The Murder of Daniel Williams — A Double Life — Crime Library

LOS ANGELES, Monday, Dec. 22, 1997 —

The body lay sprawled across the blood-stained sidewalk.

At first glance it appeared to be a woman. There was the long hair, the turquoise blue dress, and the maroon sweater. But the body lying on its back in front of 1239 South Compton Ave., in South Central Los Angeles, was not a woman, despite the matching red lace bra and panties.

She was a he.

The evidence was unmistakable. From beneath the wig, which sat askew atop the person’s head, peeked the receding hairline and close-cropped scalp of a middle-aged man. Additionally, the raised dress, hiked up nearly to the hips, and the low-slung panties, pulled down almost to the knees, gave any curious onlooker an unobstructed view of a penis.

A passerby called 911 at about 6:00 a.m.

Less than an hour later, four detectives from the Los Angeles Police Department’s Newton Division had gathered at the scene.

“It was pretty obvious he was a man dressed as a woman,” Detective Kelly Baitx says.

The body had fallen next to a blue trash dumpster. Two .25-caliber shell casings lay on the ground nearby. Behind the dumpster, a wooden fence separated the street from one of the many businesses in the neighborhood.

The area around 12th and Compton is an industrial district, bustling during the day but deserted at night. Except for the street people — hustlers, dope peddlers, pimps, and prostitutes.

“It’s a hell of a way to die, and a hell of a place to die,” one of the homicide detectives later said.

A key characteristic of any good homicide investigator is the ability to simultaneously do two seemingly contradictory things: keep an open mind, one that allows for consideration of any potential avenue of investigation; and use his or her experience and knowledge of the streets to quickly narrow down the almost infinite number of possible scenarios that could have led to a body lying dead on a sidewalk on a cold and windy morning.

The average homicide cop in South Central L.A. carries eight to 15 open, active cases.

On average, each detective picks up a new murder case every four to six weeks. That kind of murder rate doesn’t leave a detective with a lot of time to engage in wild speculation or flights of fancy.

The case of a man dressed in drag and found shot dead with a small caliber handgun on a street known for drug dealing and prostitution — both male and female — probably wasn’t going to involve high-dollar contract killers, Middle Eastern terrorists, or international drug cartels. Those potential avenues of investigation could probably be closed right away.

Another clue that the case might be more pedestrian, lay unseen during the detectives’ initial survey of the crime scene, but showed itself when the coroner’s investigators rolled the body over to examine its underside.

Beneath the man’s body, investigators found a used condom.

When the coroner’s men rolled the body over, the detectives also discovered the source of all the blood that had spilled onto the sidewalk: a bullet hole in the back of the victim’s skull.

A black purse lay near the body but it contained no identification. The lack of ID did not come as a surprise to the detectives. Prostitutes rarely carry valuables or identification. In a business as rough as streetwalking, where robbery is common and where cops frequently run prostitutes’ names for warrants, traveling light is a survival skill.

With no information to go on other than what they gleaned from the crime scene, the detectives formed an initial theory about what may have happened to the victim. They had a likely transvestite prostitute shot in the back of the head. The presence of the victim’s purse seemed to rule out robbery. The pulled down panties and used condom indicated the victim was engaged in or had just finished having sex when the killing took place. The lack of semen in the condom indicated that whoever had been wearing it may have been interrupted

The guy who pulled off the condom must have seen something, the detectives reasoned. Likely, he was either the perpetrator or a witness.

A murder investigation is a complicated puzzle. It has an unknown number of pieces and no picture on the box top to use as a guide. Each uncovered fact adds a piece to the puzzle and each piece reveals a little bit more of the as-yet-unseen picture.

“The lifestyle (is) something you take into consideration,” Detective Baitx says. “You’re definitely going to look at what he was doing for a living (and) the area he was living in to come up with how the case (is) going to be worked.”

From what the detectives at the crime scene could see so far, the victim’s occupation was pretty obvious.

