Adventures of Larry Flynt — Hot Poker Through the Midsection — Crime Library

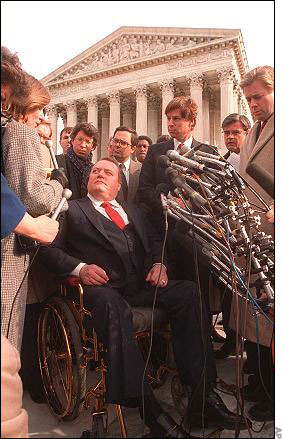

On the morning of Monday, March 6, 1978, Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt arrived with his lawyers at the courthouse in Lawrenceville, Georgia, to face obscenity charges. It wasn’t his first run-in with the law regarding the illegal distribution of pornography, so he knew the drill. He also felt that Jesus was on his side because in the last year he had become an evangelical Christian under the ministry of Ruth Carter Stapleton, the sister of Jimmy Carter, who was then President of the United States. Flynt and Stapleton had become close friends that year.

When court proceedings recessed for lunch, Flynt and his attorneys, Gene Reeves and Paul Cambria, walked to a nearby restaurant, the V&J Cafeteria, where Flynt ordered two glasses of grapefruit juice. His friend, comedian and political activist Dick Gregory, had recently encouraged him to become a vegetarian and had helped him lose 25 pounds, and Flynt was fasting to maintain his good health.

After lunch the three men strolled back to the courthouse. As they turned onto the sidewalk that led to the courthouse, a gunshot suddenly rang out. Flynt turned toward Reeves just as a bullet pierced the attorney’s arm. Reeves collapsed, and a second shot was fired. Flynt felt as if a “hot poker” had seared through his midsection. He says in his autobiography, An Unseemly Man, when he looked down, he saw his intestines hanging out. A .44 Magnum bullet had entered at an “odd angle” and in his words, “nearly ripped the front of my stomach off.”

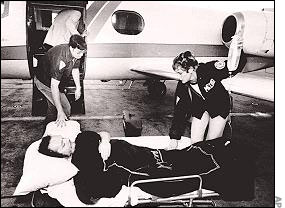

His abdominal artery had been severed, and he was bleeding out. Paramedics rushed him to the hospital where doctors removed six feet of his intestines and did their best to stop the internal bleeding, but there was one leak they couldn’t locate. Flynt was given continuous transfusions, but his doctors knew he couldn’t survive for long like that. A medevac helicopter took him to a larger facility, Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, where he endured 11 surgeries to find the leak. Finally a CAT scan, which was relatively new to medical technology at the time, pinpointed the problem. A piece of shrapnel had nicked an artery one-half inch from his heart. The doctors succeeded in repairing the damage, but Flynt’s problems were just beginning.

The bullet had damaged a collection of nerves at the base of his spine, leaving his legs paralyzed but in excruciating pain. If the slug had severed his spine, he would have still been paralyzed but pain free. The pain was unremitting, leaving him feeling as if he were “suspended in a vat of boiling water.”

Unable to accept a God who could allow such merciless torment, Flynt renounced Christianity and relocated to Los Angeles where he bought a mansion that had been built by actor Errol Flynn, and at various times had been the home of actor Robert Stack, actor Tony Curtis, and Sonny and Cher while they were married. In his never-ending quest to get some relief from his pain, Flynt became a drug addict, taking a concoction prescribed for terminally ill cancer patients called a “Brompton Cocktail,” which consisted of “60 percent morphine, 30 percent pharmaceutical grade cocaine, and 10 percent alcohol mixed into a mint-flavored syrup base.” He had also been prescribed every major pain-killing medication on the market and as a result overdosed regularly. But his heart was strong, and he always managed to survive. Perhaps what kept him going was his dedication to the two things in life that mattered most to him: the First Amendment and pornography. These twin passions have given Larry Flynt a unique position in the annals of American criminal justice: he has been a celebrated criminal as well as a celebrated victim of crime.

Larry Flynt’s sexual odyssey began when, at the age of nine, he had intercourse with one of his grandmother’s chickens. Older boys had told him that the sensation would be similar to being with a woman, but the experience left him unconvinced. Fearing that his grandmother would discover the damaged bird and figure out what he’d done, he wrung its neck and threw it in the creek.

