All about The Cambridge Spies, by Russell Aiuto — Cambridge Spies — Crime Library

The dark, windowless room in KGB Headquarters held nothing more than a chair, rows and rows of file cabinets, and a long table. If the room had had a window, in the near distance the walls of the Kremlin could have been seen, ablaze with lights. The newly appointed officer sat at the table while a filing clerk piled file upon file upon it. As he went through the dossiers, the KGB official was astonished. Here was the history of four agents who had penetrated the highest reaches of the British intelligence establishment. Everything that Churchill or Roosevelt or Truman had thought had been reported to the Soviets as soon as the three great statesmen had uttered these thoughts. The files were clearly marked: “Transmission to Control, to Beria, to Stalin.” No bureaucracy was to impede the flow of information from these spies. They were too important, their information too reliable. The KGB man smiled. KGB men rarely smiled.

The four were not characters in a spy novel. The KGB official was not an invention of a writer of fiction. They were real. The spies were Burgess, Blunt, Maclean, and Philby.

There have been no more successful, more dramatically impressive spies than a group of Englishmen who all met at Trinity College, Cambridge University in the 1930s. To one degree or another, they were active for the Soviet Union for over thirty years. They were the most efficient espionage agents against American and British interests of any collection of spies in the Twentieth Century. One of them, Kim Philby, served the KGB for almost fifty years.

All four were eventually exposed but — amazingly — never caught. One, Burgess, was a flamboyant, alcoholic homosexual. The second, Blunt, was a discrete homosexual who rose to knighthood as the Royal Curator of Art. The third, Maclean, was a tense, insecure diplomat of ambiguous sexual persuasion. The fourth, Philby — and perhaps the most intriguing of the group — was a dedicated heterosexual who has been called, not inaccurately, the “Spy of the Century.”

Great spies are more interesting in fact than in fiction, more fascinating in reality than in the legends that grow up around them. It is easy to forget that successful spies, by their treachery, are some of the most adept of killers. Their murder victims are faceless, usually never seen by the agents who send them, unwittingly, to their deaths.

“Today, of course, it is well known that Harold Adrian Russell Philby was a Soviet agent within MI-6, a traitor to his own country and a man who betrayed many of the most important secrets of the Western democracies to the Soviet Union. Now Kim Philby is a legend — a demon or an antihero, depending on one’s philosophical bent. Philby himself, or a thinly disguised fictional counterpart, stalks through many modern spy novels.”

— Robert J. Lamphere, FBI Special Agent, 1986

No novel by John LeCarre, Ian Fleming, or Graham Greene can capture the brilliance of this group of Englishmen. No James Bond film, with all of its gadgets and action, can capture the drama of the Cambridge spies.

The Cambridge Four:

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (1910-1963), BBC broadcaster, agent in MI6, secretary to Deputy Foreign Minister, Hector McNeil, British Foreign Office secretary, London, Washington

Anthony F. Blunt (1907-1983), tutor of French, art historian, art adviser to Queen Elizabeth, agent in MI5 during World War Two, “The Fourth Man”

Donald Maclean (1915-1983), Foreign Office secretary, Paris, Washington, Cairo, London

Harold Adrian Russell (“Kim”) Philby (1912-1988), journalist, agent in MI6, “The Third Man”

The Intelligence Organizations:

MI5, the British Office of Counter Intelligence (the equivalent of some of the responsibilities of the American FBI)

MI6, the British Secret Intelligence Service, sometimes referred to as the SIS (the equivalent of the American CIA)

KGB, the Russian Secret Intelligence Service, (formerly the NKVD)

Other principal players:

John Cairncross, Foreign Office secretary, private secretary to Lord Hankey, Secretary for Security, sometimes referred to as “The Fifth Man”

Arnold Deutsch, KGB controller for the Cambridge Four and John Cairncross, 1933-1938

Robert J. Lamphere, FBI, Soviet section

Yuri Modin, KGB controller for the Cambridge Four and John Cairncross, 1947-1953

James Skardon, MI5, interrogator

Michael Straight, American State Department employee

WHO WERE THEY?

Dangerously, the Cambridge Spies invigorate the imagination. As one reads about them, there is an irresistible temptation to cast actors to play their roles in an epic film. One might, for instance, try to capture the cold aloofness of Blunt with an actor of the stature of Paul Scofield. The nervous handsomeness of Maclean might be acted by Liam Niesen. The inscrutability of Philby, complete with stammer, might be played by Derek Jacobi.

The problem with portraying Burgess is that it is difficult to imagine a single actor who could embody all of his contradictory nature. The edgy charm of the handsome Hugh Grant, the seedy world-weariness of Jeremy Irons, and the outrageous cheek of Kenneth Branagh might begin to capture the essence of Burgess.

But such day-dreaming tends to glamorize these four very different, very questionable men. It is an exercise that unnecessarily exhalts them and, at the same time, trivializes their very serious crimes. But it is a temptation difficult to resist.

As early as the late 1920s, the NKVD’s hierarchy had formed a plan for infiltrating Britain’s intelligence establishment. Bright young college men, destined for careers in the Foreign Office or the intelligence agencies, were to be identified. If they were sufficiently Marxist or antifascist, they were carefully cultivated and evaluated. Pamphlet-distributing, young men who were openly members of the Communist Party were of no use to this plan, for they were either too easily identified by their open radicalism as security risks to Britain, or they were more likely working class youth who had little chance of eventually joining the British Establishment. It was, as it turned out, a brilliant strategy.

