The Murder Trial of O.J. Simpson — Prologue — Crime Library

“No one enters suit justly, no one goes to court honestly; they rely on empty pleas, they speak lies, they conceive mischief and bring forth iniquity.”

— Isaiah 59: 4,9-11, 14-15

In the beginning it was a double murder, and then it was a criminal trial that dominated public attention as the law tried its hardest to convict a man.

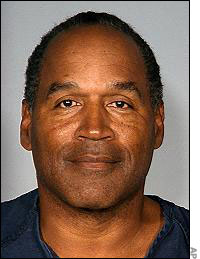

A man who became perhaps the most famous criminal defendant in American history and so easily recognizable that people referred to him by his initials only. It went on for nine months. There were 11 lawyers representing the man in the dock and 25 working around the clock for the largest prosecutor’s office in the country.

It became the most publicized case in US history. It was the longest trial ever held in California, costing over $20 million to fight and defend, running up 50,000 pages of trial transcript in the process. There were 150 witnesses called to give evidence before a jury that was sequestered at the Hotel Intercontinental in downtown L.A. from January until October.

Half way through the trial, the presiding judge, who could so easily have wandered into the whole thing from Alice in Wonderland, decided they needed some recreation and arranged for them to go sightseeing in a Goodyear blimp. For added measure he sent them to the theater and on a boat trip to Catalania Island as well.

No movie or television courtroom drama would have dared to unfold the way this one did, and it was not without coincidence that it evolved in Los Angeles, so often referred to by cynics as “La La Land,” the only place in the world where you look for culture in yogurt cups. The rest of the country became obsessed with the empty, celebrity-dominated West Los Angeles backdrop to the crime.

On CNN, Larry King told his viewers, “If we had God booked and O.J. was available, we’d move God.”

The case received more media coverage and was accompanied by more unadulterated hype than any other criminal trial since the Lindbergh kidnapping-murder case in New Jersey in the 1930s, even exceeding the notorious Manson Family trial of the early 1970s.

The media influence, in fact, became so intense that one poll showed 74% of Americans could identify Kato Kaelin but only 25% knew who Vice President was.

An incredible 91% of the television viewing audience watched it and an unbelievable 142 million people listened on radio and watched television as the verdict was delivered.

One study estimated that U.S. industry lost more than $25 billion as workers turned away from their jobs to follow the trial.

2000 reporters covered the trial. 121 video feeds snaked out of the Criminal Courts building where it was held. There were over 80 miles of cable servicing 19 television stations and eight radio stations. 23 newspaper and magazines were represented throughout the trial, the Los Angeles Times itself publishing over 1000 articles throughout the period. Over 80 books and thousands of articles have already been published, authored seemingly by everyone with any role in the trial.

But why did America go stir-crazy over O.J. Simpson and the “Trial of the Century”?

When the events began to unfold, the lead actor in the greatest soap opera to fascinate the American public in the twentieth century was hardly that important. He had admittedly been a famous professional football star, considered by some to have been one of the greatest running backs in American football history. He had won the Heisman Trophy as the nation’s top college football player in 1968 and his NFL records, mainly secured in his career with the Buffalo Bills, included most rushing yards gained in one season, most rushing yards gained in a single game and most touchdowns scored in a season.

But he had retired in 1979 and drifted into a mediocre to modestly successful career in sports broadcasting and minor movie roles. He was best known as the spokesman for Hertz Rental Cars. When Nicole Brown, his second wife, first met him, she had no idea who he was. When the lead prosecutor against him was approached by a LAPD detective for help in getting a search warrant on a property owned by O.J., she asked the police officer, “Who is O.J. Simpson? Phil, I’m sorry, I don’t know him.”

Yet all three major television networks plus CNN covered the story of his trial in massive detail. A murder trial involving victims known only to their family and friends and a defendant called Simpson, who was less known and recognizable than Bart Simpson, became an epic of media overkill.

If all of this was not enough, the brutal murder of two innocent victims spawned a legal mud fight that questioned the competence of just about everyone involved and created a schism between the black and white population that a CNN poll estimated may have set back race relations in the US by 30 years.

To many, particularly in minority communities, the trial of Orenthal James Simpson became not so much a determination of his guilt or innocence of murder in the first degree, beyond a reasonable doubt, but whether or not a black man could find justice in a legal system designed by and largely administered by whites. To others, many of whom were white, the key question was whether a mostly minority jury would convict a black celebrity regardless of the weight of evidence against him.

To others, the tragic deaths of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman always seemed stage left, as the man on trial for their murders commanded center stage in his fight to prove bigotry and racism were the real issues on trial, using a pack of slick lawyers willing to circumnavigate the parameters of legal etiquette and acceptable courtroom manners to achieve their objectives, transforming their client, an accused double murderer, into some kind of political prisoner.

The dog kept barking late on this foggy Sunday evening, June 12, 1994. Pablo Fenjves, a screenwriter, thought he heard it the first time at about 10:15. Elsie Tistaert, who lived just across the street, also heard it, and when she looked out of her window, she saw the dog, a white Akita, pacing up and down outside the front of 875 South Bundy Drive. Louis Kaupf, who lived next door to 875, returned late from the airport and went out to clear his mail at 10:50. The dog was still barking and trotting up and down in an agitated manner. Just before 11:00, Steven Schwab, who was walking his own dog, came across the distressed animal. It followed him home. There, he noticed that the dog’s belly fur and paws were matted in red.

Schwab asked his neighbor, Suka Boztepe, to care for the dog overnight. He agreed, but as the dog persisted in his restless behavior, Boztepe and his partner, Bettina Rasmussen, decided to walk the dog and try and calm it down. The dog dragged them back to number 875, where it stopped and gazed down a dim, tree-shaded pathway. Following the dog’s stare, they saw a shape of someone lying at the foot of some steps, part of the body sprawled under an iron fence.

At 12:13 a.m., the first LAPD black and white patrol car arrived on the scene in response to a call from Tistaert. In it were Officers Robert Riske and Miguel Terrazas. They went through the entranceway of the off-white stucco, three-level condominium and made their way cautiously up the pathway.

They were walking into a drama that a screenwriter or novelist would have given his eye teeth to dream up. In the early hours of this summer morning, the discovery of two savagely mutilated bodies would spawn a series of events that would obsess the American and world media, exert a stranglehold on the attention of the American public, destroy more than one professional career and, perhaps most importantly of all, change the way people looked at race in America.

That morning however, Officer Riske was mainly concerned about not stepping in a small lake of blood as he proceeded up the tiled walkway where he reached the first body, which lay about 15 feet from the sidewalk. It was a woman, sprawled face down, left cheek pressing into the ground, her right leg jack-knifed under the gate frame to the left and her buttocks pressed up against the first riser of the four steps that led up to the path leading to the front door of the condominium.

She was wearing a short black dress, drenched in the blood that had poured out of wounds to her upper body and throat. To her right, just beyond an agapanthus bush in a small garden enclave off the walkway, lay the body of a man. He was crumpled over on his right side, sprawled against a garden fence. His eyes were open and his light brown shirt and blue jeans were saturated in blood.

After establishing that both victims were dead, Riske and Terrazas radioed for backup. Within minutes, Sergeant Martin Coon and officers Edward McGowan and Richard Walker arrived and went about securing the crime scene and controlling the traffic flow on South Bundy, which was busy even that early in the morning.

At 12:45 a.m., paramedics from a nearby fire station arrived and confirmed that the man and woman lying in the grounds of the condominium were indeed very dead. By then, Riske and another patrol officer had established that the woman was probably Nicole Brown Simpson, the owner of the building and the ex-wife of O.J. Simpson, the retired football player and sports newscaster. Upstairs in their bedrooms, they found her two young children, nine-year-old Sidney and six-year-old Justin, fast asleep. The officers awakened them, got them dressed and arranged for them to be taken to the West Los Angeles Division to await formal identification by a family member. An animal control officer arrived and picked up the Akita, which was taken to a pound in West Los Angeles. At this point in time, the identity of the dead man had not been established.

