The Assassination of President William McKinley — The Pan American Expo — Crime Library

Logo

(www.panam1901.bfn.org)

It was a miracle. When people first saw the fantastic lights of the Pan American Exposition of 1901 at Buffalo, that’s what they thought: it was a miracle. The buildings at the Expo were constructed according to a Spanish Renaissance motif, painted in bright pastel colors and covered with thousands of colorful lights. At night, the fairgrounds lighted up the entire sky and could be seen for miles. The Expo was a glimpse into the future world that few ordinary people had ever seen. During that era, there was a passionate interest in new scientific discovery. At the fair, there were exhibitions on science, agriculture, transportation, history and much more. Science was the highlight of the exposition and everywhere, it seemed, there were new advancements in knowledge and learning.

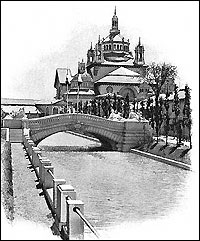

In the center of the Exposition, amidst of a sea of color and fantastic shapes, the massive Electric Tower rose up like a glowing obelisk, a dazzling technological achievement that had spectators gasping in amazement and awe. It was said that electricity would carry America out the darkness of the past and into the light of a better future.

Pan American Expo

(www.panam1901.bfn.org)

Each day, tens of thousands of people from all over the world lined up at the front gates eager to tour the fabulous sights of the Pan Am Expo. They ate chocolate at the Baker’s Chocolate Building, saw the latest in the arts at the Graphic Arts Exhibit, sampled fragrant soaps at the Larkin Soap Building and dined at any one of the 36 restaurants on the fairgrounds. Robert Grant, writing for Cosmopolitan Magazine in 1901 said, “Among the great fairs of the world the Pan American will hold an honorable place…It’s unique and compelling feature is its electric light illumination, which is a superb and masterly achievement.” By the time the Expo closed its gates in the fall of 1901, over 11,000,000 people passed through the turnstiles.

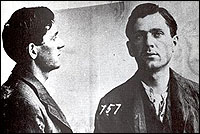

Somewhere in that multitude, in early September, a young man grasped a .32 caliber revolver concealed in his pocket. He was 28 years old, of slim build, wore a slight mustache and had a pale complexion. He roamed the exhibitions only mildly interested in their content and was curiously unimpressed at the wonders of the Expo. Drifting from one display to another, he walked the grounds ruefully with a growing anger at almost everything he saw. Convinced that the government was designed to keep people like him down, he raged within himself and swore that something had to be done to change things. Something had to be done to help the poor workingman break the bonds of poverty. His name was Leon Franz Czolgosz, the son of Polish immigrants. And soon, this disturbed, enigmatic loner, a disciple of the anarchist movement and devoted follower of the political radical, Emma Goldman, would change the course of American history.

To most people, anarchy means violence, but it was not always that way. Although widely believed to endorse a violent overthrow of existing authority, anarchism in its basic form is opposed to violence. Anarchism, as a philosophical doctrine, is the belief that man can only achieve his highest calling by being free from all governmental authority. Derived from a principle of strict independence, anarchy was considered the highest form of human endeavor, unbridled by the restrictions of government and law. Anarchists believe that man is destined to be free and that all government, no matter how democratic, is socially repressive and therefore, anti-human. The birth of modern anarchism is usually traced to the 19th century French writer, Pierre Joseph Proudhon, who believed that the individual is central to society and his independence should be the primary concern of all men.

During the late 19th century, especially in Europe, the ideas of anarchism took hold in labor unions and grew quickly within the socialist movement. But soon, the anarchists broke away from the socialists who they saw as being supportive of more government control, although both groups were opposed to capitalism. However, within the anarchist movement, a violent sect took hold. These disciples were of the opinion that true change could only be achieved through violence and assassination. They believed that capitalists would never change of their own volition. They had to be dragged into a new world where every man would be free and bureaucratic laws that stifle independence would be smashed.