The Cambridge Spies were four such young men recruited into KGB service during their university years. Two of them, Blunt and Burgess, were members of the “Cambridge Apostles,” a venerable secret society that, in the 1930s, was strongly Marxist. After a visit to Russia in 1933, it appears that Blunt, the oldest (born 1907), was recruited first, directly by the NKVD, and then, in turn, recruited others. He had ample opportunity to be a talent spotter, since he was, at the time, a tutor of French, a subject necessary for any young man contemplating a career in the Foreign Service. Also, as a leading member of the Apostles, he could watch for politically disillusioned younger members as they participated in the political discussions that made up the agenda of the secret society’s meetings. He was not, however, the recruiter of Burgess, Maclean, and Philby, although he knew them well during their undergraduate years.

BLUNT

Anthony Blunt was tall, charming, arrogant, somewhat cold, and a dedicated Communist. He was the grandson of an Anglican bishop, and the son of an Anglican vicar. He was a discrete homosexual, and for a short time he and Burgess were lovers. During the war, Blunt served in MI5 — the British equivalent of the FBI. After the war, he became director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, since he was a specialist in the history of art. Eventually, he became the Royal Family’s art advisor, and was knighted in 1956. Alan Bennett’s play, “A Question of Attribution,” dramatically recreates the relationship between the Queen and Blunt.

He was stripped of his knighthood in 1979, shortly after Margaret Thatcher publicly declared him to have been a Russian spy. He died in 1983.

BURGESS

Guy Burgess was a flamboyant homosexual, strikingly handsome, charming, unpredictable, disheveled, and an intense alcoholic. He was promiscuous and predatory, preferring sexual conquests to emotional commitments. Burgess was the son of a naval officer who failed in attempting to follow in his father’s footsteps. He had none of the characteristics that one would expect in a secret agent. He had many powerful friends and admirers, which served him well in his pursuit of secrets useful to the Soviets. Harold Nicolson, diplomat and writer, describes Burgess a year before his defection in a letter to his wife:

I dined with Guy Burgess. Oh my dear, what a sad, sad thing this constant drinking is! Guy used to have one of the most rapid and acute minds I knew. Now his is just an imitation (and a pretty bad one) of what he once was. Not that he was actually drunk yesterday. He was just soaked and silly. I felt angry about it.

—Harold Nicolson, to his wife, Vita Sackville-West, January 25, 1950

MACLEAN

Donald Maclean (1915-1983) was, like Blunt, tall and good-looking, but had none of Blunt’s icy demeanor and unshakable nerves. His father had been a member of Parliament and Secretary of Education in the government of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. Maclean had had homosexual flings — Burgess claimed to have seduced him at Cambridge — but appeared to be a heterosexual. He was a prodigious worker and a seriously tense alcoholic. After a drunken episode in Cairo, Maclean was sent home to London to “recover” from his “nervous condition.” After a few months of medical leave, he was given the prestigious position of Chief of the American Desk of the Foreign Office. Although the evidence against him in 1951 was slight, both Philby and Burgess knew that Maclean would crack and confess under MI5 interrogation.

PHILBY

Harold Adrian Russell Philby, known as “Kim” after the character in Kipling’s jungle story has been described as both debonair and unkempt, as both unfriendly and ingratiatingly smooth. He was in fact a chameleon who could be whatever the occasion demanded. Philby was so intelligent as a spy that he could detect the difference between “disinformation” meant to deceive the Russians, and secrets that were worth knowing. He had not only incredible instincts, but a certain panache.

He has said that he was recruited as a spy by Edith Tudor-Hart, a British Communist, and by NKVD (later KGB) operative Arnold Deutsch in 1934. In his autobiography, “My Silent War,” — a propaganda document written after he defected to Russia — he said that he, in turn, recruited Burgess and Maclean. The difficulty with Philby’s statements is that he cannot always be believed, and some authors have raised doubts about his recruitment and his recruiting. It is true, of course, that all of them knew each other well at Cambridge.

Philby’s father was a well known authority on Arabia. St. John Philby was at various times a British spy, a diplomat, and an adviser to King Saud. He was eccentric, often critical of the British government, and something of a controlled madman. His son saw little of his father in his youth, greatly admired him, and was somewhat intimidated by him.

Biographers of Philby have speculated that the result of this strong father was a life-long stammer that Kim could control, and sometimes use to his advantage in order to appear ingenuous.

Unlike Blunt and Burgess, Philby was a confirmed and hyperactive heterosexual, marrying four times, with a number of mistresses between marriages. With the exception of his fourth wife, a Russian citizen to whom he was introduced during his life in Russia, and his first wife, a committed Communist — probably an agent — his second and third wives had no idea of his profession. Both wives number two and three were seduced by Philby while married to others, and left their husbands to marry Philby.

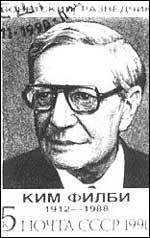

Philby died in 1988, and was recognized before his death with the Order of Lenin, and after death with a postage stamp bearing his likeness and his dates of birth and death.

The patience of the NKVD, and later the KGB, was impressive. Like immature bottles of fine wine, Burgess, Blunt, Maclean, and Philby were set carefully aside to develop into superb vintages. After all, such valuable recruits could not be hurried along in their development as important Soviet agents. Deliberately, the Cambridge Spies were brought along slowly after their recruitment, so that their entry into the British intelligence services was accomplished without doubts ever arising about their loyalty to Britain.

(There were a number of other spies recruited at Cambridge besides these famous four. One of the most important of these others was John Cairncross, whose activities only tangentially interacted with Philby and the other three.)