At 2:10 a.m., West Los Angeles Division Homicide Detective Supervisor Ron Phillips, accompanied by Detective Mark Fuhrman, arrived at South Bundy and carried out a visual inspection of the area, without approaching the bodies or getting too close to the immediate crime scene. By then, Fuhrman’s partner Brad Roberts had arrived, logging in at 2:30 a.m., on the sign-in sheet set up by Officer Terrazas. He was the 18th police officer on the scene by this time.

Shortly after, Phillips was notified that the investigation had been handed over to the Homicide Special Section (HSS) of the LAPD’s Robbery/Homicide Division. Made up of only a dozen investigators, HSS was considered the top murder squad in the Los Angeles law enforcement community.

Division Head Captain William O. Gartland assigned Detectives Third Grade Tom Lange and Phil Vannatter as the lead investigators.They arrived at the crime scene and logged in at 4:05 and 4:25 a.m., respectively.

By this time, no one other than the responding officers had come close to the bodies or the area of their containment. Phillips had summoned a police photographer who had arrived at 3:25 a.m., but his function was restricted to general area photographs because police department policy prohibited him taking shots of the bodies or evidence except under the supervision of a lead detective or a Special Investigation Division criminalist. These are civilian employees of the LAPD engaged in the scientific analysis of physical and chemical evidence materials. Their essential functions are to collect, test and analyze evidence such as drugs, blood, paint, glass, explosives, hair, clothing and other crime-related materials. They are also expected to compile data, maintain records and reports, and present testimony in court as required.

Detective Phillips briefed Vannatter and walked him through the crime scene. Without physically disturbing the bodies, which could only be done by a coroner’s investigator, the two police officers could not be certain of the cause of death of the two victims. The two men never got closer than six feet to the two crumpled figures. They did however see a number of objects adjacent to the dead man.

There was a set of keys, a dark blue knit cap, a beeper, a blood-spattered white envelope and a bloodstained left hand leather glove lying under the agapanthus plant only a few inches from Nicole Brown’s body. There seemed to be a trail of bloody footprints leading away from the bodies towards the back of the property and alongside these, drops of blood trailing in the same direction.

As Phillips, Fuhrman, Lange and Vannatter discussed their strategy, they were told that Commander Keith Bushey, chief of operations for the LAPD West Bureau, wanted them to contact O.J. Simpson in person to make arrangements with him in order to collect Simpson’s children. Fuhrman mentioned that when he had been a patrol officer he had visited the Simpson residence, which was situated about two miles to the north, across Sunset Boulevard. Lieutenant John Rogers, the supervisor of Lange and Vannatter, agreed to manage the crime scene until they returned.

Being the ex-husband and therefore closely connected to Nicole, O.J. Simpson was a potential suspect from the very beginning; however as there was no evidence at this time that directly linked him to the scene of the crime, he was not an actual suspect. There would be much made of this subtle difference in the months ahead.

Within the next 60 minutes, the four detectives would instigate the first in a series of actions that would come to have a major impact on the outcome of the murder investigation that they were just beginning.

At 5:00 a.m., the four detectives set off in two separate cars and made their way up Bundy, north to Sunset Boulevard, west to Rockingham Avenue and north to the intersection of Ashford Street. Here on this right hand corner, number 360, sat the home of O.J. Simpson. Parked outside the gated estate in Rockingham Avenue, facing north, was a 1994 white Ford Bronco, its front wheels on the curb and the back sticking out into the narrow street.

The detectives turned right into Ashford and parked head to tail in the dark street. Their journey had taken less than five minutes. Making their way across to the intercom buzzer situated next to the gate, they tried repeatedly to arouse the occupants without success. As the men were deciding on their next move, Fuhrman wandered around into Rockingham Avenue and ran the beam of his flashlight over the Ford Bronco.

Although it was assumed that Simpson owned the vehicle because there were packages inside clearly identified as “Orenthal Products” and the detectives knew that Orenthal was the “O” in O.J., they nevertheless ran a license check on the plate number through their car radio. Information came back that the Bronco was owned by Hertz Corporation, who was using Simpson as an advertising spokesperson.

As the check was going on, Fuhrman called Lange back to the Bronco and pointed out with his flashlight what appeared to be a blood spot on the body panel near the driver’s door handle. By this time the detectives had ascertained the house telephone number and called it repeatedly with their mobile phone, but had received no answer.

After discussing their options, the detectives decided to enter the property. There were cars parked inside and outside the gates. Lights were visible inside the house; nobody answered their repeated buzzing and telephone calls; there were possible blood stains on a vehicle operated by O.J. Simpson, and his wife lay brutally murdered only two miles away. In their opinion, the detectives were justified in entering into the house. A potential emergency might exist and under such urgent circumstances, real or perceived, the police were permitted to enter a property without a search warrant.

A Westec private security guard had arrived as the detectives were trying to arouse someone and confirmed that Simpson and a live-in maid should be on the property. Concerned that they might be just outside another major murder scene, Fuhrman volunteered to climb over the five-foot-high stone wall and unlock the gate from the inside.

At approximately 5:45 a.m., the four detectives walked up to the front door, rang the bell, and started knocking on its wooden panels. Getting no response, the men walked around the side of the property to a row of three bungalows. At the first one, after pounding on the door, a man appeared who identified himself as Kato Kaelin, a friend and house guest of Simpson. At the next bungalow they aroused an attractive young woman who identified herself as Arnelle Simpson, O.J.’s daughter. Leaving Fuhrman with Kaelin, the other three detectives accompanied Arnelle Simpson into the house to check on the security of the occupants. Finding the house empty they sat down and interviewed Kaelin.

He told the detectives that he and Simpson had gone the previous night to a McDonald’s in Santa Monica, returning to the house later in the evening. He went to his guest bungalow and Simpson had disappeared into the main house. At about 10:45 p.m., while he was talking to his girlfriend on the telephone, he had heard three loud banging noises coming from the rear of the building near the air-conditioning unit. The sound and vibrations were so intense he thought at first it was an earthquake hitting the area, and he grabbed a flashlight and went outside to check for damage.

Outside, he saw a vehicle parked at the gate on Ashford. Simpson had ordered a limousine to take him to the LA airport to catch a “red-eye” flight to Chicago later in the evening. A few minutes later, Simpson left the house and Kaelin and Allan Park, the limousine driver, loaded luggage into the trunk of the car, except for a small black bag which Simpson held. Park then drove off for the airport.

The detectives questioned Arnelle Simpson who did not know the whereabouts of her father, but on contacting his personal assistant, Cathy Randa, she was able to furnish his address at the Chicago O’Hare Plaza Hotel. Hearing that her stepmother had been murdered, Arnelle immediately telephoned Al Cowlings, her father’s lifelong friend who had played football with Simpson throughout his professional career.

As she was doing this, Phillips placed a call to Chicago and spoke to Simpson, telling him his wife had been killed. Although apparently distraught at the news, and concerned about the welfare of his children, at no time did he seek any details from the detective regarding the death of his ex-wife. He told Phillips that he would catch the first available flight back to Los Angeles.

Tom Lange knew that once the media got their hands on the murder story it would be headline news on both radio and television, and so decided to ring Nicole Brown’s family and break the news himself before they heard it any other way. At 6:21 a.m., he reached their home at Dana Point in Orange County and spoke to Lou Brown, Nicole’s father. As he sadly passed on the information, in the background, he heard a woman’s voice screaming and wailing “O.J did it! O.J killed her! I knew that son of a bitch was going to kill her!” It was Denise, Nicole’s sister.

A few moments later, Detective Fuhrman returned to the house after an absence of ten or fifteen minutes to tell Vannatter of a discovery in the garden. Leading the way, he walked down past the swimming pool and behind the guest bungalows to the rear of the one occupied by Kato Kaelin. There on the leaf-covered walkway, illustrated by the beam from Fuhrman’s flashlight, the two men looked down on a bloodstained leather glove, which seemed to be a right-hand match to the one still lying in the garden back at South Bundy Drive.

Leaving the glove untouched for processing by a police criminalist, Phillips and Fuhrman headed back to South Bundy, leaving Lange and Vannatter to determine if the Rockingham estate was potentially another crime scene, connected to the first. Lange eventually left Vannatter and went by patrol car back to South Bundy to the condominium and the two bodies still awaiting investigation and inspection by coroner’s investigators and other criminalist teams.