A series of killings took place during this era that was attributed to the violent anarchists. In 1881, Czar Alexander II of Russia and 21 bystanders were killed by an anarchist’s bomb. In Chicago in 1886, during the Haymarket Square Riot, a demonstrator tossed a bomb into the crowd and killed seven police officers. An anarchist stabbed French President Marie Francois Sadi Carnot to death in 1894. And in 1901, an Italian-American anarchist from New Jersey assassinated Humbert I, the King of Italy. These terrorist acts helped the public see the anarchist cause as an attempt to subvert existing authority by violence. And soon, all anarchists were assumed to be potential killers. The newspapers of the time are filled with stories about anarchists and their bloody attacks. In America, especially in the larger cities like Chicago, New York and Cleveland, there was a sort of hysterical fear of anarchists, fueled by a freewheeling, speculative press that knew no bounds to their sensationalized reporting. The New York Journal summarized what it thought to be anarchists’ beliefs in an editorial in April, 1901: “If bad institutions and bad men can be got rid of only by killing, then the killing must be done!”

In 1885, a Lithuanian-born radical named Emma Goldman came to the United States. She originally settled in Rochester, New York where she worked as a seamstress in a clothing factory. Goldman had a lifelong interest in politics and abhorred the evils of capitalism and class structure. She began giving speeches in Cleveland and Chicago praising the anarchist movement. After she gave an emotional lecture in New York City denouncing the Government, Goldman was arrested for inciting a riot. When she was released the following year, she toured Europe giving speeches to aid the Anarchist cause. In America during 1900 and 1901, she gained a reputation as the voice of anarchy and traveled across the country organizing rallies.

On May 6, 1901, Emma Goldman gave a speech in Cleveland. She said to the Chicago Daily Tribune, “Under the galling yoke of government, ecclesiasticism, and a bond of custom and prejudice, it is impossible for the individual to work out his own career as he could wish.” She went on to denounce the present form of government and outlined her vision of the future. “Anarchism aims at a new and complete freedom. It strives to bring about the freedom which is not only the freedom from within but a freedom from without…we demand the fullest and most complete liberty for each and every person to work out his own salvation…” she said. These words are hardly drastic ideas in today’s world. But to a young man in 1901, who spent his entire existence in the iron grip of poverty, who never realized the promise of the American Dream and knew nothing but suffering in his brief life, the words were intoxicating. Leon Czolgosz sat in the Cleveland audience mesmerized by Goldman’s speech. “My head nearly split with the pain…She set me on fire!” Czolgosz said later. He left the lecture hall that day convinced that it was up to him to bring social change to America.

mugshot

Leon Czolgosz (pronounced SHOLGUS) was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1873. His parents, who were of Polish-Russian descent, immigrated to America during the 1860s. His father, a laborer in the construction trade, was frequently out of work. Most of their lives were spent in brutal poverty. At times, there was nothing to eat and the family was often on the road. There were seven children in the Czolgosz family, a lot of mouths to feed when there is no money. Like his brothers, Leon went to work when he was ten. There was no time for such foolishness as education. When Leon was 12, his mother died while giving birth to still another child.

The Czolgosz family eventually made its way to Cleveland and settled down for a time. Leon and two of his brothers got jobs with the American Steel and Wire Company, a large wire-producing mill. They worked there for several years and received higher wages as a reward for their hard work. At his highest point, Leon was making $4 a day, a decent wage for that time. But soon, the mill cut wages and the workers went on strike. Since there were no unions to protect the workers, the mill simply fired all the strikers. It was a pattern repeated many times throughout corporate America. At that time, industry had little respect for and frequently exploited their workers.

In 1897, the Lattimer Mines strike began. Workers went on strike when a new state tax went into effect that further eroded their already low wages. While the miners were engaged in a peaceful march, a struggle broke out between the strikers and the police. The panic-stricken cops opened fire and when the smoke cleared, 19 men were killed and 39 wounded. A criminal trial ended with “not guilty” verdicts for all the defendants. The Slavic community, many of whom were miners, was enraged. Czolgosz saw it as further proof of the failure of government to respond to common people and became embittered by the systemic problems of the labor movement in America. “Yes, I know I was bitter. I never had much luck at anything and this preyed upon me. It made me morose and envious…” he later told police.

Sometime during this period, Czolgosz came into contact with the principles of anarchism. He began to read socialist newspapers and radical magazines that addressed the nation’s social difficulties. He attended political meetings and came to believe there was a great injustice taking place in American society. Czolgosz saw an inequity that allowed the wealthy class to get richer while exploiting the poor. And worse, he believed that it was the structure of government itself that allowed it to happen. He became an anarchist, and believed that people were better off without any sort of government whatsoever.