The Cambridge Four were active spies for different lengths of time. Burgess and Maclean were most productive for about a dozen years, until their defection to Russia in 1951. Philby was at his most productive for about twice that, from about 1940 to 1963 when he too defected to Russia. After defecting, Philby, however, continued to work for the KGB — almost until his death in 1988 — as an adviser and instructor of agents, therefore having a career of almost half a century. Blunt had the longest active, undetected tenure as a spy, about thirty years, until his unmasking and confession, given under a grant of immunity, in 1964.

BEFORE THE WAR

In the late 1930s, the four spies carried out small tasks that established both their reliability to the British and their usefulness to the Soviets. Also, there were those in the KGB who wanted them thoroughly tested, since the KGB was always in fear of having produced double agents.

Blunt quietly recruited, and enhanced his reputation as a highly respectable art historian. Maclean established his credentials as a bright young Foreign Service officer. Burgess and Philby went to some lengths to mask their true political allegiance by becoming pro-Nazi. All four, in effect, assumed the roles of maturing young men now disillusioned with Communism.

Philby, failing to gain entry into the Foreign Service, took a job as a reporter for the London Times, and was first assigned by the Soviets to assist the escape of Communists and anti-fascist Socialists from Austria. There, he met his first wife, Litzi Friedman, a Soviet agent. After his time in Vienna, he went to Spain and reported on the Spanish Civil War for the Times, sending dispatches that were the most favorable to General Franco’s fascists of any that were coming out of that war. On one occasion a car carrying Philby and several other journalists were hit by artillery fire. Two were killed, and Philby was slightly wounded. For his courage under fire, Franco presented him with a medal, further establishing his false anti-Communist credentials.

When war came in 1939, Maclean and Philby (now in France) returned to England. None of the four’s loyalty to the Soviet Union was affected by the Stalin-Hitler Pact of 1939, since they were clever enough to realize that Stalin’s embrace of Nazi Germany was a temporary expedient. Blunt joined MI5, now allowing him to expand his services beyond recruiting and giving him opportunities to transmit secret documents to his KGB control.

THE WAR YEARS

But it was between 1940 and 1945 that the four did most of their first serious damage to Britain and the United States. Authorities differ as to which of the four was the most effective for the Russian cause.

Burgess and Blunt contributed to the Soviet cause with the transmission of secret Foreign Office and MIS documents that described Allied military strategy.

Donald Maclean, particularly during his tenure with the British Embassy in Washington, DC (1944-1948), was Stalin’s main source of information about communications and policy development between Churchill and Roosevelt, and then Churchill and Truman. Although he did not transmit technical data on the atom bomb, he reported on its development and progress, particularly the amount of uranium available to the United States. He was the British representative on the American-British-Canadian council on the sharing of atomic secrets. This knowledge alone gave the Soviet scientists the ability to predict the number of bombs that could be built by the Americans. Coupled with the efforts of Alan May Nunn and Klaus Fuchs, who provided scientific information, Maclean’s reports to his KGB controller helped the Soviets not only to build the atom bomb, but how to estimate their nuclear arsenal’s relative strength against that of the United States.

Kim Philby carried out a variety of assignments. During World War Two, he informed the Russians of the breaking of the Nazi secret code, “Enigma,” by his colleagues at the famous British decoding center at Bletchley Park. The shy, stammering Philby, with easy charm, had no difficulty in being accepted by his cryptanalyst colleagues. In his position in MI6, he was able to identify British agents who were inside Russia to the KGB. Not only did he have access as to who they were, but he was one of the instructors in espionage techniques for many of them.

THE COLD WAR

Maclean was particularly important to Stalin in the years immediately after the war. His continual monitoring of secret messages between Truman and Churchill allowed Stalin to know how the Americans and the British proposed to occupy Germany and carve up the borders of Eastern European countries. Stalin was forearmed with this information not only at the Yalta Conference, but at the Potsdam and Tehran Conferences as well. In 1948, Maclean was transferred to the British Embassy in Cairo.

One of Philby’s most insidious services was to manipulate the failure of Balkan partisans as they attempted to infiltrate behind the Iron Curtain. Philby assisted in the formulation of the plans, then warned the Soviets so that the partisans could be quickly dispatched upon their entry into the country. In effect, it was he who sent dozens of them to their deaths.

Two years later, Philby was posted to Washington, serving as liaison between MI6 and the CIA. He also interacted to some extent with the FBI. In his position as the Embassy Security expert, he had access to all FBI reports shared with the British. Along with Maclean, he was able to let Stalin know that America would not use atomic weapons in the Korean War, nor would MacArthur be allowed to carry the war beyond the Yalu River.

Through his CIA and FBI contacts, Philby learned of the FBI’s breaking of the Soviet code (Venona) and the subsequent identification of a Soviet spy in the British Embassy (Maclean). Thus, he was able to send Burgess to England to warn Maclean of his impending unmasking. Since Burgess had been living in Philby’s house in Washington, Burgess had to assist Maclean’s defection without revealing that it was Philby who had sent him with the warning. If Burgess also defected, Philby would come under suspicion. As it turned out, Burgess fled to Russia with Maclean, and Philby never forgave Burgess.

Burgess, after a brief career as a BBC host of a program about Parliament — wherein he was able to enlarge his acquaintance of important politicians — was most useful to the Soviets in his position as secretary to the British Deputy Foreign Minister, Hector McNeil. As McNeil’s secretary, Burgess was able to transmit top secret Foreign Office documents to the KGB on a regular basis, secreting them out a night to be photographed by his controller and returning them to McNeil’s desk in the morning.

Blunt, in addition to his role as a recruiter of Soviet agents, acted as a go-between for information passed between Burgess and Philby and their Soviet controllers.

Undoubtedly, Maclean’s information was significant in assisting Stalin in his strategy for the Cold War. Blunt and Burgess were important as purveyors of secrets.

