The Columbine High School Massacre — Rampage — Crime Library

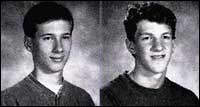

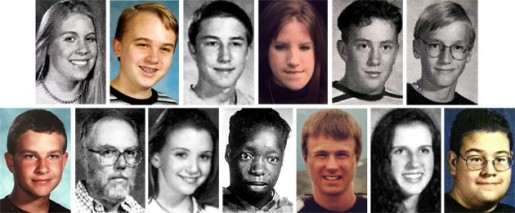

The morning of Tuesday, April 20, 1999 started much the same as any other day in the middle-class town of Littleton, Colorado. None could know, as they went about their normal business, that beneath the calm, an anger had been raging in the hearts and minds of two young men, Eric Harris, 18, and Dylan Klebold, 17. At 11:35 a.m. on that fateful Tuesday, the 110th anniversary of Adolf Hitler’s birth, the two teenagers began a rampage through the corridors of Columbine High School that ultimately ended their lives. In their wake they left 13 dead, 25 injured, many seriously, and a town shaken to its core.

Eric and Dylan had arrived in the school parking lot and entered through the back cafeteria door. They were wearing the long black trench coats that were the trademark of the small clique of students, “The Trench Coat Mafia,” of which they were peripheral members. It was not until the teenagers began firing, from the semi-automatic weapons they had carried, concealed under their coats, that students and staff who filled the cafeteria realized that something was wrong.

Teacher and coach Dave Sanders was shot twice as he attempted to herd as many students as possible out of the cafeteria and away to safety. His quick thinking and bravery saved the lives of many students but, unfortunately, at the cost of his own. By the time he was able to get out of the cafeteria he was bleeding heavily from gunshot wounds to his chest and shoulders and was already coughing up blood. Students attempted to stem the blood flow from Sanders’ wounds, as they cowered behind desks and tables in terror, but he died shortly after rescue teams finally reached him.

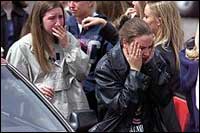

As Harris and Klebold marched through the building, heading toward the library, students and teachers fled. Some hid in bathrooms, some in storage rooms; others had no more protection than the tables under which they had crawled. From outside the building, police and SWAT teams who had begun to arrive could hear the sounds of gunfire and explosions. Students poured out of doors and windows, crying, screaming, some with injuries. They fled as far from the building as they could go. Ambulance workers and police tried to keep track of them as they made their escape. The injured were tended to as the SWAT teams tentatively entered the building, not knowing what was in store for them.

Homemade bombs and explosive devices were found planted around the building. The first priority was to evacuate the school before any of them could detonate. As the police scoured the ground floor looking for bombs, victims and the persons responsible for the carnage, Harris and Klebold were continuing their “mission” on the second floor, hunting down any stray students who were hiding in classrooms. In the library, students who had only moments before been studying were shot down in a blaze of gunfire. Several survivors later reported that Harris and Klebold were smiling and laughing as they shot their fellow students. The last shots heard were at 12:30 p.m. when Harris and Klebold took their own lives.

SWAT teams still did not know how many shooters there were, whether they were dead, or quietly waiting to ambush the police. As each bomb was located, it had to be defused. Students, injured and frantic with fear, had to be escorted from the building to ensure their safety. Each one was also searched for bombs and weapons. It was not until 4:00 p.m. that police declared the building secure. All survivors had been evacuated. The bodies of the two killers were found with their guns in their hands and explosive devices hidden under their coats. Police were able to announce the death toll, including the shooters, as being 15.

All of the six district hospitals had been put on alert as soon as news of the shooting had been reported by the school’s security guard at 11:35. They had swung automatically into emergency procedures. By 12:00 p.m., when the first of the victims began to arrive, they were ready for anything. Twenty- five people were admitted for treatment. Twenty-three had bullet wounds. Three were in a critical condition.

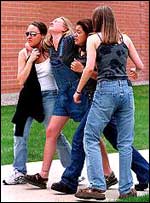

Terrified parents flocked to the school, watching helplessly as students ran from the building, hoping to catch a glimpse of their sons and daughters. In the midst of the chaos, someone began to organize a list of all known survivors. Parents read through the lists, searching for the names of their children. Many would have to wait a long and agonizing time before word of their children would bring relief. For others, the relief would never come.

When the sun set that night, it was on a different Littleton. Everyone in the town was to be affected by the tragic and frightening events of Tuesday, April 20, 1999. They were no longer innocents. No longer could they live secure in the knowledge that such things could never happen to them. It had happened. The next few months would bring the painful grief, self-recrimination and blame that is a natural process of coming to terms with such a violent and tragic event.

Over the next few days, as citizens of Littleton erected memorials and held services for the fallen, police and SWAT teams cordoned off the school, which was considered a major crime scene. The bodies of the dead lay where they fell until nightfall on Wednesday, April 21. Families whose children were still unaccounted for waited nearby for the final identification of the victims. Unable to face the worst, they desperately held to any other possible explanation for why their children had not yet been found, hope not leaving them until the last, when they heard their children’s names called from the list of the dead.

Schools in the district were closed on Wednesday as students and parents alike came to terms with the horror. Columbine would close for the rest of the school year. Many students would express their reluctance to ever return. Mourners from all over the district met at Clement Park, not far from the school, attempting to gain some solace in the other mourners around them. Flowers, candles, and posters were laid at makeshift memorials, as much for the living as the dead.

Wayne and Kathy Harris and Sue and Tom Klebold, the parents of the two teenage shooters, sat stunned in their homes as police searched for bombs, weapons and other material that might help them to understand what had occurred on Tuesday morning. Filled not only with grief for the death of their own children, they bore the weight of responsibility for the deaths of the people their sons had murdered. They were overwhelmed by disbelief. That their sons could have behaved in the way described by police and witnesses was beyond their comprehension.

