Typhoid Mary was a cook who passed typhoid to people for whom she cooked the Crime Library — ‘Boss Man’ McGee — Crime Library

His story was the darkest side of whispered urban legends that often turn out to be nothing but myths. But in 1996, these events became a harsh and disturbing reality. He was called “Boss Man,” and he roamed through the battle-scarred streets of East St. Louis, where boarded-up storefronts and burned-out cars are a common sight. Frequently at the wheel of expensive, flashy cars, the “Boss Man,” whose real name was Darnell McGee, was known as a ladies’ man, and rumors of his many conquests, including some very young girls, swept through the riverside slum in 1996. Though his source of income was unknown, McGee always seemed to have a lot of cash and would often take his girlfriends on shopping trips and lavish them with gifts. To a young girl from East St. Louis, the attention may have been irresistible. But that happiness was short-lived and quickly turned to horror when it was revealed that Darnell “Boss Man” McGee was not only infected with the AIDS virus, but was spreading it to all his sex partners. According to a report in the Times, at least 62 women had been exposed to the deadly virus as a result of McGee’s conduct (April 19, 1997).

“Investigators say McGee preyed on girls with low-self esteem, making them feel more important with flattery and gifts, and would pick them up in front of schools, liquor stores and skating rinks,” reported the Associated Press (Farrow). When authorities first learned about the story, an intensive search was conducted to locate and identify the victims. But they had to search without his help. On January 15, 1997, the “Boss Man” was shot and killed while driving through the mean streets of St. Louis with his latest girlfriend by his side. At the time, some cops speculated it may have been revenge from one of his many victims. But later, it was determined to be an ordinary street robbery. Had he lived, Darnell McGee may well have been prosecuted for his incredibly vicious conduct. Intentionally spreading the HIV virus is a felony in both Illinois and Missouri. “He was a lunatic,” said one girl to the press. “He knew he was going to die. He was going to take as many people with him as he could” (Nossiter).

The idea of someone intentionally passing on a fatal disease is a plausible nightmare. “I’d characterize it as despicable,” said one law enforcement official to the press. “It’s horrifying” (Barron). But human carriers who spread infections are, in fact, more common than is believed. In 1999, a New York man pleaded guilty to reckless endangerment in the first degree after exposing his sex partners to the HIV virus. But “authorities believe (he) had sex with more than a dozen young women in upstate New York without telling them he had the virus” (February 27, 1999, Times).

However, one of the first and most notorious healthy carriers of a contagious disease was not either of these individuals. That distinction belongs to a rather obstinate and disagreeable female who passed on her disease to hundreds, perhaps thousands of innocent people during a period when America was much more susceptible to epidemics than it is today. Her name was Mary Mallon. But she was better known by the title bestowed on her by New York’s feral tabloids: Typhoid Mary.

In the beginning of the 20th century, the threat of a national epidemic was very real. Though great strides were made during the previous fifty years in the field of epidemiology, people still lived in fear of contagious diseases. That fear was well-justified. During the Civil War period, more deaths were caused by disease than battle wounds. Typhoid and dysentery together claimed over 280,000 lives during that conflict. It was also believed that over 35,000 deaths were attributed nationwide to typhoid in 1900 alone. Many diseases spread rapidly due to sub-standard sanitary conditions and a lack of understanding as to how they were transmitted. Typhoid was especially feared because it seemed to be everywhere and outbreaks of the sickness seemed common.

In 1903, an epidemic of typhoid struck the city of Ithaca, New York. In its initial stages, the sickness was misdiagnosed as a type of flu. Within a few weeks, hundreds were infected. Only then was the correct diagnosis made. Within four months, the Health Department counted 1,350 of the city’s 13,000 residents sick with typhoid, and 85 eventually died. To place these numbers in perspective, if a similar outbreak occurred in New York City today, over 800,000 people would be afflicted. “To date 19 Cornell students have died from typhoid,” reported the New York Times, “of whom 18 were male students. This makes almost 1 per cent of the male students of Cornell who have died of the fever within three weeks” (March 3, 1903). In a state of panic and unable to understand how the epidemic progressed, the City Council of Ithaca hired Dr. George A. Soper, a sanitary expert, who had studied typhoid and how it was transmitted in humans.

