Francis “Two Gun” Crowley — Live Fast, Die Young — Crime Library

Breathless, sweating, already bleeding from several gunshot wounds, Cody Jarrett races up the twisting steps of a gasoline storage tank until he reaches the top of the huge structure. He surveys the hopeless situation down on the ground. As dozens of police bullets whiz by his head, he fires both his handguns at his attackers who scramble around in the darkness below. Cops run for cover under the iron stairways and behind the complex maze of steel pipelines below.

“Come and get me, coppers!” Jarrett screams. He giggles compulsively as he fires a dozen shots into the crowd below. A police undercover agent, once a former confidant of Jarrett, obtains a sniper rifle and places Jarrett in the crosshairs. He fires one shot, which hits the raving madman in the chest and knocks him to the metal flooring. But Jarrett rises from his knees and laughs at his tormenters.

“What’s holding him up?” the cop says as he chambers a second round. He quickly fires another shot and wounds Jarrett again. This time, he struggles to his feet and, realizing it’s the end of the line, he shoots into the gasoline tank under his feet. A hundred cops at the base of the storage vat run for their lives as a geyser of flames erupts from the metal flooring.

“Look out! It’s going to blow!” one cop screams. As if to cheat the police out of their revenge, Jarrett pumps several more rounds into the metal floor.

“Made it, Ma!” he shouts triumphantly. “Top of the world!” And with those words, the tank explodes in a gigantic mass of flames, sending Jarrett into oblivion and James Cagney into movie history.

This was the final heart-pounding scene of one of the most exciting and memorable gangster films ever made, White Heat (1949), directed by Raoul Walsh. Cagney’s portrayal of a mother-fixated psychotic killer remains one of the screen’s most vivid roles and was frequently imitated in the decades to come. But though Cody Jarrett and the script in White Heat were fiction, not many people are aware that the story was partly based on a true incident.

In the spring of 1931, a furious gun battle took place on New York City’s Upper West Side. The incident involved hundreds of cops, dozens of machine guns, tear gas, grenades and a teenage killer who was consumed by an intense hatred of police. As many as 15,000 spectators watched the clash in which hundreds of bullets were fired into a fifth floor apartment while the barricaded suspect screamed out an open window: “You’ll never take me alive coppers! Come and get me!” His name was Francis “Two-Gun” Crowley, and this stunning “Wild West” shootout became known as the Siege of 90th Street.

He infuriated the police when he repeatedly shot his way out of trouble, and many officers wanted to put a bullet in his head. Crowley was a pint-sized dynamo, standing just over 5 feet tall and weighing only 110 lbs. Warden Lewis Lawes of Sing Sing prison said in 1932 that Crowley’s “clear complexion and general appearance would have marked him as a choir boy.” But like a runaway train, Crowley created havoc wherever he went. Beginning as a car thief, quickly graduating to bank robbery, cop-killing, murder and more, he bought a one-way ticket to hell during a furious crime spree that landed him in the electric chair at the age of 19.

Harlow’s murder

New York City Police Officer Maurice Harlow, 27, was walking his beat in East Harlem on the night of January 15, 1925. He had just been married three weeks before. As he crossed the intersection of 104th Street and Third Avenue, he noticed a taxicab being driven recklessly down the street. Harlow managed to stop the cab and asked the operator for identification. The driver was a local man named John Crowley, 25, who was no stranger to police. He had been arrested at least 11 times in the previous 10 years. Crowley was once charged in the murder of a 17-year-old whose body was found just a few blocks away at 100th Street and Second Avenue. He was later acquitted at a trial when a key witness failed to show up.

When Officer Harlow asked Crowley for his hack license, he became abusive and cursed at the young cop. Harlow then placed the driver under arrest and a fight broke out between the two men. Crowley grabbed the cop’s nightstick and began to pound the officer while a crowd gathered. After a fierce struggle, Officer Harlow managed to get cuffs on the screaming suspect, who swore revenge.

“All right! I’ll remember you!” Crowley yelled, “Your number is 11181. I will come back and get you. I beat a murder before and I’ll beat another one with you!” Harlow took the suspect to the local precinct where he was booked and placed in a cell. The following day, John Crowley was released after paying a fine of $5. He was a free man, but he yearned for vengeance.

At about 10 p.m. on February 21, 1925, Crowley and his wife, Alice, attended a birthday party at 1813 Third Avenue. By the early morning hours, the party had become noisy and neighbors called police. The only officer who responded was Patrolman Maurice Harlow. As soon as the cop appeared at the door, Crowley recognized him. Words were exchanged between the two men and Crowley left the party with his wife in tow. A few seconds later, partygoers heard several shots ring out from the hallway below.