“He was making a living having sex for money on the street,” Baitx says.

Most people who get murdered get murdered for a reason. They make somebody mad, they get into a fight, they get robbed, they go to the wrong place at the wrong time. To solve a murder, a homicide investigator has to get to know the victim. In most cases, it’s the only way to figure out why the murder happened; and an investigator who figures out the why, can usually figure out the who.

There are many things an investigator needs to know about a victim but the answers to four important questions stand out:

Who was the victim? What kind of person was he or she? What was the victim involved in? Did he or she have enemies willing to kill?

The obvious difficulty in getting to know a murder victim is that the victim is dead. Still, detectives have to find answers somewhere. Friends, family, co-workers, acquaintances, even enemies — all can give investigators valuable information about a murder victim. Detectives then plug that information into a timeline.

In the majority of murder investigations, the most important stretch of time, at least from a homicide investigator’s perspective, is the last 24 hours of the victim’s life. In most cases, something happened within those last 24 hours that directly led to the murder.

Homicide is a tale told in reverse. Detectives already know the ending. They just have to figure out the beginning. To do that, they need to find out what the victim was doing, when he or she was doing it, and with whom.

The initial step in meeting someone — whether dead or alive — is usually to get the person’s name. In the case of the dead man on South Compton Avenue, wearing women’s clothing with a wig cocked sideways on his head, the detectives had no idea who he was.

“Until you can find out who the victim is,” Baitx says, “where they live, and where they hung out, you’re at a standstill.”

The first thing the detectives needed from the victim was a name.

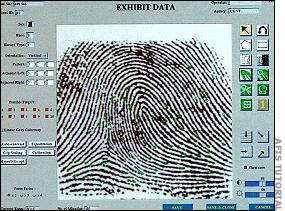

Once the body was carted away to the morgue, a coroner’s technician inked the victim’s hands and pressed his fingertips and palms onto a fingerprint card. The technician then sent the card to LAPD Headquarters at Parker Center, to the Criminal Identification Bureau.

At Parker Center, another technician digitally scanned the dead man’s fingerprint card into a computer and uploaded it to AFIS, the Automated Fingerprint Identification System. Through some mysterious computer wizardry, AFIS can do in minutes what used to take fingerprint examiners days, even weeks, to do: compare a set of fingerprints to millions of others and spit out any matching records.

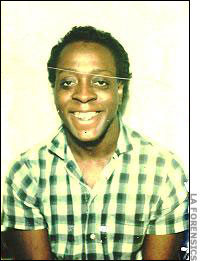

In the case of the dead John/Jane Doe on Compton Avenue, AFIS found a match. The victim was Daniel Williams, age 43, originally from Georgia. Daniel’s rap sheet included arrests for prostitution. He also suffered from drug and alcohol problems. His last known address was the Terminal Hotel at East Seventh Street and South Central Avenue, a half mile from where he was found dead.

In Daniel’s room at the Terminal — a low-rent flophouse where guests had the option of paying cash for a week or a month — detectives found little more than telephone numbers.

Daniel remained an enigma, and who shot him and why remained a mystery.

Just days after Daniel’s murder, LAPD officers from the neighboring Hollenbeck Division found another dead transvestite hooker, this one also killed with a .25 caliber pistol. The Hollenbeck murder scene was just two miles from 12th and Compton.

Were the two killings connected? Could they be the work of a serial killer? Could the victims have been randomly selected?

The surprising second murder threw the Newton Division detectives a curve ball. If the new murder was the work of the same killer, backtracking Daniel’s last 24 hours might be a waste of time.

Most murder victims are killed by someone they know, usually someone close to them. The purpose of developing a reverse timeline for the last day of a victim’s life is to reveal clues about whatever conflict led to the victim being killed.

Stranger murders are different. They are harder to solve because there are no simmering conflicts to uncover. The killing is a random event carried out by someone with no apparent connection to the victim.