Soper immediately tested the city’s water supply and discovered a large portion of the system was infected with typhoid bacillus. Further investigation revealed that an antiquated sewage system allowed cesspools to drain directly into clean creeks and streams. In other words, human waste was leaking into the water supply. Soper took steps to correct the problem by upgrading the sewage system and sealing up the infected areas. These measures stopped the disease in its tracks, and undoubtedly many deaths were averted. But it was still not clear how the epidemic got started in the first place.

Did it just naturally develop in the contaminated wells? Did someone intentionally bring the typhoid germ to Ithaca? Even Soper himself could not answer those questions.

The first sign of trouble began in the late summer of 1906, when a small epidemic broke out in a home in the town of Oyster Bay, New York. Six occupants in a house of eleven were taken ill with typhoid fever for no apparent reason. The location was in an upscale, wealthy section of Long Island where properties were typically sanitary and well-kept. Anthony Bourdain, in his book, Typhoid Mary, describes it as “a popular vacation spot for wealthy urban New Yorkers, it was best known for hosting President Theodore Roosevelt during the summer” (13). A New York City businessman named Charles Henry Warren had rented the residence for the season, and in August that same year; six family members became gravely ill.

Two of those afflicted were diagnosed with typhoid at Nassau County Hospital. A medical investigation was begun, which included a study of the food supply that came into the home during the previous month. Special attention was paid to milk and other dairy products, which were primary suspects in the spread of diseases. The drainage and water supply were also tested and found to be in fine working order. Water sources were thought to be especially vulnerable to typhoid due to leakage from cesspools and septic systems that were a common sight on most rural properties at that time. However, none of these proved to be the source of the infection.

In the winter of 1906, the family called in the same Dr. Soper, who had investigated the notorious Ithaca epidemic in 1903. He soon focused on the family’s food consumption, which included a fondness for clams. Local natives, who gathered them from waters that were considered unsafe, brought the mollusks to the Warren household. Soper discovered that a local sewage pipe drained into the bay from which the clams were harvested. For a moment, he thought he had found the source of the mysterious illness. “But if clams had been responsible for the outbreak,” Soper later wrote, “it did not seem clear why the fever should have been confined to the house, because clams formed a common article of diet among the native inhabitants of Oyster Bay” (Soper 3). Further investigation convinced Soper that the infection had to be introduced into the Warren household on or before August 20.

Because there were no other cases of typhoid in or near Oyster Bay, it soon became obvious that the disease was introduced into the home by an outside carrier. When Soper questioned the family, he discovered an interesting fact. “It was found that the family had changed cooks on August 4 about three weeks before the epidemic broke out.” he noted, “and little was known about the new cook’s history … she remained in the family only a short time, leaving about three weeks after the outbreak of typhoid occurred” (Soper 3). The cook was an Irish woman, about forty years old, tall, and seemed to perform her duties in a conscientious manner. Everyone in the Warren family agreed on one point, however: The woman was in perfect health and was never sick while she was living in the house.

According to the Warrens, her name was Mary Mallon.

Although the concept of a healthy carrier was not well understood in 1909, some physicians were aware of this special type of condition. They knew it was possible that a person could spread the infection without any outward signs of the disease. “While this seemed a likely theory, no one had ever identified an actual chronic carrier,” according to an article in American Heritage (Gordon 120). People who were thought to be infected were often treated as pariahs and sometimes quarantined for long periods until physicians could figure out what do with them. Soper suspected right away that Mary Mallon was a carrier. He began to investigate all of her previous employers.