Left on his own, Vannatter spotted what appeared to be blood drops near a Bentley and a Saab parked in the driveway. They led out of the west gate onto Rockingham Avenue and then to the rear of the white Ford Bronco. Inside, he saw other red spots on the driver’s door and on the console near the passenger’s side of the vehicle. Walking back into the garden, he noticed that the red spots led up to the front door of the house.

At 7:00 a.m., Mark Fuhrman returned with his partner and a police photographer who had been shooting at the South Bundy crime scene. As photographs of the brown leather glove were taken, it seemed certain it was a match for the one found near the two bodies there. The photographer also snapped the apparent blood spots noted by Vannatter. As these blood spots and the glove were found in “plain view,” it was certified as evidence that could be collected without a search warrant.

By now, Vannatter had decided that the Rockingham address qualified as another linked crime scene in the two murders they were investigating and had the entire area sealed off and quarantined. At 7:10 a.m., Dennis Fung, a LAPD criminalist, and his assistant, Andrea Mazzola, a SID trainee, arrived to begin the collection and documentation of evidence under Vannatter’s supervision. They were instructed to catalogue all the blood spots and the glove and then to arrange for the Ford Bronco to be towed to the police garage for further examination.

Leaving Fuhrman to maintain the crime scene, Vannatter then left for South Bundy, joining his partner, Tom Lange there at about 7:30 a.m. He then left and traveled to the West Los Angeles Station to prepare a search warrant in order to enter, search and seize any relevant evidence at the home of O.J. Simpson.

The Murder Trial of O.J. Simpson

To Protect and Serve

When Tom Lange returned to the South Bundy location, he arranged for coroner’s investigators to be available from about 8 a.m. He wanted the next hour to further check out the property, review and document all the evidence at the crime scene. Other detectives, who arrived to assist him, flooded the area, checking out the neighbors, recording car license plate numbers and searching garbage containers for a possible murder weapon.

By now, the media had started arriving in frenzied masses and were taking up positions on a small hill across the street from the condominium. To protect Nicole’s body from the prying lenses of telescopic cameras, and also to protect the evidence on her corpse, Lange arranged for it to be covered by a blanket from inside the house. It was an action that would come back to haunt him in the future, just one of many things that formed the basis for part of the defense procedural strategy in the courtroom saga that lay ahead.

Moving through the area, Lange noted a black Cherokee Jeep parked in the driveway at the back of the condominium. This belonged to Nicole as did the white Ferrari, registration L84AD8, “Late for a Date,” that was parked in the garage. He noted on a banister of a staircase leading up to and into the house, a cup of Ben and Jerry’s ice cream melted in its tub. In a house full of children it did not seem out of place or a significant piece in the jigsaw he was slowly assembling. In the kitchen, a long handled knife sat on top of the stove. Nothing else seemed out of place in the house.

Outside, he followed the bloody footprints and blood drops to the back gate, where he noticed two small drops of blood on its inside lower rung. He moved on, down the pathway back towards the death scene. Near the bodies, he checked the bloodstained white envelope, observing that inside was a pair of eyeglasses.

At 9:10 a.m., the coroner’s investigator and her assistant arrived and were chaperoned around the site by Detective Lange. They stopped to examine the body of Nicole. Her bare feet were clean, indicating that she was probably rendered unconscious before the young male was murdered, and that she subsequently died where she collapsed, never stepping into any blood, not even her own. Her neck appeared to have been slashed, almost severing her head from her body, blood had flowed from the wound down the pathway towards the street, almost to the gate fifteen feet away. Bloody paw prints from the Akita led through the blood and out onto the sidewalk. Across her naked back, Lange noticed an odd pattern of blood spots; they may have come from the killer or the murder weapon.

At 10:15 a.m., Dennis Fung and his assistant arrived, having completed their project at Simpson’s home. They and the coroner’s investigators completed their examination of Nicole’s body, photographing it from every angle, recording its historical position relative to all other objects and the other body, in case of any future dispute arising from any potential defense objections, in the event that the killer would be caught and tried. Finally, Nicole’s lifeless, almost bloodless, body was wrapped in a light gray plastic body wrap and carried out onto the street and into the coroner’s brown van.

The investigators then turned their attention to the bloodstained unidentified male body lying crumpled in the garden alcove off the walkway, near the foot of the steps where Nicole Brown’s body had rested.

He was lying on his right side, his body bent at the waist. His eyes were open, staring lifelessly. His face showed scrape marks and blood had dried and crusted in rivulets from his nose and left ear. His left leg, stretched out over his bent right limb, was saturated in blood. His light brown shirt had been pulled up and was bunched around his back, indicating that the killer may have grabbed him, swung him around in the fight, or even killed him on the walkway, and then for some reason dragged his body to the spot where he lay. His throat appeared to have been slashed and he had other stab wounds to his body and upper left thigh.

After the photographs had been taken and the coroner’s investigators had finished with the body, it was also wrapped in a plastic sheet. Claudine Ratcliffe, a coroner’s investigator, searched the clothing and found a wallet in a back pocket of the jeans. The driver’s license identified the man as 25-year-old Ronald Lyle Goldman. He was six-feet-one-inches tall and weighed one hundred and seventy pounds. Because she identified him, a member of the coroner’s office would notify his next of kin.

As the body was removed to the coroner’s van, Detective Lange and Dennis Fung examined the left-handed glove lying among the tree leaves. It was an expensive-looking extra-large dark brown leather with cashmere lining and a label that read “Aris-Isotoner.”

At about 11:00 a.m., Phil Vannatter returned to South Bundy, having drafted out a search warrant on Simpson’s home, and having it checked, approved and signed off by Judge Linda Lefkowitz at the West Los Angeles municipal courthouse. The detective little knew the anguish this document would come to cause him in the future. He had run the warrant past Deputy District Attorney Marcia Clark and requested her presence at the Rockingham Avenue estate when he conducted the search. A tough and aggressive lawyer, she had tried over 20 murder cases, including the successful prosecution of the stalker who had murdered Hollywood actress Rebecca Schaeffer.

Vannatter had worked with Clark before on other cases and respected her abilities as a criminal prosecutor. He checked with his partner, who updated him on the progress made at the crime scene and then left, arriving at Simpson’s home a little before noon.

There he met Howard Weitzman, a prominent criminal attorney who informed him that Simpson had called him on a mobile telephone and asked him to meet him at his home. Inside the house, Vannatter met up with Bert Luper who also worked in LAPD’s Homicide Special Section and was there to help him examine the property.

As they were discussing the methodology of the search, Vannatter recalls in his book with Det. Tom Lange, Evidence Dismissed, that he heard a commotion outside in the grounds of the estate. On the lawn he saw O.J. Simpson handcuffed and in the custody of patrol officer Don Thompson and Detective Brad Roberts, Fuhrman’s partner. Although Vannatter had told Thompson he wanted Simpson detained on his arrival, he had never mentioned using the handcuffs and he quickly unhooked Simpson using his own universal handcuff key. As he did so, he noticed that the middle finger of Simpson’s left hand was bandaged.

The detective did not intend to arrest Simpson at that point in time. Once he was arrested, Vannatter knew he only had a maximum of 48 hours to file charges, which did not leave him or his partner enough time to complete their investigation, or to receive confirmation from the blood-analysis work that would indicate if Simpson really was the prime suspect.

It was important, however, to interview Simpson and, with the agreement of Howard Weitzman, they arranged to travel to downtown Los Angeles to the Parker Center headquarters of the LAPD. Enroute, Vannatter contacted his partner by cell phone and Lange agreed to leave South Bundy and meet them at the station. Lange logged out of the crime scene at 12:15 p.m. and drove straight to the police building at 150 North Los Angeles Street.

At the police headquarters, Simpson conferred with his lawyers. Skip Taft, another of Simpson’s personal attorneys, accompanied Weitzman. Taft had been part of the welcoming committee at LAX earlier in the morning when Simpson had returned from Chicago and had accompanied him to the Rockingham estate. To the amazement of the two police officers, Simpson’s attorneys were quite relaxed about the officers carrying out an interview with their client, even to the point of leaving Simpson and heading out to lunch.