At the LAPD Crime Lab, forensic scientists with the Scientific Investigation Division worked as quickly as possible to try to figure out if the two killings were connected. Circumstances indicated a link that science needed to verify. SID’s answer would be another surprise for the detectives.

“Firearms are simply tools and whenever they’re used, they leave behind characteristic tool markings,” says Doreen Hudson, a supervisory criminalist in charge of LAPD’s Firearms Analysis Unit.

Cut into the barrel of every modern firearm is a series of rotating grooves that force a bullet to spin as it travels down the barrel. Much like a football, a bullet travels farther and straighter if it’s spinning during flight. The grooves cut into a barrel leave scratches on the surface of every bullet fired through it. And like fingerprints, the scratches are unique. No two are exactly the same. Under microscopic examination, a spent bullet can be matched to a single firearm by comparing it with a test bullet fired from the same gun.

Likewise, semiautomatic firearms, like the ones used in both the Newton and Hollenbeck transvestite murders, leave distinctive marks on the shell casings of each cartridge. The marks are cause by the firing pin, the thin metal rod that strikes the explosive primer centered in the back of the cartridge case; and by the extractor, an L-shaped piece of metal that catches the rim of the cartridge case and yanks it out of the chamber after the cartridge has been fired. The marks are unique, and, as in the case with spent bullets, under microscopic examination they can be matched to a specific firearm.

In the Newton and Hollenbeck murders, although investigators had not found a firearm, they requested that the Firearms Unit compare the bullets recovered from both bodies and the shell casings found at the two crime scenes to determine if they were fired from the same gun.

When the report came in from the Firearms Unit, detectives in both cases went back to developing their victim timelines. The murders weren’t connected.

“The bullet fragments fired in the Daniel Williams case were compared microscopically to the bullets from the Hollenbeck homicide,” Doreen Hudson says. “Examining the land and groove impressions, we were able to determine that these were fired from different guns.”

Meaning also that the killings were not likely the work of some new serial killer with a thing for transvestites.

In Daniel’s case, investigators were left with little more than what they had found in his apartment, mostly just a collection of telephone numbers.

The detectives subpoenaed the subscriber information for each phone number and contacted the subscribers.

One number came back to a substance abuse center where Daniel had undergone counseling for his drug and alcohol problems. Counselor Kenneth Butler provided the detectives with background information about Daniel. He also put them in touch with a friend of Daniel’s: Joanna, a woman he had met at the rehab center.

When the detectives tracked down Joanna, she told them Daniel had a boyfriend, a man named Ron, whose last name she didn’t know. Daniel and Ron had a rocky relationship, according to Joanna. Daniel had told her he was afraid of Ron.

Suddenly, the mysterious Ron became the investigators’ primary focus, but once again, they were in for another surprise.

Ron had likely started off as one of Daniel’s customers, according to investigators. Sometime later, the relationship had moved from professional to personal. During his infrequent calls back home to Georgia, Daniel even mentioned his relationship with Ron to his family.

“We didn’t know Ron,” Daniel’s sister Pauline Bryant says, “but Danny had mentioned Ron periodically, and we were trying to tell Danny to come home when we found out what kind of character Ron really was, the way (Danny) described him.”

According to Daniel’s friend Joanna, and others at the rehab center, Daniel and Ron’s relationship exploded when Ron found out that Daniel was HIV positive. Before Ron learned about Daniel’s HIV status, the two had been having unprotected sex.

The investigators had to wonder if Ron’s anger at his possible exposure to the virus that causes AIDS would be enough to drive him to kill Daniel.

Revenge, it was as good a motive for murder as any, and one of the most common.

“The only problem that Daniel had with anybody was with this boyfriend…Ron,” Detective Baitx says.

Ron was definitely someone the investigators wanted to talk to. He was, in modern police parlance, a person of interest. The problem was that Ron was himself a mystery. The police couldn’t find anyone who knew his last name or where he lived.