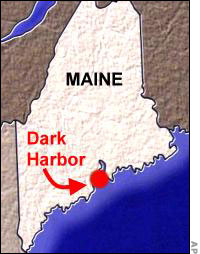

Using her employment agency as a guide, Soper discovered that a trail of typhoid followed Mary Mallon wherever she went. In the previous ten years, eight households in which she worked as a cook developed typhoid either during her employment or shortly afterwards. In the most serious case, at Dark Harbor, Maine, seven of nine people became infected shortly after Mary was hired as a cook. When the children became stricken with typhoid, she stayed on and nursed them back to health. Her employer, a New York City attorney named J. Coleman Drayton, gave her a financial bonus to demonstrate his thanks. A later investigation into the source of the outbreak was inconclusive. And because Mary was not sick herself, she was never suspected as being infected with the dangerous bacteria.

In all, “Soper identified twenty-two cases of typhoid in his search of Mary Mallon’s employment between 1900 and 1907…this number is actually quite small and indicates that many of the people for whom Mallon cooked during these years may have already been immune to typhoid by virtue of having recovered from the disease” (Leavitt 18). Soon, Soper began to track Mary herself in the hope he could find her and examine her for typhoid. “I supposed that she would be glad to know the truth and to be shown how to take such precautions as would protect those about her against infection,” Soper wrote later. “I thought I could count upon her cooperation in clearing up some of the mystery which surrounded her past.”

The elated doctor rushed over to Park Avenue, where he expected to find a gratified Mary Mallon who would thank him for stopping the spread of a deadly disease. What he found, however, was something entirely different.

Not much factual information is known about Mary Mallon prior to 1907. She was born in Ireland in 1869 and arrived in America sometime in the 1890s. Tall, sturdily built and apparently healthy, she was a quiet person who mostly kept to herself (Gibbons). Mary seemed to be educated, liked to read and also could write very well as her surviving letters indicate. It is unclear if she had any formal training as a cook, although it is obvious she enjoyed cooking and relied upon her skills for her livelihood. Mary sought employment through want ads and job agencies in New York City and Boston. Mostly, she worked as a cook in private residences for wealthy families.

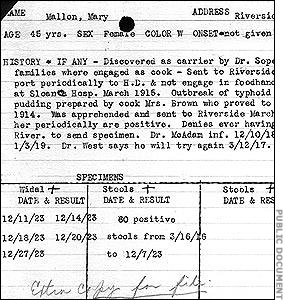

Mallon

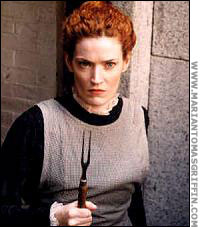

When Dr. Soper arrived at the Park Avenue home in the spring of 1907, he had high expectations and was convinced he was performing a valued public service. He confronted Mary Mallon in the kitchen and described the trail of typhoid that she left behind. After a few minutes, Mary became angry. “Mary did not see Soper as the answer to some long-troubling question about the series of odd and unpleasant coincidences that had long followed her,” writes Bourdain (26). When Soper told her that he needed to take blood and urine samples from her, she became enraged. Mary picked up a large carving fork and advanced upon the doctor. Soper ran from the house, with Mary not far behind. He jumped a nearby fence and escaped unharmed. But later that same day, an assistant staked out the rooming house where she was staying. He watched as Mary entered and exited and soon he was able to gain entry to her room.

According to his report, it was a pigsty; unsanitary beyond words and covered with dog feces and urine stains. The assistant told Soper that he would not be surprised if typhoid bacteria was propagating in the filth. Soper made an arrangement to meet with Mary again, and this time he brought along a friend, Dr. Raymond Hoobler. Together, they tried to explain to Mary their suspicions that she was a carrier of typhoid, and that by her unsanitary habits, she was spreading the disease wherever she went. “Dr. Hoobler and I described the situation with as much tact and judgment as we possessed,” Soper later wrote. “We explained our suspicions. We pointed out the need of examinations which might reveal the source of the infectious matter which Mary was producing” (Soper 6). But Mary was strong-willed and adamant as well. She wouldn’t listen to reason. She refused to believe Dr. Soper and would not submit to an examination.

