Jack the Ripper, the most famous serial killer of all time — Perennial Thriller — Crime Library

Jack the Ripper! Few names in history are as instantly recognizable. Fewer still evoke such vivid images: noisome courts and alleys, hansom cabs and gaslights, swirling fog, prostitutes decked out in the tawdriest of finery, the shrill cry of newsboys – and silent, cruel death personified in the cape-shrouded figure of a faceless prowler of the night, armed with a long knife and carrying a black Gladstone bag.

—Philip Sugden, The Complete History of Jack the Ripper

From Hell

By today’s standards of crime, Jack the Ripper would barely make the headlines, murdering a mere five prostitutes in a huge slum swarming with criminals: just one more violent creep satisfying his perverted needs on the dregs of society. No one would be incensed as were the respectable families of the pretty college students that were Ted Bundy’s victims, or the children tortured and mutilated by John Wayne Gacy. We have become a society numbed by horrible crimes inflicted upon many victims.

Why then, over a hundred years later, are there allegedly more books written on Jack than all of the American presidents combined? Why are there stories, songs, operas, movies and a never-ending stream of books on this one Victorian criminal? Why is this symbol of terror as popular a subject today as he was in Victorian London?

Because Jack the Ripper represents the classic whodunit. Not only is the case an enduring unsolved mystery that professional and amateur sleuths have tried to solve for over a hundred years, but the story has a terrifying, almost supernatural quality to it. He comes from out of the fog, kills violently and quickly, and disappears without a trace. Then, for no apparent reason, he satisfies his blood lust with ever-increasing ferocity, culminating in the near destruction of his final victim, and then vanishes from the scene forever. The perfect ingredients for the perennial thriller.

When Charles Cross walked through Whitechapel’s Buck’s Row just before four in the morning Friday, August 31, 1888, it was dark and seemingly deserted. It was chilly and damp, not unusual for London even in the summer, especially before dawn. He saw something that looked like a tarpaulin lying on the ground before the entrance to a stable yard.

As he walked closer, he saw it was a woman lying on her back, her skirts lifted almost to her waist. He saw another man walking the same way. “Come and look over here,” he asked the man, assuming that the woman was either drunk or the victim of an assault. As they tried to help her in the darkened street, neither of the two men saw the awful wounds that had nearly decapitated her. They fixed her skirt for modesty’s sake and went to look for a policeman.

A few minutes later, Police Constable John Neil happened by the body while he was walking his beat. From the light of his lantern, he could see that blood was oozing from her throat, which had been slashed from ear to ear. Her eyes were wide open and staring. Even though her hands and wrists were cold, Neil felt warmth in her arms. He called to another policeman, who summoned a doctor and an ambulance.

Neil awakened some of the residences in the respectable neighborhood to find out if they had heard anything suspicious, but to no avail. Soon, Dr. Rees Llewellyn arrived on the scene and examined the woman. The wounds to her throat had been fatal, he told them. Since parts of her body were still warm, the doctor felt that she had been dead no longer than a half-hour, dying perhaps minutes after Neil had completed his earlier walk around that area.

Her neck had been slashed twice, the cuts severing her windpipe and esophagus. She had been killed where she was found, even though there was very little blood on the ground. Most of the lost blood had soaked into her clothing. The body was taken to the mortuary on Old Montague Street, which was part of the workhouse there. While the body was being stripped, Inspector Spratling discovered that her abdomen had been wounded and mutilated. He called Dr. Llewellyn back for a more detailed examination.

The doctor determined that the woman had been bruised on the lower left jaw. The abdomen exhibited a long, deep jagged knife wound, along with several other cuts from the same instruments, running downward. The doctor guessed that a left-handed person could have inflicted these wounds very quickly with a long-bladed knife. Later, the doctor was not so sure about the killer being left-handed.

There have been several theories about how the wounds were inflicted. Philip Sugden makes a persuasive case:

If (the victim’s) throat were cut while she was erect and alive, a strong jet of blood would have spurted from the wound and probably deluged the front of her clothing. But in fact there was no blood at all on her breast or the corresponding part of her clothes. Some of the flow from the throat formed a small pool on the pavement beneath (her) neck and the rest was absorbed by the backs of the dress bodice and ulster. The blood from the abdominal wound largely collected in the loose tissues. Such a pattern proves that (her) injuries were inflicted when she was lying on her back and suggests that she may have already been dead.

Identification would not be easy. All she had on her was a comb, a broken mirror and a handkerchief. The Lambeth Workhouse mark was on her petticoats. There were no identifying marks on her other inexpensive and well-worn clothes. She had a black straw hat with black velvet trim.

The woman was approximately five feet two inches tall with brown graying hair, brown eyes and several missing front teeth.

But later, as news of the murder spread around Whitechapel, the police learned of a woman named “Polly,” who lived in a lodging house at 18 Thrawl Street. Eventually, a woman from the Lambeth Workhouse identified the victim as Mary Ann Nichols, age 42. The next day her father and her husband identified her body.

Polly had been the daughter of a locksmith and had married William Nichols, a printer’s machinist. They had five children. Her drinking had caused their marriage to break up. For the most part, Polly had been living off her meager earnings as a prostitute. She still had a very serious drinking problem. Every once in awhile, she would try to get her life back together, but it never worked out. She was a sad, destitute woman, but one that most people liked and pitied.

The inspector in charge of the investigation was a police veteran named Frederick George Abberline, who had been on the force 25 years, most of which had been spent in the Whitechapel area.

The murderer of Polly Nichols left nothing behind in the way of witnesses, weapon or any other type of clue. None of the residents nearby heard any kind of disturbance, nor did any of the workmen in the area notice anything unusual. Even though Polly had been found very shortly after her death, no vehicle or person was seen escaping the scene of the crime. At one point, suspicion focused upon three horse slaughterers who worked nearby, but it was proven that they were working while the murder occurred.

At the time of Polly Nichols’ death, the inhabitants of London’s Whitechapel area had already heard about a number of attacks on women in that neighborhood. Whether or not one or more of these attacks was perpetrated by the man who later became known as Jack the Ripper is controversial. However, in the minds of the people of Whitechapel, most of these crimes were linked indisputably.

On Monday, August 6, 1888, several weeks before Polly Nichols’ murder, Martha Tabram, a 39-year-old prostitute, was found murdered in George Yard. The time of death was estimated to be 2:30 a.m. She had been stabbed 39 times on “body, neck and private parts with a knife or dagger,” according to Dr. Timothy Killeen’s post-mortem examination report. There was no indication that the throat had been slashed or the abdomen extensively mutilated. With the exception of one wound that had been delivered with a strong knife with a long blade, such as a dagger or bayonet, many other wounds had been inflicted with a penknife.

According to another prostitute, Mary Ann Connelly, known as Pearly Poll, she and Martha had been together in the company of two soldiers until a few hours before Martha was killed. The police took Poll to check out the soldiers at the Tower garrison, but the soldiers she identified were cleared of the crime. A constable who had been on duty in the vicinity of George Yard also saw a soldier in that area around the time of Martha’s death, but this soldier was never properly identified.

Some months earlier, Emma Smith, a 45-year-old prostitute, was attacked on April 2, 1888, at seven o’clock in the evening, within 100 yards of where Martha Tabram was found. Her head and face were badly injured and a blunt instrument had been rammed into her vagina. She told the woman at her lodging house that several men robbed and assaulted her.

near where Emma Smith was assaulted

While these incidences of violence so close together in Whitechapel were linked so firmly in the minds of their neighbors, the crimes themselves were very different. Tabram was probably murdered by one individual, while several men assaulted Smith. Robbery was clearly the motive of the Smith assault, but not the murder of Tabram. The nature of the wounds inflicted was quite different. Thus, it is not likely that the same assailant was responsible for both crimes. Only the Tabram murder bears any similarity to the work of the man eventually known as Jack the Ripper.