But it was Philby, the “Master Spy,” who was the most active, and, considering the risks he took, the most impressive. On several occasions over the years, Soviet defectors suggested that the Russians had a “mole,” never identified but clearly Philby, in MI6. Philby was always able to blunt their accusations, often taking charge of their cases so that he could divert suspicion from himself. One defector, Volkov, prepared to identify Philby, waited for a sum of money to be paid to him before he would reveal his information, and Philby — one of the individuals to be identified by Volkov —was assigned to meet with him. Philby went to the Middle East to meet with Volkov, who somehow had mysteriously disappeared, so that Philby was unable to report what this Soviet defector had to say. Indeed, if it had not been for Burgess’ defection with Maclean, Philby would never have come under suspicion, rising even higher in the hierarchy of MI6. Some authors have speculated that he might even have become the head of this Secret Intelligence Service. With the exception of Burgess’ monumental mistake, Philby said, shortly before his death, that:

“I truly was incredibly lucky all my life. In the most difficult situation when I was sure this was it, the end, no way out, suddenly some stroke of luck would come my way. It was amazing how lucky I was … a lucky life.”

— as told to Borovik, 1988

That may be true, but, as the famous football coach Vince Lombardi once said, “Luck is when preparation meets desire.” Philby was always prepared, and certainly had the desire.

The Cambridge Spies

Defection

The story of the Burgess and Maclean defection, and the subsequent implication of Philby, is a fascinating one of code-breaking, detection, and discovery. In 1949, Robert Lamphere, FBI agent in charge of Russian espionage, along with cryptanalysts, discovered that between 1944 and 1946 a member of the British Embassy was sending messages to the KGB. The code name of this official was “Homer.” By a process of elimination, a short list of three or four men were identified as possible Homers. One was Donald Maclean.

Shortly after Lamphere’s investigation began, Philby was assigned to Washington, serving as Britain’s CIA-FBI-NSA liaison. As such, he was privy to the decoding of the Russian material, and recognized that Maclean was very probably Homer. He confirmed this through his British KGB control. He was also aware that Lamphere and his colleagues had found that the encoded messages to the KGB had been sent from New York. Maclean had visited New York on a regular basis, ostensibly to visit his wife and children, who were living there with his in-laws.

The pressure on Philby now began to grow. If Maclean was unmasked as a Soviet agent, then, were he to confess, the trail might lead to the other Cambridge spies. Philby, now in a very important position in his ability to provide information to the Soviets, might be implicated, if for no other reason than his association with Maclean at Cambridge. Something had to be done.

It is astonishing that Burgess, more and more an unpredictable heavy drinker and indiscreet homosexual, was assigned to the British Embassy in Washington. Why MI6 thought that Burgess could function in the highly charged Cold War environment of Washington, DC is beyond comprehension. As he was ready to leave for his new post in America, Hector McNeil cautioned him to avoid three things : “the race thing,”, contact with the radical element, and homosexual adventuring. “Oh,” said the irrepressible Burgess, “you mean I shouldn’t make a pass at Paul Robeson?” Only the tactless Burgess would have suggested the unlikely prospect of seducing America’s best known black Communist.

Burgess was now staying in a basement apartment with Philby and his family in Washington, and was up to his usual outrageously drunken and predatory homosexual patterns of behavior. Philby thought that he could keep an eye on the unpredictable Burgess by having him live with him. Nonetheless, Burgess was irrepressible, even insulting the wife of a high CIA official at one of Philby’s dinner parties. Concerned that Maclean would be positively identified, interrogated, and, in the process (because of his highly agitated nervous state) confess to MI5, Philby and Burgess concocted a scheme in which Burgess would return to London (where Maclean was now the Foreign Service officer in charge of American affairs). Burgess would then warn Maclean of the impending unmasking. But how could Burgess be sent home to London to warn Maclean without arousing suspicion?

One way was to have Burgess sent home in disgrace, so that his trip to London would be the result of the action of the British Embassy. Whether or not the plan to have Burgess recalled by behaving badly was deliberate, — in his autobiography, Philby claims this — Burgess managed to receive three speeding citations in a single day. He was driving with a companion from Washington, DC to South Carolina to attend a conference. Two of his speeding altercations resulted in a release after his declaring his diplomatic immunity, but the third resulted in an actual citation. He and his “hitchhiker” were detained by the police for several hours, and then released. This last event was communicated to the Governor of Virginia, who informed the State Department, who then informed the British Embassy. Burgess was told that he would have to return to London. If Philby and Burgess had planned his recall, this part of the plan worked beautifully.

Before Burgess left, Philby was explicit in his instructions to Burgess. He was not to defect with Maclean.

The Philby-Burgess plan was for Burgess to visit Maclean in his Foreign Office quarters, give him a note identifying a place where the two could meet — it was assumed that Maclean, now under suspicion and denied sensitive documents, had a bugged office — and Burgess would explain the situation. They met clandestinely to discuss Maclean’s imminent exposure and necessary defection to Russia. Yuri Modin, the Cambridge spies’ KGB controller, made arrangements for Maclean’s defection. Maclean was in an extremely nervous state, and reluctant to leave alone. Modin was willing to serve as his guide, but KGB Central demanded that Burgess escort Maclean behind the Iron Curtain.

In the meantime, MI5 had insisted that Maclean be questioned. They had decided that he would be confronted with the FBI and MI5 evidence on Monday, May 28, 1951.