It will never be known exactly what happened in that hallway, but Officer Harlow and John Crowley got into a shootout before they reached the building lobby. Harlow was shot once in the back of the head behind his right ear. He managed to get off a shot before falling to the ground. This shot hit Crowley in the abdomen. Both men continued firing as they struggled to get to their feet. In the meantime, other cops in the area heard the gun battle and came running. They found Harlow unconscious in front of 1810 3rd Avenue, his pistol still gripped in his right hand. A few yards away, cops found another pistol with blood on the handle. A trail of blood led across the street and into the dark vestibule of 1803 3rd Avenue. There, John Crowley was found with a bullet through his stomach and his sobbing wife cradling him in her arms. They cursed the police even as officers tried to help them.

Harlow was rushed to Mt. Sinai Hospital, but he never regained consciousness. Before the ambulance reached the emergency room, the young policeman was dead. Crowley was arrested and shipped over to Bellevue Hospital where he remained in critical condition. Alice was taken into custody as a material witness. She fabricated a story that Harlow had fired upon her husband while she was trying to hail a cab. But when it was revealed that Crowley was a convict out on parole from Elmira State Prison, a public uproar followed.

“John Crowley is a psychopath,” said Dr. Frank L. Christian, Elmira prison superintendent. “It was unfortunate that it became necessary to give him his liberty…no provision is made in our penal institution for the care of the criminal psychopath.” Charges were exchanged back and forth in the press as everyone tried to duck responsibility in Harlow’s murder. On March 10, the arguments became moot when John Crowley suddenly died from his gunshot wounds. By then the story was old news. His death was reported at the bottom of page 12 in The New York Times in a seven-line article titled: “Shot By Policeman: Dies”. The story faded from view, lost in a tidal wave of crime reporting that filled the newspapers almost everyday during that era.

John Crowley had a younger brother, Francis, who was 13 at the time of the shooting. He was a slightly built, painfully sensitive teenager not more than 5 feet tall. When John was killed, Francis became inconsolable, withdrawn and soon dropped out of school. He lived his life in a bleak two-room apartment on West 89th Street with his foster mother. He spoke little to the people around him. But inside of himself, Francis developed a seething hatred for the police who he held responsible for the death of his brother.

One day, he swore to himself, he would get even.

Francis Crowley was born on Halloween 1911 in New York City. His mother, a young German immigrant who worked as a domestic helper, placed him in a foster home when Francis was still an infant. At that time, she was single and unable to care for a baby. “Why should I wreck my happy home for that boy?” she later told reporters, “I am married to a man who has been very good to me but who is the type who might…kill me if he knew my past.” Anne Crowley, the woman in charge of the foster home, or “baby farm” as it was called then, gave the infant her last name. She had very little money but tried to give the child whatever she could and managed to send him to school for a time. But Frank was underdeveloped; he was always the smallest student in class, which caused him to be introverted and lonely. He learned very little and his frustration got the better of him. He never made it past the third grade.

By the time he was 12, Frank was sent out to work a regular job. He got a job in a Manhattan factory and was a good employee. He gave his entire paycheck to his foster mother during those years. “He would bring his pay envelope home and give it to me,” she testified later in court, “I did not suspect anything wrong with him.” Unlike many of his contemporaries, Frank did not do drugs, smoke or drink to excess.

He began to hang around with outlaw gangs in the Bronx who taught him petty crime and how to steal. Because his foster brother, John, was an accomplished car thief, Frank wanted to be just like him. John taught him how to drive, and the little brother became fascinated with automobiles and the thrill of driving fast. While still a juvenile, Frank was arrested for car theft on several occasions, though he never did any prison time. Neighbors of the Crowleys told reporters that during one of his arrests, Frank was beaten badly by the police. Since that day, they said, he harbored a deep resentment of cops; a resentment that exploded into hatred when John was killed on the streets of Manhattan in 1925. But Frank continued his criminal career by stealing cars for the gangs and made more money doing stickups in Manhattan. In February 1931, Crowley was involved in a wild shootout in front of an American Legion club in the Bronx where three men were seriously wounded. A short time later, Crowley shot and wounded a detective who tried to arrest him in a running gun battle in Manhattan. While anxious police searched everywhere for him, Crowley turned up in nearby New Rochelle where he held up a bank at high noon. He managed to escape into the Bronx despite a dozen cops in hot pursuit. It was about that time when Crowley developed the street name “Two-Gun” because he always carried two guns and was quick to use them whenever the situation arose.

At about 10 a.m., on April 27, 1931, a young man who was making a meat delivery in Yonkers drove down Valentine Street. As he passed St. Joseph’s Catholic Seminary, he noticed something odd sticking out from behind a three-foot stonewall. The deliveryman parked his truck and got out for a closer look. He saw a small human hand projecting above the wall.