This street is in the East End. There is no need to say in the East End of what. The East End is a vast city…a shocking place…an evil plexus of slums that hide human creeping things; where filthy men and women live on…gin, where collars and clean shirts are decencies unknown, where every citizen wears a black eye, and none ever combs his hair.

-Arthur Morrison, Tales of Mean Streets

The East End of London was, in Victorian England, a place outcast from the city, both economically and socially. Some nine hundred thousand people lived in this teeming slum. Here, the cattle and sheep would be herded through the streets of Whitechapel to the slaughterhouses nearby where they were bludgeoned, bleating with fear and pain. The streets were stained with blood and excrement. Rubbish and liquid sewage gave the area a horrible smell.

inspection

Most of the inhabitants lived in tenement houses under deplorable conditions:

Every room in these rotten and reeking tenements houses a family, often two. In one cellar a sanitary inspector reports finding a father, mother, three children, and four pigs! In another room a missionary found a man ill with small-pox, his wife just recovering from her eighth confinement, and the children running about half naked and covered with dirt. Here are seven people living in one underground kitchen, and a little dead child lying in the same room. Elsewhere is a poor widow, her three children, and a child who has been dead thirteen days.

-Andrew Mearns, The Bitter Cry of Outcast London

For the most part, the people who lived in this East End were the working poor, those who worked occasionally, those who did not work at all, and criminals. Most people lived on a day-to-day basis. More than half of the children born in the East End died before the age of five. Of those who survived, many were mentally and physically handicapped.

Prostitution was one of the only reliable means through which a single woman or widow could maintain herself. The police estimated that in 1888 there were some 1,200 prostitutes in Whitechapel, not including the women who supplemented their meager earnings by occasional prostitution.

There were over 200 common lodging houses in Whitechapel, accommodating almost 9,000 people. The sleeping rooms were long rooms with rows of beds, often infested with vermin and insects. If a woman had not earned enough money that day to pay for a bed for the night, she would have to find someone who would let her sleep with him in return for sexual favors. Otherwise she slept on the street.

boarding house

However, despite various urban renewal efforts and the improvement in environmental conditions brought about by the Jewish settlers, Whitechapel was still an area known for its poverty and crime. In the squalor of crowded tenements, narrow darkened slum streets and alleys, the Whitechapel murderer had found a perfect place for his work.

Jack the Ripper

Dark Annie

Because the people of Whitechapel firmly believed that the deaths of Martha Tabram, Emma Smith and Polly Nichols were connected, there was a great deal of pressure upon the police to bring the criminal(s) to justice. Three theories were entertained: (1) a gang of thieves was responsible, such as the men who robbed and assaulted Emma Smith,; (2) a gang extorting money from prostitutes penalized the three women for failing to pay; (3) a maniac was on the loose.

Considering how poor the victims were, the first two theories were not very plausible, so the final theory became popular. The East London Observer commented on the Tabram and Nichols murders:

The two murders which have so startled London within the last month are singular for the reason that the victims have been of the poorest of the poor, and no adequate motive in the shape of plunder can be traced. The excess of effort that has been apparent in each murder suggests the idea that both crimes are the work of a demented being, as the extraordinary violence used is the peculiar feature in each instance.

A request was made of the Home Secretary for a reward to be offered for the discovery of the criminal. Henry Matthews, the Home Secretary, had no idea at this point what he was dealing with, and declined to offer a reward, laying responsibility at the feet of the Metropolitan Police.

Today, even with all the techniques of modern forensic science and psychology, a serial killer is a major challenge for a metropolitan police force. Some serial killers will never be caught, regardless of the sophistication and skill of the authorities in that jurisdiction. London’s Metropolitan Police, in Victorian times, was operating almost completely in a knowledge vacuum, with no modern forensic tools available to them. Fingerprinting, blood typing and other staples of forensic technique were not yet developed for police use. Even photography of victims was not a usual practice. There was no crime laboratory at Scotland Yard until the 1930’s.

Police today have developed elaborate profiling techniques to identify serial killers, and have amassed a database of information with which forensic psychologists and psychiatrists can determine the kind of individual perpetrating the crime. In 1888, the police were ignorant of sexual psychopaths. They had seen nothing like the Ripper crimes in England in their experience.

While police were searching for the killer of Polly Nichols, a story surfaced about a bizarre character named “Leather Apron.” This man required prostitutes to pay him money or he would beat them. The Star claimed the man was a Jewish slipper maker of the following description:

From all accounts he is five feet four or five inches in height and wears a dark, close-fitting cap. He is thickset and has an unusually thick neck. His hair is black, and closely clipped, his age being about 38 or 40. He has a small, black moustache. The distinguishing feature of his costume is a leather apron, which he always wears…His expression is sinister, and seems to be full of terror for the women who describe it. His eyes are small and glittering. His lips are usually parted in a grin which is not only not reassuring, but excessively repellent.

With all this publicity, including the fear of mob violence, “Leather Apron” went into hiding.

Annie Chapman, known to her friends as “Dark Annie,” was a pathetic woman. She was essentially homeless, living at common lodging houses when she had the money for a night’s lodging, otherwise roaming the streets in search of clients to earn a little money for drink, shelter and food.

She was 47 when she died, a homeless prostitute. But her life had been much different in 1869, when she was married to John Chapman, a coachman. Of the three children they had, one died of meningitis and another was crippled. The stress of illness and the heavy drinking of both husband and wife caused the breakup of their marriage. Things became much worse for Annie when John died and she lost the small financial security his allowance had provided her. The emotional shock of his death was just as bad as the financial loss and she never recovered from either.

Suffering from depression and alcoholism, she did crochet work and sold flowers. Eventually she turned to prostitution, despite her plain features, missing teeth, and plump figure. For the most part, she was very easy going. However, a week before her death, she got into a fight with a woman over a piece of soap and Annie was struck on the left eye and on her chest.

On Friday, September 7, 1888, Annie was told her friend that she was feeling sick. Unknown to her, she was suffering from tuberculosis. “I must pull myself together and get some money or I shall have no lodgings,” she told her friend Amelia.

Just before two in the morning on Saturday, September 8, a slightly drunken Annie was turned out of her lodging house to earn money for her bed. Later that morning, she was found several hundred yards away in the backyard of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields.

29 Hanbury Street was just across from the Spitalfields market. Seventeen people made the building their home, five of which had rooms overlooking the site of the murder. Of those five or so with rooms overlooking the crime scene, some had their windows open that night.

Spitalfields Market opened at 5 a.m., so there were many other people gathered that morning, people who had businesses in the building at 29 Hanbury, preparing for the opening of the market. Residents were leaving for work as early as 3:50 a.m. The streets around the market were filled with the commercial vehicles delivering to the marketplace. John Davis, an elderly carman who lived with his wife and three sons at 29 Hanbury, found Annie’s body just after 6 a.m. He noticed that her skirts had been raised up to her pelvis. He went immediately to get help and returned with two workmen. By the time a constable was called, everybody in the house had been awakened.

Yet, amazingly enough, even though the sun rose at 5:23 that morning, and so much traffic was present at that early hour, no one heard any suspicious disturbance or cry, nor was anyone seen with bloody clothing or weapon. There was clean tap water in the backyard where Annie was found, but the murderer did not use the water to wash the blood from his hands or knife. Also amazing was the risk that the murderer took in this daylight crime.

Phillips

Dr. George Bagster Phillips, veteran police surgeon, was called to the spot and described what he saw for the inquest:

I found the body of the deceased lying in the yard on her back…The left arm was across the left breast, and the legs were drawn up, the feet resting on the ground, and the knees turned outwards. The face was swollen and turned on the right side, and the tongue protruded between the front teeth, but not beyond the lips; it was much swollen. The small intestines and other portions were lying on the right side of the body on the ground above the right shoulder, but attached. There was a large quantity of blood, with a part of the stomach above the left shoulder…The body was cold, except that there was a certain remaining heat, under the intestines, in the body. Stiffness of the limbs was not marked, but it was commencing. The throat was dissevered deeply. I noticed that the incision of the skin was jagged, and reached right round the neck.