Eventually, Czolgosz had no other friends except anarchists. “During the last five years, I’ve had as friends anarchists in Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit and other western cities,” he said. He lived for the cause and for years knew nothing else except political rallies and meetings. It was later reported that Leon belonged to an anarchist group known as “Sila” which was based in Cleveland. But during the late 19th and early 20th century, there were many such groups in large cities. “It is estimated there are over a thousand anarchists in the city of Cleveland. They have in the last few years adopted the plan of meeting in small coteries or clubs at the homes of members,” reported the N. Y. Times.

When reporters later interviewed his boss Frank Dalzer at the wire mill, he spoke of Leon’s passion for anarchy. “I know that Leon is, or was, an anarchist. He attended socialist and anarchist meetings very frequently. He is a man of rather small stature, about 26 years of age. The last time I saw him, he had a light brown mustache,” he said. Because of mounting pressures, both financial and emotional, Leon had some type of a mental breakdown in 1898. He returned to his father’s home and became a semi-recluse. He spent his time laying around, sleeping, reading newspapers and radical literature. When it was time to eat each day, Czolgosz took his food away from the table and ate alone, apart from his father and stepmother.

Then on July 29, 1901, an Italian-American immigrant named Gaetano Bresci assassinated King Humbert I of Italy. The news sent shock waves throughout the anarchist movement in the United States. Bresci was an avowed anarchist who told the press he had to take matters into his own hands for the sake of the common man. Czolgosz was elated. He saw Bresci as a hero, a man who had the courage to sacrifice himself for the holy cause. It solidified his hatred for America and convinced him “that it was right to murder anyone branded an enemy of the people by anarchist leaders,” (Nash). When he was arrested months later, cops found a folded newspaper clipping of the Bresci story in Czolgosz’s pocket.

On August 31, 1901, Czolgosz traveled to Buffalo, New York where he rented a room for $2 a week. “I had made up my mind that I would have to do something heroic for the cause I loved,” he later told cops. “I thought of shooting the President but had not yet formed a plan,” he said. He lived in a cramped space above a noisy saloon and left only to visit the Pan American Exposition. The rest of the time, he stayed locked up in his room, brooding over the injustices he saw in life and burning with a hatred for people who caused those injustices. He came to see President McKinley as one of those people, a man who had everything, while he, Czolgosz, the common man, had nothing. On September 5, 1901, Czolgosz bought a .32 caliber Iver-Johnson revolver in downtown Buffalo.

McKinley, portrait

President McKinley established so many “firsts” as a president, it’s difficult to cover them all. He was the first president to ride in an automobile and the first to campaign for political office using a telephone. He once rode in an electric car, although he could not have known that the vehicle was taking him to his deathbed. McKinley is remembered as the first “modern” president, although in reality, he was probably more of a “bridge” between the old and the new.

McKinley was born on January 29, 1843 in Ohio, the “Land of Presidents.” The State of Ohio produced six presidents during the 19th century; more than any other state. He graduated from Allegheny College in Pennsylvania in 1861. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, McKinley immediately signed up with the Ohio Volunteer Infantry. His unit saw a great deal of combat and McKinley fought in battles at Cedar Creek, Opequon and Fishers’ Hill. McKinley also participated in the fearsome clash between Confederate and Union Armies at Antietam on September 17, 1862. On that date, just outside Sharpsburg, Maryland, the bloodiest battle of a brutal war raged for several days. When the carnage was over, 22,000 men lay dead or wounded in the fields next to Antietam Creek. McKinley would never forget that awful experience.

When he returned to Ohio after the war, he became a teacher and, eventually, a lawyer. He ran for Congress on the Republican ticket in 1877 and easily defeated his opponent. McKinley had an outgoing personality and loved to be with people. He liked nothing better than campaigning among crowds, shaking hands and kissing babies. McKinley was also a deeply religious man and attended church every Sunday without fail. In the House of Representatives in Washington D.C, he became a familiar sight and was elected to a total of seven terms as Congressman.