At 1:35 p.m., the interview between Lange, Vannatter and O.J. Simpson began. It lasted exactly 37 minutes. The two detectives were later widely criticized for the manner in which they conducted the discussion with Simpson. But most observers overlooked the fact that their talk with Simpson was just that and not an official interrogation, which would have occurred if there had been hard evidence at that time linking Simpson to the murders. At that stage, the police had no real evidence and the detectives knew that at any time Simpson could have just gotten up and walked away. He was not under arrest and did not need to answer any questions unless he felt like it.

It was imperative to get Simpson to relax and talk: the more he talked, the more he might reveal. But they also desperately wanted to get a sample of his blood, get his permission to photograph the wound on his hand before it had time to heal and fingerprint him. All of this required his full cooperation and permission.

Through the course of the interview, the detectives learned nothing of major importance, although in their discussion, Simpson contradicted himself over a number of things. His timing on the use of the Ford Bronco, the way he injured his hand, the fact that he claimed to have been wearing tennis shoes earlier in the evening of the murders, when photographic evidence would subsequently prove otherwise. He claimed at one stage that he had been rushing in his pre-trip preparation; and then later that he was leisurely getting ready to go, chipping a few golf balls for relaxation on the lawn of his estate, late into the evening.

When the interview was over, the two detectives escorted Simpson to the Latent Print Unit in the building, where his fingerprints were taken. Following this they arranged for a photograph of his wound to be recorded and then guided Simpson to the medical dispensary in the jail that was located in the Parker building.

There, a sample of Simpson’s blood was drawn by a male nurse, Thano Peratis, and stored in a vial containing EDTA, an acronym for Trisodium Ethylenediaminetetraacetate Trihydrate, an amino acid preservative that is used to protect blood, among other substances, from rapid deterioration, or until it can be refrigerated. The vial was labelled and placed in an official LAPD evidence envelope.

Much would be made later of the amount of blood drawn from Simpson’s arm that afternoon. At a grand jury and preliminary hearing, Peratis claimed he drew and bottled about 8 cc’s. Because the LAPD/SID could only account for 6.5 cc’s, it was to be claimed by Simpson’s defense team that the difference, about one quarter of a teaspoon, had been used to plant evidence incriminating him in the two murders. In fact, Peratis never really knew just how much blood he had taken from Simpson. It was not officially recorded that day and his statement regarding 8cc’s was simply a best estimate on his part, based largely on the amounts he had generally taken in previous samplings.

The presence of EDTA in blood samples taken from the crime scene would also become a major and contentious issue between the defense and prosecuting teams in the murder trial that would evolve out of the police investigation.

The detectives returned to their office about 3:30 p.m. and Simpson left the building accompanied by his two lawyers. The officers reported to Captain Gartland, the officer in charge of the Robbery/Homicide Division. They were, by now, convinced that O.J. Simpson had killed his wife and Ronald Goldman.

While talking with their captain, they learned that a Chicago police detective had gone to the O’Hare Plaza Hotel and examined Room 915, which Simpson had occupied the night before. He had found a broken glass in the bathroom sink. Simpson had previously claimed to have cut his hand before leaving home for Chicago and then re-opened the wound when he cut it on the glass.

Lange and Vannatter left the Parker Center in their separate cars and headed back to Brentwood. Dennis Fung, the LAPD criminalist had shut down the South Bundy crime scene at 3:45 p.m. and returned to the Rockingham estate. It had now become apparent to Vannatter that the bloodstains and their analysis were crucial to the case and he needed to get the blood sample into the chain of evidence.

What he did next would come to haunt him in the months ahead, and his action would result in massive criticism of his work ethic and his involvement in a grand conspiracy to frame O.J. Simpson for the double murders by using blood from the vial to contaminate the crime scenes. In fact, his actions were based on the necessity to follow correct procedures and get the blood sample into the evidence chain as quickly as possible.

Within the LAPD a system is used to catalogue for record-keeping purposes, based on what is known as DR or Division of Records Number. The lead detective in an investigation gives details of his case to the Division in which the crime occurs. The detective is then allocated a DR number under which all record keeping is catalogued. At all times, reports circulating within an investigation must carry a DR number and nothing can be booked as evidence at the LAPD Property Division unless it is accompanied by the appropriate DR number. The Brown/Goldman murder inquiry would be allocated two numbers, one for each victim, although the investigation would be carried out using DR number 94-0817431, the one allocated to Nicole.

Dennis Fung, the criminalist, was responsible for the cataloguing, collection, and sequencing of evidence at both crime scenes. He had, in fact, booked the very first evidence that morning before 8:00 a.m., on the Ford Bronco. Before the blood taken from Simpson could be sent for analysis, it had to be catalogued by Dennis Fung.

Vannatter drove out back to Simpson’s home, arriving at 5:16 p.m. The two criminalists had by this time finished their work and collected all their samples at Rockingham Avenue and where preparing to leave.

Detective Vannatter handed the evidence envelope containing the vial of blood to Dennis Fung. It was in an 8 1/2 by 11-inch grey, blood collection envelope. Fung checked the contents and then wrote on the outside of the envelope,”Received from Vannatter on 6-13-94 at 17:20 hours.” He passed it over to his assistant, Mazzola, to put inside the LAPD’s crime scene truck. At that point, in accordance with state law, standard operating procedures and LAPD regulations, the chain of custody transferring the blood as evidence from Detective Phil Vannatter over to criminalist Dennis Fung was completed, by the book.

This was done in full view of reporters and the media film crews gathered around the Rockingham estate, who recorded on video tape the detective walking into the estate carrying the grey envelope, its actual transfer to Fung, and then Mazzola carrying it in a black evidence bag into the truck.

Simpson’s lawyers would make a big deal of this simple procedural action.

As Lange and Vannatter had been interviewing Simpson downtown, Fung and his assistant had been collecting evidence at Rockingham Avenue under the supervision of Detective Bert Luper, who had been monitoring the crime scene on behalf of the lead detectives.

Among the items found and tabulated was: “#13 socks, navy blue — recovered from the master bedroom.” Like the blanket used to cover Nicole’s body, the definition of Simpson as a potential rather than an actual suspect and the vial of blood handed over to Dennis Fung, the discovery of the socks would create yet another item of evidence tampering in the eyes of the Simpson defense team.

The LAPD routinely used video cameras to shoot scenes of premises entered under the service of a search warrant. This covered them against any future claims of impropriety and acted as a damage control moderator. LAPD/SID Photo Unit photographer Willie Ford videotaped Simpson’s house, including the master bedroom at 3:00 p.m. Earlier, Fung noticed the socks and bagged and collected them prior to when the video was shot. However, the clock on the camera had not been reset after a long period of inactivity and, as a consequence, the defense team claimed the socks had been planted there by the police. They became important items of evidence because, on analysis, they were found to be contaminated by blood, and a DNA test would show that the odds were one in 7.7 billion that the blood belonged to any one other than Nicole Brown Simpson.

The ring of evidence was closing tighter and tighter around O.J. Simpson for the brutal murder of the two people who had been drawn together on that quiet summer’s evening in Brentwood.

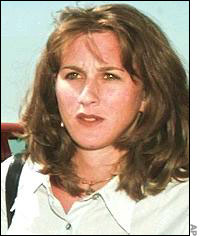

Nicole Brown Simpson was 35-years-old when she died. She was born on May 19, 1959 in Germany. She grew into a tall, willowy blonde beauty, almost the epitome of the Southern Californian beach belle. She was, according to a friend, “a very simple, very unsophisticated woman who had never prepared herself to live independently in the world. She had no job skills.”

She was working as a waitress in a Beverly Hills nightclub called “The Daisy” when she first came into contact with O.J. Simpson. She was 18; he was 30 and married with a family. Eight years later, he was divorced and on February 2, 1985, he and Nicole were married.