Dr. Phillips estimated that Annie Chapman had been dead approximately two hours. The absence of any cry heard by the residents of 29 Hanbury could be explained by the evidence that she was strangled into unconsciousness and immediately thereafter had her throat slashed.

Chapman at the scene

She had been murdered where she was found. While there was no sign that Annie had fought off her attacker, there was a strange occurrence that Dr. Phillips noted near the feet of the corpse. Annie had apparently kept in her pocket a small piece of cloth, a pocket comb and a small-tooth comb, all of which had appeared to be purposely arranged in some order.

An envelope containing two pills was found near her head. On the back of the envelope were the words Sussex Regiment. The letter M and lower down Sp were handwritten on the other side. There was a postmark that said London, Aug. 23, 1888. Also, a leather apron was found, along with some other trash around the yard.

The testimony that Dr. Phillips gave at the inquest gave a more detailed view of the ferocity of the murder. The murderer had grabbed Annie by the chin and slashed her throat deeply from left to right, with the possible failed attempt to decapitate her. This was the cause of death. The abdominal mutilations, described in the September 29 edition of the Lancet, were post mortem:

The abdomen had been entirely laid open; that the intestines, severed from their mesenteric attachments, had been lifted out of the body, and placed by the shoulder of the corpse; whilst from the pelvis the uterus and its appendages, with the upper portion of the vagina and the posterior two-thirds of the bladder, had been entirely removed. No trace of these parts could be found, and the incisions were cleanly cut, avoiding the rectum, and dividing the vagina low enough to avoid injury to the cervix uteri. Obviously the work was that of an expert – of one, at least, who had such knowledge of anatomical or pathological examinations as to be enabled to secure the pelvic organs with one sweep of the knife.

At the inquest, Phillips said, “The whole inference seems to me that the operation was performed to enable the perpetrator to obtain possession of these parts of the body.” This police surgeon with 23 years of experience was very surprised that the mutilations had been done so skillfully and in what must have been a short period of time, saying that he could have not done such work in less than fifteen minutes and more likely an hour.

Coroner Wynne E. Baxter agreed in his summation:

The body has not been dissected, but the injuries have been made by someone who had considerable anatomical skill and knowledge. There are no meaningless cuts (like in the Tabram murder). It was done by one who knew where to find what he wanted, what difficulties he would have to contend against, and how he should use his knife, so as to abstract the organ without injury to it. No unskilled person could have known where to find it, or have recognized it when it was found. For instance, no mere slaughterer of animals could have carried out these operations. It must have been someone accustomed to the post-mortem room.

Phillips conjectured that the murder instrument was not a bayonet or the type of knife used by leather workers, but rather a narrow, thin knife with a blade between 6 and 8 inches long. The kind of knife used by slaughtermen and surgeons for amputations could have been such an instrument.

Abrasions on Annie’s hands indicated that her rings had been forced off her. Later, from conversations with Annie’s friends, police were able to determine that Annie wore cheap brass rings, which may have been mistaken for gold.

Inspector Abberline, who was in charge of the Polly Nichols murder, was instructed to help with the Chapman murder, which was in Spitalfields, a different police jurisdiction. However, the lead inspector was Joseph Chandler of the Metropolitan Police’s H Division. There seemed common agreement among the inspectors that the same man who killed Polly Nichols also killed Annie Chapman.

The Chapman investigation was just as frustrating as the Nichols investigation. The physical evidence – the leather apron, a nailbox and a piece of steel – were owned by Mrs. Richardson, one of the residents, and her son. The envelope with Sussex Regiment seal on it was widely sold to the public at a local post office. Furthermore, a man at Annie’s lodging house saw her pick up the envelope from the kitchen floor to put her pills in when her pillbox broke.

Extensive conversations with the associates of Annie Chapman yielded neither good suspects nor any reasonable motive for the crime. Nor was there any suspicious person found escaping the scene of the crime.

However, the investigation was not entirely fruitless and three important witnesses were found, one of which almost certainly caught a glimpse of the murderer. The first witness, John Richardson, was Mrs. Amelia Richardson’s son. Between 4:45 and 4:50 on the morning of the murder, he visited 29 Hanbury to check the locks on the cellar in which Mrs. Richardson kept her tools and goods for her packing case enterprise.

He opened the yard door and sat down on the step to cut a piece of leather from his boot that had been hurting his foot. As it was beginning to get light outside, he could see that the cellar locks had not been tampered with while he sat fixing his boot. He could also see that at that time, there was no body of Annie Chapman in the backyard. “I could not have failed to notice the deceased had she been lying there then,” he said at the inquest.

Another witness, Albert Cadosch, living next door to 29 Hanbury Street, testified that he heard voices coming from the backyard of 29 Hanbury Street just after 5:20 a.m. The only word he overheard was No. A few minutes later, around 5:30 a.m., he heard the sound of something falling against the fence.

the inquest

The most important witness was Mrs. Elizabeth Long, who was coming to the Spitalfields market and passed through Hanbury Street when she heard the Black Eagle Brewery clock strike 5:30. She saw a man and a woman talking “close against the shutters of No. 29.” Mrs. Long identified Annie Chapman in the mortuary as the woman who had been facing her as she passed down Hanbury Street. Unfortunately, the man Annie was conversing with, who was almost certainly her killer, had his back to Mrs. Long. She did her best to describe him in her testimony to Coroner Wynne E. Baxter:

Some of the merchants in the area were quick to sense the growing anti-Semitic fever and took action to contain it. They formed the Mile End Vigilance Committee, which was primarily composed of Jewish businessmen. George Lusk, a building contractor and vestryman in his local church, was elected to head this committee of 16 prominent local citizens. This committee, far from being the vigilante group that some had claimed, was closer to an organized “neighborhood watch.” Samuel Montagu, who was the Jewish Member of Parliament for the Whitechapel area, offered a reward for the capture of the Whitechapel killer, an action sanctioned by the Mile End committee.

In a week or so, the bawdy nightlife of Whitechapel surged back to its normal pitch. There were just too many people whose daily subsistence depended upon prostitution and other forms of evening entertainment to let the pace lapse for long.

While Whitechapel was unsatisfied with the lack of results of the police investigation, it was hard to fault the police for the quantity of work that was produced. On Tuesday, September 11, a few days after the death of Annie Chapman, John Pizer, the famous “Leather Apron,” was arrested.

Despite attempts by his family to portray Pizer as a victim of malicious rumors, there was sufficient evidence to show Pizer was an unpleasant character with at least one documented case of stabbing, for which he served six months at hard labor. The allegations of bullying and extorting money from prostitutes were never proven. The East London Observer described in a not altogether unbiased view, Pizer’s testimony to Coroner Baxter:

He was a man of about five feet four inches, with a dark-hued face, which was not altogether pleasant to look upon by reason of the grizzly black strips of hair, nearly an inch in length, which almost covered the face. The thin lips, too, had a cruel, sardonic kind of look, which was increased, if anything, by the drooping dark moustache and side whiskers. His hair was short, smooth, and dark, intermingled with grey, and his head was slightly bald on the top. The head was large, and was fixed to the body by a thick heavy-looking neck. Pizer work a dark overcoat, brown trousers, and a brown and very much battered hat, and appeared somewhat splay-footed.

When Baxter asked Pizer why he went into hiding after the deaths of Polly Nichols and Annie Chapman, Pizer said that his brother had advised him to do so.

“I was the subject of a false suspicion,” he said emphatically.

“It was not the best advice that could be given to you,” Baxter returned.

Pizer shot back immediately. “I will tell you why. I should have been torn to pieces!”