On Maclean’s birthday, May 25th, the Friday before the Monday that he was to interrogated, Burgess and Maclean fled to the coast, boarded a ship to France, and disappeared. Had Blunt learned of the impending questioning of Maclean, and warned Burgess that the time had come? Blunt never admitted to that, and it is possible that Burgess and Maclean had selected Friday to flee whatever the current circumstances. Both Modin and Philby assumed that Burgess would deliver Maclean to a handler, and that he would return. For some reason, the Russians insisted that Burgess accompany Maclean the entire way. Perhaps Burgess was no longer useful to the KGB as a spy, but too valuable to fall into the hands of MI5.

After Burgess and Maclean were safely in Russia — but only after several weeks — the British government reluctantly admitted that the two men had been Soviet spies. The Soviets, however, refused to acknowledge their past services to the Russian cause, and reported that they were simply “ideological defectors,” unhappy with their imperialist native country. Burgess spent twelve indolent years in the care of the KGB, never learning Russian, indulged with a modest apartment, complete with state-sanctioned live-in lover.

Even in exile, Burgess remained the quintessential Englishman. Alan Bennett, in his play “An Englishman Abroad” dramatized an actual meeting that Burgess had with an English actress who was on tour in Moscow, in which he asked her to provide him with a made-to-measure English suit. While he expressed a desire to return to England because life in Russia was so confining and dull, neither the Russians — who wouldn’t let him return — nor the English — who had no wish to reopen the embarrassment of a prominent MI6 and Foreign Officer’s betrayal — would support his repatriation.

Maclean, unlike the self-indulgent Burgess, integrated himself into the Soviet system, learning Russian, and eventually serving as a specialist on economic policy of the West.

In Washington, when Philby heard of Maclean’s defection, he feigned surprise, although he was of course relieved. When he was informed that Burgess had fled as well, Philby’s surprise was genuine. He had told Burgess that he (Philby) would be placed in jeopardy if he (Burgess) were to defect with Maclean, since the FBI and CIA were well aware that Burgess had been living with Philby and his family. From then on, Philby referred to Burgess as “that bloody man,” and they never spoke again. When Philby arrived in Russia in 1963, Burgess was dying and wished to see Philby, but Philby would have nothing to do with him. Nevertheless, Philby was Burgess’ principal heir.

From the point of the Burgess-Maclean defection, Philby became “The Third Man,” the one who was suspected of having warned them to flee. Philby was sent back to London, accused of having been, at the least, indiscreet in his association with Burgess, and, at the most, having been himself a Soviet agent.

THE THIRD MAN

Now in London, Philby was questioned by MI5. He was able to withstand the grilling with his usual aplomb. Even James Skardon, the famed interrogator who had induced Klaus Fuchs the atom bomb spy to confess, was unable to shake him.

He was however forced to resign from MI6 and given a severance pay. He was now unemployed, with a wife and four children. Many in MI6, an organization that was fiercely competitive with MI5, refused to abandon Philby and they eventually hired him back.

Soon, Philby was in desperate financial straits. Modin arranged to deliver a large sum of money from the Russians. He was to deliver it through Blunt. When Blunt appeared for his late night meeting with Modin, Philby appeared from the shadows. It was the only time, up to that point, that Philby had met his controller. The money was made available to Philby, and his money worries were temporarily addressed.

Philby remained under a cloud. Then, in 1955, a member of Parliament asked the government if it was true that “Harold Philby” was the Third Man. After a time, Harold Macmillan, then the Foreign Secretary, cleared Philby of being the one who warned Maclean and Burgess, saying only that Philby had been dismissed from MI6 because of early Communist affiliations. Philby then held a press conference at his mother’s apartment, and, without a stammer, announced that Macmillan’s statement completely exonerated him.

It is ironic that, eight years later, Macmillan, then Prime Minister, would have his government brought down by a sex-scandal involving one of his cabinet, the infamous “Profumo Affair.” It did not help that it was about the same time that Philby defected to Russia. Thus the man who had cleared Philby now had his governments credibility further diminished. He had not only a ministerial scandal to contend with, but also a major spys defection.

Under the cover of his being a reporter for two English newspapers, MI6 contracted Philby to be their agent in the Middle East, based in Lebanon, where his father, St. John Philby, lived with his Arab wife and two children. For the next six years, Philby continued to provide information for MI6, but, more importantly, for the KGB. Russia had an intense interest in the Middle East, as it sought to expand its sphere of influence into the oil-producing regions.

Then, in 1963, after revelations from a Soviet who had defected to Australia, Philby was confronted by an MI6 colleague, an old friend, who had been sent to Beruit to question him. Philby confessed, but bought himself a few days in order to prepare for his return to London. It was then that he defected to Russia, some twelve years after Burgess and Maclean. There is some suspicion that the British, in order to avoid further embarrassment to an already weakened reputation of their intelligence establishment, actually warned Philby to flee.

After a period of debriefing by the KGB, Philby’s third wife and his children from his second marriage joined him in Moscow. He was able to live comfortably under fairly controlled conditions, but eventually his wife and children returned to England. He carried on a brief affair with Mrs. Maclean — Donald Maclean had become a Russian scholar of Western economics — and after Mrs. Maclean contritely returned to her husband, and then to America (where she still lives), Philby married his fourth wife, a Russian citizen introduced to him by one of his KGB controllers. He spent the rest of his life in Russia as a KGB adviser, lecturer, and trainer of spies. Alan Bennett’s play, “The Old Country,” is about a British spy and his wife in exile in Russia, and has been interpreted as a dramatic representation of Philby’s life as a defector, although Bennett says that the hero of his play could have been any British defector.

Modin is probably accurate in his evaluation of the enigmatic and elusive Kim Philby:

“He [Philby] never revealed his true self. Neither the British, nor the women he lived with, nor ourselves [the KGB] ever managed to pierce the armour of mystery that clad him. His great achievement in espionage was his life’s work, and it fully occupied him until the day he died. But in the end I suspect that Philby made a mockery of everyone, particularly ourselves.”

