book with a flying witch on the cover. I was also riveted by the miniature corpses.” She found it somewhat ironic that she was taking photographs of three-dimensional objects that had, themselves, been inspired by photographs of actual crime scenes. “My photographs simultaneously moved the models further from and closer to their source.”

Inevitably, Botz wanted to know more about the woman who had devised and created them. She interview a number of people, including Alton Mosher, Lee’s commissioned carpenter, who still had one of the few unfinished models. Botz also spoke with Lee’s daughter-in-law, Percy Lee, before the woman died, with descendants, and with police officers who had gone through the Harvard training seminars that involved the models. “I talked with Bill Baker, who’s now an editor of Harvard Associates in Police Science. He knew Frances Glessner Lee; she rode around with him to some of his cases, and he trained on the models. They still have the seminars for police officers and he’s quite active in that. He gave me names of some of the older officers who had gone through the seminars.”

It took seven years to do the interviews and research, take the 500-plus close-up photographs, and put together the book, but once it was done Botz provided a comprehensive, even definitive, portrait. To accomplish this, she went to the homes in which Lee had lived and sought clues about her in the meticulous dioramas. She even did a rubbing from Lee’s tombstone. Unsure about just how to tell Lee’s story, she settled for a fact-based narrative surrounded by the diorama photographs, which in themselves offer a great deal about what Frances Glessner Lee was like as a person. As Richard Woodward says in the introduction, “the idea that a mature woman had taken a fancy plaything for little girls and turned it into a grim, bloodstained teaching tool for grown men must have seemed distinctly odd.”

Asked for her impression of Frances Glessner Lee, now that all is said and done, Botz said, “I admire her efforts to improve crime investigation, and the fact that during that early period she advanced in a male-dominated field. From an individual standpoint, she’s very complex and fascinating. As I learned from her family, she was very difficult to get along with, and this is in part because she was a brilliant woman who lived most of her life according to what was expected of an upper class woman. Lee’s presence in the Nutshells has always been overwhelming for me. The Nutshells are over-determined objects that reveal Lee’s own personal experience of space and forensics.”

Botz was able to photograph all of the Nutshell Studies that Lee had completed, except for one. “One of the Nutshells was lost or destroyed. It was the best one for training purposes, actually. Lee had used it for teaching, because it was a study of two scenes, a ‘before’ and ‘after,’ and you had to figure out how the police had botched the case. It showed a model of a woman who killed her husband and she’s sweeping up evidence while the detective is standing there with his notebook in his hand.”

In general, Botz prefers the domestic scenes, particularly one called “Parsonage Parlor.” A young girl, “Dorothy Dennison,” lay dead on the floor. This crime was “reported” on Friday, August 23, 1946. As the story goes, Dorothy had gone out to purchase meat for dinner four days before, and while people saw her at the market, she did not return home. Her mother, Mrs. James Dennison, called the police late that afternoon and Detective Robert Peal responded. The police searched empty buildings in the area, and finally found the body, face up in the parsonage and seemingly posed. Temperatures in the mid-80s and high humidity readings had influenced the degree of decomposition, and there were bite marks evident on her chest and legs. A knife stuck out from the corpse’s left side, beneath the ribs. Except for the body, a hammer, a package of maggoty meat on a chair, and a lone lamp, everything in the room was perfectly paired. A church rector who resided in the house had been absent for several months, as indicated by a pile of tiny pieces of mail by the door. Clearly, the perpetrator realized the place was both furnished and devoid of potential witnesses. But the body’s condition does not square with the package of meat, which has been there longer.

“It’s one of the most violent scenes,” Botz says. “It’s a scene of innocence destroyed, and there are so many amazing symbols. She’s dressed in a white dress with red ballet slippers, a red belt, and red bow in her hair. There’s a picture of the Virgin Mary and child on the wall, and we read about her mother’s increasing panic in the police report. With all these symbols, it’s like an allegorical painting. This case touches me the most.”