The fact that Pizer was an unpleasant character did not make him the Whitechapel murderer. First of all, he had alibis for the times at which Polly Nichols and Annie Chapman were murdered. When Polly was killed, Pizer was at a lodging house, which was corroborated by the proprietor. When Annie was killed, he was afraid to be seen and was staying with relatives, a story which was corroborated by several people. Secondly, he lacked the skill to carve up Annie Chapman and remove her uterus.

Pizer was released, but a number of others were picked up and questioned. Some were just eccentric and drunken characters that shot off their mouths about the murders; others were insane. Few were worthy of prolonged investigation, either because they lacked the medical skills or because they had alibis for the time the women were murdered. Often the alibis consisted of confinement in asylums or jails.

Insanity and medical qualifications became the key factors in sorting out suspects. Another factor was foreign origin, recalling Mrs. Long’s testimony in the Annie Chapman murder. The focus on medical knowledge led the police well beyond the reaches of Whitechapel, into the middle and upper classes of London, as the eccentric and violent behavior of some surgeons and other physicians came into question.

Louis Diemschutz, a Russian Jew, was driving his pony cart to Dutfield Yard, off Berner Street in Whitechapel, at 1 a.m. on Sunday, September 30, 1888. Diemschutz and his wife lived at the International Working Men’s Educational Club (IWMC) and took care of the club’s premises. The IWMC was a club composed primarily of Eastern European Jewish Socialists.

In his spare time, Diemschutz sold costume jewelry at various outdoor markets and was returning from this commercial enterprise when he pulled into the club yard. As he did so, he saw an object on the ground near the wall of the club building. He struck a match and saw that it was a woman.

Diemschutz rushed into the club and got a young member to help him. When they saw that the object was a woman with a stream of blood running from her body, the two men ran screaming for a policeman.

A few minutes later, Police Constable Henry Lamb and his associate were on the scene. Lamb felt warmth in the woman’s face, but could detect no pulse. His associate went immediately to look for a doctor. PC Lamb did not see any signs of a struggle, nor were the woman’s clothes unduly disturbed, like the earlier victims whose skirts had been raised up past their knees.

Dr. Frederick Blackwell was on the scene at 1:16 a.m. with his assistant, who had arrived a few minutes earlier. He detailed his findings at the inquest:

The deceased was lying on her left side obliquely across the passage, her face looking towards the right wall. Her legs were drawn up, her feet close against the wall of the right side of the passage. Her head was resting beyond the carriage-wheel rug, the neck lying over the rut…

The neck and chest were quite warm, as were also the legs, and the face was slightly warm. The hands were cold. The right hand was open and on the chest, and was smeared with blood. The left hand, lying on the ground, was partially closed, and contained a small packet of cachous (breath sweeteners) wrapped in tissue paper.

The appearance of the face was quite placid. The mouth was slightly opened… In the neck there was a long incision …(which) commenced on the left side, 2 inches below the angle of the jaw, and almost in a direct line with it, nearly severing the vessels on that side, cutting the windpipe completely in two, and terminating on the opposite side…

Dr. Phillips, the police surgeon, had joined Blackwell at the scene of the crime. Between the two of them, the estimate of her time of death was between 12:36 and 12:56 a.m.

The police continued to investigate the death scene, but nothing in the way of clues or weapon was found. They did determine, however, that the chairman of the IWMC had walked through the yard around 12:40 a.m., some 20 minutes before the body was found, and had seen nothing suspicious, nor was anyone standing around. Likewise, Diemschutz had not seen anyone when he pulled into the yard at 1 a.m.

While the police were coping with yet another Whitechapel murder, a most extraordinary thing happened just a quarter of a mile away in Mitre Square. Some 24 yards square, it was generally a respectable area surrounded by commercial buildings and warehouses, with very few residences. At night, when the businesses were closed, Mitre Square became a dark and somewhat secluded area.

Watkins

Mitre Square was on the beat of Police Constable Edward Watkins of the City Police. He had been through the square at 1:30 a.m. and all was quiet. He came around again at 1:44 a.m., some 45 minutes after the discovery of the woman in Dutfield’s Yard. Again, it was quiet and deserted. When he shined his lantern in one corner of the square, he made a horrible discovery.

He described it to the coroner a few days later: “I saw the body of a woman lying on her back with her feet facing the square, her clothes up above her waist. I saw her throat was cut and her bowels protruding. The stomach was ripped up. She was lying in a pool of blood.”

He ran over to one of the businesses on the square to get George Morris, a retired constable who worked as a night watchman. With his whistle, he got help from a couple more policemen. The City Police then began to search the area to see if the killer could still be found.

Brown

At 2:18, Dr. Frederick Gordon Brown got to the scene of the crime and made his examination. The victim’s abdomen had been ripped open and she had fearful mutilations to her face. The “body was quite warm; no death stiffening had taken place; she must have been dead most likely within the half hour,” he later said at the inquest.

There was no money found on the corpse and there was no evidence that she had struggled with her killer.

site, rear of Mr. Taylor’s shop

and carriageway into Mitre St.

All in all, the Mitre Square event was pretty amazing, if for nothing more than the aggregation of police in that particular area at the time of the crime. In addition to Watkins and Morris, another policeman, whose beat included a perimeter of Mitre Square, reached the square at about 1:42 a.m. Like the other policemen, he heard nothing and saw nobody. Also, there was a police constable who lived on the square who slept through the entire thing.

As it turned out, the murderer got his victim into the square, killed her, carved her up silently, and completely escaped, in the space of fifteen minutes. But the night was not over yet.

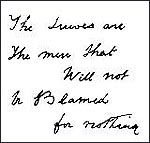

At 2:55 a.m., Constable Alfred Long found a piece of a bloody apron lying in the entrance to a building in Whitechapel’s Goulston Street. Just above the apron, written in white chalk on the black bricks of the archway was the wording:

The Juwes are

The men That

Will not

be Blamed

For nothing.

Charles Warren

The piece of bloody apron came from the woman who had been murdered in Mitre Square and the police believed that the writing was the killer’s. A constable was left to guard the writing and some preparations were made to have the writing photographed. But before the writing could be photographed, it was ordered destroyed in a highly controversial move by Sir Charles Warren, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. Warren explained his rationale for an action which would be criticized for over a hundred years:

The writing was on the jamb of the open archway…visible to anybody in the street and could not be covered up…I do not hesitate to say that if the writing had been left there would have been an onslaught upon the Jews, property would have been wrecked, and lives would probably have been lost.

How this murderer was able to accomplish two such murders in such a short time, particularly with the mutilations of the second victim, without being seen by the police or anybody and then, when the area was in a heightened state of alarm, create the chalk writing on the archway, is nothing short of amazing.

After the murder in Dutfield’s Yard, the police conducted house-to-house interviews with the people in that neighborhood. Any bystanders who had aggregated to watch the police conduct their examination were interrogated.

The dead woman was approximately five feet two inches tall with a very light complexion and dark brown curly hair. She was dressed predominantly in black, with a red rose decorating her jacket. Nothing to identify her nor anything of value was found in her pocket.

After a few red herrings, she was identified as Elizabeth Stride, who was born in 1843 in Sweden. She had most likely come to England as a domestic worker. She had made up a story that she was a survivor of the Princess Alice boating disaster that had occurred in 1878, claiming that her husband and two children had drowned. This story was useful in getting charity from the Swedish Church in London, and in generally arousing sympathy for her. The real story is that her husband, John Stride, was a survivor of the Thames River tragedy, but he had died later in the poorhouse.

She lived with a laborer named Michael Kidney for three years before her death. She was a well-liked woman who people nicknamed “Long Liz.” While she may have occasionally prostituted herself, for the most part she earned a living by doing sewing or cleaning work. Once in a while, she became drunk and boisterous, an event noted more than once in the magistrate court.

She left her lodging house in the early evening and did not tell anyone where she was going. She had a small amount of money in her pocket that she had earned by cleaning rooms. At the time she left the lodging house, there was no rose on her jacket.