To find Ron, they would have to delve deeper into Daniel’s past.

The detectives assigned to Daniel’s case went back to the victim’s rap sheet. They pulled all of his arrestee information forms, called 510s (pronounced five-tens) after the LAPD form number. In addition to biographical data about an arrested subject, the 510s listed the names and addresses of friends, relatives, associates, and anyone with the person at the time of the arrest.

On one of Daniel’s 510s, the detectives found someone named Ron.

“Ron, in fact, was mentioned on the five-tens as being a boyfriend or an acquaintance of Daniel’s,” Baitx says.

Armed with Ron’s last name and date of birth, detectives started looking for Daniel’s boyfriend. They eventually made their way to another rehab clinic where Ron had been undergoing counseling. Ron wasn’t there, but the detectives left a message for him.

Not long afterward, and much to the detectives’ surprise, Ron called the Newton Division station and asked to speak to the police officers who were looking for him.

“Once he realized that the detectives wanted to talk with him, then he made himself available,” recalls Baitx, who at the time was working on another homicide.

Ron eventually came in for an interview and denied any involvement in Daniel’s murder. Yes, he said, he had been upset that Daniel had concealed his HIV infection. It had added tension to an already rocky relationship, Ron said, but he had not killed Daniel. He was not near 12th and Compton when Daniel was shot. He had been out of town and had been with someone else.

Ron gave the detectives the name of the person he had been with. When they checked out his alibi, they were once again surprised to find out it was true.

So much for Ron as a “person of interest.”

That left the cops with little physical evidence, no eyewitnesses, and now no suspect.

“You’re back to square one,” Baitx says.

With a number of cases to handle, the Newton Division homicide cops originally assigned to investigate Daniel’s murder got pulled away. They caught other assignments and other murders. Daniel Williams’s case got put on a shelf.

“Usually what happens in a case like this, depending on your case load, you work the leads you have,” Baitx says. “If you’ve got viable leads, you work them. In this case you’ve got basically no leads. It was down to nothing. Basically what happens, it becomes a cold case.”

Sometimes, according to Baitx, a detective will keep a cold case file handy as a reminder. A detective with spare time will open the file and run through the leads again. But in South Central Los Angeles, homicide detectives rarely have spare time. There are just too many bodies.

The designation of Daniel’s murder as a cold case didn’t sit well with his sister Pauline Bryant back in Georgia.

She wanted Daniel’s killer found. For years Daniel’s family had known of his lifestyle, but it hadn’t diminished their love for him.

One of four children, Daniel had left home at 16 to find himself and to find a place where he fit in. For years he lived in New York, Pauline says. Then he moved to California. “Los Angeles was the place for him,” she says.

Then he got killed and the case went cold. Pauline says she felt like the police had stopped looking for her brother’s killer, perhaps because of his lifestyle.

“When there were no leads coming in, it was really difficult because it seemed like they had just forgot about it, put it away, and that nothing would ever become of Danny’s case,” Pauline says. “It made me angry.”

As the years passed, Pauline found herself praying that the killer would strike again just so her brother’s case might be reopened.

What Pauline Bryant didn’t know was that science was on her side and that a technological breakthrough was going to give investigators the lead they needed to catch her brother’s killer.

In 2003, the California Department of Justice gave local police departments a grant to reopen old cases in which DNA evidence had been found. The state had just completed a new database containing the DNA records of thousands of convicted felons. The Department of Justice wanted DNA samples from unsolved cases to run through its databank of known criminals.

Back in 1998, the LAPD Crime Lab had not found any sperm or semen in the condom recovered in the Daniel Williams investigation, but SID criminalists had found a tiny number of epithelial cells from both the inside and the outside of the condom. Epithelial cells are skin cells from the lining of mucus membranes such as those found inside the lips, the nose, the rectum, and the genitals.