The project of photographing the Nutshell Studies and learning about the woman who designed them had offered an unexpected dimension for Botz. “I first saw them on my twentieth birthday, and I kind of grew up in the process of taking the pictures and writing the book. During that time, I was in art school, where I learned a lot about photography and perspective, but a formative part of my education came from the unending hours I spent looking at the Nutshells. I learned a lot about methods of seeing for training detectives, and the psychic and cultural power an object can hold. It’s interesting because now when I photograph life-size interiors, people often mistake them for miniature.”

She has displayed the pictures in different galleries, from New York to Washington, D.C., but one of her favorite places was the Glessner Museum in Chicago, the home where Lee grew up. “We showed the photographs in what was Frances Glessner Lee’s former bedroom. It was an empty room, and in the room next to it they displayed objects that had belonged to Lee, like childhood toys. Everybody there had done research on her early life, and had read her mother’s journals. They were the most lively group people, and it was special because the exhibit brought everyone together in that space.”

But Lee is not the only one to see the potential for learning from such miniatures.

Popular Science recently featured another instructor who uses doll-size crime scenes. Tom Mauriello teaches criminalistics at the University of Maryland in College Park, not far from where the Nutshell studies can be viewed. He’s aware of them and was impressed enough to create scenarios of his own. Yet there’s a difference. The dolls and crime scene fixtures he offers students can be handled. In fact, he wants students to handle them and he even goes so far as to say that those who do will make better investigators than those who hang back. Curiosity is key.

For his purposes, Mauriello has created six scenarios, including a car locked inside a garage and a doll in bed with a gun. Students can figure out what occurred from clues planted around the scene. They can also use laboratory equipment to analyze unusual spots or substances, just like real investigators.

Yet Lee’s creations do not sit idle. The Harvard Associates in Police Science continue to use the models in its bi-annual teaching seminars. A few have been retired because they proved a bit too enigmatic, but the others are excellent resources. Still, they’re reserved for police officers.

While one of the Nutshell Studies is featured in the lobby of the ME’s office, the others can be viewed on the third floor, but interested parties must write for permission. They can address inquires to Dr. David Fowler, MD, Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, 111 Penn Street, Baltimore, MD 21201.

When Lee died, her friend, Erle Stanley Garner, author of the Perry Mason series, wrote in her obituary, “Captain Lee had a strong individuality, a unique, unforgettable character, was a fiercely competent fighter, and a practical idealist.” She certainly left us a most unique approach to crime education, and she clearly lived her childhood dream.

Botz, Corrine May. The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Deaths. Monacelli Press, 2004.

Doublet, Jennifer. “Existance Minimum/Maximum,” loudpapermag.com, Vol. 3, # 3.Glessner House Museum, Chicago, IL.

Field, Kenneth S. History of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, 1948-1998.

Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: American Society for Testing and Materials, 1996.

Kahn, Eve. “Murder Downsized,” The New York Times, October 7, 2004.

“Francis Glessner Lee,” Biographies, Visible Proofs, nlm.nih.gov, retrieved June 17, 2006.

Hanzlick, R. and D. Combs. “Medical Examiner and Coroner Systems: History and Trends,” ncbi.nlm.gov., retrieved June 23, 2006.

“In Cold Blood: The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death,” 2wice. 2004.

Maxwell, Douglas. “Oh, You Beautiful Doll,” New York Arts Magazine, May/June 2006.

Miller, Laura. “Frances Glessner Lee: Brief Life of a Forensic Miniaturist,” Harvard

Magazine, harvardmagazine.com, retrieved June 18, 2006.

Mohr, James C. Doctors and the Law. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

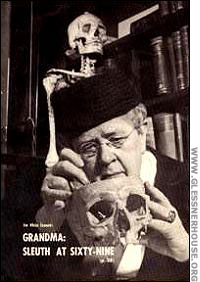

Oswald, George. “Grandma Knows her Murders,” Coronet (1949), reprinted on www.sameshield.com, ret., June 18, 2006.

Sachs, Jessica Snyder. “Welcome to the Dollhouses of Death,” Popular Science. 2005.

Sward, Jeffrey. “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained deaths.” jeffreysward.com, retrieved June 17, 2005.

Best Dioramas, Baltimore Living. Interview with Corinne May Botz, June 23, 2006.