Dr. Phillips testified that the woman died because of her throat wounds. This time there was no indication of strangulation, although the killer may have caught Liz by her scarf and pulled her backwards while cutting her throat. Dr. Blackwell characterized the killer as someone “who is accustomed to use of a heavy knife.”

This time, many witnesses came forward to claim that they had seen Liz just before her death. One of them was Constable William Smith, who was walking his beat around Berner Street and saw Liz talking to a man around 12:30 in the morning, shortly before her death. The man that Smith saw was around thirty years old with dark hair and moustache. His complexion was also dark. He estimated that the man was about five feet seven. This man was dressed in a dark felt deerstalker hat with a black diagonal cutaway coat, white collar and tie. He had a good-sized parcel in his hands.

Another important witness was Israel Schwartz, who gave this story to Inspector Swanson:

At 12:45 a.m. Israel Schwartz of 22 Helen Street…saw a man stop and speak to a woman, who was standing in the gateway. The man tried to pull the woman into the street, but he turned her round & threw her down on the footway & the woman screamed three times, but not very loudly. On crossing to the opposite side of the street, he saw a second man standing lighting his pipe. The man who threw the woman down called out apparently to the man on the opposite side of the road ‘Lipski’ & then Schwartz walked away, but finding that he was followed by the second man he ran as far as the railway arch but the man did not follow so far…

Schwartz identified the body as that of the woman he had seen and thus describes the first man who threw the woman down: age about 30, height five feet 5 in., complexion fair, hair dark, small brown moustache, full face, broad shouldered; dress, dark jacket and trousers, black cap with peak, had nothing in his hands.

Second man, age 35, height 5 feet 11 inches, complexion fresh, hair light brown, moustache brown; dress, dark overcoat, old black hard felt hat wide brim, had a clay pipe in his hand.

Police took the evidence of Constable Smith and Israel Schwartz very seriously. Two other important witnesses surfaced. William Marshall lived at 64 Berner Street and had been standing near the site of the murder about 11:45 p.m., approximately an hour and a quarter before the event occurred. He identified Liz as talking to a man who he described as middle-aged, wearing a round cap with a small peak, “like what a sailor would wear,” about 5 feet 6 inches tall, rather stout, dressed like a clerk, and speaking like an educated man. He was not able to get a look at the man’s face. While Marshall’s description of the man with Liz is similar to Smith’s and Schwartz’s, Liz could have been talking to someone entirely different than her killer an hour and a quarter before the murder.

James Brown came forward with another sighting of Liz that night at 12:45 a.m., minutes before her death. When he reached the intersection of Berner and Fairclough Streets, he saw Liz talking to a man. He overheard her say, “Not tonight, some other night.” The man he described was about 5 feet 7 and wearing a very long dark overcoat. Brown’s timing is open to question since he was estimating rather than looking at any clock.

The descriptions of the man talking to Liz Stride given by Smith, Marshall and Schwartz may refer to the same man. Unfortunately, it did not help the police find this suspect.

Square

The woman murdered in Mitre Square was easier for the police to identify since she had some pawn tickets on her that, when publicized, brought forward John Kelly, the man she had been living with for seven years at a lodging house at 55 Flower and Dean Street.

Catharine Eddowes, called Kate by all who knew her, was a very friendly and happy woman, known for her good spirits and singing. She, like the other victims, had a periodic drinking problem, which led to quarrels with her companions and family.

Kate was born in 1842. Her parents died when she was young and the household was dispersed. When she was 16, she fell in love with Thomas Conway and went to live with him as his common-law wife. They lived together some 20 years and produced three children. Conway’s physical abuse and Kate’s drinking caused the couple to break up in 1880. The next year, she met John Kelly and remained his lover for the rest of her life. Her friends were adamant that Kate was not a prostitute, but there is some reason to believe that she did occasionally prostitute herself, perhaps when under the influence of alcohol.

The evening before her death, Kate told Kelly she was going to visit her daughter to borrow some money. Kelly warned her about the Whitechapel killer and told her to come back early. “Don’t you fear for me. I’ll take care of myself and I shan’t fall into his hands,” she reassured him.

Kate never got to her daughter’s house, but she did find some money – enough to get stinking drunk and land in the jail at the Bishopsgate Street Police Station. She slept off her over indulgence until 12:30 a.m., when she asked to be allowed to go. Shortly afterwards, Constable Hutt let her go. She asked him what time it was and he told her it was just about one o’clock.

“I shall get a damned fine hiding when I get home then,” she told him.

“And serve you right,” Hutt told her. “You have no right to get drunk.”

Mitre Square was a mere eight-minute walk away.

As in the deaths of Polly Nichols and Annie Chapman, Kate’s throat had been deeply slashed from left to right and the resulting wound was the cause of death. According to Dr. Brown’s testimony:

The abdomen had been laid open from the breast bone to the pubes …The intestines had been detached to a large extent …(and) about two feet of the colon was cut away…The peritoneal lining was cut through and the left kidney carefully taken out and removed. The left renal artery was cut through. I should say that someone who knew the position of the kidney must have done it…The womb was cut through horizontally, leaving a stump of ¾ of an inch. The rest of the womb had been taken away with some of the ligaments. The vagina and cervix of the womb was uninjured.

sketch by Federick

Foster

The face was very much mutilated. There was a cut about ¼ of an inch through the lower left eyelid dividing the structures. The right eyelid was cut through to about ½ inch. There was a deep cut over the bridge of the nose extending from the left border of the nasal bone down near to the angle of the jaw of the right side. The tip of the nose was quite detached from the nose.

Several other cuts were sustained on the face, plus the right ear lobe had been completely severed and had fallen from her clothing when she was taken to the morgue.

An important witness surfaced — Joseph Lawende, who left the Imperial Club with two friends at about 1:35 a.m. The men saw a couple conversing at Church Passage near Mitre Square. Lawende described the young man as dressed in a dark jacket, wearing a deerstalker’s hat. The man was young, medium height and with a small, fair-colored moustache. He did not see the woman’s face, but identified Kate’s clothing. Nine minutes after this sighting, Kate Eddowes was murdered.

What about the chalk writing found over an hour later on Goulston Street under which lay a portion of Kate’s bloody apron? “The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.”

Philip Sugden discusses three feasible interpretations of this message. First is that the message was not written by the murderer and just happened to be where the killer dropped or placed the bloody piece of apron.

A second possible interpretation offered by Walter Dew, a Whitechapel police officer in 1888, is that the message represents “the defiant gesture of a deranged Jew, euphoric from the bloody ‘triumphs’ in Dutfield’s Yard and Mitre Square.” One of the many problems with this interpretation is that, according to the Acting Chief Rabbi Hermann Adler, “I do not know any dialect or language in which ‘Jews’ is spelled ‘Juwes.'”

The third possible interpretation was that the message was “a deliberate subterfuge designed to incriminate the Jews and throw the police off the track of the real murderer.” This third interpretation was much favored by Scotland Yard and the Jewish community.

Whoever the author of the message was, it yielded very little in the way of identifying its writer. The belief of some authors that the word “Juwes” is a Masonic term is disputable. “It is a mystery why anyone ever thought that ‘Juwes’ was a Masonic word,” wrote Paul Begg, an expert on the Ripper murders.

Hundreds of letters allegedly from the murderer were sent to the police, news agencies, and individuals associated with solving the crimes. Only three of these letters have provided lasting food for Ripper scholars. Two, in particular, which are written by the same individual, actually gave rise to the name “Jack the Ripper.” Before that time, the name had not been coined.

The following letter, written in red ink, gave the notorious murderer his name. It was received by Central News on September 27, 1888 and was addressed to The Boss, Central News Office.

25 Sept: 1888

Dear Boss

sent to the Central News Agency on 27

September 1888

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha.ha. The next job I do I shall clip. The lady’s ears off and send to the Police officers just for jolly wouldn’t you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance.