It would take many months of intense investigation, in what has been described as the state’s most complex police investigation, before anyone would come close to some of the answers. The answers they found led to more questions, many of which may never be fathomed.

As the police investigation progressed, the background of the two boys gradually unfolded. Initially it seemed that Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold were just two average teenagers — intelligent, well-mannered kids who had come from good homes.

Eric Harris was born onf April 9, 1981 in Wichita, Kansas. His parents Wayne, and Kathy Harris had both been born in Colorado but Wayne’s career as an Air Force transport pilot had meant that the family had moved often. They had lived in Ohio, Michigan and New York. When Wayne Harris retired, he and Kathy chose to settle in Littleton in 1996. There Wayne worked at the Flight Safety Services Corporation in Englewood. Kathy worked at a catering company in the same area. Friends, neighbors and associates of the Harrises in all of the areas in which they had lived described Wayne and Kathy as good people, supportive and considerate of both of their sons.

During his childhood, Eric Harris had played Little League and was a Boy Scout. Eric and Dylan became firm friends soon after the Harrises moved to Littleton. Before long they had linked their home computers and would spend many hours playing video games.

Eric had hoped to be accepted into the Marine Corps but had been informed, several days before the massacre, that his application had been rejected. The reason given was that Eric had been taking the anti-depressant Luvox, which was often used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder. Luvox is a commonly prescribed drug, which normally does not cause any physical or psychological side effects unless taken with other drugs or alcohol. No evidence of drugs or alcohol had been found in Harris’s body after his death.

Dylan Klebold, like Eric Harris, came from a stable middle-class family which was held in high regard by friends, neighbors and associates. Dylan was born on September 11, 1981 in Lakewood, Colorado. He had lived in Littleton for many years with his parents Sue and Tom Klebold and older brother Byron.

Tom Klebold, a former geophysicist, operated a mortgage management business from their family home while Sue worked at the State Consortium of Community Colleges providing accessibility for disabled students. Close friends felt that Dylan began to change after he befriended Eric Harris during 1996.

As far as anyone knew there had only been one incident of criminal behavior in the past. In March the previous year, the boys had been arrested on felony charges of criminal trespass and theft for breaking into a car and stealing some tools. Klebold and Harris had made such a good impression on the juvenile officers involved in the case that they were offered to have their records cleared if they promised to stay out of trouble and participate in a diversionary program. Harris was required to attend anger management classes. Again, he had made a good impression on authorities.

However, it would not take long before a contrasting picture began to emerge. A picture of two young men, angry at the world they thought had wronged them, who had sought, for some time, a way to accomplish their revenge.

It was soon discovered that Eric Harris had a website posted which openly expressed his anger toward the people of Littleton, especially teachers and students at Columbine High School. On this site, Harris had begun to express his desire for revenge against everyone that had irritated or annoyed him. The words “God, I can’t wait until I can kill you people,” and “I’ll just go to some downtown area in some big (expletive) city and blow up and shoot everything I can” were posted as early as March 1998. It was also around this time that both Harris and Klebold began experimenting with pipe bombs, posting the results of their tests on the site.

A number of students told of incidents where Harris and Klebold had bragged that they would one day seek revenge on the “jocks” at the school, whom they felt had ridiculed them and treated them as outcasts. A video made as a school project by the pair showed them walking through the corridors of the school wielding guns, killing all who stood in their way. They had been disappointed when their teacher had not allowed the video to be viewed by the rest of the school because of its violence. Harris was also known for his violent themes in creative writing projects.

Many of their teachers described the youths as being depressed, angry, and admirers of Nazism. In the minds of some teachers, Harris and Klebold had shown many disturbing signs of their violent tendencies; these same teachers had reported their concerns. Unfortunately, no action could be taken against the boys, as they had in fact done nothing to warrant it, although, one of the boys had been suspended the year before for hacking into the school’s computer system. Despite the growing concern of many of their teachers, the Klebolds and Harrises claim that they had never been informed of their sons’ behavioral problems.

The lack of communication between the juvenile authorities, school officials and their parents enabled Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold to maintain the appearance of normalcy to those closest to them, while secretly planning the fulfillment of their angry, violent fantasies.

Police investigations into the worst case of school violence in America’s history began on Wednesday, April 21, 1999. At Columbine High School, the bodies of 12 students were recovered. All had died from gunshot wounds. In the library, the bodies of Harris and Klebold were found with explosive devices attached to them. The four guns they had used in the shooting were lying next to them. They had both died of self-inflicted gun shot wounds. It was reported that, over the next few days, between 30 and 50 bombs and explosive devices were found throughout the school, in cars, the school parking lot and in Eric Harris’s home. A search of the homes of the two teenage gunmen uncovered evidence that suggested to police that Harris and Klebold might have had one or more accomplices and had spent over a year planning and preparing for the shooting. A website and journal owned by Harris confirmed their suspicions.

The first mystery police had to solve was how Harris and Klebold were able to obtain the four guns used in the shooting. The two shotguns and the rifle could have been purchased legally by Harris, who had turned 18 less than two weeks earlier but the semi-automatic, identified as a TEC-DC9, could not be legally purchased by anyone under the age of 21.

It was soon revealed that a close friend of Dylan Klebold had purchased the guns for him at a gun show in the Denver area in November or December 1998. The young woman was identified as Robyn K. Anderson, an 18-year-old student at Columbine High School. She and Klebold had been close friends for some time and, although not romantically involved, had attended the school prom together three days before the shooting. Police investigations concluded that Anderson, who was in the running to be school valedictorian, had no prior knowledge of Klebold and Harris’s plans for the guns and would not be considered as a suspect in the case.