True to her belief that she was not a carrier of typhoid, Mary went back to work. She continued to cook for the same Park Avenue family much to the dismay of Dr. Soper and the health authorities. Why her employer didn’t terminate her at this time is unknown. But clearly something had to be done. If Mary was allowed to remain working as a cook, there was no telling the amount of damage she could do. And if she should disappear and get a job in a public restaurant somewhere, the results could be disastrous.

Because of the growing fear of typhoid in New York City and with the Ithaca epidemic of 1903 still fresh on the public mind, Dr. Soper decided to visit the city’s chief medical officer, Dr. Herman Biggs. He explained that Mary Mallon was almost certainly a healthy carrier and the danger of letting her remain at large in the general population was an enormous health risk. It was only a matter of time, Dr. Soper said, before she would initiate a full-scale epidemic that could kill hundreds or even thousands of people. Dr. Soper requested that Mary be taken into custody and the required samples be forcibly taken from her.

This was a drastic step, and one that had never happened before in American history. No healthy person had ever been taken into custody under such conditions and held against her will without a trial. It was a violation of Mary’s constitutional rights to due process of law as an American citizen. But the health of the public was of primary concern, and soon, the board decided to act. “Biggs and his Health Department colleagues found Soper’s epidemiological evidence sufficiently compelling to follow through on his suggestions” (Leavitt 20).

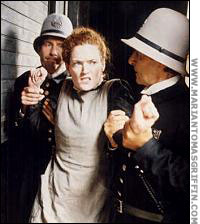

On March 19, 1907, an ambulance, Dr. Soper, Dr. S. Josephine Baker and three cops showed up at the Park Avenue home where Mary Mallon had been hired as a cook. The police surrounded the building as best they could while Dr. Soper knocked on the front door. Mary answered the door, but as soon as she saw an officer out front, she slammed the door shut and ran. She seemed to have disappeared, and a search was quickly begun. When officers checked through some trash cans behind the home, Mary was found hiding behind the garbage. Officers grabbed her and tried to restrain the hysterical woman. “She came out fighting and swearing, both of which she could do with appalling efficiency and vigor,” said Dr. Baker (Leavitt 46). She bit two of the officers before they managed to handcuff her and drag her to the waiting ambulance out front.

She was taken to a detention center at the Willard Parker Hospital located at the foot of 16th Street on the East River. “I literally sat on her all the way to the hospital,” Dr. Baker said later. “It was like being in a cage with an angry lion” (Leavitt 46). When she later tested positive for typhoid, Mary was removed from the hospital and taken to North Brother Island, located in the East River between Riker’s Island and the rocky shores of the south Bronx.

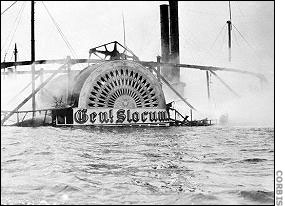

North Brother Island, all of twenty acres, was used at that time primarily as a treatment and quarantine center for tuberculosis patients. But it was famous for another reason. In June 1904, the ferry General Slocum caught fire while steaming up the East River on a church outing carrying 1,200 passengers. The fire began in the bow of the vessel and quickly spread to the rest of the boat trapping hundreds of people below deck. Instead of heading for shore immediately, Captain William Van Schaick proceeded at high speed to North Brother Island. The brisk winds fed the flames and as a result, over 1,000 men, women and children lost their lives in the fire. “For hours after the disaster the waters around North Brother Island were thick with dead bodies, and these were pulled aboard all kinds of craft as quickly as they could be and laid out in awful rows on the pier,” reported the Times (June 16, 1904).