Good luck.

Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Don’t mind me giving the trade name

Then on the same letter, written horizontally was the following message:

wasn’t good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it. No luck yet. They Say I’m a doctor. now ha_ha

The editor treated the letter as a hoax and did not send it to the police for a couple of days. The night after the police finally received the letter, Liz Stride and Kate Eddowes were murdered. On Monday morning following the murders, the Central News Agency received another letter postmarked October 1 in the same handwriting as the September 25 letter:

cation, the ‘Saucy Jacky’ postcard of 1

October 1888

I wasn’t codding dear old Boss when I gave you the tip. youll hear about saucy Jackys work tomorrow double event this time number one squealed a bit couldn’t finish straight off. had not time to get ears for police thanks for keeping last letter back till I got to work again.

Jack the Ripper

Police circulated the letters around and placed facsimiles of them outside every police station in case someone recognized the handwriting. Nothing came of this effort except a number of crank letters.

The third important letter was sent on October 16 to George Lusk, who was the head of the Mile End Vigilance Committee. This time the letter was sent with a portion of a human kidney. Lusk was extremely upset. One of the other committee members felt sure that it was an animal organ preserved in wine, so they took the kidney to Dr. Thomas Openshaw at the London Hospital to examine. Much was published on what Dr. Openshaw allegedly said about the kidney, which he repudiated later. All that can be certain of what Dr. Openshaw really established was that it was a human adult kidney, which was preserved in spirits rather than in formalin, such as what was used in hospitals for specimens.

The letter that accompanied the kidney was not written by the author of the two earlier letters signed Jack the Ripper.

From hell

Mr Lusk

Sor

I send you half the Kidne I took from one women prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer

Signed

Catch me when

You can

Mishter Lusk

Are any of these three letters from the real murderer? Philip Sugden presents the case against the first two letters, which are signed Jack the Ripper, being genuine even though they appear to present information that only the killer might know.

First, the claim that he will send the police the victim’s ears. This was never done. While it is true that Kate Eddowes’ one ear lobe was severed, the killer had plenty of time, as evidenced by his extensive mutilations of her body, to cut off both her ears and send them to the police.

Secondly, the forecast of the double event has been promoted as a reason to accept the letters as genuine. However, the letter, whether it was posted from the Eastern District on Sunday night, September 31, or on Monday, October 1, was written when the entire Eastern region of the city was abuzz about the double murder. It was well known on the streets all of Sunday. So there was nothing forecast whatsoever.

Thirdly, the claim that Liz Stride squealed a bit is not proven. Only one of several witnesses heard a woman cry out. Most witnesses heard nothing at all that night.

Sir Charles Warren, who headed up the London police, shared this view. So do his modern day counterparts, John Douglas and Mark Olshaker, “It’s too organized, too indicative of intelligence and rationale thought, and far too ‘cutesy.’ An offender of this type would never think of his actions as ‘funny little games’ or say that his ‘knife’s so nice and sharp.'”

The Lusk letter is more difficult to assess. Dr. Openshaw indicated that the kidney belonged to a person suffering from Bright’s Disease which, according to testimony given by Dr. Brown, the police surgeon, apparently afflicted Kate Eddowes. The possibility remains that the letter is genuine and the kidney was the victim’s, but there is no way to prove it today.

The fear that swept the East End after the “Double Event” was much intensified over the level of anxiety from the Chapman murder. Predictably, for a week or so after the news got out, the streets of Whitechapel were virtually deserted after dark. Many of the prostitutes stayed off the street for as long as they could, living at various shelters and staying with family or friends.

It wasn’t just the flesh trade that suffered. Londoners were avoiding that area for any kind of commerce and shopping. Trade had fallen off sharply as people from other areas were afraid to set foot in Whitechapel.

Oddly enough, the streets were, in general, safer than they had been before since everyone was in a heightened state of alert and many more forces were patrolling the streets. There was an influx of both uniformed and plainclothes police walking the streets, particularly during the night and early morning. Plus the Mile End Vigilance Committee paid men, equipped with a police whistle and thick stick, to patrol the streets for several hours after midnight.

Since there were no women on the police force during those days, at least one policeman dressed up as a prostitute and acted as a decoy. Of course, it didn’t work and the poor man was rewarded with a lot of snide comments from the locals.

Police visited the common lodging houses, interviewing over 2,000 lodgers. Some 80,000 handbills were printed up and distributed in the neighborhood:

POLICE NOTICE

TO THE OCCUPIER

On the morning of Friday, 31st August, Saturday 8th, and Sunday, 30th September, 1888, Women were murdered in or near Whitechapel, supposed by some one residing in the immediate neighborhood. Should you know of any person to whom suspicion is attached, you are earnestly requested to communicate at once with the nearest Police Station, Metropolitan Police Office, 30th September, 1888.

Special investigative work was done for several occupations. Some 76 butchers and slaughterers were interrogated about their operations and employees. Sailors working on the Thames River boats were also questioned. With the blessing of Sir Charles Warren, a group of bloodhounds were trained and deployed to the area. However, there was always some doubt that, with the large number of people living in Whitechapel, a dog would be able to follow a single scent, particularly without an article of clothing from the killer. At the end of October, the experiment was abandoned.

Things were starting to get back to normal in Whitechapel. There had been no murder for a month and the streetwalkers again began to ply their trade in force. One such woman was a good-looking young Irish girl by the name of Mary Kelly. Police officer Walter Dew knew her by sight. “She was usually in the company of two or three of her kind, fairly neatly dressed and invariably wearing a clean white apron, but no hat.”

Mary had a lot on her mind at the beginning of November. She was several weeks behind in her rent and her lover, Joe Barnett, was unemployed. She rented a first floor room in Miller’s Court in the back of Dorset Street.

Mary was born in Limerick and had lived in Wales. When she was 21 years old, she came to London and worked in a brothel. One of her clients was sufficiently taken by her to have her accompany him to France, but the relationship did not work out and she returned a couple of weeks later. Being an attractive woman, her various lovers supported her so that she did not have to live solely by prostitution.

In 1887, she met Joe Barnett, a respectable market porter, and lived with him at various locations. Every once and awhile, they would drink up the rent money and get evicted. Finally they ended up at 13 Miller’s Court. Mary did not have many relationships and the one she had with Joe was a solid one. They lived together until they had an argument and he moved out. Since he did not have any work, she had been forced to return to prostitution to survive.

The cause of the argument was Mary’s generosity in allowing a homeless prostitute to stay with them at Miller’s Court and Mary’s returning to prostitution to earn money. But this was more of a lover’s spat than a break-up because they got together Thursday night, November 8, and he apologized for not having any money to give her.

People described her as “tall and pretty, and as fair as a lily, a very pleasant girl who seemed to be on good terms with everybody.” One of her acquaintances said she was abusive when drunk, but “one of the most decent and nicest girls you could meet when she was sober.” Another acquaintance said Mary was “5 feet 7 inches in height, and of rather stout build, with blue eyes and a very fine head of hair, which reached nearly to her waist.”

Friday, November 9, 1888, was the day for the Lord Mayor’s Show. This was a major festive event in the city. On that day, he would be sworn into office in a style befitting a prince. Like many Londoners, Mary was planning on seeing this spectacle.

John McCarthy sent his assistant, Thomas Bowyer, to see if he could collect any rent from Mary that Friday morning. When his knock went unanswered, he reached inside the broken window and pulled aside the curtain. He wasn’t quite sure what he saw, but it caused him to run back to McCarthy. When McCarthy looked through the window, he was so horrified that he sent Bowyer for a constable.

Miller’s Court

The constable was talking with police officer Walter Dew and they went immediately to 13 Miller’s Court. They did not force the door, but pushed away a coat that served as a curtain over the broken window. The constable told Dew not to look inside, but he did anyway. “When my eyes had become accustomed to the dim light I saw a sight which I shall never forget to my dying day.”