When police arrived, they discovered the body of a woman who had been shot in the heart. She had been dead only an hour or so. Powder burns on her clothes indicated that she was shot at close range. Investigators determined that she was killed somewhere else and dumped behind the wall after she was dead. Tire tracks were found close by, and a trail of blood led from the tracks to the location where the body was found. Later in the day, detectives were able to identify the victim through her personal papers as Virginia Brannen, 28, who lived in Bangor, Maine. She had moved to New York City just 10 days before. She got a job on West 125th Street in Manhattan at a dance hall called the Primrose Club. Detectives paid a visit to the club and located two people who were in a car with Brannen shortly before she was killed.

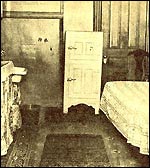

the site of Virginia Brannen’s body

after his capture

A witness named Robert LeClair told cops he was at the Primrose Club partying most of the night with friends including Virginia Brannen. He said that after they left the Primrose they went barhopping, including to some speak-easy clubs in the Bronx. LeClair, one of his friends was a man named Rudolph “Fat” Duringer who had a romantic interest in Virginia. But Duringer seemed upset by something and rarely talked during the night. He said Duringer’s buddy, a young man named Frank, drove the car all night because he was the only one who was sober. LeClair claimed he fell asleep and was awakened by two gunshots a short time later. He said he heard Virginia cry out: “My God! Take me to a hospital!” When LeClair turned around, he saw Duringer with a pistol in his hand and Virginia bleeding badly. Then, Frank pulled the car over and threw LeClair and his girlfriend into the street and sped off. Some time later, Frank and Duringer came back with the car, but Virginia was gone.

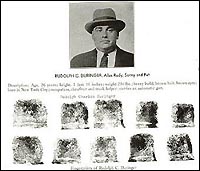

Detectives obtained a home address for Duringer in Ossining, a small town in Westchester County, only 15 minutes from Yonkers. When cops raced to Duringer’s boarding house, they discovered he had left his room the day before and never returned. But through interviews in the neighborhood, cops ascertained that “Frank” had visited Duringer many times and had even stored a car in his garage over the winter. Soon, “Frank” was identified through mug shots which were shown to LeClair and other people from the Primrose. Frank was “Two-Gun” Crowley. In the meantime, Bronx cops found Duringer’s bullet-scarred sedan abandoned on East 155th Street. In the back seat lay a blood-saturated blanket and four discharged .38 cartridges.

On the night of May 6, 1931, just 10 days after the Brannen killing, Patrolman Fred Hirsch Jr., 28, and his partner Peter Eudyce, 24, of the Nassau County police, were cruising along Black Shirt Lane in North Merrick, Long Island. They saw a red Ford sedan parked in a darkened area of the street known as a lover’s hangout. The cops decided to check out the occupants. When they came to a stop, Hirsch exited the radio car and approached the left side of the parked vehicle. He saw that the driver was a young man, no more than 16 or 17 years old. The passenger was a pretty young girl named Helen Walsh, 16, who lived in nearby Roosevelt, Long Island. Hirsch had no way of knowing that the vehicle had been carjacked earlier from a Manhattan garage. He also did not know that the driver was “Two Gun” Crowley.

“What are you doing here?” said Hirsch to the driver.

“Just talkin’,” replied Crowley.

When Hirsch demanded to see his license, Crowley suddenly pulled out a .38 caliber pistol and opened up on the young patrolman. “Well, we were in the car when the cop came up and asked Frank for his license,” Walsh later said. “Frank pretended to reach for it. Instead of that, he pulled his guns and shot the policeman.” Hirsch was hit four times and fell to the ground. But he managed to get off two shots at Crowley who ducked onto the floor of the car. Crowley fired again out the window and hit the cop in the chest. Officer Eudyce took cover behind the police car as Crowley jumped from the Ford and snatched Hirsch’s revolver. As he began to drive away, Crowley shot Hirsch with the officer’s own weapon. “I pushed him away and started to drive off when I noticed he was in agony,” Crowley later told investigators, “I picked up his own revolver from the floor and pointed it at him and pulled the trigger. It fired that time and the policeman lay still.”

As Hirsch lay on the ground mortally wounded, Crowley floored the accelerator as the tires struggled to get traction. Inside the car, Helen Walsh screamed in terror and tried to jump out the window. Eudyce fired at the car, which roared out of the lot in a swirling cloud of dust. The entire event lasted all of 10 seconds.

Later, when cops searched Officer Hirsch for his personal effects, they found a wanted poster for “Two Gun” Crowley neatly folded in his breast pocket.