— Yuri Modin, the KGB controller of the Cambridge Spies, 1994

THE FOURTH MAN

Anthony Blunt had been suspected of being a member of the Burgess spy ring as early as 1951, but particularly after the defection of Philby. In 1964, Michael Straight, an American who had been at Cambridge with the Cambridge spies, confessed to the FBI and MI5 officer Arthur Martin that Blunt had recruited Straight while at Cambridge. Other than meeting with several mysterious figures who may or may not have been Soviet agents, Straight had not really been an active spy.

The admission of the “Fifth Man,” John Cairncross, that he had passed secret papers to the Soviets, and that he was an associate of Blunt, also fired Martin’s determination to catch Blunt. However, the evidence against Blunt was not substantial, so Martin needed a signed confession from Blunt. Blunt gave no indication of being ready to crack, and MI5 did not want the Blunt case to become public. Sir Anthony Blunt, as we shall see, was a member of the Establishment, and, in a sense, a member of the Royal Household.

The only way to obtain a confession from Blunt, and to protect the reputation of MI5, was to offer Blunt immunity from prosecution, which had been done for Cairncross. (Cairncross is still alive, living in France.)

The Attorney General approved, providing that Blunt had not spied for the Soviets after the war. This was a meaningless provision, since Blunt had participated in the defection of Burgess and Maclean, and had undoubtedly maintained contact with Yuri Modin, his KGB controller, until at least 1953.

A meeting between Martin and Blunt was set up for April 23, 1964. Martin outlined the charges made by Straight, and, after informing Blunt that he had been authorized to give him immunity, Blunt said, “It is true.” During the debriefings that followed, Blunt provided information about other spies that were either dead, or already known to MI5 and MI6.

Blunt was then interrogated by Peter Wright, the so-called “Spycatcher.” The only information that Blunt gave Wright was about British Soviet agents who could not be prosecuted, such as Burgess — now dead — and others who were, to one degree or another, invulnerable. By 1972, Blunt had identified twenty-one such spies, none of whom provided new leads or information. He gave conflicting accounts of when and how he was recruited by the KGB. In general, he remained elusive and deceptive until he died.

In 1973, Blunt retired from the Courtauld Institute, praised for his work there and his scholarly efforts as an art historian. Queen Elizabeth, who surely knew of his confession of 1964, had appointed him Advisor to the Queen’s Pictures in 1956, a position he held until his public unmasking by Margaret Thatcher in 1979. He was stripped of his knighthood, and in the next year forced to resign his Cambridge University Trinity College fellowship and his fellowship in the British Academy. He held a most amazing press conference in November, 1979, once again giving almost no concrete information and different accounts of his life as a Russian spy.

He lived quietly and comfortably with his lover, John Gaskin, and died of a heart attack in 1983. Philby was buried with honors in Moscow, Burgess and Maclean were cremated and their ashes returned to England for burial. Blunt, the perfect English gentleman, never left England, and is buried there.

What are we to make of the Cambridge Spies? What is their impact?

It appears that they were not mercenaries. With the exception of a single payment to Philby when he was financially distressed after resigning from MI6, and travel funds for Mrs. Maclean and Mrs. Philby to assist in their joining their husbands in Russia, the Cambridge Four were never paid for their services. The assumption is that they were idealists, rather than spies in for it for personal gain.

There is no question that Philby affected the course of World War II, in that he provided the Soviets with essential information about the intentions of the British and Americans on how they intended to proceed with the war against the Nazis. Further, he and Maclean affected Stalin’s strategy for dealing with post-war matters, since the Russian dictator was fully informed of the alliances designed by Churchill and Truman to thwart the western progression of Communism into Europe. The two of them, Philby and Maclean, contributed to the Cold War tactics that allowed Stalin to know the intentions of the Western bloc. Burgess and Blunt made their contributions through less spectacular but nonetheless important ways, by conveying secret documents and recruiting.

How did they get away with it? The simple answer is that MI5, MI6, and the British Foreign Office were incapable of distrusting four men who “were their own kind.” Past Marxist and Communist affiliations were ignored, first because Marxism was considered antifascist during the war, and, second, because all four belonged to the “old-boy network.” Despite the brilliance of many of the officials in MI5 and MI6, those agencies’ leaders were grossly incompetent in their own internal security policies.

It must be remembered that — whatever their deficiencies of personality — Blunt, Burgess, Maclean, and Philby were highly intelligent individuals. They were more than lucky. They were smart and determined.

A second, lasting influence of their espionage was the loss of confidence between the American and British intelligence communities. It was true that J. Edgar Hoover, even before knowledge of the efforts of the Cambridge Spies, had little trust of the British intelligence services. Still, the effects of Philby, et al, was to further diminish the trust between the CIA, the FBI (already in competition with its sister agency) and the British services, MI5 and MI6. The “special relationship” so important to Anglo-American foreign policy was severely damaged.

The loss of confidence in British intelligence organizations was exacerbated by the clear class distinctions that were evident in the Cambridge Spies case. The special privileges that the intellectual and social hierarchy, represented by Cambridge and Oxford graduates, were able to bring to the administration of government in England proved disastrous to both Britain and America. In truth, the American CIA was much the same, in that its recruits came from the Eastern Establishment, while the FBI, under Hoover, was much more Midwestern and egalitarian. Nonetheless, the view of the British as class-conscious snobs was reinforced by the outrageousness of the success of the Cambridge spies.