Soon Dr. George Bagster Phillips, the police surgeon, and Inspector Abberline were there. They opened the door to a small, cluttered room with almost no furniture. Mary’s body, unbelievably mutilated, lay sprawled on the bed. The cause of death was the severance of the carotid artery in the throat. The horrendous mutilation of this last and most hideous Ripper murder was done after her death.

Dr. Thomas Bond, another veteran police surgeon, had been brought into the case specifically to determine the extent of medical knowledge the killer had. Dr. Phillips’ examination report did not survive, but Dr. Bond’s did:

The body was lying naked in the middle of the bed, the shoulders flat, but the axis of the body inclined to the left side of the bed…The whole of the surface of the abdomen & thighs was removed & the abdominal cavity emptied of its viscera. The breasts were cut off, the arms mutilated by several jagged wounds & the face hacked beyond recognition of the features & the tissues of the neck were severed all round down to the bone. The viscera were found in various parts: the uterus & kidney with one breast under the head, the other breast by the right foot, the liver between the feet, the intestines by the right side & the spleen by the left side. The flaps removed from the abdomen & thighs were on a table.

The ferocity of this murder astounded the veteran police surgeons. Her throat had been slashed with such force that the tissues had been cut all the way down to the spinal column. Dr. Bond went on to describe the ghastly destruction of her body:

Her face was gashed in all directions, the nose, cheeks, eyebrows & ears being partly removed. The lips were blanched & cut by several incisions running obliquely down to the chin. There were also numerous cuts extending irregularly across all of the features.

The skin & tissues of the abdomen from the costal arch to the pubes were removed in three large flaps. The right thigh was denuded in front to the bone, the flap of skin including the external organs of generation & part of the right buttock. The left thigh was stripped of skin, fascia & muscles as far as the knee.

Dr. Bond went on in his report for several paragraphs, cataloging the wounds and stripping of the skin. As they tried to reconstruct her torn body, they realized that the heart had been cut out and taken away.

There seemed to be agreement that the same monster that killed the other four women murdered Mary Kelly. All of the women were murdered with “a very sharp, strong knife about an inch in width and at least six inches long.”

Dr. Bond fixed the time of the murder as between one or two o’clock in the morning. However, given the length of time between her death and the time she was examined by Dr. Phillips, the time of death was approximate.

To the question that Dr. Bond was asked to address the medical skill of Jack the Ripper – he replied: “In each case the mutilation was inflicted by a person who had no scientific nor anatomical knowledge. In my opinion he does not even possess the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer or any person accustomed to cut up dead animals.” It is possible that Dr. Bond could not imagine that a doctor would be capable of such atrocities, because his position is very different than other physicians who examined the victims.

The murder of Mary Kelly created panic in the streets of Whitechapel, which were again abandoned at night to the police patrols. Sporadic episodes of mob violence broke out when for various reasons, an individual cast suspicion on himself by something he did or said, usually under the influence of alcohol.

Police activity was frantic. Every lead was tracked down, every suspect interrogated thoroughly. The results were disappointing and the police were heavily criticized. Queen Victoria was furious. “This new most ghastly murder,” she told the Prime Minister, “shows the absolute necessity for some very decided action. All these courts must be lit, and our detectives improved. They are not what they should be.”

The Times was a bit more understanding of the difficulties the police faced: “The murders, so cunningly continued, are carried out with a completeness which altogether baffles investigators. Not a trace is left of the murderer, and there is no purpose in the crime to afford the slightest clue…All that the police can hope is that some accidental circumstance will lead to a trace which may be followed to a successful conclusion.”

There was disagreement on the estimated time of Mary’s death. Dr. Bond believed that she had died between 1 and 2 a.m. Friday morning. Dr. Phillips thought that death occurred much later, somewhere between 5 and 6 a.m. Not having a clearer idea about time of death complicated the eyewitness testimony regarding who was with Mary or seen in Miller’s Court during Friday morning.

murder of Mary Kelly

The most important eyewitness was George Hutchinson, a laborer who knew Mary Kelly. He met her about 2 a.m. Friday morning and she asked him for some money. He told her he had nothing to spare and she walked away, but soon stopped to talk to another man. If his testimony is correct, he probably saw Jack the Ripper:

He then placed his right hand around her shoulders. He also had a kind of a small parcel in his left hand with a kind of strap round it. I stood against the lamp of the Queen’s Head Public House and watched him. They both then came past me and the man hung down his head with his hat over his eyes. I stooped down and looked him in the face. He looked at me stern. They both went into Dorset Street. I followed them. They both stood at the corner of the court for about 3 minutes. He said something to her. She said alright my dear come along you will be comfortable. He then placed his arm on her shoulder and gave her a kiss. She said she had lost her handkerchief. He then pulled his handkerchief a red one out and gave it to her. They both then went up the court together. I then went to the court to see if I could see them but could not. I stood there for about three quarters of an hour to see if they came out. They did not so I went away.

Description: age about 34 or 35, height 5 ft. 6, complexion pale, dark eyes and eye lashes, slight moustache curled up each end and hair dark, very surly looking; dress, long dark coat, collar and cuffs trimmed astrakhan and a dark jacket under, light waistcoat, dark trousers, dark felt hat turned down in the middle, button boots and gaiters with white buttons, black tie with horse shoe pin, respectable appearance, walked very sharp, Jewish appearance. Can be identified.

He further elaborated on this description later:

His watch chain had a big seal, with a red stone, hanging from it…He had no side whiskers, and his chin was clean shaven…I believe that he lives in the neighborhood, and I fancied that I saw him in Petticoat Lane on Sunday morning, but I was not certain.

Several people had seen Mary on the night she died. Mary Ann Cox, another prostitute who lived in Miller’s Court, saw Mary with a man going into Miller’s Court at 11:45 p.m. Mary was very drunk and had difficulty talking. Mrs. Cox described Mary’s client as “about 36 years old, about 5 ft 6 in. high, complexion fresh and I believe he had blotches on his face, small side whiskers, and a thick carrotty moustache, dressed in shabby dark clothes, dark overcoat and black felt hat.”

At 8 p.m. on Wednesday, November 7, laundress Sarah Lewis was walking with a girlfriend when a man about forty years of age, who was fairly short, pale-faced, with a black moustache, wanted either one of the two women to follow him. He wore a short black coat and carried a black bag about one foot long. They refused, but he persisted, and the women ran away. At 2:30 a.m. Friday morning, just around the time that Mary Kelly was murdered, Sarah was coming to stay with friends at 2 Miller’s Court when she saw the same man, but eluded him this time. Shaken by this second sighting, she rushed to her friend’s house. Just before 4 a.m. she heard a woman shriek “Murder!” Another woman also heard the scream, but shrieks like that were apparently common in bawdy Whitechapel.

Abberline

Inspector Abberline clearly believed Hutchinson’s detailed account, but had to wonder about Hutchinson’s motivation for following Mary and her client. He said he had known her for several years and had given her money more than once. Perhaps he was fond of Mary or just worried about her with this particular client. There had to be some reason that he would take such an interest and even follow the two of them to Miller’s Court. Abberline instructed a couple of policemen to walk around with Hutchinson in the hopes that they would spot Mary’s client. One cannot help wondering if Hutchinson did not make up this story to throw suspicion off of himself. However, for some reason, the police did not pursue him as a suspect and disseminated the description that he gave to all of the police stations.

As winter set in, the frantic police activity began to slow. All suspects had been interrogated and leads came to a dead end. It appeared that Jack the Ripper had left the scene for good. However, there were two murders that were similar in nature that should be mentioned.

The first was Alice McKenzie, who was found dead in July of 1889. She too had died from the slashing of her carotid artery. If this was another victim of Jack the Ripper, the wounds to her throat and abdomen were different than the other murders. Drs. Bond and Phillips disagreed as to whether it was Jack or not.