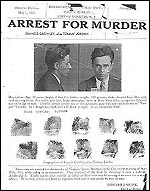

“Francis Crowley…who glories in the nickname of Two-Gun Frank and is described by the police as the most dangerous criminal at large was hunted through the city last night,” began a newspaper article that appeared the next day. All across the city’s five boroughs and Nassau County, photographs of Crowley and Duringer were distributed by police. At first Helen Walsh was believed to have been murdered by the two men to get rid of any witnesses to the cop killing. This belief was reinforced the next day when the stolen Ford sedan was found parked on a deserted side street in Queens. Inside the car were nine empty .38-caliber shells. There was fresh blood in the front and back seats and a bullet hole in the windshield. Crowley’s fingerprints were lifted from the car’s steering wheel. Cops also discovered two bullets embedded in the doorframe.

“There is no doubt that the girl was killed,” said Inspector Harold King. “Crowley must have done it to protect himself. She was the one person who could have convicted him of first-degree murder.”

A massive search was undertaken for the fugitives. Hundreds of cops searched through the swamps and underbrush of Long Island looking for the body of Helen Walsh. New York City police visited all of Crowley’s known hangouts in Queens, Brooklyn and especially the Bronx where he had been arrested several times for car theft. Nassau District Attorney Elvin Edwards issued pubic appeals for help in locating the fugitive. “This brutal murder calls for drastic action,” he told the press. “We want every possible aid from the citizens of the county.” Privately, cops were warned of Crowley’s ruthless reputation and to expect a shootout if he was found.

Meanwhile, New York City crime labs were busy comparing the ballistic evidence in several cases in which it was suspected that Crowley had played a part. Though these forensic investigators lacked the technological advances of today’s crime scene examiners, they were no less tenacious. On May 7, Detective Harry Butts of the New York police., made a dramatic announcement. The bullet that killed Virginia Brannen, bullets fired in the dispute at the American Legion months before and bullets recovered from a gun battle in the Bronx were all fired from Crowley’s gun. Chief of Detectives John Sullivan said that Crowley “does not use drugs as do so many dangerous killers…he just seems to have the impulse to shoot.”

But the police were wrong on at least one point. Helen Walsh had not been killed. She was “Two Gun’s” sweetheart and they were on the lam together. After Officer Hirsh was killed, the young couple located “Fat” Duringer and he eagerly joined his partner in crime. The three fugitives fled into Queens where they abandoned the stolen Ford. They tried to look up friends in the Laurelton neighborhood where Crowley had lived for years but found the area crawling with cops. Jumping into a passing cab, Crowley, Fat and Walsh rode to West 90th Street in Manhattan. There, Crowley looked up an old girlfriend, Vera “Billie” Dunn. After introducing his new girlfriend to her, Crowley threw Billie out of her own apartment and moved Duringer and Walsh in.

Billie was furious at this shabby treatment and promptly told a newspaper reporter what had happened. “He came to my apartment yesterday with that stupid dame, Helen Walsh and that fat slob, Duringer!” she said, “Threw me out of my own apartment!”

“I think that’s pretty tough,” replied the reporter. “By the way, where do you live?”

“303 West 90th Street!” she yelled at the reporter. “Get them the hell out of my place!” But the man didn’t hear her. He was already racing over to the apartment for the newspaper story of his career. On the way, he telephoned detectives from the local precinct and within minutes, a dozen cops jumped in their radio cars.

The detectives raced over the West 90th Street address with their sirens wailing. They knew time was against them since the information provided by Billie Dunn was already 24 hours old. When they pulled up in front of her building, located near the corner of West End Avenue, everything seemed normal. Detectives Dominick Caso and William Mara cautiously entered the lobby and hurried up the tenement steps. Just as they reached the landing on the fifth floor, they bumped into reporters from The New York Journal, including a staff photographer. They had just knocked on the door to apartment #303 when Caso and Mara arrived.

“Who’s there?” asked a high voice from behind the door.

“I’m a newspaper photographer, Crowley!” said one of the men. “I want to get some pictures and talk to you!”

“Beat it!” the voice answered. On instinct alone, Caso suddenly pulled the reporters away from the front of the door. At that very moment, the door crashed open and Crowley emerged with two guns blazing. The detectives pulled out their weapons and returned fire, forcing the gunman back inside. Crowley slammed the door and screamed back at the cops.

“Come and get me, coppers!” he shouted. “I’m ready for you!”

In the meantime, down in the street, more police were arriving by the minute. The gunshots were audible even from the sidewalk and cops were already scrambling for cover. Police brass from all over the borough converged on the scene when it was learned that Crowley had barricaded himself inside an apartment. Police Commissioner Mulrooney arrived within minutes to take charge. As police tried desperately to clear the streets of pedestrians and curiosity seekers, Crowley began shooting out the windows.