American views of the insidiousness of Philby and his colleagues are that their work for the Soviets were serious setbacks for the goals of America in the Cold War. Lamphere of the FBI held the Englishmen in contempt, and the CIA, under James Jesus Angleton, became paranoid after being duped by Philby and Maclean.

The Russians, of course, consider the Cambridge Spies, and Philby in particular, as ideological heroes who advanced the aims of Soviet Russia in an unsettled world that was allied against the goals of Marxism.

The British position is one that moves from annoyance that Philby caused their intelligence community such distress, to that of indifference, described in part by Alan Bennett in his preface to his plays. Bennett’s comments are worth quoting in some detail, since they are typical of the views of many Britons:

“I find it hard to drum up any patriotic indignation over either Burgess or Blunt, or even Philby. No one has ever shown that Burgess did much harm, except to make fools of people in high places. Because he made jokes, scenes, and most of all, passes, the general consensus is that he was rather silly. Blunt was not silly and there have been attempts to show that his activities had more far-reaching consequences, but again he seems to be condemned as much out of pique, and because he fooled the Establishment as for anything that he did.”

Philby, however, is not quite so easy to dismiss, as even Bennett admits:

“It is Philby who is always thought to be the most congenial figure. Clubbable, able to hold his liquor, a good man in a tight corner, he commends himself to his fellow journalists, who have given him a good press. But of all the Cambridge spies he is the only one of whom it can be proved without doubt that he handed over agents to torture and death.”

As for Maclean, Bennet says:

“At the height of the Cold War Maclean’s understanding of Western scruples is said to have had a moderating effect on Soviet policy and the message seems to be that the more we know about each other the less dangerous the world is likely to be.”

Is Bennett’s view a naive view? How serious is espionage? The argument that the world would be better off without secrets, and, therefore, there are no secrets worth keeping, is an interesting and controversial position.

We are left with a spectrum that runs from, on the one hand, disgust for traitorous actions to, on the other, admiration for idealists who were capable enough to get away with them. Disgust and admiration, of course, are in the eye of the beholder. It is clear that the fruits of intelligence are to provide an edge over one’s adversary, even if that edge results in the deaths of one’s enemy. A question that could be raised is: what is the moral difference between the work of the Cambridge Spies and the work of the CIA to bring off the overthrow or assassinations of foreign leaders?

A very recent book by Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Secrecy, deals with these issues from a number of enlightened perspectives. In his introduction to Moynihan’s book, Richard Gid Powers makes the following observation:

“What secrecy grants in the short run — public support for government policies — in the long run it takes away, as official secrecy gives rise to fantasies that corrode belief in the possibilities of democratic government. All because of secrets locked away foolishly and in the end, it would seem, needlessly. Secrecy is a losing proposition. It is, as Senator Moynihan has told us, for losers.”

— Richard Gid Powers, in his introduction to Secrecy, by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, 1998

Whatever the conclusion, there will always be both disgust and grudging admiration for spies who are successful.

As with all good spy and espionage tales, our knowledge of the details and our understanding of the people and events evolve with each new book or article. A recent biography by Miranda Carter, Anthony Blunt: His Lives, reveals a much more complex individual than previous accounts suggest. It is a book that has the advantage of extensive interviews with many who knew Blunt, as well as the large number of documents (some of which are questionable) that have been released since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Kim Philby will forever remain inscrutable, unknowable and mysterious. He was a true spy. Guy Burgess is easily characterized as a narcissistic, strangely attractive and repulsive man. Donald Maclean was, in many ways, an insecure, unstable and ambiguous personality.

That leaves Anthony Blunt, who, after the enigmatic Kim Philby, is the most fascinating of the Cambridge Spies.

Blunt has been the least considered of the group, thought of mostly as a recruiter of young Cambridge graduates into the Soviet spy system, something of a background figure. Carters biography dispels this over-simplification. Indeed, her subtitle His Lives warns the reader that one will be dealing with a complex personality.

While Blunt did indeed recruit for the KGB, he was certainly involved in transmitting secret documents to the Russians. He was actively engaged in espionage, and not a fringe member of the enterprise. However, Carter demonstrates that Blunts work for the KGB was an on-again, off-again participation, sometimes going years between assignments, suggesting a man who was ambivalent about his role as a spy.

In addition to documenting Blunts considerable involvement in spying, Carters biography describes an extremely complex man. She is so convincing in her drawing of the character that the reader is torn between admiration and pity for Blunt. Here was a Cambridge graduate who taught himself art history (at the time, a neglected academic field) and became not only the director and guiding genius of the Courtauld Institute, but the Keeper of the Queens Pictures. While some of his conclusions on certain artists were challenged (and continue to be questioned), the scope of his knowledge, the quantity of his research, and the depth of his scholarship placed him among the most respected art historians in Europe. His fame as a teacher and lecturer was, from evidence presented by Carter, deserved.

At the same time, Carter shows us a man who is lonely, determinedly gay in a society that was not congenial to homosexuality — indeed, for most of Blunts life, it was a crime in England. Despite his tall elegance and his place in elegant post-World War Two British society, he lived a double life, engaging in sex with young men, unable to find a partner who would return his affection, hiding behind his austere and cold public image. There is no question that Blunt and Burgess, particularly in the 30s, were sexual partners, but, as with most of the men Blunt was involved with, never genuine lovers.

Carters brilliant book goes a long way in refuting the superficial myths of John Costellos Mask of Treachery, and provides the record with a very complex and strange member of the Cambridge Spies. It is tempting to arrange these four principal actors by their sexuality — Philby decidedly heterosexual, Maclean ambivalent, Blunt unrequited, and Burgess predatory, but such a taxonomy would shed little light on why they did what they did. Carter does not try to explain Blunts motives, and avoids the trap of facile psychoanalysis that biographers have undertaken with the other three Cambridge Spies. The closest we come to understanding Blunt is through a comment he made to a friend after his unmasking in 1979, when he was more or less isolated in disgrace:

How did you live through all that? [Margaret Wittkower, an old friend, asked Blunt.] You had lunch with the Queen, you were the conservator of her paintings, you knew the whole royal family, you accepted invitations for weekends, you traveled with people of a class that you wanted to destroy. And on the other hand you were an art historian without any interference of your other life. How did you live through that? Blunt lifted the glass of whisky in his hand, and said, With this, and more work and more work.

—- Miranda Carter, Anthony Blunt: His Lives, page 491

The literature on the Cambridge spies falls roughly into four categories, each correlated with a significant historical event.

The first group of books was published as a result of the Burgess-Maclean defections in 1951. The second flurry of books followed Philby’s defection in 1963. The third large number of works resulted from the official unmasking of Blunt in 1979. Finally, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the 1990s have seen a number of books, some of which were based heavily on KGB files and the memoirs of former KGB agents.

Each subsequent group of books reexamined the evidence from the previous group or groups, so that there has been a constant review and reinterpretation of the lives and work of the four principals.

In many respects, the nationalities of the authors correlate with how Philby, et al, are treated. American authors tend to be unimpressed by the talents and accomplishments of the Cambridge spies, and are clearly not charmed by the elegance attributed to them. English writers are more inclined to treat the four spies more kindly. The English are particularly hard on the incompetence of MI5 and MI6, and consider the “old boy” class system of the British establishment as a significant component of the success of the spies.

Recent Russian authors (along with the Englishman Phillip Knightley, who interviewed Philby towards the end of his life) are admiring, extolling the intelligence, dedication, and charm of the Cambridge spies.

However extensive the literature on this case, Philby and Blunt remain inscrutable and unfathomable characters, while Burgess and Maclean seem weak and neurotic.

The Crime Library particularly recommends three recent works. Knightley’s The Master Spy, Borovik’s Philby Files: The Secret Life of Master Spy Kim Philby, and Modin’s My Five Cambridge Friends all cover this bizarre story with the most complete information to date. With the exception of the speculative early works, almost everything written since 1980 has merit, and should not be ignored by the serious student of this case.

BOOKS:

Bethell, Lord Nicholas. 1984. The Great Betrayal: The Untold Story of Kim Philby’s Biggest Coup. Time Books.

Borovik, Genrikh. Philby Files: The Secret Life of Master Spy Kim Philby

Boyle, Andrew. 1979. The Fourth Man. Dial Press.

Brown, Anthony Cave. Treason in the Blood: H. St. John Philby, Kim Philby, and the Spy Case of the Century

Carter, M. 2002. Anthony Blunt. Farrar Straus & Giroux

Cookridge, E.H. 1969. The Third Man: The Full Story of Kim Philby. G.P. Putnam.

Costello, John. 1988. Mask of Treachery. Morrow.

Deacon, Richard. 1986. The Cambridge Apostles: A History of Cambridge University’s Elite Intellectual Secret Society. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Driberg, Tom. 1956. Guy Burgess: A Portrait with Background. Weidenfelt & Nicolson.

Hoare, Geoffrey. 1955. The Missing Macleans. Viking.

Knightley, Phillip. 1986. The Second Oldest Profession. Andre Deutsch.

Knightley, Phillip. 1989. The Master Spy. Knopf.

Lamphere, Robert. 1986. The FBI-KGB War. Random House.

Mann, Wilfrid Basil. 1982. Was There a Fifth Man? Pergamon.

Modin, Yuri. My Five Cambridge Friends

Moynihan, Daniel Patrick. 1998. Secrecy. (Introduction by Richard Gib Powers). Yale University Press.

Newton, Verne W. 1991. The Cambridge Spies: The Untold Story of Maclean, Philby, and Burgess in America. Madison Books.

Nicolson, Harold. 1968. Diaries and Letters, Vol. 3, The Later Years, 1945-1962. Antheneum.

Page, Bruce, Leitch, David, and Knightley, Phillip. 1969. The Spy Who Betrayed a Generation. Sphere Books.

Penrose, Barrie, and Freeman, Simon. 1986. Conspiracy of Silence: The Secret Life of Anthony Blunt. Grafton.

Philby, Eleanor. 1968. Kim Philby: The Spy I Married. Ballantine Books.

Philby, Kim. 1968. My Silent War. Grove Press.

Pincher, Harry Chapman. 1984. Too Secret Too Long. St. Martin’s Press.

Seale, Parick, and McConville, Maureen. 1973. Philby: The Long Road to Moscow. Simon & Schuster.

Straight, Michael. 1983. After Long Silence. Norton.

Sutherland, Douglas. 1980. The Fourth Man. Secker & Warburg.

West, Nigel, ed. 1995. The Faber Book of Espionage. Faber & Faber.

West, Nigel, and Tsarev, Oleg. 1998. The Crown Jewels: The British Secrets at the Heart of the KGB Archives. Harper Collins.

West, Rebecca. 1964. The New Meaning of Treason. Viking.

Wright, Peter. 1987. Spycatcher. Viking.

Yardley, Herbert O. n.d. American Black Chamber. Amercon Ltd.

PLAYS:

Bennett, Alan. 1978. The Old Country. Faber & Faber.

Bennett, Alan. 1988. An Englishman Abroad. (In a single volume entitled Single Spies & Talking Heads). Summit Books.

Bennett, Alan. 1988. A Question of Attribution. (In a single volume entitled Single Spies & Talking Heads). Summit Books.