, portrait

He married Ida Saxton, a hometown girl that he fell in love with while at college. But his life was not without tragedy. McKinley and his wife had two children. Both infants died before the age of two, causing Ida to descend into a state of depression and confusion from which she could not escape for the rest of her life. McKinley tried to console her but was overcome with grief himself and became resigned to the tragedy until the end of his days. Because of it, McKinley developed a sense of fatalism, which was obvious to those around him in the White House, even though McKinley appeared buoyant and gregarious in public.

His defining role in history was presiding over the Spanish American War of 1898 during which America gained its most lopsided wartime victory. After the fighting was over, America controlled Puerto Rico, Guam and the 7,200 islands of the Philippines. But the profitable outcome of the war was not without criticism. Many people did not approve of America seizing territory far from its shores but McKinley, who agonized over the decision, finally approved the takeover. When the Pan American Exposition opened in 1901, McKinley, like any other American, wanted to see the wonders at the fair that he read about in the daily newspapers. On September 4, he arrived in Buffalo by special train from Canton, Ohio. He was picked up at the station by John Milburn, director of the Expo and taken to his house where he planned to stay for two days.

At the moment McKinley arrived at the station, a few miles away, in a cramped room above a saloon, a bitter and demented young man toyed with a six shot revolver. Czolgosz wrapped the .32 caliber Iver-Johnson pistol in a handkerchief and placed it in his pocket. Standing in front of the bathroom mirror, he quickly removed it and again returned the gun to his pocket. He practiced this motion over and over. He did not want to fail like he failed at everything else in his young life. He knew he may get only one chance, one moment to change history, one opportunity to make the name Leon Czolgosz fly high forever on the flag of anarchy.

By the early morning of September 5, 1901, the Expo was already full of people. The festive atmosphere was heightened by the expected appearance of the President who was scheduled to give a speech later that day. Over 116,000 people would go through the turnstiles that day and more than 50,000 would hear McKinley’s speech that same afternoon. The exhibitions and sidewalks were full to capacity as at least six different bands played their music to the milling crowds. The President, as always, was eager to go out into the multitude, shaking hands, greeting people face to face. Although his staff always tried to discourage such close-up contact, the president refused to be afraid. “Why should I? No one would wish to hurt me,” was his usual response.

At 12 p.m., the crowds assembled on the Esplanade near the Triumphal Causeway where the President was to give his speech. A few minutes later, an open carriage appeared with the President and the First Lady sitting grandly inside its sparkling exterior. A beaming McKinley stepped down from the carriage and helped his wife onto the pavement. They walked to the dais where he immediately received a tumultuous reception. As the water flowed loudly from the Court of Fountains a short distance away and the vast, dazzling landscape of the Pan American Exposition in its entire splendor lay before him, President McKinley began his speech.

(www.panam1901.bfn.org)

That day, he spoke of the tremendous prosperity of the nation and its limitless potential for the future. The response to the speech was overwhelming and at its conclusion, the crowds broke into waves of applause and cheers. As McKinley stepped off the dais, the people pushed forward trying to get a closer look or to touch his hand. After leaving the Causeway, the President went on a tour of the Expo like any other visitor. As he strolled through the various displays, like the Liberal Arts building, Graphic Arts, and the Transportation building, he came within yards of Leon Czolgosz who was biding his time for a good opportunity. But it was not to be. “I was close to the President when he got to the grounds, but was afraid to attempt the assassination because there were so many men in the bodyguard that watched him. I was not afraid of them…but afraid that I might be seized and that my chance would be gone forever!” the New York Times later reported. McKinley had lunch at the New York State Building and then returned to Milburn’s house in the late afternoon where he would stay the night.

The next morning, Friday, September 6, was a glorious day, an avalanche of sunshine amidst a cloudless blue sky. The President made a leisurely visit to Niagara Falls before noontime with his beloved wife. At about 3 p.m. that day, McKinley and his entourage arrived at the fairgrounds. He was scheduled to give a brief speech and a reception at the Temple of Music, on the southwest side of the Expo in the midst of dozens of flower gardens. John Milburn, George Cortelyou, a long time friend, and several Secret Service officers, accompanied him. Surrounding McKinley were a dozen Buffalo policemen and a squad of U.S. Army soldiers. The reception room at the Temple was a spacious hall containing a large pipe organ and lavishly decorated with potted palms. It made a fine presidential setting. Thousands of people, aware that McKinley would be greeting the public at the Temple of Music, had already gathered outside its doors. The multitude pressed up against the walls and filled the hallways to capacity and beyond. In the forefront of the crowd, Czolgosz stood motionless with his sweating hand grasped firmly around the .32 caliber revolver in his pocket.

At 4:00 p.m. the doors to the auditorium were opened and the public flooded in. There was a thunderous applause as McKinley, with a broad, sincere smile, walked across the room and began to greet each visitor. “Let them come!” the President told his aides. McKinley stood in the center of the room as the crowd, in single file, moved past him, shaking hands as they passed. At precisely 4:07 p.m. while the organ played a Bach sonata, Czolgosz finally reached his target. As the President extended his hand, Czolgosz pushed it aside and pulled out the revolver, wrapped in a handkerchief, from his pocket. Holding the weapon just inches from the President, he fired two quick shots into McKinley’s torso. There was a brief second of silence as the President stared at Czolgosz in amazement.

of President McKinley

“I would have shot more but I was stunned by a blow in the face, a frightful blow that knocked me down and then everybody jumped on me!” Czolgosz said later. Immediately, a wall of people fell upon the assassin. He was knocked to the ground and pummeled by the crowd and the security detail. The people screamed: “Lynch him!” and “Hang the bastard!” As the furious crowd nearly beat the assailant to death, McKinley, his hands clutching his bloody chest, said, “Boys, don’t let them hurt him!”

A panic-stricken crowd quickly encircled the building as the Secret Service struggled to keep control of the scene. Within minutes an electric-powered ambulance arrived to remove McKinley from the scene. As the President was carried from the Temple of Music, his white shirt covered in blood, some spectators screamed in horror, others fainted.

Unknown to anyone at the time, one bullet had never penetrated flesh. It had bounced off a button on McKinley’s jacket and was lodged inside his clothing. The other bullet had passed through his stomach, damaging the pancreas and a kidney. The physical damage to the organs alone was not enough to cause death, but the infection caused by the path of the bullet and the quality of the medical care given to the President would take its toll.

At 4:18 p.m., McKinley arrived at the emergency hospital at the Expo. An examination by doctors determined that the wound was indeed of a serious nature and required extensive surgery. The room was not equipped to handle such a procedure but necessity dictated immediate action. While he lay on the examining table, the bullet that was caught in his clothing fell to the floor. Ether was administered to the president and as he drifted off, McKinley said a prayer, “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done…” As the afternoon sun began to fade, one of the attendants held up a mirror to reflect light into the wound so the surgeon could see what he was doing.

When the abdomen was opened, the doctors found that the stomach was severely damaged by the bullet which had passed completely through and lodged somewhere near the spine. Although the doctors undoubtedly tried as best they could, the bullet could not be found. McKinley was a big man; his size and girth did not help the situation. During the operation, someone at last had put together an electric light over the table. Another attempt was made to locate the bullet by probing into the President’s abdominal cavity. Still it could not be found. Ironically, not too far away, in the Technology Building, a new invention called an X-Ray machine sat idle. Amidst concern over the patient’s weakened condition, the procedure was halted. The incision was closed, but the surgeon neglected to drain the wound. The President was then taken back to the Milburn house for recuperation.

Mrs. McKinley stayed by his side, devastated by the attempt on her husband’s life. She had already lost two small children and now her husband lay dying before her eyes. She spent the next few days in confusion, shock and disbelief. The President later regained consciousness and, typical of his character, attempted to console those around him.

Meanwhile, the news of the assassination attempt spread throughout the world. Telegrams from every national leader poured into the White House and the Pan American Expo. When it was learned that the assassin was an anarchist, people became angry. There was a great deal of speculation about an organized plot to kill the President. Emma Goldman was tracked down in Chicago a few days later where she was arrested on suspicion of murder. Her defiant attitude and comments to the press did not improve matters. When asked about Czolgosz, she championed the anarchist cause.” Am I accountable because some crack-brained person put a wrong construction on my words? …I think Czolgosz was one of those down trodden men who see all the misery which the rich inflict upon the poor, who think of it, who brood over it and then, in despair, resolve to strike a great blow for the good of their fellow man!” Goldman said.

Over the next few days, the President’s condition actually improved and reports from the Milburn residence indicated growing optimism. Doctors also stated that the wound seemed to be healing properly and that the patient’s pulse was back to normal. “The crisis has passed. The strain on the heartstrings of the Nation has been relieved…President McKinley will fully and speedily recover from the wounds inflicted upon him by the Anarchist Czolgosz,” said the New York Times on September 10. But the truth was bleak. Unknown to his physicians, internal infection had already set in and flowed through McKinley’s bloodstream. He was dying and no one knew it. Ironically, the headline in the Times on September 11 read “President Will Get Well Soon.”

By September 13, the President was decidedly worse and sinking fast. Gangrene had developed along the path of the bullet. Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, who was in the backwoods of the Adirondack Mountains, was quickly notified of the situation. He rode out of the forest on horseback and boarded a train to Buffalo. McKinley slipped in and out of a coma over the next few hours. During the afternoon of September 14, McKinley awoke long enough to comfort his family and friends who stood vigil beside his bed. “Good bye all. It is God’s way. His will, not ours, be done. Nearer my God to Thee!” he said softly. A few minutes later, as his beloved wife wept by his side and sobbed “I want to go too, I want to go too!” McKinley died. Shortly afterwards, the forceful and charismatic Theodore Roosevelt, at age 42, was sworn in as the youngest President in American history. It would be his destiny to usher in the 20th century with his own swaggering style of bravado and a towering ego that, in a very real sense, was a reflection of America itself.

The murder trial of Leon Czolgosz began on September 23, 1901 in the Supreme Court building in downtown Buffalo in front of Justice Truman C. White. The District Attorney who handled the case was Thomas Penney. Generally, there was little doubt of the outcome of the trial although nearly everyone respected his right to have one. “There can be no defense for his crime, and no question of his conviction, and nothing will be permitted to stop a speedy judgment,” reported the N.Y. Times on September 15. The nation’s press descended upon the Buffalo jail and “hammered away at him, trying to get him to admit that he had been inspired by reading Hearst papers,” according to Tebbel and Watts. But the trial went according to schedule. In the early 20th century, court proceedings were handled at a much quicker pace than today. Justice, it was thought, must move fast, especially in cases where the guilt was obvious. A trial was thought of as just a formality and any delays whatsoever by the defense were frequently treated with contempt.

Former Judge Loran L. Lewis was head of the defense team and even he had reservations about his job. As part of his opening statement, he apologized for defending Czolgosz. “When the circumstances of my selection were told to me, I was extremely reluctant to accept,” he told the court. After Justice White thanked him for his remarks, jury selection began. By early afternoon, a complete jury with alternates was chosen and sworn in. At 2:30 p.m., testimony began and by the end of the day, the jury heard testimony from Expo employees, three physicians who attended McKinley, the medical examiner who performed the autopsy and several witnesses. The small courtroom was packed with spectators and police who followed every word. There was also concern for the safety of Czolgosz who could be shot at any moment. Every spectator was carefully scrutinized by police, as were newspaper reporters and anyone else who entered the court.

The next morning, the trial opened promptly at 10 a.m. Witness James Quackenbush, a member of the reception committee at the Temple of Music was called to the stand.

“Tell us what you know,” asked D.A. Penney.

“Immediately there were two shots. The prisoner was borne to the floor. Secret Servicemen, Officers Ireland and Foster were also in the group scrambling on the floor about the defendant,” Quackenbush replied. The .32 caliber Iver-Johnson revolver was introduced into evidence and held up as proof of Czolgosz’s guilt (This weapon still exists today and is on display at the Nottingham Court Museum in Buffalo, New York.)

Each witness who was at the Temple of Music identified Czolgosz, who sat at the defense table with a blank stare. Czolgosz also made a complete and detailed confession to police after his capture, which was introduced in court and accepted as evidence. Czolgosz said that he had been watching McKinley for 3 or 4 days waiting for a good time to shoot the President. He also signed a lengthy written statement in which he explained why he committed the murder. “I killed President McKinley because I done my duty. I don’t believe one man should have so much service and another should have none,” he wrote.

At 3:10 p.m. District Attorney Penney summed up the case for the prosecution. He spoke in grand terms of President McKinley. “A man so great that he could raise his hand and save his own assassin, a man who could shake the hand of even the very worst man you could imagine,” he said. At 3:20 p.m., Judge White gave his charge to the jury. “You must consider all this evidence that the people have submitted to you. You must consider it fairly and without prejudice,” he told the court. At precisely 3:51 p.m., the jury left the courtroom to deliberate the verdict.

About a half hour later, at 4:26 p.m. the jury announced that it were ready.

“And what is your verdict?” asked the judge.

“That the defendant is guilty of murder in the first degree!” the jury foreman replied. Czolgosz sat in his chair unmoved. He displayed no emotion and seemed bored with the proceedings. The entire trial, from jury selection to verdict, had taken 8 hours and 26 minutes.

On September 26, Justice White addressed Czolgosz: “The sentence of this court is that the week beginning October 28, 1901, at the place, in the manner and means prescribed by law, you suffer the punishment of death. May God have mercy on your soul. Remove the prisoner!” Czolgosz never made a sound nor did he stir an inch. As police guarded him closely, he was escorted out of court and taken to a hidden room. Authorities were very concerned about street mobs breaking into the jail and lynching the prisoner. Throughout the trial, there were continued threats of mob violence and the court was eager to get Czolgosz out of Buffalo.

On September 27, he was taken to Auburn State Prison, which at that time still had an electric chair. Although he arrived at Auburn at 3:00 a.m., there were hundreds of angry people waiting for him at the train station. Czolgosz was attacked and dragged off the train by crowds of people who beat him relentlessly as the security detail struggled to keep control. Cops swung their blackjacks at the rioting crowd who seemed determined to lynch the terrified prisoner. He was dragged kicking and screaming into the prison where guards fired rifles above the crowd to fend them off. Eventually, Czolgosz was tossed into a cell, bloodied and beaten unconscious.

For the next few weeks, he remained in his cell. He was allowed no visitors and he was not permitted to go outside even for exercise. The prison warden, J. Warren Mead, was determined that Czolgosz receive no notoriety for his crime. He would not let reporters inside the prison nor would he allow any photographs. Dr. Carlos McDonald of New York City, one of the physicians who had examined Czolgosz and concluded he was sane, was scheduled to be at the execution. He made a request to Warden Mead to remove Czolgosz’s brain after death to perform a detailed examination. The request was denied because the warden was afraid it would increase publicity. “I cannot allow anything to go away from the prison that will in any way continue this man’s identity or notoriety…my present plan is not to allow any portion of the man, his clothing or even the letters he received to leave this place,” said Warden Mead to the N.Y. Times.

On the morning of October 29, 1901, at 7:00 a.m., just 45 days after McKinley died in Buffalo, Czolgosz was removed from his cell and brought to the execution chamber. It was a rather small, gray room with heavy steel doors. There were several rows of seats for witnesses and the windows on each side of the walls were high up near the ceiling. As the witnesses sat into their seats, Warden Mead addressed the audience: “You are here to witness the legal death of Leon F. Czolgosz. I desire that you keep your seats and preserve absolute silence in the death chamber no matter what may transpire.”

In a corner of the room was a closet-like structure that concealed the control panel for the electrical current. Electrician Edwin Davis, the state’s executioner, who also traveled to other prisons to administer the death penalty, manned the controls. The chair itself was a large, ordinary piece of furniture. It had huge, wide leather straps for the chest area and legs. Hanging down from the ten-foot ceiling was a coiled wire that attached to a helmet, which was placed over Czolgosz’s head. The attendants fastened the straps over his body as a third guard wet a specially made sponge and placed it under the helmet. This was done to ensure a solid connection and to enable the current to do its deadly work. During this era, when killing by electricity was still new, executions were frequently mishandled. Many of those were due to poor preparation and a failure to understand that electricity needed secure contact to travel freely.

As the guards made the final adjustments on the straps, Czolgosz spoke to them. “I killed the President because he was an enemy of the good people of the working people. I am not sorry for my crime!” he said. The final strap was placed over his chin and fastened to the chair to prevent his head from jerking forward during the application of the current. “I’m awfully sorry I could not see my father,” he said through clenched teeth.