The TEC-DC9 proved to be much more difficult to trace. The manufacturer initially sold it to a Miami-based company, Navegar Inc. In 1994, it was sold to Zander’s Sporting Goods in Baldwin, Illinois. Zander’s then sold the gun to a dealership near Westminster, which sold it, legally, to someone over the age of 21. At some point the gun was sold to Larry Russell, a Thornton firearms dealer, who sold it at the Tanner Gun Show. Although Russell did not keep records of the purchaser, he is definite that the person was over the age of 21. He was not able to identify Eric Harris, Dylan Klebold, or Robyn Anderson as the purchaser from photographs shown to him by police.

For some time police suspected that Chris Morris, a member of the “Trench Coat Mafia” and an employee of a pizza restaurant where Harris and Klebold also worked, may have acted as a middle-man in the sale of the gun to the gunmen. Their suspicions were allayed when a person, who has not yet been identified by police, came forward to tell police that he had sold the gun to Harris. Two men have since been charged with supplying the guns to Harris.

Morris was also questioned extensively by police regarding the possibility that Harris and Klebold may have had one or more accomplices prior to the shooting. Early in the investigation there were as many as 10 people who police considered as possible suspects. Three teenagers, wearing black boots and trench coats, were detained during the confusion after the shooting but were later cleared of any involvement. Another teenager, who fled before the shooting began, is suspected of helping Harris and Klebold to carry duffel bags filled with bombs into the school. A teenager, wearing a white tee shirt was also seen with Harris and Klebold in the parking lot just before the gunmen entered the school, and Klebold’s black BMW was seen 40 minutes before the shooting began, driving near the school with four teenagers inside. Police believe that, while there may have been others with prior knowledge of the shooting, Harris and Klebold were the only shooters.

Harris had indicated in his website, using code names, that his plans included at least two other teenagers. The first name, “Vodka,” was quickly identified as Dylan Klebold but the identity of the other name, “KiBBz,” could not be determined. On this website, Harris’s anger toward students and teachers at Columbine was clearly revealed and his desire for revenge was vented in vivid detail. Also posted was a detailed account of his, Klebold’s and KiBBz’s experiments with making and detonating pipe bombs. Police intended to review the dozen or more cases of bomb detonations in the Jefferson County in the past 12 months to determine whether they could be linked to Harris and Klebold.

Police believe that Harris and Klebold had learned about bomb making on the Internet. Many sites include recipes for pipe bombs and other explosive devices. Although details of the construction of the 30 or more bombs planted at the Columbine school have not been revealed, it has been reported that they were made from materials that could be easily purchased at local hardware stores. As yet, police have been unable to confirm a report from a sales clerk at a local hardware store that Harris and Klebold had bought five large propane filled tanks, nails, wire, screws and duct tape a week before the assault. He also claims that there were two other teenage boys in the car with Harris and Klebold.

Captain Phil Spence of the Arapahoe County Sheriff’s department described some of the bombs as being crude and simple, made of carbon dioxide canisters, galvanized pipe or metal propane bottles. Others, like the one which exploded on the corner of South Wadsworth Boulevard and Ken Caryl Avenue minutes before the attack, were equipped with timing devices and were much more sophisticated. Many of the simpler bombs were primed with matches stuck in one end of the pipes. Harris and Klebold had striker strips attached to their sleeves, which they rubbed over the match heads as they walked past. Despite their simplicity, they were still powerful.

One bomb blew a hole through a wall in the library. The largest bomb, found in the kitchen was made out of a pipe bomb, two propane tanks, and several smaller fuel cylinders. Evidence suggests that Harris and Klebold had opened fire on this bomb when it failed to explode. If they had been successful in detonating this and all of the other bombs they had planted, the death toll could have been as many as three hundred.

In the journal found in Harris’s bedroom, his and Klebold’s intention to kill as many as 500 people had been clearly stated. They had decided to start their attack in the cafeteria at 11:00 a.m., as the highest number of students would be there at that time. Every detail of their intended movements for Tuesday, April 20, 1999 was chronicled in the journal, beginning with an early start at 5:00 a.m. It appears from Harris’s writing that Columbine High School was intended to be just the beginning of their rampage. Their ultimate hope had been to continue the massacre in neighboring homes, then to hijack a plane. The grand finale was to crash the plane into New York City. Only a long trail of death and destruction would have satisfied Harris’s and Klebold’s need for revenge for the perceived wrongs done to them.

Days after the massacre was over, Littleton faced the threat that Harris and Klebold’s death was not to be the end of the destruction. A letter was received by the Denver-area Rocky Mountain News. The note, apparently authored by Eric Harris, blamed their murderous scheme on the parents, teachers, and students of Columbine High. The students were blamed for their ridicule and non-acceptance of those who were different, and the parents and teachers blamed for training them to be sheep. The note ended with the threatening words:

“You may think the horror ends with the bullet in my head, but you wouldn’t be so lucky. All that I can leave you with to decipher what more extensive death is to come is “12Skizto.” You have until April 26th. Goodbye.”

As police made inquiries as to the authenticity of the note, schools in the district made preparations to increase security for the following Monday. The threats were not fulfilled and the police soon announced that they believed the note to have been a hoax.

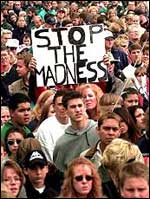

As the initial shock waves from the massacre rippled through the community, citizens were drawn together in their grief. Thousands attended memorial services for the slain, offering and receiving comfort as mourners attempted to come to terms with the tragedy that had befallen them. A spirit of forgiveness was even displayed toward the two teenage perpetrators in the form of two crosses placed alongside those of their 13 victims. Within days however, the mood began to change as grief turned to anger and all that were touched by the tragedy looked desperately for someone or something to blame. Before six months had passed, the need to hold someone accountable had turned the small community upon itself.

Sanders (AP)

Blame was first pointed at the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department. Many believed that it had taken police too long to secure the building, leading to many unnecessary deaths. Teacher and coach Dave Sanders was wounded minutes after the shooting began but died just moments after paramedics reached him four and a half hours later. Police officials quickly defended their actions, explaining that due to the number of undetonated bombs in the building, it had been necessary to go through each room, 250 in total, one by one. Even if they had been told that Sanders was injured somewhere, they would not have been able to get to him any sooner. When asked why police didn’t storm the building and confront the shooters, a commander of one of the SWAT teams, Denver police Lieutenant Frank Vessa answered “We’re not the military. We can’t have collateral damage. Our job was to save the lives of as many innocent as we could.”

With the investigation in full swing, the blame began to shift in a new direction. When it was reported that bombs, a shotgun barrel, a journal and several hand written notes had been found in clear view in Eric Harris’s bedroom, the parents of the two teenage shooters took the brunt of the community’s anger. The Harrises and Klebolds were accused of being negligent parents who had ignored their sons’ violent tendencies. The anger of some was so great that the Klebolds began to receive death threats. This was in stark contrast to the placard, conveying the love and support of friends and neighbors, left on their front lawn immediately after the massacre.

Friends and neighbors of the two families quickly jumped to their defense, claiming that they were good parents who had been completely unaware of their sons’ disturbing behavior. A fellow student who had known Harris well believes that Harris had always hidden his anti-social behavior from his parents, the only reason he would have left things in the open that day was because he knew he wasn’t coming back. According to close friends, the parents were as distressed and mystified by the boys’ actions as everyone else in the community was. At no time had the school informed them of the dark poetry, anti-social behavior or the video they had made. Nor were they informed of several complaints about Harris, which were made to police by parents of another Columbine student.

In response to police criticisms of the Harrises and Klebolds, Randy and Judy Brown reported to a local paper and News4 that police had done nothing when the Browns had complained to police about Eric Harris the year before. The Browns told reporters that they had had many run-ins with Harris over the past two years. In March 1998, they turned to the police when Harris threatened their son’s life. Then they went to the sheriff’s office with copies of 15 pages they had downloaded from Harris’s Internet site. The writings included plans to shoot up the school, details of experiments with pipe bombs and, more specifically, a threat to kill the Browns’ 17-year-old son, Brook. When the Browns had not heard anything from police, they called the sheriff’s office. They were told that there was no record of such a complaint ever being made.

Having had no success with the police, the Browns went to see Harris’s parents themselves. Judy Brown felt that both Wayne and Kathy Harris had reacted as strongly as any normal parent would and they did talk to their son, but Judy believes that Harris had succeeded in deceiving his parents about the seriousness of the situation. This belief was soon confirmed when they received an email, written by Harris, which described how he had fooled his father.

As they still hadn’t received any word from police, and the email repeated Harris’s threats against their son, Judy and Randy decided to make a second visit to the sheriff’s office. They met with a detective who said that the Internet postings they showed him were some of the worst he had seen. When he looked up police records, he found that Harris had been arrested recently for a car break-in. Despite this, no further action was taken and officials handling Harris and Klebold’s break-in charges were not informed of the Browns’ report.

A police report regarding the Browns’ complaints was forwarded to Neil Gardner, the sheriff’s deputy stationed at Columbine High School, but no further action was taken. According to Jefferson County Schools’ spokesman, Rick Kaufmann, the report was not forwarded to the school’s district office but he did not know if anyone in the school received the report.

The district attorney’s office says that it never received a copy of the report. Sheriff John Stone explained that his office received many complaints, known as “suspicious incidents,” in any given period. They are usually given very low priority, although he did concede that the information regarding Harris’s and Klebold’s pipe bomb experiments should have been followed up more thoroughly.

According to Denver lawyer Scott Robinson, who reviewed Harris’s web pages, the reports of building and detonating pipe bombs could have been used as probable cause to persuade a judge to issue a search warrant for Harris’s house.

The need to find someone responsible for the horrific events at Columbine has resulted in the filing of at least 18 lawsuits before the October cut-off was reached. Anyone who may have any degree of culpability in the massacre — gun makers, Harris’s and Klebold’s parents, the school district and the sheriff’s department – will all be required to defend their position, if and when these cases come to court. With several lawsuits being filed against them, the Klebolds have filed their own suit against the sheriff’s department in an attempt to cover the possible costs incurred if the cases against them are successful. Harriet Hall, the mental health worker responsible for providing counseling to the Columbine victims, was not surprised at the dissension that occurred in the community since the massacre. “I’d be worried if there weren’t disagreements… This is a natural response to what the community has been through,” she said.

other for support (AP)

Debate in the House of Representatives over a major concealed-weapons bill ignited a new furor about school safety. The shooting at Columbine, while the worst act of school violence in America to date, was not the first.

- On April 16, 1999, a high school sophomore fired two shotgun blasts in a school hallway in Notus, Idaho. There were no injuries.

- On May 21, 1998, a 15-year-old boy opened fire at a high school in Springfield, Oregon. Two teenagers were fatally shot and 20 people were injured. The boy’s parents were found slain in their home.

- On May 19, 1998, an 18-year-old honor student opened fire in a parking lot at a high school in Fayetteville, Tennessee. A classmate who was dating the student’s ex-girlfriend was killed.

- On April 24, 1998, a 14-year-old student shot a science teacher to death at an eighth-grade graduation dance in Edinboro, Pennsylvania.

- On March 24, 1998, in Jonesboro, Arkansas, two boys, aged 11 and 13, opened fire on teachers and students as they left a middle school building during a false fire alarm. Four girls and a teacher were killed and 10 people were wounded.

- On December 1, 1997, a 14-year-old student was arrested after three students were killed and five others wounded in a hallway at Heath High School, West Paducah, Kentucky. One of the injured girls is paralyzed.

- On October 1, 1997, a 16-year-old boy in Pearl, Mississippi killed his mother then shot nine students, two fatally.

According to a survey conducted in 1997 by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 10% of the participating high school students said they had carried a weapon onto school property. In Colorado, 506 students were expelled during the 1997-98 school year for taking weapons to school. This is an 18 % increase from the previous year.

since the tragedy.

With statistics such as these rising every year, school authorities are at a loss as to what they can do. Large student populations during lunchtimes are impossible to control and it is impractical and illegal to lock children in schools. Many schools, such as Columbine, have law enforcement officers on the premises but their effectiveness is questionable. None of the schools in the Denver metropolitan area have metal detectors permanently in place, as they are impractical and, as Denver Public Schools spokesman, Mark Stevens, said “…if they’d had metal detectors at Columbine, the first fatality might well have been the metal detector operator.” Many experts say schools can take precautionary action by erecting fences around the property to limit access, installing security cameras, and training teachers to spot problem children.

Throughout the country, school administrators have been working with school psychologists to put together a behavior checklist to help teachers spot potentially violent students before any problems start. The intention of such a profile would be to alert teachers and parents of potentially violent students so that they can receive counseling, be transferred to an alternative education facility, or be expelled, depending on the situation.

There are a number of character checklists now available for teachers. The National School Safety Center in Westlake Village, California has created a list of 20 warning signs. The American Psychological Association and MTV produced a guide called Warning Signs In the Memphis Conference: Suggestions for Preventing and Dealing with Student Initiated Violence which includes criminologist William Reisman’s list of 50 indicators. Early Warning, Timely Response: A Guide to Safe Schools was commissioned by President Clinton and distributed to schools nationwide. Compiled by the National Association of School Psychologists, the U.S. Department of Education, and other agencies, the guide identifies 16 features that may distinguish violence-prone children, including social withdrawal, feelings of rejection and poor academic performance.

Many critics of “student profiling” programs believe there is a danger that children who do not reflect a desired image may be unfairly labeled. American Civil Liberties Union spokeswoman, Emily Whitfield says “Not only are students being unfairly targeted but, in some cases, there’s not a whole lot of thought going into it.” Recognizing such dangers, Elizabeth Kuffner, spokesperson for the National Association of School Psychologists warns, “Definitely there are warning signs. Definitely, there are things to look for. But to just say a kid fits this profile, we don’t think this is a good idea.”

While the police investigation into the shooting at Columbine High School has done much to reveal the events of Tuesday, April 20,1999 the question as to why is still very much a mystery.

How do two seemingly normal teenagers become mass murderers? Why is school violence on the increase and what can we do to stop it? How can we protect our children from such atrocities occurring again?

These questions have ignited much public and private debate. Anti-gun lobbyists believe that if guns were not so readily available our children would not be at risk. On the other hand, pro-gun supporters argue that it is people, not guns, who kill. Others believe that violence in the media is poisoning our children’s minds, but isn’t the media content a reflection of the public’s demands? All sides of the debate have some degree of validity, yet none offer a complete answer. Are there much deeper issues involved?

Perhaps our fascination for violence, whether as a participant or spectator, stems from our basic need for control, a need which, when unfulfilled, drives us to exert power over others, the most extreme expression of this is taking the life of another.

You do not have to look too far back in history to see the pattern. Every nation that has lusted for power has won it with violence, and in time, turned that violence in upon itself, ultimately ending in its own destruction. As we finish another millennium we can see that not much has changed except in the form in which it is expressed.

Perhaps in time, if we search deeply enough, we will find the answers. In the meantime, we continue to mourn for those who are cut down at the hands of others, knowing only that it shouldn’t happen.

by Marilyn Bardsley

On October 12, 2002, Associated Press reported that “four videotapes made by the Columbine High School killers — showing the teen gunmen brandishing weapons they used in the attack and donning the clothes they wore — will remain in lawyers’ offices.

“The tapes are evidence in a lawsuit brought by a Columbine survivor against the pharmaceutical company that made an anti-depressant taken by gunman Eric Harris. The parents of Harris and Dylan Klebold had sought to keep the videotapes under lock and key during the trial, for fear they would be leaked to the media. But U.S. District Judge Clarence Brimmer turned the parents down Friday, saying: ‘In preparing a case for trial, you need to have the matters you will deal with to work on, and you need it in your office.'”

Other videos in which the killers said how they were going to carry out the attacks will remain locked up, along with writings by the killers.

Mike Montgomery, a lawyer for the Harris family, said, “the parents do not want to run the risk that the videotapes could be broadcast on television, offered in video rental stores or over the Internet, potentially glorifying the attack.”

The lawsuit was brought by Columbine survivor Mark Taylor against Solvay Pharmaceuticals, which makes the anti-depressant Luvox. Taylor, who was wounded by Harris, claims Luvox made Harris homicidal.

Also as reported in October 2002 by the Associated Press, CNN and other news sources, based on an article in The Rocky Mountain News, records about Eric Harris that previously had been closed revealed that he had told counselors that he had trouble controlling his violent thoughts. When he’d get anxious, his anger would build until it felt explosive. He’d punch walls and think about killing himself.