“I’m up here! I’m waiting for you!” he screamed. Inside the tiny three-room apartment, Duringer and Crowley prepared for battle. Helen Walsh, terrified out of her skin, jumped under the bed in the corner of the room and remained there for the duration of the fight. Down in the street, cops took cover under their police cars and returned fire at the apartment. Machine guns were brought to the scene and marksmen fired a barrage of bullets at the windows facing 90th Street. A command center was hastily set up around the corner on West End Avenue while more people assembled in the area. Everyone wanted to see what was happening. Every few minutes, Two Gun or Duringer would appear at a different window and let off a dozen rounds at the cops. In return, police fired double-barreled shotguns at the fifth floor, knocking bits of concrete and glass off the building. The debris crashed into the street below, sending people diving for cover under cars and into storefronts. The New York Times called it a “No Man’s Land” and a “battlefront.”

shoot-out with Crowley took place

Emergency units from all over the city descended upon 90th Street and hastily set up their gear. Hundreds of cops surrounded the block and fired continuously at the windows of the apartment. An hour later the crowd had grown to more than 15,000 spectators, some who had to jump behind parked cars to escape being hit by flying bullets. On the roof of 303 W. 90th, a few courageous officers made their way to the roof. They chopped a hole through the ceiling and dropped several canisters of tear gas through the opening. Crowley fired his guns through the roof, sending the police running. Then he picked up the smoking canisters and tossed them into the street. The staccato sound of machine guns echoed through the neighborhood, and small fires broke out along the block where the battle was most intense. A furious rain of bullets crashed onto the police cars below as Crowley cursed and laughed at the destruction.

“You ain’t gonna take me alive, coppers!” Crowley yelled.

Duringer began to panic when the ammunition ran low, and he joined Walsh under the bed. Crowley paced the apartment alternately ducking bullets and pumping rounds into the crowds below. Hundreds of bullet holes peppered the walls of the room. The windows were shattered and the ceiling was in danger of collapse. The smell of tear gas filled the air and a dense fog filled the fifth floor. Every few minutes, Crowley heard cops scattering on the roof above. He fired a burst into the ceiling periodically to keep them on the move.

faced his final showdown

with police

(police crime scene photo)

“You’re yellow!” he screamed at Duringer and Walsh under the bed. During a brief lull in the assault, Crowley sat down on the bed and wrote a letter to be read after his death.

“When I die, put a lily in my hand, let the boys know how they’ll look … I hadn’t anything else to do, that’s why I went around bumping off cops! … Take a tip from me to never let a copper go an inch above your knee … as soon as you turn your back they will club you and say the hell with you … I’m behind the door with three thirty-eights!”

Walsh, taking her cue from her boyfriend, also decided to record her last thoughts for posterity. As Duringer, still cowering under the bed, reloaded with the last of the ammunition, Walsh began her letter.

“If I die and my face you are able to see, wave my hair and make me look pretty…Do my nails all over…I use a very pale pink…I always wanted everybody to be happy and have a good time … I had some pretty good times myself … Love to all but all my love to Sweets (Crowley)!”

Just as Walsh finished her letter, a new barrage of tear gas canisters crashed in through the windows. She screamed while Crowley picked up the bombs and threw them back at the police. Several cops saw him throw the canisters and they fired a burst from their machine guns. Crowley took several hits and was knocked to the floor.

The crowds had become uncontrollable and there was a real danger that pedestrians would be hit by the continued gunfire. Police brass put together a squad of tough, seasoned cops who made their way up to the fifth-floor apartment. After listening at the door for several minutes, they decided to make their move. They broke down the door and rushed inside. Crowley, caught completely by surprise, aimed his .38s at the cops and pulled both triggers. Nothing happened. He was out of ammo. Cops knocked him to the ground, kicking and cursing. Crowley was shot four times and bled profusely. Duringer and Walsh were unharmed. Both were dragged screaming from the burning apartment. When police later examined Crowley’s weapons, they discovered that one of the guns belonged to murdered police officer Fred Hirsch.

On West 90th Street, the crowds had gotten so large, more police had to be called in. When Crowley was brought down in a stretcher, bleeding and defiant as always, spectators cheered his capture. He was tossed into an ambulance, which started over to Bellevue Hospital. As Crowley lay strapped to the gurney, cops found two fully loaded automatic pistols strapped to his legs. The barrels of the weapons were inserted into his socks and the butts were taped to his calves. “Two Gun” intended to shoot it out in the ambulance and make his getaway at the first opportunity.

bed after his arrest

The day after Crowley’s capture, Grand Jury proceedings began in the Hirsch murder case. Crowley was held at Bellevue where nervous guards kept him locked in his room and tied to the bed. His photo had appeared in the New York press many times in previous weeks and he was famous all over the city. “Two Gun” took obvious pleasure in the notoriety, and whenever he had an audience, he played the “bad boy” role to the hilt. Gangsters of that era were sometimes idolized by the public and some were even considered “heroic,” though Crowley never achieved that status. He did have a fan club, however, which consisted mostly of young women and mothers. During his stay at Bellevue, doctors received dozens of phone calls from females who were “concerned” about his health and wanted to know if he would recover.

Investigators questioned him while he lay in bed and Crowley expressed his distain for the police. “I learned to hate cops because they were always suspecting me,” he said, “and on account of my stepbrother having been killed in a fight with a patrolman!” Detectives wrote down every word and before Crowley was transferred out to Long Island the next morning, they had accumulated a litany of statements to be used against him in court.

Patrolman Fred Hirsch was the third Nassau County police officer killed in the line of duty. On May 9, 1931, at 11 a.m., Hirsch’s body was transported to the Holy Rood Cemetery in Westbury, Long Island. Several thousand people attended the funeral including more than 600 members of the Nassau County Police Department. Meanwhile, “Two Gun” was carted to Nassau Hospital where he was handcuffed to the steel railings of a bed on the fourth floor. Two uniformed officers guarded him closely. District Attorney Elvin N. Edwards and County Judge Lewis J. Smith held the arraignment in Crowley’s room at noon that day. When the judge asked Crowley how he pleaded, the accused killer replied in a strong voice.

“Guilty!” he said. But the judge informed the defendant that a plea of guilty to first-degree murder was not acceptable under the law. There had to be a trial.

“Anything you say!” replied the teenager, “All I want is to get my girl out the jam and get it all over with!” The judge asked Crowley if he had any money to hire an attorney. When Crowley said he was broke, Smith appointed Charles R. Weeks, a former county DA to represent him.

“Isn’t there any way we can get this thing over with before that?” said Crowley as he attempted to sit up in the bed. “Aww, I know I’m gonna burn,” Crowley told reporters, “What’s the use of fooling around wit’ a trial, a bunch of lawyers and all that bunk!”

photo

In the meantime, Duringer was being held in the Bronx for the murder of Virginia Brannen. Prosecutors were already building a case against him while Helen Walsh was being held as a material witness in a secret location. Rumors surfaced that the Brannen girl was killed as a favor for an unknown party who paid Crowley and Duringer $300 for the job.

“Nonsense!” said Inspector Harold King, chief of Nassau County Detectives to a reporter from The New York Times, “That murder was a sordid sex murder and the payment of money had no connection with it.” Duringer had already made a confession to detectives and explained why he killed her. “She told me she was going to marry someone else,” he said. “I loved her and so I shot her!”

In the meantime, the landlord of a building, damaged during the siege of 90th Street, submitted a bill to the city for damages. It claimed $2,824 for “loss of good will, tenants and trespass, invasion and willful destruction” caused by more than a thousand rounds fired by police during their capture of “Two Gun” Crowley.

The wheels of justice turned a lot faster during the 1930s than today. By May 25, an astonishing 19 days after the slaying of Hirsch, prosecutors were ready for trial. During jury selection in Nassau County, which lasted two days, Crowley sat in the courtroom chewing gum and smiling at the prospective jury pool. As he examined each juror, he made derogatory remarks loud enough for the court to hear. He referred to one as “baldy” and another as “too slick looking.” Surrounded by three guards at all times, Crowley took charge of his own defense and barked orders to his defense counsel, Charles Weeks. “I’m poison to those guys who’ll be on that jury,” Crowley complained. “They’ll give me the business for killin’ that copper if it’s the last thing they ever do!” But once the jury was acceptable to both sides, testimony began on May 26.

prints

District Attorney Edwards began his opening statement by telling the court that Crowley was a vicious killer who never gave Hirsch a chance. He said the teenager was a career criminal who deserved the death penalty despite his age. As Edwards gave the opening statement, Crowley grinned and frequently turned to the spectators behind him to smile at the numerous young girls in the audience. Before entering the courtroom, Crowley always primped up his hair and kept up a neat appearance. He wanted to look good for his fans and he frequently bantered with spectators during breaks in the trial.

First to take the stand was Helen Walsh, still feeling the terror of the siege on West 90th Street. She said that she went for a ride with three other youths in Crowley’s car the night before the killing. She didn’t know the car was stolen but suspected it wasn’t his. When Crowley parked the car on Black Shirt Lane after midnight on May 6, she became a little frightened, she said. At the same moment she saw two cops approach the car from the back, and she described the ensuing shootout. She also said that Crowley broke away the windshield to destroy the bullet holes and also switched license plates before he drove into New York City.

The two passengers in the car the night before also took the stand. They told the court that Crowley admitted shooting a New York detective in Manhattan who tried to arrest him and that Crowley said he would “shoot it out with any cop who tried to take me!” Patrolman Peter Eudyce testified that when Crowley opened up on Hirsch, he had almost returned to the police car. When the shooting started, he said, he fell to the ground on the slippery grass but managed to empty his six-shot revolver at Crowley. Then, Eudyce said tearfully, he watched helplessly as the red Ford sped away while his partner lay dying in front of his eyes.