She moved into his palatial home in Brentwood on Rockingham Avenue and lived the good life, or so it seemed, until January 1992, when they parted and she and their children relocated to a rented property on Gretna Green Way, only a few hundred yards from South Bundy Drive. She subsequently filed for divorce, which became final on October 15th of that year.

As their marriage deteriorated, Simpson seemed to resort more and more to physical violence. One incident on New Year’s Eve, 1989 resulted in the police being called to the Rockingham Avenue home. Simpson was subsequently charged by the city attorney’s office, pleaded “no contest” to a charge of spousal battery, and was sentenced to 120 hours of community-service work and two years probation.

On October 25th, 1993, Nicole made a 911 call asking for police. In the background, the dispatcher could hear a man screaming and yelling, his words unintelligible. When police officers responded to Nicole’s home on Gretna Green Way, they found O.J. Simpson on the property. He had kicked in the french doors at the rear of the house. Nicole refused to press charges, but later that night, she told Sergeant Craig Lalley of the LAPD how frightened she was of Simpson and his moods, saying, “When O.J. gets this crazed, I get scared. He gets a very animalistic look in him… His eyes are black. I mean, cold, like an animal.”

O.J. Simpson had apparently been abusive to his new wife as early as 1985. Then pregnant with his first child, she had called the police. The responding officer, Mark Fuhrman, found that Simpson had attacked Nicole’s car (which he himself owned) with a baseball bat, but no charges were ever made by either Nicole or the police.

In fact, according to a diary that Nicole had kept, Simpson’s domestic violence began as early as 1977, and by the time of the murder trial in 1995, the Los Angeles prosecution had compiled a list of his abusive behavior which contained 62 separate incidents of physical and mental mistreatment, in addition to numerous threats and examples of control manipulation he had carried out.

Just why, in the end, the marriage collapsed has never been disclosed. In addition to the abuse, it may have been her distress at his philandering. One of Nicole’s friends, Robin Green, said in a police interview that the root of the problem in their marriage was his constant messing about with other women. Nicole apparently worried about his affairs and the fear that he might infect her with AIDS. When she confronted him with this knowledge, it would anger him and he would physically assault her during these arguments.

According to her therapist, Dr. Susan Forward, “Nicole was battered incessantly, regularly, all the time. I’m not saying 24 hours a day, but the incidents of battery were extraordinarily high.”

Nicole was no doubt deeply concerned by the level of physical abuse Simpson generated throughout their marriage and how far he might go one day. Her mother, Juditha, reported to the investigating police officers that her daughter had told her a month prior to the murders, Simpson had said, “If I ever see you with another man, I’ll kill you.”

It is possible that Nicole may have started to feel deprived of the kind of sexual experimentation many young people have after leaving high school. She had probably been limited by her early relationship with Simpson. After their break up she had a number of affairs, mostly casual.

During her stay at the Gretna Green house, she rented out a spare room to a young man she had met in Aspen, Colorado, called Brian Jerrad Kaelin, nicknamed ‘Kato.’ An aspiring actor, he functioned as an unpaid housekeeper and child minder. When Nicole bought the condominium on South Bundy and moved there in December 1993, she had offered Kaelin a room. Simpson, apparently concerned that Nicole was having a young man living at her new property, offered Kaelin a guest bungalow at his Rockingham estate.

On the afternoon of the murders, Nicole and her children, accompanied by the Brown family and some friends, had gone to a dance recital for Sydney at the Paul Revere Middle School in Brentwood. O.J. Simpson also attended, but sat apart and did not get involved with the other group.

Afterwards, Nicole and her party went at about 7:00 p.m. to the Mezzaluna Trattoria, a trendy Italian restaurant on San Vicente Boulevard in Brentwood. There Nicole introduced her group to a waiter called Ronald Goldman, a young man who modeled on the side and had dreams of being an actor someday. He would never realize this or any of the other goals he had set himself. A true victim of fate, he would find himself later in the evening in a murderous cul-de-sac from which there was no escape.

Born in Chicago in July 1968, he moved with his family to Los Angeles in 1987. There he blossomed from a shy young man into a happy extrovert who lived and loved the California lifestyle, excelling at tennis, surfing, playing volleyball and baseball with his friends, and training at the gym. He worked for a time taking care of cerebral palsy patients A close friend described him as, “One of the most loving, giving people that I have ever known.” His sister Kimberly said of him “My brother was a big-hearted, down-to-earth, hard working, goal-oriented person who wanted to get married, have a family and be successful.”

He was 20-years-old when he moved out of the family home, eventually winding up in Brentwood, where he loved the friendly atmosphere. In February 1994, to help pay the bills, he got a job at the trendy Mezzaluna as a waiter.

A few months before he died, he met Nicole and she let him drive her around in her white Ferrari, an experience he related to friends as “the coolest high” he had ever had. They had both been members of the Mark Steven’s Gym on San Vicente Boulevard, not far from the Mezzaluna restaurant, and although they were obviously good friends, it has never been suggested that they were more than that.

He had lots of friends, he loved his family; he was one of those people who was always there for others, and he ultimately died in that kind of role.

The Brown party finished dinner and left the restaurant at about 9:00 p.m. Nicole and her two children and another little girl friend of Sydney’s went across the street to a Ben and Jerry’s ice cream parlor. As Nicole was walking away, her mother, Juditha, remembered watching her go. “They were going across the street. I stopped for some reason and looked back at her again. I was thinking ‘What a gorgeous girl; what great legs.’ Those were my thoughts. That’s the last time I saw her alive.”

About 40 minutes later, Nicole’s mother rang the manager of the restaurant to say that she had misplaced a pair of eyeglasses. They were not in the dining room, but an employee found them outside in the gutter. After Juditha had contacted her at her home, Nicole then rang the Mezzaluna and spoke to Goldman. He agreed to drop around after he completed his shift and deliver the glasses to Nicole. Finishing work, he went to his apartment to change from his working clothes, and then drove down to Nicole’s condominium in a borrowed car, parking it on Dorothy Street, a few yards from the South Bundy address. It was found there, the next day.

And so Ronald Goldman became a statistic of fate. The odds against him dying the way he did were probably higher than him being struck by lightning. He was over six feet in height, fit and strong, an exponent of martial arts, and yet he was tossed around like a rag doll and eliminated by a killer possessed of more than just brute force. The man who slashed and stabbed Ronald Goldman to death and then calmly executed Nicole Brown was empowered with more than just physical strength. He was possessed by, and bursting with, adrenaline-fuelled rage, or some kind of anti-social madness that made him omnipotent.

The third key player in this drama, Orenthal James Simpson, was born on July 9th, 1947, at Stanford University Hospital near San Francisco, the son of Jimmie and Eunice Durden Simpson. He was two years old when he contracted rickets and had to wear braces on his legs until he reached five. At 13 he was a street gang member of the Persian Warriors and, in 1962 when he was 15, he spent time in custody at the San Francisco Youth Guidance Center. His father left his mother for another man and died of AIDS in 1986.

Simpson married at the age of eighteen his Galileo High School sweetheart, Marguerite White, and their first child, Aaron, was born on December 1968. Their second child, Arnelle, was born on April 21, 1970.

He became an All-American during both of his varsity seasons at USC and set a number of NCAA running records, closing out his undergraduate days by collecting the Heisman Trophy. He became a top class professional football player, spending most of his career with the Buffalo Bills, although he finished his professional career with the San Francisco 49ers.

He retired from professional football in 1979 and made a cameo appearance at the 1984 Olympic Games. In 1985 he was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame, crediting his mother with his success. She apparently responded, “I didn’t really think he’d turn out the way he did, but he always said you’d read about him in the papers someday and my oldest daughter would always say, ‘In the police reports.'”

Ten years later, he was doing both, with a vengeance.

By noon on June 14th, Dr Irwin Golden had carried out autopsies on the two murder victims. He had joined the coroner’s office in July 1980 and had carried out over 5,000 postmortems. He performed his investigations in the presence of the two lead detectives.

Nicole had received four deep penetration wounds,one of which was the slash across the neck that had almost decapitated her. She had also received a large contusion to the back of the head, which indicated blunt-force trauma. There were slash wounds to her hands, which showed that she had tried to defend herself against the attack. Judging by the details of the wounds, the pathologist determined that the attacker was probably right-handed and had slashed her throat from behind, from left to right.