A year before the massacre, he reportedly made death threats against another boy and that boy’s parents had filed a police report stating that he put messages on the Internet about bombs and mass murder. This incident was investigated, but no action was taken.

Harris apparently told his parole officer around this same time that he thought a lot about violence against others and himself. The parole officer enrolled him in a course on anger management.

Harris was already in a juvenile diversion course with Dylan Klebold, his partner in crime, because in January 1998 they were caught breaking into a van and stealing a briefcase, tools, and a flashlight. They went through the program, but were allowed out early in February 1999, three months before their attack on the high school.

“Eric is a very bright young man who is likely to succeed in life,” news reports quoted a diversion officer as writing. “He is intelligent enough to achieve lofty goals as long as he stays on task and remains motivated.”

Of Klebold, the same officer noted: “Dylan has earned the right for an early termination. … He is intelligent enough to make any dream a reality but he needs to understand hard work is part of it.”

Each teen completed 45 hours of community service, paid fines, received counseling and wrote an apology letter to the person whose van they had entered.

Apparently in their case, the program failed to work. They put on the appearance that everyone wanted to see, but in their private space, they were creating a nightmare. In fact, after the anger management sessions, Harris wrote, “I learned that the thousands of suggestions are worthless if you still believe in violence.” Klebold had been fantasizing since 1997 about getting a gun and going on a killing spree. He had written in a journal that he wanted to die. Together, they appeared to be a self-destructive team.

The disclosure of this sealed report is controversial, but some officials and families are pressing for yet more open files. Many feel that the red flags were all there well ahead of time and should have been acted on more effectively. Apparently there are many documents still sealed that potentially could throw light on a case still shrouded in darkness.

It does seem clear that even as these two boys were meeting with counselors in a program meant to help them, they were already planning their assault. Had they managed to escape, they indicated in journals, they would plant many more bombs to blow things up and then go live on an island. If they couldn’t manage that, they’d hijack a plane and crash it into New York City.

In another development, on Sunday, October 20, 2002, CNN reported that “some parents of children killed in the Columbine massacre praised a new documentary about the killings, saying it contributes to the fight for tighter gun control. Others said the film exploits tragedy.

“Bowling for Columbine, shown Saturday at the Starz Denver International Film Festival, uses the slayings as a launching point to examine violence and gun culture in America. The film is by Michael Moore, the left-wing author and documentary maker known for his film about GM, Roger & Me, and his best-selling book Stupid White Men.”

a video made six weeks before the shooting.

The quest by families of the victims, the media and public officials to fully understand the Columbine massacre in the hope that such a tragic event can be prevented in the future has been a six year battle, fought on many fronts, that is still not over.

In all there were 17 lawsuits filed by victims of the school tragedy who sought to make someone accountable for the tragic events. Those named in suits included school officials, law enforcement officials, the manufacturer of a drug prescribed for Harris – Taylor and Solvay Pharmaceuticals Inc.- gun dealers and three young people who helped the teen shooters obtain guns, in addition to the killers’ parents. All were either settled or dismissed.

While many of the settlements were confidential and several families turned down the money they were offered, the largest single settlement made public was $1.5 million from the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department, which went to the family of teacher Dave Sanders.

The disclosure in the early stages of the Columbine investigation that there had been several incidents in the two years prior to the shooting in which both Harris’ and Klebold’s propensity toward violence were made known to the police, the school and the boy’s parents raised the question of whether this tragedy could have been prevented – could more have been done?

Finding an answer to this question has been a legal struggle of mammoth proportions.

It would take four years for video tapes and writings of Harris and Klebold to be declared “criminal justice records” and therefore available to the public, but still who they should be made available to is being debated. Some argue that much can be learned about warning signs which may help to prevent a future Columbine, while others are concerned that unrestricted public access may only serve to retraumatize the community and may glorify Harris and Klebold and their actions.

The fact that the videos had been made using the school’s video equipment and a copy of one of the videos was found on a school computer fuelled the accusations that the school was negligent in not taking further action to stem the growing violence of Harris and Klebold.

A report compiled by the school’s attorneys that includes interviews with the boys’ teachers, which parents believe could help prevent another tragedy by shedding light on any warning signs that were missed or ignored at Columbine High School, cannot be released because it was compiled to help school officials defend themselves in court from lawsuits filed in the wake of the Columbine shootings, and is therefore, according to attorneys, covered by the attorney-client privilege exception in state open-records laws.

In February, 2004 the Jefferson County Public Schools superintendent declared that the interviews with teachers in the report would never be made public. In an attempt to reach a compromise school’s spokesman Rick Kaufman announced that Columbine staff members would speak with the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence at the University of Colorado.

A notebook, kept by the father of Eric Harris, seized from their home on the day of the shooting, which was a record of dealings with his son, including contacts from law enforcement and his school has also been the subject of much controversy. Attempts by many parents of victims to have the notebook made public in the hope that it would help answer lingering questions about what school and sheriff’s officials knew about Harris before the Columbine tragedy have so far been fruitless. In May 2002 Jefferson County District Judge Brooke Jackson ruled that “items seized from the killers’ homes did not automatically fall under state open records laws.” This ruling is still under appeal.

The sworn testimony of Tom and Sue Klebold, and Wayne and Kathy Harris, taken during a lawsuit filed against them by Daniel Rohrbough’s and other victims’ families, is believed by parents to reveal much about how the next Columbine could be averted but, despite many attempts to have the testimony made public the courts continue to uphold the decision to keep those records closed.

In July 2004 State Attorney General Ken Salazar was involved in negotiations to try to win the cooperation of the parents of the Columbine killers for a wide-ranging study of the deadliest school shooting in U.S. history. To date those negotiations have not been successful.