“That’s him,” Eudyce said, pointing to Crowley who slumped down into his seat. “That’s the guy who shot Fred Hirsch! That’s him!”

court under guard

On May 28, Crowley took the stand to give his version of events, showing no remorse whatsoever for the death of Hirsch. His appearance was meant to convince the jury that he was a “moral imbecile,” as his attorney described him in the opening statement. Crowley told the jury that he never finished school and couldn’t read or write. “Listen, I’m only a little fellow,” he said, “and I’ve been kicked around all my life by a lot of guys who were bigger and tougher than I was. I got pretty sick of it too!” He said that he also had two serious falls when he was younger, which rendered him unconscious and presumably more likely to kill a cop. Crowley said he committed his first crime in 1929 when he began to steal neighborhood automobiles so he could take friends for a ride. He said he became involved in a shootout at the American Legion in the Bronx the year before and decided that he liked it so much that he would become a “hold-up man.” Crowley said that he went to Philadelphia where he bought “two guns, two blackjacks, two pairs of brass knuckles” and ammunition.

(police evidence)

“When I’ve got a gun in my hand,” he said, “I’m as big as the biggest cop, get me? And when I have my shootin’ irons, I’m not afraid of anybody, see?” Crowley showed no remorse for killing Hirsch. “I shot three times, winged him in the arms and he started to slip,” he said. “But his hand with the gun was still inside the car and then I fired about five more.” Crowley said he “grabbed the gun the cop had. I was pretty nervoused up!” Prosecutors pointed out that Crowley’s statements were different than those he gave to detectives after his arrest when he told reporters: “He was laying there on the ground and I couldn’t stand to see the poor devil suffer! So I got out and fired two more shots into him so he’d die quicker! You should have seen that other cop run when I started pegging those shots!”

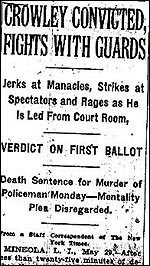

On the morning of May 29, only 23 days after the killing of Officer Fred Hirsch, the jury found Francis “Two Gun” Crowley guilty of first-degree murder. They deliberated less than 25 minutes. A death sentence was mandatory under state law. Crowley accepted the verdict without uttering a word. But on the way out of court, he tried to stop to say goodbye to his foster mother who was in the front row. Guards restrained him and Crowley immediately went on a rampage. He attacked a deputy sheriff and prison guards. The police, who were at the doors of the courtroom, joined in the melee as the brawl spilled into the spectator’s gallery. People screamed and ran for cover as Crowley elbowed cops in the face and swung his manacled arms at the guards. Cops used their blackjacks on the crazed teenager and dragged him screaming from the courtroom. In the hallway that led from the courtroom to the jail, guards could be seen beating on Crowley while he cursed them loudly for everyone to hear.

“It was those policemen again,” Anne Crowley told the press, “It’s always that way. They wouldn’t let me kiss him!” Outside the sight of the jury, Crowley was placed in a straight jacket as he spit in the faces of angry cops. Following the verdict, the jury foreman thanked the police for their conduct during the trial. “We want to express our appreciation to the district attorney and his staff,” he told reporters from The New York Times, “and to the police for their treatment of the prisoner since his capture.”

“Two-Gun” Crowley was one of the youngest convicts on Death Row at Sing Sing. Only 19, he looked more like 16. When he arrived on the morning of June 1, 1931, Warden Lawes said “he had about him the pompous air of bravado and a daredevil mentality.” When he was searched that first day, a sharpened metal spoon was discovered in one of Crowley’s socks. When asked what he intended to do with the weapon, Crowley replied simply, “Try and guess!” He refused to accept any guilt for the Hirsch murder and insisted he was innocent.

“I just defended myself,” he told guards during processing into the prison. “That’s all I did to get this deal!” he said.

Crowley chewed gum incessantly and wisecracked his way through the admissions procedure. His pint-sized stature belied his hostile and confrontational nature. Of course, his murderous reputation had preceded him, causing most of the other prisoners to keep their distance. He was assigned #84567. He immediately trashed his cell, destroying everything in sight. He broke up the furniture and threw the bedding out through the bars. Somehow, he managed to set a fire. He stuffed the toilet with clothes and caused a flood. As a result, he was forcibly removed from his cell and placed in solitary confinement. All items were eventually removed from his room. He was stripped naked and left alone 24 hours a day. A mattress was thrown in to him at night and removed in the morning. All meals were served to him in solitary. He had no contact with other prisoners.

After a few days, the teenager went through a transformation. A bird had flown into his cell and Crowley fed it. The bird returned and Crowley fed it again. Soon, he began to care for the bird and made it into a pet. The guard reported the incident to Lawes who decided to visit the boy. “He seemed none the worse for his caveman isolation,” he said later. “His appearance was animal-like, but tamed…he promised he would be on good behavior if clothing were given to him and…if he could keep the bird,” the warden said. “I consented.”

The era between 1920 and 1940 was the pinnacle of capital punishment in America. At Sing Sing in 1932, 20 men went to their deaths in the electric chair. The following year, 18 men suffered the same fate. From the time Crowley arrived at the prison in June 1931 until his execution in January 1932, he watched thirteen prisoners walk the “last mile”. He became well acquainted with the procedures used on Death Row and sometimes conversed with other prisoners who were waiting for their own executions. He told them what to expect and described in detail what would happen in the death chamber. On December 10, 1931, “Fat” Duringer said his own goodbyes as he stepped into the death chamber for the murder of Virginia Brannen.

“There goes a great guy, a square shooter and my pal!” said Crowley as the big man shuffled down the hall. Robert G. Elliot, Sing Sing’s famed executioner, kept a diary of every execution he performed. Under the entry for Rudolph Duringer #172, Elliot wrote: “‘Big Rudy’ The largest man to be put to death in the chair at Sing Sing … He hung his head as he entered the chamber but he did not falter.”

As the date for his own death grew near, Crowley grew melancholy and for a time, dropped the bravado for which he was famous. He began to draw pictures of bridges and skyscrapers in New York City and constructed miniature models of buildings. “He showed an aptitude for drawing,” said Lawes in his book, Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing, “and his sketch of the death house was quite accurate and comprehensive.” Most of his time was spent in his cell, alone with books and his drawings. “During his last six-months in the death house, he was perfectly happy by himself,” wrote Lawes. When he was with other inmates, however, Crowley reverted back to the “Two Gun” character that was expected of him. “Left to himself, he was a well-behaved, somewhat studious and altogether likeable boy,” said Lawes, who sent the killer a quart of ice cream shortly before his date with death.

Meanwhile, Helen Walsh waited to see her former boyfriend for weeks on end. She came to Sing Sing on many occasions but was turned down time after time. Crowley refused to see or speak with her. “She’s out!” he told the press, “She’s going around with a cop! I won’t look at her!”

On January 21, 1932, at 11 p.m., Crowley was led from his cell and escorted to the death chamber. Holding a 15-inch crucifix given to him by Father McCaffrey, the prison chaplain, Crowley held his nerve. He sat down in the electric chair as nervous guards attached the restraints.

“I don’t think the lower one is tight enough, P.K.,” he said to the principal keeper. Crowley recognized one of the officers as someone he knew from Ossining. “Okay, Sarge!” he called to the man. “Hello, Crowley,” replied Sergeant John Lyons who commanded the work detail. A black leather mask was then pulled down over Crowley’s face.

“My last wish is to send my love to my mother,” he said in a muffled voice. Seconds later, the switch was turned and Crowley was hit with 2,000 volts of electricity. Under the entry for Francis Crowley #178, Robert Elliot described “Two Gun’s” last moments: “Hard boiled to within short time before final date … He entered the chamber with a forced smile asked for his mother and thanked Warden … His was a case of a bad boy looking for adventure.” Outside the prison, Anna Crowley, Helen Walsh and other family members were distraught and had to be carried from the scene. “Two Gun” Crowley was later buried at Calvary Cemetery in New York City.

The Daily News called him “midget Frank Crowley” and “the 19 year old pigmy killer.” Another story described him as “the diminutive little killer” and “a half-pint moron!” Even The New York Times couldn’t resist calling Crowley “the puny killer” and pointed out to its readers more than once that he was “undersized, under-chinned, under-witted.” And his ex-girlfriend Vera Dunn once said, “That guy would kill his own mother!” But it was New York City Police Commissioner Mulrooney who had the final word. After “Two Gun’s” execution, he told reporters: “He was a fake bad man with the soul of a rat!”

This story was researched through official police records as well as the extensive newspaper articles that appeared in the New York City newspapers of January through May 1931 including the New York Daily News, The New York Times and the New York Post. Also the following sources were used:

Brillis, Nick, Police Officer, Yonkers Police Department who provided research and official police records on the murder of Virginia Brannen from the Yonkers Police Historical Society.

Drimmer, Frederick (1990) Until You Are Dead. New York, NY: Windsor Publishing Co.

Elliot, Robert G. (1940) Agent of Death: The Memoirs of an Executioner

Lawes, Lewis E. (1932) Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing. New York, NY: Ray Long and Richard Smith, Inc.

Nassau County Police Department who provided records, reports and photos on the murder of Officer Fred Hirsch Jr.

Squires, Amos O., Dr. (1935) Sing Sing Doctor. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Company Inc.