Ronald Goldman also had a large contusion on the back of the head, which suggested he also might have been struck from behind by the attacker. There were six wounds found on his face and neck and several more on his body, a grand total of 19 in all. Some of the wounds intersected, indicating a frenzied attack; four of the lacerations were fatal penetration wounds.

The single set of bloody footprints leading away from the bodies argued in favor of there being one killer. The knife used to kill both victims had to have a blade that was at least six inches long. Later it was learned that Simpson had recently purchased a knife fitting that description.

At about 8:00 a.m. on June 15th, Detective Vannatter visited the coroner’s office and signed out the two vials of blood that had been taken from the victims and stored at the autopsy the previous day. He delivered them in person to the LAPD serology unit, which was to carry out the tests on the blood samples from the crime scene and Rockingham Avenue, and signed them over to Colin Yamauchi, a LAPD/SID blood specialist. The SID serology unit would carry out all the tests on blood samples except the RFLP tests. These were too complex for the unit to perform and would be farmed out to a specialized civilian testing agency.

The DNA testing of the blood would focus on the two major areas known as PCR and RFLP. The PCR method is generally used to eliminate suspects, whereas the RFLP, a much more definitive analysis can single out one person in a million or even a billion to the exclusion of everyone else in the world. Deoxyribonucleic acid or as it is more commonly known, DNA, is a genetic code material found within the cell nuclei of all living things. With the exception of identical twins, the complete DNA of each individual is unique and DNA fingerprinting or typing has been used in criminal and civil cases since 1988.

In the middle of the day, Lange and Vannatter met up with Los Angeles attorney Robert Shapiro who told them that he had taken over as Simpson’s lead attorney.

That afternoon, Allan W. Park, the limousine driver told police that he had been instructed to be at the Rockingham estate that night no later than 10:45. He got there about 20 minutes early. He tried repeatedly and unsuccessfully to make contact with the house using the gate telephone. At about 10:50 p.m. he saw a man in dark clothing hurrying up the drive towards the house from the Rockingham gate side of the estate. Shortly after, calling the house again on the gate phone, he made contact with a man who identified himself as Simpson, saying he had overslept and would be right down. When Simpson arrived he was sweating profusely and insisted on the air-conditioning being kept on all the way down to LAX.

This was critical information from an independent witness, who had clearly seen a man about six feet in height (Simpson was six feet-one inch), dressed in dark clothing, seemingly enter the property only minutes before Simpson himself answered the telephone which had gone unanswered for 20 minutes or so.

The lead detectives also received a telephone call from a neighbor of Nicole’s called Jill Shively. She claimed that on the Sunday evening as she was driving to a nearby market, she saw two vehicles almost collide at the intersection of San Vicente Boulevard and South Bundy. A white Ford Bronco came barreling north across the junction, driving through a red light and almost hitting another car traveling west down the boulevard. She recognized the Bronco driver as O.J. Simpson, timing the near accident at about 11:00 p.m. Shively was a local and had seen both Nicole and Simpson in the neighborhood many times.

Although she subsequently gave her evidence before a grand jury on June 21st, she impeached herself as a witness by lying as to whether or not she had discussed the incident with anyone. She claimed only her family, but in fact, that night she appeared on a tabloid television show to discuss it and was paid $5,000. As a result, the prosecution refused to call her as a witness.

On Thursday, June 16th, preliminary DNA test results on the glove found at the Rockingham estate confirmed that the blood was Simpson’s and both of the victims. It needed confirmation by the complex RFLP tests that were a long way off at that time, but it was expected that these additional tests would confirm their first analysis.

That evening, Vannatter and Lange reviewed the evidence they had collected with Captain William O. Gartland and Lieutenant John Rogers. It all pointed to Simpson as the killer. Later,they filed a formal complaint.

Earlier in the day, Nicole Brown had been buried by her family and friends in Lake Forest Cemetery, Mission Viejo, in Orange County about 45 miles south of downtown Los Angeles. Juditha Brown later recalled how on the day before at a wake held for Nicole, O.J. Simpson had leant over his ex-wife’s open coffin, kissed her on the lips and murmured, ” I’m so sorry, Nicki, I’m so sorry.”

The next morning, Lange, Vannatter and Marcia Clark prepared a four-page arrest warrant, which was checked and approved by the District Attorney, Gil Garcetti. Then Tom Lange telephoned Robert Shapiro and instructed him to accompany his client to the Parker Center to surrender at 11:00 a.m., failing which the detectives would come and arrest him. Simpson was staying at the home of Robert Kardashian in the San Fernando Valley. He had gone there after attending the funeral of Nicole.

By 12:35 p.m., Simpson and his lawyer had not turned up so three patrol cars were sent to Kardashian’s to get him. The police learned that Simpson had left with his close friend Al Cowling in a white Ford Bronco.

At 2:00 p.m., Commander David Gascon, the LAPD’s official spokesperson, held a press conference at the Parker Center, announcing that a warrant had been issued for the arrest of O.J. Simpson, who was on the run and being sought as a fugitive.

At 5:00 p.m., that evening, Robert Shapiro made an appeal on television to Simpson, asking him to surrender immediately. Robert Kardashian, who read out what seemed to be a suicide note, written earlier in the day by Simpson, followed Shapiro. It was long, rambling, sentimental and morose, and proclaimed his innocence.

By now, the LAPD had received confirmation through traced cellular phone messages that Cowling and Simpson were traveling somewhere in Orange County. At about 6:45 p.m., an Orange County Sheriff’s deputy spotted the Ford Bronco driving north on Intersate Five. Although ordered to pull over and stop, Cowling kept rolling, but switched on his hazard lights and slowed down to a sedate 40 miles an hour. At about that point, Cowling dialed 911 on his cellular phone and told the police to back off as Simpson was suicidal and had a gun to his head.

By this time, the media had been alerted and the sky above the Ford Bronco filled up with helicopters carrying television camera crews and reporters, as well as the law enforcement ones. The slow-speed chase became the most widely watched impromptu event in American television history. The only event that came close to matching it in the last 50 years was the moon landing.

There were so many choppers buzzing around, it looked like a scene from a war movie. At one time, a Channel 7 helicopter had to break to refuel and the station had to link into a competitor’s coverage to maintain its spontaneity. As a result, people watching the Channel 7 news were confronted with the Channel 5 logo on their screens.

Crowds of spectators, alerted by the television coverage and the radio airwaves that literally crackled with the news, gathered along the freeway and crowded out the overhead bridges, shouting and cheering as though they were watching some July 4th, parade. The slow speed chase developed all the trademarks of a carnival or circus performance, a harbinger of what lay ahead in the months to follow.

As the convoy proceeded north up the 405 Freeway, Cowling requested that he be allowed to go straight to Simpson’s home on Rockingham Avenue. Captain William O. Gartland, head of the Robbery/Homicide Division, agreed to the request and then ordered the LAPD Metro Division to dispatch its negotiation and SWAT teams to converge on the estate and secure the perimeter.

By now, the cavalcade had crossed the borderline into the city of Los Angeles and, although LAPD helicopters assumed the air space, the Orange County patrol cars continued on with the chase, now under the control of the LAPD black-and-whites.

The Bronco headed north, passing LAX, and left the freeway at the Sunset Boulevard exit ramp. Swinging left across the freeway, it headed west towards the Pacific Ocean until it reached Rockingham Avenue. At approximately 7:50 p.m., the long, slow, maniacal journey came to an end as Al Cowling pulled into the driveway of Simpson’s home and switched off the engine.

Here gathered, as a welcoming committee, was a small army of police officers. Twenty-seven members of the LAPD SWAT unit, a vehicle assault team, a full element of Metro specialists, and a two-man negotiating team headed by Officer Peter Weireter. Above, fluttering about like demented mechanical moths, were the helicopters of the media assault teams trying to get the definitive landscape montage on record for their rapacious audiences, who were glued to their television screens across the nation and the world.

Almost an hour later at 8:45 p.m., after non-stop pleading and cajoling by Cowling and the negotiating team, Simpson finally emerged from the Bronco and surrendered. The chase was over, but the hunt for justice was just beginning.

“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers…”

— William Shakespeare, Henry VI, Part III

Orenthal James Simpson was arrested on June 17, 1994. He would not go on trial for the double murders until January 25, 1995.

He and his best friend, Al ‘A little help from my friends’ Cowling, were taken downtown to the Parker Center and processed late in the evening. In the Ford Bronco, detectives had found a travel bag containing among other things, Simpson’s passport, a disguise kit consisting of a fake moustache and beard and a .357 magnum revolver. Cowling was also found to be carrying $8,000 in cash, which had been given to him by Simpson. Two days later, Simpson pleaded not guilty when arraigned and was remanded to the Los Angeles County jail.

Here, he would spend the next 15 months in a nine-by-seven foot prison cell located in a ward that would have him as its only inmate. Outside his cell was a common room in which there was furniture, a television set, plenty of sports magazines and newspapers and a pay telephone. Although he was a prisoner on remand for two brutal, heinous murders, it seemed that almost from day one, O.J. Simpson was not to be treated as your normal, average, every day suspected killer.

On this same day, Superior Court Supervising Judge Cecil J. Mills, announced that the man selected to preside over the case would be Judge Lance A. Ito. The small, elfin man, with a moon pie face, piercing dark eyes and a nervous, quirky mouth above a black beard, was married to the highest ranking female LAPD officer, Captain Peggy York, head of the Internal Affairs Division. Along with one of her former partners, Helen Kidder, Peggy York had served as inspiration for the lead characters in the long running television series, Cagney and Lacey.

Lance Ito was the son of Japanese-American parents who were interned during World War Two. In his teenage years, he was known as somewhat irreverent, decorating his room with Playboy centerfolds and driving a hot Boss 302 Mustang. He was also known to humorously celebrate Pearl Harbor Day by wearing an aviator’s helmet and cape and run through his campus hall shouting out “Banzai.”

His appointment by California’s governor to the bench in 1989 was seen as a wise political choice, partly because of his Asian heritage. But Ito, as the presiding judge in the Simpson trial, would turn out to be a man not in control of his emotions and who would allow sentimentalism to dictate his decisions.

By this time, Robert Shapiro and a team he was collecting around him were now heading O.J. Simpson’s defense. The first two were F. Lee. Bailey and Alan Dershowitz. Johnnie L. Cochran, a high profile, stylish Los Angeles lawyer who drove around in a Rolls Royce and had once worked in the Los Angeles district attorney’s office, followed them soon after the preliminary hearing.

Gerald Uleman, Robert Kardashian, Carl Douglas, Skip Taft, Robert Blazier joined these three in due course, and two who became known as the DNA Twins — Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, New York attorneys who specialized in DNA testimony. They were all highly paid, high profile, strong-willed characters that would find themselves referred to as the ‘Dream Team.’ At least five other attorneys and numerous back-up staff supported them.

According to Christopher Darden, the assistant prosecutor in the trial, the only thing the members of the ‘Dream Team’ seemed to have in common was a penchant for defending rich people and the ability to create publicity. Lead detectives Lange and Vannatter had a more jaundiced view of the group. They referred to them as the ‘Rat Patrol.’ To the police and prosecution counsels, the ‘Dream Team’ was often slack on logic, but slick on innuendo.

The ‘Dream Team’ designation came, of course, from the media who has a habit of framing titles to suit situations, irrespective of their veracity. It was costing Simpson thousands of dollars a week in fact to be defended by a bunch of lawyers, some of whom had limited or no experience in murder trials.

Shapiro had never tried a murder case before; Cochran was primarily a civil lawyer and had little, if any, success in defending clients in murder cases. The well-known F. Lee Bailey’s last stab at fame had been 20 years earlier when he had defended Patti Hearst in her famous and high profile bank robbery case involving the SLA, but he had dunked that one, and it had sent his career into serious decline. Alan Dershowitz was a distinguished law professional, but in the area of appellate law and not criminal or trial law.

Lined up against the defense team was the group representing the people of California.

The lead prosecutor was Marcia Clark, aged 41. Born in Berkley, California, she had graduated from University of California, Los Angeles in 1974 and earned a law degree in 1979 from South Western University. She had worked for two years as a criminal defense lawyer before joining the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office in 1981. There, she had handled 60 trials by jury, including 20 murder cases. She had spent four years in the Special Trials Unit, which handled the most complex and sensitive investigations.

While traveling in Europe as a teenager she had been attacked and raped. She had also been emotionally abused by her first husband and was fighting a bitter and acrimonious custody case with her second ex-husband over custody of their two children.

She had developed a reputation as a tough, hard and determined litigator who operated with drive and single-mindedness. She was the original prosecutor assigned to the case along with David Conn, an Assistant District Attorney in the Special Trials Unit, who was also at the time a lead prosecutor in the high-profile Menendez brothers murder trial. He was pulled off that case and assigned to the Simpson inquiry, but after a few weeks returned to his original case and was replaced by Bill Hodgman, Deputy District Attorney and head of the Special Trials Division. Hodgman had successfully prosecuted the savings and loan fraud case against Charles H. Keating in 1991. He was highly respected for his legal and diplomatic skills by lawyers and police.

Christopher Darden was a Grade Four veteran Assistant District Attorney who had tried 19 murder cases without an acquittal before he found himself immersed in the Simpson case. He was born on April 7th, 1956 in Richmond, across the bay from San Francisco. He had spent 14 years at the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office when Marcia Clark brought him in, initially to handle the investigation of Al Cowling.

These were to be the key players for the prosecution, backed up by at least another ten lawyers and support staff. Vincent Bugliosi, the man who successfully prosecuted the Manson Family, had little respect for them, calling the prosecution the most incompetent criminal prosecution he had ever seen.

Dershowitz had little praise for them either. In a television interview he said, “In 35 years of practicing law, I never encountered two more incompetent bunglers than Clark and Darden.” He claimed that he had heard Clark whispering to another lawyer in the courtroom, “I want you to remember I’m not wearing any underwear.” Added Dershowitz, “And that was one of her better moments.”

For the hosts of people who believe lawyers are the lowest form of life, the Simpson trial only seemed to reinforce this perception, and to many, the trial became an exercise in chicanery, deceit and egomania, with lawyers to the left and lawyers to the right all fighting to be number one in the spotlight. The ‘Dream Team’ turned into a nightmare. By the end of the trial, Cochran had called Shapiro hypocritical; Shapiro had vowed never to work again with Cochran; Bailey had accused Shapiro of being “a sick little puppy,” and Shapiro referred to Bailey as a “snake in the bed.”

They all of course, had to overcome the most powerful lawyer in court, Judge Ito, who many believed, allowed his robe to go to his head. Christopher Darden stated, “Judge Ito gave the defense the keys to the courtroom. He surrendered his gavel. Johnnie Cochran ran that courtroom, not Judge Ito.” Bugliosi thought, “Judge Ito displayed little common sense and specialized in making patently erroneous rulings, one after another.”

And so the lawyers and their assistants gathered, their cellular phones chirping and laptop’s humming, and the maneuvering began to stage the grand event that would hold, captivate and, in many instances, sicken, the American people for months to come. The Cirque du Soleil of the legal calendar was shaping up and it would indeed be a grand circus.

To the prosecution, the case was relatively simple and supported by “a mountain of evidence”: Simpson had an abusive relationship with Nicole; was jealous of her since their marriage break-up; had purchased a knife similar in size and shape to the murder weapon. Simpson dropped the bloody gloves, one at the crime scene and one at his home. He wore shoes the same size as the footprints leading away from the crime scene. His blood was everywhere, some of it mixed in with that of the victims. He had a motive; he had the opportunity; he had no alibi for the timeframe of the murders.

To the defense the case was even simpler. Their client was innocent, framed by unscrupulous, devious, lying police officers, aided and abetted by incompetent law enforcement officials and county technicians. The defense lawyers painted Simpson as yet another black victim of the white judicial system. He was on trial because he was a black man, being framed and set up by a white man’s legal system.

But O.J. Simpson was an unlikely symbol of the racial divide between black and white America. He married a white woman and made his high-priced living in the white man’s world, doing business with them, playing golf with them and socializing with them. Rather than appearing as a true representative of the black people, he more typified the division between the rich and the poor, showing just how easily money could buy justice.

The Grand Master of the Ring, Gil Garcetti, the District Attorney of Los Angeles, started the circus off by formulating a mystical and breath-taking non sequitur decision that would in essence chart the future of the trial before it even began.

“A jury consists of 12 persons chosen to decide who has the better lawyer.”

— attributed to Robert Frost

It is standard practice in Los Angeles County to file a case in the superior court of the judicial district in which the crime occurred. This was Santa Monica in the case of the Brown and Goldman murders. Instead, Garcetti made the decision to file the case downtown. He claimed this was because Special Trials were located there and that Santa Monica didn’t have the physical facilities to manage a trial of the kind envisaged. He also wanted it downtown to get the indictment of Simpson through a grand jury instead of the more commonly used preliminary hearing method, by which 99.9% of criminal cases in Los Angeles go to superior court.

The grand jury route would have been of strategic advantage to the prosecutor because these proceedings are secret and the defense does not participate, allowing the prosecution to secure its indictment without revealing the basis of its case to the defense prior to the trial. There is only one grand jury in Los Angeles and it is only convened downtown. However, the defense succeeded in getting the grand jury dismissed on the grounds that it had been tainted by the adverse publicity surrounding the case.

Had the case been held in Santa Monica, it is almost certain that the composition of the jury would have finished up being mainly white people. Had a jury of this ethnic mix found Simpson guilty, there was always the possibility of a major backlash from non-whites. The last major race riot in Los Angeles occurred when a largely white jury acquitted white policemen accused in the infamous Rodney King case. A similar verdict in reverse might well have triggered off another race riot.

Garcetti is also claimed to have said that a guilty verdict by a downtown jury would have had more credibility with the black community. It’s possible also that he thought the case was so airtight that his prosecutors couldn’t fail wherever they tried it. He could have been more wrong, but it’s hard to see how.

In the months leading up to the trial, it became obvious that the defense strategy would be based on developing evidence that the police had framed their client. They began with Det. Mark Fuhrman.

On July 25th, an article by Jeffrey R. Toobin appeared in The New Yorker magazine suggesting that the LAPD detective who had testified in the preliminary hearing about discovering the glove at Simpson’s estate had, in fact, planted it there. The article also referred to a disturbing pattern of behavior displayed by the detective in the past and his strong racist views. The author of the article had apparently based a lot of it on conversations he had with Robert Shapiro.

To the lead detectives on the case, the thought that Fuhrman could have planted the glove was laughable. He had, in fact, been the 17th police officer to login at the crime scene, almost two hours after the arrival of patrolmen Riske and Terrazas. Many other officers had viewed the crime scene and not one had seen or reported more than the one glove found near the bodies.

On August 18th, the defense filed a motion to obtain the personnel records of Detective Fuhrman.

The lead detectives, under questioning by Shapiro at the preliminary hearing, were accused of violating Simpson’s Fourth Amendment rights by entering his premises illegally. The detectives stressed that at the time, they entered the estate because they were concerned for his safety, not because he had become an actual suspect, because he was not.

On Friday, September 9th, Gil Garcetti announced that he would not seek the death penalty in the Simpson case. Although the murders were savage and bloodthirsty, they did not fall under the parameters that required the ultimate retribution by the state.

On September 21st, defense attorneys claimed in a pre-trial challenge that the original search warrant was inaccurately filed, hoping that if successful, all the evidence collected there would be ruled inadmissible. Although Judge Ito issued a scathing indictment against the way the search warrant had been compiled by Detective Phil Vannatter, claiming the detective’s actions were “negligent and reckless,” he nevertheless upheld the warrant and admitted the challenged evidence.

In fact Judge Ito’s acerbic criticism of the detectives’ procedural conduct was in itself negligent and reckless and was a classic example of the judge’s sometimes bizarre judicial behavior.In his search warrant, Vannatter had made only one assumption that was incorrect, two others that were true but unconfirmed at the time and one omission of fact: Vannatter had written that Simpson’s trip to Chicago was “unexpected.” In fact, it had been scheduled for some time. However, Vannatter had based his conclusion on Kato Kaelin deferring to Arnelle Simpson when they first contacted him during the early-morning hours of June 13th, asking for Simpson’s whereabouts. Arnelle initially said that she believed her father was in his house. As a result of the statements of both Kaelin and Simpson’s daughter, Vannatter believed that Simpson’s trip to Chicago was “unexpected.”

Also in his warrant Vannatter omitted that Simpson had voluntarily agreed to return to Los Angeles. However, unlike Lange and Phillips, he had not been party to the phone calls with Simpson at North Rockingham when the notification of his ex-wife’s death was made. In the midst of everything that was going on during those early-morning hours on June 13th, neither Lange nor Phillips had explained to him that Simpson had volunteered to leave Chicago, as opposed to being ordered by the detectives to return to Los Angeles.

The other mistake Vannatter had made was his premature identification of red spots on the driveway and the red substance on the right-hand glove as blood. Even though Dennis Fung later confirmed this as blood evidence, Vannatter had made these claims in his search warrant without that confirmation, relying instead on his observations from years of experience dealing with blood at crime scenes.

Commenting from the bench — even though there was no evidence of malice on Vannatter’s part or that he had deliberately lied — Judge Ito charges, “I cannot make a finding that this was merely negligent. I have to make a finding that this was reckless.” Nevertheless, Ito upheld that the search that was based on Vannatter’s supposedly “reckless” warrant was admissible.

By the end of September, evidence was mounting that the defense team was going to charge that not just Fuhrman, but other members of the LAPD, had also planted evidence at both crime scenes. The head of detectives, Commander John White, received information that the Simpson team had passed on to Time magazine rumors that the police were deeply involved in framing their client.

On September 26th, the defense demanded hair samples from the lead detectives and Fuhrman, as well as a search of the clothing they wore on the day of the investigation and the vehicles they drove. They also asked for photographs of their shoe soles to determine whether one of them had left the bloody footprints at South Bundy. This action was unheard of in Los Angeles police procedure and to rub salt into the wound, on Wednesday October 5th, Gerald Uelman accused the detectives of a “well-orchestrated ticket of lies” and false testimony.

By November 8th, a jury had been selected to hear the case. It consisted of eight African-Americans, two of mixed descent, one Hispanic and one white. The alternate jury was made up of seven African-Americans, one Hispanic and four white people. By the end of the trial, only six of the original jury would still be serving. The foreperson was Juror #230, Armanda Cooley.

Newsweek on September 30th, 1996 wrote: “prosecutors lost the criminal trial virtually the day the predominantly African-American jury was sworn in.”

The New Year came in on a rainy, miserable Monday, January 9th. The jury was gathered together and informed that they were to be sequestered from Wednesday January 11th until the trial was completed. They were to be in this kind of limbo-land for 267 days, returning after the trial each evening to the fifth floor of the Hotel Inter-Continental at 251 South Olive Street, about half a mile from the Superior Court building on West Temple Street.

It was the middle of winter when the jury gathered for the first time in Department 103 on the ninth floor of the courts building where the trial was held. They would sit and listen to evidence as the year turned into spring, moving through summer and into fall, before the trial came to an end in the first week of October. The jury became part of a judicial mosaic that held the world’s fascinated attention through the hysteria and hype that would surround it, over the months of 1995.

In 1841, Charles Mackay wrote a book called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. A Victorian classic about grand-scale madness and the universal human susceptibility to manias and deceptions, it is best remembered for its accounts of many financial bubbles, including the craze known as “tulipmania,” which seized Holland in the 16th century. Wealthy Dutch aristocrats sank entire fortunes, everything they had, into one single tulip bulb, which sometimes sold for the equivalent of $150,000 to $1,5000,000 for the most sought after bulb of all, known as the Semper Augustus bulb. The most priceless things imaginable at the time. Until one day, when somebody realized that after all, they were just flowers, and the whole manifestation collapsed.