Riverside Hospital, located in the center of the island, was the place where health officials placed patients with infectious diseases when no one knew what else to do with them. Mary, however, was not placed with the TB patients. She was allowed to live in a one-story bungalow on the grounds of the hospital where she could cook her own meals and live in relative seclusion.

For the next three years, Mary Mallon, made famous by the tabloids as “Typhoid Mary,” remained on the island, living like an outcast and never having been charged with any crime. “When I first came here,” she wrote in a letter, “I was so nervous and almost prostrated with grief and trouble. My eyes began to twitch and the left eyelid became paralyzed and would not move” (NOVA). Some civil libertarians thought that her imprisonment without due process was an affront to the laws of the land. Others, especially those in the medical profession, applauded the move. Leavitt writes in “Typhoid Mary,” “many scientists believed that Mary Mallon’s apprehension in 1907 was a momentous event, one in which the new science of bacteriology played a heroic role” (30). In 1909, Mallon’s attorney filed a suit in city court demanding that she be released. He said that her incarceration was a violation of her constitutional rights. But the New York City Health Department contended Mary was a carrier of typhoid and a danger to public health. One doctor called her “the most dangerous person in New York!” (Wolf and Mader 171). But Mary herself proclaimed her innocence every chance she got. “I have worked in scores of places where there has been no typhoid,” she told a reporter, “and even now, I mingle with the doctors and cook for them. Besides, I play with the children in the various wards and they are none the worse for it” (July 20, 1909, Life).

The court rejected her appeal and decided Mary must remain on the island. The New York Times reported, “the court … did not care to assume the responsibility of releasing her” (July 17, 1909). However, the court left the door open for the future and said that if she could be cured, there would be no reason to hold her. “While the court deeply sympathizes with this unfortunate woman,” wrote Justice Mitchell Erlanger, “it must protect the community against a recurrence of spreading the disease. Every opportunity should … be afforded her to establish that she has been fully cured and she may … renew the application” (Times 3).

Mary resigned herself to a barren existence on North Brother Island. Every night she would go to sleep with the tantalizing vision of the Manhattan skyline in her thoughts. From her cottage, she could easily see the tall buildings and the night-lights of America’s largest city just a stone’s throw away from her door. She saw herself as a prisoner who had committed no crime, a martyr to a tenuous and doubtful science. “I have been a peep show for everybody,” she wrote in a letter in 1910. “Even the interns had to come to see me and ask about the facts already known to the whole wide world. They would say ‘There she is, the kidnapped woman!” (NOVA).

Ever since she was incarcerated against her will, “Typhoid Mary” became the focus of a growing controversy. Many people were of the opinion that keeping her a prisoner, although she had committed no crime, was a violation of American civil rights, and the New York press echoed this sentiment. One letter writer to the Times wrote, “If one unfortunate woman must be labeled Typhoid Mary…start a colony on some unpleasant island, call it ‘Uncle Sam’s suspects’ there collect Measles Sammy, Tonsillitis Joseph, Scarlet Fever Sally, Mumps Matilda and Meningitis Matthew” (Leavitt 83).

By 1910, public sentiment favored Mary’s release and the courts were weakening in their resolve to keep her prisoner. “She has been shut up long enough to learn the precautions she ought to take,” said Health Commissioner Lederle in February that year. “As long as she observes them, I have little fear that she will be a danger to her neighbors” (February 21, 1910, Times). Over time, even Dr. Soper himself recognized the legal issues in the case. “She was held without being given a hearing,” he said. “She was apparently under life sentence; it was contrary to the Constitution of the United States to hold her under the circumstances” (Leavitt 82). But again, Mary refused to acknowledge that she was a carrier. “I never had typhoid in my life,” she later said, “and have always been healthy. Why should I be banished like a leper and compelled to live in solitary confinement with only a dog for a companion?”