No DNA profile had been extracted from the cells because there was nothing to compare it to. In 1998, DNA was new to the world of forensic technology and California did not have a DNA database. DNA matching could only be used if investigators developed a suspect from whom they obtained a DNA profile.

An additional problem in Daniel’s case was that there was only enough DNA source material — the epithelial cells — for one try at a DNA extraction. A single test would consume the entire sample.

To even try to remove the DNA material from the sample risked destroying what little physical evidence they had.

Newton Division cold case detectives Salaam Abdul and Dennis Fanning reopened the Daniel Williams case in 2003. Nearly six years had passed since Daniel’s murder.

With the new DNA database up and running in Sacramento, there was a chance that if the LAPD Crime Lab could pull a DNA profile from the slim sample of epithelial cells taken from the condom and send it to the Department of Justice for comparison, they might get a hit. Then again, they might not. And with such a small sample of DNA source material there would be no second chance to develop a DNA profile.

Abdul and Fanning decided to roll the dice. They asked SID to try to extract DNA from the cells, and then they held their breath.

It worked.

Using one of its most experienced criminalists, SID extracted two DNA profiles from the cells found inside and outside the condom. One profile matched Daniel. The other was that of an unknown male.

SID sent the profile of the unknown male to Sacramento.

The results took a week.

On September 10, 2003, they got a match.

“It was what we call a cold hit,” Baitx explains.

The DNA pulled from inside the condom, the DNA of the unknown male, belonged to Erin Jon Richardson, a career criminal who had done six years for armed robbery.

His other arrests included assault with a deadly weapon, drug charges, and forgery. While locked up in 1996, the year before Daniel was killed, prison officials had taken a DNA swab from the inside of Richardson’s cheek to feed into the new database.

“It was a tremendous break,” Detective Abdul says. “It was a tremendous break in the fact that we now had a suspect that we can focus on, we now had a suspect that we can talk to.”

But the case was by no means a slam dunk.

Richardson’s and Daniel’s DNA inside and outside the condom found at the crime scene only proved that they had been there together and that they had sex there, not that Richardson had killed Daniel.

Erin Richardson proved elusive. Abdul and Fanning got word to his parole officer that they were looking for him. Then they contacted Richardson’s mother. She claimed she had not seen her son in years and didn’t know where he was.

The lack of cooperation from Richardson’s mom didn’t surprise Detective Baitx when he heard about it. “Usually with a mother, you always take (what they say) with a grain of salt,” he says. “Mothers want to protect their children no matter how good or bad they are.”

Abdul and Fanning left their business cards with Richardson’s mother just in case. Then the two detectives pressed on with their hunt for their suspect. Good DNA evidence is hard to refute.

“It’s like catching a guy with the gun in his hand, with his fingerprints on it,” Fanning says.

A couple of days after they visited Richardson’s mother, Abdul and Fanning got a surprise telephone call from Erin Richardson.

“Hey, I hear you guys are looking for me,” Richardson said.

The suspect was playing a game and both detectives knew it.

“He was trying to get more information (about) why we were looking for him,” Fanning says, “and he was kind of fishing for how serious it was.”

The detectives mentioned something about traffic tickets. They needed to talk to Richardson, they said, to clear up some minor issues.

“He’s a street-wise guy,” Fanning says. “He’d been arrested on a number of occasions. He knew we were B.S.-ing.”

Richardson said he would come in to talk to the detectives.

Later, an attorney telephoned the two investigators. He said he was representing Richardson. He agreed to bring his client in the following day for an interview. However, the next day the attorney called back. He wasn’t representing Richardson, he said. Apparently Richardson, who had no job, didn’t have any money to pay an attorney.

The detectives executed a search warrant at Richardson’s mother’s house. They were looking for the murder weapon, any .25 caliber ammunition, and, of course, their suspect. The search warrant turned out to be a bust, but it put more pressure on Richardson, further isolating him from his support network.

Abdul and Fanning obtained an arrest warrant for Richardson, charging him with Daniel’s murder. They gave the warrant to the LAPD fugitive squad.