Flynt was born in Lakeville, Kentucky, in 1942. His childhood was marred by poverty, his father’s absence while serving in the Army during World War II, then his father’s alcoholism when he returned. His parents divorced when Larry was ten, and he moved to Indiana with his mother. At the age of 15, he lied about his age and enlisted in the Army, but because it was peacetime, he was discharged in less than a year. Unable to find a good job, he enlisted in the Navy in 1959 and attended Radar A School. He was eventually assigned to the Combat Information Center aboard the USS Enterprise, America’s first nuclear-powered surface warship. It was a plum position, with 95 sailors under his command; Flynt was just shy of his 20th birthday.

After his stint in the Navy, Flynt bought a bar that his mother owned and operated in Dayton, Ohio. He changed the name from the Keewee to the Hillbilly Haven to appeal to the blue-collar workers who had migrated to the factories of Ohio from rural Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia. He knew his market and did good business, eventually buying several more bars in the area. When he heard about “go-go bars,” which were prospering on the West Coast, he decided to open the first one in the East. Flynt had a feeling the concept would go over well in Dayton. Women in mini-skirts and white go-go boots would dance on the bar, and for $100, a customer could get the girl of his choice to remove her top and show her breasts. He decided to call his first go-go bar the Hustler Club. Between 1968 and 1971, he opened other Hustler Clubs in Cleveland, Cincinnati, Columbus, Akron, and Toledo.

Kennedy Onassis

Hustler magazine, which would become the tent pole of his sex empire, started as a newsletter for his club customers. The newsletter proved to be so popular that Flynt decided to transform it into a glossy magazine. The first issue was published in July 1974. True to Flynt’s hillbilly aesthetics, the nude photographs presented in Hustler were raunchy and more graphic than those of its competitors. Unlike the airbrushed, anatomically perfect women in Playboy or the artistically posed models in Penthouse, the women who posed for Hustler were meant to be the kind of girls a man might pick up at one of Flynt’s establishments. Flynt wanted his nudes to look just like real one-night stands, displaying frank shots of female genitalia.

The magazine was not an overnight success, but as each succeeding issue became more and more audacious, the audience gradually grew. Then in August 1975, Flynt shocked and outraged the nation when Hustler ran a five-page pictorial of former first lady, Jackie Kennedy Onassis, caught sunbathing nude by paparazzi. Circulation soared, eventually reaching 3 million. With a high cover price, for the time, of $2.25, the hillbilly hustler from the backwoods of Kentucky was now the prince of porn, sitting on a gold mine.

In 1973, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Miller v. California that a national consensus on what is obscene was no longer necessary to get a conviction in any local jurisdiction. Individual communities could set the standards for what was obscene and objectionable, and prosecutors did not have to offer proof of any kind as to what made a book, magazine, or film obscene. The ultra-conservative Citizens for Decency Through Law, led by Charles H. Keating, Jr. (who would later go to prison for fraud and racketeering in the much-publicized Lincoln Savings and Loan scandal), put Larry Flynt in their crosshairs, and in 1976 got local prosecutors to charge Flynt with obscenity, pandering, and organized crime for the distribution of Hustler in Hamilton County, Ohio. Flynt had no doubts that the judge and prosecutors were determined to throw the book at him.

In his dramatic summation at the trial, lead prosecutor Simon Leis took a piece of chalk out of his pocket and traced a line across the courtroom floor. “It’s time to draw the line against obscenity,” he declared.

Not surprisingly, Flynt was found guilty on all counts, handcuffed on the spot, and brought before the judge for immediate sentencing. Flynt asked if he could address the court, and the judge complied. Flynt was so angry he couldn’t contain himself. “You haven’t made an intelligent decision during the course of this trial,” he fumed at the judge, “and I don’t expect one now.”

The judge responded by giving him the maximum sentence — seven to 25 years in prison without bond and $11,000 in fines.

Flynt was thrown in jail, but his attorneys filed for appeal and managed to get him out on bond after serving just six days. The conviction was eventually overturned on a technicality.

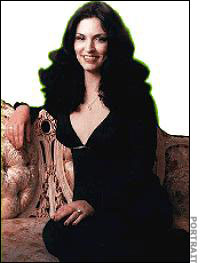

While fighting for his freedom in court, Flynt married his fourth wife, 24-year-old Althea Leasure, who had appeared in Hustler as the July 1975 centerfold and worked her way up to editorial director of the magazine. After a series of unsuccessful relationships, Flynt finally found the love of his life in the bisexual Leasure.

That same year, Flynt formed an unlikely alliance with evangelist Ruth Carter Stapleton. Initially drawn together by their mutual objection to child abuse, Stapleton soon became Flynt’s close personal adviser, bringing him into her fold of born-again Christians. For his part, Flynt gave Stapleton a first-hand look at the world of pornography and underground sex so that she would know first-hand what she was preaching against. For a brief period, Flynt seemed ready to repent and turn over a new leaf, declaring that he was “bored with pornography.” According to author John Heidenry, “Flynt vowed to turn his magazine toward a healthier vision of sex and religion.” But Flynt’s flirtation with Christianity was brief: it ended as he lay suffering excruciating pain from his gunshot wound.

Flynt, permanently crippled and confined to a wheelchair, lived for many years in unimaginable pain. Constantly searching for a drug that would give him some relief, he became addicted and frequently overdosed. His wife Althea also became addicted, unable to resist the lure of readily available legal and illegal narcotics. Flynt lived in a haze of pain and drugs, but with the help of his lifelong partner, his younger brother Jimmy, he continued to publish Hustler, which became increasingly audacious, breaking new ground in the area of men’s magazines. At various times, Hustler published a life-size naked foldout, a photo spread of pregnant women engaged in lesbian sex, photos of a hermaphrodite, and a scratch’n’sniff centerfold. Nothing was too tasteless for Hustler. A cartoon in the magazine once used First Lady Betty Ford’s mastectomy as the butt of a joke. Castration, dismemberment, scatology and bestiality were commonly represented in the pages of the magazine.

Flynt’s physical suffering seemed to fuel his fervor for First Amendment rights. In his autobiography, Flynt makes the distinction between pornography and obscenity. Photographs that are sexual in nature are not automatically obscene, he argues, and those who say so in fact fear and revile sex.

Beginning in 1983, Flynt was hauled into court on several occasions, and in many instances he managed to turn the cases into a First Amendment tests through his courtroom antics. A case that had been dogging him since 1976 came to a head in 1983, taking Flynt all the way to the Supreme Court. Kathy Keeton, the girlfriend of Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione, sued Flynt for printing a cartoon suggesting that she had contracted a venereal disease from Guccione. Guccione filed a separate suit for another Hustler cartoon that portrayed him having sex with another man. Guccione filed his case in Ohio and won a $39.6 million judgment against Hustler, which was later overturned on appeal. Keeton filed her case in New Hampshire, but the state dismissed her case, saying they had no jurisdiction in the matter, so she appealed to the Supreme Court. Flynt emerged from his “pain-filled, reclusive state of mind” and decided to represent himself in the highest court in the land.

The court appointed an attorney to represent him against his wishes. He asked if he could speak on his own behalf, but they refused to hear him. Fuming in the gallery, Flynt felt that he was being denied his constitutional right to defend himself. He shouted at the justices, “You’re nothing but eight assholes and a token cunt!”

Chief Justice Warren Burger pointed at him and shouted, “Arrest that man!”

The bailiff wheeled Flynt out of the courtroom, but no one could recall anyone ever having been arrested for contempt of the Supreme Court, and they weren’t sure what to do with him. Matters were complicated by the fact that Flynt needed to urinate, and Supreme Court restrooms were not equipped for the handicapped. After a side trip to a nearby hospital where Flynt was able to relieve himself, he was taken to a local courthouse for arraignment. While waiting in a holding cell, he took off his shirt to expose the tee shirt he wore underneath. He had written in block letters across the front: F*** THIS COURT. After a great deal of heated argument with the marshals, Flynt went into court wearing the tee shirt. The judge made no comment and quickly read the charge against him and set bail.

Flynt’s attorney, Alan Isaacman, who represented him in most of his cases, had the case moved to California and promised to subpoena all nine Supreme Court justices as witnesses. The Supreme Court eventually sent the Keeton case back to New Hampshire state court, where it “languished for years.”

In his autobiography, Flynt explains how he obtained embarrassing evidence of FBI entrapment. Hustler readers had gotten into the habit of sending him unsolicited videotapes and photographs of “the rich, famous, and infamous in flagrante delicto,” and by his own admission, he took delight in publishing some of this material in his magazine to humiliate public figures, especially right-wing politicians. But in 1983, he received an unusual videotape sent anonymously from the offices of the attorneys representing carmaker John DeLorean.

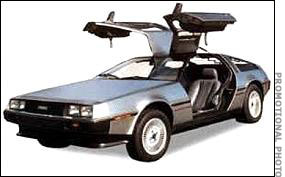

DeLorean had designed a state-of-the-art luxury automobile, which he had named after himself, and was desperately trying to get a piece of the market. The DeLorean was a distinctive-looking vehicle with a brushed steel exterior — a DeLorean body was used for the fictional time-travel machine in the Back to the Future movies — but the car did not catch on with the public, and the company was soon hemorrhaging money. Determined to salvage his dream, John DeLorean appeared to be willing to take desperate measures, and the FBI arrested him for possession of cocaine in dealer quantity. Allegedly, DeLorean hoped to use drug profits to keep his business afloat.

But the surveillance tape that Larry Flynt received showed DeLorean’s arrest and the events that preceded it. An undercover FBI agent posing as a dealer had offered the cocaine to DeLorean, suggesting to him that this would be a solution to his financial problems.

It was clearly a case of entrapment, and Flynt, the political firebrand, was determined to show the nation how far its government would go to make a high-profile arrest. He showed the tape to 60 Minutes producer Don Hewitt, who agreed to air it. The government sought an injunction to stop CBS from broadcasting the tape, but they failed, and the tape was shown, causing a national brouhaha.

In the meantime, Flynt came into possession of an audiotape of DeLorean’s entrapment. (In his book, Flynt does not explain how he received this one.) On this barely audible tape, DeLorean is heard trying to back out of the drug deal, but the undercover agent threatens to hurt his daughter if he reneges. Flynt called a press conference on the lawn of his California mansion to play the tape for reporters. He claims that in his drug-addled state he lost track of the tape and it disappeared that day.

The judge assigned to the DeLorean case, Robert Takasugi, subpoenaed Flynt to appear in court with the tape. Feeling ornery because of his constant pain, Flynt deliberately ignored the subpoena and was consequently arrested on his 41st birthday by a team of 15 federal marshals. In court, Judge Takasugi ordered him to turn over the tape, but he said it was lost. The judge then ordered him to reveal who gave it to him. Flynt believed the government had no right to ask a journalist to reveal a confidential source and refused to give Judge Takasugi a direct answer. The judge lost his temper and threatened to fine Flynt $10,000 a day until he agreed to reveal his source. He ordered Flynt to appear before him the next day.

Flynt returned to court the following day, dressed in a diaper fashioned from an American flag. He figured if he was going to be treated like a naughty child, he was going to act like one. Surprisingly, the judge did not comment on the flag diaper, but a federal prosecutor had him arrested outside the courtroom. Flynt was charged with desecration of the flag.

His case landed in Judge Manual Real’s courtroom where Flynt, in excruciating pain, openly battled with the judge. At one point he spit at Judge Real, who ordered the bailiff to gag Flynt. Someone found a roll of tape and sealed Flynt’s mouth. Flynt promised to behave, but when the tape was removed, he shouted obscenities at the judge.

“I’m sentencing you to six months in a federal psychiatric prison!” the judge yelled, according to Flynt’s account. “Now get out of my courtroom!”

“Motherf***er — is that the best you can do?” Flynt responded.

“No! I’m making that 12 months!”

Flynt yelled back. “Listen, motherf***er, is that the best you can do?”

“Fifteen months!” the judge declared and stormed into his chambers.

Flynt served his sentence in two different prison facilities: Springfield, Missouri, and Butner, North Carolina. Hardly a model prisoner, the federal correctional system was glad to be rid of him when his time was up.

While Flynt was serving his prison term after his run-in with Judge Real, Hustler ran a satirical piece in its November 1983 issue that parodied a widely publicized ad campaign. Campari, the liqueur maker, ran a series of ads in major magazines that asked various celebrities to describe their “first time” with Campari. The titillating sexual double entendre was obvious and ripe for satire. Hustler put together a humorous version of the Campari “first time” ad, featuring the Reverend Jerry Falwell, leader of the Moral Majority. Flynt considered Falwell “one of America’s biggest hypocrites,” and the Hustler ad had the holy man describing his “first time” — in an outhouse with his mother “drunk off our God-fearing asses on Campari, ginger ale, and soda” and “Mom looked better than a Baptist whore with a $100 donation.” In small print at the bottom of the page was the message: “Ad parody — Not to be taken seriously.”

But the Reverend Falwell did take it seriously. He was so offended he filed a $45 million lawsuit against Flynt and his magazine. Ironically, the preacher hired Norman Roy Grutman, a New York attorney who regularly represented Bob Guccione and Penthouse. Grutman filed a complaint in Falwell’s backyard, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Virginia. In the complaint, Falwell claimed that the parody ad had used his name and likeness without his permission, that its content had libeled him, and that it had by intent inflicted emotional distress upon him. Judge James Turk was slated to hear the case in Roanoke.

Grutman deposed Flynt while he was still serving his sentence, and by Flynt’s own admission, he was “sick, drugged, angry, and overcome with pain.” His turmoil was reflected in his hostile, non-responsive answers. Knowing that this could be damaging to their case, Flynt’s lawyer, Alan Isaacson, filed a motion to throw out the deposition on the grounds that Flynt was in a manic-depressive rage that day as well as under the influence of strong medication.

Isaacson filed a second motion at the same time, claiming that Falwell’s attorney had paid one of Flynt’s former bodyguards $10,000 to swear that he had witnessed the Hustler publisher declaring that he intended to “get Falwell.” Judge Turk rejected both motions.

At the trial, Jerry Falwell took the stand and portrayed himself as a deeply religious “teetotaler” with a kind and saintly mother. Questioned by Grutman, Falwell conveyed the suffering he had endured as a result of the Campari parody. Later in the trial, conservative United States Senator Jesse Helms testified as a character witness, calling Falwell a “moral exemplar.”

When Flynt took the stand, his pain was under control and he was anything but the wild man he had been at his deposition, answering questions rationally and calmly. Isaacson asked him if it was his intention to damage Falwell with the Campari parody ad.

“If I wanted to hurt Reverend Falwell,” Flynt testified, “we would do a serious article on the inside [of the magazine] and make it an investigative expose and talk about his jet or whether he has a Swiss bank account. If you really want to hurt someone, you print something that is believable.”

In giving his instructions to the jury, the judge threw out the charge of illegal use of Falwell’s name and image. The jury deliberated for only one day and came back with a split decision. While they found that the Campari parody had inflicted emotional damage on the plaintiff, it also found that the ad had not libeled Falwell. The jury awarded him $100,000 in compensatory damages and $100,000 in punitive damages.

Flynt breathed a sign of relief. The fines were a “slap on the wrist” compared to what they could have been, and the amount was a drop in the bucket for the multi-millionaire publisher. But Flynt was more interested in the principle at stake, so he immediately appealed the decision, once again risking financial ruin in defense of his First Amendment rights.

A three-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit, considered Flynt’s appeal, but on August 5, 1986, refused to overturn the lower-court’s decision in the Falwell case. Flynt was outraged. As he writes in his autobiography, “For the first time in a major case, the court upheld the concept that liability could be predicated on mere intent to inflict emotional distress, even though the published material was neither libelous nor an invasion of privacy.” If this decision stood, the press would have to tread lightly when presenting material about public figures, and would have to withhold information to avoid defamation suits. Flynt was not about to let this happen, so he pressed on and exercised his right to request an en blanc hearing, in which all members of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals would hear his case, but the court decided by a one-vote margin not to rehear the case.

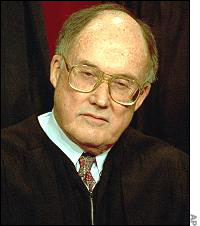

There was only one place left for Flynt to go: the Supreme Court, where his foul-mouthed antics the previous year had gotten him arrested for contempt of court. His attorneys filed a writ of certiorari to review the Court of Appeals’ decision, and on March 20, 1987, it was granted.

William Rehnquist was now chief justice, and he had a record of voting against the press in First Amendment cases. Recognizing the importance of Flynt’s case, the mainstream press — reluctantly at first — threw their support behind him. Friend-of-the-court briefs were submitted, first by the Richmond Times-Dispatch and the Richmond News Leader, then by the Times Mirror Company, the New York Times Company, the American Newspaper Association, the Magazine Publishers Association, the Virginia Press Association, the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, the Authors League of America, the ACLU, HBO, and political satirist Mark Russell.

The courtroom was overflowing with spectators on the day that the Supreme Court heard Flynt’s case. Both Falwell and Flynt were in attendance, but this time Flynt behaved and let his attorney, Alan Isaacson, do the talking. As is customary, each side was given 30 minutes to present its case, with the justices questioning the attorneys as they went along.

“There is public interest in having Hustler express its view that what Jerry Falwell says… is B.S.,” Isaacson argued. “And Hustler has every right to say that somebody who’s out there campaigning against it, saying… we’re poison on the minds of America… is full of B.S.”

The Court’s decision was not published until a year later on February 24, 1988. It was unanimous — 8-0 — in favor of Flynt.

Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote in his opinion: “The fact that society may find speech offensive is not a sufficient reason for suppressing it. Indeed, if it is the speaker’s opinion that gives offense, that consequence is reason for according it constitutional protection. For it is a central tenet of the First Amendment that the government must remain neutral in the marketplace of ideas.”

The decision made it clear that public figures who were presented in parodies and satires could not sue simply because their feelings were hurt.

While awaiting the Supreme Court decision, Flynt’s wife Althea, diagnosed with AIDS and addicted to drugs, drowned in the bathtub at their California home at the age of 33. Flynt had her body flown to Kentucky and buried at the Flynt family graveyard in Lakeville. Theirs had been a unique relationship. According to author John Heidenry, he occasionally beat her. In an interview in Hustler, Althea once said, “I don’t see anything wrong with a man striking a woman. In fact, many women are turned on by it.” While she was married to Flynt, Leasure also had several relationships with women.

Heidenry, in his book What Wild Ecstasy, claims that Althea’s death was actually a murder ordered by Mafia loan sharks from south Florida. According to Heidenry, Flynt was “deeply in hock” to the mob, and they felt that Althea “knew too much” and had to be eliminated.

Flynt, the father of five children, married his fifth wife, Liz Berrios, in 1998. Berrios had been his nurse.

In recent years, one of Flynt’s daughters, Tonya Flynt-Vega, accused him of sexually molesting her, and in 1998 she published a book about her childhood experiences and her later spiritual awakening. According to Slate, a former brother-in-law gave Penthouse an interview in which he accused Flynt of molesting another daughter. Charges were never filed against him.

While Flynt’s detractors see him as the most vulgar pornographer the country has ever seen, he prefers to wear the mantle of First Amendment protector and deflator of two-faced politicians and self-appointed saviors. In 1998, when the Republican-led Congress was clamoring for the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, wagging prudish fingers at the president’s affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, Flynt offered $1 million to anyone who could provide him with evidence of sexual shenanigans among Republican lawmakers. He made the same offer in a 2007 Washington Post ad, asking for proof of sexual affairs conducted by government officials or members of Congress.

Enthroned on his gold-plated wheelchair, Flynt wears his veneer of sleaze as proudly as his garish shirts and gaudy jewelry. But as he has said many times in and out of court, sleaze is not a crime, and Americans have a constitutional right to publish it and read it if they chose to. To many, he appears to be a man without morals, but Flynt has shown that even he has scruples. He had obtained nude photographs of Private First Class Jessica Lynch, the soldier who was dramatically rescued from her Iraqi captors in 2003. He had intended to publish them but then had second thoughts. Flynt and other critics of the Bush Administration felt that she was unfairly used by government officials to garner support for the war. Though he said he paid $750,000 for the photos, Flynt decided not to release them, saying that Lynch was a “good kid” who got caught up in the government’s propaganda machine.

Director Milos Forman made a film based on Larry Flynt’s life, The People vs. Larry Flynt, starring Woody Harrelson as Flynt and rock star Courtney Love as Althea Leasure. It was released in 1996.

Biography: Fighting Dirty. A&E. 2001.

Dunder, Jonathan. Larry Flynt. The Free Information Society. www.freeinfosociety.com/site.php?postnum=72.

Flynt, Larry. Sex, Lies, and Politics: The Naked Truth. New York: Kensington Books, 2004.

Flynt, Larry with Kenneth Ross. An Unseemly Man. Los Angeles: Dove Books, 1996.

Heidenry, John. What Wild Ecstasy: The Rise and Fall of the Sexual Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Hohlt, Jared. Reality vs. Larry Flynt. Slate. 25 Jan. 1997. www.slate.com.

Smolla, Rodney A. Jerry Falwell v. Larry Flynt: The First Amendment on Trial. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988.