Precisely at 7:12 a.m., Warden Mead gave the signal and the electrician pulled the lever that sent 1,700 volts soaring through the body of the prisoner. Czolgosz jerked forward, throwing his chest hard against the restraining straps that looked as if they would snap from the pressure. His hands tightened up into fists and his whole body trembled at once. His face became a beet red and a tiny wisp of steam emanated from under the helmet. The current remained at 1,700 volts for one full minute until the electrician gradually lowered the amount to zero. Then, after a wait of a few seconds, he turned up the power again to 1,700 volts for ten seconds more. The lifeless body of Czolgosz again jumped forward as the chair noticeably creaked. The current was then shut down completely. Dr. McDonald stepped forward from the witness row to examine the prisoner. Although he felt no pulse, he suggested another application of current. He stepped back and again the electrical current was applied. After a second brief examination, Dr. McDonald happily announced, “Gentlemen, the prisoner is dead!” Czolgosz was the 50th person to die in the electric chair in New York.

After a three-hour autopsy during which his brain was carefully examined by a team of pathologists from New York City, they issued this statement: “The examination revealed a perfectly healthy state of all the organs, including the brain.” Under the supervision of Dr. McDonald, Czolgosz’s body and all its parts were then placed in an extra-thick pine box coffin. The remains were to have been covered with quicklime but research indicated that lime would not erode the body sufficiently. A special acid was imported into the prison prior to the execution for this purpose. As several witnesses cowered in the corner of the autopsy room, the acid was poured into the coffin. The body was then covered with straw and the coffin was sealed. Research conducted by Warden Meade indicated that the body would fully dissolve in about 24 hours. Czolgosz’s clothing and personal effects were burned shortly afterwards. The letters that were written to the prison during the time he was on Death Row were saved for a while and then also destroyed. The Warden was adamant about not making Czolgosz into some kind of martyr for the anarchist cause.

The Superintendent of Prisons, Cornelius V. Collins, had this to say: “Just consider that within six weeks from the death of his distinguished victim Czolgosz has been executed for his crime!” Warden Meade told reporters: “The execution was one of the most successful ever conducted in the State.” And executioner Edwin Davis, who already executed four other prisoners that year, had this to say: “The body showed eight amperes of resistance. That is a little more than would be given by a larger or stouter man where the current could have more chance to percolate.”

Waldek Czolgosz, Leon’s father came to the prison later that day to claim the body, but he was too late. He declined a visit to the grave but insisted upon a death certificate in order to claim some life insurance held by his son. He left the prison with the certificate and was never heard from again.

Leon Czolgosz fit the classic profile of the 20th century American assassin: a mentally disturbed loner in his twenties, under-achiever with little or no social bonds who believes he is destined for bigger things in life. Men who share those same characteristics committed almost all the political assassinations in America during the last two centuries. And like each one, John Booth, Charles Guiteau, Lee Oswald, Sirhan Sirhan and James Earl Ray, Leon Czolgosz changed the course of history through the barrel of a gun and his name will be etched forever in the annals of crime, murder and infamy.

Memorial

A special thanks to Professor Susan Eck of S.U.N.Y. at Buffalo who maintains The Pan American Exposition 1901 website at http://www.panam1901.bfn.org

Chicago Daily Tribune, “Speech That Prompted Murderous Assault on the President,” September 7, 1901.

Evans, Harold, The American Century. Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

Grant, Robert. Cosmopolitan, September, 1901 from http://www.panam.bfn.org

Leech, Margaret, In the Days of McKinley. Harper and Brothers Publishers. 1959.

Morgan, H. Wayne, William McKinley and His America. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1963

Nash, Jay Robert, Encyclopedia of World Crime. Wilmette, IL: Crimebooks, Inc. 1990.

New York Times:

September 8, 1901,”The Assassin Makes a Full Confession,” p. 1

“Assassin Known as a Rabid Anarchist,” p.4; September 11, 1901

“Emma Goldman is Arrested in Chicago,” p. 3; September 24

“Assassin Czolgosz on Trial in Buffalo,” p. 1; September 25, 1901

“Czolgosz Guilty,” p. 1; October 28, 1901,

“Plans For Execution of Assassin Czolgosz,” p. 1; October 30, 1901

“Assassin Czolgosz is Executed at Auburn,” p. 3.

Olcott, Charles S., The Life of William McKinley. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916.

Tebbel, John and Watts, Sarah Miles (1985), The Press and the Presidency. Oxford University Press. 1985.

Wilson, Colin, True Crime. NYC: Carroll and Graf Publishers Inc.1998.