“There was no doubt that Erin Richardson was on the run from the police,” Detective Baitx says. “He was not going to come in. We knew we were going to have to catch him.”

Eighty miles northeast of Los Angeles, in San Bernardino County, lies the city of Victorville. Perched on the southern edge of the Mojave Desert, Victorville has a population of 100,000 and is home to California’s Route 66 Museum.

After months of fruitless searching, members of the fugitive squad finally tracked Richardson to a trailer park in Victorville, where he was staying with a girlfriend.

On September 22, 2004, more than a year after the DNA match that identified Richardson as Daniel’s likely killer, a task force of L.A. cops and fugitive hunters from the U.S. Marshals Service set up surveillance on the trailer where they thought Richardson was staying. Hours later, the task force cops spotted Richardson as he stepped out of the trailer and climbed into a car. As the fugitive drove away, the surveillance team slid in behind his car and pulled him over.

The accused murderer surrendered without a fight.

Shortly after Richardson’s arrest, detectives Abdul and Fanning had their suspect inside a Police Department interrogation room. The DNA hit was powerful evidence, but it didn’t prove murder. They intended to keep the information about the DNA match from Richardson as long as possible. Police interrogations are like a poker game. It’s best to play your cards close to the vest.

During his interrogation, Richardson at first denied even being at the murder scene. He denied ever meeting Daniel. He denied everything. Eventually, Fanning broke the news to Richardson that his DNA had been found on the condom that had been lying under the victim’s body.

The cornered suspect started to explain. “I’m not a bad guy. I mean, I’ve done some things, but whatever I’ve done, you know, whatever I’ve done, I’ll apologize for.”

The detectives turned their hand over slowly, one card at a time.

Fanning explains the strategy: “They lie more and lie more and lie more, and you just show them their lies, and you show them some of the information and some of the evidence that you have, and they finally realize that there’s no sense in lying anymore, that we know the truth.”

Richardson admitted he drank a lot and used drugs regularly around the time of Daniel’s death. He also frequented a strip bar near 12th and Compton. One night while drunk, Richardson cruised through the area in his car and picked up what he thought was a female prostitute.

The detectives pressed him for more details.

“It’s kinda foggy,” Richardson said. “It was a long time ago. I was drunk, you know.”

“What type of sex were you having with this person?” one of the detectives asked.

“Sex was oral…and then regular sex with him,” Richardson said.

After a while the pair got out of the car and started having what Richardson said he thought was vaginal intercourse. While the two of them were bumping and grinding against the fender, Daniel made a remark that Richardson claimed first tipped him that the 6-foot-2-inch, nearly 220-pound prostitute was actually a man.

“The comments were not (from) a woman,” Richardson said. “I can’t even remember the exact words, you know, dialogue or whatever it was.”

Richardson said he went nuts. “I lost it.”

He pulled a gun and shot twice.

“I mean I didn’t try to kill nobody, you know,” Richardson said. “That was, that was purely an accident, you know? Anytime I do anything, I don’t hurt people, it’s accidental. I didn’t really hurt too many people in my life, you know. Whatever I’ve done to anybody you know, (was an) accident.”

Abdul and Fanning had heard the same story countless times. It was a mistake. The gun just went off. I didn’t mean to hurt anybody.

“In Mr. Richardson’s case,” Fanning says, “he seemed very relieved to finally get it off his chest, like he’d been carrying it around for some time.”

Even after Richardson confessed to killing Daniel Williams, he pleaded not guilty and went to trial. He was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter and faces eleven years in prison.

Without breakthroughs in DNA technology and the development of a comprehensive DNA database, the investigation of the murder of Daniel Williams would have almost certainly remained forever locked up in the cold case files of the Los Angeles Police Department. Just another unsolved homicide. Just another uncaught killer.

“Technology caught up with the investigation and solved the case for us,” Baitx says.