In February of 1891, a pretty prostitute named Frances Coles was found with her throat cut. Dr. Phillips did not believe that Jack the Ripper was responsible and suspicion fell upon a man who had a quarrel with her.

At any rate, the Jack the Ripper file was closed in 1892, the same year in which Inspector Abberline retired. The Ripper murders were over, but the legend lived on.

Before looking at specific suspects, let’s summarize what is known about Jack the Ripper from forensic surgeons and possible eyewitnesses.

From the testimony of the various eyewitnesses which police took most seriously, certain probabilities emerge about the killer. One must keep in mind the word probable since eyewitness accounts, particularly under conditions of dim lighting, are notoriously inaccurate in certain details even when offered by honest competent eyewitnesses.

The following is a list of probabilities about the Ripper:

-

A white male

-

Average or below average height

-

Between 20 and 40 years of age in 1888

-

Did not dress as laborer or indigent poor

-

Had lodgings in the East End

-

Did have medical expertise, despite 1-2 opinions to contrary

-

May have been foreigner

-

Right-handed

-

Had a regular job since the murders all occurred on weekends

-

Was single so that he could roam streets at all hours

Developing persuasive cases about Jack the Ripper suspects has become a profitable cottage industry for at least one hundred years. Many of these books promote one suspect or another as the “real Jack the Ripper.” Usually the author conveniently compiles “evidence” that fits his pet theory and denigrates or ignores facts that don’t support that theory. Given the vast number of suspects and books promoting particular suspects, a reader must be very skeptical of any new “final solutions” to the crimes.

Despite the thousands of hours of work on this case, there is not yet one suspect for which a strong unimpeachable case can be made. One remains hopeful that someday a suspect will emerge with better credentials than the ones currently promoted.

With those caveats in mind, certain suspects have garnered more interest than others and will be listed in this chapter. A few major suspects will be dealt with briefly in subsequent chapters.

Sir Melville Macnaghten succeeded Sir Charles Warren as the Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in June of 1889, after the Ripper murders had officially ended. However, the investigation was ongoing and Macnaghten had complete access to police files. His final report addresses his thoughts on why the murders came to an end with the monstrous destruction of Mary Kelly, and with the identity of the three key suspects he believed could be Jack the Ripper:

A much more rational theory is that the murderer’s brain gave way altogether after his awful glut in Miller’s Court, and that he immediately committed suicide, or, as a possible alternative, was found to be so hopelessly mad by his relations, that he was by them confined in some asylum.

No one ever saw the Whitechapel murderer: many homicidal maniacs were suspected, but no shadow of proof could be thrown on any one. I may mention the cases of 3 men, any one of whom would have been…(likely) to have committed this series of murders:

(1) A Mr. M. J. Druitt, said to be a doctor & of good family, who disappeared at the time of the Miller’s Court murder, & whose body was found in the Thames on 31st December — or about seven weeks after that murder. He was sexually insane and from private information I have little doubt but that his own family believed him to have been the murderer.

(2) Kosminski, a Polish Jew, & resident in Whitechapel. This man became insane owing to many years’ indulgence in solitary vices. He had a great hatred of women, specially of the prostitute class, & had strong homicidal tendencies; he was removed to a lunatic asylum about March 1889. There were many circumstances connected with this man which made him a strong ‘suspect.’

(3) Michael Ostrog, a Russian doctor, and a convict, who was subsequently detained in a lunatic asylum as a homicidal maniac. This man’s antecedents were of the worst possible type, and his whereabouts at the time of the murders could never be ascertained.

Each one of these three major suspects that Macnaghten identified is addressed in subsequent chapters, as are several other major theories. A few of the many suspects held up by authors over the years is addressed in the chapter entitled “Other Suspects.”

The most important detective in the murder series was Chief Inspector Frederick George Abberline. He did not agree with Sir Melville Macnaghten on the viability of the three suspects listed above. In 1903, he said: “You can state most emphatically that Scotland Yard is really no wiser on the subject than it was fifteen years ago.”

However, Chief Inspector Abberline did eventually have a favorite suspect of his own, one George Chapman, who was hanged in 1903 for poisoning his wife.

The theory that a royal conspiracy was behind the murders is a very popular one. Not only is it the premise of the 2001 movie From Hell with Johnny Depp and Heather Graham, it has spawned made-for-TV movies and documentaries and books.

Duke of Clarence

This most appealing theory unfolds like this: Prince Albert Victor, known popularly as Eddy, was the grandson of Queen Victoria and in direct line to the throne of England. His father later became King Edward VII. Had Eddy outlived his father, he would have become King of England.

Eddy frequently went slumming in the Whitechapel area. He met and had an affair with a shop girl named Annie Crook, who he kept in an apartment there. Annie became pregnant with his child and, according to one version of the story, married Eddy secretly in a Roman Catholic wedding. Other versions have the child being born out of wedlock.

Marrying or impregnating a Catholic girl of low social standing was a definite no-no for a future king, and wind of this scandal got back to Grandma, who insisted on a resolution to the problem. The prime minister delegated this task to Queen Victoria’s physician, Sir William Gull.

Dr. Gull had Annie taken away to a hospital where he savaged her memory and intellect, leaving her institutionalized for the rest of her life. Mary Kelly was caring for Annie’s royal daughter, named Alice Margaret, when Annie was kidnapped. Mary Kelly, along with her friends, Polly Nichols, Annie Chapman, and Elizabeth Stride, all knew about the relationship between Annie Crook and the prince, as well as their infant daughter. But they couldn’t keep their mouths shut and thus became a major liability to the Crown.

Again Dr. Gull was asked for his help, this time in permanently silencing Mary Kelly and her friends. To explain the sudden demise of these troublesome whores, Dr. Gull cleverly created the persona of Jack the Ripper, a frenzied lust murderer with some degree of medical expertise.

Gull’s trusty coachman locates each of the friends of Mary Kelly and persuades them individually to get into the coach. Dr. Gull then murders each woman, mutilates her in increasingly savage ways and leaves her dead on the street. Mary and her dwindling group of friends believe that a vicious gang that has threatened them in the past is responsible for the murders. Dr. Gull saves Mary for last and subjects her to ghoulish butchery.

One variation of the theory has Dr. Gull, whose intellect has been impaired by a stroke, becoming a kind of Masonic ritual executioner. Not only does Gull go to great lengths to create the belief that a sex-crazed doctor has perpetrated the series of murders, he also weaves into that creation some obscure ancient Masonic lore. Gull’s Masonic group, which is the virtual Who’s Who of the London upper class, includes top police officials like Sir Robert Anderson, who help Gull in his efforts to protect the throne.

Everybody loves a conspiracy theory and no doubt this one will endure for a long time despite the fact that there is no evidence to support it and quite a lot of reason to doubt that there is any truth to it at all.

There did exist a woman named Annie Crook who worked in a shop in Cleveland Street, and she had an illegitimate daughter named Alice Margaret. But there is nothing to connect her to a relationship with Eddy, whose sexual preferences were rumored to be men rather than women. Homosexuality was against the law in Victorian England and a man of Eddy’s social standing would have to be very discreet if he were homosexually inclined.

Cleveland Street was the home of a brothel that catered to wealthy homosexuals. The brothel was raided, giving rise to strong rumors that Eddy was one of the patrons there, but there is no existing evidence of his presence there at the time of the raid. Also, there is nothing to connect Annie Crook to Mary Kelly, or to connect Mary Kelly to any of the other victims of Jack the Ripper. There is no evidence to suggest that they even knew each other at all and it is most unlikely that they were a tightly knit group of friends, or it would have been discovered in the interviews that police had with the families and friends of each victim.

The victims of Jack the Ripper were murdered where they were found, not in a coach or at some other location. Also, from witnesses in the crime scene areas, it is very unlikely that more than one man carried out the crimes.

Regarding Dr. Gull’s ability to be Jack the Ripper, Donald Rumbelow in The Complete Jack the Ripper points out: