Salem Witch trials — Parris — Crime Library

Parris

The Rev. Samuel Parris was worried that his daughter was going mad. Insanity had touched his family, but his daughter Betty was much too young for the madness that consumed his ancestors. She had always been a frail, delicate child, often in her sickbed, but never before had 9-year-old Betty shown the signs of mental illness that would eventually end in complete lunacy like the others in the Parris line. Recently, however, the poor girl was exhibiting signs that her mind was slowly deteriorating. There was no other explanation for Bettys absent-mindedness, her blank gaze, the forgetfulness and especially the insubordination.

Like many of the other Salem Village young women, Betty was spending a great deal of unsupervised time with the slave Tituba, but Parris had owned the half Carib Indian-half African woman and her husband, John, since he had arrived in Barbados years before and trusted them. He brought the slaves to Massachusetts Bay Colony when he answered the call for a minister at the new Salem Village church, and although Tituba was petulant and lazy, he had no qualms with her looking after his child and his niece, 11-year-old Abigail. He doubted that Tituba had been a bad influence on the girl.

Parris pushed the thought of Bettys deteriorating state of mind out of his head as he entered the Salem Village meeting house. There was no other place quite like Salem Village, he thought to himself. The place had a cantankerous reputation and some people said the atmosphere was like a bloodless feud. The village was divided by a political and economic schism into two camps, with Parris in the center.

Entering the cold meetinghouse Parris muttered under his breath as he looked around for firewood. The village was supposed to provide him with an allotment of firewood during the winter, but half the congregation had failed to supply their tithe. As a result, Parris was forced to keep the fire burning lower than he liked. The alternative was to gather firewood himself, but that would mean yielding a portion of his contract and he had no intention of backing down further.

marked (AP)

The acrimony started long before Parris had arrived from Barbados. In truth, it began before Parris was even born. Named for the holy city of Jerusalem, Salem town was founded in 1626 by English merchants who took advantage of the natural harbor and abundant fishing the area provided. As the Puritan movement in England grew and the Puritans became more oppressed, they immigrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony to build the City on a Hill that John Winthrop had promised. Situated not far from Boston, but not too close for the comfort of the Puritans, the town prospered. Indian raids notwithstanding, Salem was generally a pleasant place to live. A bit rough, perhaps, but the Puritans liked it that way. Their mission was to return the Church to the state it enjoyed when it had been founded by Jesus Christ, and worldly distractions like secular literature and entertainment could only serve to distract them from their goal. The Puritans did not celebrate even the pagan holidays of Christmas and Mardi Gras.

As Salem prospered, more families moved to the outskirts of town, into the area informally known as “Salem Farms.” The Farms was still under the jurisdiction of Salem Town and subject to the theocratic rule of the church there, but as time passed the division between the townspeople and the farmers grew. The farmers were expected to pay taxes to support the Salem Town church and they had to send men into town to stand watch leaving their own homesteads unprotected. Declarations, requests, petitions and letters flew back and forth between town and farms as the farmers sought to gain their independence and the townspeople refused to relinquish control.

Religious convenience also played a role in the developing feud, and that is where Samuel Parris entered the fray. With no church of their own, the residents of Salem Farms were expected to attend services twice weekly in the Salem Town Meeting House, a considerable distance for some. In the Puritan faith, and thus in the Massachusetts Bay theocracy, establishing a church was not as simple as erecting a building. A Puritan church was much more than just a house of worship. The church and its leaders dictated public policy, social mores, appointed civil servants and generally set the tone for the community. There was no separation of church and state in 17th century Massachusetts. The tithes assessed against the farmers were significant revenue sources for the Salem Town church and a request by the farmers to build a church of their own was not a matter to be treated lightly. The first request to build a church in the outskirts of Salem Town came in 1660 from a group of farmers who were full members of the Salem Town church. The request was met with silence; a second request met with denial, a third met with delay and subsequent requests were submitted to committees and endless debates.

However, in 1672 Salem Village, as the Farms had become known, was granted permission to assess a tax to build a meetinghouse and hire a minister. Church membership in Puritan society was extended only to a select few. Those who were not members of the church were considered the congregation, and they were “obliged to support the ministry with their material goods and to attend meetings at which God’s word was expounded, but the church itself, as an elite cadre of the community, met separately…to partake of the privileged rite of communion,” wrote historians Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum in Salem Possessed.

That first minister in Salem Village was the Rev. James Bayley who arrived in October 1672. An inexperienced pastor, Bayley was no match for the powerful forces already in place in Salem who opposed his ministry. When he came under attack from the opposition (for no less than omitting family prayers in his own household), anti-Bayley forces withheld their taxes until the poor man was nearly destitute.

Eventually, Bayley left Salem, fed up with the village, the town and the ministry in general. He eventually became a doctor in Roxbury, Massachusetts.

After Bayley came George Burroughs, but his stay in Salem was no less fractious than Bayley’s. Burroughs stayed two years in Salem and left amid controversy to take a parish in Maine. Deodat Larson, an unordained minister followed Burroughs. Again contention arose in the church and Larson’s bid to become an ordained minister failed. He left, and after a lengthy search and protracted negotiations, Samuel Parris agreed to leave sunny Barbados for Massachusetts Bay Colony and Salem Village.

It was a fateful decision that he did not enter into lightly. Parris knew he would be involved in battles as a course of his ministry. He expected no less, because living under the strict Puritan code of morality left little outlet for hostility and aggression. That, combined with the Puritan belief that each person was responsible for monitoring his neighbor’s piety, made conflict inevitable. What he did not expect was that he would have to do battle with the Devil. Moreover, he never would have dreamed that those living under his own roof would be the ones who brought Satan to Salem Village.

Like her master, Tituba was concerned about what was going on in the Parris household. She felt genuine affection for little Betty Parris and her cousin Abigail Williams, but not knowing that insanity was a Parris family curse, she was more afraid that her own actions had brought this affliction on Miss Betty. Life was difficult for Tituba in Massachusetts, especially in winter. She was born and raised in Barbados where it was so hot that even the plantation slaves were expected to rest much of the day so as not to exhaust themselves in the heat. But here in Massachusetts it was colder than she had ever imagined. Even in the summer it was chilly, as the virgin forest kept the sun from breaking through. Also, the cold meant there was no excuse not to do work.

in the Parris home

The Rev. Parris wasn’t a bad man in her opinion. In the privacy of her own shack he let her keep the white cloth, flowers and tin statues which represented her altar to Obatala, the creator of humanity and owner of the world in her Yoruba faith. He respected her ability to create salves out of native plants and the way she nursed young Betty when she fell ill. Most importantly, Parris was good about leaving her alone. She had assigned duties, but the minister was so busy with his parish that he seldom noticed if the floor was swept or the linens changed. Mrs. Parris was equally busy with the duties of the wife of a minister. The Puritans believed in looking in on their neighbors, not out of kindness, but more out of a half-hearted concern for their souls, and no one was more active in the community than Mrs. Parris. So running the household and managing the two girls and their friends fell to Tituba. She made the most of it. She spent hours telling the girls of the beautiful white beaches of Barbados and the sugar cane so sweet and plentiful. They listened enraptured as she told them of the witch doctors who could tell the future and heal the sick with incense and herbs. The girls asked so many questions about magic and witches and fortune-telling that she finally broke down and showed them how to break a fresh chicken egg from a white hen in just such a way that the egg white would be suspended in water and would serve as a crystal ball to reveal the future.

This was risky business, of course and all the girls knew it. It was a secret they kept from everyone outside their own small circle, for they knew if they were discovered the strict Puritan code would require a whipping, followed by hours of prayer and days of fasting. That made it all the more exciting for them, Tituba included. The secrecy lent truth to the tales Tituba wove. The clandestine meetings that took place in the parsonage while the reverend and his wife were out served as an outlet for these repressed young women who were going through the pains of puberty without any other ways to relieve the stress. Most of them lived in close quarters with extended families, often sharing beds with siblings. Privacy was anathema to Puritans, because in private, people sinned. Discussions about changes to their bodies and minds were uncommon, and many questions remained that could only be discussed in secret with friends.

Many of the girls, like Betty, felt the tug-of-war going on between their enjoyment of the chats with Tituba and the lessons they were learning at home and in church. The idea that they were flirting with the Devil and possibly gambling with their immortal souls was troubling to some and exciting to others, depending on their understanding of predestination. The Puritans believed God had decided their fate long before they were born, so whether or not they were to be saved was unrelated to their conduct on Earth. That did not provide an excuse to do whatever one pleased, of course, because God had handed down rules for living on Earth and to go against God’s will now would surely invite Divine retribution.

Abigail was more mischievous than her cousin, and she viewed the black magic and fortune telling as merely a game. While Abby didnt see any harm in it, Betty began to be plagued with guilt and fear over the shenanigans. Shy and submissive, Betty was not one to stop the voodoo and she was afraid to go to her father to confess. The conflict raged within her and it began to have physical effects. She was wan and weak, unable to eat, and she began to forget chores. Betty appeared to be off in a dream world at times, and when awakened would scream and being pressed for an explanation would give utterance to a meaningless babbling.

Bettys behavior was bound to point back at Tituba, the slave thought. After all, it was she who taught the girls about fortune telling and how to find the name of their future husbands by looking into the egg white. Tituba was the one who spun the yarns about voodoo and the spirits who inhabited the trees and rivers. She only half-believed them herself, but to the impressionable young ladies of Salem, such tales seemed not only possible, but also likely. After all, Ann Putnam the Younger was an expert in the Book of Revelations, thanks to her mother’s obsession with Doomsday, and Ann was unequivocal in her support of Tituba’s claims.

When Sarah Cole, wondering “what trade her sweetheart would be” saw the coffin suspended in the pseudo crystal ball, all hell had broken loose with the girls. It was at that time that Betty started acting strangely. Tituba was worried that there was witchcraft at work.

Master Parris would never allow it and would be angry if he found out, but Tituba tried to capture the demon by baking a witch cake of rye flour mixed with the urine of Betty and Abigail. She fed the cake to a dog in hopes the cur would lead her to the person who was bewitching the girls, but the dog just wandered around aimlessly, then took off into the woods after a rabbit.

Standing before a bucket of water for washing dishes, Tituba was weighing her options when from another room in the parsonage, she heard what sounded like a banshee on the loose.

Elizabeth Parris was lying on the ground, her arms and legs flailing in the air and spittle spewing from her mouth. She had overturned the dining table, breaking a ceramic pitcher and cutting her arm in the process. Nearby stood Abigail Williams, wide-eyed and gaping.

“Go get Master Parris,” Tituba told the girl and Abby ran from the room.

Tituba knelt down next to the spastic girl and tried to calm her. She managed to grab Betty’s bleeding arm and wrapped her kerchief around it to stem the bleeding. Thank goodness it wasn’t serious, just a long scrape. Slowly, Betty began to relax and by the time Parris and Abigail reached the room, she was asleep in Tituba’s arms. Parris looked around the room at the damage. He had tried to keep this a secret in his own home, but he could not any longer. The girl was having seizures and needed a doctor. He sent Abigail off to find Dr. Griggs, the Salem Town physician.

It took Griggs more than an hour to reach the parsonage, and he listened intently as Parris told him Betty’s symptoms. She was forgetful of chores, she would stare into space and when she came to her senses she would scream. She refused to bow her head during prayer, Parris said, revealing the worst symptom of all. As if on cue, Betty sat up in bed, looked around at the adults surrounding her and brayed like a donkey. Then she pulled the covers off and began walking on hands and knees barking.

Griggs looked at Parris in wonder. He wasn’t a superstitious man by nature and considered himself a scientist, so he was not prone to hasty conclusions. Still, this was clearly not epilepsy. It was not St. Vitus Dance either. Griggs spent several more days in Salem Village studying Betty, and later Abigail, who exhibited the same symptoms. He could not explain it. They ate what everyone else ate. They did not go outside much and had not been bitten by an animal. The girls assured him they had not been drinking ale or cider and they did not smell drunk. Betty and Abby were at a loss to explain their own behavior, but one man Griggs consulted with (quietly) noticed that it seemed the girls were acting out like children would like to act if they were allowed to run undisciplined. Perhaps the best prescription was a sharp spanking? Griggs discounted this advice and called on Rev. Parris.

“Reverend Parris, I fear the Evil Hand is upon them,” Griggs said sadly.

“Witchcraft?” Parris asked, unbelieving. Fear of witches had subsided in recent years after almost five centuries of active witch-hunts. True, even Cotton Mather in Boston had written of his experience with witchcraft in his church, but could it happen here, Parris wondered. How had the Devil been invited into his home to infect his children? What sin had he committed that would make God so angry that He would withdraw his protection? Was it the infighting with those who still embraced Salem Town’s governance?

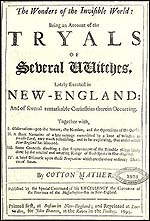

After Griggs had gone, Parris went to his bookshelf. He pulled down Mather’s pamphlet “Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions,” published in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1689.

In it, Mather described the possession of a Boston family that was later traced to a neighbor who had bewitched them. The children were tossed about and bent in odd angles, they emulated beasts, shouted profanities and exhibited many of the same symptoms Betty and Abigail showed. Parris reread Mather’s hysterical screed and noted that the Boston minister showed little mercy to the woman suspected of being a witch.

Mather

“The suspected ill woman, whose name was Glover…gave such a wretched account of herself, that they saw cause to commit her unto the gaoler’s custody,” Mather wrote. “Goodwin (the victims’ father) had no proof that could have done her any hurt; but the hag had not power to deny her interest in the enchantment of the children; and when she was asked, did she believe in God? Her answer was too blasphemous and horrible for any pen of mine to mention.”

Parris put the book aside and was troubled by the thought that one of his own congregation could be enchanting his children. He rushed home in time to find Betty in the midst of one of her spells. Grabbing her by her shoulders, he shook her gently to get her attention. Saliva ran down her chin as she looked at him, wide-eyed.

“Who is it that afflicts you?” Parris asked. “Who is it?”

Betty said nothing, but instead gave a lowing sound like a calf. Parris repeated himself.

“Who torments you?” he asked. “Is it someone here?”

Betty’s eyes rolled back in her head and returned, looking at Parris but not seeing him.

“Is it… Parris looked around, suddenly unable to think of a single name in his congregation. His eyes rested on Tituba, rocking back and forth with a nearly catatonic Abigail on her lap. “Is it Tituba?”

For a second Betty’s eyes focused on his. She was surprised to hear a specific name mentioned; no one had brought up names before, they only asked general questions.

“Oh, Tituba…she…Tituba,” Betty said and went silent.

For Parris that was good enough evidence. He gently laid his daughter down and approached the slave. Panicking, Tituba began talking without thinking. She told Parris about the witch cake and her own fears of sorcery. Beside himself with fury, Parris only heard a confession of witchcraft. He ordered his wife to fetch the constable. Tituba was taken away in chains.

Witchcraft was much too important to be left to one minister in a divided church, and Parris knew it. He would need help investigating the claims and examining the accused. He dutifully reported to Salem Town the accusations and requested that a magistrate take over the case. In a matter of days the affliction had moved from being a private medical matter for the Parris clan to being a colony-wide legal issue. It is hard to draw the line between the law and religion in 17th century Massachusetts; in fact, no line existed. Demonic possession was as likely to be attacked in the courthouse as in the meetinghouse. For the witches of Salem Village, men of the cloth held their fate in their hands.

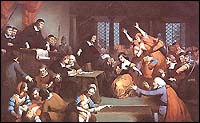

meeting house

Two magistrates the nearest officials of what little government existed in Massachusetts rode out from the town to the village meeting house, each with different expectations, aspirations and beliefs. They were both good Puritans, of course, but one, John Hathorne, was perhaps a little more zealous than his counterpart, Jonathan Corwin. Neither had any formal legal training, but as members of the colony’s legislature, they were as qualified as anyone in the colony to examine the witches. Massachusetts Bay Colony had no judges with formal legal training, nor was there anyplace in the New World where one could be found.

When the word got out that witches had been found in Salem, the magistrates began their research into how to conduct an investigation into the allegations. First, of course, they read their Bibles, which mentions witchcraft only in passing and does not define the term. Then they looked at historical literature, like the Malleus Maleficarum, or “Witch Hammer” (1486), “A Discourse on the Damned Art of Witchcraft” (1608), Increase Mather’s “Essay for the Recording of Illustrious Providences”, and of course, “Late Memorable Provinces” by Increase’s son, Cotton Mather.

stands

Once Hathorne and Corwin arrived in Salem Village in March 1692 they met with the minister and village leaders to explain the process. The problem the magistrates had was just how to go about proving witchcraft. They had easily come to agree that all suspects would be searched for “witch’s tits” any kind of mark on the body that a witch could use to suckle a demon. The best evidence of witchcraft was confession by the witch, but torture was immediately ruled out as a means to extract an admission of guilt. If there was no confession, physical evidence that could be empirically tested was second best.

witch

Spectral evidence would also be allowed, Hathorne said. Cause and effect would be considered established when there was evidence of a curse and of the curse’s result. Hathorne referred to this as “mischief following anger.” In other words, a quarrel between neighbors followed by the death of one party’s cow, for example, was sufficient to suspect witchcraft. Most importantly, Hathorne and Corwin would start with the premise that the Devil could not use an innocent’s “shape” to perform evil. Thus, if a witch appeared to a victim in a dream and tormented the person, the witch could not be innocent.

Supernatural abilities on the part of the accused or a corresponding weakness in an area deemed holy were also evidence of witchcraft. An inability to recite the Lord’s Prayer without error meant the Devil was in control of the accused’s tongue and was compelling evidence of a person’s guilt.

Two leading scholars of the phenomenon of the Salem witch hunts have stressed in their writing that it is unfair to merely shrug off the evidence accepted by the judges as naive and superstitious. Boyer and Nissenbaum point out in Salem Possessed that witchcraft was on the books as illegal by the laws of God, English common law and the statutes of Massachusetts, but it was a very difficult charge to prove. “This was because the evil deeds on which the indictments rested were not physically perpetrated by the witches at all, but by intangible spirits who could at times assume their shape. The crime lay in the initial compact by which a person permitted the devil to assume his or her human form, or in commissioning the devil to perform particular acts of mischief.”

Having laid out the ground rules for the investigation, Hathorne, Corwin and Parris began to root out the Devil in Salem.

If anyone in Salem Village was a witch, it was probably Sarah Good. She was a feisty old woman, somewhere between 40 and 70 years old it was impossible to tell by looking at her, and she had a disposition only the Devil could love. Goodwife Sarah Good had no property to speak of; she supplemented the meager income her husband earned as a day laborer by begging house-to-house. Sarah loved to smoke tobacco that the merchant ships brought up from the southern colonies and she was rarely seen without her pipe. Stuck in the corner of her mouth, the pipe with its rough tobacco smoke had given her eyes a wrinkled, squinting look that only added to her hag-like appearance. Sarah had long been suspected of bringing evil into Salem Village; there were still people who believed she was responsible for a recent smallpox outbreak.

When Ann Putnam the Younger fell ill under an ailment similar to Betty Parris and Abigail Williams, Parris knew Tituba could not be responsible for her enchantment. He asked Ann if it was Goody Good who afflicted her.

“I saw the apparition of Sarah Good, which did torture me grievously,” Ann told him as she recovered from a spell. “I did not know her name until the 27th of February and then she told me her name was Sarah Good, and then she did prick me and pinch me most grievously.”

“Is that all, child?” Parris asked.

“Also since she has appeared several times urging me vehemently to write in her book,” Ann added.

Parris understood this to mean Sarah Good was trying to get the 12-year-old to sign away her soul.

Next Parris met with 17-year-old Elizabeth Hubbard, who was also under a spell.

“Sarah Good came to me barefoot and barelegged,” Elizabeth told Parris. “She pricked and pinched me. I believe Sarah Good hath bewitched me.”

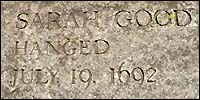

Good

The magistrates ordered Goodwife Sarah Good arrested and brought for examination. Before almost the entire village, the hag was brought forward in chains to stand against the charges. As Goody Good came into the meetinghouse, the afflicted girls there were now about a dozen each erupted into screams of torment. They writhed as if in pain from pinches and needle sticks.

“Sarah Good, what evil spirit have you familiarity with?” Hathorne asked, leaning over the stooped woman from the pulpit.

“None,” the woman answered. The girls shrieked in agony.

“Why do you hurt these children?” he asked.

“I do not hurt them,” she pleaded. “I scorn it.”

Hathorne then turned to the girls who had calmed down somewhat. He had the children look at Good and asked them if she was the one who tormented them. As he did so, they once again started screaming and carrying on. Some fell to the floor in spasms and others merely wept. For Hathorne, the evidence was compelling.

“Sarah Good, do you not see now what you have done?” he asked. “Why do you not tell us the truth? Why do you thus torment these children?”

With little emotion, as if she knew she was a lost cause, Sarah denied the charges again, saying she did not torment them and employed no one to do so. Hathorne persisted. Who is hurting them, he asked.

“Osborne,” Sarah said shrugging her shoulders. “You brought in two others with me, it was one of them.”

Sarah Good was doomed a little later by the testimony of the wife of the constable who arrested her.

“I took notice of Sarah Good in the morning,” said Mary Herrick. “One of her arms was bloody from a little below the elbow to the wrist. And I also took notice of her arms on the night before, and then there was no sign of blood on them.”

Hathorne asked when this occurred.

“Why it was the night she visited Elizabeth Hubbard,” Herrick replied.

The fear that ran amuck in the Good family must have been awesome in its power. Sarah Good’s husband, William, was brought before the magistrates and questioned. He told the court he had noticed “a wart or tit a little below her right shoulder, which he had never seen before.” This was apparently a mark of the Devil. Even Dorothy Good, the woman’s daughter was brought in to testify against her.

In his notes of the hearing, Hathorne wrote later, “Dorothy Good’s charge against her mother: That she had three birds, one black, one yellow and that these birds did hurt the children and afflicted persons.” No record remains of how Hathorne managed to pry this information out of Dorothy.

Tituba assumed she was dead the minute she was taken in chains to the jail in Ipswich. She had confessed to sorcery to her master, and mercy was certainly not a Puritan trait. Her fears were deepened when Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne were arrested and brought to jail with her. If they were jailing good, church-going Puritans on the word of those girls, what chance did she, a savage in their eyes, have?

Unwittingly, Tituba’s fear and resentment worked to her advantage. Since she was going to be hanged, she decided, she might as well not hang alone. So when she was brought before Corwin and Hathorne for examination, she confessed to being a witch.

For three days, the slave spun a tale of midnight gatherings in the forest whereupon the witches of Salem cast spells and summoned demons and familiars to do their work. She told of how Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne had taught her the black arts and how they brought death and misery on their enemies.

Mistress Good is very strong and pulled me to Mr. Putnams whereby I was made to hurt the poor child, she confessed. She took me with her on her pole. I do not know how we got there, for I never saw trees or a path, but presently we were at Putnams.

Tituba told the enthralled congregation of Goodwife Goods control over a wolf, a yellow bird, and a thing all over hairy. As if to confirm Titubas story, Ann Putnam stood and pointed at the rafter where Goods yellow bird was perched. That no one but the afflicted girls could see the yellow bird was of little consequence. It was evidence after all. “With her slave’s adaptability, her only weapon, she caught at every cue the magistrates offered and enlarged upon it,” historian Marion Starkey wrote.

Then Tituba asked for forgiveness. She expressed how sorry she was that she had been forced to hurt the girls, but after all, she was under the control of a witch, as well. Corwin and Hathorne accepted Tituba’s confession and ordered her back to jail. She didn’t know it at the time, but her confession saved her life. Eventually, Sarah Good would be hanged, Sarah Osborne would die of illness in prison, but Tituba was later released to Parris.

While Tituba’s confession spared her own life (and did little to help the others), it made the people of Salem wonder just how large was the witch’s coven in their midst. Although the three women named by the girls were already in jail awaiting trial, no one in Salem was foolish enough to think the Devil had been thwarted. More investigation was certainly required.

Like an avalanche that gathers more force as it thunders down the mountain, the witch-hunt in Salem fed upon itself. Pressed for more details, the girls began giving up more witches. Whether it was because they were in too deep to back out, they truly believed they were bewitched or they were horribly malevolent isn’t clear, but for whatever reason, the affliction spread and the victims became more brazen.

It was Ann Putnam who first accused Martha Corey of sorcery. Martha was a wizened old woman in her 60s or 70s whose initial reaction to the cries of witchcraft in the village had been a cackle and shake of the head.

“Give them a man and they’ll settle down,” she said, walking away from the gossips.

Ann, the apple of her mother’s eye and her pride and joy, was unused to being brushed off like this. So it was not surprising that within the span of just a day or so from Martha’s put-down that Ann began to be tormented by Goody Corey’s “shape.”

A strange coincidence doomed Martha Corey.

The town elders wanted to be sure before accusing a member of the church and a valued citizen of Salem for the past three score years of being a witch. They asked Ann in the midst of being pricked and pinched by Corey’s invisible (to everyone but Ann) specter what the shape was wearing. Ann stared off for a moment and then shook her head sadly.

“I cannot tell,” she replied. “The witch Corey has blinded me.”

The deacons could not let Ann’s accusation go uninvestigated, so they humbly appeared before Goodwife Corey and reported that she had been accused of being a necromancer. Martha reacted in the same fashion as she did when she first learned that witches were loose in the colony. She laughed in their faces. Then she got angry. She gave the deacons what for and then asked the question that would lead her straight to the gallows.

“Could she tell what I was wearing?” she asked, wanting the same answer the deacons had hoped for with Ann.

No, they replied, curious as to why Corey would ask that question.

“I knew it,” Corey cackled again. “I knew it.”

In their minds, the deacons believed the only way Goodwife Martha Corey could know that Ann Putnam could not tell what she was wearing when she tortured the poor child was if Martha was a witch. A warrant for Corey was sworn out the same day and the constable took one of the few levelheaded people left in Salem away in chains.

Joining Martha Corey shortly afterward was Dorcas Good, who had been seen by the girls flying around the countryside on her “pole,” and who was sneaking into their bedrooms at night and biting them. A cunning witch, Dorcas Good must have been, and apparently wise beyond her years. When accused sorceress Dorcas Good joined her mother Sarah in Ipswich jail, she was 5 years old.

Phipps

Massachusetts Bay Colony was in the midst of another crisis that was playing out across the Atlantic Ocean far from where the people of Salem were battling the Devil. In a bloodless rebellion of 1689, the royal governor, a doddering and senile old man, was overthrown by the people and sent packing. The leading theologian in the colony, Increase Mather, journeyed to the court of St. James in London to press King James II for a new charter and governor. After years of intensive lobbying, he received both from his king and was headed back to Boston with the new governor, Sir William Phipps. The charter was not as pro-Puritan as Increase and the rest of the colonists had hoped, but it was better than nothing.

Most importantly, until the colony had a charter and a governor, it was powerless to do anything about the witches of Salem. It could not establish a court to try them, and thus the witches had been sent to Ipswich jail to await trial. If the colonists had proceeded with a trial, any results would have been null and void once the new charter arrived from England.

When Phipps and Mather stepped off the frigate HMS Nonesuch in late spring 1692, the jails of Salem were overflowing with witches. From the time the girls accused Martha Corey, on March 21, through the end of April, 23 people including many of the village’s leading citizens were sent to Ipswich in chains. A posse was sent to Maine to arrest former Salem minister George Burroughs, who was described by one of the girls as “a small black minister” who tortured them and worshiped Satan. He was brought back to Massachusetts in irons.

Even the arrival of the governor did not slow things down. Phipps arrived on May 14, 1692, and by the end of May an additional 39 people had been arrested and accused.

The governor went to work quickly to defuse the situation. He had not expected witches to be his first crisis in the New World, but he handled the situation admirably. Some of the accused had been imprisoned for several months and clearly a court need be established to get justice moving again. Phipps created the Court of Oyer and Terminer to try the accused witches and appointed Deputy Governor William Stoughton as chief judge.

The first witch to have her fate decided by the Court of Oyer and Terminer was Bridget Bishop, although she was one of the last people arrested. Bishop’s most evil spell was to instill in the men of Salem the deadly sin of Lust, because she was an attractive young woman who flouted the Puritan morals by dressing in a modest black dress with a scarlet bodice. Her shape visited the men of Salem village in the middle of the night and beckoned them toward sin and when they fought her off, the succubus of Bridget Bishop would torture her poor victims.

When she was brought before Hathorne for examination, Bishop claimed not to know what a witch was and as she heard the accusations against her, she rolled her eyes in disgust.

The afflicted young ladies of Salem, sitting in front and to the side of Hathorne, did the same, clearly under Bridget’s power.

That and her “smooth and flattering manner with men”, coupled with her arrogant reply of “No!” when Hathorne asked if she was troubled by seeing the young ladies in agony, sealed her fate.

Now, a month later, Bridget was back in Salem, this time in the town’s larger hall on trial for her life.

William Stacey, a 36-year-old yeoman who had been nursed back to health by Bridget when he was down with smallpox was the first witness against her.

“Shortly after I got well,” he told the seven judges of the court, “Bridget Bishop got me to do some work for her, for which she gave me three pence. I thought it was good money. But I hadn’t gone above 3 or 4 rods when I felt for the pence in my pocket and it was gone.”

“Was that the only time she bewitched you?” asked William Stoughton, the chief judge.

Stoughton

“No, milord. Sometime after, in the winter, I was sleeping and felt something between my lips,” Stacey testified. “It was so cold that it did awake me and as I sat up in bed I did see Goody Bishop sitting at the foot of my bed.”

A collective gasp swept through the gallery at the thought of a good Puritan being tempted by such a succubus. Stoughton asked another question. “What happened then?”

“Then she, or her shape, clasped her coat close to her legs and hopped upon the bed and about the room, and then went out!” Stacey testified.

In all, 11 people of Salem village in addition to the afflicted girls stepped forward to accuse Bridget Bishop of witchcraft. They had seen her flying about the countryside on a pole, they knew she controlled cats and birds. One person blamed her for the time the wagon fell in a hole shortly after she had argued with him, and many men complained that Bridget’s shape visited them in the night and urged them to sin. Another witness, who had worked in Bishop’s tavern, testified he had seen rag dolls and puppets in the cellar of her house.

When 42-year-old Samuel Gray testified that he saw the shape of Bridget Bishop looking in at his child and that the child pined away and died shortly after, it was clear Bridget Bishop, the lusty and vain barmaid whose real offense was perhaps too much pride in her appearance, was to hang.

At the end of June, the Court of Oyer and Terminer met for a second time. One of the appointed judges, William Saltonstall, resigned from the court after the hanging of Bridget Bishop, uncomfortable with the ease by which the court dispensed capital punishment. Between June 10, when Bishop was hanged on what was to become known as “Witches Hill” and June 29 when the court met for its second session, the leading ministers of Massachusetts, among them Increase and Cotton Mather, had consulted one another and published a pamphlet which tried to temper the bloodlust of the Salem accusers.

“We judge that in the prosecution of these and all such witchcrafts,” wrote the ministers (most likely Cotton Mather) to Gov. Phipps, “there is need of a very critical and extreme caution, lest by too much credulity for things received only upon the Devil’s authority, there be a door opened for a long train of miserable consequences…”

In the letter “The Return of Several Ministers Consulted,” the theologians urged the court not to convict on the word of accusers alone. Spectral evidence could be considered, they advised, but could not be the sole evidence used to send someone to the gallows. Then they gave their blessing to the proceedings in Salem.

“We cannot but humbly recommend unto the government the speedy vigorous prosecution of such as have rendered themselves obnoxious, according to the direction given in the laws of God, and the wholesome statutes of the English nation, for the detection of witchcraft.”

witch, brought to trial

And so at the end of June, five women were brought before the court to stand trial on the charge of witchcraft. Among them was Rebecca Nurse, one of the leading citizens and members of the Salem Village church. Nurse’s family was quite influential in the village and it was not without some trepidation that the charges were brought against her. Her chief accuser was not one of the afflicted girls, but was in fact Ann Putnam Senior, who had longstanding disagreements with Nurse and her family.

Goodwife Putnam was a sad and vengeful woman whose life had been filled with hardship and misery. She had buried children and lost possessions throughout her adult life, which had greatly affected her mental health and made her susceptible to visions, dreams and omens. Her fragile state of mind left her high-spirited and prone to fits of fancy, which had fatal results for some of the accused. She particularly had it in for Rebecca Nurse, as was evident in her compelling, yet utterly perjured testimony.

“The apparition of Rebecca Nurse did set upon me in a most dreadful manner,” she testified before her rapt audience. “She appeared to me in only her shift, and brought a little red book in her hand, urging me vehemently to write in her book; and because I would not yield to her hellish temptations, she threatened to tear my soul out of my body!”

Caught up in her own fabrications, Ann paused for effect before continuing on in her accusations.

“She blasphemously denied the blessed God and the power of the Lord Jesus Christ to save my soul, and denying in several places of Scripture which I told her of, to repel her hellish temptations.”

Seated in their usual places in the meetinghouse, the family of the elderly defendant could scarcely believe their ears. It was one thing to hear the accusations of hysterical girls, but what this woman was saying was pure folly. Surely the jury would acquit their pious mother and bring a halt to this farce.

But Ann Putnam was not finished. She moved on to recount how the shape of Rebecca Nurse had tortured her even as the real Rebecca stood in front of Hathorne and Corwin for examination.

“I was most dreadfully tortured by her in the time of her examination, insomuch that the honored magistrates gave my husband leave to carry me out of the meeting house,” she said, shuddering at the memory of that awful day in March. “As soon as I was carried out of the meetinghouse doors, it pleased Almighty God, for his free grace and mercy’s sake, to deliver me out of the paws of those roaring lions, and jaws of those tearing bears!”

A snort of disbelief arose from the area where the Nurse family sat, but Ann continued on undaunted.

“Ever since that time they have not had the power so to afflict me until this day,” she finished. “At the same moment that I was hearing my evidence read by the honored magistrates, was again reassaulted and tortured by my before-mentioned tormentor, Rebecca Nurse.”

Having heard the evidence against Goody Nurse and the four others accused that day of the second court session, the jury retired to consider a verdict. On the one hand they had the accusations of so many people, including the poor girls who pointed out that a black-robed man had been whispering in her ear even as victims brought witness against her that very day and that she had brought with her a yellow bird that suckled from the witch’s tit between her fingers. On the other hand, only the girls themselves had seen the man and the bird, and Rebecca Nurse had been bedridden with stomach ailments for the last few months. She had always been such a God-fearing, pious woman who was not a lusty barmaid like Bridget Bishop or a terrible hag like Sarah Good. Rebecca Nurse was a pillar of the community; she could not be a witch. The jury discussed it at length and though the evidence was clear against the others, they voted to acquit Rebecca Nurse of witchcraft as the charges had not been proven.

When they reported their decision to Stoughton, the judge looked down at them sternly.

“Did you not consider the very words of the defendant when she said ‘What? Do these persons give in evidence against me now? They used to come among us!’ Is not that an admission of guilt?”

The jurors looked at Rebecca Nurse, expecting her to say something, to explain what she meant by “they used to come among us.” But Rebecca was old, she was tired and the day had been exhaustive. She was also quite deaf and did not realize that she was being asked to explain her statement. As such, Rebecca stood mute, staring back at the judge. When she failed to respond, some of the jurors mumbled amongst themselves and Thomas Fisk, the foreman, asked leave of the court to reconsider the verdict. In just a matter of moments they returned and pronounced her guilty of witchcraft. Like the others, Rebecca Nurse was sentenced to hang.

Justice was swift in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and only Governor Phipps could save Rebecca. Her family was not willing to give up without a fight and appealed to the governor for a reprieve. Phipps stepped in and, because of her advanced age, the circumstances of her conviction and her life of piety, gave the reprieve. But Stoughton was adamant in his desire to see Salem freed of witches and lobbied hard against Phipps’ decision. Before the reprieve could be delivered to Ipswich and Rebecca Nurse freed, the governor withdrew it.

On July 19, Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth Howe and Sarah Wildes were taken to Witch’s Hill. Sarah Good’s last words, as she was urged to confess her witchcraft were filled with venom. “I am no more a witch than you are a wizard and if you take away my life God will give you blood to drink.”

For her part, Rebecca Nurse went to the gallows wondering what sin she had committed that had angered her God so much that He would end her life in this manner.

Jacobs

A third meeting of the court in early August yielded similar results. George Burroughs, who had left Salem years before and moved to Maine was brought back in chains and convicted of being a wizard. John and Elizabeth Proctor two of Rebecca Nurse’s most stalwart champions were convicted of sorcery, and John was hanged in late August along with Burroughs, John Willard, George Jacobs and Martha Carrier. Elizabeth Proctor was convicted but her life was spared because she was pregnant.

In early September, Martha Corey, Mary Easty (Rebecca Nurse’s sister), Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Dorcas Hoar and Mary Bradbury were convicted of witchcraft and condemned. Ten days later, Margaret Scott, Wilmot Redd, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker, Abigail Falkner, Rebecca Eames, Mary Lacy, Ann Foster and Abigail Hobbs were convicted. Hobbs, Foster, Eames, Falkner and Parker confessed to witchcraft to save their lives, but by the end of the month the others would all be dead.

Before his wife was imprisoned as a witch, Giles Corey wanted to travel from his farm to Salem village to watch the spectacle. Martha, who was every bit as feisty as her 80-year-old husband, later testified that she hid his saddle, but that Giles ended up going anyway.

A long-time opponent of Thomas Putnam, whose wife and daughter were both apparently possessed, Corey wanted to attend the examinations of Tituba, Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne not because he believed them to be witches, but because he was already an outspoken critic of the entire affliction and its consequences.

Corey was one of the few people who stood up in the early days of the hunt and advised that perhaps a sharp spanking would rid the afflicted girls of their demons.

Corey and Putnam were foes going back to the days of George Bayleys service as minister in Salem village and had not seen eye-to-eye since. So it was no surprise to those who had already seen through the adults who participated in the witch-hunt that Putnam would swear out a complaint against his long-time rival.

With his wife already in prison, Giles Corey was brought before the magistrates to face the charges of the Putnam family that he had bewitched them at various times in the past.

The examination in April had been perfunctory. Ann Putnam testified to the usual requests of Coreys shape demanding she sign his book and when she refused, pinching and piercing tortured her. Then, 19-year-old Mercy Lewis claimed the same affliction and Sarah Bibber testified that she saw Giles afflicting Lewis, Putnam, and Mary Wallcott. Faced with this overwhelming evidence, Giles Corey was taken to join his wife in irons. They would languish in the jail for five miserable months awaiting the arrival of Governor Phipps and the creation of the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

By the time his case was called for trial, Corey had a good idea of what was in store for him and he wanted no part of it. He was unwilling to plead guilty and throw himself on the mercy of the court and he well understood that fighting was not going to do any good. He had seen Bridget Bishop hanged in early June and the others who went in mid-July and in mid-August to the same fate. He knew as he was brought for a grand jury examination on September 8, 1692 that he would not live to see October.

Standing before the judges, Corey took the only way out he knew. He refused to enter a plea. Under English law, no man could be tried without uttering a plea, so the court was helpless to proceed. Corey knew this would not save his life, for the judges would keep at him until he entered a plea. But he also knew that by keeping his mouth shut, his estate would not be forfeited to the colony after his death. He had already signed over his farm to his sons-in-law, but that would not keep the government from seizing it after they hanged him. If he died in prison without pleading, they could not touch his property.

Deputy Governor William Stoughton, the chief magistrate of the court, had no plans to let Corey languish in prison. One way or another, he thought, Corey would plead. A week after Corey stood mute in his court, Stoughton had the old man brought before him and asked once again for a plea. Corey stood mute.

You leave us with no alternative, Giles Corey, Stoughton said. The Court orders you subjected to peine forte et dure until such time that you see fit to enter a plea to the charges against you.

The constables standing behind Corey had to grab the old man before he hit the ground, as his knees gave way when he heard the order of the court.

Members of the congregation were as surprised as Corey to hear what Stoughton had ordered. Peine forte et dure, or pressing to force a plea was illegal and had been for some time. However, no one dared stand up to Stoughton.

Pressing involves placing heavy stones atop a prone victims chest, making it impossible to breathe. If the victim is fortunate, the ribcage will collapse and death will be quick, if not, slow suffocation waits. The stones are not added all at once, but a few at a time, giving the victim plenty of time to think about recanting his stance.

A few days later, in the yard of the Ipswich prison, Giles Corey was stripped naked and laid on a wide board on the ground. Another wide board was placed on top of him and large rocks and bricks were added until he was gasping for breath. A jailer knelt down near his head and turned his ear toward Coreys head. He shook his head and stood up.

Continue, Stoughton said, without emotion.

More weight was added and a groan erupted from beneath the pile.

Stop, Stoughton said. He waved to the jailer, who again knelt next to Coreys head. Stoughton could see Coreys lips moving and was delighted that the old man had seen fit to change his mind. The jailer looked at Coreys face for a moment. The old mans eyes were closed, his nostrils were flaring and his mouth was wide open as if trying to catch every bit of air possible.

Then the jailer stood.

Is he ready to enter a plea, constable? Stoughton asked.

No, milord, the man answered.

Then what was he saying?

He said More weight milord, the constable said.

Stoughton looked angry. Then let him have it, he said.

They added more weight on top of the pile until Corey made a sound like a loud, rattling gasp. Stoughton waved the prisoners adding the stone away. He himself bent down next to Corey.

Think of your soul, man, he said to the old man. Enter a plea and let God be merciful.

But it was too late for Giles Corey. If in fact he was a wizard, the only judge he would face would be his God.

courthouse where witch

trials were held

The death toll was mounting. Three days after Giles Corey was pressed to death, eight more witches Corey’s wife Martha among them were hanged, bringing the death toll to 20 (19 hanged, one pressed to death). Three people including Sarah Good’s nursing baby had died in prison awaiting trial. At least 40 people had been jailed awaiting trial, several had escaped with the help of family and friends and many simply left the area until the storm blew over.

It was now six months from the time Elizabeth Parris started acting possessed and terror swept the colony. Along with their cadre of afflicted friends, Ann Putnam and Abby Williams were summoned to nearby Andover where they pointed accusing fingers at 50 more people, most of them strangers. Emboldened by their power, the Putnam women and several of the more precocious girls started accusing even more prominent people than the likes of Rebecca Nurse, Mary Easty and Martha Corey. They went too far when they accused Lady Phipps, wife of the governor and forced the ministers of Boston to step in.

Increase Mather had been publicly silent since June when he signed the ministers’ letter urging the speedy prosecution of witches. In October, he delivered a sermon that was later circulated around the colony recanting his belief in spectral evidence. Having seen the chaos and bloodlust the witch-hunts had created among the people of Salem, he took a stand that contradicted the guilty-until-proven-innocent belief of the Court of Oyer and Terminer. “Better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person be condemned,” he wrote.

Mather’s pamphlet, “Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits Personating Men,” was extremely influential, especially in the office of his friend, the governor.

A week after Mather delivered his sermon, Thomas Brattle, Fellow of the Royal Society of Science along with such notables as Edmund Halley and Isaac Newton and treasurer of Harvard University wrote in widely circulated correspondence about his doubts concerning the fairness of the accusations.

“If our officers and Courts have apprehended, imprisoned, condemned, and executed our guiltlesse neighbours, certainly our errour is great, and we shall rue it in the conclusion,” Brattle wrote to his now anonymous correspondent. “There are two or three other things that I have observed in and by these afflicted persons, which make me strongly suspect that the Devill imposes upon their brains, and deludes their fancye and imagination; and that the Devill’s book (which they say has been offered them) is a mere fancye of theirs, and no reality: That the witches’ meeting, the Devill’s Baptism, and mock sacraments, which they oft speak of, are nothing else but the effect of their fancye, depraved and deluded by the Devill, and not a Reality to be regarded or minded by any wise man.”

Brattle’s letter made a profound ripple in the colony, and Governor Phipps forbade any further imprisonments for witchcraft. By the end of October, the ministers of the colony were calling for a day of prayer and fasting to consider the course the trials should take. On October 29, Phipps dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer. He did allow Stoughton to continue some trials in a Superior Court, but when Stoughton’s juries brought in guilty verdicts, Phipps immediately pardoned the convicted witches. This infuriated Stoughton who held another session of the Superior Court in Boston in January 1693 but walked off the bench when no further witches were convicted. There would be no more trials. By May 1693 the furor had died down and Phipps ordered any suspected witches freed from Ipswich prison.

“Peoples minds, before divided and distracted by different opinions concerning this matter, are now well composed,” he wrote to a friend before opening the prison gates. Over the next several years, families of the accused witches, especially those who had died either in prison or on the gallows, began petitioning the colony for restitution. Some were successful, others were not.

several of witchcraft

accusations.

The Rev. Samuel Parris would continue on as the minister of the Salem Village church for several years, but in 1697 he was forced out of his position and left Salem forever. He had expressed great remorse many times for his role in the madness that took more than 20 lives and especially regretted the fact that the whole mess began in his own home. To greater and lesser extents, the afflicted girls also publicly expressed sorrow for their roles in the trials. In 1702, Ann Putnam the younger stood before the congregation of Salem Village and apologized for her actions. Dorcas Good, the 5-year-old daughter of Sarah Good, was released on bail shortly after her mother was executed but was emotionally scarred by the ordeal. Her father reported to colonial authorities years later that Dorcas was “quite chargeable” and not in control of her sensibilities.

Boyer, Paul and Stephen Nissenbaum. Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 1974.

Salem-Village Witchcraft: A Documentary Record of Local Conflict in Colonial New England. Boston: Northeastern University Press. 1972.

Godbeer, Richard. The Devil’s Dominion: Magic and Religion in Early New England. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 1992.

Hill, Frances. The Salem Witch Trials Reader. Da Capo Books. 2000.

Mather, Cotton. Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions. (1684).

Starkey, Marion Lena. The Devil in Massachusetts: A Modern Inquiry into the Salem Witch Trials. New York: Anchor Books. 1949.

University of Virginia. The 1692 Salem Witch Trials: Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. 2002.