Responding to public pressure and fearful of being the target of a lawsuit, the Health Department cut a deal with Mary. She could leave the island and return to a normal life if she would not hire out as a cook and report to the Health Department for periodic examinations. Mary agreed and on February 20, 1910, she was released. The Health Department Commissioner told reporters that “the chief points she must observe are personal cleanliness and the keeping away from the preparation of other person’s food” (February 21, 1910, Times).

Mary was taken by ferry to the Bronx mainland, where she walked off the boat a free woman for the first time in nearly three years. Though she was no longer a prisoner, Mary had very few options open to her. She had no money, few friends and could no longer work in her chosen profession. Her outlook was bleak. In December of 1911, Mary filed a lawsuit against New York City and its Health Department. She claimed she had been unlawfully imprisoned without a trial and against her will and demanded $50,000 in damages. Her attorney, George Francis O’Neill, told reporters, “If the Board of Health is going to send every cook to jail who happens to come under their designation of ‘germ carrier,’ it won’t be long before we have no cooks left!” (December 3, 1911, Times).

The lawsuit was eventually dropped, and within a few months, Mary had disappeared, melding into the lower echelons of Manhattan existence. She reported to the Health Department only on several occasions and then never came in for examination again. By 1915, “Typhoid Mary” was mostly forgotten except for a few instances when newspapers reported on the subject of typhoid fever. Author Bourdain writes, “she’d been publicly reviled, nicknamed with an unforgettable moniker, locked up, poked, prodded, examined, interviewed, depicted in photos and illustrations, gossiped about, teased and now as back at the bottom” (Bourdain). Exactly where she went during those few years is unknown though she was suspected of living in New Jersey and Connecticut. Attempts were made to locate her, but those efforts failed. Mary could not find work to support herself, and ultimately, she was forced to return to the only profession she knew: cooking.

“I have been unable to learn her complete history during this period,” later wrote Dr. Soper, “but from the fragments which have been collected, it is apparent that she continued to enact her hateful role of typhoid producer” (Soper 9). In February 1915, an epidemic of typhoid suddenly erupted at the Sloane Hospital for Women on W. 59th Street. Twenty-five nurses and attendants in the hospital became violently ill and were unable to work. Health inspectors rushed over to the facility, which was panic-stricken and unable to function until the problem was resolved. Sloane was known primarily as a maternity hospital, so the threat of typhoid fever was that much more frightening. Investigators, led by Dr. M. L. Logan from New York’s beleaguered Health Department, focused initially on the institution’s water supply. But that source was quickly eliminated when the water was found to be safe.

Dr. Logan then turned his attention to the hospital kitchen, where all meals, including those for employees, were prepared. The Times reported that a cook “prepared a certain suspected food which is known to have been partaken of by the doctors and nurses but not so certainly by the rest of the hospital force” (March 28, 1915). Because none of the patients became ill, this seemed a likely source for the disease. Two people soon died, and management prepared for a shutdown. Some people joked about the possibility of “Typhoid Mary” working in the hospital kitchen. They didn’t know how accurate they were.

After examining all the kitchen help, authorities focused their suspicions to a female cook who tested positive for typhoid. However, the next day, she failed to appear for work. N.Y.P.D. Officer John Bevins, who had seen the woman years before, reported to the Health Department that he recognized her from years ago as the real “Typhoid Mary.” Investigators checked hospital records and found that the woman gave her address as a private house in Corona, Queens. The police hastily put together an arrest team and hurried over to the location.

When they arrived, they knocked on the door for several minutes but received no answer. A ladder was taken from a nearby home and placed on a second floor window. When cops entered, they found the home empty. But after an extensive search, they discovered Mary hiding in a bathroom. “As they went from room to room the muffled door slamming was always just ahead of them,” reported one local newspaper. “At last, they pushed open the door of a bathroom and found a woman crouching there. She told them finally … she was Mary Mallon!” (Leavitt 150). This time, she surrendered without a struggle and was taken back to Manhattan in handcuffs while officials decided what to do next.

In the meantime, the extent of the typhoid outbreak was just beginning to be made public. “One death occurred in a nurse who had received only a partial immunization in 1912,” one health official told reporters. “Another sudden death … occurred in a chambermaid 65 years of age, in the second week of her illness (March 28, 1915, Times). It was plain for everyone to see: Mary Mallon had intentionally infected innocent people by her callous and reckless behavior.

But what should be done with her?

When it became know that Typhoid Mary had struck again, there was an immediate public uproar. Only two years before, there was a fierce outbreak of typhoid on Manhattan’s upper East Side. Hundreds were infected and the disease spread rapidly. “The lives of thousands of children are daily placed in jeopardy,” said one resident to the mayor. “The disease is growing and is the product of absolute indifference on the part of officials to enforce the sanitary laws” (September 29, 1913, New York Press).

Fear of infectious diseases was very strong in the public mind and because epidemics were not well understood, officials felt a great deal of pressure to do something about “Typhoid Mary.” She had ignored warnings, refused to cooperate with health authorities and intentionally spread typhoid among the general population. “The publicity given the career of ‘Typhoid Mary’ has marked her as the most celebrated germ-carrier in the world,” said the Times (March 28, 1915).

Some people wanted her charged with murder for the two deaths at Sloane Hospital while others wanted Mallon locked up for good. “Here she was,” said Dr. Soper a few days later, “dispensing germs daily with the food served up to the patients, employees, doctors and nurses of the hospital-a total of 281 persons. Twenty-five of this number were attacked by typhoid before the epidemic could be checked (April 4, 1915). Newspaper editorials lobbied against her and gone was the sympathy Mary received when she was first incarcerated in 1909. “A chance was given to her five years ago to live in freedom and she had deliberately elected to throw it away,” said the Herald Tribune (Hasian 134).

But the Health Department already knew that an appeal to the criminal courts was not necessary. The issue had already been decided under Section 1170 of the Charter of Greater New York. The statute read, “it (the Health Board) shall require the isolation of all persons and things exposed to such diseases … The danger to the public health is a sufficient ground for the exercise of police power in the restraint of liberty of such persons” (Bourdain 107-108). By order of the health department, Mary was taken back to North Brother Island and placed in isolation.

However, she was still defiant and saw herself as a victim of bureaucrats who would stop at nothing to imprison her. “As there is a God in heaven,” she once said to a New York reporter, “I will get justice, somehow, sometime” (Leavitt 142).

As time passed, Mary became accustomed to her fate. Though she was supposed to be kept in isolation, she eventually came into contact daily with nurses and doctors from Riverside Hospital. After a few years, she was allowed to work as a lab assistant at the hospital, though she was carefully monitored. But she knew virtually nothing about lab work or the health profession. Mostly she prepared paperwork for the physicians and performed office maintenance. But her legal status was still unclear. She was perceived as a criminal but never convicted of a crime. Though she tried to bring her case into a court of law, it never happened.

Life on the island was a mixture of serenity and isolation. Though it was located just hundreds of yards from the coast of the Bronx, it had a certain country feel to it. “This is heaven,” one visitor remarked when she first set foot on the island. “It’s delightful, other-worldly, unlike New York City” (Bourdain). For Mary though, the experience was different. “A few more years of this kind of life and I shall go insane,” she once told reporters from Life magazine. “I have committed no crime, but am innocent. I am doomed to be a prisoner for life!” (July 20, 1909).

For the next twenty-three years, she lived in isolation on North Brother Island in the same cottage where she was imprisoned years before. To her detriment, Mary never understood typhoid fever. She never believed that she had the disease because she was never ill. She could not accept the fact that some people can contract a mild case of typhoid, which could resemble a bout with the flu, and continue to spread the disease even after a complete recovery.

It is difficult to assess the damage caused by Mary’s refusal to acknowledge her sickness. At least three deaths were attributed to her and possibly hundreds of cases of typhoid as well. Some researchers blame the start of the famous Ithaca epidemic of 1903 on her though there is no hard evidence this is true (Gibbons). Nor was she the only healthy carrier during that period. Health officials know that between two and three percent of all typhoid cases can develop into carriers. Because New York City experienced at least 4,000 cases of typhoid in 1910, that would indicate approximately 90 new carriers in that year alone.

In December 1932, Mallon suffered a severe stroke, which left her partially paralyzed. When she was found lying on the floor of her cottage, doctors were repelled by what they saw. “The stench that came out of that doorway,” one friend later remarked, “…grimy, filthy-looking on the outside. I called and there was no answer. I could barely get the door open because there was so much junk … I almost slid into the place because it was so filthy. The odor was overwhelming” (Bourdain).

But she continued to work in Riverside Hospital for the next six years. She had few visitors, and those that came were careful not to stay past dinnertime. Her personal hygiene never improved and her slovenly appearance shocked many. “I walked into that building (the hospital),” said one visitor, “…and a huge woman in there who kind of terrified me with her hair unkempt pulled back in a tight knot and a huge lab coat which enfolded her despite her size at least double to the floor filthy as hell with all kinds of stuff on it. And they told me this was Mary Mallon” (Bourdain).

In 1938, she died as result of the effects of the earlier stroke. Only nine people attended her funeral mass in St. Luke’s Church in the Bronx (November 13, 1938, Times). She was buried in nearby St. Raymond’s Cemetery. Her tombstone reads Mary Mallon Died Nov 11 1938 and, on the bottom of the stone, the words Jesus Mercy appear. But she will always be known as “Typhoid Mary.”

Barron, James. Officials Link Man to 11 Teen-Agers With H.I.V. October 28, 1997; New York Times.

Bourdain, Anthony. Typhoid Mary. New York City, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001.

Farrow, Connie. Report: Man Gave HIV to 18 Females; February 11, 1998, Associated Press.

Gibbons, L.N. Mary Mallon: Disease, Denial and Detention. Journal of Biological Education; Summer98, Vol. 32, Issue 2, 127-133.

Gordon, John Steele. The Passion of Typhoid Mary. American Heritage, May-June 1974, p. 118-121.

Hasian, Marouf A. Jr. Power, Medical Knowledge, and the Rhetorical Invention of “Typhoid Mary.” Journal of Medical Humanities, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2000, 123-139.

Leavitt, Judith Walzer. Typhoid Mary: Captive to the Public’s Health.Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

5,000 Children to Fight Typhoid, September 29, 1913: New York Press.

Nossiter, Adam. Man Knowingly Exposed 62 Women to AIDS Virus, April 19, 1997; New York Times.

NOVA: The Most Dangerous Woman in America. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/typhoid/mary.html. October 26, 2005.

Ithaca’s Typhoid Epidemic, March 3, 1903; 1,000 Lives May Be Lost in Burning of the Excursion Boat Gen Slocum, July 16, 1904; “Typhoid Mary” Must Stay, July 17, 1909; “Typhoid Mary” Freed, February 21, 1910; ‘Typhoid Mary’ Asks $50,000 From City, December 3, 1911; Hospital Epidemic From Typhoid Mary, March 28, 1915; “Typhoid Mary” Has Reappeared, April 4, 1915; Man Pleads Guilty in Rape Cases and Exposing Woman to H.I.V., February 27, 1999; Typhoid Mary Buried, November 13, 1938; New York Times.

Typhoid Mary Wants Freedom, July 20, 1909; Life.

Williams, Geoff. Recipe for Disaster: How Mary Mallon Became Typhoid Mary. Biography; December 97, Vol 1 Issue 12, 69-72.

Wolf, Marvin and Mader, Katherine. Typhoid Mary; Rotten Apples: Chronicles of New York Crime and Mystery. New York City, NY: Ballantine Books.