The revelation that there had been a complaint made against Eric Harris to police on August 7, 1997, a full seven months prior to that made by Columbine parents Randy and Judy Brown sparked a new investigation and again raised the specter of a coverup by police. Colorado Attorney General Ken Salazar launched an independent investigation into the handling of the report in October 2003.

The investigation learned that the 1997 report was made by a deputy, Mark Burgess, and forwarded to investigator John Hicks – the same detective who later handled the Browns’ report and who had a hand in drafting an affidavit for a search warrant for Harris’ home in 1998 that was never followed through on. The fact that part of the Browns’ report was found with the 1997 report indicates that someone in the Sheriff’s department had already made the connection.

In 2001, a judge ordered the sheriff’s office to release the draft affidavit for a warrant to search Harris’ home written with Hicks’ assistance. The affidavit showed that investigators had linked Harris to an unsolved pipe bomb case and that the Browns had met with Hicks on the day they claimed, a fact that had previously been denied by officials.

The report into the investigation was released in January, 2004 showed sheriff’s deputies were well aware of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold – with 15 contacts in six incidents – many months before their horrific April 20, 1999, attack on the school.

Included in the report is the claim by Hick’s that top Jefferson County sheriff’s officials lied to the public after the Columbine tragedy about their knowledge of the killers. Another former deputy claimed that one official, then-Lt. John Kiekbusch, effectively ended a March 1998 investigation of the soon- to-be killers when he decided detectives didn’t have enough evidence to search the Harris home.

Salazar also acknowledged that his investigators were still searching for missing documents, including a file belonging to a former sheriff’s deputy that deals with the 1998 report.

As a result of the investigation Ken Salazar requested Jefferson County District Attorney Dave Thomas, on April 27, to convene a grand jury investigation into lingering questions about events that preceded the attack. It was not clear what criminal charges, if any, could arise from the grand jury’s investigation.

In September, 2004 the grand jury found that:

- In a private meeting with Jefferson County officials a few days after the Columbine shooting it was decided not to disclose a draft search warrant for the home of Columbine killer Eric Harris that had been rejected because at the time it was believed there was not enough evidence to justify the search. Among those at the meeting, held in a conference room in the offices of the Jefferson County Open Space Department, were District Attorney Dave Thomas, then-County Attorney Frank Hutfless and then-sheriff’s Lt. John Kiekbusch.

- It had been alleged that Kiekbusch ordered the destruction of a “pile” of Columbine records and uncovered evidence that key documents were apparently purged from the computer system at the sheriff’s office in the summer of 1999.

- That the meeting was called to discuss the “potential liabilities” of the draft affidavit and “how to handle press inquiries that may arise concerning the document.”

- A Jefferson County sheriff’s deputy, Mike Guerra, spent two hours at the Columbine High School as part of his ongoing investigation into allegations that a junior named Eric Harris had posted violent writings on the Internet, some threatening mass murder. While he was there, he briefed the deputy assigned to the school, Neil Gardner, about the probe. He described Harris and Klebold as “misfit kids that weren’t a problem to anybody.” Columbine Principal Frank DeAngelis, as well as the school district’s spokesman, Rick Kaufman, and attorney, Bill Kowalski, all said they had no knowledge of any visit by Guerra.

- The report by Mike Guerrra, as well as some computer files, had gone missing and as yet had not been found.

- That the daily logs were probably destroyed as part of the normal practice of purging records after the passing of a couple of years.

No indictments were made following the conclusion of the grand jury investigation.

Once again there is no definitive conclusion to be reached – no single event or action that can be held up as the one thing that could have prevented the Columbine School shooting. While in retrospect the signs might seem all too clear, is there anything that the school, parents and police could have done? The school had notified the parents of their concerns, the parents had been involved in discussions with both the school and police, and the police had placed the boys in the standard counselling programs available at the time – should they have done more? Would it have changed the outcome? Hopefully in time, the answers will become clearer.

The following articles were used as reference material for this story:

“Friendly faces hid kid killers”

By Lynn Bartels and Ann Imse

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“AOL freezes shooter’s Web site”

Online pages included pipe bomb information

By Kevin Flynn

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Seeking solace”

A shared grief pulls people into churches and Clement Park

By Carla Crowder and Deborah Frazier

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Security is under siege”

School officials feel handcuffed providing safety for students

By Tustin Amole

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Authorities remove bodies, clear bombs one day after assault”

By Mike Anton

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Massacre hints missed”

Web site pages in ’98 talked of pipe bombs, mass random killings, Columbine dad says

By Ann Imse and Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Trench Coat Mafia shocked by violence”

By Lou Kilzer and Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Police step up search for others involved”

‘Very good chance’ more than two teens involved in pulling off Columbine massacre, police say

By Kevin Vaughan

and Lynn Bartels Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Licensed dealers sold 2 of the guns”

Semiautomatics used at school initially ‘purchased legally’

By Carla Crowder

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Two injuries result in paralysis”

Student who fell from classroom and another who was shot five times recovering in hospitals

By Berny Morson and Joe Garner

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Tapes put sounds, voices to terror”

Recordings of 911 calls from inside Columbine portray first frantic moments of shootings

By Brian Weber

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Klebold’s mom ‘shocked and numb'”

Hairdresser tells of a mother’s pain after son goes on rampage

By Tillie Fong

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Note blames the victims”

‘More extensive death’ will come on Monday, says message allegedly written by gunman

By Kevin Vaughan

and Norm Clarke

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Lawmen defend response times, tactics”

‘They were as quick as any SWAT team,’ says

By Gary Massaro

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Into the heart of darkness”

Two killers lived in suburbs, but inhabited their own twilight world

By Robert Denerstein

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Killers’ double life fooled many”

Parents, teachers, neighbours, authorities and even friends failed to see teens’ dark side

By Ann Imse, Lynn Bartels and Dick Foster

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Mundane gave way to madness”

By Lisa Levitt Ryckman and Mike Anton

News Staff Writers

“Gunmen had it all mapped out”

Journal records details, intent to kill hundreds

By Kevin Vaughan

and Karen Abbott Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Online friend didn’t see evil side of Harris”

By Burt Hubbard

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Neighbors repeatedly alerted sheriff’s about Harris’ menacing behavior”

By Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Klebolds never knew, friend says”

By Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Klebold’s date bought 2 weapons”

Springs gun shop owner says 5 teens in trench coats tried to buy machine gun

By Kevin Vaughan, Ann Carnahan

and Karen Abbott Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Striker patches for igniting bombs suggest rampage carefully planned”

By Gary Gerhardt

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Crosses for Harris, Klebold join 13 others”

By Tillie Fong

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Arrest near for providers of guns”

Sheriff cites ‘good leads’; investigation continues into possible accomplices, purchase of bomb materials

By Kevin Vaughan and Ann Carnahan

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Columbine killers had unknown friend”

By Kevin Flynn

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Gunmen died within minutes”

Police accounts show rampage ended before noon, not long after first shooting reports

By Lou Kilzer

and Steve Myers Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“‘It’s Dylan’ starts spiral of misery”

Family friend helped Klebolds, forced from home by police, through initial shock of finding out their son was a suspect

By Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Gun buyer known as bright, shy student”

Columbine senior ‘stunned’ by shootings, friend says

By Carla Crowder

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Harris told of ambition to blow up Columbine”

Students say attacker was obsessed with explosives; investigators study tapes

By Kevin Vaughan, April M. Washington

and Ann Carnahan Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Police continue search for accessories”

Officials suspect more than 1 person knew in advance of Columbine attack plans

By Kevin Vaughan, Sue Lindsay,

Charlie Brennan and Gary Gerhardt

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Thornton gun dealer sold pistol”

He says semiautomatic TEC-DC9 that was used in attack was bought at Tanner Gun Show

By Dan Luzadder

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Deputy knew of Harris’ threats”

Lawman at school got report that teen was detonating bombs, talking of mass killing

By Charley Able, Ann Imse

and Kevin Vaughan Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“School War Zone”

Many students wounded in shooting explosions, fire at Jeffco’s Columbine High.

By Mike Anton

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Where to place the blame?”

Some blame violence in the media — and even sue over it

By Tustin Amole

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

‘The aftermath: Trauma’s effect on kids”

By Janet Simons

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Parents wait, cry and hope”

Joyful reunion for most, but for others despair

By Karen Abbott

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Area schools increase security”

Bomb scare sends Denver’s South High students home early

By Brian Weber

Denver Rocky Mountain News Education Writer

“Those who weathered Oregon shooting offer ways to cope”

Community must share resources, say experts from Springfield incident

By Janet Simons

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“School has history of excellence”

Columbine academics, athletics win praise

By Lori Tobias

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Jefferson County school officials: Expect increased security”

By Shelley Gonzales

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Fierce debate erupts on Internet”

Trench Coat Mafia fuels argument about stereotyping and labels

By Kevin Flynn

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Quiet loners worried other students”

Trench Coat Mafia spoke about violence, carried reputation for being outsiders

By Tina Griego, Ann Imse

and Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Grief flows across metro Denver”

Owens, wife comfort parents waiting in the gym for news

News Staff

“Hospitals on high alert for disaster”

By Michele Conklin

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Trail of mayhem”

Columbine plunged into nightmare of bullets and blood

By Lisa Levitt Ryckman

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Violence often a silent storm”

Experts can’t prepare for deaths in schools

By Tustin Amole and Dick Foster

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Twins helped others in crisis”

Two brothers united after separately aiding students

By Kevin Vaughan

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Friends, kin comfort wounded”

Families of some hunt for dental records to aid in identifying those who didn’t survive shootings

By Ann Carnahan

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Death goes to school with cold, evil laughter”

By Mike Anton

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Video a blueprint for shootings”

Film made for class shows 2 firing weapons while walking in halls at Columbine, student says

By Sue Lindsay and Bill Scanlon

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“The nagging question: Did others help?”

By Charley Able

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“17-year-old girl ‘shined for God at all times'”

By Lisa Levitt Ryckman

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Afterward, no tidy explanations”

As community wrestles with the unthinkable, those who’ve been there offer no easy answers

By Guy Kelly

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Owens tours eerie scene of deadly rampage”

‘It’s a terrible place,’ governor says after seeing bloodied school

By Dan Luzadder, John Sanko and Karen Abbott

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“‘Mourners recall respectful teen”

John Tomlin ‘always set an example … always extended his hand’

By Dick Foster

Denver Rocky Mountain Denver Rocky Mountain News Southern Bureau

“Columbine students will start classes at Chatfield”

By Manny Gonzales

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Student takes a step to recovery”

Pasquale rests after sleepless nights

By Steve Caulk

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

“Brutal Klebold emerges in accounts”

Survivors say teen was no meek follower as he methodically and sadistically killed

By Kevin Vaughan

and Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writers

“Friends, family mourn latest Columbine victim”

Carla Hochhalter ‘as vulnerable as the kids,’ Jeffco DA says

By Lynn Bartels

Denver Rocky Mountain News Staff Writer

OCTOBER 19, 16:32 EDT

“Columbine Parents Sue Each Other”

By ROBERT WELLER

Associated Press Writer

SEPTEMBER 07, 02:45 EDT

“Schools Begin ‘Student Profiling'”

By BRIGITTE GREENBERG

Associated Press Writer